Fracture Prediction Based on a Complex Lithology Fracture Facies Model: A Case Study from the Linxing Area, Ordos Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

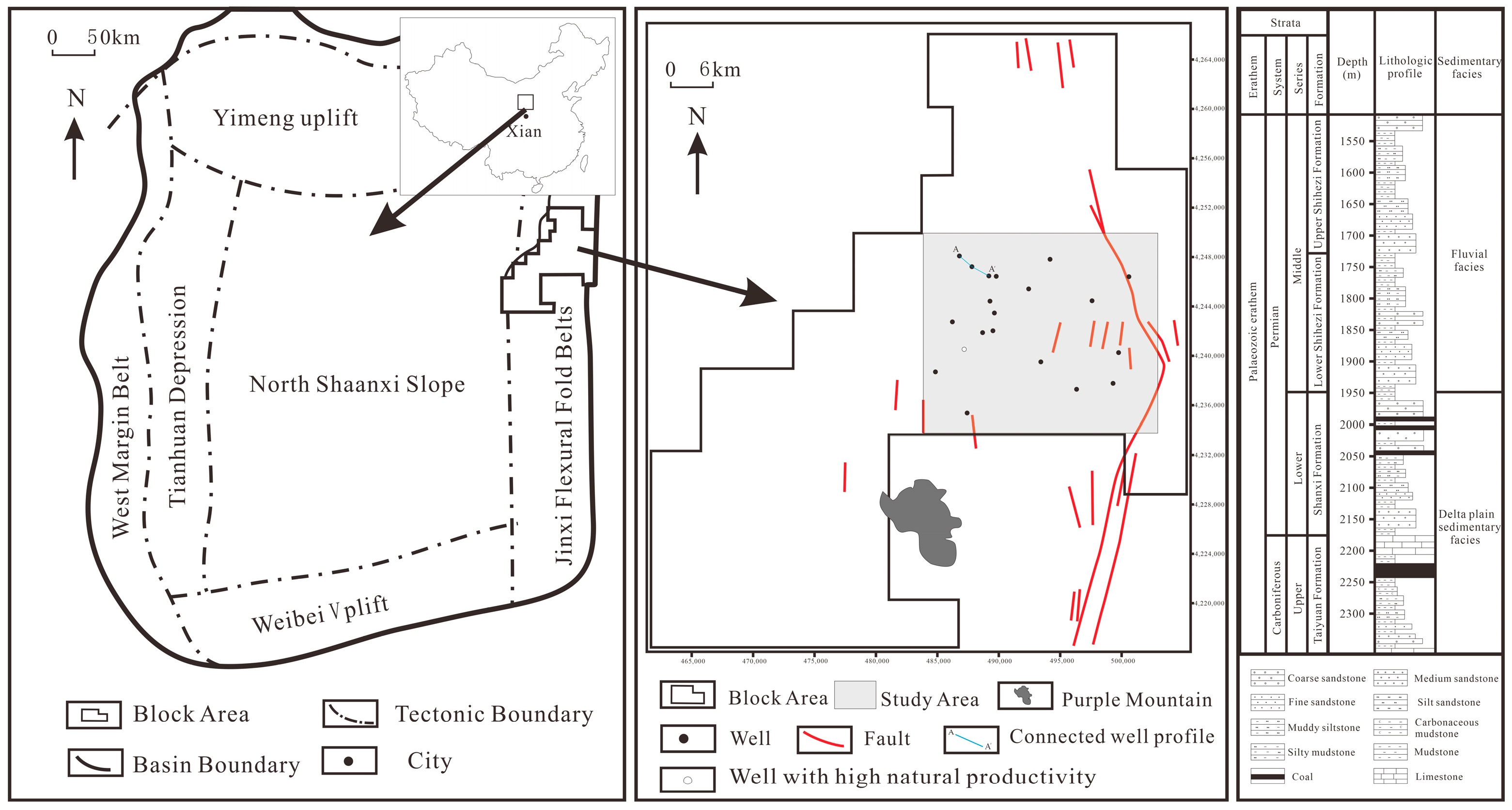

2. Study Area and Data

2.1. Study Area

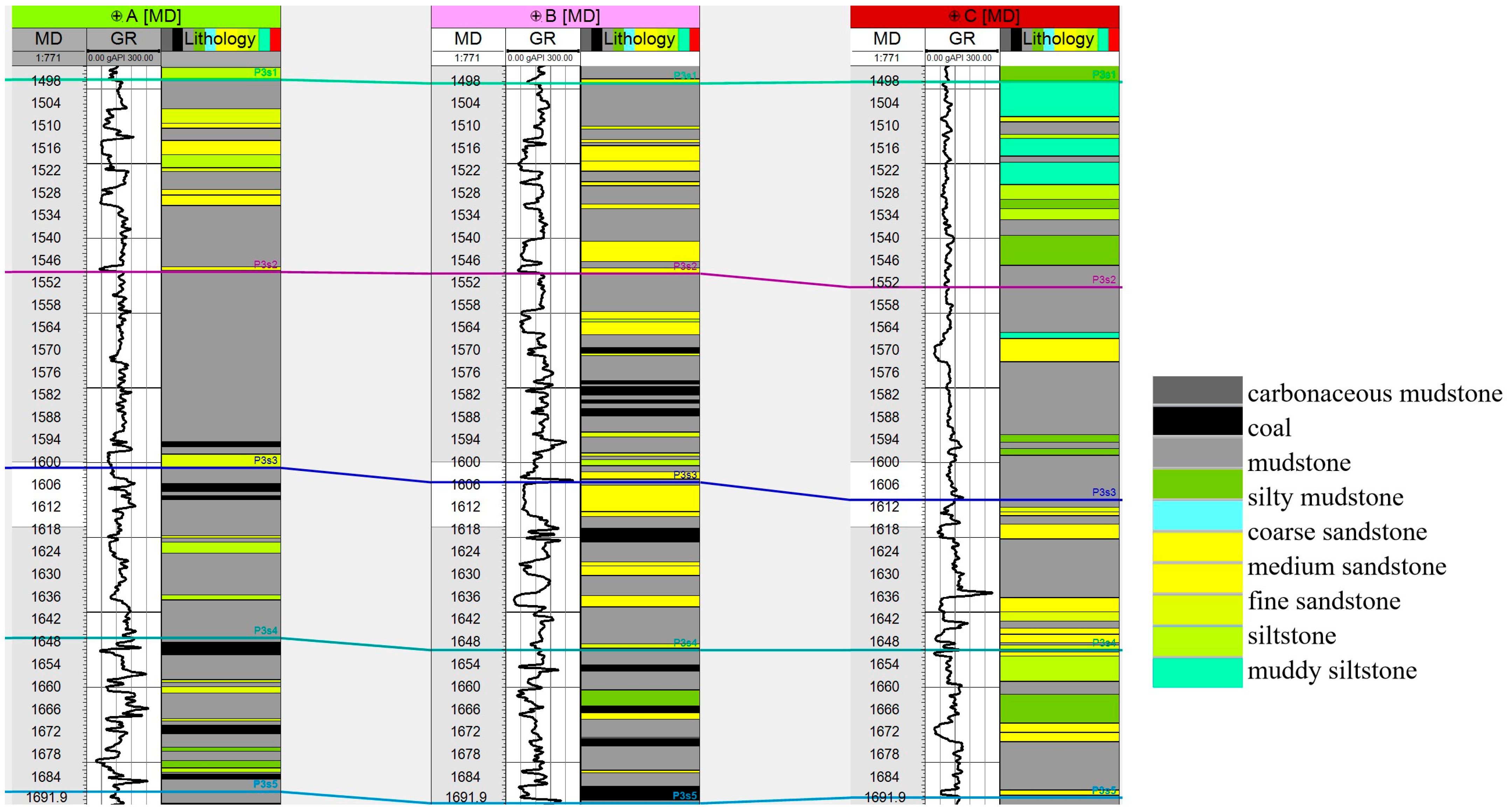

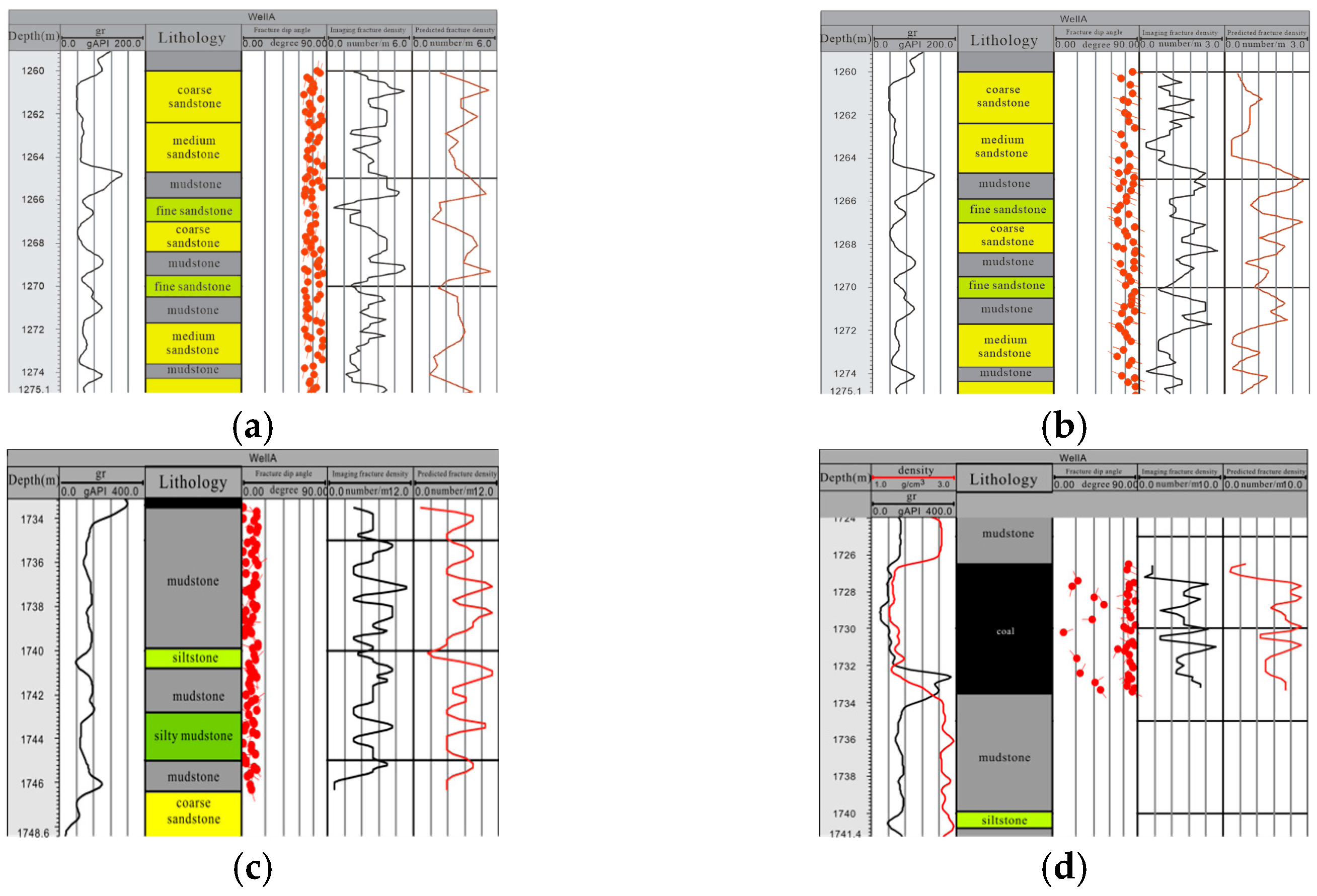

2.2. Data and Method

- (i)

- By comparing core samples with well logs, we analyzed the image log characteristics of nine lithologies and created a lithology identification template. Applying this template to the 1790 m of image log data from the study area allowed us to identify all nine lithology types.

- (ii)

