A Review of Nanotechnology in Food, Smart Packaging and Potential Public Health Impact

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Smart Packaging (Types, Applications, Trends Etc.) and Consumers’ Acceptance

2.1. Smart Packaging (Types, Applications, Trends Etc.)

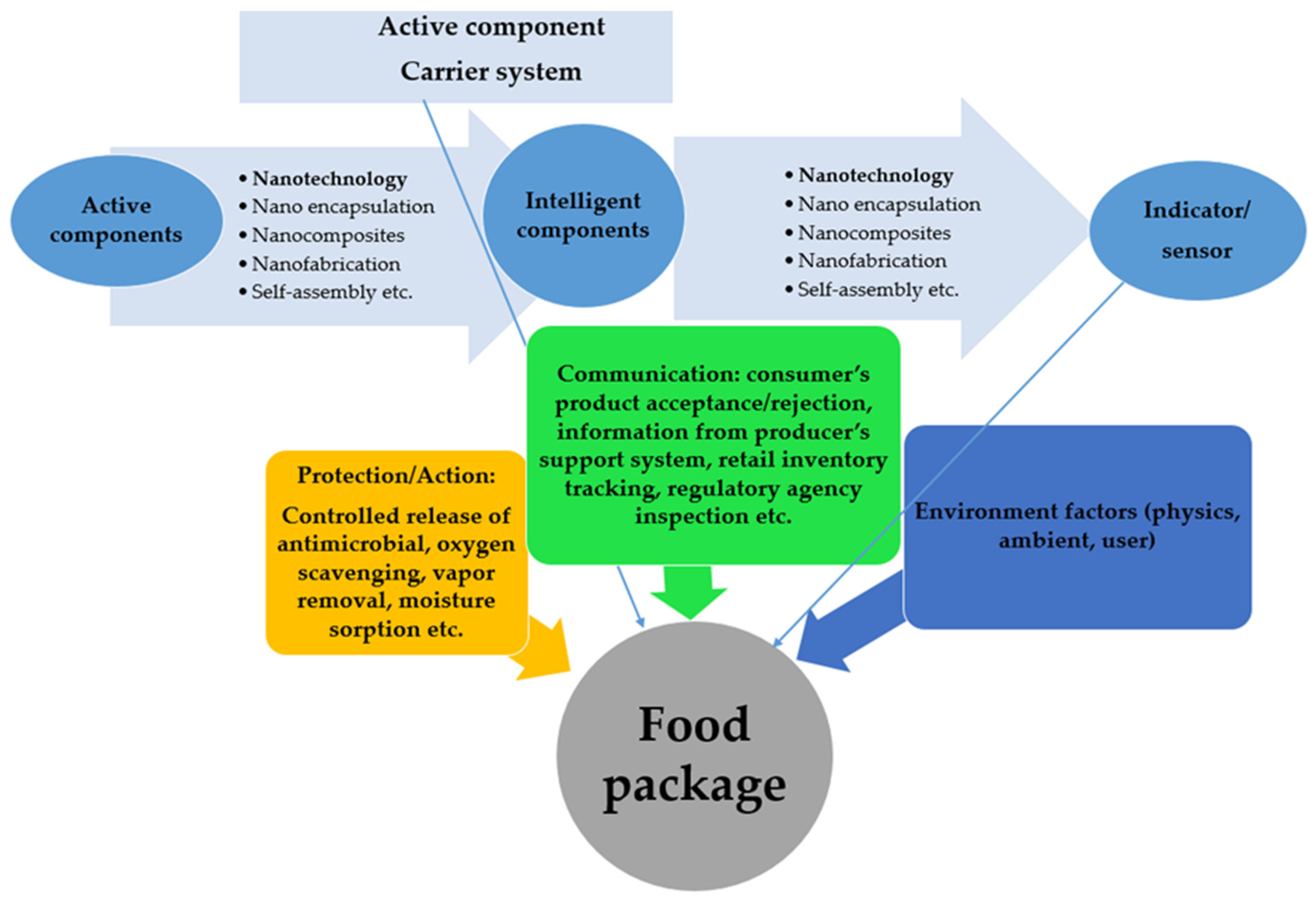

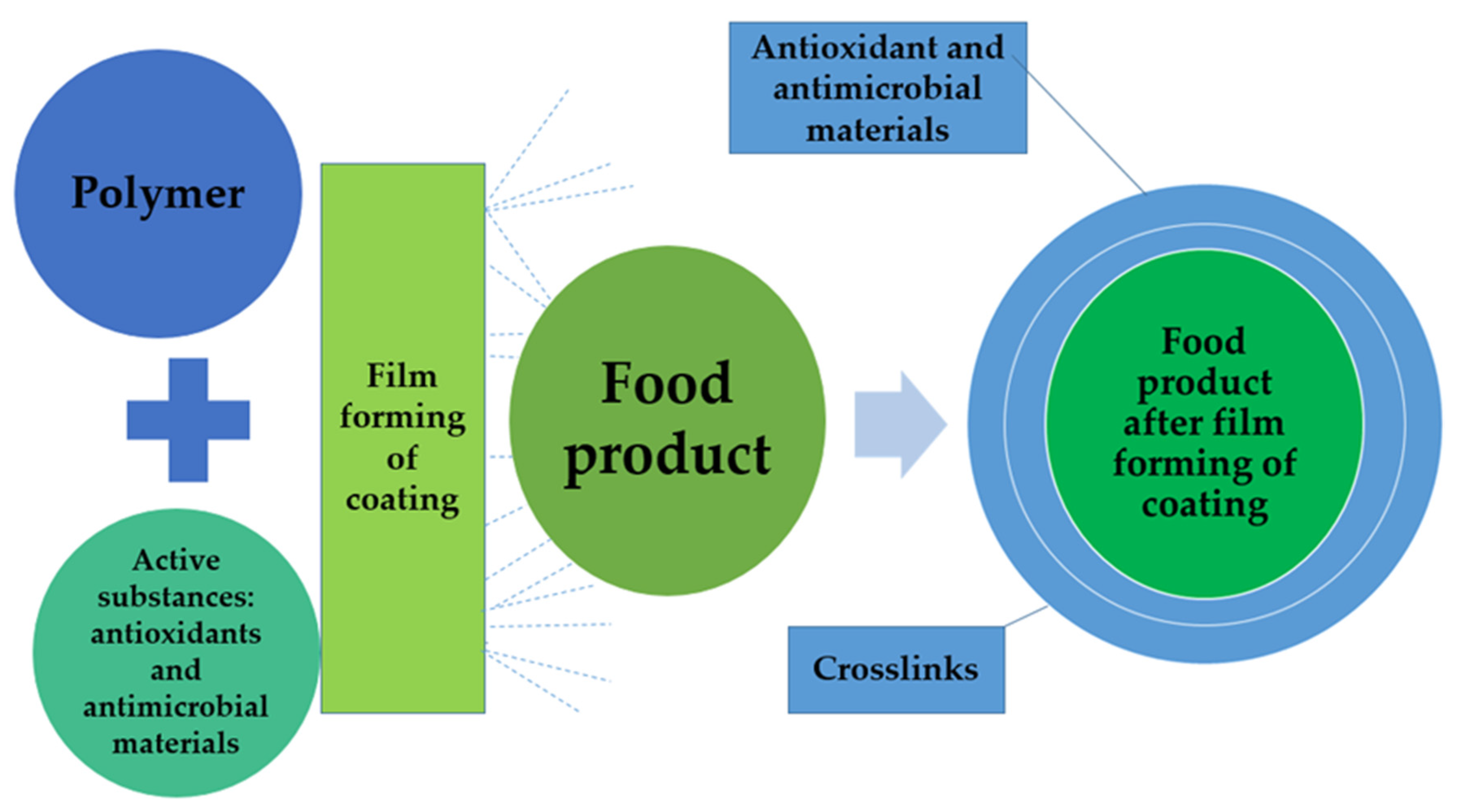

- Active Packaging: Interacts with the contents to extend shelf life or maintain quality (e.g., oxygen scavengers, antimicrobial layers). Unlike conventional packaging, which acts as a passive barrier, active packaging includes components that deliberately absorb or release substances within the package [11]. Oxygen scavengers remove residual oxygen to prevent oxidation and spoilage, while moisture regulators control humidity levels to prevent microbial growth or product degradation [12]. Antimicrobial films/layers inhibit the growth of bacteria or fungi on the product surface. Ethylene absorbers, commonly used in fruit and vegetable packaging, slow down ripening and help maintain freshness [9].

- Intelligent Packaging: Provides real-time data about the product condition. Intelligent packaging refers to packaging systems that monitor the condition of a product, provide real-time information, and improve traceability and safety throughout the supply chain [13]. It does not change the product or packaging environment (unlike active pack-aging), but it communicates useful data to manufacturers, retailers, and consumers [14]. Some examples of Intelligent packaging technologies are the Time–Temperature Indicators (TTIs), these sensors change color to show whether a product has been exposed to temperatures outside the recommended range [15]. Commonly used for perishable foods, vaccines, and pharmaceuticals. Finally, other examples are Quick Response (QR) Codes that are scan able codes that give consumers access to detailed product information such as origin, nutritional facts, instructions [13], or authenticity verification and Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) Tags, wireless tags that enable automatic identification and tracking of products, useful for inventory control, supply chain logistics, and ensuring product authenticity, e.g., time-temperature indicators, Quick Response (QR) codes, Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) tags [16].

2.1.1. Tags/Barcodes (1-D Barcode, 2-D Barcode, QR Code, RFID Tags)

2.1.2. Indicators (Microbial Growth, Gas Leakage/Concentration Indicators and Freshness Indicators and Time Temperature Indicators)

