Effect of Ozone and Drying Treatments on Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Bee Pollen

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

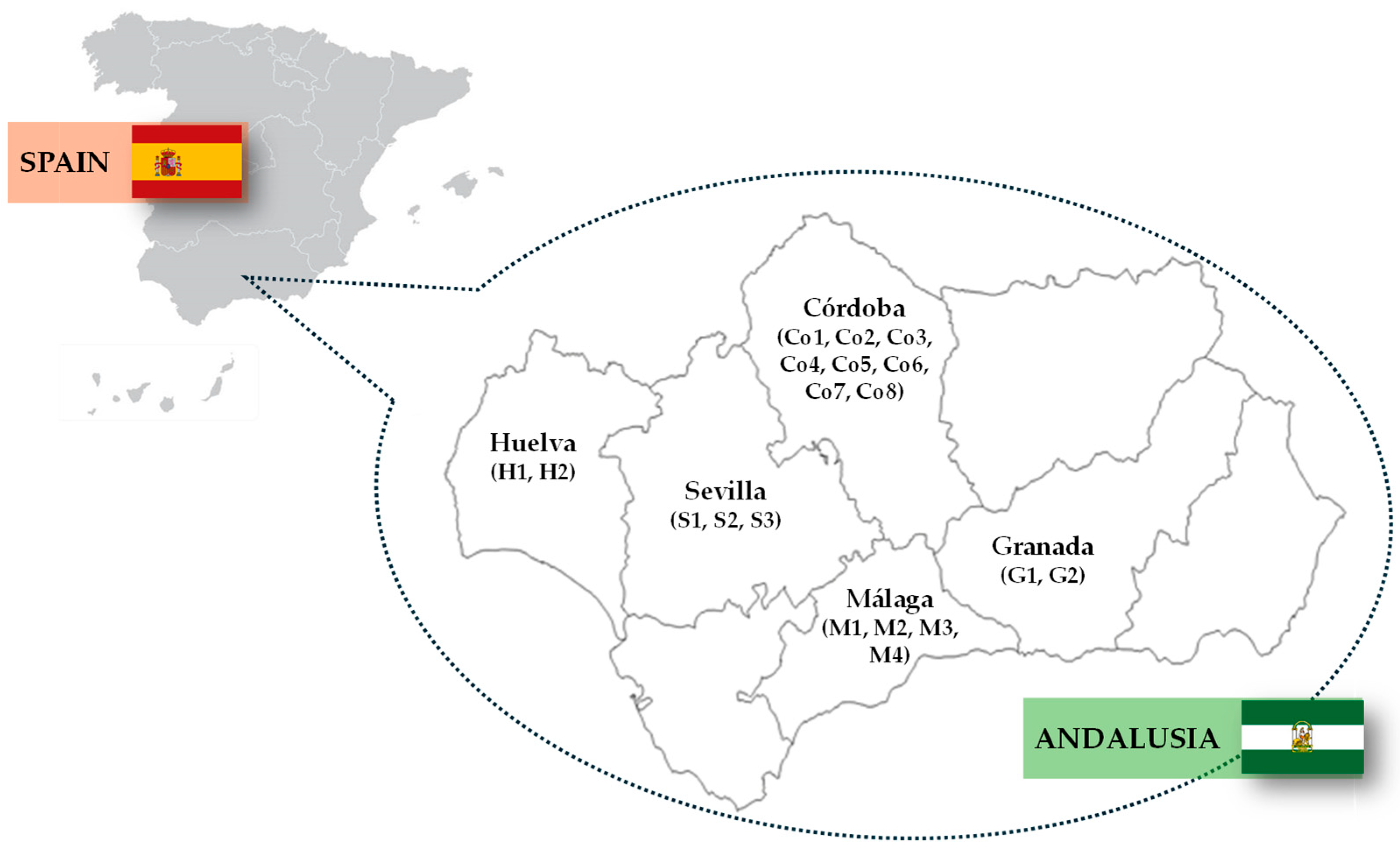

2.1. Bee Pollen Samples

2.2. Bee Pollen Sample Preparation

2.3. Total Phenolic Compounds

2.4. Antioxidant Activity

2.5. Determination of Botanical Origin

2.6. Data Analysis

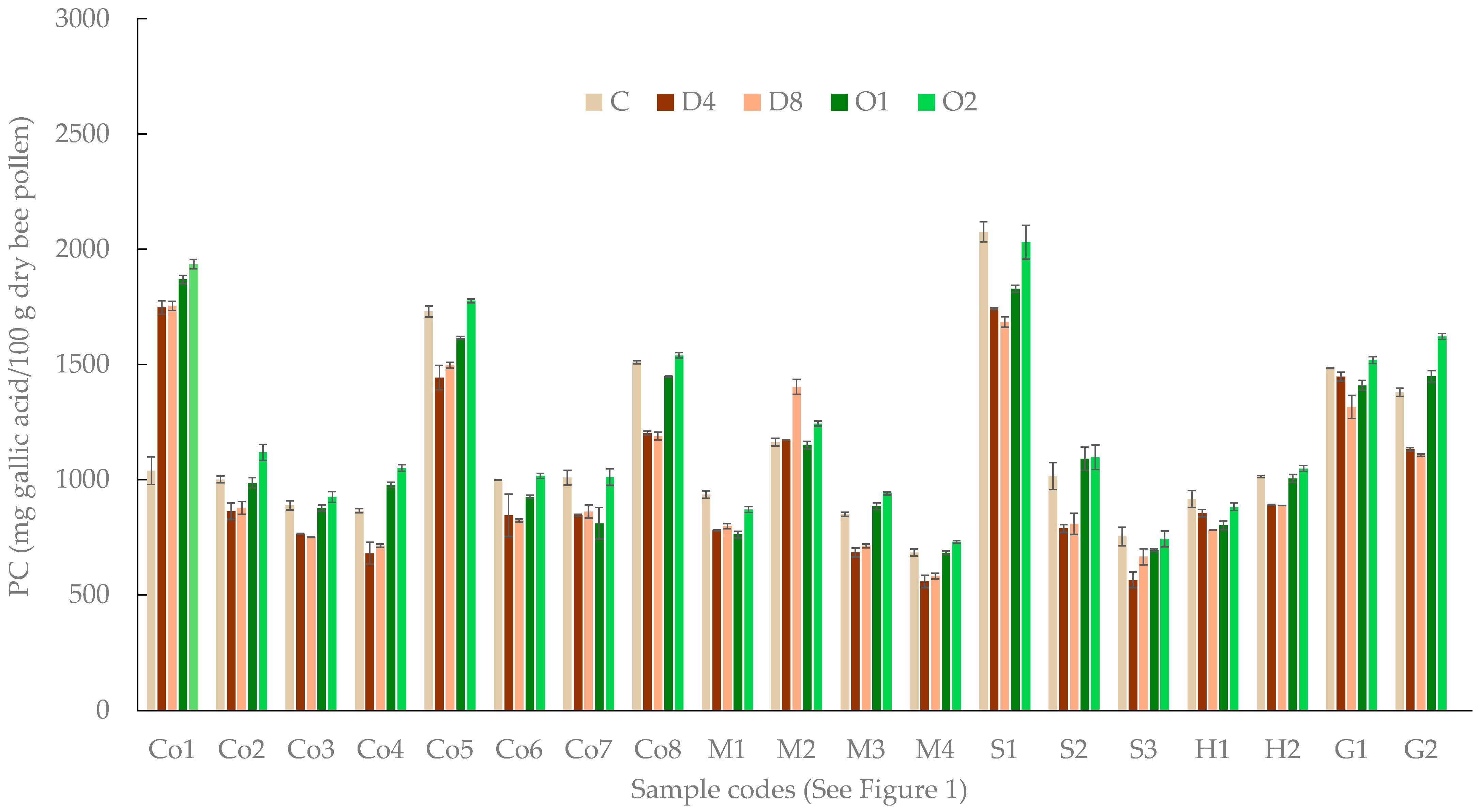

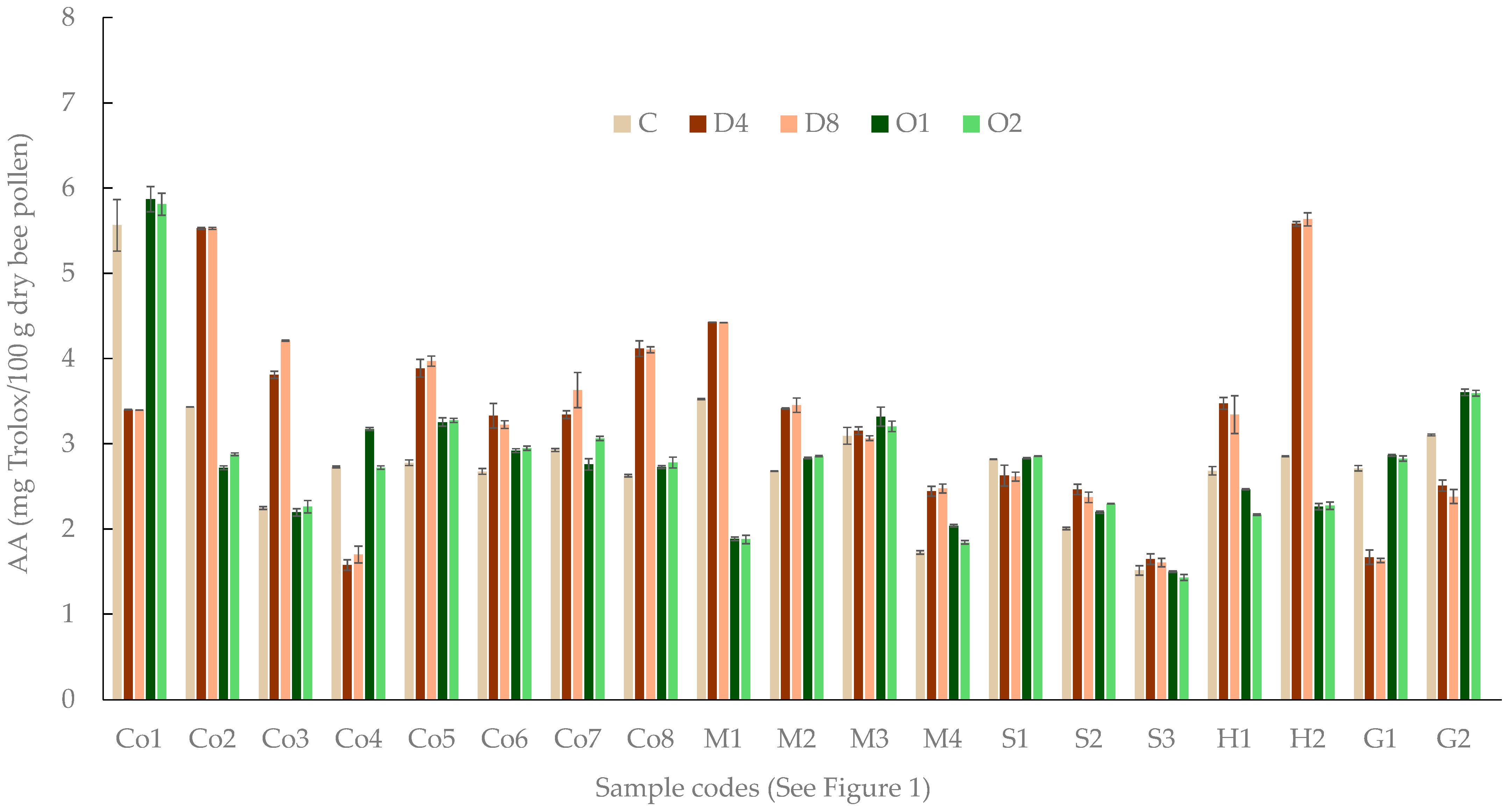

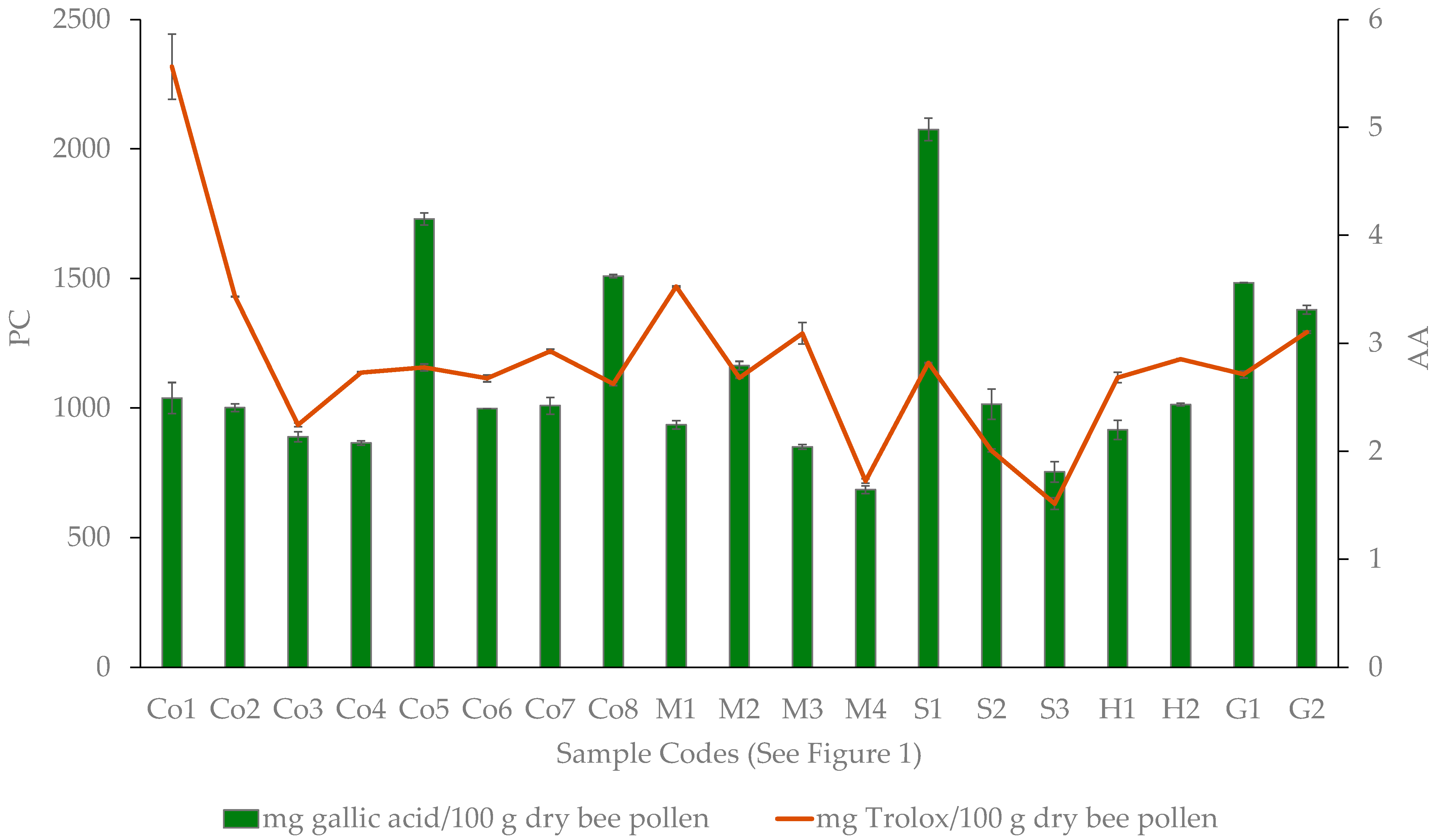

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PC | Phenolic compounds |

| AA | Antioxidant activity |

| O1 | Treatment with ozone, 1 h |

| O2 | Treatment with ozone, 2 h |

| D4 | Drying treatment, 4 h |

| D8 | Drying treatment, 8 h |

| C | Control, fresh bee pollen |

| Co1 to Co8 | Samples from Córdoba, Andalusia, Spain |

| M1 to M4 | Samples from Málaga, Andalusia, Spain |

| S1 to S3 | Samples from Sevilla, Andalusia, Spain |

| H1 and H2 | Samples from Huelva, Andalusia, Spain |

| G1 and G2 | Samples from Granada, Andalusia, Spain |

References

- Grand View Research. Bee Pollen Market Size & Trends Report, 2024; Grand View Research: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/bee-pollen-market-report (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Brodschneider, R.; Crailsheim, K. Nutrition and health in honey bees. Apidologie 2010, 41, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.G.R.; Bogdanov, S.; Almeida-Muradian, L.; Szczesna, T.; Mancebo, Y.; Frigerio, C.; Ferreira, F. Pollen composition and standardisation of analytical methods. J. Apic. Res. 2008, 47, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, D. Pollen Trapping and Storage; Primefact; NSW Department of Primary Industries: Orange, Australia, 2012; Volume 1126, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov, S. Pollen: Collection, Harvest, Compostion, Quality. Bee Product. Sci. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Stefan-Bogdanov/publication/304011810_Pollen_Collection_Harvest_Compostion_Quality/links/5762c0c808aee61395bef502/Pollen-Collection-Harvest-Compostion-Quality.pdf?_tp=eyJjb250ZXh0Ijp7ImZpcnN0UGFnZSI6InB1YmxpY2F0aW9uIiwicGFnZSI6InB1YmxpY2F0aW9uIn19 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Khalifa, S.A.M.; Elashal, M.H.; Yosri, N.; Du, M.; Musharraf, S.G.; Nahar, L.; Sarker, S.D.; Guo, Z.; Cao, W.; Zou, X.; et al. Bee Pollen: Current Status and Therapeutic Potential. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algethami, J.S.; El-Wahed, A.A.A.; Elashal, M.H.; Ahmed, H.R.; Elshafiey, E.H.; Omar, E.M.; Al Naggar, Y.; Algethami, A.F.; Shou, Q.; Alsharif, S.M.; et al. Bee Pollen: Clinical Trials and Patent Applications. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Rasane, P.; Kumar, V.; Nanda, V.; Bhadariya, V.; Kaur, S.; Singh, J. Exploring the Health Benefits of Bee Pollen and Its Viability as a Functional Food Ingredient. Rev. Agric. Sci. 2024, 12, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisow, B.; Denisow-Pietrzyk, M. Biological and therapeutic properties of bee pollen: A review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4303–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Plutino, M.; Lucini, L.; Aromolo, R.; Martinelli, E.; Souto, E.B.; Santini, A.; Pignatti, G. Bee Products: A Representation of Biodiversity, Sustainability and Health. Life 2021, 11, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.M.S.; Camara, C.A.; da Silva Lins, A.C.; Barbosa-Filho, J.M.; da Silva, E.M.S.; Freitas, B.M.; dos Santos, F.D.A.R. Chemical composition and free radical scavenging activity of pollen loads from stingless bee Melipona subnitida Ducke. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga, C.; Martínez, A.; Fernández, J.; López-Baldó, J.; Quiles, A.; Rodrigo, D. Effect of high pressure processing on carotenoid and phenolic compounds, antioxidant capacity, and microbial counts of bee-pollen paste and bee-pollen-basedbeverage. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 37, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.-Q.; Wang, K.; Marcucci, M.C.; Sawaya, A.C.H.F.; Hu, L.; Xue, X.-F.; Wu, L.-M.; Hu, F.-L. Nutrient-rich bee pollen: A treasure trove of active natural metabolites. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 49, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, K.R.L.; Lins, A.C.S.; Dórea, M.C.; Santos, F.A.R.; Camara, C.A.; Silva, T.M.S. Palynological Origin, Phenolic Content, and Antioxidant Properties of Honeybee-Collected Pollen from Bahia, Brazil. Molecules 2012, 17, 1652–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leja, M.; Mareczek, A.; Wyzgolik, G.; Klepacz-Baniak, J.; Czekonska, K. Antioxidative properties of bee pollen in selected plant species. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, M.; Moreira, L.; Feás, X.; Estevinho, L.M. Honeybee-collected pollen from five Portuguese Natural Parks: Palynological origin, phenolic content, antioxidant properties and antimicrobial activity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aličić, D.; Šubarić, D.; Jašić, M.; Pašalić, H.; Ačkar, Đ. Antioxidant properties of pollen. Hrana Zdr. Boles. Znan.-Stručni Časopis Nutr. Dijetetiku 2014, 3, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Aylanc, V.; Falcao, S.I.; Ertosun, S.; Vilas-Boas, M. From the Hive to thesupp: Nutrition Value, Digestibility and Bioavailability of the Dietary Phytochemicals Present in the Bee Pollen and Bee Bread. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 109, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, K.; Moriya, M.; Azedo, R.; de Almeida-Muradian, L.B.; Teixeira, E.W.; Alves, M.L.T.M.F.; Moreti, A.C.d.C.C. Relationship between botanical origin and antioxidants vitamins of bee-collected pollen. Quim. Nova 2009, 5, 1099–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mărgăoan, R.; Mărghitas, L.A.; Dezmirean, D.S.; Dulf, F.V.; Bunea, A.; Socaci, S.A.; Bobiş, O. Predominant and secondary pollen botanical origins influence the caratenoid and fatty acid profile in fresh honeybee-collected pollen. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 6306–6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostić, A.Ž.; Barać, M.B.; Stanojević, S.P.; Milojković-Opsenica, D.M.; Tešić, Ž.L.; Šikoparija, B.; Radišić, P.; Prentović, M.; Pešić, M.B. Physicochemical composition and techno-functional properties of bee pollen collected in Serbia. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Muradian, L.B.; Pamplona, L.C.; Coimbra, S.; Barth, O.M. Chemical composition and botanical evaluation of dried bee pollen pellets. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2005, 18, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos Graça, M.; Frigerio, C.; Lopes, J.; Bogdanov, S. What is the future of bee pollen? J. ApiProduct ApiMedical Sci. 2010, 2, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauriello, G.; De Prisco, A.; Di Prisco, G.; La Storia, A.; Caprio, E. Microbial characterization of bee pollen from the Vesuvius area collected by using three different traps. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekki, I. Microbial Contamination of Bee Pollen and Impact of Preservation Methods. Master’s Thesis, Univeriste Libre de Tunis, Tunis, Tunisia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cabello, J.R.; Serrano, S.; Rodríguez, I.; García-Valcárcel, A.I.; Hernando, M.D.; Flores, J.M. Microbial decontamination of bee pollen by direct ozone exposure. Foods 2021, 10, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonvehí, J.S.; Jordà, R.E. Nutrient Composition and Microbiological Quality of Honeybee-Collected Pollen in Spain. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, R.G.; Linskens, H.F. Pollen: Biology Biochemistry Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1974; pp. 223–246. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Valhondo, D.; Bohoyo Gil, D.; Hernández, M.T.; González-Gómez, D. Influence of the commercial processing and floral origin on bioactive and nutritional properties of honeybee-collected pollen. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 2204–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas, J.; Cortes-Rodriguez, M.; Rodríguez-Sandoval, E. Effect of temperature on the drying process of bee pollen from two zones of colombia. J. Food Process Eng. 2012, 35, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Dong, Y.; Gu, C.; Zhang, X.; Ma, H. Processing Technologies for Bee Products: An Overview of Recent Developments and Perspectives. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 727181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevinho, L.M.; Dias, T.; Anjos, O. Influence of the storage conditions (frozen vs. dried) in health-related lipid indexes and antioxidants of bee pollen. Euro J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2018, 121, 1800393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yook, H.; Lim, S.; Byun, M. Changes in microbiological and physicochemical properties of bee pollen by application of gamma irradiation and ozone treatment. J. Food Prot. 1998, 61, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Naggar, Y.; Taha, I.M.; Taha, E.K.A.; Zaghlool, A.; Nasr, A.; Nagib, A.; Elhamamsy, S.M.; Abolaban, G.; Fahmy, A.; Hegazy, E.; et al. Gamma irradiation and ozone application as preservation methods for longer-term storage of bee pollen. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 25192–25201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.G.; Anjos, O.; Chica, M.; Campoy, P.; Nozkova, J.; Almaraz-Abarca, N.; Barreto, L.; Nordi, J.C.; Estevinho, L.; Pascoal, A.; et al. Standard methods for pollen research. J. Apic. Res. 2021, 60, 1–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varo, M.A.; Jacotet-Navarro, M.; Serratosa, M.P.; Mérida, J.