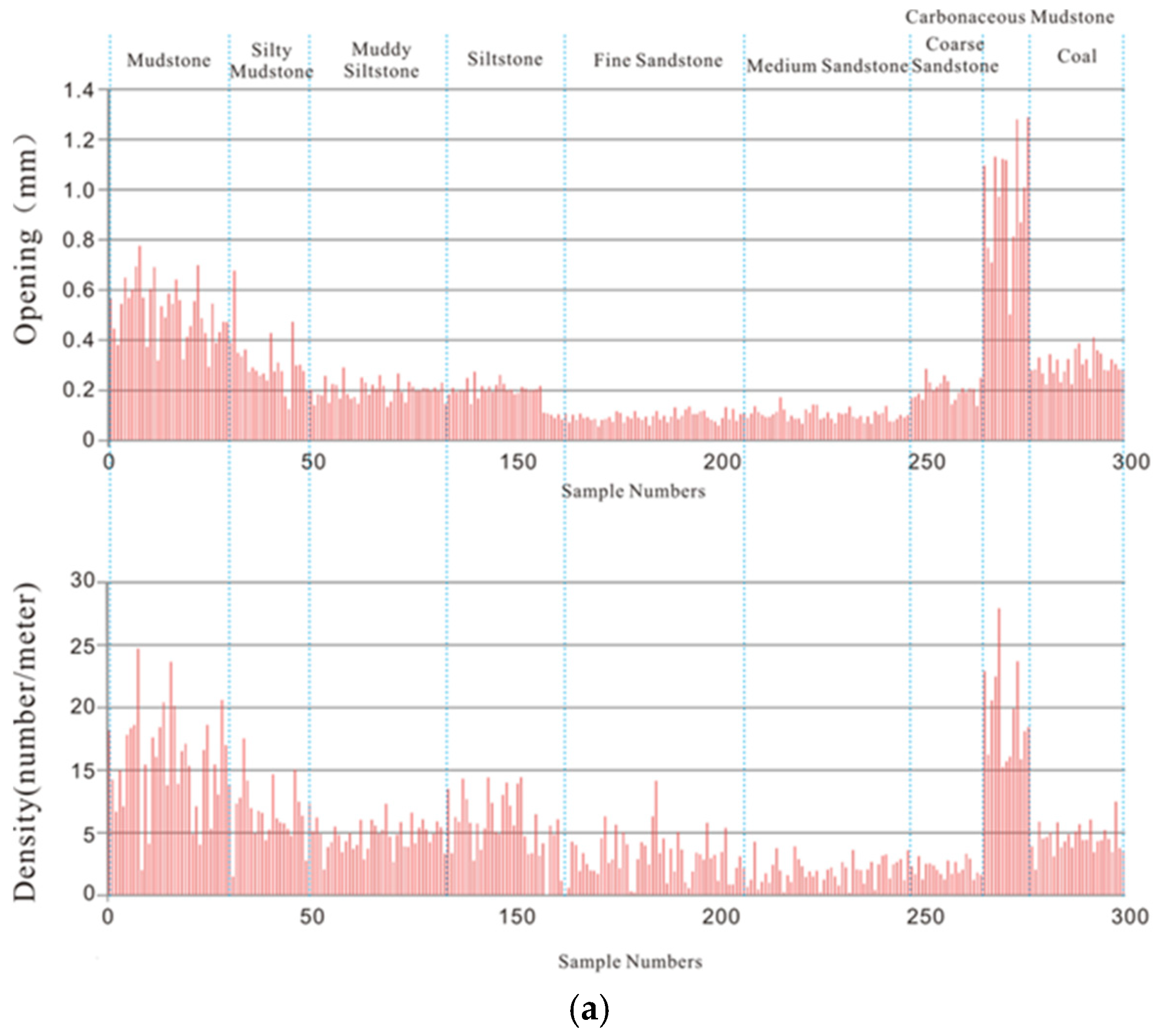

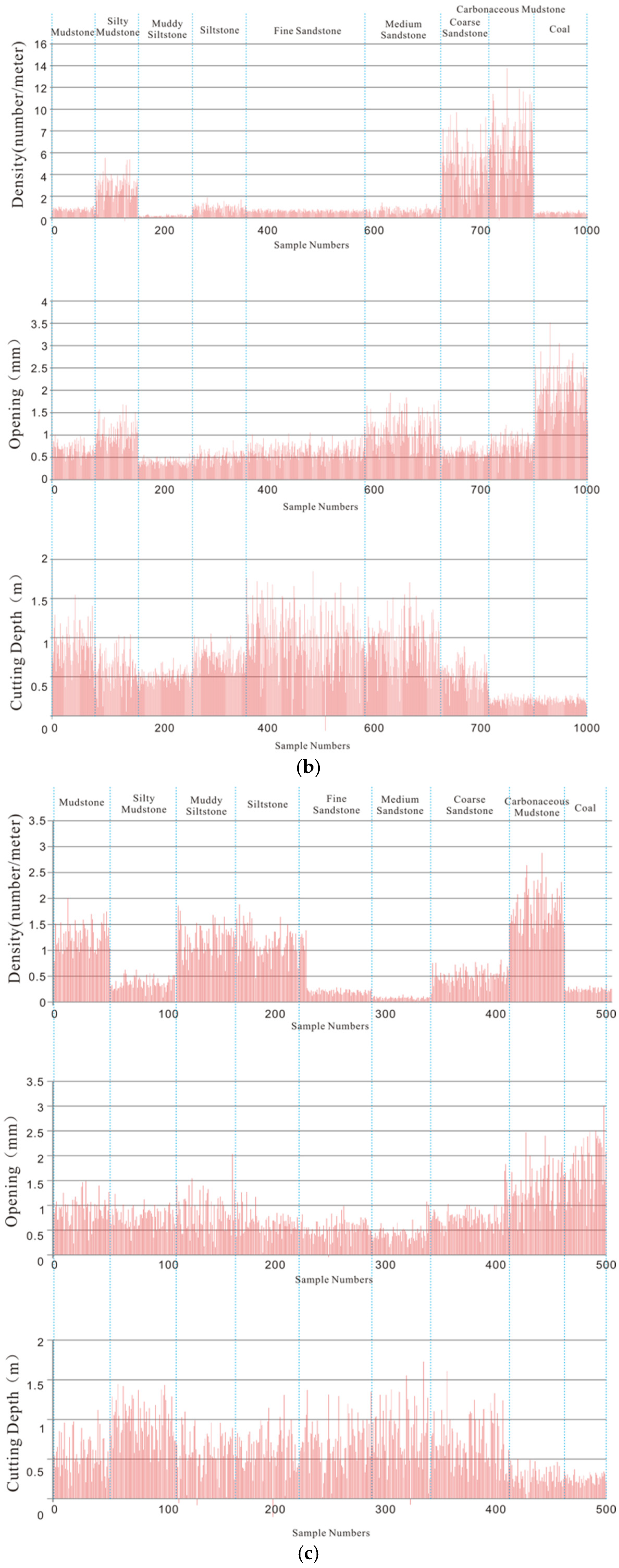

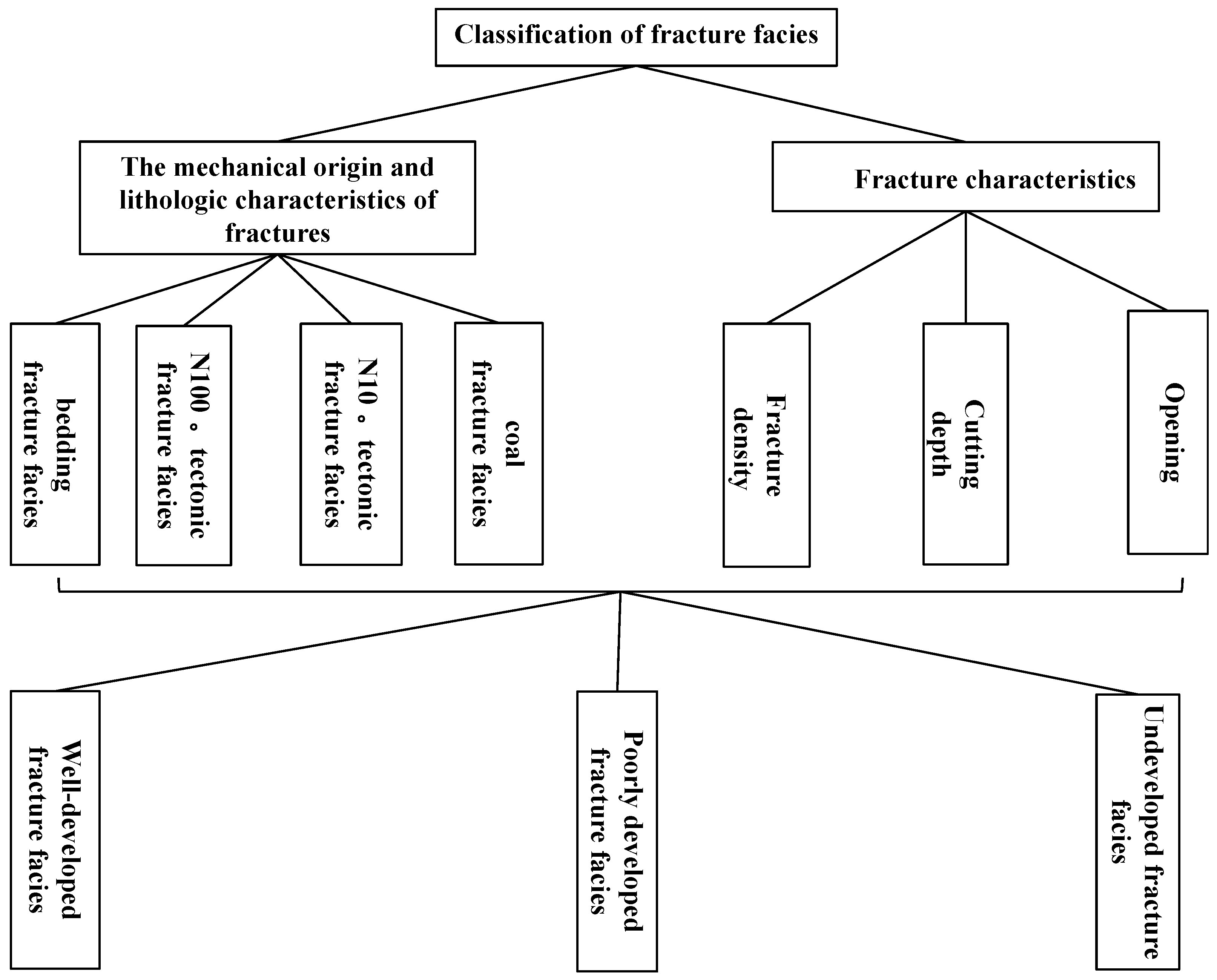

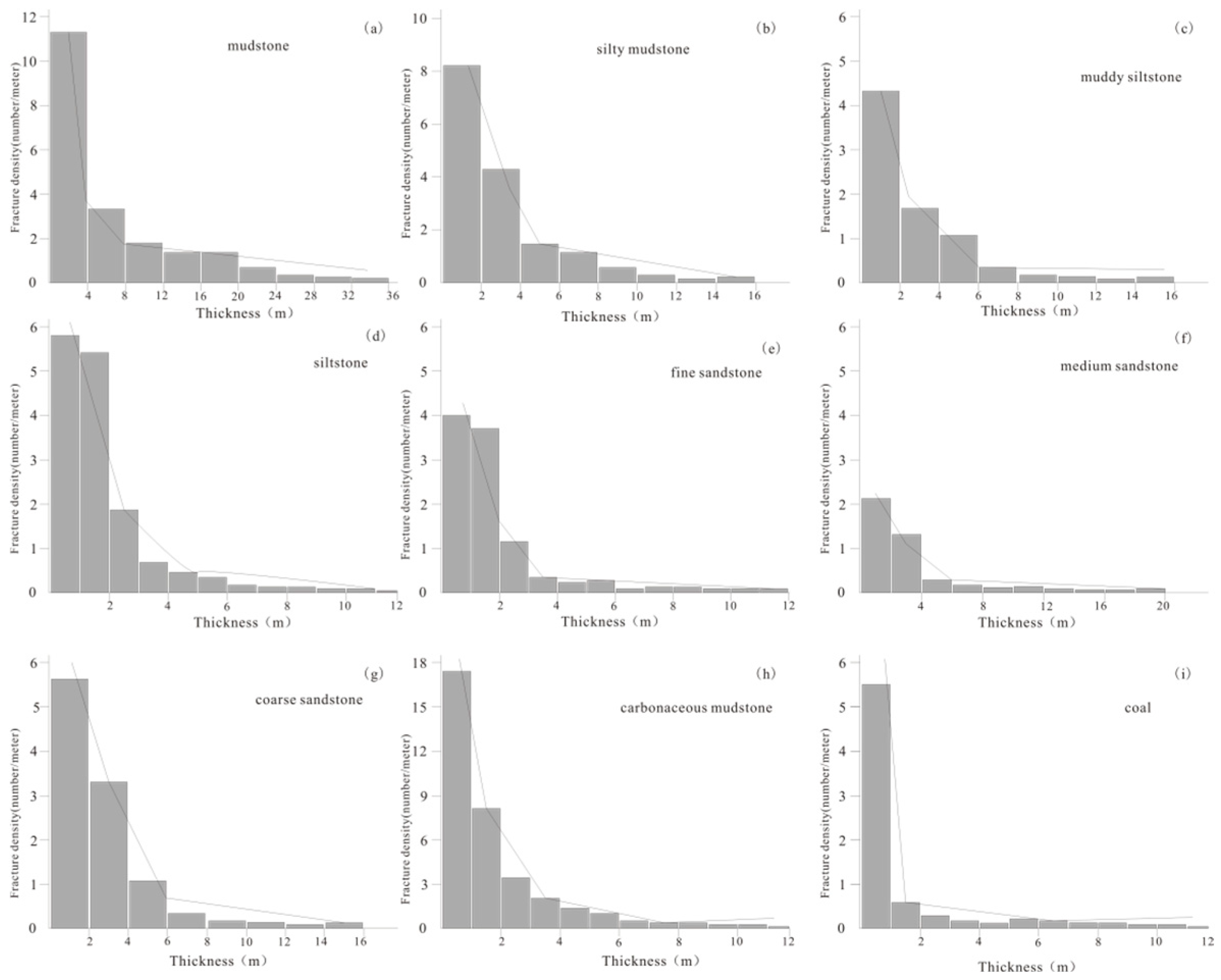

- By identifying fractures on imaging logging and combining with the nine types of lithologies in (i), we can obtain the fracture parameters of different lithologies, such as fracture occurrence, density and so on (Table 1). Through comprehensive analysis and classification of these parameters, four fracture-phase classification schemes reflecting the causes and development characteristics of fractures are obtained.