2.1.3. Sensors (Gas Sensors, Fluorescence Based Oxygen Sensors, Bio Sensors)

2.2. Consumers’ Acceptance

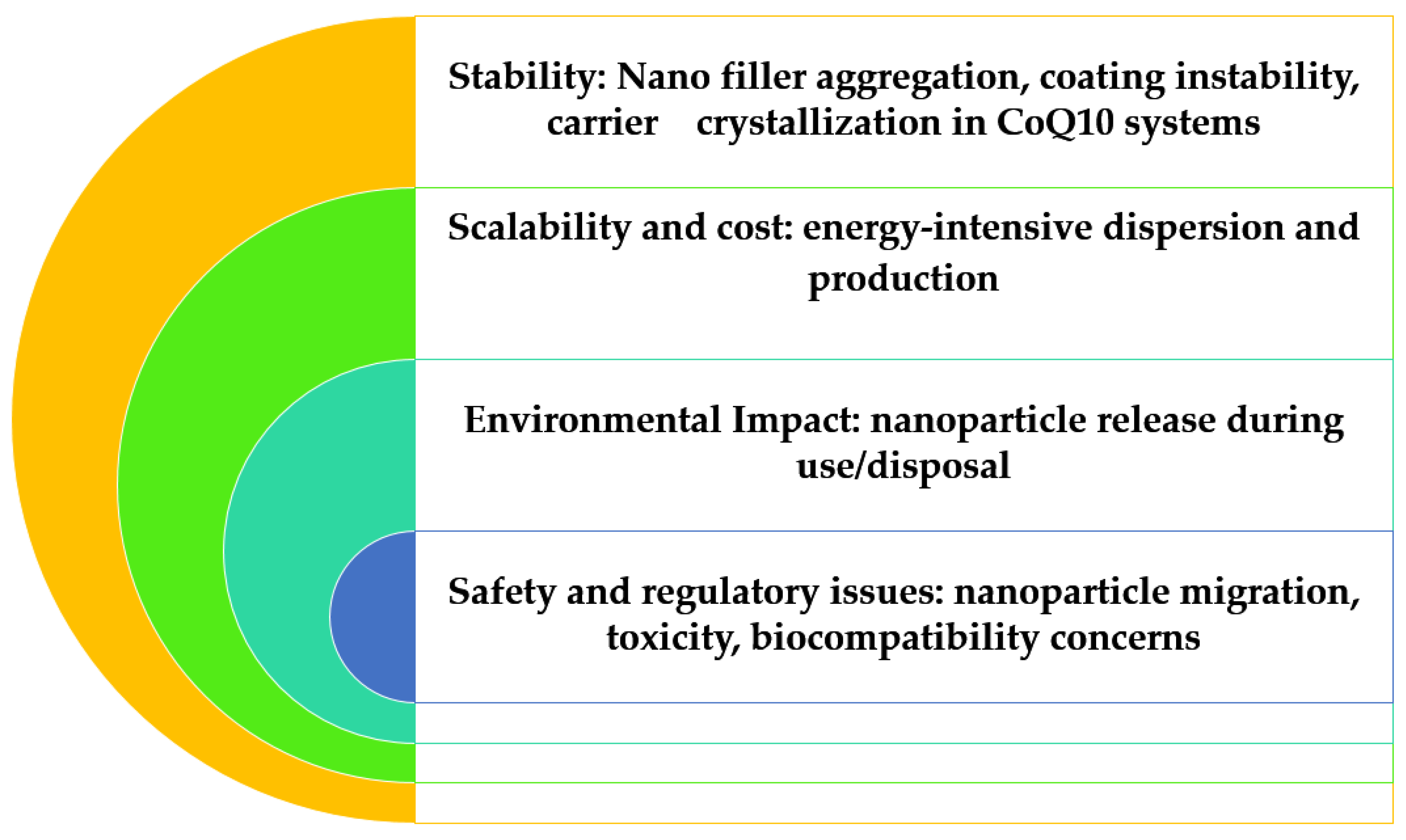

3. Potential Toxicity of Nanomaterials, Consumer Acceptance and Regulatory Issues

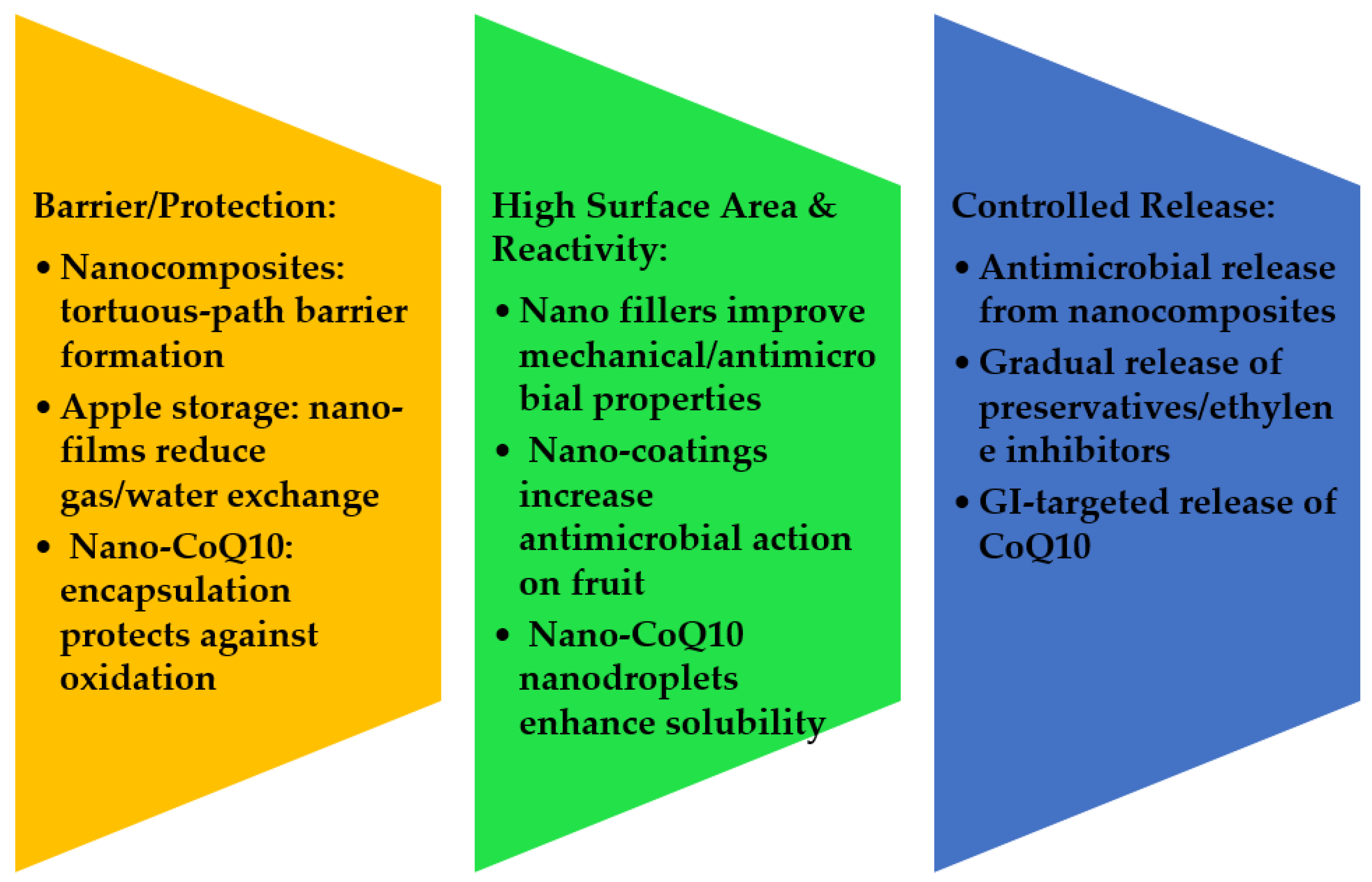

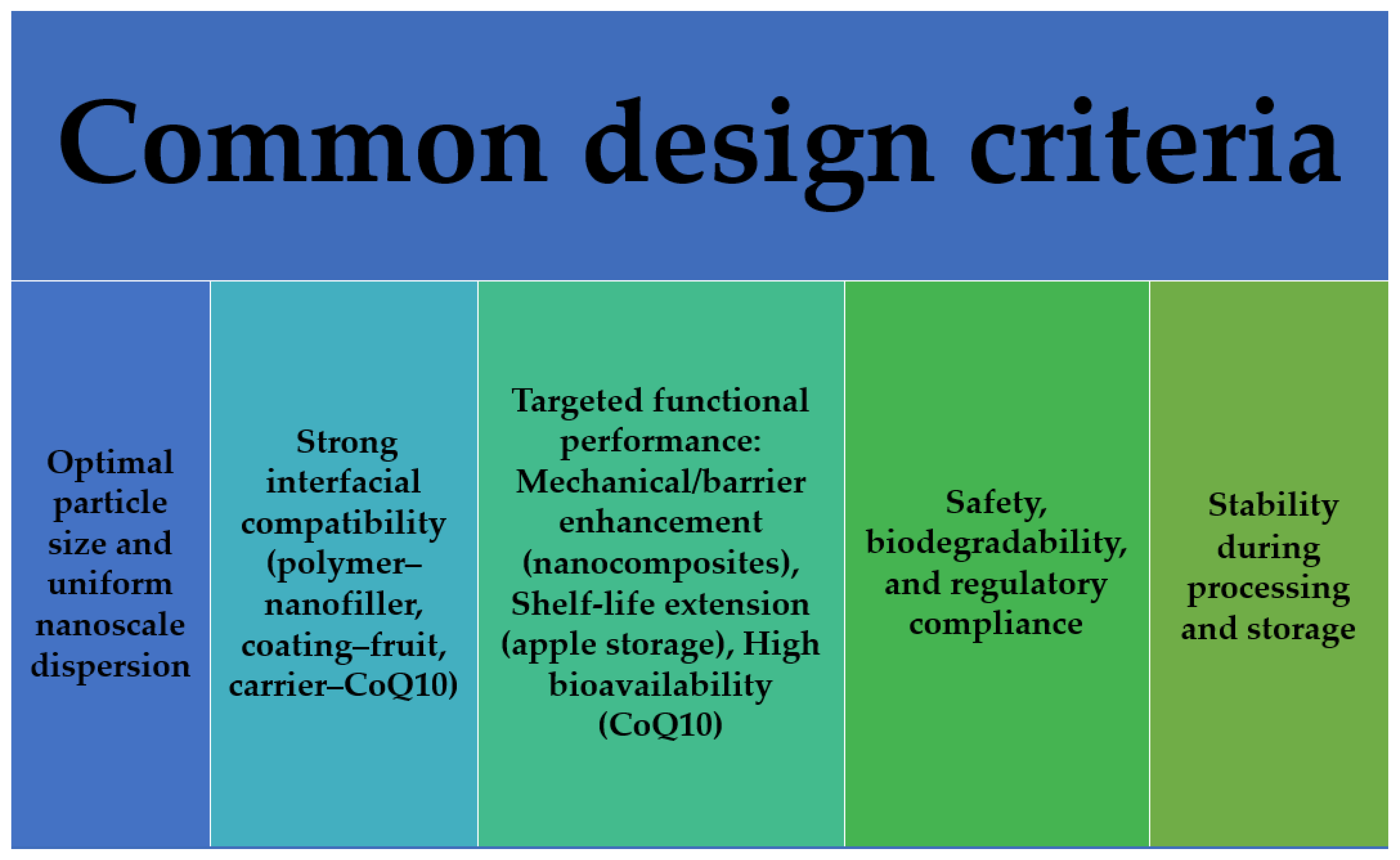

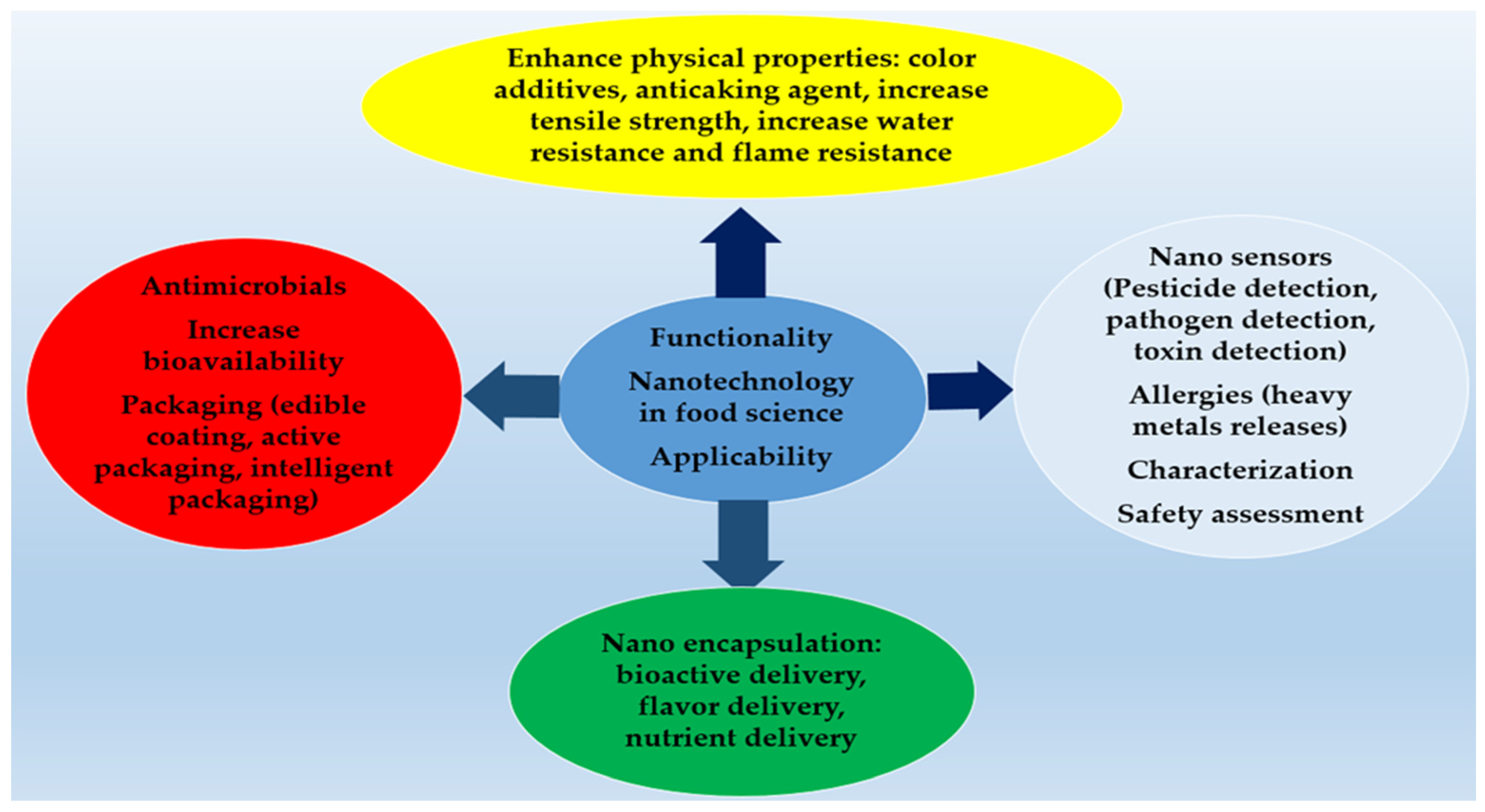

3.1. Nanotechnology, Smart Packaging and Antimicrobial Properties

3.2. Nanotechnology and Increasing Bio Acceptability

3.3. Nanotechnology, Food Packaging and Possible Public Health Impact

| Authors/Year | Nanomaterial/Type | Study Type | Key Mechanistic Findings | Relevance to Food Packaging/Consumer Health | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stuparu-Cretu et al., 2023 | Metal oxide NPs (TiO2, ZnO, Ag) | Review | ROS generation, oxidative stress, inflammation, genotoxicity | Highlights risks of NP migration from packaging; underscores need for safety assessment | [105] |

| Gupta et al., 2024 | Various NPs in packaging | Review | Oxidative stress, DNA damage, cellular dysfunction | Summarizes evidence gaps in chronic exposure and regulatory assessment | [106] |

| Angelescu et al., 2024 | Silver NPs | Review | Cytotoxicity, ROS, gut microbiota alterations | Directly relates to nanoenabled packaging and dietary exposure | [107] |

| Du et al., 2025 | Silver SiO2 NPs | In vivo (mice) | Altered gut microbiota, disrupted serotonin metabolism | Shows systemic and metabolic effects. | [108] |

| Han et al., 2025 | Silver NPs | In vivo (mice) | Liver accumulation, fibrosis, gut-liver axis perturbation | Demonstrates long-term organ-specific toxicity relevant to chronic exposure | [109] |

