1. Introduction

Considering the development of the coastal real estate market [

1] on the Polish coast, it can be concluded that it is conditioned by the provisions of the Spatial Planning and Development Act [

2]. Through the provisions of the Act on the maritime areas of the Republic of Poland and the maritime administration, a more detailed legal act was introduced, i.e., the spatial development plan for the internal maritime waters, the territorial sea and the exclusive economic zone of the Baltic Sea [

3]. In the identification context, these maritime areas have become a reference to coastal areas, i.e., areas directly adjacent to some of the most valuable lands in each country. Although there are no official guidelines for classifying localities in Polish Pomerania as coastal areas, it is generally accepted that the location of seaside properties should not exceed 2 to 5 km from the baseline. In reality, coastal areas are associated with the administrative areas of coastal municipalities. Therefore, these areas are not just a few or a dozen kilometers from the sea, but sometimes several dozen kilometers. This orientation offers greater sales opportunities, as it is no trivial fact that a seaside location offers a great chance of a return on invested capital with minimal individual risk [

4]. Therefore, disseminating such information, even through popular social media, guarantees success in terms of interest in these areas [

5]. However, it should be emphasized that currently, locating investments in seaside towns, i.e., towns with direct access to the sea or very close to the shoreline, is becoming almost impossible [

6]. The development there is quite dense and finding a gap or a building fill is problematic. Currently, the definition of a seaside resort is also highly individual and rather associated with a group of cities that have more convenient transport links to the sea [

7,

8].

When analyzing the location of seaside properties, it should be noted that areas directly on the seaside are characterized by very rapid development rates and a high level of attractiveness. This is due to the high interest of potential investors in areas with high investment potential, commonly referred to as “economic growth poles.” Seaports and marinas play a key role here, setting the development direction for adjacent areas [

9] due to greater access to water. Therefore, the specificity of the seaside location plays a significant role in the socio-economic development of the country. It is also a driving force in the development of tourism and recreation. Of course, the point hierarchy dominates here, as it is difficult to determine whether the entire South Baltic zone fits the theory of economic growth poles. Regionally, this is likely the case, but growth itself is fastest in specific points, called poles, often associated with leading seaports [

10].

Typically, these rapidly growing points in Pomerania are coastal cities, particularly port cities and towns with seaports. This stems from the fact that the maritime sector plays a special role in the process of economic growth. It stimulates society to act for economic growth in the local market, and at the same time shapes the region’s settlement system. This influences the overall level of developing location conditions, which include: labor force, research and development institutionalism, attractive landscape, transport infrastructure, service availability, political and business climate, and spatial and urban benefits [

11].

Among the aforementioned factors, people play the most important role, shaping the urban system. However, many publications emphasize place, or locus. This influences the functionality of the local real estate market. Its orientation is primarily determined by human inclinations in terms of socio-economic development. The driving industry, which stimulates the region’s growth and controls the rate of point growth, remains a priority. However, sometimes, as in the case of coastal properties, the main driving force also turns out to be the connection with the environment and a location on the Baltic Sea. This location is considered a strategic location, also in the context of investment location [

12]. A seaside location offers significant development opportunities, and the capital resulting from geographic rent is a strength of coastal areas, including the coastal real estate market.

These considerations determine the need to undertake research related to the continuous human intervention in increasing the development potential of the Polish coastal zone, primarily the West Pomeranian and Pomeranian Voivodeships. This is evident in key investments carried out in these areas, such as the recent efforts to launch the first nuclear power plant in Choczewo, or strengthening the potential of the seaports in Gdynia, Gdańsk, Szczecin, and Świnoujście, as well as strengthening the military role of other regions, such as the operation of the anti-missile shield in Redzikowo, the construction of an anti-missile shield by launching another naval missile unit in Siemirowice, or even the construction of service bases for offshore wind farms. While these recent investments are numerous, there is no mention of the potential for unexpected threats, which are known to exist but are not analyzed in terms of “what if” [

13]. However, considering the initiation of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, for example, there was no indication that the crisis situation could overwhelm not only Wuhan but also all communities around the world. Therefore, presenting threats as global problems should prompt reflection among decision-makers, including a reassessment of current investment decisions [

14].

Undertaking research in this area, particularly in terms of considering various types of threats in analyses of investment propensity, represents a unique approach to demonstrating the directionality of human capital implementation in risky areas. Furthermore, the impact of dumped chemical weapons, with elements of GIS simulations, is a new issue, not previously addressed in the literature related to the real estate market and investments in the South Baltic region. This is confirmed by the European Union’s Munitions in the Baltic Sea Mapping Project (MUNIMAP), which is aimed at developing and implementing solutions for the detection, risk assessment, and safe neutralization of underwater munitions. This stems from the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction, a treaty concluded by 193 states. The result of these activities was the development of a European Parliament Resolution in 2021 regarding the formulation of plans for the removal of dumped chemical weapons from the Baltic Sea.

2. Materials and Methods

When analyzing the impact of global threats on the coastal real estate market, it is important to remember that the current threat landscape is quite extensive and that new threats, previously unconsidered, are constantly emerging. Threats usually appear unexpectedly, making it very difficult to respond from the outset, especially since we sometimes lack sufficient knowledge about them. Examples include the crisis surrounding the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 virus or, currently, the constantly evolving armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine.

This reinforces the belief that investment analyses should always consider all aspects, not only economic but also significant military, political, and humanitarian factors, and above all, geographic ones, which, supported by innovative simulations, can protect people from tragedy. Investment trends are also constantly evolving, shifting as capital is deployed in sometimes previously unexplored territory. This poses a significant risk and a challenge for long-term decision-making. Therefore, the directions taken to define potential threats globally can significantly contribute to changes in the perception of potential development zones and curb the uncontrolled development of threats in this area.

The main objective of this article is to demonstrate the impact of potential global threats on the investment process in the Polish coastal region, taking into account the rapidly developing real estate market. The research problem is formulated as the following question: In these times of uncertainty, should various types of risks be considered in investing, given the element of threat that influences human existentialism? The research hypothesis of this study is formulated as follows: various types of risks in the South Baltic region should reflect a threat variable in their design, influencing the propensity to invest in areas of potential threat.

The main objective of this article is to demonstrate the impact of potential global threats on the investment process in the Polish coastal strip. Based on the above, an analysis of threats in the Baltic Sea region was conducted, preceded by a review of literature and online data, including industry portals of the International Maritime Organization and HELCOM, the Helsinki Commission—the Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission, operating under the Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area of 9 April 1992.

The research process was divided into two parts. The first part involved a secondary analysis of literature sources and statistical data. This method allowed for the analysis of the types of threats in the Baltic Sea region, including the obtained data on the impact of these threats on the natural environment. Next, using a case study approach, the main threats to the natural environment, including the coastal real estate market, were classified and the impact of selected threats on the development of investments in the coastal zone was assessed. Due to the complexity of the work involved in presenting multiple threats in one study, it was considered appropriate to review directly the sections related to each threat.

The research process in the second part focused on GIS analyses, including: flood and erosion changes and their impact on the sea baseline, as well as changes resulting from the threats associated with the dumping of chemical weapons in the Baltic Sea and their impact on coastal areas within the Polish coast. The study focuses on Poland’s Central Coast, where continuous sea erosion has been observed for many years, and its effects are visible within the operating seaports of the Central Coast. The accumulative aspect of the seashore concerns areas located within the port of Świnoujście. Therefore, due to data availability, the study presents changes within the ports of Kołobrzeg and Darłowo, which record the highest transshipment volumes, considering smaller seaports. In this part, the main emphasis was placed on the selection of research tools and GIS processing of spatial data, using geostatistical interpolation elements [

15].

Therefore, the spline method with barriers was used to depict erosion changes. This method uses a mathematical function to estimate the points, minimizing the overall surface curvature, resulting in a smooth surface. The method fits the mathematical function to a specified number of input points, passing through so-called sample points. The research results were processed in cartographic form. Simulations of threats related to the dumping of chemical weapons in the Baltic Sea were determined by generating the centroid of polygonal representations of the threat area. Based on the resulting layer, a heatmap interpolation was performed, based on the proximity and density of the dumped chemical weapons. For comparative purposes, the results were additionally verified using the Inverse Distance Weighting method, which uses weighted averages of values measured at points near the interpolation point as the basis for interpolation. The Operational Graphics Package with electronic map cells and an implemented digital terrain model was used to generate high-water simulations within the ports. The geostatistical analyses used available GIS data from the Helkom platform.