- (iii)

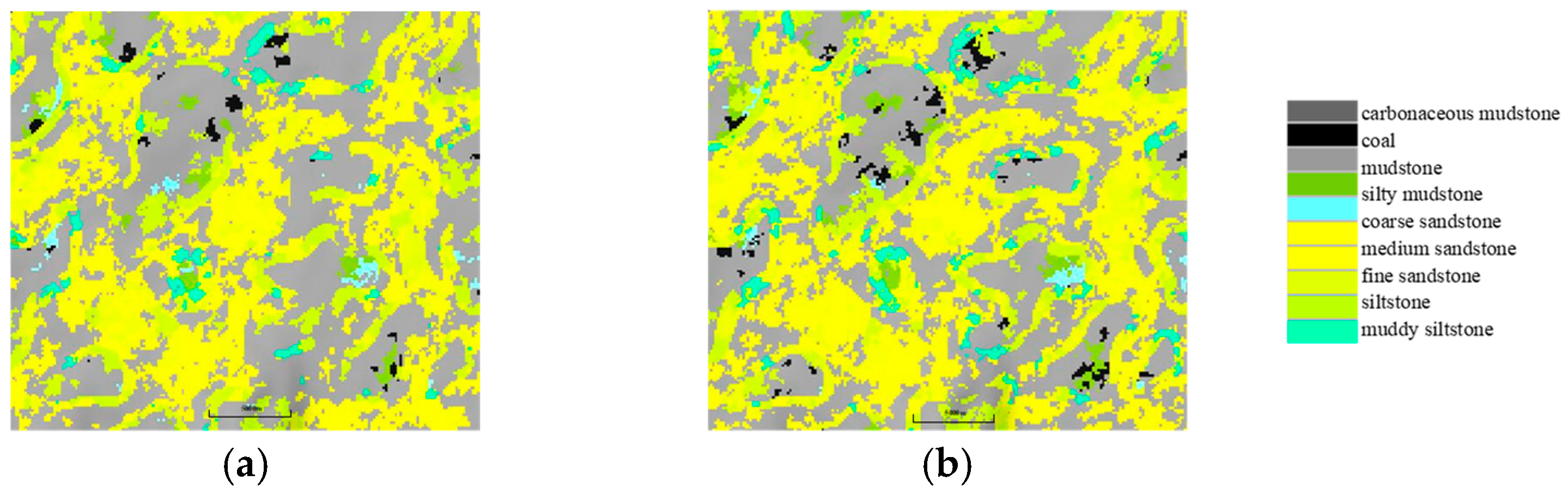

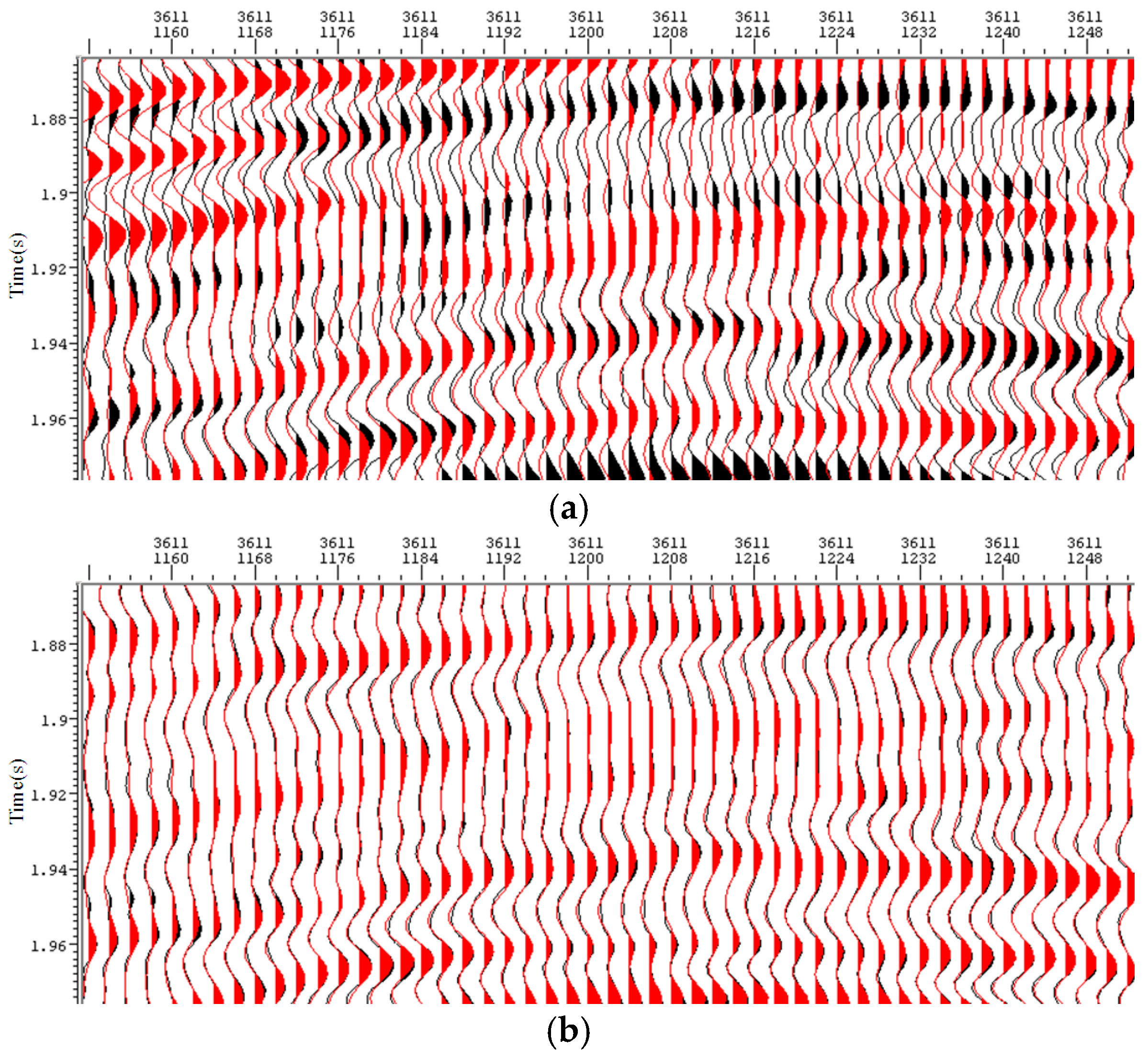

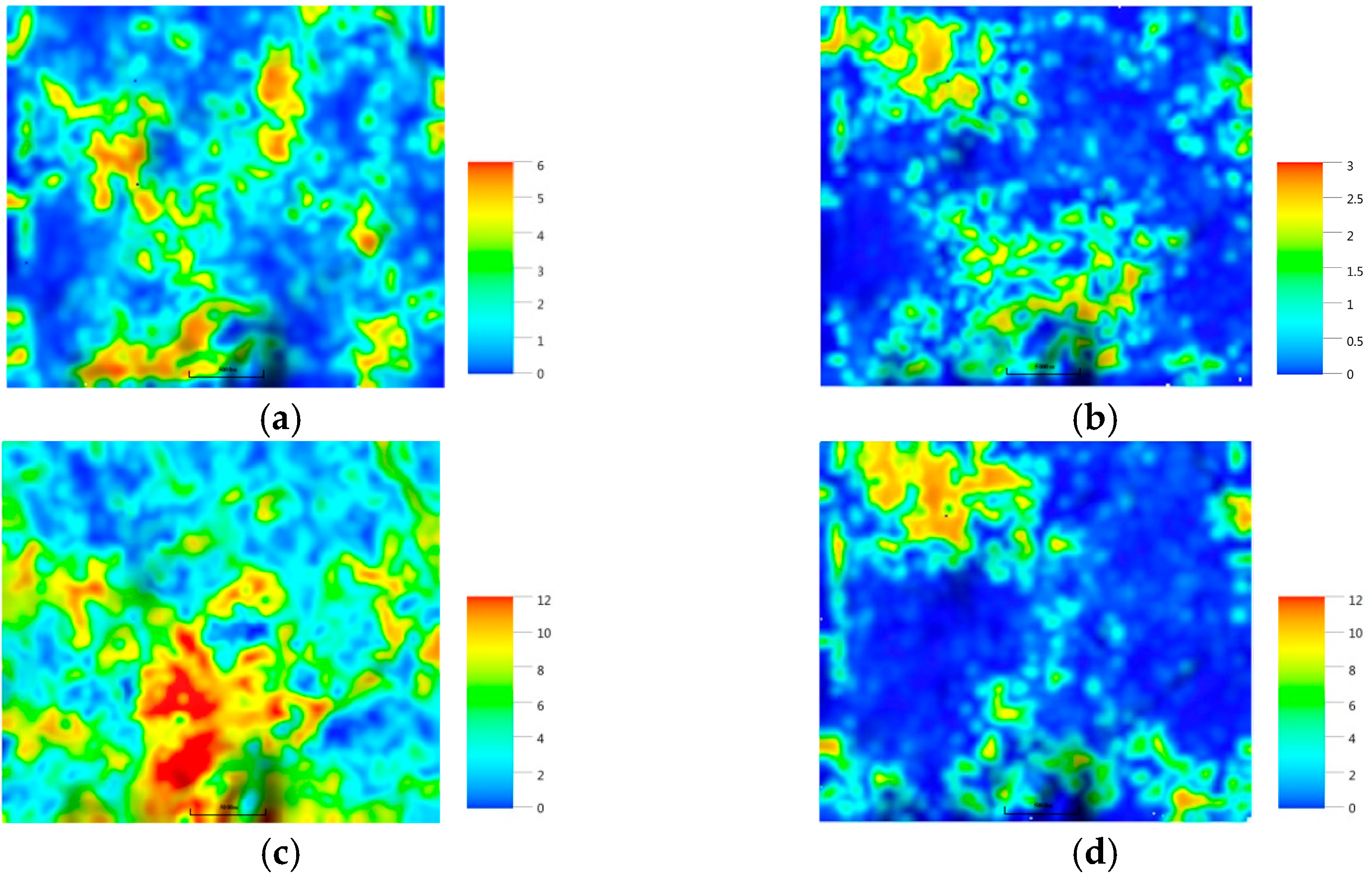

- We sought to establish a geological model containing nine lithologies and transform the 3D lithologic model into the 3D model of fracture facies by the classification of fracture facies. At the same time, the fracture density parameters of different fracture facies can be obtained by a seismic multi-parameter neural network algorithm. Finally, a three-dimensional fracture distribution model can be obtained. The model can reflect the fracture density and parameter characteristics of different fracture facies in 3D space.