| Wang et al., 2023 | Silver NPs | In vivo (mice) | Neurotoxicity, oxidative stress, NF-κB activation, gut–brain axis disruption | Suggests chronic ingestion could have central nervous system implications | [110] |

| Medina-Reyes et al., 2020 | TiO2, ZnO, SiO2, Ag | Review | ROS, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation | Illustrates general toxicological mechanisms of foodborne NPs | [111] |

| Herrera-Rodríguez et al., 2023 | TiO2, ZnO | In vivo (rats) | Cardiac toxicity, oxidative stress | Evidence of systemic effects from dietary NP exposure | [112] |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Müller, P.; Schmid, M. Intelligent packaging in the food sector: A brief overview. Foods 2019, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, I.; Nayik, G.A.; Dar, S.M.; Nanda, V. Novel food packaging technologies: Innovations and future prospective. JSSAS 2018, 17, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, T.P.; Gillespie, J.; Cama-Moncunill, X.; Ward, S.; Condell, J.; Ramanathan, R.; Murphy, F. A Systematic Review of Real-Time Monitoring Technologies and Its Potential Application to Reduce Food Loss and Waste: Key Elements of Food Supply Chains and IoT Technologies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, H.; Su, H.-M.; Imani, S.M.; Alkhaldi, K.M.; Filipe, C.D.; Didar, T.F. Intelligent food packaging: A review of smart sensing technologies for monitoring food quality. ACS Sens. 2019, 4, 808–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, N.; Jain, U.; Soni, S.U. Sensors for food quality monitoring. In Nanoscience for Sustainable Agriculture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 601–626. [Google Scholar]

