1. Introduction

The food industry generates a considerable number of by-products after processing plant or animal ingredients. The global Food Waste Index was 1.05 billion tonnes in 2022, as reported in the UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2024 [

1]. Food waste includes shells, seeds, whey, bones, skin, and oil cake. Every year, millions of tonnes of tomatoes are processed to produce commercial products such as ketchup, juice, and sauce [

2,

3]. The main problem with tomato processing is waste. Globally, approximately 60 million tonnes of tomatoes are wasted annually. Recycling this waste reduces economic and energy costs and increases product yield [

3,

4]. An important source of waste is by-products from the tomato and sugar beet processing industries. These waste materials are valuable resources used for animal feed, fermentation, and the production of biofuels, chemicals, and food ingredients. Major waste products include peels, seeds, beet pulp, molasses, and other liquids, which can be transformed by various methods into new products [

5,

6].

By-products are usually rich in valuable bioactive compounds that can be valorized for various purposes, increasing sustainability and reducing waste [

7]. In the food industry, by-products such as tomato peels and sugar beet leaves are often processed through extraction procedures to isolate compounds like carotenoids, chlorophylls, polyphenols, and vitamins, which can then be used as food supplements. These bioactive compounds exhibit strong antioxidant, anti-cancer, and anti-inflammatory properties [

8,

9]. Because of their valuable role in the human diet, it is important to preserve these compounds during processing. Tomato by-products, especially seeds and peels, are rich in lycopene. Lycopene is a natural pigment with a characteristic red color, produced by its distinctive chemical structure of 11 conjugated bonds, which allows lycopene to isomerize into 72 possible conformations. In addition to its strong antioxidant properties, lycopene plays an important role in protecting the human body from cancer and cardiovascular diseases [

10]. The stability of lycopene depends on temperature, exposure to light, and processing technology. The development of new non-thermal technologies should enable better lycopene extraction with higher yield and efficiency [

11,

12].

There are numerous methods for processing by-products, most of which are thermal-based. Traditional extraction methods involve the use of large amounts of organic solvents, which are usually toxic, and the extraction process is often time-consuming. The development of novel, non-thermal technologies should reduce extraction time and the use of organic solvents during processing. Recently, pretreatments and treatments such as pulsed electric fields (PEF), high-voltage electrical discharge (HVED), as well as microwave-assisted extraction (MWE), ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), and supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) have been increasingly used for the extraction of bioactive components [

13,

14,

15]. Non-thermal techniques can increase extraction without compromising nutrient quality [

16]. Green technologies such as MWE, HVED, PEF, and UAE are the preferred methods for this process [

17,

18]. Sustainability will be at the forefront of research activities to achieve the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The aim of this work was to investigate the properties of cold-plasma technology as a non-thermal technology in the extraction of chlorophylls, carotenoids, and polyphenols from tomato peels and sugar beet leaves. The use of cold-plasma technology on sugar beet leaf by-products has largely been unexplored. On the other hand, to optimize the cold-plasma procedures as much as possible, monitoring the quality must be adjusted and applied to this specific technology. Therefore, in our work, Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) spectroscopy, an advanced analytical technique that provides innovative solutions, was used for quality control. As one of the most informative and selective methods for food analysis, EPR offers a highly sensitive approach for detecting and characterizing free radicals and paramagnetic species in various food systems [

19,

20]. The EPR technique is based on the interaction of unpaired electrons with an external magnetic field, enabling the identification of short-lived species that are often undetectable by conventional analytical methods. EPR spectroscopy can be applied to monitor and quantify changes in foods processed by innovative technologies such as ionizing radiation, high pressure, pulsed electric fields, ultrasound, and microwaves. It also enables the evaluation of oxidation processes and the assessment of antioxidant activity in complex food systems [

21,

22]. Furthermore, EPR spectroscopy has emerging potential for tracing the origin and transformation of food waste, thereby supporting sustainable approaches in the food industry.

