Are We Really Training at the Desired Intensity? Concurrent Validity of 16 Commercial Photoplethysmography-Based Heart Rate Monitors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Testing Procedures

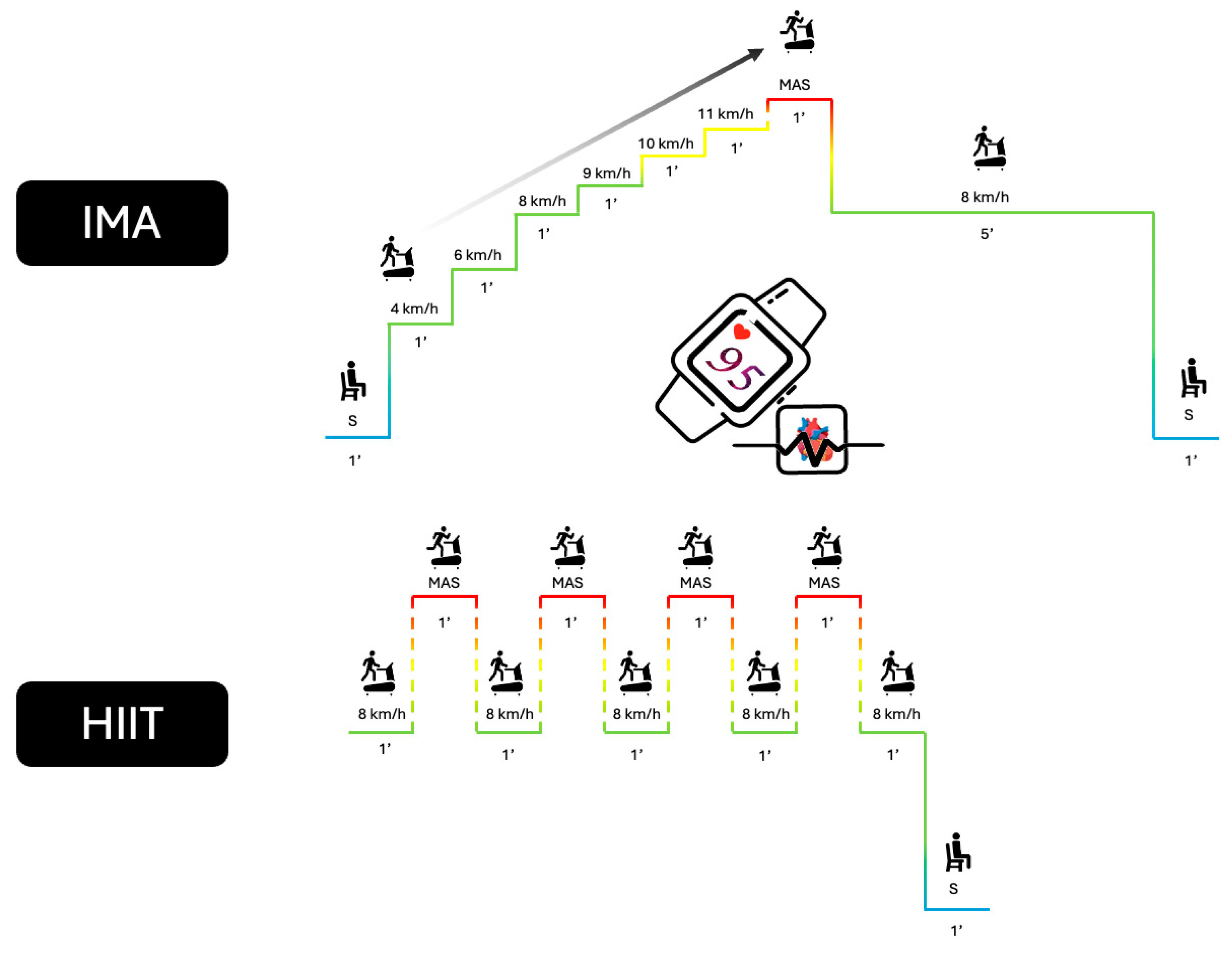

2.3.2. Incremental Maximal Aerobic Test (IMA)

2.3.3. High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) Test

2.3.4. Measurement Equipment and Data Acquisition

2.3.5. Data Processing

2.3.6. Statistical Analyses

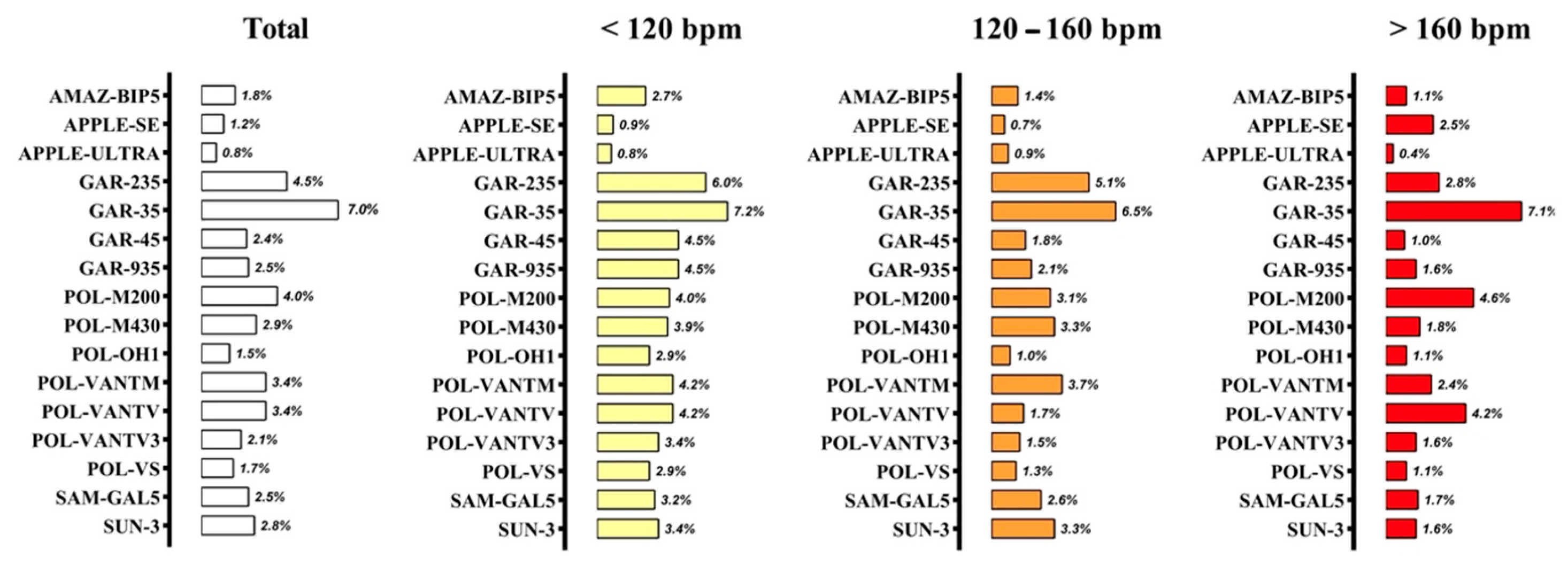

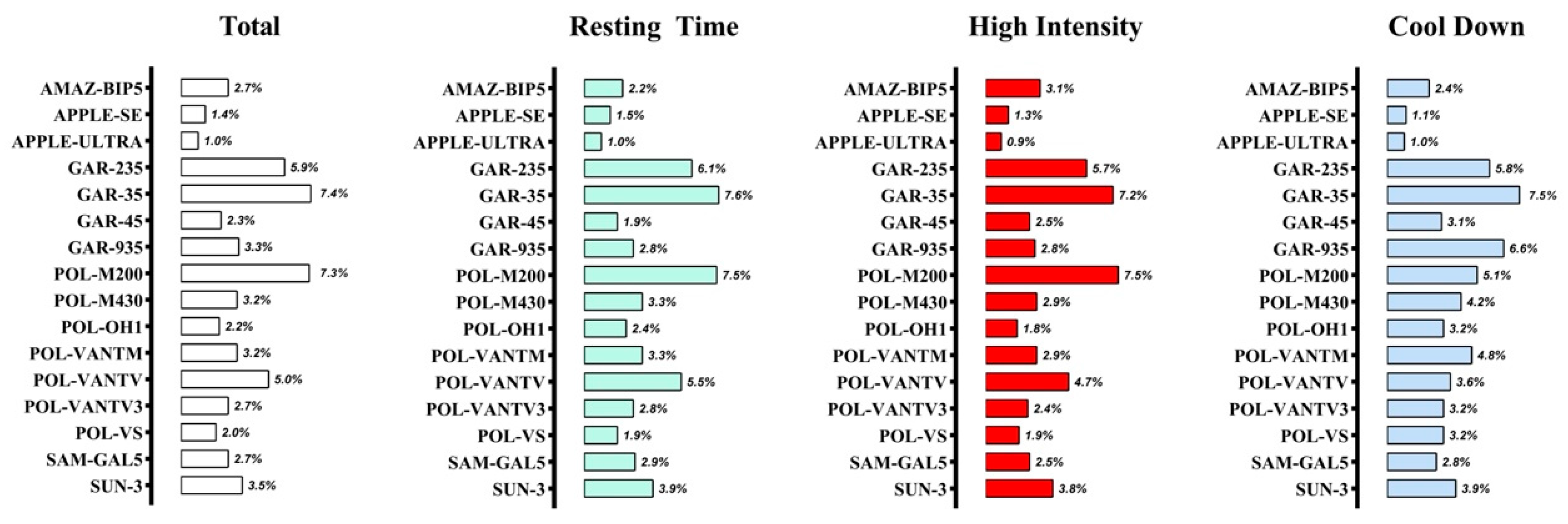

- The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) (1,k, one-way random effects, absolute agreement, multiple raters/measurements model) were calculated according to the guidelines presented by Koo and Li [27]. Moreover, ICCs were interpreted as <0.50, poor; 0.50–0.75, moderate; 0.75–0.90, good; >0.90, excellent [27].

- The standard error of measurement (SEM) was calculated from the square root of the mean square error term in a repeated-measures analysis of variance [28]. The results were presented both in absolute (beat·min−1) and relative terms as a coefficient of variation (CV = 100 SEM/mean). For most sporting events, exercise performance tests, and sport technologies, CV should be lower than 5% [29,30].

