Application of Environmental Lactic Acid Bacteria in the Production of Mechanically Separated Poultry Meat Against Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains and the Solution for Application to Bones

2.2. Raw Material and Experiment Design

- C1: control—only bones;

- C2: control—bones treated with a 2.0% saline solution and 0.1% glucose;

- L1—bones treated with a 2.0% saline solution and L. plantarum SCH1 (≈107 CFU/g) and 0.1% glucose;

- L2—bones treated with a 2.0% saline solution and L. fermentum S8 (≈107 CFU/g) and 0.1% glucose;

- L3—bones treated with 2.0% saline solution and P. pentosaceus KL14 (≈107 CFU/g) and 0.1% glucose.

2.3. Determination of pH Value and ORP

2.4. Lipid Oxidation Indicator

2.5. Fatty Acid Profile Determination

2.6. Colour Determination

2.7. Microbiological Analyses

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

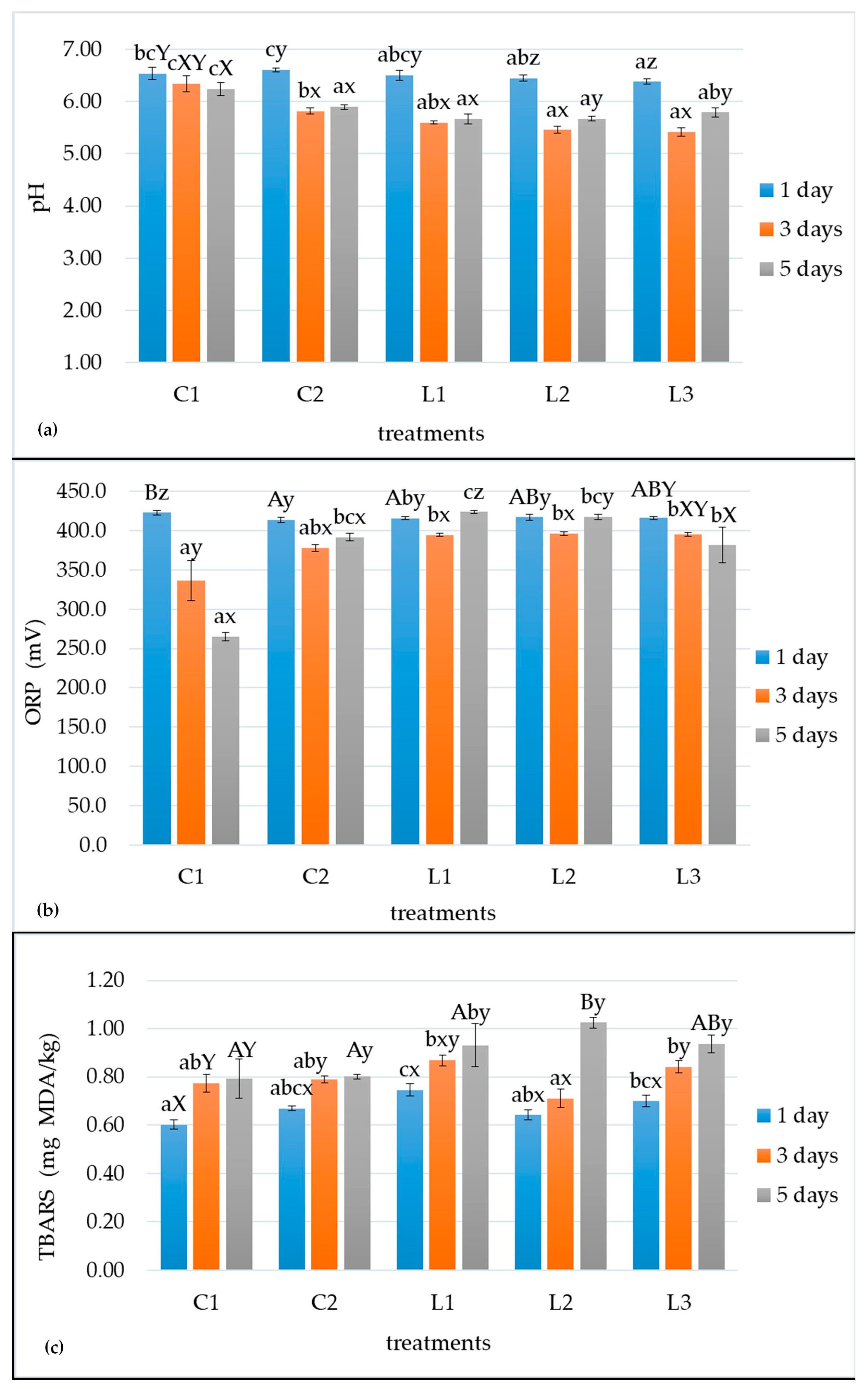

3.1. Changes in pH and ORP

3.2. Lipid Oxidation Indicator (TBARS)

3.3. Fatty Acid Profile

3.4. Colour

3.5. Microbiological Quality

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSPM | Mechanically separated poultry meat |