The aim of this study was to optimize the cold-plasma extraction process regarding solvent ratio, treatment time, and energy input for two types of by-products. In this study, tomato peel and sugar beet leaves were selected as raw materials for the isolation of bioactive compounds because they are readily available and often underutilized by-products of the food industry [

8,

23]. The tomato and sugar beet industries generate substantial amounts of by-products and waste due to seasonal overproduction and strict market standards, contributing to economic losses and environmental impact. However, these by-products have significant potential for valorization [

24]. Although they have high antioxidant potential, these plant residues are rarely utilized in practice and therefore represent a valuable resource for obtaining bioactive substances [

25,

26]. Their use in this research supports sustainability efforts, reduces organic waste, and promotes more efficient biomass valorization. The determination of bioactive components and EPR analyses of inherently present radicals and antioxidant activity were conducted. Paramagnetic ions, such as Fe

2 and Mn

2+, were monitored by EPR spectroscopy in the samples before plasma treatment. Furthermore, antioxidant activity was determined by EPR after treatment. The results show that the antioxidant activity depends on the type of treatment.

Currently, many benchtop EPR devices are commercially available, enabling easy monitoring and analysis at both laboratory and industrial scales. Here we present the potential use of a benchtop EPR device in innovative quality control concepts throughout the entire process “from farm to fork”, i.e., during processing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

All chemicals used in the analyses were HPLC grade. Methanol and n-hexane were purchased from VWR (Vienna, Austria). Folin–Ciocalteu reagent was obtained from Merck (Kenilworth, NJ, USA), while gallic acid was obtained from Thermo ScientificTM Chemicals (Waltham, MA, USA). Acetone and sodium carbonate were purchased from Kemika (Zagreb, Croatia), and 96% ethanol, 30% hydrogen peroxide, and L (+)-ascorbic acid were obtained from Gram-mol (Zagreb, Croatia). Iron (II) chloride tetrahydrate and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Sample Origin and Preparation

2.2.1. Origin and Preparation of the Tomato Peels

A plum-type tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L., cultivar “Roma”) was obtained from the Croatian Eco Farm “Vrtni centar Baković”, Sveti Filip i Jakov (43.9818° N, 15.4269° E), Croatia. The tomato peels were separated with a sharp knife after blanching in hot water for 10 s and immersing in cold water for approximately 30 s. The peels were then dried in a dryer (Elektrokovina, Zagreb, Croatia) at 70 °C until a constant mass was reached. The peels were ground in a mill to a powder consistency and stored in plastic cups at room temperature in a desiccator until analysis.

2.2.2. Origin and Preparation of the Sugar Beet Leaves

The sugar beet leaves (SBLs) (Beta vulgaris var. saccharifera L.), a herbaceous species of the Chenopodiaceae family, were received from the Croatian family business “Hrgović” in Kapinci (45.8126° N, 17.7008° E), Croatia. The SBLs were dried in a dryer at 50 °C to a constant mass, ground in a mill to a powder consistency, and stored in plastic cups at room temperature in a desiccator until analysis.