The simulation studies were based on profiles of sea baseline changes monitored between 1875 and 1979, 1960 and 1983, and 2000 and 2010 at the base of the dune, as well as a digital terrain model of the monitored area with photogrammetric characteristics available in the results of coastal inspections conducted by the Supreme Audit Office and data from the documentation of the seashore condition of government institutions in Poland. Simulations of coastal changes resulting from the impact of sea erosion on the shore and the impact of chemical weapons dumped in the Baltic Sea on the surrounding area were performed based on smooth interpolation of vectorized measurement points plotted on the DTM (Digital Terrain Model) substructure.

3. Contemporary Threats to the Coastal Real Estate Market

3.1. Erosion and Storm Threats in the South Baltic Sea

Considering the terrain and development of the South Baltic coast over the past few decades, it can be considered an active area of significant economic, tourist, and recreational importance. The main driving force in the development of industry and all services is the expanding port complexes of Świnoujście-Szczecin and Gdańsk-Gdynia. Continuous human interference in the development of Poland’s coastal belt is also visible from the investment perspective, for example, due to the decision to build the first nuclear power plant in Poland. The investment process at the coast is undoubtedly influenced by the significant development of the Gdańsk and Szczecin metropolitan areas, which significantly influence the development of transport corridors to the south, constituting a key link in the supply chain. However, despite the visible development of the coastal zone, there are also constantly increasing environmental changes in the aforementioned area. This primarily concerns the impact of sea rise and climatic anomalies, which contribute to the degradation of the seashore.

Problems related to the impact of erosion on the coastal coast are the subject of ongoing research [

16,

17,

18,

19], which indicates that erosion is associated with an increased number and frequency of strong storms [

20,

21,

22,

23] and accelerated sea level rise [

24,

25,

26,

27]. This fact affects the entire structure of Poland’s coastal zone [

28,

29,

30], which is largely an open coastline with a length of 498 km. Furthermore, the length of cliffs in Poland is approximately 100 km [

31,

32], which contributes to landscape destruction by sea waves [

33], despite the presence of barriers such as high dunes and narrow, low barriers migrating landward.

Considering the impact of destructive sea waves on the development of coastal infrastructure, it should be emphasized that the frequency of storms and the rate of sea level rise have increased in recent decades [

34,

35,

36]. This is confirmed by reports of the Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission [

37,

38], according to which the occurrence of storms in the Baltic Sea is driven by large-scale, multi-decadal changes. This fact is also confirmed by studies of changes in the position of the shoreline in the Polish coastal zone of the Southern Baltic [

28,

29,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Based on these studies, it was found that the average rate of shoreline retreat was approximately 0.5–2 m/year, depending on the location and period of measurements [

44,

45,

46].

However, the average rate of coastal retreat during the 145 years between 1875 and 2020 was not constant over time. During the first 83 years (1875–1958), the average shoreline retreat was only 0.3 m/year. The rate of shoreline retreat during the six analyzed periods between 1958 and 2020 varied significantly, from 0.6 to 7.7 m/year. The fastest coastal retreat, approximately 7.7 m/year, occurred between 2001 and 2005 [

47].

This trend also confirms the erosion of coastlines by sea waves in other countries, such as Denmark, where erosion is increasing at a rate of up to 3–5 m per year [

48]. Therefore, considering erosion as a globalization threat, it should be noted that investment decisions should take into account its impact on coastal buildings and structures. This is especially true given that, according to archival data from institutions monitoring the condition of the Polish coast, coastal infrastructure is constantly at risk of degradation due to sea waves, with annual land loss exceeding 22 hectares and growing [

49]. This is, of course, also due to climate change, which is felt in all human activities [

50,

51,

52]. This includes the growing flood risk, which influences rising water levels, which in turn increases the rate of erosion [

53]. This situation poses a significant threat to residents of coastal towns. Therefore, inappropriate management of land as a technical and protective belt by humans can lead to irreversible consequences [

28,

54,

55]. An example of this is the simulation of erosion changes around the seaports of Darłowo (

Figure 1a) and Kołobrzeg (

Figure 1b).

The figures above depict a simulation of changes in the sea baseline around the ports of Darłowo and Kołobrzeg, the line where the sea meets the land. The simulation, conducted over a two-decade period and taking into account the observed rate of change, reinforces the belief that coastal urban areas are at risk from marine intrusion. Given the current trend of preventing erosion, i.e., resurfacing beaches near coastal towns, ports, and marinas, this may not be sufficient.

3.2. Storm Threats in the Polish Coastal Zone

Erosion threats are inextricably linked to the occurrence of storm floods, backwaters, and, consequently, the flooding of coastal areas. Storm floods and the aforementioned backwaters are difficult to control and are incidental events that, unfortunately, cause significant damage that is difficult to control. History shows many examples of water intrusion into urban areas, irreversibly damaging buildings, as evidenced by Niechorze on the Polish coast. An example of the destructive effects of the sea is a simulation of storm floods and the flooding of the coastal area near the ports of Darłowo (

Figure 2a,b) and Kołobrzeg (

Figure 2c,d) due to high water levels in the context of climate warming and sea level rise (

Figure 2).

From the analyzed examples of coastal flooding simulations around the Darłowo and Kołobrzeg seaports, it can be concluded that water ingress is dependent on the high coastal dunes, but also on the installed port protection devices, i.e., storm gates [

56]. In the context of installing such devices, the obstacle is, of course, the river, which was the reason for the construction of the ports themselves. Therefore, installing such barriers makes no sense due to the water accumulation. Therefore, the only solution to saving coastal areas and avoiding costly damage later is to maintain the seashore at an appropriate level and continuously reinforce it, and to prevent the port from being used for residential purposes, which exposes residents to the destructive effects of sea waves.

Unfortunately, this last argument does not convince decision-makers, and numerous examples of poor construction practices can be observed in both Darłowo and Kołobrzeg. The global erosion threat is unlikely to be a basis for investment planning. The above is likely influenced by the constant interest in tourist infrastructure and the unwavering demand for seaside real estate. The only noticeable effect is the stimulation of public awareness and the projection of what may happen in the future [

57]. The uncontrolled development of seaside tourist and recreational infrastructure itself may lead to an even greater concentration of buildings without taking into account the forces of nature and may become the cause of many construction disasters [

58,

59].

3.3. Chemical Threats in the South Baltic Zone

From an ecological perspective, one of the greatest problems in the entire Baltic Sea basin is the chemical weapons dumped during World War II. Their quantity and the extent to which they remain on the seabed to this day are only rough estimates. However, as available publications indicate, there are approximately 32,000 tons of chemical weapons dumped in the Baltic Sea, including approximately 11,000 tons of chemical warfare agents and approximately 2000 tons of chemical munitions [

60]. Dumping operations at sea were carried out at various times during the war to prevent them from being captured by the enemy [

61]. Considerable quantities of chemical weapons were dumped in the Skagerrak Strait and the Atlantic Ocean, but the Baltic Sea was the site of the largest dump. Historians estimate that the dumping of chemical agents likely continued until the early 1980s [