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

| CoPS | Coagulase-positive staphylococci |

| CoNS | Coagulase-negative staphylococci |

| ORP | Oxidation Reduction Potential |

| CFU | Colony forming unit |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances |

| SFA | Saturated fatty acid |

| MUFA | Monounsaturated fatty acid |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- UNEP Food Waste Index Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Łaszkiewicz, B.; Szymański, P.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Quality problems in mechanically separated meat. Med. Weter. 2019, 75, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Parliament. Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 Laying Down Specific Hygiene Rules for Food of Animal Origin; The Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pomykała, R.; Michalski, M. Microbiological quality of mechanically separated poultry meat. Acta Sci. Pol. Med. Vet. 2008, 7, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, P.D.; de Almeida, T.T.; Basso, A.P.; de Moura, T.M.; Frazzon, J.; Tondo, E.C.; Frazzon, A.P.G. Coagulase-positive staphylococci isolated from chicken meat: Pathogenic potential and vancomycin resistance. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2013, 10, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, H.; Mørk, T.; Caugant, D.; Kearns, A.; Rørvik, L. Genetic variation among Staphylococcus aureus strains from Norwegian bulk milk. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 8352–8361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josefowitz, P. Histological, Microbiological and Chemical Characteristics of the Quality of Mechanically Separated Turkey Meat. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Food Hygiene, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Free University of Berlin, Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sindelar, J.J.; Milkowski, A.L. Sodium Nitrite in Processed Meat and Poultry Meats: A Review of Curing and Examining the Risk/Benefit of Its Use. Am. Meat Sci. Assoc. White Pap. Ser. 2011, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- The European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/2108; EN L Series; Official Journal of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/2108/oj (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS); Mortensen, A.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Di Domenico, A.; Dusemund, B.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; Gott, D.; Gundert-Remy, U.; et al. Re-evaluation of potassium nitrite (E 249) and sodium nitrite (E 250) as food additives. EFSA J. 2017, 15, e04786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzepkowska, A.; Zielińska, D.; Ołdak, A.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Safety assessment and antimicrobial properties of the lactic acid bacteria strains isolated from polish raw fermented meat products. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 2736–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugas, M.; Monfort, J.M. Bacterial starter cultures for meat fermentation. Food Chem. 1997, 59, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raccach, M.; Baker, R.C. Lactic Acid Bacteria as an Antispoilage and Safety Factor in Cooked, Mechanically Deboned Poultry Meat. J. Food Prot. 1978, 41, 703–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecer, C.; Sözen, B.H.U. Microbiological properties of mechanically deboned poultry meat that applied lactic acid, acetic acid and sodium lactate. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 6, 3847–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łaszkiewicz, B.; Szymański, P.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Wpływ wybranych szczepów bakterii kwasu mlekowego na przydatność technologiczną i jakość mikrobiologiczną mięsa drobiowego oddzielonego mechanicznie [Impact of selected lactic acid bacteria strains on technological usability and microbiological quality of mechanically separated poultry meat]. Żywność Nauka Technol. Jakość 2019, 26, 122–134. [Google Scholar]

