Impact of Radiomic and Artificial Intelligence on Colorectal Cancer: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data Source and Study Selection

3. Epidemiology and Risk Factors

4. Diagnosis and Clinical Management

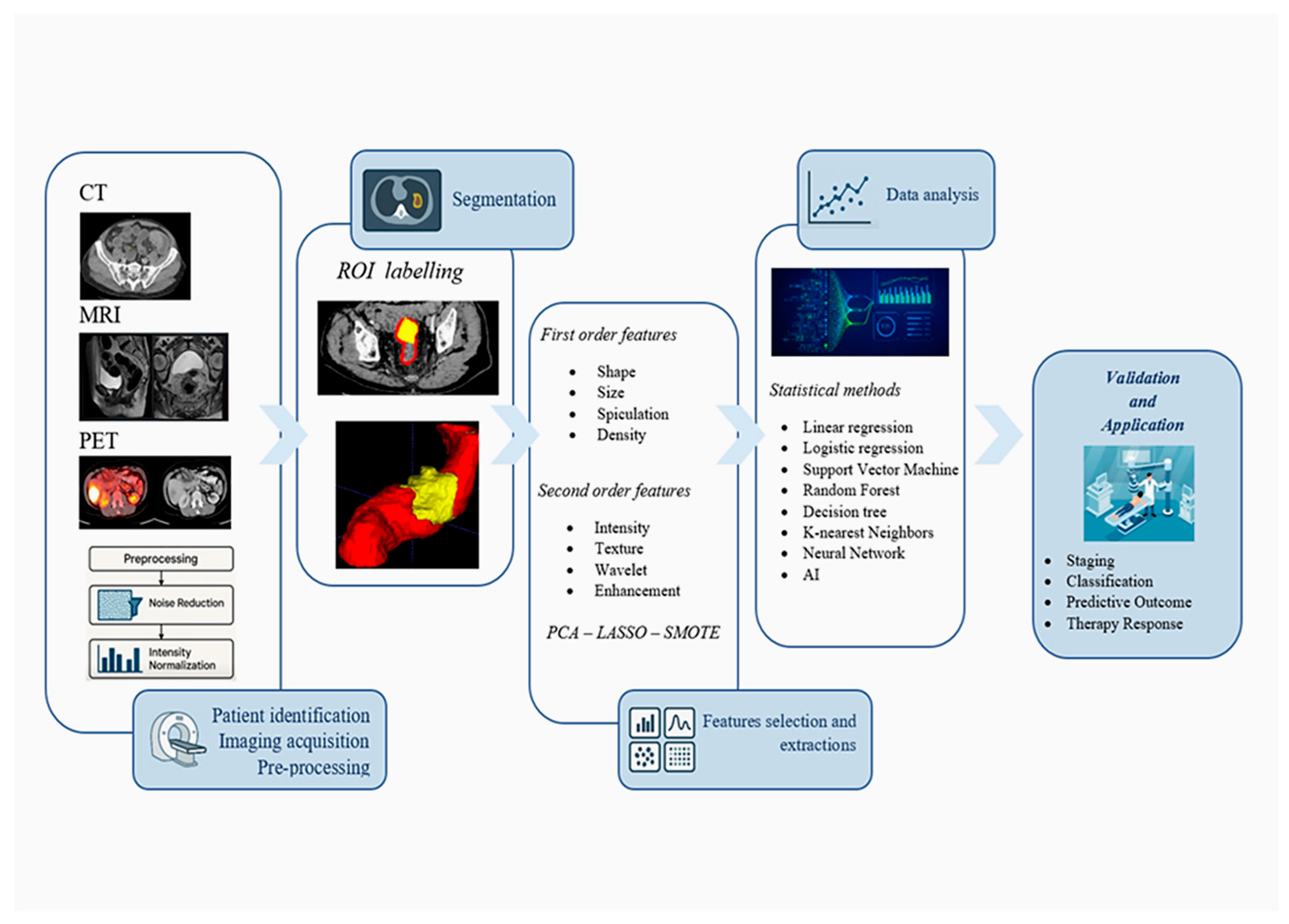

5. Radiomics and Artificial Intelligence

5.1. Image Acquisition and Preprocessing

5.2. Segmentation of Regions of Interest

5.3. Feature Extraction

5.4. Data Analysis and Dimensionality Reduction

6. Clinical Applications of Radiomics in Colorectal Cancer

6.1. Prediction of Therapy Response

6.2. Assessment of Vascular and Perineural Invasion

6.3. Prediction of Liver Metastases

6.4. Prediction of Genetic Mutations

6.5. Delta-Radiomics

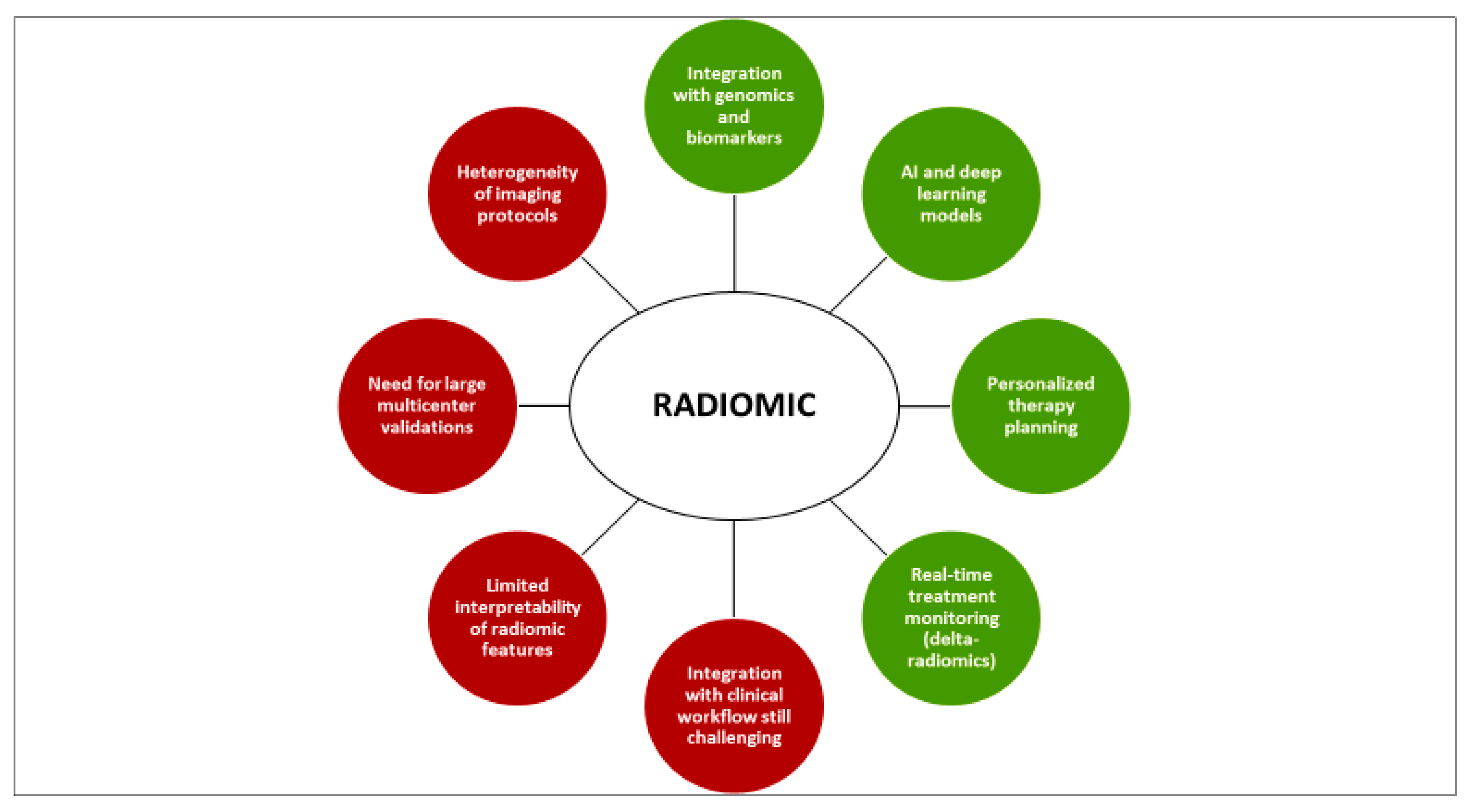

7. Limitations and Current Challenges

8. Future Perspectives

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, M.; Sierra, M.S.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut 2017, 66, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawla, P.; Sunkara, T.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: Incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Prz. Gastroenterol. 2019, 14, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanikachalam, K.; Khan, G. Colorectal cancer and nutrition. Nutrients 2019, 11, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D.; Keum, N.; Giovannucci, E.; Fadnes, L.T.; Boffetta, P.; Greenwood, D.C.; Tonstad, S.; Vatten, L.J.; Riboli, E.; Norat, T. Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 2016, 353, i2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, X.; Keum, N.; Wu, K.; Smith-Warner, S.A.; Ogino, S.; Chan, A.T.; Fuchs, C.S.; Giovannucci, E.L. Calcium intake and colorectal cancer risk: Results from the nurses’ health study and health professionals follow-up study. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 139, 2232–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Beaugerie, L.; Itzkowitz, S.H. Cancers complicating inflammatory bowel disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1441–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, A.; Kahi, C.J.; Burke, C.A.; Rabeneck, L.; Sauer, B.G.; Rex, D.K. ACG clinical guidelines: Colorectal cancer screening 2021. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 458–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.A.; Andrews, K.S.; Brooks, D.; Fedewa, S.A.; Manassaram-Baptiste, D.; Saslow, D.; Wender, R.C. Cancer screening in the United States, 2019: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 184–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciardiello, F.; Ciardiello, D.; Martini, G.; Napolitano, S.; Tabernero, J.; Cervantes, A. Clinical management of metastatic colorectal cancer in the era of precision medicine. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 372–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothey, A.; Fakih, M.; Tabernero, J. Management of BRAF-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer: A review of treatment options and evidence-based guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, C.R.; Goel, A. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 2073–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Paardt, M.P.; Zagers, M.B.; Beets-Tan, R.G.; Stoker, J.; Bipat, S. Patients who undergo preoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer restaged by using diagnostic MR imaging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology 2013, 269, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.T.; Heneghan, H.M.; Winter, D.C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes following pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2012, 99, 918–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambin, P.; Rios-Velazquez, E.; Leijenaar, R.; Carvalho, S.; van