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Achten, J.; Jeukendrup, A.E. Heart Rate Monitoring Applications and Limitations. Sports Med. 2003, 33, 517–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, K.S.; Kjerland, G.Ø. Quantifying training intensity distribution in elite endurance athletes: Is there evidence for an “optimal” distribution? Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2006, 16, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, S.E.; An, H.S.; Dinkel, D.M.; Noble, J.M.; Lee, J.M. How accurate are the wrist-based heart rate monitors during walking and running activities? Are they accurate enough? BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2016, 2, e000106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spierer, D.K.; Rosen, Z.; Litman, L.L.; Fujii, K. Validation of photoplethysmography as a method to detect heart rate during rest and exercise. J. Med. Eng. Technol. 2015, 39, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J. Photoplethysmography and its application in clinical physiological measurement. Physiol. Meas. 2007, 28, R1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, S.; Martinez, A.; Arias, S.; Lozano, A.; Gonzalez, M.P.; Dietze-Hermosa, M.S.; Boyea, B.L.; Dorgo, S. Commercial Smart Watches and Heart Rate Monitors: A Concurrent Validity Analysis. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2023, 37, 1802–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alugubelli, N.; Abuissa, H.; Roka, A. Wearable Devices for Remote Monitoring of Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability—What We Know and What Is Coming. Sensors 2022, 22, 8903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Malagón, E.; Ruiz-Alias, S.; García-Pinillos, F.; Delgado-García, G.; Soto-Hermoso, V.M. Comparison between photoplethysmographic heart rate monitor from Polar Vantage M and Polar V800 with H10 chest strap while running on a treadmill: Validation of the Polar Precision Prime™ photoplestimographic system. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part P J. Sports Eng. Technol. 2021, 235, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, M.; Clark, A.; De La Rosa, A. The Polar® OH1 Optical Heart Rate Sensor is Valid during Moderate-Vigorous Exercise. Sports Med. Int. Open 2018, 2, E67–E70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Belmonte, Ó.; Febles-Castro, A.; Gay, A.; Cuenca-Fernandez, F.; Arellano, R.; Ruiz-Navarro, J.J. Validity of the polar verity sense during swimming at different locations and intensities. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2023, 33, 2623–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, I.T.; Hanoun, S.; Nahavandi, D.; Nahavandi, S. Validation of Polar OH1 optical heart rate sensor for moderate and high intensity physical activities. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navalta, J.W.; Montes, J.; Bodell, N.G.; Salatto, R.W.; Manning, J.W.; DeBeliso, M. Concurrent heart rate validity of wearable technology devices during trail running. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, E.; Lewis, K.; Directo, D.; Kim, M.J.Y.; Dolezal, B.A. Validation of biofeedback wearables for photoplethysmographic heart rate tracking. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2016, 15, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caminal, P.; Sola, F.; Gomis, P.; Guasch, E.; Perera, A.; Soriano, N.; Mont, L. Validity of the Polar V800 monitor for measuring heart rate variability in mountain running route conditions. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 118, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, J.A.; Wells, E.K.; Manor, J.P.; Webster, M.J. Evaluation of Earbud and Wristwatch Heart Rate Monitors during Aerobic and Resistance Training. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2019, 12, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Støve, M.P.; Haucke, E.; Nymann, M.L.; Sigurdsson, T.; Larsen, B.T. Accuracy of the wearable activity tracker Garmin Forerunner 235 for the assessment of heart rate during rest and activity. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, E.E.; Golaszewski, N.M.; Bartholomew, J.B. Estimating accuracy at exercise intensities: A comparative study of self-monitoring heart rate and physical activity wearable devices. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017, 5, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Blackburn, G.; Desai, M.; Phelan, D.; Gillinov, L.; Houghtaling, P.; Gillinov, M. Accuracy of wrist-worn heart rate monitors. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, A.; Vagedes, J. How accurate is pulse rate variability as an estimate of heart rate variability?: A review on studies comparing photoplethysmographic technology with an electrocardiogram. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 166, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckay, A.K.A.; Stellingwerff, T.; Smith, E.S.; Martin, D.T.; Mujika, I.