- Łaszkiewicz, B.; Szymański, P.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. The effect of selected lactic acid bacterial strains on the technological and microbiological quality of mechanically separated poultry meat cured with a reduced amount of sodium nitrite. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzepkowska, A.; Zielińska, D.; Ołdak, A.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Organic whey as a source of Lactobacillus strains with selected technological and antimicrobial properties. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 1983–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łaszkiewicz, B.; Szymański, P.; Zielińska, D.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Application of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum SCH1 for the Bioconservation of Cooked Sausage Made from Mechanically Separated Poultry Meat. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikul, J.; Leszczynski, D.E.; Kummerow, F.A. Evaluation of three modified TBA methods for measuring lipid oxidation in chicken meat. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1989, 37, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 12966-1:2014; Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils—Gas Chromatography of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters—Part 1: Guidelines on Modern Gas Chromatography of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/52294.html (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Okoń, A.; Szymański, P.; Zielińska, D.; Szydłowska, A.; Siekierko, U.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D.; Dolatowski, Z.J. The Influence of Acid Whey on the Lipid Composition and Oxidative Stability of Organic Uncured Fermented Bacon after Production and during Chilling Storage. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, M.C.; King, A.; Barbut, S.; Clause, J.; Cornforth, D.; Hanson, D.; Lindahl, G.; Mancini, R.; Milkowski, A.; Mohan, A. AMSA Meat Color Measurement Guidelines; American Meat Science Association: Kearney, MO, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 4833-1:2013; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Microorganisms. Part 1: Colony Count at 30 °C by the Pour Plate Technique. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/53728.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- ISO 15214:1998; Microbiology of Food and Animal Feeding Stuffs—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Mesophilic Lactic Acid Bacteria—Colony-Count Technique at 30 Degrees C. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/26853.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- ISO 16649-1:2018; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Beta-Glucuronidase-Positive Escherichia Coli. Part 1: Colony-Count Technique at 44 Degrees C Using Membranes and 5-Bromo-4-Chloro-3-Indolyl Beta-D-Glucuronide. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/64951.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- ISO 21528-2:2017; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Enterobacteriaceae. Part 2: Colony-Count Technique. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/63504.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- ISO 6888-1:2021; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci (Staphylococcus aureus and Other Species). Part 1: Method Using Baird-Parker Agar Medium. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/76672.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Ha, M.Y.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, Y.W.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, S.J. Kinetics analysis of growth and lactic acid production in pH-controlled batch cultures of Lactobacillus casei KH-1 using yeast extract/corn steep liquor/glucose medium. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2003, 96, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balciunas, E.M.; Martinez, F.A.C.; Todorov, S.D.; de Melo Franco, B.D.G.; Converti, A.; de Souza Oliveira, R.P. Novel biotechnological applications of bacteriocins: A review. Food Control. 2013, 32, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, J.; Wang, D.; Gao, F.; Zhang, K.; Tian, J.; Jin, Y. Research Update on the Impact of Lactic Acid Bacteria on the Substance Metabolism, Flavor, and Quality Characteristics of Fermented Meat Products. Foods 2022, 11, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondjoyan, A.; Sicard, J.; Cucci, P.; Audonnet, F.; Elhayel, H.; Lebert, A.; Scislowski, V. Predicting the Oxidative Degradation of Raw Beef Meat during Cold Storage Using Numerical Simulations and Sensors-Prospects for Meat and Fish Foods. Foods 2022, 11, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, J.W.; Leenhouts, K.J.; Haandrikman, A.J.; Venema, G.; Kok, J. Stress response in Lactococcus lactis: Cloning, expressionanalysis, and mutation of the lactococcal superoxide dismutase gene. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 5254–5260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maresca, D.; Zotta, T.; Mauriello, G. Adaptation to Aerobic Environment of Lactobacillus johnsonii/gasseri Strains. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, T.; Kono, Y.; Tanaka, K. Molecular cloning of manganese catalase from Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 29521–29524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikowska-Karpińska, E.; Moniuszko-Jakoniuk, J. The antioxidative barrier in the organism. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2004, 13, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Reitznerová, A.; Šuleková, M.; Nagy, J.; Marcinčák, S.; Semjon, B.; Čertík, M.; Klempová, T. Lipid Peroxidation Process in Meat and Meat Products: A Comparison Study of Malondialdehyde Determination between Modified 2-Thiobarbituric Acid Spectrophotometric Method and Reverse-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. Molecules 2017, 22, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R.; Pateiro, M.; Gagaoua, M.; Barba, F.J.; Zhang, W.; Lorenzo, J.M. A Comprehensive Review on Lipid Oxidation in Meat and Meat Products. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łepecka, A.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Antioxidant Properties of Food-Derived Lactic Acid Bacteria: A Review. Microb. Biotechnol. 2025, 18, e70229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, A.B.; Silva, M.V.D.; Lannes, S.C.D.S. Lipid oxidation in meat: Mechanisms and protective factors—A review. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 38 (Suppl. S1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N.; Singh, P.K.; Jairath, G.; Ahmad, M.F.; Raposo, A.; Khanam, A.; Alarifi, S.N.; Han, H.; Thakur, N. Physico-chemical changes in developed probiotic chicken meat spread fermented with Lactobacillus acidophilus and malted millet flour. Appl. Food Res. 2024, 4, 100484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegiełka, A.; Hać-Szymańczuk, E.; Piwowarek, K.; Dasiewicz, K.; Słowiński, M.; Wrońska, K. The use of bioactive properties of sage preparations to improve the storage stability of low-pressure mechanically separated meat from chickens. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 5045–5053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akramzadeh, N.; Ramezani, Z.N.; Ferdousi, R.; Akbari-adergani, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Karimian-khosroshahi, N.; Khalili Famenin, B.; Pilevar, Z.; Hosseini, H. Effect of chicken raw materials on physicochemical and microbiological properties of mechanically deboned chicken meat. Vet. Res. Forum 2020, 11, 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, L. Oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids and its impact on food quality and human health. Adv. Food Technol. Nutr. Sci. Open J. 2015, 1, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faustman, C.; Sun, Q.; Mancini, R.; Suman, S.P. Myoglobin and lipid oxidation interactions: Mechanistic bases and control. Meat Sci. 2010, 86, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hopkins, D.L.; Liang, R.; Dong, P.; Zhu, L. Effects of microbiota dynamics on the color stability of chilled beef steaks stored in high oxygen and carbon monoxide packaging. Food Res. Int. 2020, 134, 109215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlier, C.; Cretenet, M.; Even, S.; Le Loir, Y. Interactions between Staphylococcus aureus and lactic acid bacteria: An old story with new perspectives. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 131, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbowiak, M.; Gałek, M.; Szydłowska, A.; Zielińska, D. The influence of the degree of thermal inactivation of probiotic lactic acid bacteria and their postbiotics on aggregation and adhesion inhibition of selected pathogens. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Storage Time (Days) | T | S | T × S | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | p | p | p | ||