- Wohner, B.; Pauer, E.; Heinrich, V.; Tacker, M. Packaging-related food losses and waste: An overview of drivers and issues. Sustainability 2019, 11, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahyaoglu, L.N. Intelligent Packaging System: A Promising Approach to Reduce Food Waste. Curr. Food Sci. Technol. Rep. 2024, 2, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeson, K.; Mouriya, G.K.; Bhubalan, K.; Razifah, M.R.; Jasmine, R.; Sowmiya, S.; Amirul, A.-A.A.; Vigneswari, S.; Ramakrishna, S. Smart packaging—A pragmatic solution to approach sustainable food waste management. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 36, 101044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouhoub, A.; Guendouz, A.; El Alaoui-Talibi, Z.; Ibnsouda Koraichi, S. El Modafar Optimization of Chitosan-Based Film Performance by the Incorporation of Cinnamomum Zeylanicum Essential Oil. Food Biophys. 2025, 20, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.U.; Rathi, P.; Beshai, H.; Sarabha, G.K.; Deen, M.J. Fruit quality monitoring with smart packaging. Sensors 2021, 21, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awulachew, M.T. A review of food packaging materials and active packaging system. Int. J. Health Policy Plann 2022, 1, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ogwu, M.C.; Ogunsola, O.A. Physicochemical methods of food preservation to ensure food safety and quality. In Food Safety and Quality in the Global South; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 263–298. [Google Scholar]