Stiphout, R.G.P.M.; Granton, P.; Zegers, C.M.L.; Gillies, R.; Boellard, R.; Dekker, A.; et al. Radiomics: Extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillies, R.J.; Kinahan, P.E.; Hricak, H. Radiomics: Images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiology 2016, 278, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, H.J.W.L.; Velazquez, E.R.; Leijenaar, R.T.H.; Parmar, C.; Grossmann, P.; Carvalho, S.; Bussink, J.; Monshouwer, R.; Haibe-Kains, B.; Rietveld, D.; et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, P.; Leijenaar, R.T.H.; Deist, T.M.; Peerlings, J.; de Jong, E.E.C.; van Timmeren, J.; Sanduleanu, S.; Larue, R.T.H.M.; Even, A.J.G.; Jochems, A.; et al. Radiomics: The bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, T.; Fujimoto, A.; Igarashi, Y. Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Public Health Strategies. Digestion 2025, 106, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofi, F.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Accruing evidence on benefits of adherence to the Mediterranean diet on health: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretan, B.; Straif, K.; Baan, R.; Grosse, Y.; El Ghissassi, F.; Bouvard, V.; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L.; Guha, N.; Freeman, C.; Galichet, L.; et al. A review of human carcinogens—Part E: Tobacco, areca nut, alcohol, coal smoke, and salted fish. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 1033–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasperson, K.W.; Tuohy, T.M.; Neklason, D.W.; Burt, R.W. Hereditary and familial colon cancer. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 2044–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, K.; Itabashi, T.; Sasaki, A.; Kimura, T.; Kato, K.; Wakabayashi, G. Laparoscopic-assisted proctocolectomy with prolapsing technique for familial adenomatous polyposis. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2014, 24, e228–e232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jess, T.; Rungoe, C.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Risk of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis: A meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell 1996, 87, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, H.T.; de la Chapelle, A. Hereditary colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 919–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, S.; Kastrinos, F.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Cook, E.F.; Dewanwala, A.; Burbidge, L.A.; Wenstrup, R.J.; Syngal, S. Prevalence and phenotypes of APC and MUTYH mutations in patients with multiple colorectal adenomas. JAMA 2012, 308, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imperiale, T.F.; Ransohoff, D.F.; Itzkowitz, S.H.; Levin, T.R.; Lavin, P.; Lidgard, G.P.; Ahlquist, D.A.; Berger, B.M. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal cancer screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, D.C.; Rustgi, A.K. A cell-free DNA blood-based test for colorectal cancer screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitzer, E.; Haque, I.S.; Roberts, C.E.S.; Speicher, M.R. Current and future perspectives of liquid biopsies in genomics-driven oncology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.B.; Greene, F.L.; Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Brookland, R.K.; Meyer, L.; Gress, D.M.; Byrd, D.R.; Winchester, D.P. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Lambregts, D.M.J.; Maas, M.; Beets, G.L. Magnetic resonance imaging for the clinical management of rectal cancer patients: Recommendations from the 2012 European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) consensus meeting. Eur. Radiol. 