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L.; Sheppard, J.; Burke, L.M. Defining training and performance caliber: A participant classification framework. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2022, 17, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallarés, J.G.; Cerezuela-Espejo, V.; Morán-Navarro, R.; Martínez-Cava, A.; Conesa, E.; Courel-Ibáñez, J. A New Short Track Test to Estimate the VO2max and Maximal Aerobic Speed in Well-Trained Runners. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 1216–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilgen-Ammann, R.; Schweizer, T.; Wyss, T. RR interval signal quality of a heart rate monitor and an ECG Holter at rest and during exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 119, 1525–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.M.; Doust, J.H. A 1% treadmill grade most accurately reflects the energetic cost of outdoor running. J. Sports Sci. 1996, 14, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerezuela-Espejo, V.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Morán-Navarro, R.; Martínez-Cava, A.; Pallarés, J.G. The relationship between lactate and ventilatory thresholds in runners: Validity and reliability of exercise test performance parameters. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, M.; Laursen, P.B. High-intensity interval training, solutions to the programming puzzle: Part I: Cardiopulmonary emphasis. Sports Med. 2013, 43, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallarés, J.G.; Morán-Navarro, R.; Ortega, J.F.; Fernández-Elías, V.E.; Mora-Rodriguez, R. Validity and reliability of ventilatory and blood lactate thresholds in well-trained cyclists. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163, Erratum in J. Chiropr. Med. 2017, 16, 346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2017.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkison, R.R.; Nevill, A. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med. 1998, 26, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G. Measures of Reliability in Sports Medicine and Science. Sports Med. 2000, 30, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Martínez-Cava, A.; Morán-Navarro, R.; Escribano-Peñas, P.; Chavarren-Cabrero, J.; González-Badillo, J.J.; Pallarés, J.G. Reproducibility and Repeatability of Five Different Technologies for Bar Velocity Measurement in Resistance Training. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 47, 1523–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icenhower, A.; Murphy, C.; Brooks, A.K.; Irby, M.; N’dah, K.; Robison, J.; Fanning, J. Investigating the accuracy of Garmin PPG sensors on differing skin types based on the Fitzpatrick scale: Cross-sectional comparison study. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1553565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajj-Boutros, G.; Landry-Duval, M.A.; Comtois, A.S.; Gouspillou, G.; Karelis, A.D. Wrist-worn devices for the measurement of heart rate and energy expenditure: A validation study for the Apple Watch 6, Polar Vantage V and Fitbit Sense. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2023, 23, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbina, A.; Mikael Mattsson, C.; Waggott, D.; Salisbury, H.; Christle, J.W.; Hastie, T.; Wheeler, M.T.; Ashley, E.A. Accuracy in wrist-worn, sensor-based measurements of heart rate and energy expenditure in a diverse cohort. J. Pers. Med. 2017, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillinov, S.; Etiwy, M.; Wang, R.; Blackburn, G.; Phelan, D.; Gillinov, A.M.; Houghtaling, P.; Javadikasgari, H.; Desai, M.Y. Variable accuracy of wearable heart rate monitors during aerobic exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 1697–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olstad, B.H.; Zinner, C. Validation of the Polar OH1 and M600 optical heart rate sensors during front crawl swim training. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bent, B.; Goldstein, B.A.; Kibbe, W.A.; Dunn, J.P. Investigating sources of inaccuracy in wearable optical heart rate sensors. NPJ Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düking, P.; Giessing, L.; Frenkel, M.O.; Koehler, K.; Holmberg, H.C.; Sperlich, B. Wrist-worn wearables for monitoring heart rate and energy expenditure while sitting or performing light-to-vigorous physical activity: Validation study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e16716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaneda, D.; Esparza, A.; Ghamari, M.; Soltanpur, C.; Nazeran, H. A review on wearable photoplethysmography sensors and their potential future applications in health care. Int. J. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 4, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Company | Model | Acronym | Position | Data Processing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amazfit | Bip 5 | AMAZ-BIP5 | Wrist | APP Zepp |