- Rotsios, K.; Konstantoglou, A.; Folinas, D.; Fotiadis, T.; Hatzithomas, L.; Boutsouki, C. Evaluating the use of QR codes on food products. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, K. Time–Temperature Indicators (TTIs) for Monitoring Food Quality. In SFPS: Innovations and Technology Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 281–304. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadian, E.; Alizadeh-Sani, M.; Jafari, S.M. Smart monitoring of gas/temperature changes within food packaging based on natural colorants. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 2885–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drago, E.; Campardelli, R.; Pettinato, M.; Perego, P. Innovations in smart packaging concepts for food: An extensive review. Foods 2020, 9, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Dutt, R.; Gaikwad, K.K. Packaging 4.0: Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications in the Food Packaging Industry. Curr. Food Sci. Technol. Rep. 2025, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi-Firoozjah, R.; Salim, S.A.; Hasanvand, S.; Assadpour, E.; Azizi-Lalabadi, M.; Prieto, M.A.; Jafari, S.M. Application of smart packaging for seafood: A comprehensive review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 1438–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, A.; Gaikwad, K.K. Data carriers for real-time tracking and monitoring in smart, intelligent packaging applications: A technological review. Next Mater. 2025, 8, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I. An overview of smart packaging technologies for monitoring safety and quality of meat and meat products. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2018, 31, 449–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, J. Future of food packaging: Intelligent packaging. In Nanotechnology in Intelligent Food Packaging; Annu, Bhattacharya, T., Ahmed, S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 383–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, M.; Bichescu, C.I.; Crețu, C.-M.; Dragomir, M.; Ivan, A.S.; Podaru, G.M.; Stoica, D.; Stuparu-Crețu, M. Review of Bio-Based Biodegradable Polymers: Smart Solutions for Sustainable Food Packaging. Foods 2024, 13, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandian, A.T.; Chaturvedi, S.; Chakraborty, S. Applications of enzymatic time–temperature indicator (TTI) devices in quality monitoring and shelf-life estimation of food products during storage. Food Meas. 2021, 15, 1523–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, G. Recent trends in active, smart, and intelligent packaging for food products. In Food Packaging and Preservation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 343–374. [Google Scholar]

- Mani, R.; Kumar, J.V.; Murugesan, B.; Alaguthevar, R.; Rhim, J.W. Smart Sensors in Food Packaging: Sensor Technology for Real-Time Food Safety and Quality Monitoring. J. Food Process Eng. 2025, 48, e70120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrucka, R.; Przekop, R. New perspectives in active and intelligent food packaging. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e14194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Yu, Z.; Ye, C.; Pan, L.; Song, Y. Principle, development and application of time–temperature indicators for packaging. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2023, 36, 833–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.; Maruthupandy, M.; Lee, K.; Kim, D.; Seo, J. Freshness indicator for monitoring changes in quality of packaged kimchi during storage. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 25, 100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshai, H.; Sarabha, G.K.; Rathi, P.; Alam, A.U.; Deen, M.J. Freshness monitoring of packaged vegetables. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zaitoon, A.; Lim, L.T. A review on colorimetric indicators for monitoring product freshness in intelligent food packaging: Indicator dyes, preparation methods, and applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 2489–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishore, A.; Aravind S, M.; Kumar, P.; Singh, A.; Kumari, K.; Kumar, N. Innovative packaging strategies for freshness and safety of food products: A review. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2024, 37, 399–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danchuk, A.I.; Komova, N.S.; Mobarez, S.N.; Doronin, S.Y.; Burmistrova, N.A.; Markin, A.V.; Duerkop, A. Optical sensors for determination of biogenic amines in food. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 4023–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Huang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Luo, Y.; Huang, K.; Cheng, N. Recent advances in personal glucose meter-based biosensors for food safety hazard detection. Foods 2023, 12, 3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.F.; de Sousa Picciani, P.H.; Calado, V.; Tonon, R.V. Electrical gas sensors for meat freshness assessment and quality monitoring: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, W.; Lim, S. A review on gas indicators and sensors for smart food packaging. Foods 2024, 13, 3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaalan, N.M.; Ahmed, F.; Saber, O.; Kumar, S. Gases in food production and monitoring: Recent advances in target chemiresistive gas sensors. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patric, D.R.; Fardo, S.W. Level Determining Systems. In Industrial Process Control Systems, 2nd ed.; River Publishers: Gistrup, Denmark, 2021; pp. 185–220. [Google Scholar]

- Osmólska, E.; Stoma, M.; Starek-Wójcicka, A. Application of biosensors, sensors, and tags in intelligent packaging used for food products—A review. Sensors 2022, 22, 9956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.J.; Lee, S.M.; Oh, M.H.; Huh, Y.S.; Jang, H.W. Food quality assessment using chemoresistive gas sensors: Achievements and future perspectives. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, R.K. Non-dispersive infrared gas sensing technology: A review. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 22, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struzik, M.; Garbayo, I.; Pfenninger, R.; Rupp, J.L. A simple and fast electrochemical CO2 sensor based on Li7La3Zr2O12 for environmental monitoring. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1804098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhan, A.; Muthukumarappan, K.; Wei, L. Biosensors and biopolymer-based nanocomposites for smart food packaging: Challenges and opportunities. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2021, 30, 100745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Solano, M. Nanotechnology Principles for the Detection of Foodborne Bacterial Pathogens and Toxins. In Nanobiotechnology for Sustainable Food Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 241–278. [Google Scholar]

- Young, E.; Mirosa, M.; Bremer, P. A systematic review of consumer perceptions of smart packaging technologies for food. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Brahma, S.; Mackay, J.; Cao, C.; Aliakbarian, B. The role of smart packaging system in food supply chain. J. Forensic Sci. 2020, 85, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodero, A.; Escher, A.; Bertucci, S.; Castellano, M.; Lova, P. Intelligent packaging for real-time monitoring of food-quality: Current and future developments. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydzkowski, T.; Wróblewska-Krepsztul, J.; Thakur, V.K.; Królikowski, T. Current trends of intelligent, smart packagings in new medical applications. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 207, 1271–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostan, M. A Comparative Study on QR Code and Bar Code Detection Techniques in Modern Systems. Int. J. Synerg. Eng. Technol. 2025, 6, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, C.M.; Alves, J.; Gaspar, P.D.; Lima, T.M.; Silva, P.D. Innovative processes in smart packaging. A systematic review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 986–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakoudis, E.D.; Pechlivanidou, G.G.; Tipi, N.S. Sustainable Packaging Design: Packaging Optimization and Material Reduction for Environmental Protection and Economic Benefits to Industry and Society. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Jakku, E. Australian consumers’ preferences for food attributes: A latent profile analysis. Foods 2020, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, M.; Majid, I.; Nanda, V. Smart Packaging for Managing and Monitoring Shelf Life and Food Safety. In Shelf Life and Food Safety; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 285–306. [Google Scholar]