2013, 23, 2522–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamen, P.; Stroobants, S.; Van Cutsem, E.; Dupont, P.; Bormans, G.; De Vadder, N.; Penninckx, F.; Van Hoe, L.; Mortelmans, L. Additional value of whole-body positron emission tomography with fluorine-18-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose in recurrent colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999, 17, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, M.; Nelemans, P.J.; Valentini, V.; Das, P.; Rödel, C.; Kuo, L.J.; Calvo, F.A.; García-Aguilar, J.; Glynne-Jones, R.; Haustermans, K.; et al. Long-term outcome in patients with a pathological complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: A pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quasar Collaborative Group. Adjuvant chemotherapy versus observation in patients with colorectal cancer: A randomized study. Lancet 2007, 370, 2020–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, D.; Seymour, M.; Magill, L.; Handley, K.; Glasbey, J.; Glimelius, B.; Palmer, A.; Seligmann, J.; Laurberg, S.; Murakami, K.; et al. Preoperative Chemotherapy for Operable Colon Cancer: Mature Results of an International Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1541–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guler, I.; Askan, G.; Klostergaard, J.; Sahin, I.H. Precision medicine for metastatic colorectal cancer: An evolving era. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 13, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwanenburg, A.; Vallières, M.; Abdalah, M.A.; Aerts, H.J.W.L.; Andrearczyk, V.; Apte, A.; Ashrafinia, S.; Bakas, S.; Beukinga, R.J.; Boellaard, R.; et al. The Image Biomarker Standardization Initiative: Standardized quantitative radiomics for High-Throughput Image-based Phenotyping. Radiology 2020, 295, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Sun, J.H. Emerging applications of radiomics in rectal cancer: State of the art and future perspectives. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 3802–3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Gu, Y.; Basu, S.; Berglund, A.; Eschrich, S.A.; Schabath, M.B.; Forster, K.; Aerts, H.J.; Dekker, A.; Fenstermacher, D.; et al. Radiomics: The process and the challenges. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2012, 30, 1234–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Simone, C.B., 2nd; Krishnan, S.; Lin, S.H.; Yang, J.; Hahn, S.M. The Rise of Radiomics and Implications for Oncologic Management. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djx055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scapicchio, C.; Gabelloni, M.; Barucci, A.; Cioni, D.; Saba, L.; Neri, E. A deep look into radiomics. Radiol. Med. 2021, 126, 1296–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiot, J.; Vaidyanathan, A.; Deprez, L.; Zerka, F.; Danthine, D.; Frix, A.N.; Lambin, P.; Bottari, F.; Tsoutzidis, N.; Miraglio, B.; et al. A review in radiomics: Making personalized medicine a reality via routine imaging. Med. Res. Rev. 2022, 42, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larue, R.; Defraene, G.; De Ruysscher, D.; Lambin, P.; van Elmpt, W. Quantitative radiomics studies for tissue characterization: Review of technology and methodology. Br. J. Radiol. 2017, 90, 20160665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D.C.; Obuchowski, N.A.; Kessler, L.G.; Raunig, D.L.; Gatsonis, C.; Huang, E.P.; Kondratovich, M.; McShane, L.M.; Reeves, A.P.; Barboriak, D.P.; et al. Metrology Standards for Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers. Radiology 2015, 277, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerhoefer, M.E.; Materka, A.; Langs, G.; Häggström, I.; Szczypiński, P.; Gibbs, P.; Cook, G. Introduction to Radiomics. J. Nucl. Med. 2020, 61, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Griethuysen, J.J.M.; Fedorov, A.; Parmar, C.; Hosny, A.; Aucoin, N.; Narayan, V.