| Apple | Watch SE | APPLE-SE | Wrist | APP Apple Fitness+ |

| Apple | Watch ultra | APPLE-ULTRA | Wrist | APP Apple Fitness+ |

| Garming | Forerunner 235 | GAR-235 | Wrist | Garmin Connect |

| Garming | Forerunner 35 | GAR-35 | Wrist | Garmin Connect |

| Garming | Forerunner 45 | GAR-45 | Wrist | Garmin Connect |

| Garming | Forerunner 935 | GAR-935 | Wrist | Garmin Connect |

| Polar | M200 | POL-M200 | Wrist | Polar FlowSync |

| Polar | M430 | POL-M430 | Wrist | Polar FlowSync |

| Polar | OH1 | POL-OH1 | Arm | Polar FlowSync |

| Polar | Vantage M | POL-VANTM | Wrist | Polar FlowSync |

| Polar | Vantage V | POL-VANTV | Wrist | Polar FlowSync |

| Polar | Vantage V3 | POL-VANTV3 | Wrist | Polar FlowSync |

| Polar | Verity Sense | POL-VS | Arm | Polar FlowSync |

| Samsung | Galaxy watch 5 | SAM-GAL5 | Wrist | APP Samsung Health |

| Suunto | 3 Fitness | SUN-3 | Wrist | APP Suunto |

| Device | Intensity | Agreement | Magnitude of Error | Data Lost and Refined | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC | BIAS(SD) | SEM | Lost % | Refined % | ||

