Electrical Parameters as a Tool for Evaluating the Quality and Functional Properties of Superfruit Purees

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

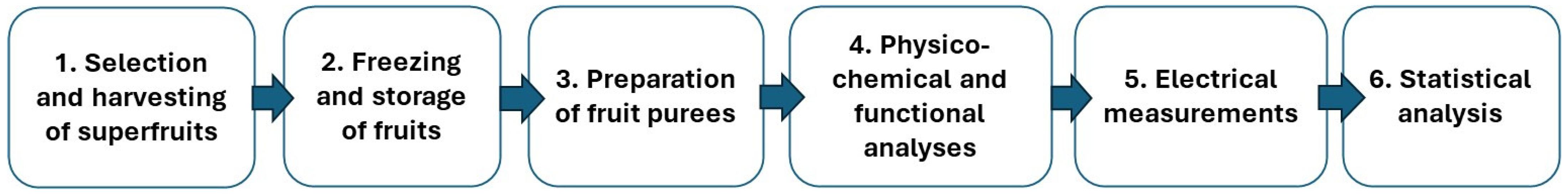

- To assess differences in technological traits and functional properties of purees from 12 superfruit species using conventional physicochemical and functional reference analyses.

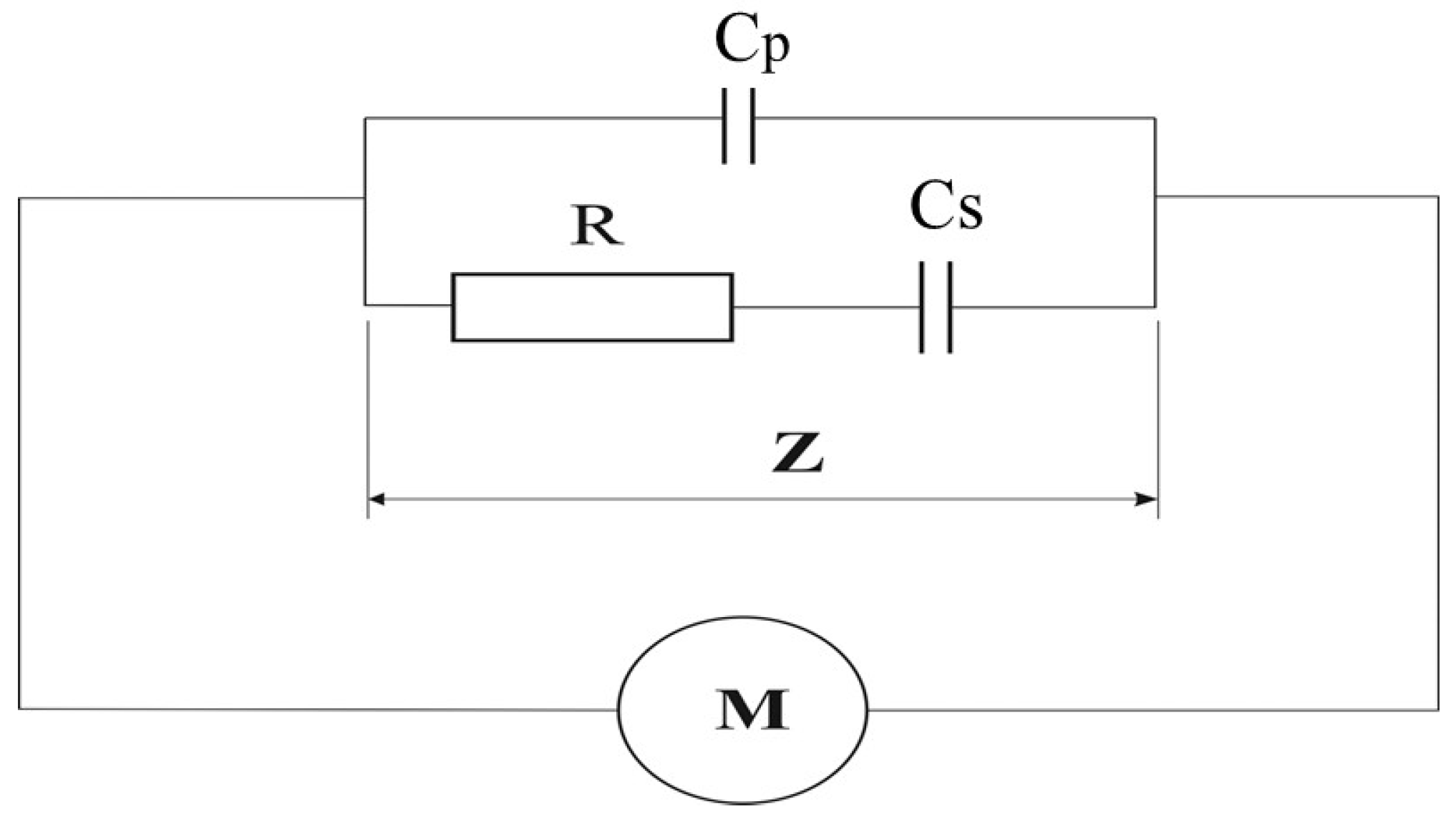

- To determine the electrical profile of fruit purees using the RCC equivalent circuit model.

- To identify statistical correlations between electrical parameters and the technological traits and functional properties of the investigated purees.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Physicochemical Analyses

2.1.1. Dry Matter, Ash, Protein and Fat Content

2.1.2. Total Extract Content

2.1.3. Total Acidity

- V—volume of NaOH solution used for the titration of the solution, mL

- N—NaOH molarity, mol/dm3

- V0—total volume of solution used to dilute and supplement the sample to a defined volume, mL

- V1—volume of filtrate sample taken for titration, mL

- m—mass of sample, g

- K—factor used to convert the corresponding acid in individual products:

- K = 0.064—citric acid in products from berries and citrus; N = 0.1 mol/dm3; V0 = 250 mL;

- V1 = 5 mL; m = 25 g.