3. Establishment of an Imaging—Lithology Identification Template

- (1)

- Mudstone: Mudstone is usually formed in a static water environment. The horizontal bedding is well-developed, the resistivity is generally low, and the GR values are generally high. The horizontal bedding in the image shows better layering and has good correspondence with the core.

- (2)

- Muddy siltstone and silty mudstone: These two lithologies are composed of silt and clay in different proportions and their sedimentary environment and sediment particle sizes are similar; therefore, effectively identifying them based on the core alone is difficult. However, the differences in clay minerals in the image logs are easier to identify. For example, silty mudstone contains more mud, and dark bands are more common than bright bands. Alternatively, muddy siltstone contains more sand, and bright bands are slightly more common than dark bands. Because the depositional environments of the two lithologies are similar, with both deposited in water with low energy, the main sedimentary structure that develops is horizontal bedding. Therefore, layered stripes are common throughout the image logs. The GR value of muddy siltstone is slightly lower than that of silty mudstone; thus, these two lithologies can be further distinguished by the GR values on conventional logs.

- (3)

- Sandstone (siltstone, fine sandstone, medium sandstone and coarse sandstone): The GR values of these four lithologies decrease in sequence, and spots of different colors are observed on the image logs. Because the particle sizes increase from fine to coarse, the colors of the spots change from dark to bright, with coarse sandstone the brightest and siltstone the darkest. Sandstones of different particle sizes are more easily distinguished via their color characteristics. Finer rock particles, including fine sandstone, tend to form abundant horizontal bedding, while coarse sandstone typically forms cross-bedding.

- (4)

- Carbonaceous mudstone: the organic carbon content of carbonaceous mudstone is generally 10–30%, and the organic carbon content in coal-bearing strata is between that of mudstone and coal. The GR value is higher than that of mudstone, and the density is lower than that of mudstone. Because of the carbon content, a large number of black spots can be found on the image logs. These spots are obvious, and the resistivity is low.

- (5)

- Coal: Coal occurs in the Shanxi Formation and Taiyuan Formation. The values of GR, density, interval transit time, neutron, and resistivity are obviously low; therefore, coal is easy to identify using conventional logs. The resistivity of coal in this area is mainly high, and it is displayed as obvious bright white bands on the image logs and is significantly different from surrounding rocks with dark horizontal bedding. A thin, dark massive interlayer and fractures are all developed.

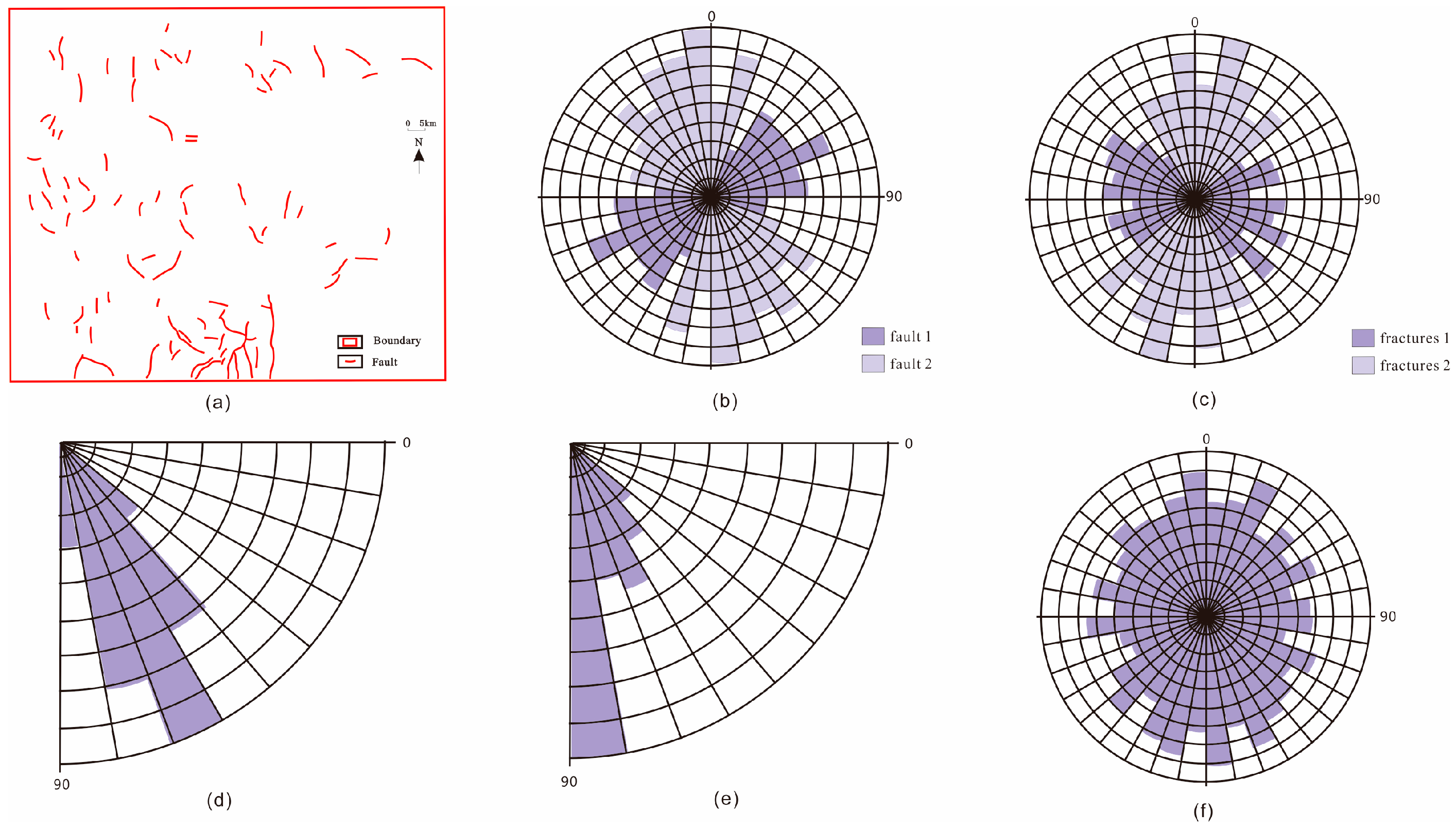

4. Fracture Identification and Fracture Facies Classification

4.1. Identification of Fractures

4.2. Classification of Fracture Facies

5. Predictive Model of Fracture Facies

5.1. Establishing a Fracture Facies Prediction Model Combined with a Geological Model

5.2. Multiattribute Comprehensive Prediction of Fracture Density

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Core observations and conventional logging analyses of the abundant image logs of the study area were conducted to describe the morphology, color, geophysical features and geological characteristics to establish imaging identification templates for the 9 observed lithologies. These templates provide data that are deficient in conventional logging and reflect the geological characteristics of the different lithologies, such as their bedding and particle size. Ultimately, the results improved the identification accuracy of the complex lithologies and provided a foundation for future research of fracture facies.