- Tiekstra, S.; Dopico-Parada, A.; Koivula, H.; Lahti, J.; Buntinx, M. Holistic approach to a successful market implementation of active and intelligent food packaging. Foods 2021, 10, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yang, L.; Shang, M.; Zhong, Y. Research progress of packaging indicating materials for real-time monitoring of food quality. Mater. Express 2019, 9, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, W.; Ye, S.; Batista, L. Packaging design for the circular economy: A systematic review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 32, 817–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, M.; Malagas, K.; Nomikos, S.; Papapostolou, A.; Vlassas, G. An Overview of the Impact of the Food Sector “Intelligent Packaging” and “Smart Packaging”. Eur. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2023, 15, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreira-Pinto, R.; Carneiro, R.; Miranda, M.; Guedes, R.M. Polymer-matrix composites: Characterising the impact of environmental factors on their lifetime. Materials 2023, 16, 3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, W.C.; Yu, Y.L.; Liang, Y.J.; Wang, C.Y.; Lin, Y.C.; Chang, H.C.; Lin, F.H.; David Wang, H.M. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Achieve Long-Lasting Senescence Inhibition in an Aging Mouse Model of Sarcopenia via Reactive Oxygen Species Scavenging and CILP2 Downregulation. In Small Science; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; p. 2500208. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, K.; Slay, B.; Knackstedt, M.; Gaharwar, A.K. Antimicrobial activity of metal and metal-oxide based nanoparticles. Adv. Therap. 2018, 1, 1700033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbine, E.O.; Rodrigues, L.d.C.; Lapa-Guimaraes, J.; Kamimura, E.S.; Corassin, C.H.; Oliveira, C.A.F.d. Application of silver nanoparticles in food packages: A review. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 39, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istiqola, A.; Syafiuddin, A. A review of silver nanoparticles in food packaging technologies: Regulation, methods, properties, migration, and future challenges. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2020, 67, 1942–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat Lazim, Z.; Salmiati, S.; Marpongahtun, M.; Arman, N.Z.; Mohd Haniffah, M.R.; Azman, S.; Yong, E.L.; Salim, M.R. Distribution of silver (Ag) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) in aquatic environment. Water 2023, 15, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Zeng, J.; Wang, X.; Drlica, K.; Zhao, X. Post-stress bacterial cell death mediated by reactive oxygen species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 10064–10071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Batal, A.I.; Attia, M.S.; Nofel, M.M.; El-Sayyad, G.S. Potential nematicidal properties of silver boron nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, in vitro and in vivo root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita) treatments. J. Clust. Sci. 2019, 30, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, L.d.O.; Macedo, E.V.; Granjeiro, J.M.; Delgado, I.F. Critical evaluation of migration studies of silver nanoparticles present in food packaging: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 3083–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Kumar, N.; Dixit, A.; Kumar, S.; Upadhyay, A. Nano Technology in Food Packaging. In Nonthermal Food Engineering Operations; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 285–317. [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna, S.S.; Balaji, K.; Pandey, S.; Rana, S. Metal oxide based nanomaterials and their polymer nanocomposites. In Nanomaterials and Polymer Nanocomposites; Elsevier Academic Press: London, UK, 2019; pp. 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, C.V.; Shin, G.H.; Kim, J.T. Metal oxide-based nanocomposites in food packaging: Applications, migration, and regulations. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 82, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtiani, E. Advancements in nanotechnology for food science and industry. Food Front. 2022, 3, 56–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maliki, R.M.; Alsalhy, Q.F.; Al-Jubouri, S.; Salih, I.K.; AbdulRazak, A.A.; Shehab, M.A.; Németh, Z.; Hernadi, K. Classification of nanomaterials and the effect of graphene oxide (GO) and recently developed nanoparticles on the ultrafiltration membrane and their applications: A review. Membranes 2022, 12, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaran, S.A.; Hassan, A.; Wahit, M.U. Materials for food packaging applications based on bio-based polymer nanocomposites: A review. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2017, 30, 143–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoială, A.; Ilie, C.-I.; Ficai, D.; Ficai, A.; Andronescu, E. Chitosan-based nanocomposite polymeric membranes for water purification—A review. Materials 2021, 14, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirugnanasambandan, T. Polymers-metal nanocomposites. In Environmental Nanotechnology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 213–254. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, S.; Muhammad, K.; Waheed, Y. Nanotechnology: A revolution in modern industry. Molecules 2023, 28, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Raina, N.; Wahi, A.; Goh, K.; Sharma, P.; Nagpal, R.; Jain, A.; Ming, L.; Gupta, M. Wound-Healing Effects of Curcumin and Its Nanoformulations: A Comprehensive Review. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, I.; Tessaro, L.; Lima, A.; Velloso, I.; Conte-Junior, C. Recent Progress in Nanotechnology Improving the Therapeutic Potential of Polyphenols for Cancer. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, Z.; Nemmar, A. Health impact of silver nanoparticles: A review of the biodistribution and toxicity following various routes of exposure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, C.; Assadpour, E.; Dima, S.; Jafari, S.M. Bioavailability and bioaccessibility of food bioactive compounds; overview and assessment by in vitro methods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 2862–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedl, J.D.; Steinbring, C.; Zaichik, S.; Le, N.M.N.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. Cellular uptake of self-emulsifying drug-delivery systems: Polyethylene glycol versus polyglycerol surface. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 1829–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paroha, S.; Chandel, A.K.S.; Dubey, R.D. Nanosystems for drug delivery of coenzyme Q10. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018, 16, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talegaonkar, S.; Bhattacharyya, A. Potential of lipid nanoparticles (SLNs and NLCs) in enhancing oral bioavailability of drugs with poor intestinal permeability. Aaps Pharmscitech 2019, 20, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severino, P.; da Silva, C.F.; Andrade, L.N.; de Lima Oliveira, D.; Campos, J.; Souto, E.B. Alginate nanoparticles for drug delivery and targeting. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 1312–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Bhardwaj, A.; Pandey, L.M. Functionalized biogenic nanoparticles for use in emerging biomedical applications: A review. Curr. Nanomater. 2021, 6, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, S.; Geoghegan, C.; Brayden, D.J. Intestinal permeation enhancers to improve oral bioavailability of macromolecules: Reasons for low efficacy in humans. Expert. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2021, 18, 273–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Choudhary, A.; Kaur, H.; Mehta, S.; Husen, A. Metal-based nanoparticles, sensors, and their multifaceted application in food packaging. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, J.O.; Fawole, O.A. Metal-based nanoparticles in food packaging and coating technologies: A review. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziarati, P.; Shirkhan, F.; Mostafidi, M.; Zahedi, M.T. A comprehensive review: Toxicity of nanotechnology in the food industry. J. Med. Discov. 2018, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Fu, P.; Aker, W.G.; Hwang, H.-M. Toxicity of engineered nanomaterials mediated by nano–bio–eco interactions. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part C 2018, 36, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdaus, J.U.; Singh, S.; Sindhu, R.K. Basics of Nano-Bioactive Compounds and Their Therapeutic Potential. In Bioactive-Based Nanotherapeutics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mohite, P.; Puri, A.; Bharati, D.; Singh, S. Polyphenol-Encapsulated Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Chronic Metabolic Diseases. In Role of Flavonoids in Chronic Metabolic Diseases: From Bench to Clinic; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 375–416. [Google Scholar]