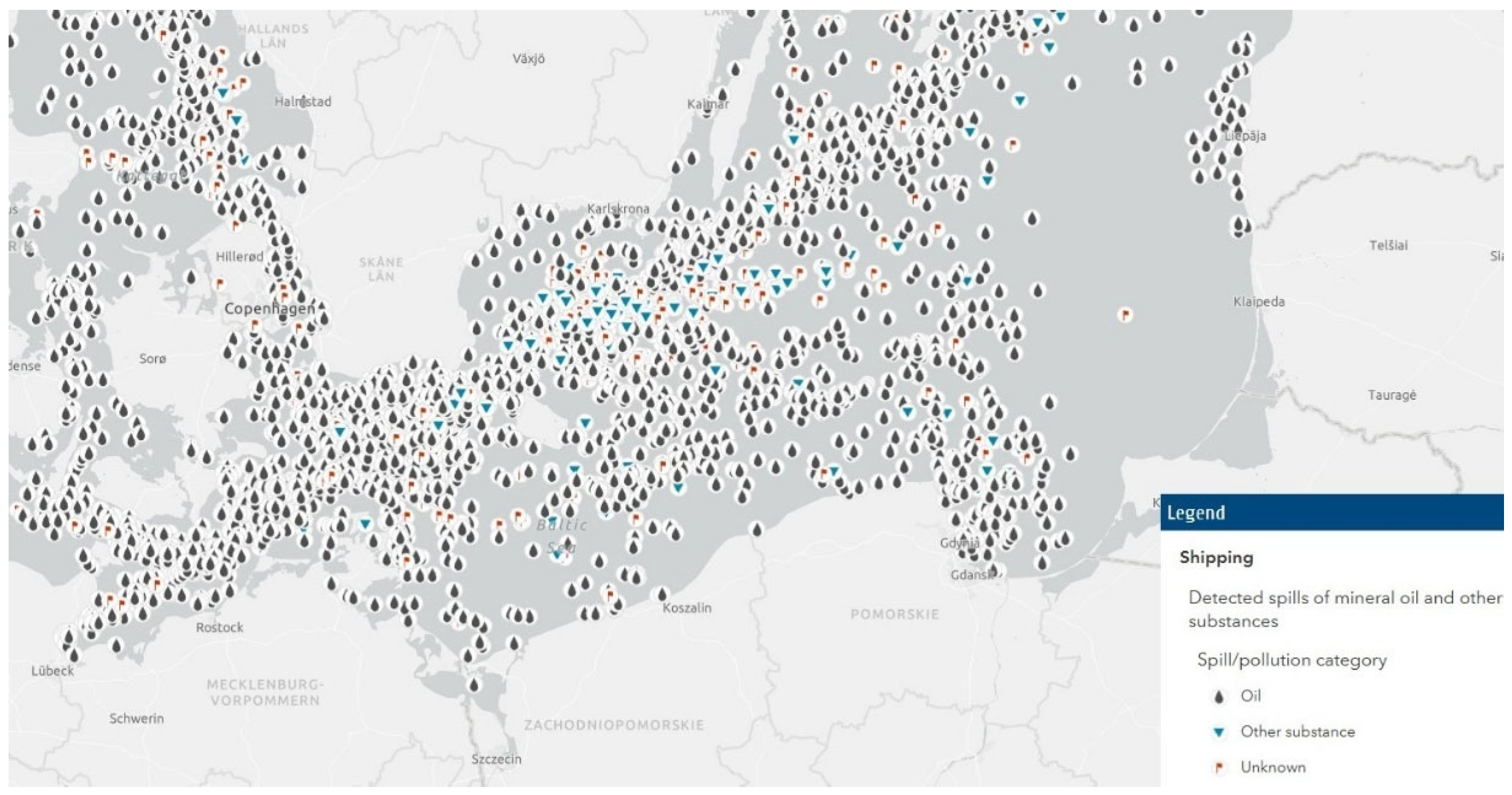

61]. The locations of chemical weapons dumped are shown in the figure below (

Figure 3).

When considering the main chemical weapon dumping sites, it is worth noting that these were the deepest locations, i.e., the Bornholm Deep, the Gotland Deep, and the Gdansk Deep [

62]. The largest amount of mustard gas is sulfur mustard (7027 tons in the Bornholm Deep and 608 tons in the Gotland Deep), which occurs in the form of dropped aircraft bombs and artillery shells [

59]. Other agents in the dumped ammunition and containers included Clark I (Chlorine-Arsenic-Kampfstoff), a substance causing nausea, vomiting, and headaches, and potentially leading to pulmonary edema, and Adamsite, an organoarsenic chemical compound used as tear gas and an irritant chemical agent that strongly irritates mucous membranes, causing severe chest pain and breathing difficulties. In addition to the chemicals mentioned, the areas also contain α-chloroacetophenone, also known as tear gas (approximately 600 tons) and hydrogen cyanide (approximately 80 tons) [

59].

The threats presented pose a significant ecological problem and also impact human health, which consequently impacts social life throughout the entire Baltic Sea basin [

63,

64,

65]. The release of chemicals into the sea, in addition to contaminating living organisms, also poses a potential threat to rivers, which serve as a drainage basin, including groundwater. This, in turn, leads to the recognition of dumped chemical weapons as a potential global threat, as it affects not only a single region but, as in the case of Poland, the entire coastal strip (

Figure 4).

3.4. Threats of Seawater Contamination

When analyzing global threats affecting the development of the coastal real estate market, it is undoubtedly important to recognize that pollution resulting from shipping itself is among the leading threats. Ship traffic has a significant impact on the initiation of chemical pollution [

66,

67]. Examples include polyaromatic hydrocarbons such as pyrene, which are carcinogenic compounds produced during combustion, and high concentrations of which are found along shipping routes [

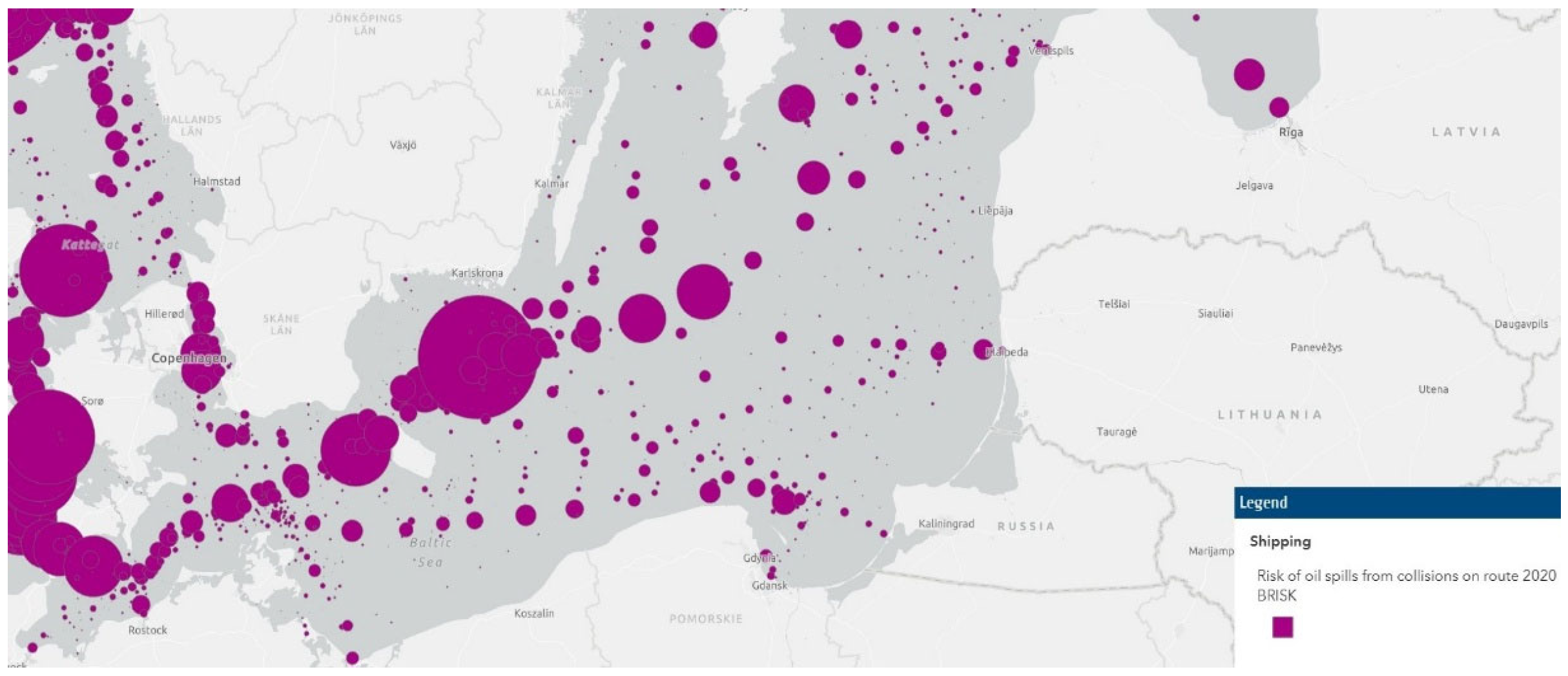

68]. Of course, there are many chemicals, although the largest amounts are attributed to petroleum derivatives, which pollute the main maritime highways from the Danish Straits to Saint Petersburg.

Available analyses indicate that tankers entering the Baltic Sea through the narrow and difficult-to-navigate straits of the Øresund, Little Belt, Great Belt, Kattegat, and Skagerrak carry over 100 million tons of crude oil annually. Identified spills, as well as smaller, unidentified ones, can release enormous quantities of oil into the sea, with irreversible consequences. It is estimated that a large number of spills occur in the Baltic Sea every year, caused by accidents or illegal operational discharges (

Figure 5).