| AMAZ-BIP5 | Total | 0.997 | −1 (3) | 2 | 2.5 | 4.5 |

| <120 lat·min−1 | 0.979 | −2 (5) | 4 | |||

| 120–160 lat·min−1 | 0.985 | 0 (3) | 2 | |||

| >160 lat·min−1 | 0.983 | 0 (2) | 1 | |||

| APPLE-SE | Total | 0.999 | 0 (1) | 2 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| <120 lat·min−1 | 0.998 | 0 (2) | 1 | |||

| 120–160 lat·min−1 | 0.996 | 0 (1) | 1 | |||

| >160 lat·min−1 | 0.899 | −1 (5) | 3 | |||

| APPLE- ULTRA | Total | 1.000 | 0 (1) | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| <120 lat·min−1 | 0.998 | 0 (1) | 1 | |||

| 120–160 lat·min−1 | 0.994 | 0 (2) | 1 | |||

| >160 lat·min−1 | 0.997 | 0 (1) | 1 | |||

| GAR-235 | Total | 0.982 | 0 (9) | 7 | 0.0 | 6.4 |

| <120 lat·min−1 | 0.947 | −1 (9) | 6 | |||

| 120–160 lat·min−1 | 0.828 | 3 (10) | 7 | |||

| >160 lat·min−1 | 0.787 | −2 (7) | 5 | |||

| GAR-35 | Total | 0.944 | −3 (14) | 10 | 9.5 | 16.3 |

| <120 lat·min−1 | 0.852 | 0 (11) | 8 | |||

| 120–160 lat·min−1 | 0.744 | 2 (13) | 9 | |||

| >160 lat·min−1 | 0.161 | −11 (13) | 12 | |||

| GAR-45 | Total | 0.995 | 0 (4) | 3 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| <120 lat·min−1 | 0.931 | −3 (8) | 6 | |||

| 120–160 lat·min−1 | 0.978 | 0 (3) | 2 | |||

| >160 lat·min−1 | 0.990 | 0 (2) | 1 | |||

| GAR-935 | Total | 0.994 | 0 (5) | 4 | 0.4 | 1.3 |

| <120 lat·min−1 | 0.965 | −1 (7) | 5 | |||

| 120–160 lat·min−1 | 0.958 | 1 (5) | 3 | |||

| >160 lat·min−1 | 0.940 | 0 (4) | 3 | |||

| POL-M200 | Total | 0.984 | −2 (8) | 6 | 0.0 | 2.2 |

| <120 lat·min−1 | 0.974 | −1 (6) | 4 | |||

| 120–160 lat·min−1 | 0.919 | −1 (6) | 5 | |||

| >160 lat·min−1 | 0.603 | −4 (10) | 7 | |||

| POL-M430 | Total | 0.992 | −1 (6) | 4 | 0.2 | 1.1 |

| <120 lat·min−1 | 0.975 | −1 (6) | 4 | |||

| 120–160 lat·min−1 | 0.918 | −1 (7) | 5 | |||

| >160 lat·min−1 | 0.916 | −2 (4) | 3 | |||

| POL-OH1 | Total | 0.998 | −1 (3) | 2 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| <120 lat·min−1 | 0.985 | −1 (5) | 4 | |||