| ∑SFA (%) | C1 | 28.07 ± 0.31 abX | 28.37 ± 0.78 ABX | *** | *** | *** |

| C2 | 27.80 ± 0.21 abX | 28.00 ± 0.21 AX | ||||

| L1 | 27.57 ± 0.27 ax | 28.47 ± 0.25 ABy | ||||

| L2 | 28.33 ± 0.17 bx | 29.17 ± 0.23 By | ||||

| L3 | 27.83 ± 0.21 abx | 28.50 ± 0.00 ABy | ||||

| ∑MUFA (%) | C1 | 42.97 ± 0.44 abX | 43.37 ± 0.48 aX | *** | *** | *** |

| C2 | 43.17 ± 0.35 bcX | 43.67 ± 0.48 abX | ||||

| L1 | 42.53 ± 0.44 ax | 43.60 ± 0.37 aby | ||||

| L2 | 44.20 ± 0.32 dx | 45.33 ± 0.12 cy | ||||

| L3 | 43.60 ± 0.35 cdx | 44.57 ± 0.38 bcy | ||||

| ∑PUFA (%) | C1 | 28.77 ± 0.48 bX | 28.07 ± 1.15 bX | *** | *** | *** |

| C2 | 28.93 ± 0.27 bY | 28.03 ± 0.35 bX | ||||

| L1 | 29.70 ± 0.37 cy | 27.67 ± 0.29 bx | ||||

| L2 | 27.33 ± 0.17 ay | 25.37 ± 0.23 ax | ||||

| L3 | 28.40 ± 0.27 by | 26.83 ± 0.17 abx | ||||

| ∑n3 (%) | C1 | 2.77 ± 0.15 ABX | 2.63 ± 0.15 abX | *** | *** | *** |

| C2 | 2.97 ± 0.06 By | 2.73 ± 0.06 bx | ||||

| L1 | 2.93 ± 0.06 ABy | 2.60 ± 0.00 abx | ||||

| L2 | 2.73 ± 0.06 Ay | 2.37 ± 0.06 ax | ||||

| L3 | 2.87 ± 0.06 ABy | 2.53 ± 0.06 abx | ||||

| ∑n6 (%) | C1 | 0.67 ± 0.06 AX | 0.73 ± 0.16 BX | * | * | * |

| C2 | 0.60 ± 0.00 AX | 0.63 ± 0.06 ABX | ||||

| L1 | 0.73 ± 0.06 AX | 0.63 ± 0.06 ABX | ||||

| L2 | 0.63 ± 0.06 AY | 0.50 ± 0.00 AX | ||||

| L3 | 0.67 ± 0.06 AX | 0.60 ± 0.00 ABX | ||||

| Parameter | Storage Time (Days) | T | S | T × S | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 5 | p | p | p | ||