The increasing amount of pollution is related to the increased volume of vessel traffic in the Baltic Sea, including the constantly developing transport corridors. Their development, despite its positive benefits related to the development of the maritime economy, impacts the coastal ecology and the development of the coastal zone of the untouched areas of the central Polish coast. Despite the low port activity between the Gdynia-Gdańsk and Świnoujście-Szczecin port complexes, pollution occurring in this zone is similar to that of large seaports located there, with a simultaneous increase in the risk of pollution towards the Polish coast (

Figure 6).

4. Tendency to Invest in the Coastal Real Estate Market

When considering the Polish coastal market, it is worth noting that both the Pomeranian and West Pomeranian Voivodeships are significant investment destinations in Poland. This stems from their geographic location, where geographic rent enhances the area’s character. According to the fDi Intelligence European Cities and Regions of the Future ranking, the Pomeranian Voivodeship ranked fifth among the most attractive investment destinations in Europe in the Mid-Sized European Regions of the Future 2023 category (

Table 1).

Unfortunately, the West Pomeranian Voivodeship was not included in this ranking, reinforcing the belief that these are different investment markets. However, in the European Cities and Regions of the Future rankings prepared by fDi Intelligence, the metropolitan cities of Szczecin and Gdańsk were among the top cities and regions with the highest development potential. The selection criteria included economic potential, human capital, profitability, transport links, and business friendliness.

The comparability of these two voivodeships stems from their location on the Baltic Sea; in particular, both form part of the European Baltic Sea Region. Due to its location across the voivodeships, the South Baltic Arc, often referred to as the Via Hanseatica transport corridor, also forms part of the framework. The conceptual framework for this corridor was outlined in the VASAB 2010 document. A significant strength of both voivodeships is their relatively long coastline, which in the case of the Pomeranian Voivodeship provides access to the Bay of Gdańsk, and in the case of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, to the Bay of Pomerania.

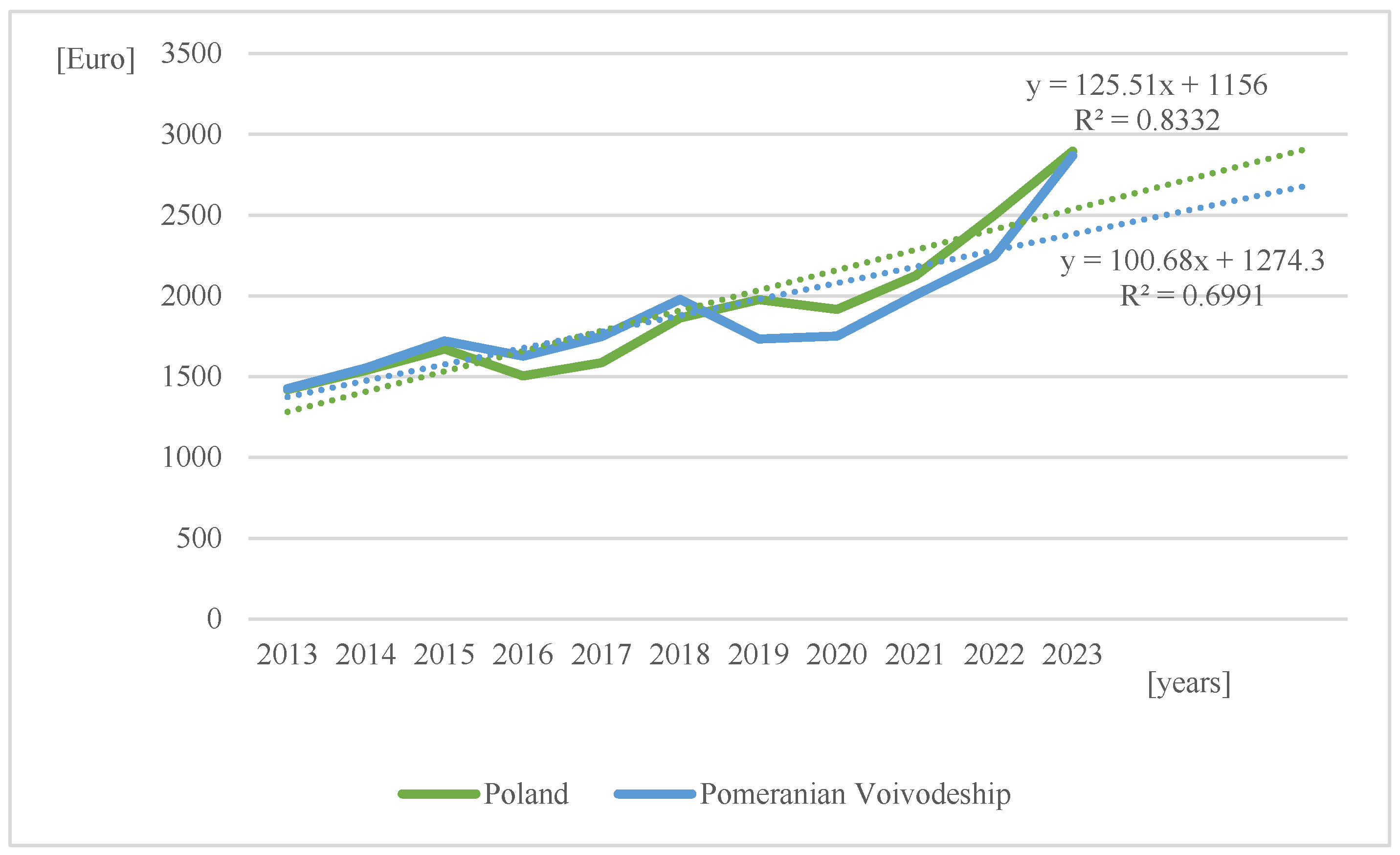

Due to their prominent coastal locations, the Pomeranian and West Pomeranian voivodeships are multifunctional. All types of economic functions have developed there, with the maritime economy at the forefront, as well as specialized services of supraregional importance. The Gdańsk and Szczecin agglomerations undoubtedly lead the way here. Thanks to the expanding metropolises, the per capita investment rate in the Pomeranian Voivodeship (Pomorskie) continues to rise (