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Fillion-Robin, J.C.; Pieper, S.; Aerts, H.J.W.L. Computational Radiomics System to Decode the Radiographic Phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, e104–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, A.; Beichel, R.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Finet, J.; Fillion-Robin, J.C.; Pujol, S.; Bauer, C.; Jennings, D.; Fennessy, F.; Sonka, M.; et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2012, 30, 1323–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayalibay, B.; Jensen, G.; van der Smagt, P. CNN-based segmentation of medical imaging data. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, C.; Rios Velazquez, E.; Leijenaar, R.; Jermoumi, M.; Carvalho, S.; Mak, R.H.; Mitra, S.; Shankar, B.U.; Kikinis, R.; Haibe-Kains, B. Robust Radiomics feature quantification using semiautomatic volumetric segmentation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Dong, D.; Song, J.; Xu, M.; Zang, Y.; Tian, J. Prediction of malignant and benign of lung tumor using a quantitative radiomic method. In Proceedings of the 2016 38th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Orlando, FL, USA, 16–20 August 2016; pp. 1272–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalati, M.K.; Nunes, A.; Ferreira, H.; Serranho, P.; Bernardes, R. Texture Analysis and Its Applications in Biomedical Imaging: A Survey. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 15, 222–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralick, R.M.; Shanmugam, K.; Dinstein, I. Textural features for image classification. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1973, SMC-3, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadasun, M.; King, R. Textural features corresponding to textural properties. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1989, 19, 1264–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depeursinge, A.; Foncubierta-Rodriguez, A.; Van De Ville, D.; Müller, H. Three-dimensional solid texture analysis in biomedical imaging: Review and opportunities. Med. Image Anal. 2014, 18, 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellman, R. Adaptive Control Processes: A Guided Tour; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Guyon, I.; Elisseeff, A. An introduction to variable and feature selection. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 1157–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the LASSO. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segato Dos Santos, L.F.; Neves, L.A.; Rozendo, G.B.; Ribeiro, M.G.; Zanchetta do Nascimento, M.; Azevedo Tosta, T.A. Multidimensional and fuzzy sample entropy (SampEnMF) for quantifying H&E histological images of colorectal cancer. Comput. Biol. Med. 2018, 103, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourou, K.; Exarchos, T.P.; Exarchos, K.P.; Karamouzis, M.V.; Fotiadis, D.I. Machine learning applications in cancer prognosis and prediction. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, B.; Durmaz, E.S.; Ateş, E.; Kılıçkesmez, Ö. Radiomics with artificial intelligence: A practical guide for beginners. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2019, 25, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapnik, V.N. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Hastie, T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 2005, 67, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Re, A.M.; Sun, Y.; Sundaresan, P.; Hau, E.; Toh, J.W.T.; Gee, H.; Or, M.; Haworth, A. MRI radiomics in the prediction of therapeutic response to neoadjuvant therapy for locoregionally advanced rectal cancer: A systematic review. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2021, 21, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, N.; Veeraraghavan, H.; Khan, M.; Blazic, I.; Zheng, J.; Capanu, M.; Sala, E.; Garcia-Aguilar, J.; Gollub, M.J.; Petkovska, I. MR Imaging of Rectal Cancer: Radiomics Analysis to Assess Treatment Response after Neoadjuvant Therapy. Radiology 2018, 287, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Wang, S.X.; Liu, P. Machine learning in predicting pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer using MRI: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Radiol. 2024, 97, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, E.; Rathee, S.; Blake, A.; Samuel, L.; Murray, G.; Sebag-Montefiore, D.; Gollins, S.; West, N.; Begum, R.; Richman, S.; et al. Identification and validation of a machine learning model of complete response to radiation in rectal cancer reveals immune infiltrate and TGFβ as key predictors. EBioMedicine 2024, 106, 105228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Prieto-de-la-Lastra, C.; Carbonell-Asins, J.A.; Bueno, A.; Gómez-Alderete, A.; Busto, M.; Alcolado-Jaramillo, A.B.; Jimenez-Pastor, A.; Monzonís, X.; Cuñat, A.; Montagut, C.; et al. A radiomics-based artificial intelligence model to assess the risk of relapse in localized colon cancer. ESMO Open 2025, 10, 105495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, J.S.; Kim, S.H.; Hur, B.Y.; Chang, W.; Park, J.; Park, H.E.; Kim, J.H.; Kang, H.J.; Yu, M.H.; Han, J.K. Prognostic value of MRI in assessing extramural venous invasion in rectal cancer: Multi-readers’ diagnostic performance. Eur. Radiol. 2019, 29, 4379–4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, D.; Pang, P.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, X.; Liao, J. Pretreatment MR-based radiomics nomogram as potential imaging biomarker for individualized assessment of perineural invasion status in rectal cancer. Abdom. Radiol. 2021, 46, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Z.; Fang, S.; Ding, Z.; Mao, D.; Cai, R.; Chen, Y.; Pang, P.; Gong, X. MRI-based Radiomics nomogram to detect primary rectal cancer with synchronous liver metastases. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Ma, X.; Shen, F.; Xia, Y.; Jia, Y.; Lu, J. MRI-based radiomics nomogram to predict synchronous liver metastasis in primary rectal cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 5155–5163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, R.C.J.; Lambregts, D.M.J.; Schnerr, R.S.; Maas, M.; Rao, S.X.; Kessels, A.G.H.; Thywissen, T.; Beets, G.L.; Trebeschi, S.; Houwers, J.B.; et al. Whole liver CT texture analysis to predict the development of colorectal liver metastases-A multicentre study. Eur. J. Radiol. 2017, 92, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Xia, W.; Xie, P.; Zhang, R.; Li, W.; Wang, M.; Xiong, F.; Liu, Y.; Fan, X.; Xie, Y.; et al. Preoperative radiomic signature based on multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for noninvasive evaluation of biological characteristics in rectal cancer. Eur. Radiol. 2019, 29, 3200–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Yao, Q.; Qu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, J.; Feng, W.; Zhang, S.; Han, X.; Wang, S.; et al. The value of intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion-weighted imaging in predicting the pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 1391–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.E.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, J.; Hur, B.Y.; Kim, B.; Kim, D.Y.; Baek, J.Y.; Chang, H.J.; Park, S.C.; Oh, J.H.; et al. Magnetic Resonance-Based Texture Analysis Differentiating KRAS Mutation Status in Rectal Cancer. Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 52, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dercle, L.; Lu, L.; Schwartz, L.H.; Qian, M.; Tejpar, S.; Eggleton, P.; Zhao, B.; Piessevaux, H. Radiomics Response Signature for Identification of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Sensitive to Therapies Targeting EGFR Pathway. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020, 112, 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, V.; Pusceddu, L.; Defeudis, A.; Nicoletti, G.; Cappello, G.; Mazzetti, S.; Sartore-Bianchi, A.; Siena, S.; Vanzulli, A.; Rizzetto, F.; et al. Delta-Radiomics Predicts Response to First-Line Oxaliplatin-Based Chemotherapy in Colorectal Cancer Patients with Liver Metastases. Cancers 2022, 14, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardone, V.; Reginelli, A.; Grassi, R.; Boldrini, L.; Vacca, G.; D’Ippolito, E.; Annunziata, S.; Farchione, A.; Belfiore, M.P.; Desideri, I.; et al. Delta radiomics: A systematic review. Radiol. Med. 2021, 126, 1571–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.Y.; Shi, Y.J.; Wang, L.; Zhu, H.T.; Tang, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, X.T.; Tian, J.; Sun, Y.S. Radiomics Analysis for Evaluation of Pathological Complete Response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 7253–7262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Yang, X.; Shi, Z.; Yang, Z.; Du, X.; Zhao, Z.; Cheng, X. Radiomics analysis of multiparametric MRI for prediction of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Eur. Radiol. 2019, 29, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Li, M.; Jin, Y.M.; Xu, J.X.; Huang, C.C.; Song, B. Radiomics for differentiating tumor deposits from lymph node metastasis in rectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 3960–3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Z.; Mao, D.; Song, Q.; Xu, Y.; Pang, P.; Zhang, Y. Multiparameter MRI-based radiomics for preoperative prediction of extramural venous invasion in rectal cancer. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 1002–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wang, Z.; Lai, S.; Meng, L.; Lu, Y.; Lu, X.; Lin, L.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Mo, S.; et al. Comparative study of radiomics, tumor morphology, and clinicopathological factors in predicting overall survival of patients with rectal cancer before surgery. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 18, 101352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiazi, R.; Abbas, E.; Famiyeh, P.; Rezaie, A.; Kwan, J.Y.Y.; Patel, T.; Bratman, S.V.; Tadic, T.; Liu, F.F.; Haibe-Kains, B. The impact of the variation of imaging parameters on the robustness of Computed Tomography radiomic features: A review. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 133, 104400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whybra, P.; Spezi, E. Sensitivity of standardised radiomics algorithms to mask generation across different software platforms. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, B.; Shi, X.; Li, B.; Xie, J.; Wang, C. Application research of radiomics in colorectal cancer: A bibliometric study. Medicine 2024, 103, e37827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aguirre-Meneses, H.; Stoehr-Muñoz, P.; Molina-Gonzalez, M.; Nuñez-Gaona, M.A.; Roldan-Valadez, E. Radiomics and the Image Biomarker Standardisation Initiative (IBSI): A Narrative Review Using a Six-Question Map and Implementation Framework for Reproducible Imaging Biomarkers. Cureus 2025, 17, e95335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, A.; Biemann, C.; Pattichis, C.S.; Kell, D.B. Explainable AI: The new 42? Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2020, 140, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samek, W.; Wiegand, T.; Müller, K.R. Explainable artificial intelligence: Understanding, visualizing, and interpreting deep learning models. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.08296. [Google Scholar]