| L* | C1 | 50.36 ± 1.72 ay | 51.41 ± 1.20 az | 49.28 ± 0.98 ax | *** | *** | *** |

| C2 | 50.33 ± 1.31 ax | 53.05 ± 1.07 by | 53.17 ± 1.10 by | ||||

| L1 | 52.25 ± 1.11 bx | 54.12 ± 0.76 cy | 55.30 ± 0.71 cz | ||||

| L2 | 51.76 ± 0.97 bx | 55.05 ± 0.98 dy | 56.36 ± 1.01 dz | ||||

| L3 | 51.76 ± 1.02 bx | 53.66 ± 0.90 bcy | 55.39 ± 0.94 cz | ||||

| a* | C1 | 17.25 ± 1.63 Ax | 18.83 ± 1.36 cy | 16.19 ± 1.73 cx | *** | *** | *** |

| C2 | 17.42 ± 1.71 Ay | 17.40 ± 1.17 by | 15.17 ± 1.19 bx | ||||

| L1 | 16.58 ± 1.38 Ay | 16.51 ± 1.21 aby | 13.12 ± 0.94 ax | ||||

| L2 | 16.74 ± 1.71 Az | 15.50 ± 1.15 ay | 13.08 ± 0.74 ax | ||||

| L3 | 16.74 ± 1.30 Ay | 16.38 ± 1.32 aby | 13.62 ± 0.76 ax | ||||

| b* | C1 | 14.59 ± 1.41 ax | 16.06 ± 1.32 by | 14.36 ± 1.12 Ax | *** | *** | *** |

| C2 | 15.29 ± 1.07 abXY | 15.70 ± 1.72 aY | 15.05 ± 1.72 BCX | ||||

| L1 | 16.22 ± 0.81 cy | 15.79 ± 0.90 aby | 14.88 ± 0.87 ABCx | ||||

| L2 | 15.61 ± 1.16 bcX | 15.11 ± 1.14 aX | 15.10 ± 0.73 CX | ||||

| L3 | 15.12 ± 0.97 abxy | 15.38 ± 1.09 aby | 14.43 ± 0.84 ABx | ||||

| h° | C1 | 40.24 ± 2.06 aX | 40.45 ± 1.55 aX | 41.66 ± 2.13 aY | *** | *** | *** |

| C2 | 41.35 ± 1.99 abx | 42.08 ± 1.22 bx | 44.81 ± 1.82 by | ||||

| L1 | 44.44 ± 1.88 dx | 43.74 ± 1.37 cx | 48.61 ± 1.98 dy | ||||

| L2 | 43.06 ± 2.27 cdx | 44.27 ± 1.57 cx | 49.11 ± 1.57 dy | ||||

| L3 | 42.11 ± 1.13 bcx | 43.22 ± 1.34 bcx | 46.63 ± 2.01 cy | ||||

| C* | C1 | 22.60 ± 2.01 Ax | 24.76 ± 1.78 cy | 21.65 ± 1.91 cx | *** | *** | *** |

| C2 | 23.19 ± 1.85 Ay | 23.44 ± 1.37 by | 21.39 ± 1.30 bcx | ||||

| L1 | 23.21 ± 1.41 Ay | 22.85 ± 1.41 aby | 19.85 ± 0.87 ax | ||||

| L2 | 22.91 ± 1.86 Az | 21.66 ± 1.57 ay | 19.99 ± 0.88 ax | ||||

| L3 | 22.56 ± 1.56 Ay | 22.47 ± 1.63 aby | 19.85 ± 0.90 abx | ||||

| Parameter | Storage Time (Days) | T | S | T × S | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 5 | p | p | p | ||

| TVC, (log CFU/g) | C1 | 7.58 ± 0.24 Ax | 9.08 ± 0.44 By | 8.76 ± 0.15 Ay | ** | ** | * |