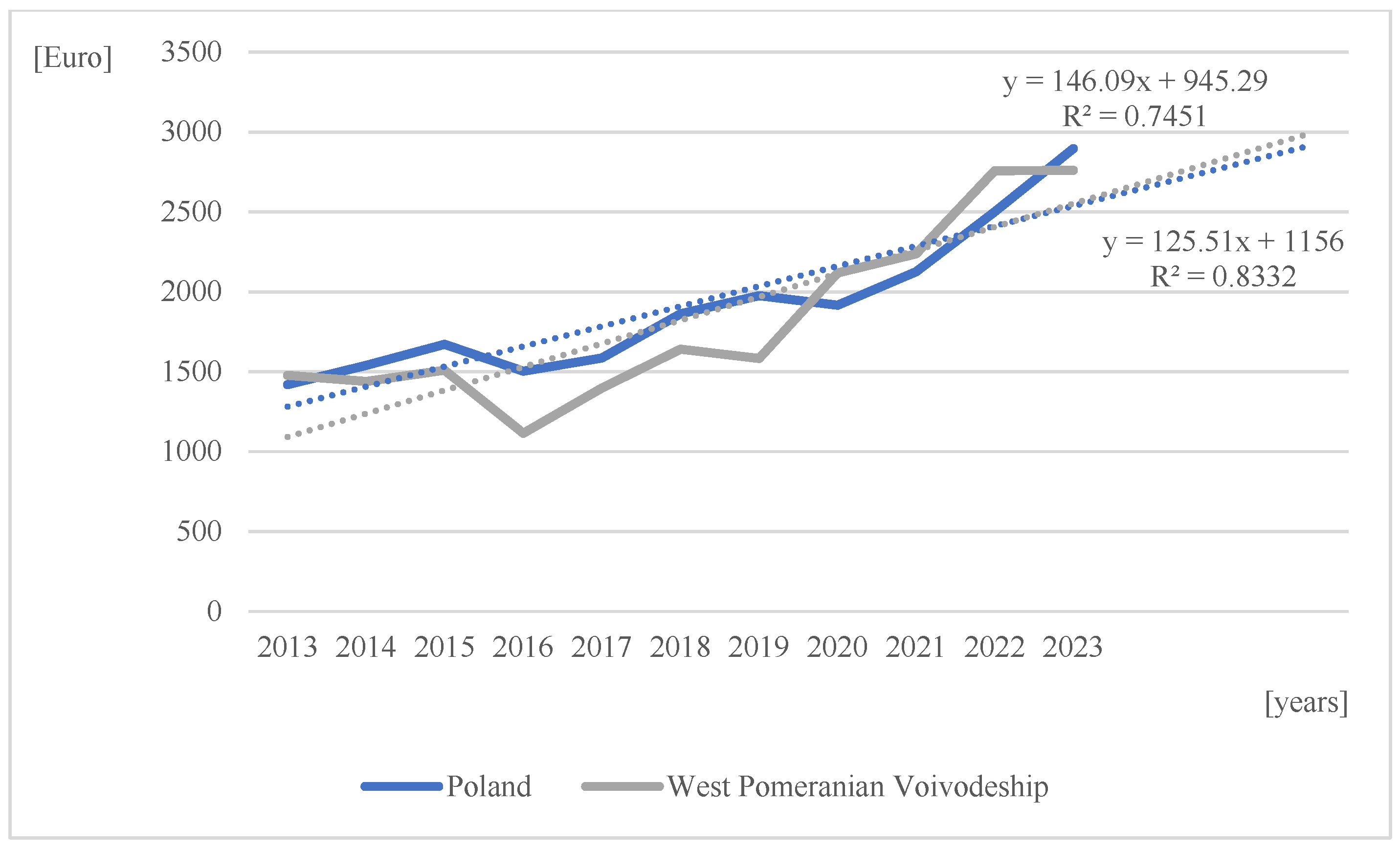

Figure 7).

As the figure above shows, capital expenditures per capita in the Pomeranian Voivodeship have been steadily increasing over the past decade. This confirms the previous analysis regarding the attractiveness of the Pomeranian Voivodeship for investment. This indicator is primarily driven by the development of new systemic sources of electricity production in the voivodeship, such as a gas-steam power plant (450 MW) in Gdańsk, and the launch of the first Polish nuclear power plant (min. 2000 MW, max. 3750 MW) in one of the two locations under consideration: Lubiatowo-Kopalino (Choczewo commune) or Żarnowiec (Gniewino and Krokowa communes). It is already noticeable how residents’ incomes are changing, indicating affluence compared to the rest of Poland (

Figure 8).

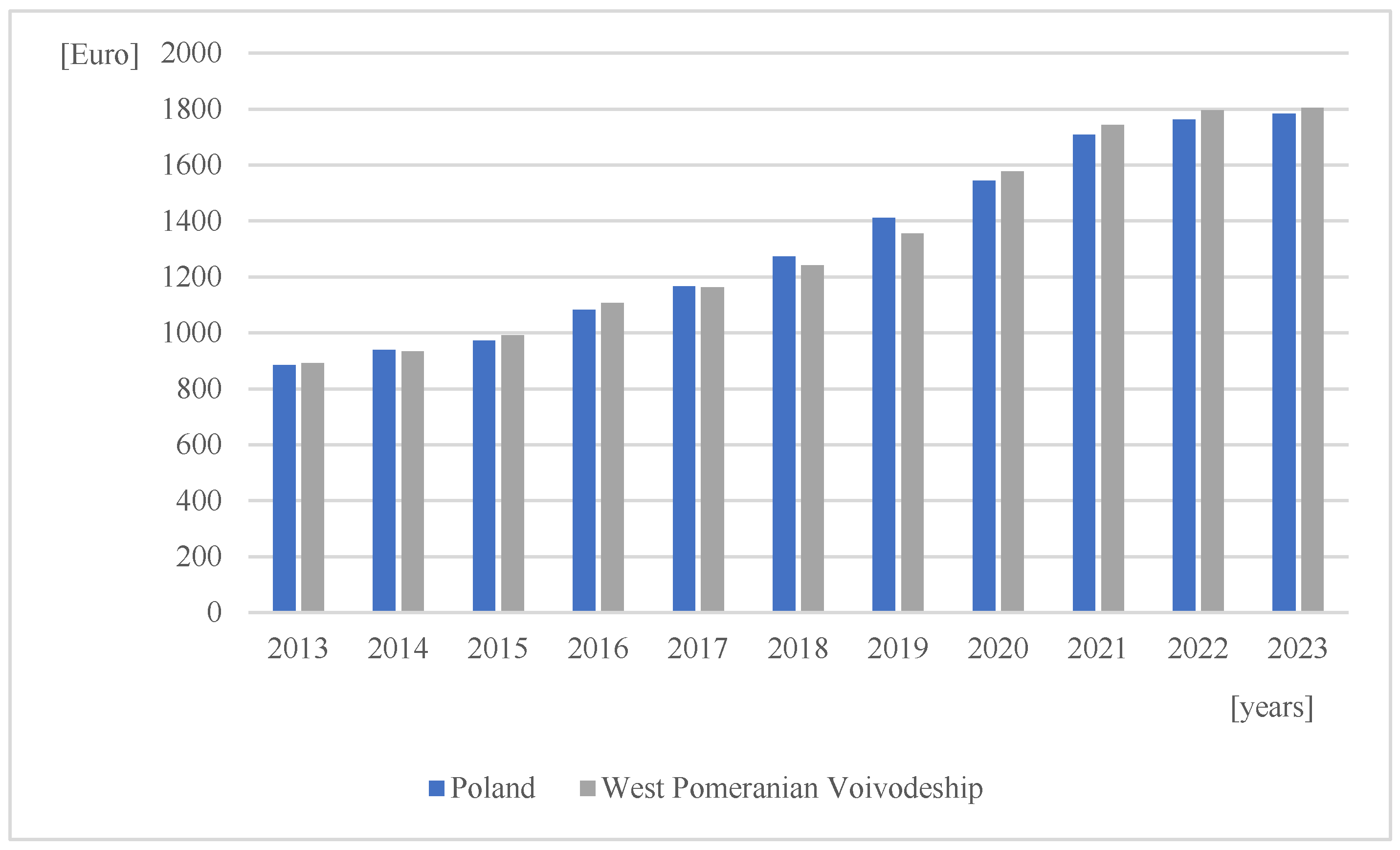

Analyzing investment in the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, it can be concluded that it is developing at a similar pace to the Pomeranian Voivodeship, with a significant slowdown during the initiation of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in Poland during the pandemic. The investment rate here is undoubtedly related to the maritime sector, primarily due to the oil port and the remoteness of the seaports of Świnoujście and Szczecin, which have larger port facilities (