- Volpe, S.; Mastroleo, F.; Krengli, M.; Jereczek-Fossa, B.A. Quo vadis Radiomics? Bibliometric analysis of 10-year Radiomics journey. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 33, 6736–6745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aida, S.; Okugawa, J.; Fujisaka, S.; Kasai, T.; Kameda, H.; Sugiyama, T. Deep Learning of Cancer Stem Cell Morphology Using Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aerts, H.J.W.L. The potential of radiomic biomarkers to guide precision medicine in oncology. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1636–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardin, I.; Grégoire, V.; Gibon, D.; Kirisli, H.; Pasquier, D.; Thariat, J.; Vera, P. Radiomics: Principles and radiotherapy applications. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2019, 138, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abenavoli, L.; Guzzi, P.H. Artificial intelligence in gastroenterology—Promises and limits. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2024, 33, 444–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abenavoli, L.; Scarlata, G.G.M.; Gambardella, M.L.; Battaglia, C.; Borelli, M.; Manti, F.; Laganà, D. Combined model for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: A pilot study comparing the liver to spleen volume ratio and liver vein to cava attenuation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author/s and Year (Ref.) | Clinical Application | Imaging Modality | AI/Radiomics Methodology | Main Outcome (Metrics) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu Z, et al. (2017) [83] | Prediction of pCR to nCRT | MRI (T2WI + DWI) | Radiomics model (LASSO + SVM + clinical) | AUC = 0.98 (in the external validation cohort) |