2.1.4. Preparation of Extract and Determination of Total Polyphenol Content and Radical Scavenging Activity

2.1.5. Total Flavonoid Content

2.1.6. Total Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C) Content

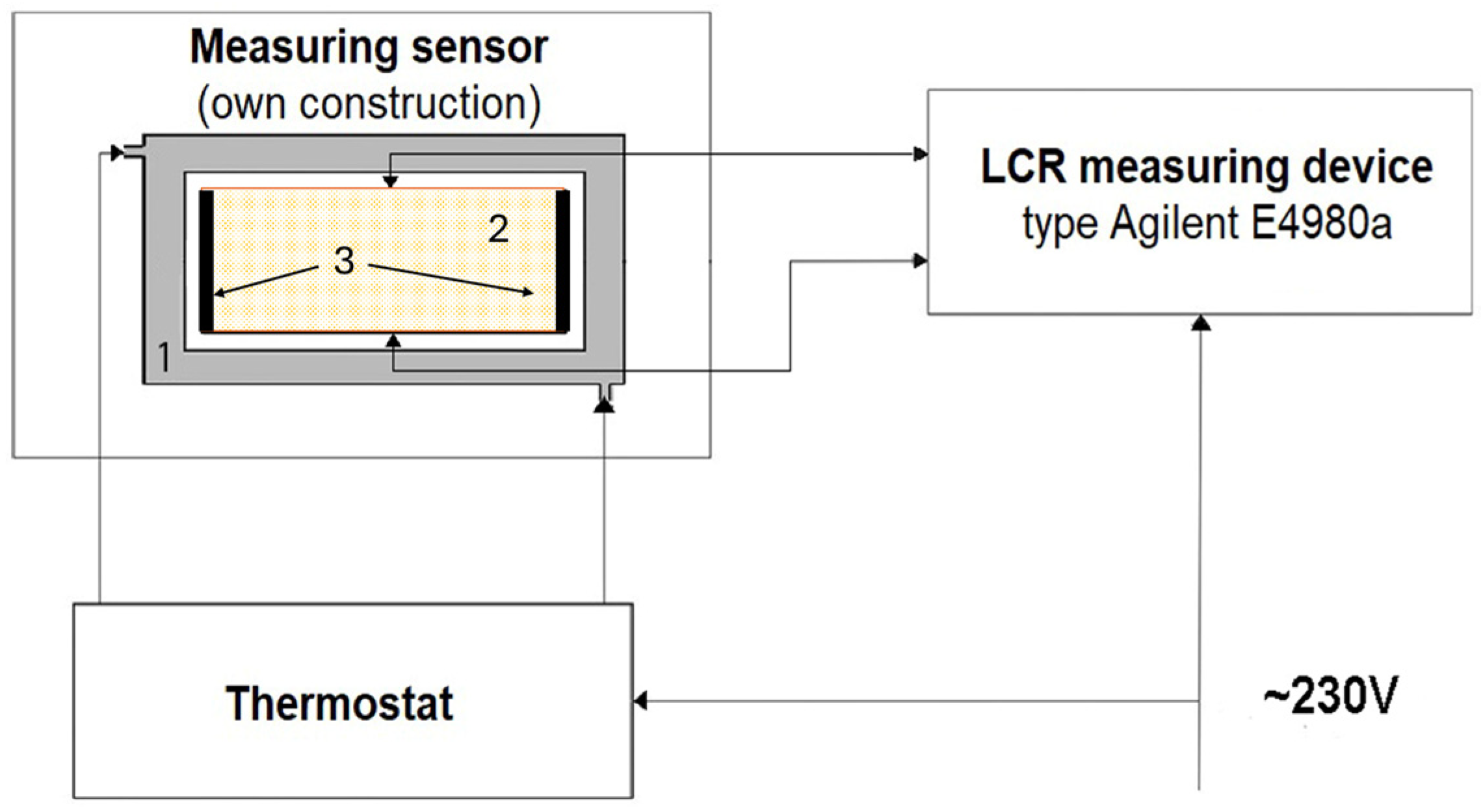

2.2. Electrical Measurements

- A sensor—a glass cell with two stainless steel plate electrodes mounted on the smaller inner walls of the container (own construction),

- An LCR meter, type E4980a (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

- A metal container with a water jacket connected to a thermostat (PolyScience, Niles, IL, USA),