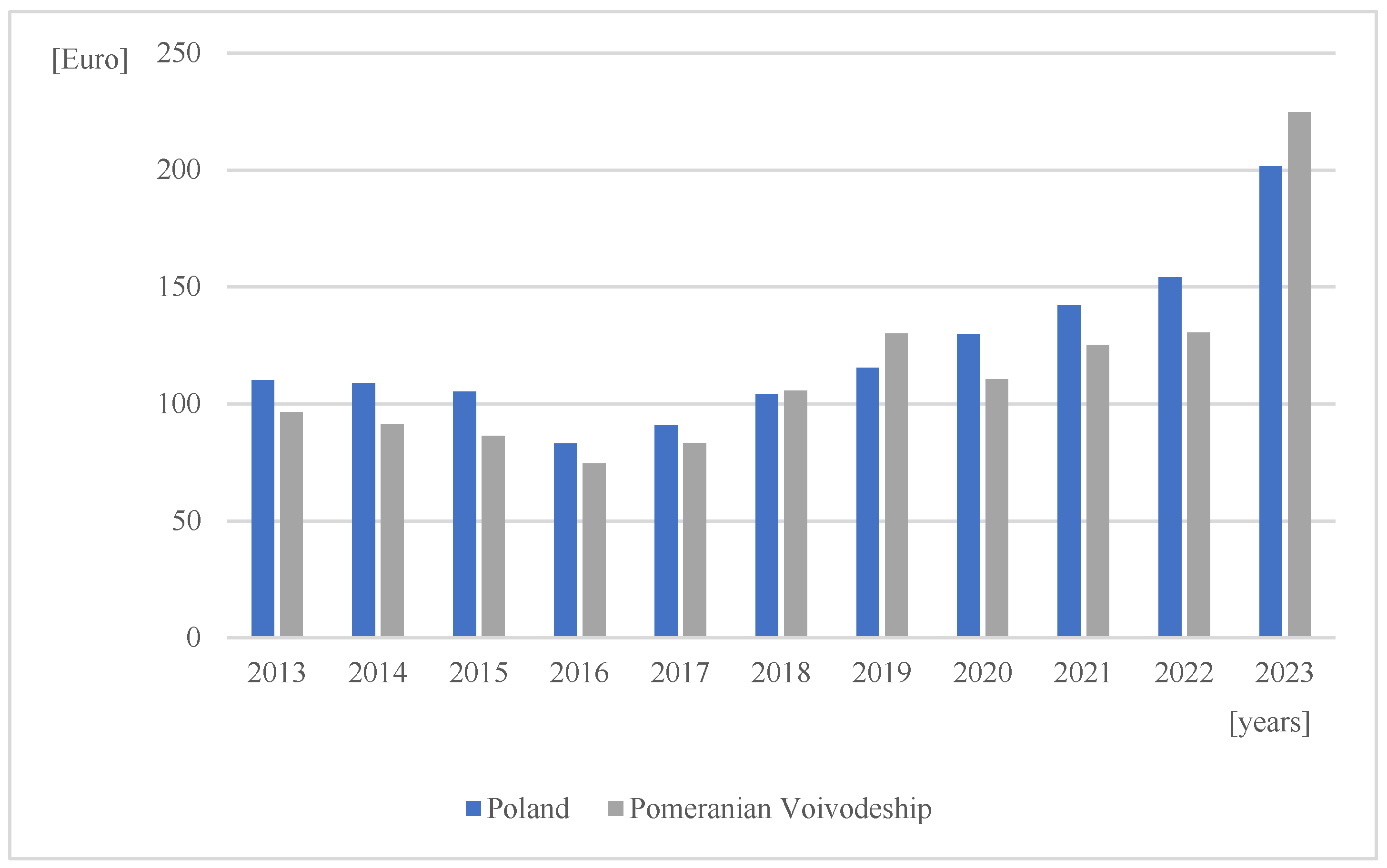

Figure 9).

As the chart above shows, capital expenditures are steadily increasing, at a rate similar to that of the Pomeranian Voivodeship. This indicator is supported by the development of the Świnoujście seaport, particularly the increase in fuel transshipment, as well as the development of the wind farm market, which fuels the regional economy. The deepening of the Świnoujście-Szczecin shipping channel from 10.5 m to 12.5 m undoubtedly influenced the wealth and income of residents, which ultimately led to the creation of new jobs and the development of a new logistics area capable of competing with western seaports (

Figure 10).

The above is complemented by the voivodeship wealth ranking presented by the Ministry of Finance, showing the tax revenue indicators per capita for individual voivodeships, constituting the basis for calculating the annual amounts of the equalization part of the general subsidy and payments for 2024, determined according to the principles set out in the Act of 13 November 2003 on the income of local government units [

69],

Table 2.

5. Conclusions

Analyzing the globalization of threats in the Baltic Sea basin and the propensity to invest on the Polish coast, based on the above analyses, it was concluded that coastal areas are affected by numerous threats that may have irreversible consequences for construction. This applies to the real estate market, related to the growing tourism and recreation industry, as well as the development of coastal municipalities and the livelihoods of residents, which are at risk [

70]. The direction of threats will be focused on the outflow of capital and, consequently, on a slowdown in investment, which in the long term will predict a minimization of the labor market, the marginalization of highly attractive locations, and ultimately, forced changes in the local community’s livelihood [

71]. In the context of the fulfillment of life functions of the people living there, this will be associated with a tragedy for households. The threats presented, including those related to marine water contamination resulting from the dumping of chemical weapons, excessive amounts of petroleum products, and the current erosion of the coast, underscore their importance and also indicate the need to take immediate steps to counteract disasters. While there is considerable interest in environmental issues in the Baltic Sea, insufficient results are currently visible [

72]. Therefore, overdeveloped areas should be treated separately from towns located on cliffs, ports, and harbors, as well as sparsely populated areas within the technical and protective zones.

Considering the propensity to invest, it is surprising that despite awareness of the existence and impact of the various threats presented, the development process in the coastal zone remains high [

73]. New development and coastal development planning contradict common sense. This is obviously due to the fact that port and port-adjacent areas already being developed lack new land, so investors seeking new locations invest in areas with high risk. The investment argument often trumps common sense, as is the case with ports and marinas, where the purpose of a port is often overlooked—primarily transshipment. In summary, it should be stated that the hypothesis that contemporary global threats to the real estate market have a significant impact on the development of threat awareness and are inversely proportional to the decision to allocate capital in coastal areas has been correctly formulated [

74]. The research hypothesis of the study was therefore confirmed that different types of risks in the South Baltic area should reflect the threat variable in their structure, influencing the propensity to invest in the area of potential threat. The research results also confirmed the rather trivial maxim that the coastal real estate market is highly specific. The widely held theory that the real estate market is the most imperfect of all imperfect markets is valid in this respect [

75].

This is particularly evidenced by the fact that, despite growing forecasts of a steady retreat of the coastline and irreversible loss of land in the coastal zone, as well as the impact of chemical weapons threats and contamination risks resulting from increased amounts of petroleum substances in the sea, investments are steadily growing and are becoming drivers of coastal development. The contradiction between theory and common sense is not synonymous with the conditions and aspirations of decision-makers. Thus, the main goal of the article, namely to demonstrate the impact of potential global threats on the investment process in the Polish coastal zone, has been achieved, and an affirmative answer to the question, “In these times of uncertainty, should various types of risks be considered in investing, bearing in mind the element of threat affecting human existentialism?”, should be considered as highly relevant in similar markets located in the Baltic Sea basin. The above theses are also supported by the literature, which, based on photogrammetric studies, leads to conclusions related to the socio-economic evolution of coastal municipalities in the context of changes in the dynamics of coastal urbanization. These analyses constitute a fundamental element in understanding the dynamics of land use, taking into account aspects such as urban expansion, changes in the use of coastal areas, and the direction of coastal development [

76,

77,

78].

It is difficult to verify from an economic perspective why, despite being aware of such serious threats, people continue to invest [

79]. Should we therefore refer to philosophy in this situation and refer to the residual, that is, a psychological phenomenon, consisting of ideas and beliefs that express the drives that drive people to certain behaviors [

80]. Not everything in human behavior is always obvious. Professor Hozer writes about this, identifying inclinations with the economic dimension. According to his theory, the accumulation of attributes that potential real estate investors are inclined to will result in increased interest in investment areas and, consequently, an increase in the property’s value. Real estate owners and real estate agents, knowing the investors’ inclinations, can use this to their advantage in the process of searching for the best offer [

81]. Referring to the topic of this study, the essence of human behavior in the process of investing in risky areas is not the stress associated with the initiation of possible threats, but the desire to profit, multiply assets, and obtain the highest possible income from the property.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K. and N.C.-G.; methodology, D.K. and N.C.-G.; software, D.K.; validation, D.K., N.C.-G. and M.N.; formal analysis, D.K., N.C.-G. and M.N.; investigation, D.K. and N.C.-G.; resources, D.K. and N.C.-G.; data curation, D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K., N.C.-G. and M.N.; writing—review and editing, D.K., N.C.-G. and M.N.; visualization, D.K.; supervision, N.C.-G.; project administration, D.K., N.C.-G. and M.N.; funding acquisition, N.C.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The research analysis included in the publication was carried out as part of D. Kloskowski’s research internship at University of Zielona Gora in Zielona Gora.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kloskowski, D. The Coastal Market in the Light of Flood Threats. Scientific Papers of the University of Szczecin. Studies and Papers of the Faculty of Economic Sciences and Management. In 26 Quantitative Methods in Economics; WNEIZ: Toruń, Poland, 2012; pp. 179–192. Available online: http://www.wneiz.univ.szczecin.pl/nauka_wneiz/sip/sip26-2012/SiP-26-179.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Act of 27 March 2003 on Spatial Planning and Development Art. 4, Section 1a. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20240001130/U/D20241130Lj.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Act of 21 March 1991 on Maritime Areas of the Republic of Poland and Maritime Administration (Journal of Laws of 2024, Item 1125), Art. 37a, Section 1. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20240001125/U/D20241125Lj.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Chrabąszcz, K. Condo Investments as an Alternative Form of Capital Allocation. Sci. Pap. Małopolska Univ. Econ. Tarnów 2014, 24, 47–58. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/713564831/Condoinwestycje-jako-alternatywna-forma-alokacji-kapitału (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Castro Noblejas, H.; Vías Martínez, J.; Mérida Rodríguez, M.F. The relationship between views and property applications for the Mediterranean coast. ISPRS Int. J. Geogr. Inf. 2022, 11, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifam Marthya, K.; Major, M.D. Real estate market trends in the first new urban city: Seaside, Florida. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Sustain. Urban Dev. 2022, 17, 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutkowski, M. The Social and Economic Importance of Resources and Assets of the Polish Coastal Zone. In Seashore and Sustainability; Furmańczyk, K., Ed.; University of Szczecin Publishing House, Institute of Marine Sciences: Szczecin, Poland, 2006; pp. 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cykalewicz, T. Specificity of Spatial Planning of Coastal Areas. In Seashore and Sustainability; Furmańczyk, K., Ed.; University of Szczecin Publishing House, Institute of Marine Sciences: Szczecin, Poland, 2006; p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Panasiuk, A. Economics of Tourism; PWN Scientific Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 2006; pp. 110–111. [Google Scholar]