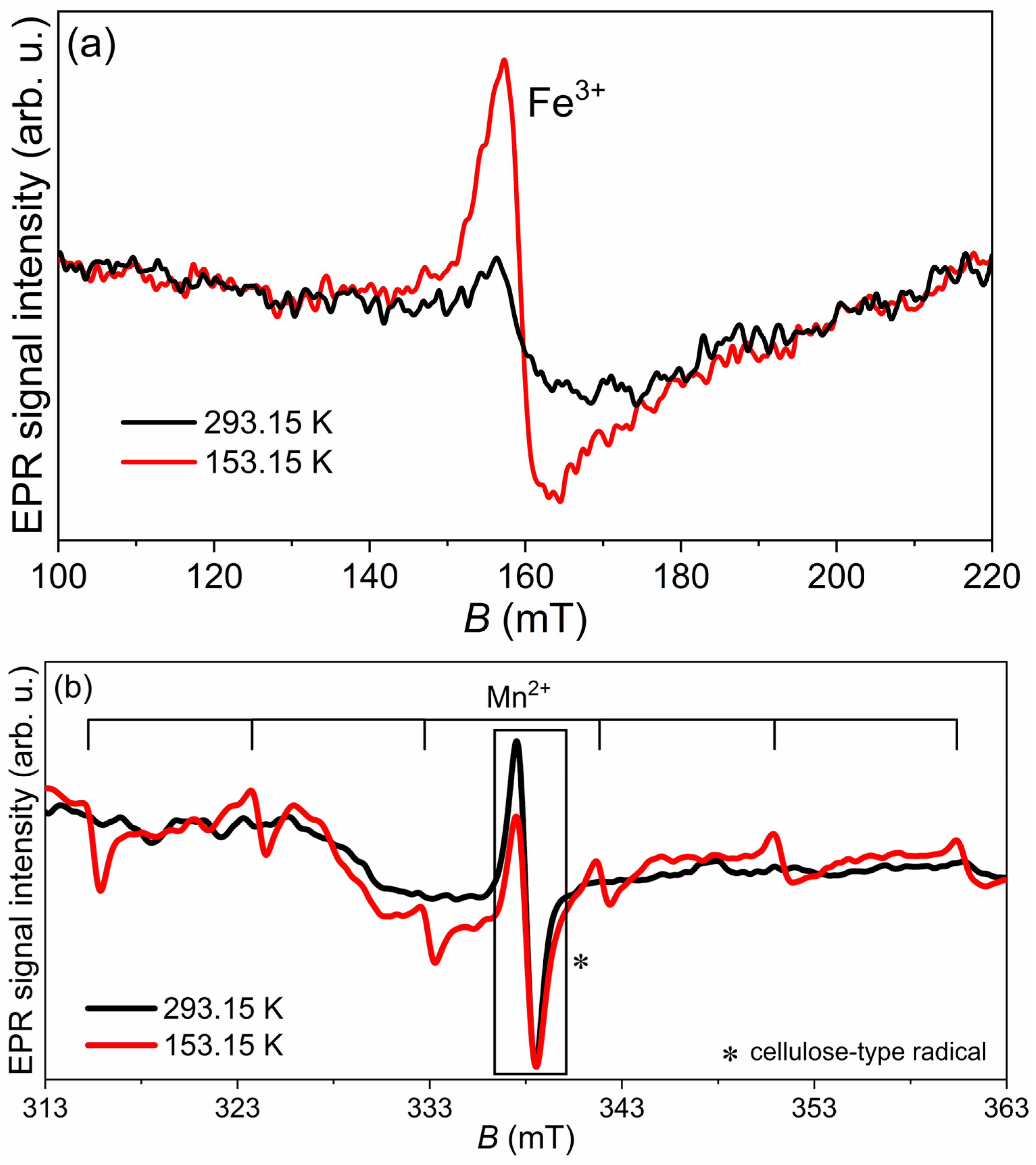

2.3. Transitional Metal Ions Detection by EPR Spectroscopy in Dried Raw Materials

EPR spectra of dried tomato peel and dried sugar beet leaves were recorded using a benchtop Bruker Magnettech ESR5000 spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin, Rheinstetten, Germany) operating at X-band frequency and equipped with N

2 temperature control. Technical specifications are provided in

Table 1.

EPR spectroscopy was used to detect the presence of transition metals in the dried tomato peel and SBLs before cold-plasma processing. In EPR tubes, 53.76 mg of SBLs and 18.20 mg of tomato peel powder were weighed. EPR spectra were recorded using the following parameters: the magnetic field was swept from 100 to 450 mT, the modulation amplitude was 0.5 mT, the microwave power was 5 mW, and the microwave frequency was 100 kHz. Measurements were performed at 293.15 K and 153.15 K.