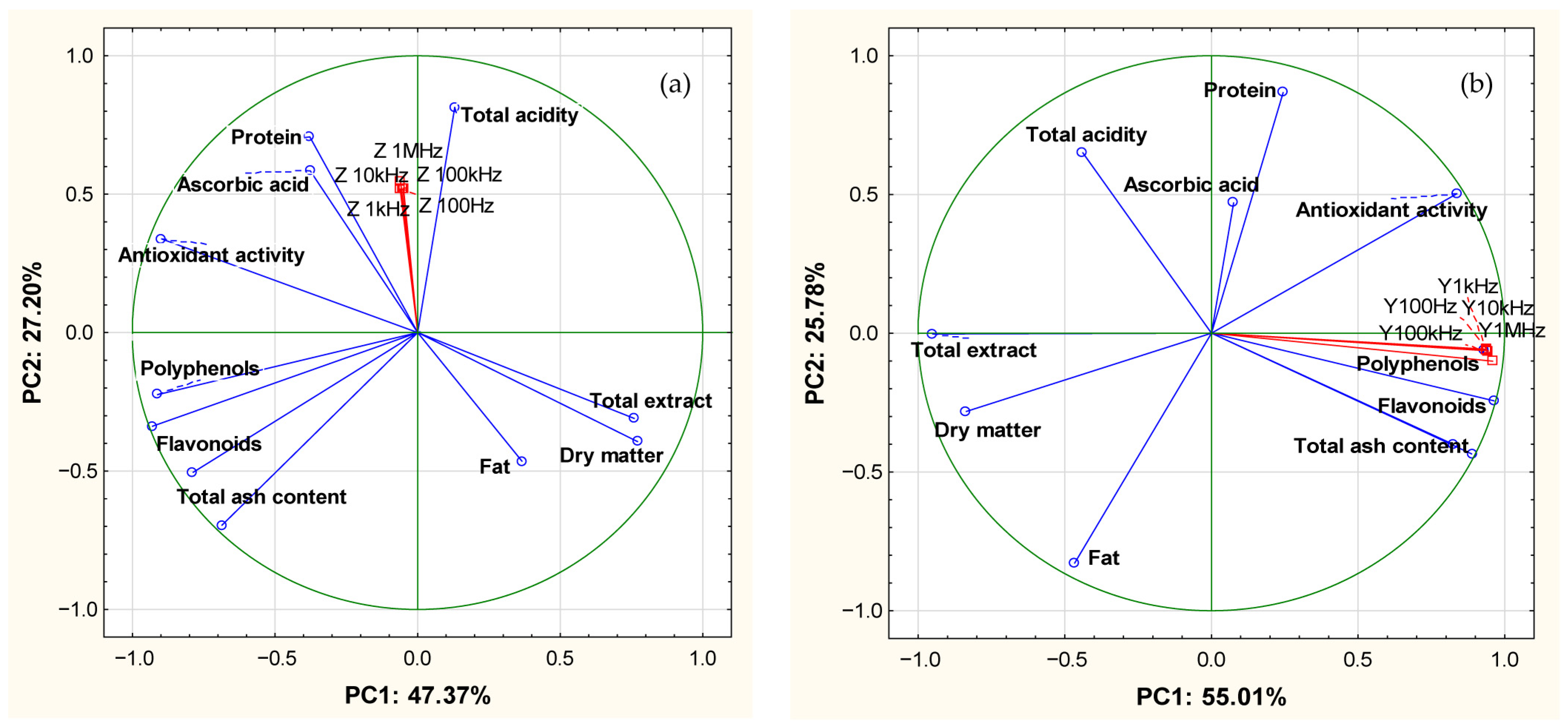

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Analysis

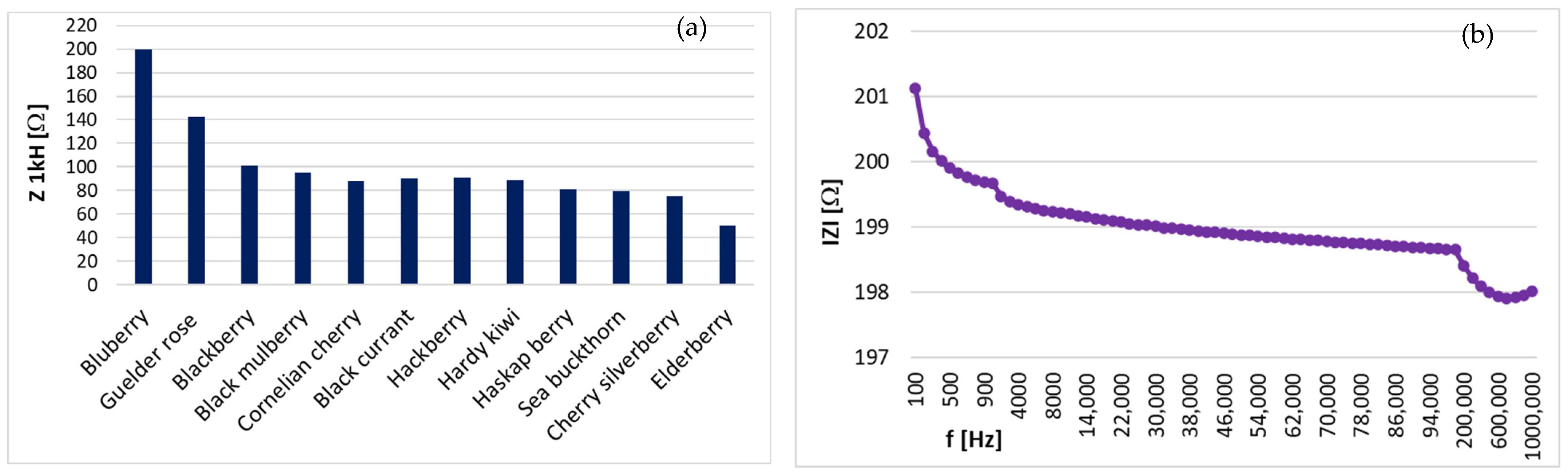

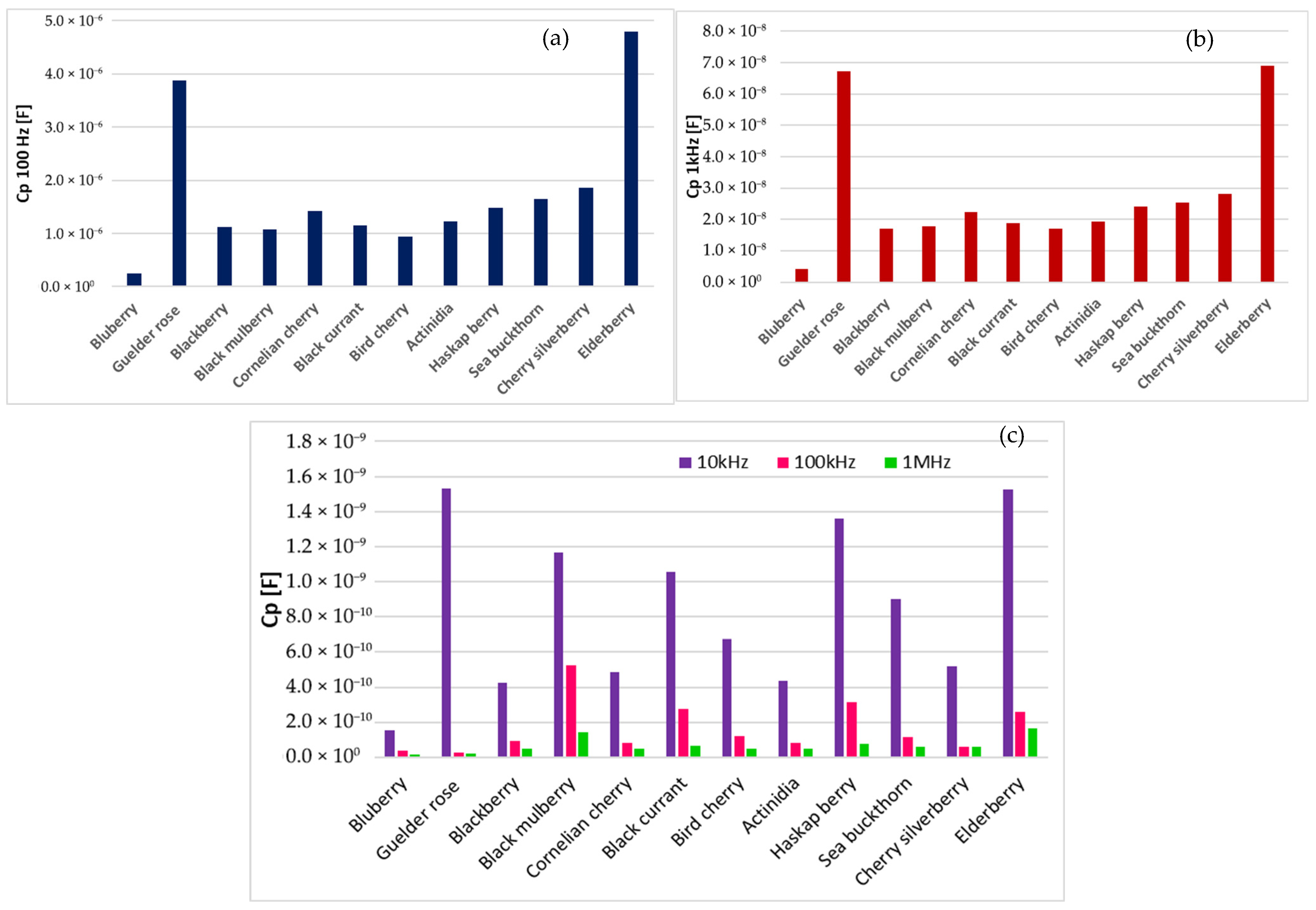

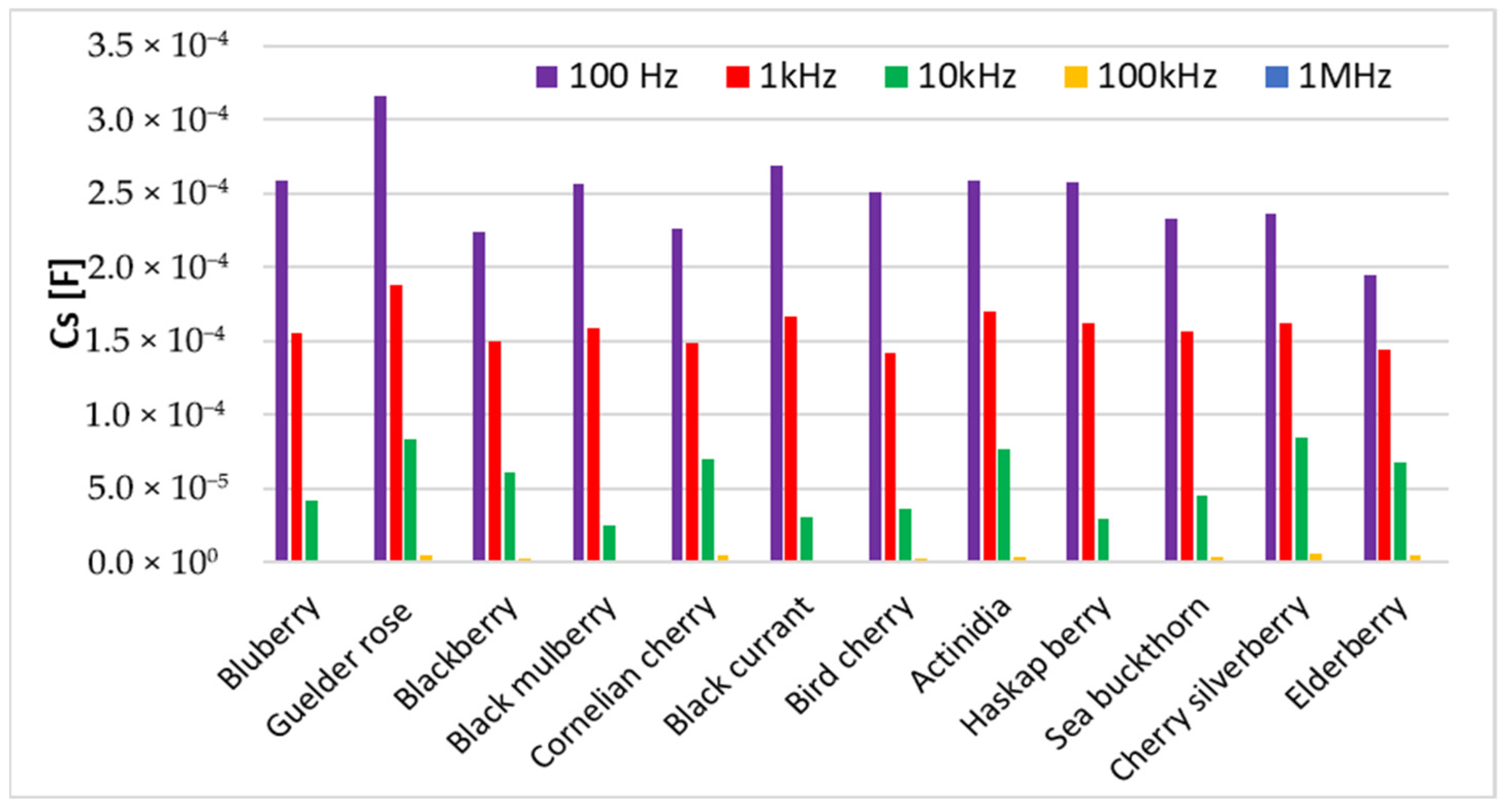

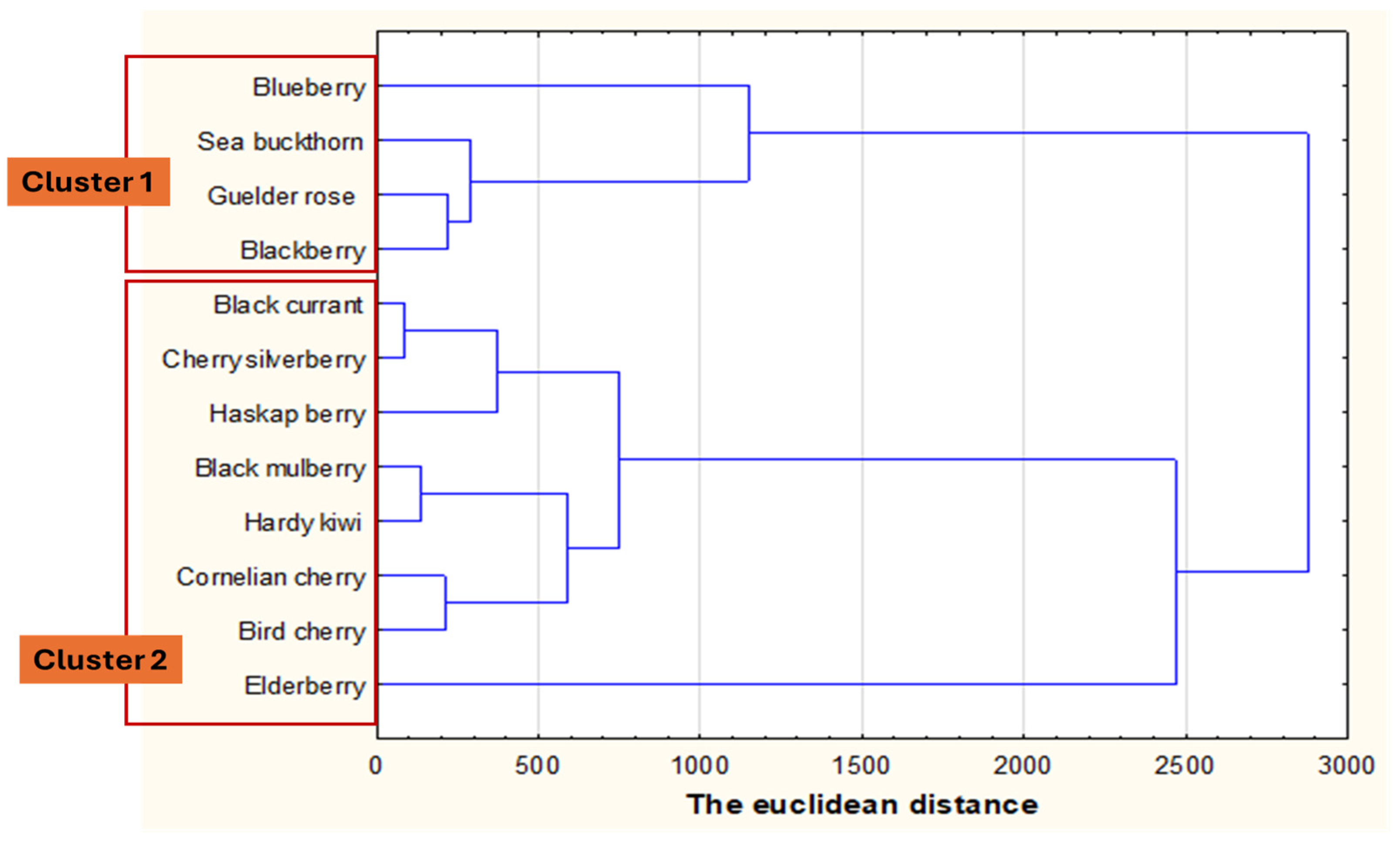

3.2. Electrical Characterization

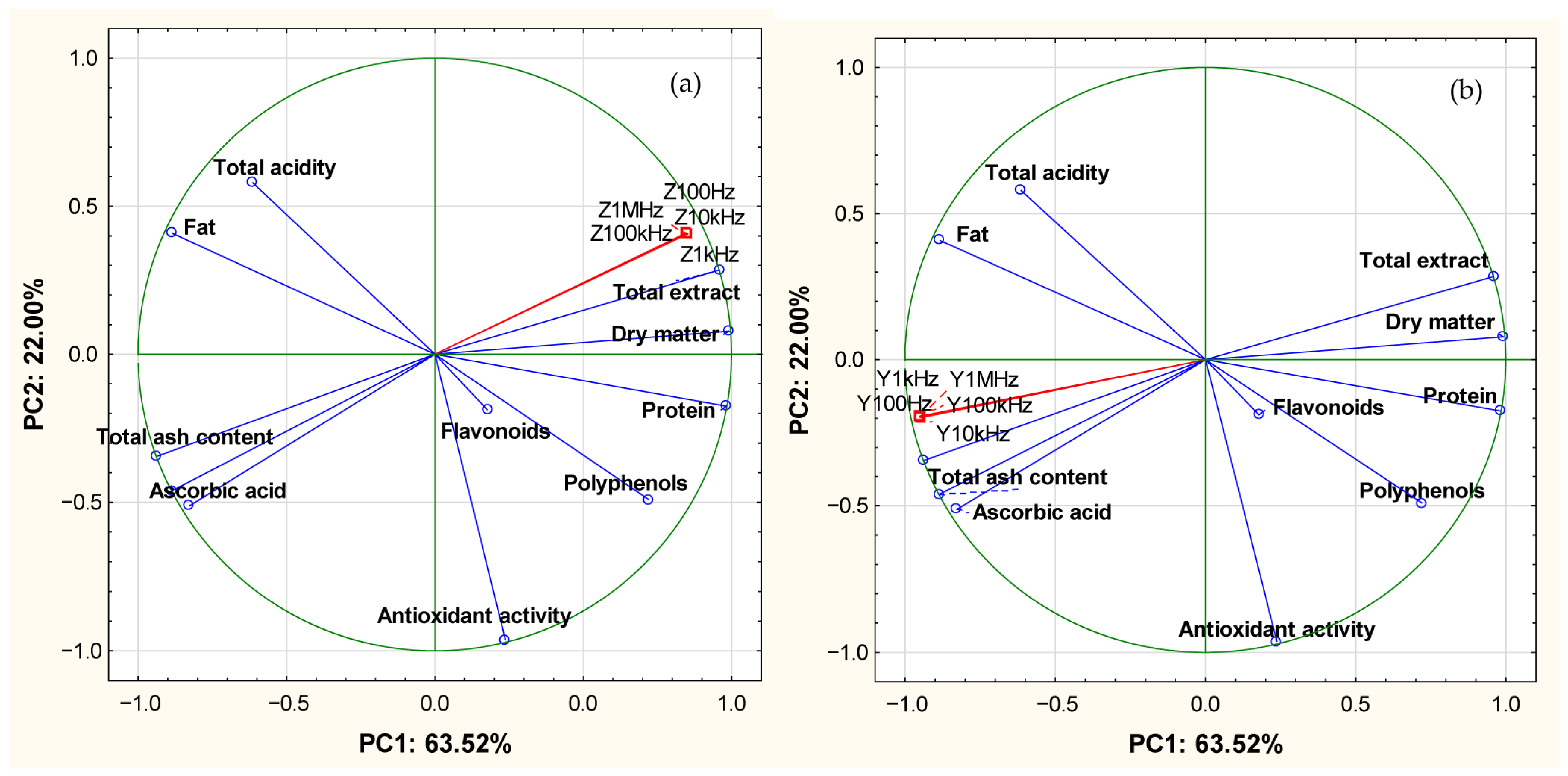

3.3. Correlations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bieniek, A.; Lachowicz-Wiśniewska, S.; Bojarska, J. The Bioactive Profile. Nutritional Value. Health Benefits and Agronomic Requirements of Cherry Silverberry (Elaeagnus multiflora Thunb.): A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa, T.; Klimek, K.; Zara’s-Januszkiewicz, E. Nutritional Values of Minikiwi Fruit (Actinidia arguta) after Storage: Comparison between DCA New Technology and ULO and CA. Molecules 2022, 27, 4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latocha, P. The Nutritional and Health Benefits of Kiwiberry (Actinidia arguta)—A Review. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2017, 72, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szot, I.; Łysiak, G.P.; Sosnowska, B. The Beneficial Effects of Anthocyanins from Cornelian Cherry (Cornus mas L.) Fruits and Their Possible Uses: A Review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żyżelewicz, D.; Oracz, J. Bioavailability and Bioactivity of Plant Antioxidants. Antioxidant 2022, 11, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrovankova, S.; Sumczynski, D.; Mlcek, J.; Jurikova, T.; Sochor, J. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in different types of berries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 24673–24706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.K.; Alasalvar, C.; Shahidi, F. Superfruits: Phytochemicals. antioxidant efficacies. and health effects—A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 1580–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Kortesniemi, M. Clinical evidence on potential health benefits of berries. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 2, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Galli, M.; Adamska-Patruno, E.; Krętowski, A.; Ciborowski, M. Select polyphenol-rich berry consumption to defer or deter diabets-related complications. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.; Gonzalez de Mejia, E. Phenolic composition. antioxidant capacity and physical characterization of ten blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) cultivars. their juices. and the inhibition of type 2 diabetes and inflammation biochemical markers. Food Chem. 2021, 359, 129889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, J.M. Berries as Foods: Processing. Products. and Health Implications. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 15, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saarniit, K.; Lang, H.; Kuldjärv, R.; Laaksonen, O.; Rosenvald, S. The stability of phenolic compounds in fruit. berry. and vegetable purees based on accelerated shelf-life testing methodology. Foods 2023, 12, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, H. Non-Destructive Detection of Fruit Quality: Technologies. Applications and Prospects. Foods 2025, 14, 2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banach, J.K.; Żywica, R. A Method of Evaluating Apple Juice Adulteration with Sucrose Based on Its Electrical Properties and RCC Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Feng, L.; Yun, F.; Sui, X.; Gao, J. Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy in Agricultural Food Quality Detection. J. Food Process Eng. 2025, 48, e70085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khaled, D.; Castellano, N.N.; Gazquez, J.A.; Salvador, R.G.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Cleaner quality control system using bioimpedance methods: A review for fruits and vegetables. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 40, 1749–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.; Abu Izneid, B.A.; Abdullah, M.Z.; Arshad, M.R. Assessment of quality of fruits using impedance spectroscopy. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xia, Y.; Che, J.; Lan, H.; Zhang, H. Detection method for the degree of damage to Korla fragrant pears based on electrical properties. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2025, 18, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, P.P.; Walsh, K.B. Non-invasive techniques for measurement of fresh fruit quality. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2009, 69, 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Ibba, P.; Falco, A.; Abera, B.D.; Cantarella, G.; Petti, L.; Lugli, P. Bio-impedance and circuit parameters: An analysis for tracking fruit ripening. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 159, 110978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makroo, H.A.; Prabhakar, P.K.; Rastogi, N.K.; Srivastava, B. Characterization of mango puree based on total soluble solids and acid content: Effect on physico-chemical, rheological, thermal and ohmic heating behavior. LWT 2019, 103, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardinasinta, G. Effect of ohmic heating on the rheological characteristics of mulberry puree. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2021, 71, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, X.; Shen, L.; Gao, M. Analysis of microwave heating uniformity in berry puree: From electromagnetic-wave dissipation to heat and mass transfer. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 90, 103509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Morales, M.E.; Flores-López, T.; Miranda-Estrada, D.E.; Kaur Kataria, T.; Abraham-Juárez, M.D.R.; Cerón-García, A.; Corona-Chávez, A.; Olvera-Cervantes, J.L.; Rojas-Laguna, R. Dielectric properties of berries in the microwave range at variable temperature. J. Berry Res. 2017, 7, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Haeverbeke, M.; De Baets, B.; Stock, M. Plant impedance spectroscopy: A review of modeling approaches and applications. Front. Plant Methods 2023, 14, 1187573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AACC Methods, 8th ed.; American Association of Cereal Chemists: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1996.