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Bily, A.; Chemat, F. Green Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Antioxidant Phenolic Compounds Determined by High Performance Liquid Chromatography from Bilberry (Vaccinium Myrtillus L.) Juice By-Products. Waste Biomass Valorization 2018, 10, 1945–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katalinic, V.; Milos, M.; Kulisic, T.; Jukic, M. Screening of 70 Medicinal Plant Extracts for Antioxidant Capacity and Total Phenols. Food Chem. 2006, 94, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, S.; Escuredo, O.; Rodríguez-Flores, M.S.; Seijo, M.C. Botanical Origin of Galician Bee Pollen (Northwest Spain) for the Characterization of Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity. Foods 2023, 12, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardellach Lliso, P. Análisis Esporo-Polínico de la Miel y el Propóleo, y su Relación con el Entorno [Sporopollenin Analysis of Honey and Propolis, and Its Relationship with the Environment]. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2020. Available online: https://www.tesisenred.net/handle/10803/670125 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Boulfous, N.; Belattar, H.; Ambra, R.; Pastore, G.; Ghorab, A. Botanical origin, phytochemical profile, and antioxidant activity of bee pollen from the mila region, Algeria. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, J.F. Interpreting the magnitudes of correlation coefficients. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marghita¸s, L.A.; Stanciu, O.G.; Dezmirean, D.S.; Bobi¸s, O.; Popescu, O.; Bogdanov, S.; Campos, M.G. In vitro antioxidant capacity of honeybee-collected pollen of selected floral origin harvested from Romania. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 878–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, C.-I.; Oprea, E.; Geana, E.-I.; Spoiala, A.; Buleandra, M.; Gradisteanu Pircalabioru, G.; Badea, I.A.; Ficai, D.; Andronescu, E.; Ficai, A.; et al. Bee Pollen Extracts: Chemical Composition, Antioxidant Properties, and Effect on the Growth of Selected Probiotic and Pathogenic Bacteria. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghouizi, A.; Bakour, M.; Laaroussi, H.; Ousaaid, D.; El Menyiy, N.; Hano, C.; Lyoussi, B. Bee Pollen as Functional Food: Insights into Its Composition and Therapeutic Properties. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otmani, A.; Amessis-Ouchemoukh, N.; Birinci, C.; Yahiaoui, S.; Kolayli, S.; Rodríguez-Flores, M.S.; Ouchemoukh, S. Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of Algerian Honeys. Food Biosci. 2021, 42, 101070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbane, S.; Escuredo, O.; Saker, Y.; Ghorab, A.; Nakib, R.; Rodríguez-Flores, M.S.; Ouelhadj, A.; Seijo, M.C. The contribution of botanical origin to the physicochemical and antioxidant properties of Algerian honeys. Foods 2024, 13, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidi, H.; Ouchemoukh, S.; Amessis-Ouchemoukh, N.; Debbache, N.; Pacheco, R.; Serralheiro, M.L.; Araujo, M.E. Biological properties of phenolic compound extracts in selected Algerian honeys—The inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and α-glucosidase activities. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2019, 25, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J.S.; Chambó, E.D.; Costa, M.A.P.D.C.; Da Silva, S.M.P.C.; De Carvalho, C.A.L.; Estevinho, L.M. Chemical Composition and Biological Activities of Mono- and Heterofloral Bee Pollen of Different Geographical Origins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambaro, A.; Miraballes, M.; Urruzola, N.; Kniazev, M.; Dauber, C.; Romero, M.; Fernandez-Fernandez, A.M.; Medrano, A.; Santos, E.; Vieitez, I. Physicochemical Composition and Bioactive Properties of Uruguayan Bee Pollen from Different Botanical Sources. Foods 2025, 14, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuskoski, E.M.; Asuero, A.G.; Troncoso, A.M.; Mancini-Filho, J.; Fett, R. Aplicación de diversos métodos químicos para determinar actividad antioxidante en pulpa de frutos. Food Sci. Technol. 2005, 25, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, D.; Gabriele, M.; Summa, M.; Colosimo, R.; Leonardi, D.; Domenici, V.; Pucci, L. Antioxidant, nutraceutical properties, and fluorescence spectral profiles of bee pollen samples from different botanical origins. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, R.; Lu, Q. Separation and characterization of phenolamines and flavonoids from rape bee pollen, and comparison of their antioxidant activities and protective effects against oxidative stress. Molecules 2020, 25, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.V.; Rosa, C.I.L.F.; Vilas-Boas, E.V.B. Conceitos e metodos de controle do escurecimento enzim atico no processamento mínimo de frutas e hortaliças. Bol. CEPPA 2009, 27, 83e96. [Google Scholar]