- Domański, R. Principles of Socio-Economic Geography; PWN Scientific Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 1993; pp. 153–154. [Google Scholar]

- Benko, G. Geografia Technopolii; PWN Scientific Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 1993; pp. 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Parteka, T.; Zaucha, J. Creating the Development Zone of the South Baltic Sea; Matczak, R., Ed.; Baltic Regional Studies Publishing House: Olsztyn, Poland, 2004; pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tyndall, J. Sea level rise and home prices: Evidence from Long Island. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2023, 67, 579–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, J.; Devaney, S.; Sayce, S.; Van de Wetering, J. Climate risk and real estate prices: What do we know? J. Portf. Manag. 2021, 47, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, R. Smooth Interpolation of Scattered Data by Local Thin Plate Splines. Comput. Math. Appl. 1982, 8, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musielak, S.; Furmańczyk, K.; Osadczuk, K.; Prajs, J. Photointerpretative Atlas of the Dynamics of the Coastal Zone, 1958–1989, Świnoujście-Pogorzelica Section. Scale 1:5000. 21 Sections; Musielak, S., Ed.; Institute of Marine Sciences: Szczecin, Poland; Publishing House of the Maritime Office in Szczecin: Szczecin, Poland, 1991; OPGK Szczecin. [Google Scholar]

- Rotnicki, K. Threats to the Polish Baltic Coastal Zone by Accelerated Sea-Level Rise and the Problem of Coastal Zone Management/Les Menaces Liées à L’élévation Rapide du Niveau de la Mer Sur le Littoral Polonais et le Problème de la Gestion de la Zone Côtière. Littoral 95 1997, 47–48, 455–462. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/canan_0755-9232_1997_num_47_1_1754 (accessed on 11 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Subotowicz, W. Lithodynamics of Cliff Shores on the Polish Coast; Ossoliński National Institute: Wrocław, Poland, 1982; p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- Subotowicz, W. Transformation of the Cliff Coast in Poland. J. Coast. Res. 1995, 22, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zeidler, R.B. Climate change vulnerability and response strategies for coastal areas of Poland. Clim. Change 1997, 36, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitinas, A.; Žaromskis, R.; Gulbinskas, S.; Damušyte, A.; Žilinskas, G.; Jarmalavičius, D. The Results of Integrated Investigations of the Lithuanian Coast of Baltic Sea, Geology, Geomorphology, Dynamics and Human Impact. Geol. Q. 2005, 49, 355–362. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H. The Evolution of the Baltic Sea—Changing Shorelines and Unique Coasts. Spec. Pap.-Geol. Surv. Finl. 2006, 41, 1721. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292922698_The_evolution_of_the_Baltic_Sea_-_Changing_shorelines_and_unique_coasts (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Hoffmann, G.; Lampe, R. Sediment budget calculation to estimate Holocene coastal changes on the southwest Baltic Sea (Germany). Mar. Geol. 2007, 243, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdmann, A.; Käärd, A.; Kelpsaite, L.; Kurennoy, D.; Soomere, T. Marine Coastal Hazards for the Eastern Coasts of the Baltic Sea. Baltica 2008, 21, 3–12. Available online: https://baltica.gamtc.lt/administravimas/uploads/2008_vol21(1-2)-01_5e6b2f5f7b026.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Zhang, W.; Harff, J.; Schneider, R.; Wu, C. Development of a modeling methodology for simulating long-term morphological evolution of the southern Baltic coast. Ocean. Dyn. 2010, 60, 1085–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Harff, J.; Schneider, R.; Meyer, M.; Wu, C. A multiscale centennial morphodynamic model for the Southern Baltic coast. J. Coast. Res. 2011, 27, 890–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagdanavičiute, I.; Kelpšaite, L.; Daunys, D. Assessment of shoreline changes along the Lithuanian Baltic Sea coast during the period 1947–2010. Baltica 2012, 25, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzka, E. Development Trends of the Polish Coasts of the Southern Baltic; Gdańsk Scientific Society: Gdańsk, Poland, 1999; p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- Zawadzka, E. Morphodynamics of the Southern Baltic Dune Coasts; University of Gdańsk Publishing House: Gdańsk, Poland, 2012; p. 353. [Google Scholar]

- Jarmalavičius, D.; Žilinskas, G.; Pupienis, D. Observation on the interplay of sea level rise and the coastal dynamics of the Curonian Spit, Lithuania. Geologija 2013, 55, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kolander, R.; Morche, D.; Bimbose, M. Quantification of moraine cliff erosion on Wolin Island (Baltic Sea, northwest Poland). Baltica 2013, 26, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilcewicz-Stefaniuk, D.; Czerwiński, T.; Koryczan, A.; Targosz, P.; Stefaniuk, M. Landslides Survey in the Northeastern Poland. Pol. Geol. Inst. Spec. Pap. 2005, 20, 67–73. Available online: https://reference-global.com/article/10.2478/logos-2014-0018?tab=references (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Carpenter, N.E.; Dickson, M.E.; Walkden, M.J.A.; Nicholls, R.J.; Powrie, W. Effects of varied lithology on soft-cliff recession rates. Mar. Geol. 2013, 354, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uścinowicz, S.; Zachowicz, J.; Graniczny, M.; Dobracki, R. Geological Structure of the Southern Baltic Coast and Related Hazards. Pol. Geol. Inst. Spec. Pap. 2004, 15, 61–68. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297456985_Geological_structure_of_the_southern_Baltic_Coast_and_related_hazards (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Uścinowicz, G.; Kramarska, R.; Kaulbarsz, D.; Jurys, L.; Frydel, J.; Przezdziecki, P.; Jegliński, W. Baltic Sea coastal erosion; a case study from the Jastrzębia Góra region. Geologos 2014, 20, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suursaar, U.; Jaagus, J.; Kullas, T. Past and Future Changes in Sea Level Near the Estonian Coast in Relation to Changes in Wind Climate. Boreal Environ. Res. 2006, 11, 123–142. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229051992_Past_and_future_changes_in_sea_level_near_the_Estonian_coast_in_relation_to_changes_in_wind_climate (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Weisse, R.; Bellafiore, D.; Menéndez, M.; Méndez, F.; Nicholls, R.J.; Umgiesser, G.; Willems, P. Changing extreme sea levels along European coasts. Coast. Eng. 2014, 87, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HELCOM. Climate Change in the Baltic Sea Area—HELCOM Thematic Assessment in 2007. Baltic Sea Environ. Proc. 2007, 111, 49. Available online: https://www.baltex-research.eu/BACC/material/Climate_change_report_07.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- HELCOM. Climate Change in the Baltic Sea Area—HELCOM Thematic Assessment in 2013. Baltic Sea Environ. Proc. 2013, 137, 66. Available online: https://helcom.fi/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/BSEP137.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Furmańczyk, K. Present coastal zone development of the tide less sea in light of the South Baltic Sea coast remote sensing investigating. Univ. Szczec. Diss. Stud. 1994, 179, CCXXXV. [Google Scholar]