2.4. Plasma Extraction Treatment of Bioactive Compounds from Tomato Peels and Sugar Beet Leaves

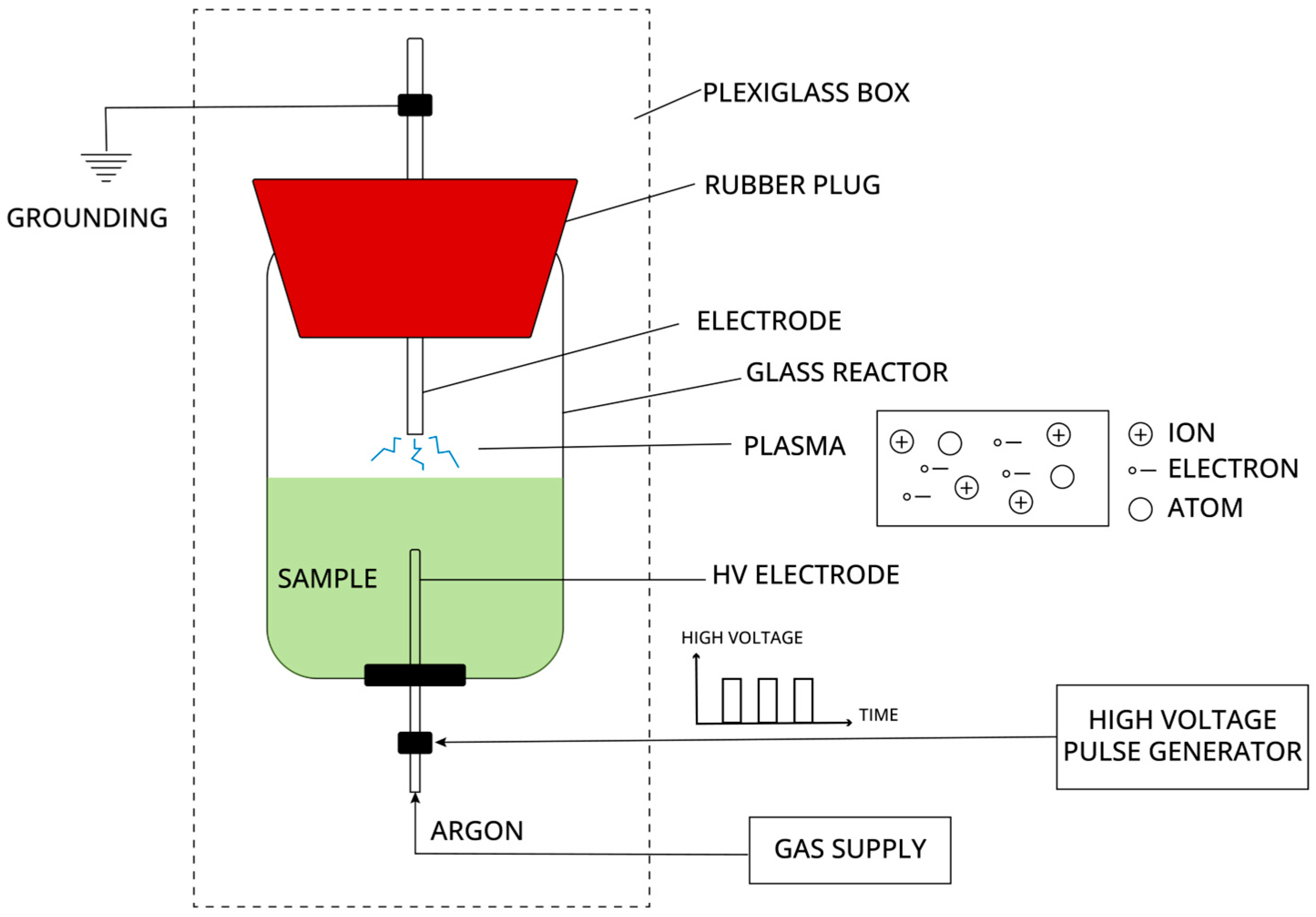

The plasma extraction treatment of bioactive compounds from the prepared samples (tomato peels and sugar beet leaves) was performed using High-Voltage Electrical Discharge (HVED). The experimental setup for HVED (

Figure 1) consisted of a closed Plexiglas box containing a glass reactor (up to 1000 mL, depending on the sample amount) with a point-to-point electrode configuration. A high-voltage electrode (a stainless steel medical needle) was placed in the liquid phase at the bottom of the reactor. A stainless steel electrode in the gas phase above the liquid surface served as the ground. The reactor was equipped with a rubber plug and adapted openings for electrodes and gas injection. The high-voltage pulse generator IMPEL HVG60/1 (IMPEL GROUP Ltd., Zagreb, Croatia) transmitted rectangular pulses through the HV electrode, with parameters set by the user (treatment time, pulse frequency, high voltage). The technical specifications of the generator are provided in

Table 2. Argon, used as the operating gas, was continuously injected through the HV electrode at the bottom of the reactor. Complete or partial ionization occurs when a high-voltage electrical current passes through a neutral fluid (in liquid and gas phases), resulting in electrical discharges, or plasma with increased conductivity.