| Cui Y, et al. (2019) [84] | Prediction of pCR to nCRT | MP-MRI (T2w, cT1w, ADC) | Radiomics nomogram (LASSO + clinical) | AUC = 0.966 (in the validation cohort) |

| Horvat N, et al. (2018) [68] | Prediction of pCR to nCRT | MRI (T2-weighted) | Radiomics score (LASSO) | AUC = 0.77 (in the external validation cohort) |

| Zhang YC, et al. (2022) [85] | Differentiating tumor deposits (TDs) from lymph node metastasis (LNM) | CT | Radiomics signature from the largest peritumoral nodule | AUC = 0.918 (in the validation cohort) |

| Shu Z, et al. (2022) [86] | Prediction of extramural venous invasion (EMVI) | MP-MRI | Joint model (Bayes-based radiomics + clinical factors) | AUC = 0.835 (in the test set) |

| Chen J, et al. (2021) [73] | Prediction of Perineural Invasion (PNI) | MRI (T2-weighted) | Radiomics nomogram (mRMR & LASSO) | AUC = 0.85 (in the test cohort) |

| Bae JS, et al. (2019) [72] | Assessment of Extramural Venous Invasion (EMVI) | MRI (T2-weighted) | Radiomics assessment (ROC curve analysis) | AUC = 0.829 (experienced radiologist) |

| Oh JE, et al. (2020) [79] | Differentiation of KRAS mutation status | MRI (T2-weighted) | Texture analysis (Decision tree model) | AUC = 0.884 (on the whole dataset) |

| Meng X, et al. (2019) [77] | Prediction of various biological characteristics | MP-MRI | Radiomics signature (various selectors & classifiers) | AUCs (validation): Differentiation = 0.720; Ki-67 = 0.699 KRAS = 0.651 |

| Liu M, et al. (2020) [75] | Prediction of synchronous liver metastasis (SLM) | MRI (T2-weighted) | Radiomics nomogram (LASSO + clinical factors) | AUC = 0.944 (in the validation cohort) |

| Giannini V, et al. (2022) [81] | Prediction of therapy response of liver metastases to FOLFOX | CT | Delta-radiomics signature (Decision tree) | AUC = 0.93(in the validation cohort) |

| Shu Z, et al. (2019) [74] | Prediction of synchronous liver metastasis (SLM) | MRI (T2-weighted) | Radiomics nomogram (feature selection with LASSO) | AUC = 0.912 (in the validation cohort) |

| Dercle L, et al. (2020) [80] | Prediction of therapy response to anti-EGFR treatment | CT | Delta-radiomics signature (Random Forest) | AUC = 0.80 (in the validation cohort) |

| Chuanji Z, et al. (2022) [87] | Prediction of 3-year overall survival (OS) | MRI (T2-weighted) | Comprehensive nomogram (radiomics, morphological & clinical) | C-index = 0.944 (in the validation cohort) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Battaglia, C.; Gambardella, M.L.; Morano, D.; Cannavò, S.; Abenavoli, L.; Laganà, D.; Arcuri, P.P. Impact of Radiomic and Artificial Intelligence on Colorectal Cancer: A Narrative Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13174. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413174

Battaglia C, Gambardella ML, Morano D, Cannavò S, Abenavoli L, Laganà D, Arcuri PP. Impact of Radiomic and Artificial Intelligence on Colorectal Cancer: A Narrative Review. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13174. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413174

Chicago/Turabian StyleBattaglia, Caterina, Maria Luisa Gambardella, Domenico Morano, Salvatore Cannavò, Ludovico Abenavoli, Domenico Laganà, and Pier Paolo Arcuri. 2025. "Impact of Radiomic and Artificial Intelligence on Colorectal Cancer: A Narrative Review" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13174. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413174

APA StyleBattaglia, C., Gambardella, M. L., Morano, D., Cannavò, S., Abenavoli, L., Laganà, D., & Arcuri, P. P. (2025). Impact of Radiomic and Artificial Intelligence on Colorectal Cancer: A Narrative Review. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13174. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413174