- Furmańczyk, K.; Musielak, S. Circulation systems of the coastal zone and their role in south Baltic morphodynamic of the coast, Circulation systems of the coastal zone and their role in the South Baltic morphodynamics of the coast. Quart. Stud. Pol. Spec. Issue 1999, 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Uścinowicz, G.; Uścinowicz, S.; Szarafin, T.; Maszloch, E.; Wirkus, K. Rapid coastal erosion, its dynamics and cause—An erosional hot spot on the southern Baltic Sea coast. Oceanology 2024, 66, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musielak, S.; Furmańczyk, K.; Bugajny, N. Factors and processes forming the Polish Southern Baltic sea coast on various temporal and spatial scale. COASTALRL 2017, 19, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzka-Kahlau, E. Trends in southern Baltic coast development during the last hundred years. Peribalticum 1999, 7, 115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, H.E.M.; Kniebusch, M.; Dieterich, C.; Gröger, M.; Zorita, E.; Elmgren, R.; Myrberg, K.; Ahola, M.P.; Bartosova, A.; Bons-Dorff, E.; et al. Climate change in the Baltic Sea region: A summary. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2022, 13, 457–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michałowska, K.; Głowienka, E. Multi-temporal analysis of changes of the southern part of the Baltic Sea coast using aerial remote sensing data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.; Habib, M.; Beckmann, S. Best Estimates for Historical Storm Surge Water Level and MSL Development at the Travemünde/Baltic Sea Gauge Over the Last 1000 Years. In Die Küste; Bundesanstalt für Wasserbau: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2022; p. 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemmensen, L.B.; Bendixen, M.; Nielsen, L.; Jensen, S.; Schrøder, L. Evolution of the cuspate foothill coast (Flakket, Anholt, Dania) in the years 2006–2010. Bull. Geol. Soc. Den. 2011, 59, 37–44. Available online: www.2dgf.dk/publikationer/bulletin (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Wierzejewski, K. Information on the Results of Coastal Protection Inspections; Publishing House of the Supreme Audit Office—Department of Communication and Transport Systems: Warsaw, Poland, 2004; p. 15. Available online: http://www.nik.gov.pl/kontrole/wyniki-kontroli-nik/kontrola,1454.html (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Ghanbari, M. Compound Coastal-Riverine Flooding Hazard Along the U.S. Coasts. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2021EF002055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, M.; Farfán, J.F.; Willems, P.; Cea, L. Assessing the Effects of Climate Change on Compound Flooding in Coastal River, Areas. Water Resour. 2021, 57, e2020WR029321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogston, A.S.; Cacchione, D.A.; Sternberg, R.W.; Kineke, G.C. Observations of storm and river flood-driven sediment transport on the northern California continental shelf. Cont. Shelf Res. 2000, 20, 2141–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrawski, R.; Zawadzka-Kahlau, E. The Future of the Protection of Polish Sea Coasts; Scientific Publishing House of the Maritime Institute in Gdańsk: Gdańsk, Poland, 2006; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Pruszak, Z. Vulnerability and Adaptation of Polish Coast to Impact of Sea-Level Rise (SLR). Arch. Hydro-Eng. Environ. Mech. 2001, 48, 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Pruszak, Z. Sea Water bodies. Outline of Physical Processes and Environmental Engineering; Polish Academy of Sciences Publishing House: Gdańsk, Poland, 2003; pp. 1–272. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesel, J.; Wolff, C.; Lorenz, M. Brief Communication: From modeling to reality—Insights from a recent severe storm surge event along the German Baltic Sea coast. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2024, 24, 3841–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuźmiński, W.; Kloskowski, D. The Use of Geostatistical Methods in the Analysis of Changes in the Erosion-Accumulation Systems of the Southern Baltic Sea. Dissertations and Studies/University of Szczecin. (831 Quantitative Methods on the Real estate and Labor Markets). 2012, pp. 69–81. Available online: www.baltex-research.eu/SZC2009/index.html (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Olczyk, W. Protection of the Seashore from Excessive Human Interference; Department of Infrastructure of the Supreme Audit Office: Warsaw, Poland, 2020; Available online: https://cejsh.icm.edu.pl/cejsh/element/bwmeta1.element.desklight-00f156b8-44ff-4cf7-80e1-163c48d0634f/c/94-107.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Pruszak, Z.; Zawadzka, E. Vulnerability of Poland’s Coast to Sea-Level Rise. Costal Eng. J. 2005, 47, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasby, G.P. Disposal of chemical weapons in the Baltic Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 1997, 206, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobloch, T. Chemical Munitions Dumped in the Baltic Sea: Report of the Ad Hoc Expert Group to Update and Review the Existing Information on Dumped Chemical Munitions in the Baltic Sea, (HELCOM MUNI), Helsinki Commission, Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission. 2014. Available online: https://helcom.fi/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Dumped-chemical-munitions-in-the-Baltic-Sea.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Bełdowski, J.; Szubska, M.; Emelyanov, E.; Garnaga, G.; Drzewińska, A.; Bełdowska, M.; Vanninen, P.; Ostin, A.; Fabisiak, J. Arsenic concentrations in Baltic Sea sediments near chemical munitions dumps. Themat. Stud. Oceanogr. 2015, 128, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemikoski, H.; Straumer, K.; Ahvo, A.; Turja, R.; Brenner, M.; Rautanen, T.; Lang, T.; Lehtonen, T.K.; Vanninen, P. Detection of chemical warfare agent related phenylarsenic compounds and multibiomarker responses in cod (Gadus morhua) from munition dumpsites. Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 162, 105160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area, Done in Helsinki on 9 April 1992. 1992. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.Nsf/download.xsp/WDU20000280346/T/D20000346L.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Lang, T.; Kotwicki, L.; Czub, M.; Grzelak, K.; Weirup, L.; Straumer, K. Health Status of Fish and Benthos Communities at Chemical Munitions Dumps in the Baltic Sea. In Towards Monitoring the Hazard of Dumped Munitions (MODUM); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, L.; Ytreberg, E.; Jukka-Pekka, J.; Fridell, E.; Eriksson, M.; Lagerström, M.; Maljutenko, I.; Raudsepp, U.; Fischer, V.; Roth, E. Recreational boating and emissions model—Implementation for the Baltic Sea. Ocean Sci. 2020, 16, 1143–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, K.; Jalkanen, J.-P.; Johansson, L.; Smailys, V.; Telemo, P.; Winnes, H. Risk assessment of bilge water discharges in two Baltic shipping lanes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 126, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graca, B.; Szewc, K.; Zakrzewska, D.; Dołęga, A.; Szczebrowska-Boruchowska, M. Sources and fate of microplastics in marine and beach sediments of the Southern Baltic Sea—A preliminary study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 7650–7661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Act of 13 November 2003 on the Income of Local Government Units (Dz. U. z 2022 r. poz. 2267). Available online: https://dziennikustaw.gov.pl/DU/2022/2267 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Boland, B.; Levy, C.; Palter, R.; Stephens, D. Climate Risk and Opportunity for Real Estate; McKinsey & Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 2022; pp. 1–8. Available online: www.mckinsey.com/industries/real-estate/our-insights/climate-risk-and-the-opportunity-for-real-estate (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Chong, J.; Phillips, G.M. COVID-19 losses in the real estate market: Capital analysis. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 45, 102131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzka, E. Determination of the State of the Erosion-Accumulation System of Sea Coasts and Forecasts of Their Development, Work Carried out Within the Framework of the Targeted Project Entitled Strategy for the Protection of Sea Coasts; Publishing House of the Maritime Institute in Gdańsk: Gdańsk, Poland, 1999; pp. 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Safarli, C.; Kolach, S.; Zhyvko, M.; Volskyi, O.; Bobro, N. Considering Globalisation Risks in the Formation and Implementation of International Investment Strategies. Pak. J. Nat. Soc. Sci. 2024, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoc, N.M.; Tien, N.H.; Hieu, V.M. The importance of factors influencing investment decisions in the real estate market in the post-pandemic period. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2023, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska-Stasiak, E.; Sopiński, M.; Wiśniewska, E.; Wójtowicz-Korycka, J.; Załęczna, M. Conditions of Real Estate Market Development; PS ABSOLWENT Publishing House: Łódź, Poland, 2000; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Wiśniewski, R.; Brzezicka, J. The global real estate market: Data from European countries. J. Eur. Real Estate Res. 2021, 14, 120–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatarkiewicz, W. History of Philosophy; State Scientific Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 1991; Volume III, p. 318. [Google Scholar]

- Scala, P.; Toimil, A.; Álvarez-Cuesta, M.; Manno, G.; Ciraolo, G. Mapping decadal land cover dynamics in Sicily’s coastal regions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbard, S.; Caldeira, K.; Bala, G.; Phillips, T.J.; Wickett, M. Climate effects of global land cover change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, 2005GL024550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, A.; Koley, B.; Choudhury, T.; Saraswati, S.; Ray, B.C.; Um, J.S.; Sharma, A. Assessing coastal land-use and land-cover change dynamics using geospatial techniques. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hozer, J. Miscellanea Mikroeconometrii; Institute of Economic Analysis, Diagnostics and Forecasts in Szczecin: Szczecin, Poland, 2010; p. 153. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).