- Mæhre, H.K.; Dalheim, L.; Edvinsen, G.K.; Elvevoll, E.O.; Jensen, I.J. Protein Determination-Method Matters. Foods 2018, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M. Measuring Protein Content in Food: An Overview of Methods. Foods 2020, 9, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-90/A-75101/02; Przetwory Owocowe i Warzywne. Przygotowanie Próbek i Metody Badań Fizykochemicznych. Oznaczenie Zawartości Ekstraktu Ogólnego. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny: Warszawa, Poland, 1990. (In Polish)

- PN-90/A-75101/04; Przetwory Owocowe i Warzywne. Przygotowanie Próbek i Metody Badań Fizykochemicznych. Oznaczenie Kwasowości Ogólnej. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny: Warszawa, Poland, 1990. (In Polish)

- Singleton, V.L.; Ross, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchés-Moreno, C.; Larrauri, A.; Saura-Calixto, F. A procedure to measure the antioxidant afficiency of polyphenols. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1998, 76, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willet, W.C. Balancing lifestyle and genomic research for disease prevention. Science 2002, 292, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, B.P.; Perry, A.K. Ascorbic acid and vitamin A activity in selected vegetables from different geographical areas of the united sates. J. Food Sci. 1982, 47, 941–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żywica, R.; Banach, J.K. Correlations between selected quality and electrical parameters of musts from stone and pome fruits. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 13, 1508–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żywica, R.; Banach, J.K. Method of Predicting TSS Content in Fruit Juices, Especially Apple Juice. Patent of the Polish Republic No. 395911, 2 June 2016. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Żywica, R.; Banach, J.K. Simple linear correlation between concentration and electrical properties of apple juice. J. Food Eng. 2015, 158, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, J.; van Rienen, U. Ambiguity in the Interpretation of the Low-Frequency Dielectric Properties of Biological Tissues. Bioelectrochemistry 2021, 140, 107773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazanas, A.C.; Prodromidis, M.I. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy—A Tutorial. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2023, 3, 162–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massart, D.L.; Vander Heyden, Y. From tables to visuals: Principal component analysis. part 1. LC-GC Eur. 2004, 17, 586–591. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar]

- Bąk, A. Analiza porównawcza wybranych metod porządkowania liniowego. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2018, 508, 19–28. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Nardozza, S.; Gamble, J.; Axten, L.G.; Wohlers, M.W.; Clearwater, M.J.; Feng, J.; Harker, F.R. Dry matter content and fruit size affect flavour and texture of novel Actinidia deliciosa genotypes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisosto, G.M.; Hasey, J.; Zegbe, J.A.; Crisosto, C.H. New quality index based on dry matter and acidity proposed for ‘Hayward’ kiwifruit. Calif. Agric. 2012, 66, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donno, D.; Mellano, M.G.; De Biaggi, M.; Riondato, I.; Rakotoniaina, E.N.; Beccaro, G.L. New Findings in Prunus padus L. Fruits as a Source of Natural Compounds: Characterization of Metabolite Profiles and Preliminary Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity. Molecules 2018, 23, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins-Veazie, P.; Thomas, A.L.; Byers, P.L.; Finn, C.E. Fruit composition of elderberry (Sambucus spp.) genotypes grown in Oregon and Missouri. USA. Acta Hortic. 2015, 1061, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, R.K.; Shukla, S.; Shukla, V.; Singh, S. Sea buckthorn: A potential dietary suplement with multifaceted therapeutic activities. Intell. Pharm. 2024, 2, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsinach, M.S.; Cuenca, A.P. The impact of sea buckthorn oil fatty acids on human health. Lipids Health Dis. 2019, 18, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas-Franquesa, A.; Saldo, J.; Juan, B. Potential of sea buckthorn-based ingredients for the food and feed industry—A review. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2020, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costica, N. Characteristics of elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) fruit. Acta Agric. Silvic. Croat. 2019, 6, 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, C.P.; Almeida, A.A.; Comunian, T.A.; Alves, R.C.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Sustainable Valorization of Sambucus nigra L. Berries. Foods 2021, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telichowska, A.; Kobus-Cisowska, J.; Szulc, P.; Cielecka-Piontek, J.; Sip, S.; Stuper-Szablewska, K.; Szulc, P. Prunus padus L. as a source of functional compounds—Antioxidant activity and antidiabetic effect. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icier, F.; Ilicali, C. Temperature-dependent electrical conductivities of fruit purees during ohmic heating. Food Res. Int. 2005, 38, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khaled, D.; Novas, N.; Gázquez, J.A.; García, R.M.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Fruit and vegetable quality assessment via dielectric sensing. Sensors 2015, 15, 15363–15397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Madrera, R.; Pando Bedriñana, R. The Phenolic Composition. Antioxidant Activity and Microflora of Wild Elderberry in Asturias (Northern Spain): An Untapped Resource of Great Interest. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dienaitė, L.; Pukalskienė, M.; Pereira, C.V.; Matias, A.A.; Venskutonis, P.R. Valorization of European Cranberry Bush (Viburnum opulus L.) Berry Pomace Extracts Isolated with Pressurized Ethanol and Water by Assessing Their Phytochemical Composition. Antioxidant. and Antiproliferative Activities. Foods 2020, 9, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Wang, B.; Huang, Z.; Lv, J.; Teng, Y.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, K.; Qin, D.; Huo, J.; et al. Evaluation of Blue Honeysuckle Berries (Lonicera caerulea L.) Dried at Different Temperatures: Basic Quality. Sensory Attributes. Bioactive Compounds. and In Vitro Antioxidant Activity. Foods 2024, 13, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajszczak, D.; Kowalska-Baron, A.; Podsędek, A. Glycoside hydrolases and non-enzymatic glycation inhibitory potential of Viburnum opulus L. fruit—In Vitro Studies. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaume, L.; Howard, L.R.; Devareddy, L. The Blackberry Fruit: A Review on its Composition and Chemistry. Metabolism and Bioavailability. and Health Benefits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 5716–5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christaki, E. Hippophae rhamnoides L. (sea buckthorn): A potential source of nutraceuticals. Food Public Health 2012, 2, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, L.T.; Silva, A.S.; Toscano, L.T.; Tavares, R.L.; Biasoto, A.C.T.; Costa de Camargo, A.; da Silva, C.S.O.; da Conceição Rodrigues Gonçalves, M.; Shahidi, F. Phenolics from purple grape juice increase serum antioxidant status and improve lipid profile and blood pressure in healthy adults under intense physical training. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 33, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabjanowicz, M.; Różańska, A.; Abdelwahab, N.S.; Pereira-Coelho, M.; da Silva Haas, I.V.; dos Santos Madureira, L.A.; Płotka-Wasylka, J. An analytical approach to determine the health benefits and health risks of consuming berry juices. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 137219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berni, P.; Araujo, N.M.P.; Zandoná, L.R.; Morzelle, M.C.; da Silva Lucas, A.J.; Maróstica Junior, M.R. Chapter 9-Brazilian berries: The superfruits we need for the future. Improv. Health Nutr. Funct. Foods 2025, 173–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abasi, S.; Sadeghi, M.; Parhizgar, S.S.; Ghasemi, A.; Rashedi, H.; Akbari, M. Bioelectrical impedance spectroscopy for monitoring biological systems. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2022, 2, 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsoukov, E.; Macdonald, J.R. Impedance Spectroscopy: Theory: Experiment. and Applications, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Repo, T.; Korhonen, A.; Laukkanen, M.; Silvennoinen, R. Detecting freezing injury of scots pine roots using electrical impedance spectroscopy. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2013, 96, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, W.J.; Wei, X.H.; Sun, H.W. Maturity assessment of tomato fruit based on electrical impedance spectroscopy. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2019, 12, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patras, A.; Brunton, N.P.; Downey, G.; Rawson, A.; Warriner, K.; Gernigon, G. Application of principal component and hierarchical cluster analysis to classify fruits and vegetables commonly consumed in Ireland based on in vitro antioxidant activity. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fruit Purees | Dry Matter (%) | Protein (%) | Fat (%) | Total Extract (%) | Total Acidity (%) | Total Ash (%) | Polyphenols (mg GAE/g d.m.) | Flavonoids (mg QE/g d.m.) | Antioxidant Activity (mg TEAC/g d.m.) | Ascorbic Acid (mg/g d.m.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blueberry | 13.766 a | 2.510 b | 0.336 ab | 12.25 de | 1.304 c | 0.136 d | 35.206 bc | 6.525 c | 46.201 a | 11.677 a |