- Theofanous, A.; Deligiannakis, Y.; Louloudi, M. Hybrids of Gallic Acid@ SiO2 and {Hyaluronic-Acid Counterpats}@ SiO2 against Hydroxyl (●OH) Radicals Studied by EPR: A Comparative Study vs. Their Antioxidant Hydrogen Atom Transfer Activity. Langmuir 2024, 40, 26412–26424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. Recent advances of polyphenol oxidases in plants. Molecules 2023, 28, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladzadabbasabadi, N.; Nafchi, A.M.; Ariffin, F.; Karim, A. Bioactive NanoBased packaging for postharvest storage of horticultural produce. In Postharvest Nanotechnology for Fresh Horticultural Produce, 1st ed.; Radhankrishnan, E.K., Ashitha, J., Sunil, P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 221–236. [Google Scholar]

- Dima, C.; Assadpour, E.; Nechifor, A.; Dima, S.; Li, Y.; Jafari, S.M. Oral bioavailability of bioactive compounds; modulating factors, in vitro analysis methods, and enhancing strategies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 8501–8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munteanu, S.B.; Vasile, C. Vegetable additives in food packaging polymeric materials. Polymers 2019, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, A.; Elder, R.S. A review of the cognitive and sensory cues impacting taste perceptions and consumption. Consum. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 4, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, M.; Okagu, O.D.; Stephens, K.; Goertzen, A.; Udenigwe, C.C. Flavour encapsulation: A comparative analysis of relevant techniques, physiochemical characterisation, stability, and food applications. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1019211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, C.; Wang, Q. Toxicity of Engineered Nanoparticles in Food: Sources, Mechanisms, Contributing Factors, and Assessment Techniques. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 13142–13158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.; Azevedo, R.; Costa, V.M.; Oliveira, S.; Preguiça, I.; Viana, S.; Reis, F.; Almeida, A.; Matafome, P.; Dias-Pereira, P.; et al. Biodistribution and intestinal inflammatory response following voluntary oral intake of silver nanoparticles by C57BL/6J mice. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 2643–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, J.; Hao, W.; Jia, G.; Chen, W.; Zheng, Y.; Qu, W.; Liu, Y. Safety assessment of nanoparticles in food: Current status and prospective. NanoToday 2021, 39, 101169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Zhang, W.; He, T.; Shu, M.; Deng, J.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Bai, J.; Lin, Q.; Luo, F.; et al. Evaluation of the Genotoxic and Oxidative Damage Potential of Silver Nanoparticles in Human NCM460 and HCT116 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamas, B.; Martins Breyner, N.; Houdeau, E. Impacts of foodborne inorganic nanoparticles on the gut microbiota-immune axis: Potential consequences for host health. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2020, 17, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Arizti, J.A.; Ventura-Gallegos, J.L.; Galván Juárez, R.E.; Ramos-Godinez, M.D.P.; Colín-Val, Z.; López-Marure, R. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles promote oxidative stress, autophagy and reduce NLRP3 in primary rat astrocytes. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 317, 108966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Sun, J.; Chang, X.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Niu, S.; Kong, L.; Zhang, T.; Wu, T.; Tang, M.; et al. Biodistribution and organ oxidative damage following 28 days oral administration of nanosilver with/without coating in mice. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2020, 40, 815–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuparu-Cretu, M.; Braniste, G.; Necula, G.-A.; Stanciu, S.; Stoica, D.; Stoica, M. Metal Oxide Nanoparticles in Food Packaging and Their Influence on Human Health. Foods 2023, 12, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Guha, P.; Srivastav, P.P. Investigating the toxicological effects of nanomaterials in food packaging associated with human health and the environment. J. Hazard. Mater. Lett. 2024, 5, 100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelescu, N.; Grigorescu, D.; Ungureanu, D.N. Silver Nanoparticles in Food Bio Packaging. A Short Review. Sci. Bull. Valahia Univ.-Mater. Mech. 2024, 20, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Hong, Z.; Han, X.; Wang, Y. Gastrointestinal exposure to silica nanoparticles induced Alzheimer’s disease-like neurotoxicity in mice relying on gut microbiota and modulation through TLR4/NF-κB and HDAC. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Du, L.; Dou, Y.; Wang, H.; Lv, M.; Wang, L.; Xiao, J.; Yin, J.; Wu, J. Orally ingested nanosilica causes liver-specific accumulation and induces liver senescence and fibrosis via the microbiota-gut-liver axis. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Cui, X.; Wu, J.; Bao, L.; Chen, C. Oral administration of silver nanomaterials affects the gut microbiota and metabolic profile altering the secretion of 5-HT in mice. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 1904–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Reyes, E.I.; Rodríguez-Ibarra, C.; Déciga-Alcaraz, A.; Díaz-Urbina, D.; Chirino, Y.I.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Food additives containing nanoparticles induce gastrotoxicity, hepatotoxicity and alterations in animal behavior: The unknown role of oxidative stress. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 146, 111814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Rodríguez, M.A.; Del Pilar Ramos-Godinez, M.; Cano-Martínez, A.; Segura, F.C.; Ruiz-Ramírez, A.; Pavón, N.; Lira-Silva, E.; Bautista-Pérez, R.; Thomas, R.S.; Delgado-Buenrostro, N.L.; et al. Food-grade titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles induce toxicity and cardiac damage after oral exposure in rats. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2023, 20, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, C.; Paula, C.D.d.; Lahbouki, S.; Meddich, A.; Outzourhit, A.; Rashad, M.; Pari, L.; Coelhoso, I.; Fernando, A.L.; Souza, V.G. Opuntia spp.: An overview of the bioactive profile and food applications of this versatile crop adapted to arid lands. Foods 2023, 12, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigbogun, I.; Mohammed, S.; Orukotan, A.; Tanko, J. The role of nanotechnology in food industries—A review. J. Adv. Microbiol. 2018, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevanandam, J.; Barhoum, A.; Chan, Y.S.; Dufresne, A.; Danquah, M.K. Review on nanoparticles and nanostructured materials: History, sources, toxicity and regulations. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2018, 9, 1050–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, D.; Cheung, W.M. Smart packaging: Opportunities and challenges. Procedia Cirp 2018, 72, 1022–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Dutt, S.; Sharma, P.; Sundramoorthy, A.K.; Dubey, A.; Singh, A.; Arya, S. Future of nanotechnology in food industry: Challenges in processing, packaging, and food safety. Glob. Chall. 2023, 7, 2200209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Huang, X.; Li, Z.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhai, X.; Shi, J.; Zhang, J.; Shen, T.; Zhang, R.; et al. Application of smart packaging in fruit and vegetable preservation: A review. Foods 2025, 14, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatlawande, A.R.; Ghatge, P.U.; Shinde, G.U.; Anushree, R.; Patil, S.D. Unlocking the future of smart food packaging: Biosensors, IoT, and nanomaterials. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 1075–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigauri, I.; Palazzo, M.; Siano, A. Examining the market potential for smart intelligent packaging: A focus on Italian consumers. Virtual Econ. 2024, 7, 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lead, J.R.; Batley, G.E.; Alvarez, P.J.; Croteau, M.N.; Handy, R.D.; McLaughlin, M.J.; Judy, J.D.; Schirmer, K. Nanomaterials in the environment: Behavior, fate, bioavailability, and effects—An updated review. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 2029–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, P.; Breen, A.; Pillai, S.C. Toxicity of nanomaterials: Exposure, pathways, assessment, and recent advances. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 2237–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athinarayanan, J.; Alshatwi, A.A.; Periasamy, V.S. Biocompatibility analysis of Borassus flabellifer biomass-derived nanofibrillated cellulose. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 235, 115961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal, M.I.; Patel, M.E.; Tye, J.; Gupta, Y. The past, present and future role of artificial intelligence in imaging. Eur. J. Radiol. 2018, 105, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.W.; Ruiz-Garcia, L.; Qian, J.P.; Yang, X.T. Food packaging: A comprehensive review and future trends. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 860–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, B.; Timilsina, H.; Bhandari, S.; Achhami, A.; Pakka, S.; Shrestha, P.; Kandel, D.; Gc, D.B.; Khatri, S.; Chhetri, P.M. Current trends of food analysis, safety, and packaging. Int. J. Food Sci. 2021, 2021, 9924667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, M.R.; Hsieh, S.; Ricacho, N. Innovative food packaging, food quality and safety, and consumer perspectives. Processes 2022, 10, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalai, A.; Harini, K.; Pallavi, P.; Gowtham, P.; Girigoswami, K.; Girigoswami, A. Nanotechnology driven improvement of smart food packaging. Mater. Res. Innov. 2023, 27, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, M.S.; Schlogl, A.E.; Estanislau, F.R.; Souza, V.G.L.; dos Reis Coimbra, J.S.; Santos, I.J.B. Nanotechnology in packaging for food industry: Past, present, and future. Coatings 2023, 13, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerorsa, G.B.; Pal, M. An Overview of Nanotechnology-Based Innovations in Food Packaging. In Nano-Innovations in Food Packaging; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2022; pp. 3–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan, P.; Sethi, A.; Singla, M.; Bhardwaj, D.; Kaur, B. Nanotechnology in Food: Advances in Processing, Packaging, Safety, and Emerging Challenges. J. Food Chem. Nanotechnol. 2025, 11, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthu, A.; Nguyen, D.H.; Neji, C.; Törős, G.; Ferroudj, A.; Atieh, R.; Prokisch, J.; El-Ramady, H.; Béni, Á. Nanomaterials for Smart and Sustainable Food Packaging: NanoSensing Mechanisms, and Regulatory Perspectives. Foods 2025, 14, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stramarkou, M.; Boukouvalas, C.; Koskinakis, S.E.; Serifi, O.; Bekiris, V.; Tsamis, C.; Krokida, M. Life cycle assessment and preliminary cost evaluation of a smart packaging system. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.; Fahmy, H.; Salah, S. Application of interactive and intelligent packaging for fresh fish shelf-life monitoring. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 677884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnianto, M.; Poerwanto, B.; Wahyono, A.; Apriliyanti, M.; Lestari, I. Monitoring of banana deteriorations using intelligent-packaging containing brazilien extract (Caesalpina sappan L.). In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Deshmukh, R.K.; Gaikwad, K.K. Functional Agents from Agro-Waste for Active and Intelligent Food Packaging. In Agro-Waste Derived Biopolymers and Biocomposites: Innovations and Sustainability in Food Packaging; Kumar, S., Mukherjee, A., Katiyar, V., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 205–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahanian, S. Implementing Artificial Intelligence in the Evaluation of Packaging Distribution and Label Design Modeling. Ph.D. Thesis, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Trejo Beltran, D.Y. Barriers and Drivers to Adoption of IoT-Enhanced Smart Packaging in the Food Supply Chain. Master’s Thesis, University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, A.; Kant, K. Smart sensing, communication, and control in perishable food supply chain. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw. (TOSN) 2020, 16, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butuc, O.; Akkerman, R.; de Leeuw, S. Smart packaging adoption in fresh fruits and vegetables supply chains. Intern. J. Logist. Manag. 2025, 36, 284–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.; Sun, D.-W.; Zhu, Z. Recent developments in intelligent packaging for enhancing food quality and safety. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2650–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhusudan, P.; Chellukuri, N.; Shivakumar, N. Smart packaging of food for the 21st century—A review with futuristic trends, their feasibility and economics. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 21018–21022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakopoulos, G.; Varga, P.; Gutt, T.; Schneider, G.; Ehm, H.; Hoess, A.; Tauber, M.; Karathanasopoulou, K.; Lackner, A.; Delsing, J. Industry 5.0: Research areas and challenges with artificial intelligence and human acceptance. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2024, 18, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Function | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|