- Castagna, A.; Benelli, G.; Conte, G.; Sgherri, C.; Signorini, F.; Nicolella, C.; Ranieri, A.; Canale, A. Drying Techniques and Storage: Do They Affect the Nutritional Value of Bee-Collected Pollen? Molecules 2020, 25, 4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachadyn-Król, M.; Agriopoulou, S. Ozonation as a Method of Abiotic Elicitation Improving the Health-Promoting Properties of Plant Products—A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, A.; Lahoucine, A.; Parvathi, K.; Chang-Jun, L.; Srinivasa, R.; Liangjiang, W. The phenylpropanoid pathway and plant defence-a genomics perspective. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2002, 1, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modesti, M.; Petriccione, M.; Forniti, R.; Zampella, L.; Scortichini, M.; Mencarelli, F. Methyl jasmonate and ozone affect the antioxidant system and the quality of wine grape during postharvest partial dehydration. Food Res. Int. 2018, 112, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga-Domíngueza, C.; Serrato-Bermudez, J.; Quicazán, M. Influence of drying-related operations on microbiological, structural and physicochemical aspects for processing of bee-pollen. Eng. Agric. Environ. Food 2018, 11, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.P. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS for Windows: Advanced Techniques for the Beginner; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.T.E. Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educ. Res. Rev. 2011, 6, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Code | Total Phenolic Compounds | Antioxidant Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh bee pollen (Control) | C | 1121 ± 351 a | 2.82 ± 0.82 a |