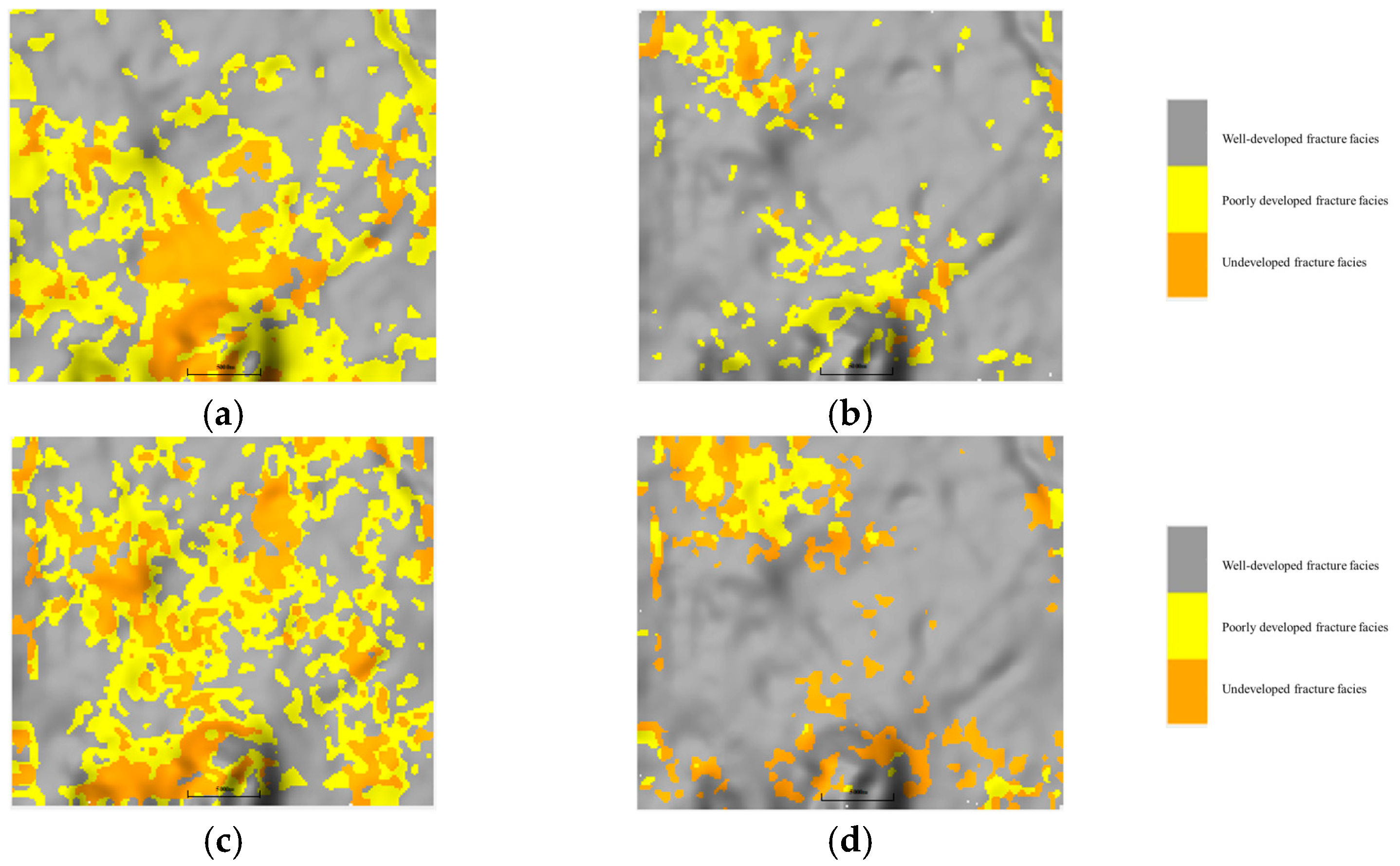

- (2)

- Fractures were identified by integrating characteristics observed from both image logs and core samples. The genetic types, occurrence, opening, cutting depth, lithology and density of the fractures were considered in the fracture facies research. The fractures in the study area were divided into 4 facies types: bedding fracture facies, N100° tectonic fracture facies, N10° tectonic fracture facies and coal fracture facies. The different genetic fractures were further divided into the following three types according to the degree of fracture development: well-developed fracture facies, poorly developed fracture facies and undeveloped fracture facies.

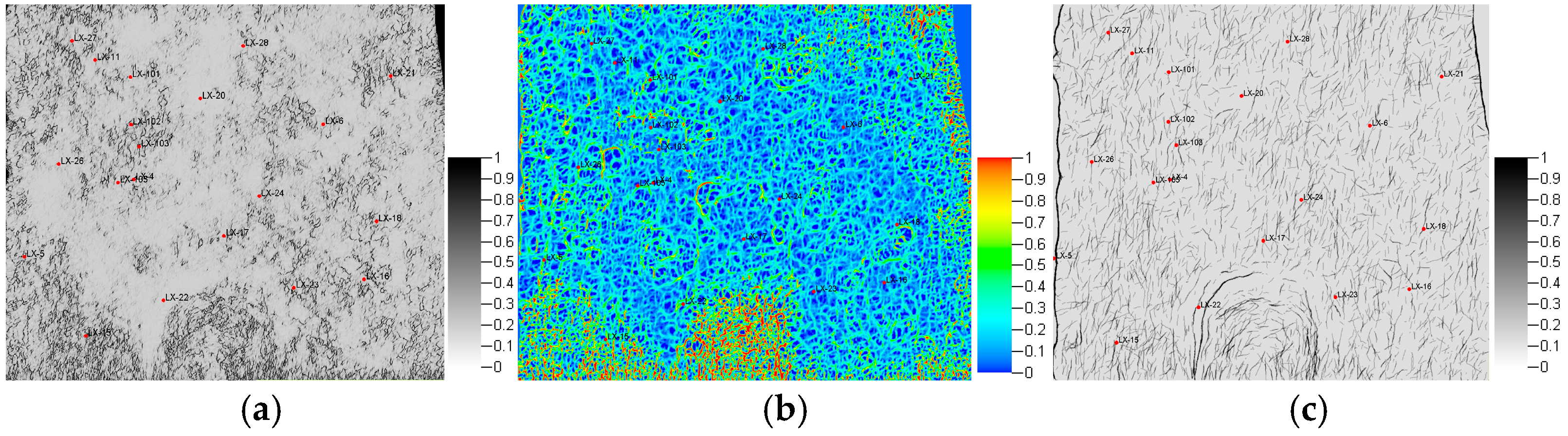

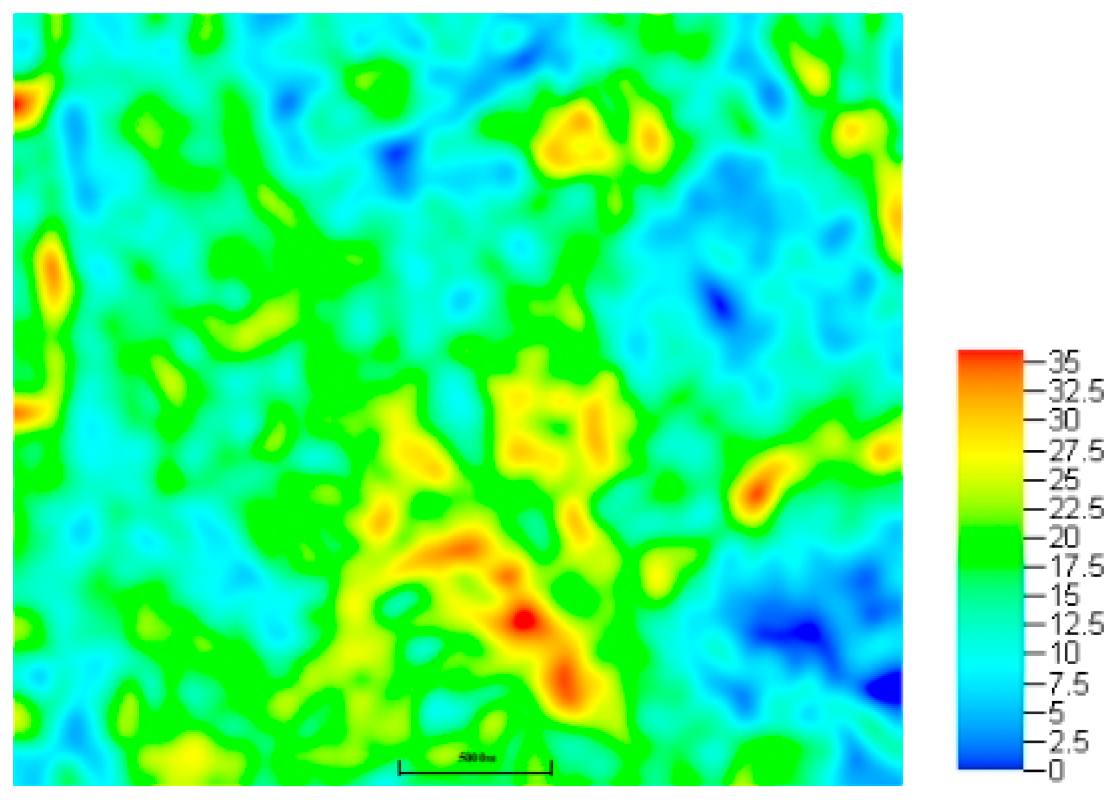

- (3)