| Active Packaging | Interacts with the food to extend shelf life | Oxygen scavengers, moisture absorbers, antimicrobial films |

| Intelligent/Smart Packaging | Monitors condition of food or environment | Freshness indicators, time-temperature indicators, RFID tags |

| Edible/Functional Packaging | Consumable films with bioactive compounds | Nutraceutical delivery, edible coatings |

| Biodegradable/Green Packaging | Environmentally friendly | Biopolymers like polylactic acid (PLA), starch-based films |

| Indicator | Mechanism | What It Detects | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH Indicator | Color change due to chemical reaction with acids/bases | Spoilage (ammonia, lactic acid) | Anthocyanin-based labels |

| Time-Temperature Indicator (TTI) | Chemical or enzymatic reaction that progresses with time & temperature | Cumulative heat exposure | 3MTM MonitorMarkTM |

| Gas Indicator | Reaction with volatile compounds | Oxygen, CO2, ethylene, spoilage gases | Freshness sensors in meat packaging |

| Moisture Indicator | Changes in color or conductivity with humidity | Water activity, mold growth | Ink-based moisture strips |

| Sensor Type | Principle | Examples | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Sensors | Detect specific analytes via reaction | pH sensors, gas sensors | Freshness, spoilage detection |

| Biosensors | Use biological molecules for detection | Enzyme, antibody, DNA-based sensors | Pathogen detection, toxin monitoring |

| Physical Sensors | Measure temperature, pressure, light | Thermochromic inks, RFID | TTI, cold chain monitoring |

| Optical Sensors | Colorimetric or fluorescence change | Color-changing labels | Spoilage, freshness |

| Brand/Company | Product/Technology | Type of Smart Packaging | Indicator/Sensor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3M | MonitorMarkTM | TTI Label | Time-temperature indicator |

| Tetra Pak | Freshness Indicator | Intelligent packaging | pH/gas indicator |

| Sealed Air | Cryovac® Freshness | Active and intelligent | Oxygen scavenger and gas sensor |

| Insignia Technologies | Ink-based labels | Intelligent packaging | Colorimetric freshness sensor |

| Zest Labs | Zest Fresh | IoT-based sensor | Ethylene detection and freshness tracking |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dimopoulou, M.; Graikou, K.; Chinou, I.; Gortzi, O. A Review of Nanotechnology in Food, Smart Packaging and Potential Public Health Impact. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010168

Dimopoulou M, Graikou K, Chinou I, Gortzi O. A Review of Nanotechnology in Food, Smart Packaging and Potential Public Health Impact. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010168

Chicago/Turabian StyleDimopoulou, Maria, Konstantia Graikou, Ioanna Chinou, and Olga Gortzi. 2026. "A Review of Nanotechnology in Food, Smart Packaging and Potential Public Health Impact" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010168

APA StyleDimopoulou, M., Graikou, K., Chinou, I., & Gortzi, O. (2026). A Review of Nanotechnology in Food, Smart Packaging and Potential Public Health Impact. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010168