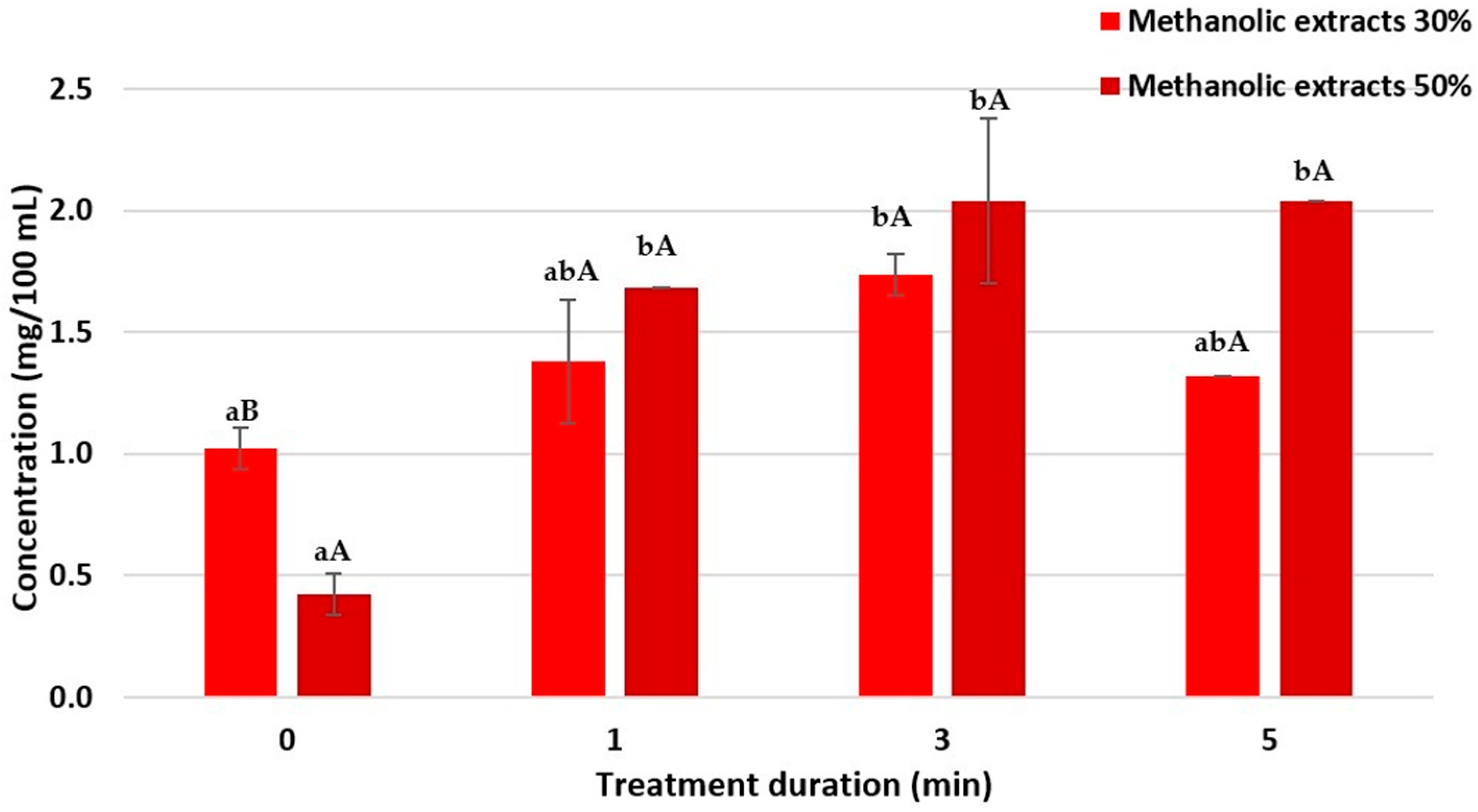

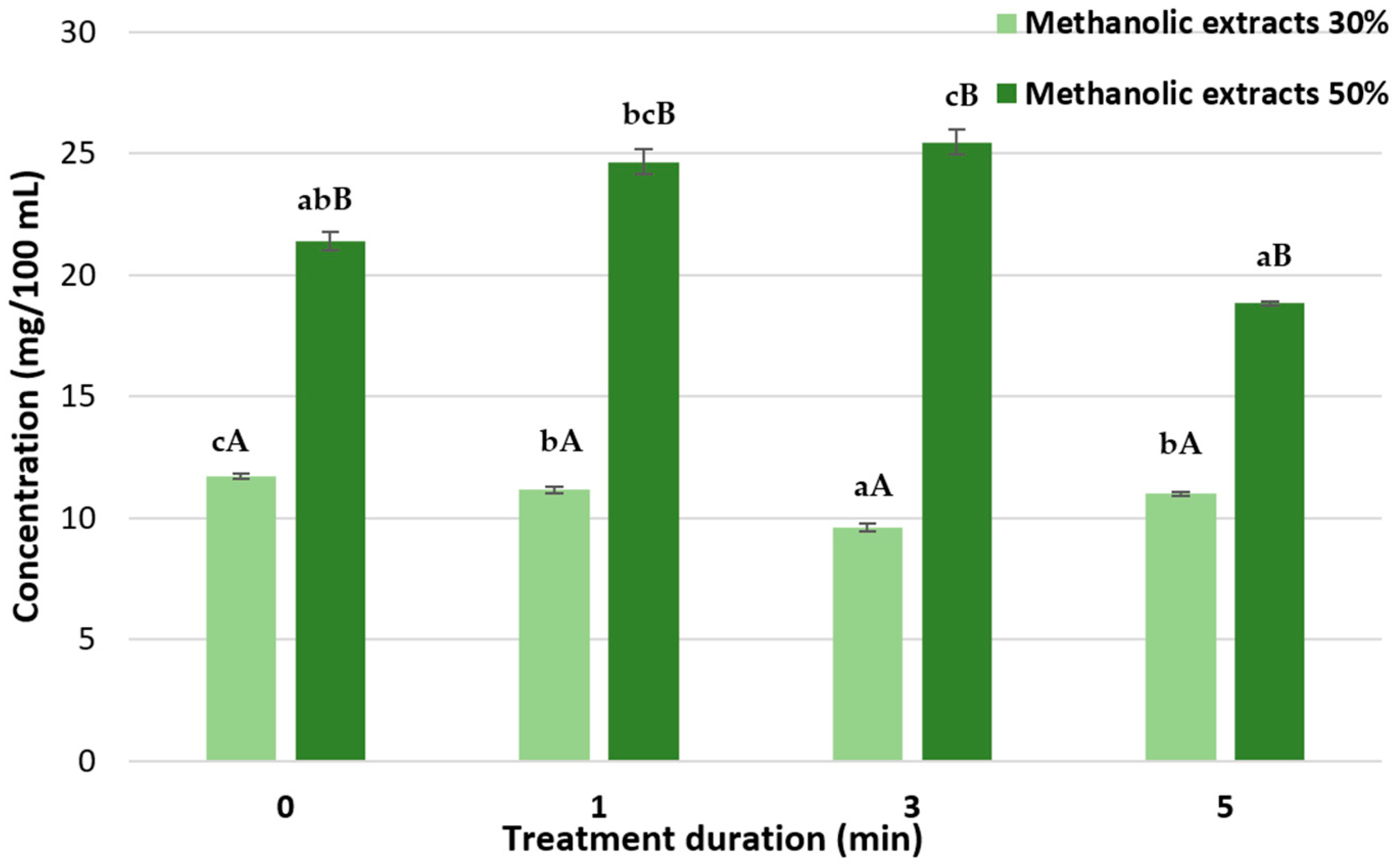

Two grams of tomato peel powder were suspended in 100 mL of 30% methanol solution and treated under the following parameters: treatment time of 0, 1, 3, and 5 min, pulse frequency 120 Hz, and voltage 30 kV. Everything was repeated for tomato peel powder with the 50% methanol solution. Bioactive compounds from sugar beet leaves were extracted using the same parameters in 100 mL of 30% and in 100 mL of 50% methanol solution.

2.5. Isolation of Bioactive Components

2.5.1. Total Polyphenolic Content in Tomato Peel Extracts and SBL Extracts

Polyphenolic compounds were extracted using 30% and 50% methanol solutions in an HVED plasma reactor. To determine the total polyphenolic content (TPC) in tomato peel and SBL samples, the Folin–Ciocalteu (FC) assay was used. A volume of 2 mL of Milli-Q water was mixed with 100 μL of the sample and 200 μL of FC reagent. The mixture was incubated for 3 min, then 1 mL of 20% sodium carbonate solution was added and mixed. The samples were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 2 h, after which absorbance at 765 nm was measured using a Secomam UviLine 9400 spectrophotometer (Secomam Groupe Aqualabo, Alès, France). A gallic acid calibration curve (0.06–0.3 mg/mL) was used to determine the total polyphenolic concentration in tomato peel and SBL samples, and results are expressed as mg/mL of gallic acid equivalents.