- For different fracture facies types, seismic attributes such as coherence, curvature, ant body, and thickness were analyzed. The neural network algorithm method indicated that the prediction results for multiattribute fracture densities in the different fracture facies were consistent with the image logs. The plane distribution of the fracture density effectively reflects the fracture facies’ characteristics, and the method mentioned in this paper is reliable. Fractures are one of the key factors that influence the development of “sweet points” within tight sandstone reservoirs. The predictive results for the fractures could effectively indicate the location of a “sweet point”. The fracture prediction method based on the complex lithologic fracture facies model is important for target optimization in tight gas exploration and productivity breakthroughs in tight sandstone gas wells.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keles, C.; Vasilikou, F.; Ripepi, N.; Agioutantis, Z.; Karmis, M. Sensitivity analysis of reservoir conditions and gas production mechanism in deep coal seams in Buchanan County, Virginia. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2019, 94, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yang, S.; Qian, W.; Sun, Q.; Jiang, X.; Zang, H. China’s unconventional natural gas development: Status and prospects. Environ. Impact Assess. 2020, 42, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Jia, A.; Wei, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhu, H. Progress and development prospects of shale gas exploration and development in China. China Pet. Explor. 2020, 25, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, C.; Zu, R.; Wu, S.; Yang, Z.; Tao, S.; Yuan, X.; Hou, L.; Yang, H.; Xu, C.; Li, D.; et al. Types, characteristics, genesis and prospects of conventional and unconventional hydrocarbon accumulations: Taking tight oil and tight gas in China as an instance. Acta Pet. Sin. 2012, 33, 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Ge, Z.; Chen, C.; Hou, Y.; Ye, M. Current Status and Effective Suggestions for Efficient Exploitation of Coalbed Methane in China: A Review. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 9102–9123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Pei, L.; Lei, D.; Zeng, B. Distribution and development status of unconventional natural gas resources in China. Pet. Geol. Recover. Effic. 2015, 1, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Meng, S.; Gao, L.; Sun, X.; Duan, C.; Wang, H. Assessments on potential resources of deep coalbed methane and compact sandstone gas in Linxing Area. Coal Sci. Technol. 2015, 43, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, B.; Qin, Y.; Cao, G.; Zhang, H. Method for calculating the fracture porosity of tight-fracture reservoirs. Geophysics 2016, 81, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkestad, A.; Veselovsky, Z.; Roberts, P. Utilising borehole image logs to interpret delta to estuarine system: A case study of the subsurface Lower Jurassic Cook Formation in the Norwegian northern North Sea. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2012, 29, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, M.S. Fracture and in-situ stress patterns and impact on performance in the khuff structural prospects, eastern offshore Saudi Arabia. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2014, 50, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosari, E.; Ghareh-Cheloo, S.; Kadkhodaie-Ilkhchi, A.; Bahroudi, A. Fracture characterization by fusion of geophysical and geomechanical data: A case study from the Asmari reservoir, the Central Zagros fold-thrust belt. J. Geophys. Eng. 2015, 12, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.H.; Smith, V.; Brown, A. Developing a model discrete fracture network, drilling, and enhanced oil recovery strategy in an unconventional naturally fractured reservoir using integrated field, image log, and three-dimensional seismic data. AAPG Bull. 2015, 99, 735–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brekke, H.; MacEachern, J.A.; Roenitz, T.; Dashtgard, S.E. The use of microresistivity image logs for facies interpretations: An example in point-bar deposits of the McMurray Formation, Alberta, Canada. AAPG Bull. 2017, 101, 655–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, J.; Joubert, J.B. Glacial sedimentology interpretation from borehole image log: Example from the Late Ordovician deposits, Murzuq Basin (Libya). Interpretation 2016, 4, B1–B16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshbakht, F.; Azizzadeh, M.; Memarian, H.; Nourozi, G.H.; Moallemi, S.A. Comparison of electrical image log with core in a fractured carbonate reservoir. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2012, 86, 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Muniz, M.C.; Bosence, D.W.J. Pre-salt microbialites from the campos basin (off-shore Brazil): Image log facies, facies model and cyclicity in lacustrine carbonates. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2015, 418, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhou, Z.; Lai, J.; Dai, Q.; Chen, J.; Fan, X.; Wang, S. Identification of lithology and lithofacies type and its application to Chang 7 tight oil in Heshui area. Ordos Basin. Chin. Geol. 2016, 43, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, G.; Ran, Y.; Lai, J.; Cui, Y.; Zhao, X. A logging identification method of tight oil reservoir lithology and lithofacies: A case from Chang 7 Member of Triassic Yanchang Formation in Heshui area, Ordos Basin, NW China. Petrol. Explor. Dev. 2016, 43, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, C. A new method to calculate lithological profile with micro-resistivity imaging log. Well Logging Technol. 2008, 32, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, S.; Cao, J.; Li, M.; Pang, X.; Han, C.; Fan, X.; Yang, L.; He, Z.; et al. A review on the applications of image logs in structural analysis and sedimentary characterization. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2018, 95, 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xue, L.; Pan, B. Lithology identification of igneous rock using FMI texture analysis. Well Logging Technol. 2009, 33, 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M.E.J.; Lewis, D.; Yogi, O.; Holland, D.; Hombo, L.; Goldberg, A. Development of a Papua New Guinean onshore carbonate reservoir: A comparative borehole image (BHI) and petrographic evaluation. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2013, 44, 164–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BinAbadat, E.; Bu-Hindi, H.; Lehmann, C.; Kumar, A.; AL-Harbi, H.; AL-Ali, A.; Al Katheeri, A. A Workflow to Integrate Core and Image Logs in Order to Enhance the Characterization of Subsurface Facies on Carbonate Reservoirs, Offshore Abu Dhabi. In Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition and Conference, SPE, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 12–15 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- You, Z.; Du, X.; Hou, H.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, H. Discussion on Imaging Log Interpretation Mode. Well Logging Technol. 2000, 24, 393–399. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.; Wang, G.; Huang, L.; Li, W.; Ran, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, J. Brittleness index estimation in a tight shaly sandstone reservoir using well logs. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2015, 27, 1536–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Chen, G.; Zeng, Q.; Zhou, C. Sedimentary microfacies and palaeogeomorphology as well as their controls on gas accumulation within the deep-buried cretaceous in Kuqa depression, Tarim basin, China. J. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2016, 1, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, M.S.; MacPherson, K.; Al-Marhoon, M.I.; Rahim, Z. Diverse fracture properties and their impact on performance in conventional and tight-gas reservoirs, Saudi Arabia: The Unayzah, South Haradh case study. AAPG Bull. 2012, 96, 459–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, W.; Zeng, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, G.; Zu, K. Fracture responses of conventional logs in tight-oil sandstones: A case study of the Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation in southwest Ordos Basin, China. AAPG Bull. 2016, 100, 1399–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ding, W.; Wang, R.; Yang, S.; Yang, H.; Gu, Y. Simulation of paleotectonic stress fields and quantitative prediction of multi-period fractures in shale reservoirs: A case study of the niutitang formation in the lower Cambrian in the Cen’gong block, South China. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2017, 84, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, W.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, B.; Miao, F.; Lyu, P.; Dong, S. Influence of natural fractures on gas accumulation in the Upper Triassic tight gas sandstones in the northwestern Sichuan Basin, China. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2017, 83, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshbakht, F.; Memarian, H.; Mohammadnia, M. Comparison of Asmari, Pabdeh and Gurpi formation’s fractures, derived from image log. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2009, 67, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, M.S. Fracture modes in the Silurian Qusaiba shale play, northern Saudi Arabia and their geomechanical implications. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2016, 78, 312–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y. Study on Artificial Fracture System in Block 9 of Cainan Oilfield. J. Southwest Pet. Univ. 2003, 25, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.; Wang, G.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, L.; Han, C.; Wu, D.; Huang, L.; Luo, G. Quantitative evaluation of tight gas sandstone reservoirs of Bashijiqike formation in Dabei gas field. J. Cent. South Univ. 2015, 46, 2285–2298. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, C.; Shi, W.; Hu, B. Neotectonic Evolution of the Peripheral Zones of the Ordos Basin and Geodynamic Setting. Geol. J. China Univ. 2006, 12, 285–297. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. The Research of Fractures in the Ha’nan Oilfield. Master’s Thesis, Northwest University, Xi’an, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Bai, H. Physical Simulation Experiment of Normal Faults Associated Fractures. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2010, 36, 8975–8979. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, L. Study on Reservoir Fracture Prediction; Petroleum Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Yu, X.; Li, S.; Chen, G. Improving the accuracy of geological model by using seismic forward and inversion techniques. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2014, 41, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, W.; Di, B.; Wei, J. Seismic responses of tight gas sand of different water saturations: A physical model research. In SEG Technical Program Expanded Abstracts 2013; Society of Exploration Geophysicists: Houston, TX, USA, 2013; pp. 2592–2596. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, N.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Xia, H.; She, G. Seismic detection and prediction of tight gas reservoirs in the Ordos Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2008, 29, 668–675. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, T.; Fu, S.; Lyu, Q.; Lai, W. Application of multiwave joint inversion to the prediction of relatively high-quality reservoirs—An example from the prediction of deep tight clastic sandstone reservoirs in the western Sichuan Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2009, 30, 357–362. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. Key techniques of integrated seismic reservoir characterization for tight oil & gas sands. Prog. Geophys. 2014, 29, 182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Xia, Z.; Wang, C.; Song, G.; Wei, X.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, B. Seismic prediction for sweet spot reservoir of tight oil. J. Jiliin Univ. 2015, 45, 602–610. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Cheng, L.; Liu, J.; Xie, Q.; Huang, S.; Huang, Z. Research and application of post-stack seismic attributes in recognizing shale gas reservoir fracture. Coal Geol. Explor. 2015, 43, 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Caers, J. Petroleum Geostatistics; Society of Petroleum Engineers: Richardson, TX, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bardou, E. Markov Processes and Their Applications; Higher Education Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, G. Detection of Natural Fractures from Observed Surface Seismic Data Based on a Linear-Slip Model. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2018, 175, 2769–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Gui, Z. Application of multiple post-stack seismic attributes in the prediction of carboniferous fracture in west Hashan. Prog. Geophys. 2014, 29, 1772–1779. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Jia, Y.; Wei, S.; Zheng, W. The integrated poststack fracture prediction of Xusi formation in Xinchang survey. Geophys. Geochem. Explor. 2014, 38, 1038–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Q.; Qu, S.; Li, Z.; Sun, Z.; Chen, Y. Fracture prediction by using pre-stack and post-stack seismic techniques in S2 block, Yemen. Geophys. Prospect. Pet. 2014, 53, 603–608. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Logging Evaluation Technique for Tight Clastic Reservoir in Area of West Sichuan. Well Logging Technol. 2004, 28, 419–422. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Zhu, Q.; Peng, S. Artificial neural network pattern recognition of fractures in the bedrock reservoir of the Qijia buried hill. Geophys. Geochem. Explor. 2007, 32, 160–163. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Yan, T.; Tu, H. Application of artificial neural network to identification of drilled strata. Earth Sci.-J. China Univ. Geosci. 2000, 25, 642–645. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Cheng, L.; Mou, J.; Zhao, W. A new fracture prediction method by combining genetic algorithm with neural network in low-permeability reservoirs. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2014, 121, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Qu, X.; Wang, C.; Lei, Q.; Cheng, L.; Yang, Z. Natural fracture distribution and a new method predicting effective fractures in tight oil reservoirs of Ordos Basin. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2016, 43, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Huang, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, L.; Pan, Y. Quantitative evaluation of fracture development in Triassic Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2015, 42, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajornrit, J.; Chaipornkaew, P. A comparative study of ensemble back-propagation neural network for the regression problems. In Proceedings of the 2017 2nd International Conference on Information Technology (INCIT), Nakhonpathom, Thailand, 2–3 November 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