| Elderberry | 10.513 c | 2.175 g | 0.285 ab | 9.00 b | 0.798 a | 0.865 f | 94.081 e | 51.169 f | 73.158 i | 12.234 ad |

| Sea buckthorn | 10.916 c | 1.195 a | 2.486 d | 9.50 bc | 3.001 b | 0.314 b | 26.700 abc | 11.375 e | 41.326 g | 16.826 b |

| Guelder rose | 14.224 ab | 2.880 i | 0.163 a | 12.00 d | 1.624 e | 0.170 d | 59.541 d | 17.146 d | 57.998 c | 14.047 e |

| Blackberry | 11.952 e | 2.065 f | 0.410 ab | 10.00 c | 0.821 a | 0.322 b | 41.559 cd | 8.665 ce | 69.664 h | 16.669 b |

| Black currant | 14.282 b | 1.930 e | 0.220 ab | 12.75 ef | 2.989 b | 0.413 ab | 34.627 abc | 0.284 a | 52.676 b | 9.890 c |

| Black mulberry | 14.008 ab | 0.875 c | 0.507 b | 13.00 a | 0.866 a | 0.558 ce | 19.674 ab | 2.909 ab | 34.481 f | 11.571 a |

| Haskap berry | 15.802 d | 2.462 b | 0.357 ab | 13.50 a | 2.658 h | 0.467 ac | 44.279 cd | 15.244 d | 46.466 a | 10.939 ac |

| Hardy kiwi | 18.905 g | 1.125 a | 0.851 c | 15.25 g | 1.527 d | 0.478 ac | 15.598 a | 14.968 d | 24.852 d | 11.397 a |

| Cornelian cherry | 15.620 d | 2.995 j | 0.257 ab | 14.75 g | 1.938 f | 0.472 ac | 31.235 abc | 2.199 ab | 57.278 c | 13.697 de |

| Cherry silverberry | 12.713 f | 2.700 h | 0.254 ab | 13.00 af | 2.016 g | 0.408 ab | 15.993 ab | 0.561 a | 50.250 b | 16.376 b |

| Bird cherry | 25.542 h | 1.675 d | 0.291 ab | 24.50 h | 0.855 a | 0.586 e | 20.567 ab | 5.396 bc | 30.165 e | 7.527 f |

| Parameters | |Z| | |Y| | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 Hz | 1 kHz | 10 kHz | 100 kHz | 1 MHz | 100 Hz | 1 kHz | 10 kHz | 100 kHz | 1 MHz | |

| Dry matter | 0.834 * | 0.834 * | 0.835 * | 0.836 * | 0.840 * | −0.929 ** | −0.929 ** | −0.930 ** | −0.930 ** | −0.933 ** |

| Protein | 0.738 | 0.737 | 0.738 | 0.740 | 0.743 | −0.881 * | −0.881 * | −0.882 * | −0.883 * | −0.884 * |

| Fat | −0.659 | −0.658 | −0.659 | −0.661 | −0.661 | 0.815 * | 0.813 * | 0.815 * | 0.817 * | 0.815 * |

| Total extract | 0.927 ** | 0.927 ** | 0.927 ** | 0.928 ** | 0.931 ** | −0.964 ** | −0.965 ** | −0.965 ** | −0.965 ** | −0.967 ** |

| Total acidity | −0.467 | −0.465 | −0.466 | −0.467 | −0.465 | 0.602 | 0.600 | 0.602 | 0.603 | 0.598 |

| Total ash | −0.931 ** | −0.931 ** | −0.931 ** | −0.932 ** | −0.935 ** | 0.926 ** | 0.927 ** | 0.926 ** | 0.926 ** | 0.928 ** |

| Polyphenol | 0.243 | 0.243 | 0.244 | 0.247 | 0.253 | −0.466 | −0.466 | −0.469 | −0.471 | −0.473 |

| Flavonoids | −0.256 | −0.256 | −0.255 | −0.252 | −0.245 | 0.108 | 0.106 | 0.105 | 0.103 | 0.097 |

| Antioxidant activity | −0.148 | −0.150 | −0.149 | −0.147 | −0.148 | −0.068 | −0.065 | −0.069 | −0.070 | −0.067 |

| Vitamin C | −0.988 ** | −0.988 ** | −0.988 ** | −0.988 ** | −0.989 ** | 0.942 ** | 0.943 ** | 0.942 ** | 0.941 ** | 0.942 ** |