2.5.2. Total Carotenoid Content in Tomato Peel Extracts

After the treatment described in previous chapters, the methanolic layer was decanted from the samples, and the precipitate was suspended in 25 mL of a 4:6 (

v/

v) acetone:hexane solution to isolate carotenoid compounds. The prepared suspension was vortexed for 15 min at 3000 rpm using a Vortex V-1 Plus (Biosan, Riga, Latvia) and centrifuged with a Rotina 380 R centrifuge (Hettich, GmbH & Co. KG, Tuttlingen, Germany) at 2500 rpm for 10 min. Lycopene and beta-carotene concentrations were measured using a Secomam UviLine 9400 spectrophotometer (Secomam Groupe Aqualabo, Alès, France) at wavelengths of 663, 645, 505, and 453 nm, and concentrations were calculated using the following equations [

27]:

where A

663, A

645, A

505, and A

453 correspond to absorbance at 663, 645, 505, and 453 nm, respectively. The results are expressed as mg/100 mL.

2.5.3. Total Chlorophyll Content in SBLs

After the HVED plasma treatment, the methanolic layer was separated, and the precipitate was suspended in 25 mL of 80% acetone solution. The prepared suspension was vortexed for 15 min at 3000 rpm and centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 10 min. The total chlorophyll content was then measured using a Secomam UviLine 9400 spectrophotometer (Secomam Groupe Aqualabo, Alès, France) at 663 and 645 nm, and the concentration was calculated using the following equation [

28]:

where A

665 and A

645 correspond to absorbances at 665 and 645 nm, respectively. The results are expressed as mg/100 mL.