| Well | Formation | Depth (m) | Lithology | Fracture Parameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top Depth | Bottom Depth | Types | Number | Cutting Depth (cm) | Width (mm) | Dip Angles | |||

| A | Taiyuan Formation | 1538 | 148.45 | carbonaceous mudstone | tectonic fractures | 1 | 8 | 0.5 | 40° |

| Taiyuan Formation | 1703.48 | 1703.53 | coarse sandstone | tectonic fractures | 1 | 5 | 0.5 | 30° | |

| Taiyuan Formation | 1735.09 | 1735.34 | mudstone | tectonic fractures | 1 | 25 | 1 | 75° | |

| D | Upper Shihezi Formation | 1790.38 | 1790.48 | siltstone | tectonic fractures | 1 | 10 | 1 | 50° |

| Lower Shihezi Formation | 1792.38 | 1792.63 | mudstone | tectonic fractures | 1 | 25 | 2 | 80° | |

| G | Upper Shihezi Formation | 1206.65 | 1206.85 | fine sandstone | tectonic fractures | 1 | 20 | 2 | 80° |

| Taiyuan Formation | 1631.44 | 1631.54 | carbonaceous mudstone | tectonic fractures | 1 | 10 | 1 | 75° | |

| J | Taiyuan Formation | 1639.26 | 1639.31 | medium sandstone | tectonic fractures | 1 | 5 | 0.3 | 60° |

| Taiyuan Formation | 1754.65 | 1754.9 | fine sandstone | tectonic fractures | 1 | 25 | 2 | 60° | |

| M | Lower Shihezi Formation | 1616.43 | 1622.87 | silty mudstone | bedding fractures | a group | <0.1 | ||

| Taiyuan Formation | 1620 | 1620.2 | muddy siltstone | bedding fractures | a group | <0.1 | |||

Lmaging Festures  | Different Image Descriptions | Lithology | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A large number of messy dark spots distributed in the brown background reflecting coarse grains; bedding is not obvious. |  | coarse sandstone |

| A large number of messy dark spots distributed in the brown background; these grains are smaller than those of coarse sandstone; and a small amount of parallel bedding was observed. |  | medium sandstone |

| Bedding was observed in the blurred brown background; and dark tiny spots were observed. |  | fine sandstone |

| Bedding was observed in the blurred brown background; a large number of spots were observed; and the spots were finer than that of sandstone. |  | siltstone |

| Bedding is less developed than mudstone, bright stripes and dark stripes appeared interactively; a large number of blurred dark tiny spots occurred. |  | muddy siltstone |

| Massive bedding or horizontal bedding developed intensively in dark or bright background. The shallow mudstone developed a block structure and easily collapsed, as shown in the dark shadow region. The deep mudstone mostly developed horizontal bedding. |  | mudstone |

| Thick bright horizontal bedding and thin dark horizontal bedding are mostly reflected by bright yellow background. Black or bright white spots occurred. |  | carbonaceous mudstone |

| Dark horizontal bedding occurred in bright yellow background. Stripes were less developed than in mudstone, and bright stripes and dark stripes appeared interactively; blurred dark tiny spots occurred. |  | silty mudstone |

| The color was bright white and well-distributed, variegated color occurred occasionally, and was easily distinguished from surrounding rock; a large number of brown spots occurred in the bright background, and mostly horizontal bedding and dark fractures developed. |  | coal |

| Fractures | Lithology | Fracture Density (Number/Meter) | Cutting Depth (m) | Opening (mm) | Classification of Fracture Facies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bedding fractures | Carbonaceous mudstone | 15.15 | 0.09 | Well-developed fracture facies | |

| Mudstone | 11.04 | 0.05 | |||

| Silty mudstone | 8.06 | 0.03 | |||

| Siltstone | 6.05 | 0.02 | |||

| Muddy siltstone | 4.66 | 0.02 | Poorly developed fracture facies | ||

| Coal | 4.47 | 0.03 | |||

| Fine sandstone | 3.36 | 0.01 | |||

| Coarse sandstone | 2.33 | 0.02 | |||

| Medium sandstone | 2.1 | 0.01 | Undeveloped fracture facies | ||

| N10° tectonic fracture | Carbonaceous mudstone | 6.54 | 0.2 | 0.8 | Well-developed fracture facies |

| Coarse sandstone | 4.96 | 0.5 | 0.6 | ||

| Silty mudstone | 2.84 | 0.62 | 1 | ||

| Siltstone | 0.9 | 0.76 | 0.5 | Poorly developed fracture facies | |

| Mudstone | 0.76 | 0.89 | 0.7 | ||

| Medium sandstone | 0.65 | 0.92 | 1 | ||

| Fine sandstone | 0.64 | 1 | 0.6 | ||

| Coal | 0.05 | 0.2 | 2 | Undeveloped fracture facies | |

| Muddy siltstone | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 | ||

| N100° tectonic fracture | Carbonaceous mudstone | 2.88 | 0.3 | 1.2 | Well-developed fracture facies |

| Mudstone | 1.29 | 0.52 | 0.9 | Poorly developed fracture facies | |

| Muddy siltstone | 1.24 | 0.59 | 0.8 | ||

| Siltstone | 1.11 | 0.65 | 0.6 | ||

| Coarse sandstone | 0.51 | 0.78 | 0.7 | Undeveloped fracture facies | |

| Silty mudstone | 0.36 | 0.93 | 0.8 | ||

| Coal | 0.22 | 0.25 | 1.8 | ||

| Fine sandstone | 0.2 | 0.75 | 0.5 | ||

| Medium sandstone | 0.08 | 0.87 | 0.4 |

| Formation | Lithology | Carbonaceous Mudstone | Coal | Mudstone | Silty Mudstone | Coarse Sandstone | Medium Sandstone | Fine Sandstone | Siltstone | Muddy Siltstone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Shihezi Formation | Length (m) | 1176 | 970 | 1399 | 2589 | 3122 | 2924 | 1344 | ||

| Width (m) | 1060 | 865 | 1045 | 2493 | 2934 | 2339 | 1045 | |||

| Thickness (m) | 5.5 | 2.3 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 3.5 | |||

| Lower Shihezi Formation | Length (m) | 3122 | 970 | 1399 | 1755 | 1635 | 2652 | 1344 | ||

| Width (m) | 2955 | 865 | 1045 | 1313 | 1445 | 2581 | 1045 | |||

| Thickness (m) | 12 | 12 | 6.8 | 6.5 | 6.3 | 3.8 | 3.5 | |||

| Shanxi Formation | Length (m) | 1344 | 2597 | 970 | 1189 | 2419 | 2280 | 2473 | 1344 | |

| Width (m) | 1012 | 2296 | 865 | 1054 | 2238 | 2272 | 2335 | 1045 | ||

| Thickness (m) | 2.7 | 7.1 | 8.8 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 3 | 2.2 | ||

| Taiyuan Formation | Length (m) | 1344 | 1149 | 1136 | 970 | 2818 | 2970 | 1783 | 2762 | 1344 |

| Width (m) | 1012 | 1012 | 1040 | 865 | 2721 | 2895 | 1735 | 2536 | 1045 | |

| Thickness (m) | 4 | 5.4 | 6.1 | 2.6 | 6.4 | 4 | 5.3 | 4.2 | 4.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Ren, Z.; Chen, X.; He, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Z.; Hu, Y. Fracture Prediction Based on a Complex Lithology Fracture Facies Model: A Case Study from the Linxing Area, Ordos Basin. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13277. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413277

Zhao Y, Ren Z, Chen X, He W, Zhang Z, Wei Z, Hu Y. Fracture Prediction Based on a Complex Lithology Fracture Facies Model: A Case Study from the Linxing Area, Ordos Basin. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13277. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413277

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Yangyang, Zhicheng Ren, Xiaoming Chen, Wenxiang He, Zhixuan Zhang, Zijian Wei, and Yong Hu. 2025. "Fracture Prediction Based on a Complex Lithology Fracture Facies Model: A Case Study from the Linxing Area, Ordos Basin" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13277. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413277

APA StyleZhao, Y., Ren, Z., Chen, X., He, W., Zhang, Z., Wei, Z., & Hu, Y. (2025). Fracture Prediction Based on a Complex Lithology Fracture Facies Model: A Case Study from the Linxing Area, Ordos Basin. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13277. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413277