| C2 | 7.35 ± 0.20 Ax | 8.42 ± 0.26 ABy | 8.60 ± 0.17 Ay | ||||

| L1 | 7.55 ± 0.14 Ax | 8.29 ± 0.12 ABy | 8.26 ± 0.13 Ay | ||||

| L2 | 7.54 ± 0.25 AX | 8.45 ± 0.13 ABY | 8.34 ± 0.35 AY | ||||

| L3 | 7.82 ± 0.48 AX | 8.19 ± 0.37 AX | 8.46 ± 0.36 AX | ||||

| LAB, (log CFU/g) | C1 | 6.86 ± 0.08 ABx | 7.58 ± 0.07 Ay | 8.24 ± 0.15 abz | ** | *** | *** |

| C2 | 6.34 ± 0.45 Ax | 7.82 ± 0.20 Ay | 7.72 ± 0.06 ay | ||||

| L1 | 6.36 ± 0.38 Ax | 7.62 ± 0.28 Axy | 8.49 ± 0.43 aby | ||||

| L2 | 6.87 ± 0.12 ABx | 7.90 ± 0.09 Ay | 8.84 ± 0.18 bz | ||||

| L3 | 7.30 ± 0.10 Bx | 7.97 ± 0.23 Ay | 7.89 ± 0.09 ay | ||||

| Ec, (log CFU/g) | C1 | 5.08 ± 0.13 Ax | 6.41 ± 0.17 Ay | 6.47 ± 0.40 aby | * | *** | ** |

| C2 | 5.11 ± 0.12 Ax | 6.32 ± 0.28 Ay | 6.43 ± 0.38 aby | ||||

| L1 | 5.48 ± 0.18 AX | 6.36 ± 0.39 AY | 6.45 ± 0.35 abY | ||||

| L2 | 4.95 ± 0.35 Ax | 6.59 ± 0.16 Ay | 5.59 ± 0.16 ax | ||||

| L3 | 5.44 ± 0.28 Ax | 6.52 ± 0.07 Ay | 6.91 ± 0.27 by | ||||

| EB, (log CFU/g) | C1 | 6.41 ± 0.10 ax | 7.44 ± 0.28 Ay | 8.26 ± 0.24 bcz | *** | *** | *** |

| C2 | 6.82 ± 0.07 aX | 7.77 ± 0.67 AXY | 7.99 ± 0.13 abcY | ||||

| L1 | 7.40 ± 0.26 bX | 7.84 ± 0.31 AX | 7.54 ± 0.32 abX | ||||

| L2 | 6.91 ± 0.11 abX | 7.15 ± 0.20 AX | 7.25 ± 0.30 aX | ||||

| L3 | 7.41 ± 0.10 bx | 7.81 ± 0.22 Ax | 8.61 ± 0.14 cy | ||||

| CoPS, (log CFU/g) | C1 | 4.59 ± 0.47 Ax | 6.25 ± 0.19 Ay | 6.75 ± 0.26 cy | *** | *** | ** |

| C2 | 4.86 ± 0.88 AX | 5.73 ± 0.75 AXY | 6.63 ± 0.31 cY | ||||

| L1 | 4.79 ± 0.20 Ay | 5.33 ± 0.26 Ay | 2.30 ± 0.18 ax | ||||

| L2 | 4.82 ± 0.07 Ax | 5.43 ± 0.17 Ay | 5.10 ± 0.17 bxy | ||||

| L3 | 4.59 ± 0.11 AX | 5.64 ± 0.41 AY | 5.23 ± 0.29 bXY | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Łaszkiewicz, B.; Łepecka, A.; Okoń, A.; Siekierko, U.; Szymański, P. Application of Environmental Lactic Acid Bacteria in the Production of Mechanically Separated Poultry Meat Against Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13032. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413032

Łaszkiewicz B, Łepecka A, Okoń A, Siekierko U, Szymański P. Application of Environmental Lactic Acid Bacteria in the Production of Mechanically Separated Poultry Meat Against Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13032. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413032

Chicago/Turabian StyleŁaszkiewicz, Beata, Anna Łepecka, Anna Okoń, Urszula Siekierko, and Piotr Szymański. 2025. "Application of Environmental Lactic Acid Bacteria in the Production of Mechanically Separated Poultry Meat Against Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13032. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413032

APA StyleŁaszkiewicz, B., Łepecka, A., Okoń, A., Siekierko, U., & Szymański, P. (2025). Application of Environmental Lactic Acid Bacteria in the Production of Mechanically Separated Poultry Meat Against Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13032. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413032