| 120–160 lat·min−1 | 0.991 | 0 (2) | 2 | |||

| >160 lat·min−1 | 0.972 | −1 (3) | 2 | |||

| POL-VANTM | Total | 0.989 | −1 (7) | 5 | 0.0 | 1.6 |

| <120 lat·min−1 | 0.979 | −1 (7) | 5 | |||

| 120–160 lat·min−1 | 0.898 | 0 (8) | 5 | |||

| >160 lat·min−1 | 0.867 | −2 (6) | 4 | |||

| POL-VANTV | Total | 0.989 | −2 (7) | 5 | 0.0 | 0.8 |

| <120 lat·min−1 | 0.973 | −1 (7) | 5 | |||

| 120–160 lat·min−1 | 0.976 | −1 (4) | 3 | |||

| >160 lat·min−1 | 0.673 | −5 (9) | 7 | |||

| POL-VANTV3 | Total | 0.996 | −1 (4) | 3 | 0.0 | 1.4 |

| <120 lat·min−1 | 0.969 | −2 (6) | 4 | |||

| 120–160 lat·min−1 | 0.983 | 0 (3) | 2 | |||

| >160 lat·min−1 | 0.973 | −1 (3) | 2 | |||

| POL-VS | Total | 0.997 | 0 (3) | 2 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| <120 lat·min−1 | 0.976 | −1 (5) | 4 | |||

| 120–160 lat·min−1 | 0.988 | 0 (2) | 2 | |||

| >160 lat·min−1 | 0.986 | 0 (2) | 1 | |||

| SAM-GAL5 | Total | 0.994 | 2 (4) | 3 | 1.3 | 2.5 |

| <120 lat·min−1 | 0.969 | 0 (6) | 4 | |||

| 120–160 lat·min−1 | 0.950 | 3 (4) | 3 | |||

| >160 lat·min−1 | 0.951 | 1 (3) | 2 | |||

| SUN-3 | Total | 0.993 | 2 (6) | 4 | 0.0 | 1.4 |

| <120 lat·min−1 | 0.979 | 1 (6) | 4 | |||

| 120–160 lat·min−1 | 0.921 | 2 (7) | 5 | |||

| >160 lat·min−1 | 0.932 | 2 (4) | 3 | |||

| Device | Intensity | Agreement | Magnitude of Error | Data Lost and Refined | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC | BIAS(SD) | SEM | Lost % | Refine % | ||

| AMAZ-BIP5 | Total | 0.977 | −1 (6) | 4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Resting time | 0.987 | 1 (5) | 3 | |||

| High intensity | 0.925 | −4 (6) | 5 | |||

| Cool down | 0.978 | 4 (3) | 3 | |||

| APPLE-SE | Total | 0.997 | 0 (3) | 2 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Resting time | 0.997 | 0 (3) | 2 | |||

| High intensity | 0.990 | −1 (3) | 2 | |||

| Cool down | 0.997 | 0 (2) | 1 | |||

| APPLE- ULTRA | Total | 0.999 | 0 (2) | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Resting time | 0.999 | 0 (2) | 1 | |||

| High intensity | 0.996 | −1(2) | 1 | |||

| Cool down | 0.998 | 1 (2) | 1 | |||

| GAR-235 | Total | 0.889 | −5 (12) | 9 | 0.1 | 1.8 |

| Resting time | 0.918 | −7 (12) | 10 | |||

| High intensity | 0.719 | −6 (12) | 9 | |||

| Cool down | 0.880 | 6 (10) | 8 | |||

| GAR-35 | Total | 0.841 | −9 (14) | 12 | 6.8 | 12.7 |

| Resting time | 0.879 | −10 (13) | 12 | |||

| High intensity | 0.702 | −10 (12) | 11 | |||

| Cool down | 0.834 | 8 (13) | 11 | |||

| GAR-45 | Total | 0.984 | 0 (5) | 4 | 2.4 | 0.0 |

| Resting time | 0.991 | 1 (4) | 3 | |||

| High intensity | 0.953 | −2 (6) | 4 | |||

| Cool down | 0.974 | 5 (4) | 4 | |||

| GAR-935 | Total | 0.967 | 0 (7) | 5 | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| Resting time | 0.982 | 0 (6) | 4 | |||