| Drying 4 h | D4 | 1000 ± 361 b | 3.28 ± 1.12 b |

| Drying 8 h | D8 | 1011 ± 351 b | 3.30 ± 1.15 b |

| Ozone 1 h | O1 | 1119 ± 367 a | 2.81 ± 0.89 a |

| Ozone 2 h | O2 | 1216 ± 392 a | 2.79 ± 0.90 a |

| Treatment | Sample | |

|---|---|---|

| mg gallic acid/100 g dry bee pollen | 0.22 | 2.65 |

| mg Trolox/100 g dry bee pollen | 0.24 | 0.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muñoz-Vílchez, P.; Bohoyo-Gil, D.; López-Orozco, R.; Moyano, L.; Flores, J.M.; Varo, M.Á. Effect of Ozone and Drying Treatments on Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Bee Pollen. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13175. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413175

Muñoz-Vílchez P, Bohoyo-Gil D, López-Orozco R, Moyano L, Flores JM, Varo MÁ. Effect of Ozone and Drying Treatments on Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Bee Pollen. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13175. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413175

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuñoz-Vílchez, Purificación, Diego Bohoyo-Gil, Rocío López-Orozco, Lourdes Moyano, José Manuel Flores, and María Ángeles Varo. 2025. "Effect of Ozone and Drying Treatments on Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Bee Pollen" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13175. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413175

APA StyleMuñoz-Vílchez, P., Bohoyo-Gil, D., López-Orozco, R., Moyano, L., Flores, J. M., & Varo, M. Á. (2025). Effect of Ozone and Drying Treatments on Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Bee Pollen. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13175. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413175