| Cp | Cs | |||||||||

| Dry matter | −0.977 ** | −0.972 ** | −0.949 ** | −0.997 ** | −0.989 ** | 0.726 | 0.477 | 0.451 | −0.006 | −0.513 |

| Protein | −0.932 ** | −0.931 ** | −0.977 ** | −0.946 ** | −0.936 ** | 0.642 | 0.419 | 0.570 | 0.017 | −0.482 |

| Fat | 0.826 * | 0.834 * | 0.951 ** | 0.777 | 0.800 * | −0.320 | −0.099 | −0.469 | 0.196 | 0.597 |

| Total extract | −0.987 ** | −0.983 ** | −0.906 ** | −0.982 ** | −0.994 ** | 0.665 | 0.382 | 0.243 | −0.155 | −0.623 |

| Total acidity | 0.562 | 0.580 | 0.750 | 0.446 | 0.506 | 0.117 | 0.301 | −0.244 | 0.429 | 0.642 |

| Total ash | 0.942 ** | 0.937 ** | 0.811 * | 0.941 * | 0.954 ** | −0.668 | −0.386 | −0.122 | 0.172 | 0.605 |

| Polyphenol | −0.587 | −0.578 | −0.700 | −0.699 | −0.622 | 0.734 | 0.691 | 0.933 ** | 0.527 | 0.072 |

| Flavonoids | −0.058 | −0.035 | −0.063 | −0.275 | −0.138 | 0.802 * | 0.948 ** | 0.846 * | 0.962 ** | 0.691 |

| Antioxidant activity | −0.094 | −0.105 | −0.369 | −0.075 | −0.066 | −0.121 | −0.089 | 0.590 | 0.096 | −0.015 |

| Vitamin C | 0.915 ** | 0.915 ** | 0.782 | 0.856 * | 0.906 ** | −0.450 | −0.132 | 0.106 | 0.424 | 0.780 |

| Parameters | |Z| | |Y| | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 Hz | 1 kHz | 10 kHz | 100 kHz | 1 MHz | 100 Hz | 1 kHz | 10 kHz | 100 kHz | 1 MHz | |

| Dry matter | 0.695 | 0.694 | 0.695 | 0.706 | 0.759 | −0.713 | −0.712 | −0.713 | −0.717 | −0.741 |

| Protein | −0.354 | −0.356 | −0.356 | −0.345 | −0.263 | 0.259 | 0.258 | 0.257 | 0.251 | 0.201 |

| Fat | 0.331 | 0.331 | 0.333 | 0.341 | 0.340 | −0.295 | −0.294 | −0.295 | −0.299 | −0.295 |

| Total extract | 0.861 * | 0.860 * | 0.861 * | 0.874 * | 0.916 ** | −0.895 * | −0.895 * | −0.895 * | −0.902 ** | −0.922 ** |

| Total acidity | 0.338 | 0.342 | 0.340 | 0.337 | 0.402 | −0.430 | −0.434 | −0.433 | −0.430 | −0.465 |

| Total ash | −0.769 | −0.771 | −0.771 | −0.778 | −0.828 * | 0.851 * | 0.854 * | 0.855 * | 0.859 | 0.886 * |

| Polyphenol | −0.846 * | −0.847 * | −0.849 * | −0.859 * | −0.875 * | 0.886 * | 0.888 | 0.889 * | 0.895 * | 0.904 ** |

| Flavonoids | −0.860 * | −0.861 * | −0.861 * | −0.865 * | −0.873 * | 0.902 ** | 0.903 ** | 0.903 ** | 0.906 ** | 0.910 ** |

| Antioxidant activity | −0.738 | −0.740 | −0.741 | −0.743 | −0.729 | 0.737 | 0.738 | 0.739 | 0.739 | 0.728 |

| Vitamin C | −0.251 | −0.253 | −0.251 | −0.230 | −0.182 | 0.175 | 0.174 | 0.172 | 0.157 | 0.121 |

| Cp | Cs | |||||||||

| Dry matter | −0.715 | −0.717 | −0.546 | −0.255 | −0.668 | 0.843 * | 0.817 * | −0.014 | −0.142 | 0.028 |

| Protein | 0.221 | 0.227 | −0.124 | −0.535 | −0.355 | −0.440 | −0.448 | 0.355 | 0.488 | 0.649 |

| Fat | −0.280 | −0.290 | −0.302 | −0.020 | −0.096 | 0.351 | 0.483 | 0.117 | −0.058 | −0.121 |

| Total extract | −0.893 * | −0.897 * | −0.725 | −0.262 | −0.746 | 0.761 | 0.762 | 0.008 | −0.054 | −0.019 |

| Total acidity | −0.496 | −0.486 | −0.138 | −0.228 | −0.696 | 0.553 | 0.491 | −0.257 | −0.172 | 0.202 |

| Total ash | 0.896 * | 0.897 * | 0.619 | 0.276 | 0.843 * | −0.766 | −0.708 | 0.088 | 0.040 | −0.072 |

| Polyphenol | 0.898 * | 0.908 * | 0.732 | 0.168 | 0.638 | −0.716 | −0.686 | −0.017 | −0.011 | 0.102 |

| Flavonoids | 0.910 ** | 0.912 ** | 0.580 | 0.065 | 0.629 | −0.702 | −0.539 | 0.194 | 0.139 | 0.186 |

| Antioxidant activity | 0.744 | 0.751 | 0.428 | −0.095 | 0.347 | −0.760 | −0.776 | 0.148 | 0.244 | 0.308 |

| Vitamin C | 0.152 | 0.139 | −0.508 | −0.559 | −0.203 | −0.464 | −0.302 | 0.729 | 0.834 | 0.575 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Banach, J.K.; Bojarska, J.E.; Ivanišová, E.; Harangozo, Ľ.; Kačániová, M.; Grzywińska-Rąpca, M.; Bieniek, A. Electrical Parameters as a Tool for Evaluating the Quality and Functional Properties of Superfruit Purees. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13180. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413180

Banach JK, Bojarska JE, Ivanišová E, Harangozo Ľ, Kačániová M, Grzywińska-Rąpca M, Bieniek A. Electrical Parameters as a Tool for Evaluating the Quality and Functional Properties of Superfruit Purees. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13180. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413180

Chicago/Turabian StyleBanach, Joanna Katarzyna, Justyna E. Bojarska, Eva Ivanišová, Ľuboš Harangozo, Miroslava Kačániová, Małgorzata Grzywińska-Rąpca, and Anna Bieniek. 2025. "Electrical Parameters as a Tool for Evaluating the Quality and Functional Properties of Superfruit Purees" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13180. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413180

APA StyleBanach, J. K., Bojarska, J. E., Ivanišová, E., Harangozo, Ľ., Kačániová, M., Grzywińska-Rąpca, M., & Bieniek, A. (2025). Electrical Parameters as a Tool for Evaluating the Quality and Functional Properties of Superfruit Purees. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13180. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413180