| High intensity | 0.938 | −2 (6) | 5 | |||

| Cool down | 0.836 | 9 (10) | 10 | |||

| POL-M200 | Total | 0.875 | −8 (14) | 12 | 0.0 | 1.6 |

| Resting time | 0.898 | −8 (15) | 12 | |||

| High intensity | 0.747 | −9 (14) | 12 | |||

| Cool down | 0.936 | 1 (10) | 7 | |||

| POL-M430 | Total | 0.971 | −2 (7) | 5 | 0.0 | 0.8 |

| Resting time | 0.976 | −1 (7) | 5 | |||

| High intensity | 0.947 | −4 (5) | 5 | |||

| Cool down | 0.958 | 7 (5) | 6 | |||

| POL-OH1 | Total | 0.988 | −1 (5) | 4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Resting time | 0.990 | −1 (5) | 4 | |||

| High intensity | 0.982 | −2 (4) | 3 | |||

| Cool down | 0.973 | 5 (4) | 5 | |||

| POL-VANTM | Total | 0.967 | −1 (7) | 5 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Resting time | 0.975 | 0 (7) | 5 | |||

| High intensity | 0.943 | −4 (5) | 5 | |||

| Cool down | 0.907 | 7 (7) | 7 | |||

| POL-VANTV | Total | 0.935 | −6 (10) | 8 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Resting time | 0.942 | −6 (11) | 9 | |||

| High intensity | 0.885 | −7 (8) | 8 | |||

| Cool down | 0.960 | 3 (7) | 5 | |||

| POL-VANTV3 | Total | 0.979 | −1 (6) | 4 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Resting time | 0.983 | 0 (6) | 5 | |||

| High intensity | 0.955 | −4 (4) | 4 | |||

| Cool down | 0.972 | 5 (4) | 5 | |||

| POL-VS | Total | 0.987 | 0 (5) | 3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Resting time | 0.992 | 1 (4) | 3 | |||

| High intensity | 0.971 | −3 (4) | 3 | |||

| Cool down | 0.973 | 5 (4) | 5 | |||

| SAM-GAL5 | Total | 0.975 | 0 (6) | 4 | 1.7 | 0.0 |

| Resting time | 0.978 | 1 (6) | 5 | |||

| High intensity | 0.944 | −1 (6) | 4 | |||

| Cool down | 0.974 | 4 (3) | 4 | |||

| SUN-3 | Total | 0.961 | −1 (8) | 6 | 0.3 | 2.4 |

| Resting time | 0.963 | −2 (9) | 6 | |||

| High intensity | 0.941 | 0 (7) | 6 | |||

| Cool down | 0.946 | 2 (7) | 6 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Oropesa, P.; Sánchez-Pay, A.; Conesa-Ros, E.; Bianco, A.; Ruiz-Navarro, J.J.; Martínez-Cava, A. Are We Really Training at the Desired Intensity? Concurrent Validity of 16 Commercial Photoplethysmography-Based Heart Rate Monitors. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010126

Oropesa P, Sánchez-Pay A, Conesa-Ros E, Bianco A, Ruiz-Navarro JJ, Martínez-Cava A. Are We Really Training at the Desired Intensity? Concurrent Validity of 16 Commercial Photoplethysmography-Based Heart Rate Monitors. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010126

Chicago/Turabian StyleOropesa, Pablo, Alejandro Sánchez-Pay, Elena Conesa-Ros, Antonino Bianco, Jesús J. Ruiz-Navarro, and Alejandro Martínez-Cava. 2026. "Are We Really Training at the Desired Intensity? Concurrent Validity of 16 Commercial Photoplethysmography-Based Heart Rate Monitors" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010126

APA StyleOropesa, P., Sánchez-Pay, A., Conesa-Ros, E., Bianco, A., Ruiz-Navarro, J. J., & Martínez-Cava, A. (2026). Are We Really Training at the Desired Intensity? Concurrent Validity of 16 Commercial Photoplethysmography-Based Heart Rate Monitors. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010126