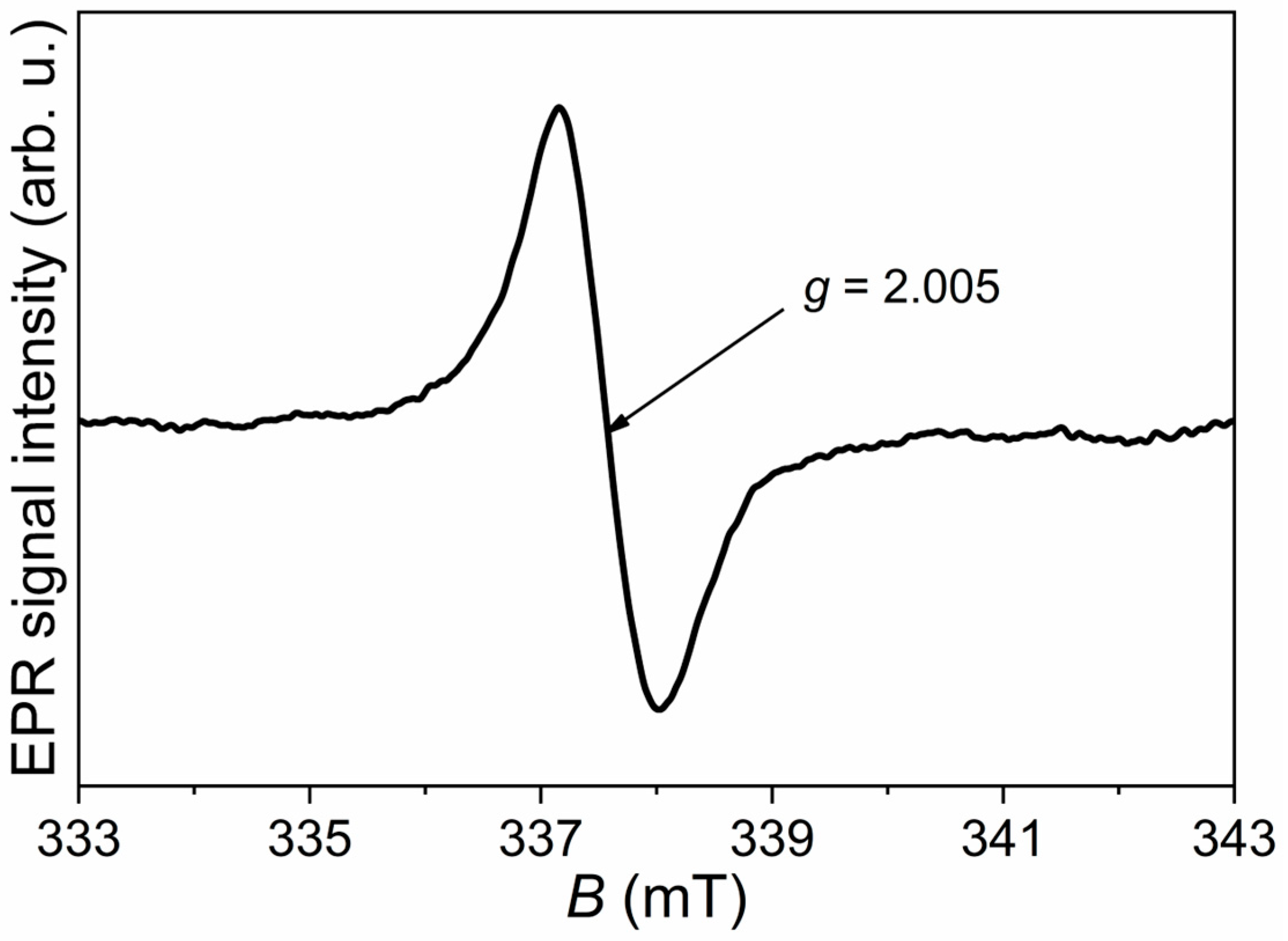

2.6. EPR Detection of Antioxidant Activity in Tomato Peel and Sugar Beet Leaf Powder Extracts

Antioxidant activity was determined using the EPR-DPPH assay. Antioxidants from tomato peels and SBLs react with the DPPH free radical, resulting in a decrease in DPPH concentration and EPR-DPPH signal intensity, which corresponds to the antioxidant activity of the investigated samples. The results are expressed as the percentage (%) reduction in EPR-DPPH signal intensity. A volume of 970 μL of 15 mM DPPH solution (in 96% ethanol) was mixed with 30 μL of the sample (tomato peel or SBL). Measurements were performed over 30 min with the following parameters: the magnetic field was swept from 331 to 343 mT, the modulation amplitude was 0.2 mT, the microwave power was 10 mW, and the microwave frequency was 100 kHz.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Systat v.13.2.01 (Grafiti LLC, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Measurements were performed in triplicate, and results are expressed as the mean of three consecutive measurements ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between results were determined using a t-test for the effect of two solvents, and a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test was used for other analyses. A p-value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Conclusions

Plasma technology, or HVED, is now recognized as an advanced non-thermal technology in many industries and is considered a modern technological standard. It has a wide range of applications, particularly in the food sector. Plasma can be generated under various conditions and in different environments. Monitoring, controlling, and adjusting plasma production parameters are important to ensure reproducible and reliable applications of advanced plasma technology in a stable environment.

In this experiment, HVED extraction proved to be an effective method for isolating bioactive compounds from tomato peel and sugar beet leaves (SBLs). The results show that HVED treatment duration and solvent concentration significantly influence the extraction of polyphenols, carotenoids, and chlorophylls. For tomato peel extracts, a 3 min HVED treatment was optimal for extracting total polyphenols and lycopene, while beta-carotene extraction improved with longer treatment times and higher solvent concentrations. In SBL extracts, HVED treatment did not have a statistically significant effect on total polyphenols, but it significantly influenced total chlorophyll content, with the highest concentrations observed in extracts obtained with higher solvent concentration after a 3 min treatment. These observations indicate that further optimization of HVED parameters may be necessary.

EPR measurements revealed the presence of Fe2+ and Mn2+ ions, as well as cellulose radicals in SBLs, while only cellulose radicals were detected in tomato peel, highlighting differences in radical composition between the plant matrices. HVED treatment generally improved the antioxidant properties of both extracts, with the highest activity observed after a 3 min treatment in most conditions, as confirmed by EPR-DPPH measurements.

These findings emphasize the need to optimize HVED parameters to maximize extraction efficiency and preserve bioactive compounds, highlighting the importance of dedicated optimization protocols for each extract type. EPR spectroscopy is highly suitable for monitoring and evaluating the impact of novel non-thermal technologies in food processing. EPR spectroscopy, through both direct and indirect methods, is indispensable for controlling food quality and guiding the development of new products, such as those based on the Mediterranean diet. Its advantages include the ability to determine key process parameters, monitor products during production and storage, and differentiate plant origin based on metal ion composition, which may reflect cultivation practices and soil characteristics.