Adaptive Feature Representation Learning for Privacy-Fairness Joint Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- We propose an adaptive low-rank embedding learning (ALEL) module that reformulates matrix factorization as a learnable low-dimensional embedding process. By jointly optimizing task loss, fairness regularization, and privacy-related reconstruction loss, ALEL produces text representations that are simultaneously discriminative, less dependent on sensitive attributes, and less vulnerable to privacy leakage.

- 2.

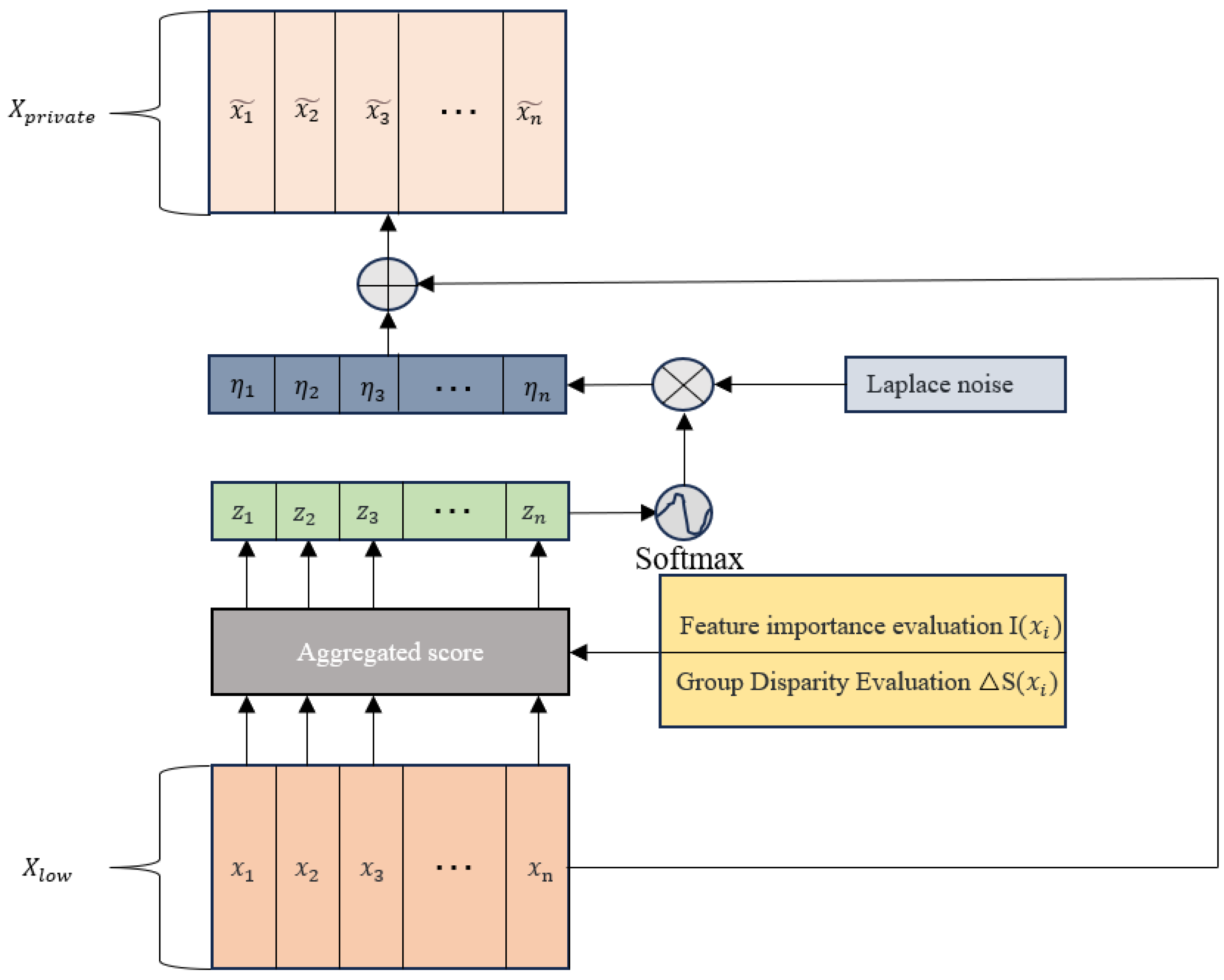

- We design a collaborative noise injection mechanism that combines self-attention with adaptive sensitivity optimization. Differential privacy noise is dynamically allocated according to feature importance and inter-group disparities, which allows AMF-DP to protect sensitive information while maintaining accuracy and fairness for different demographic groups.

- 3.

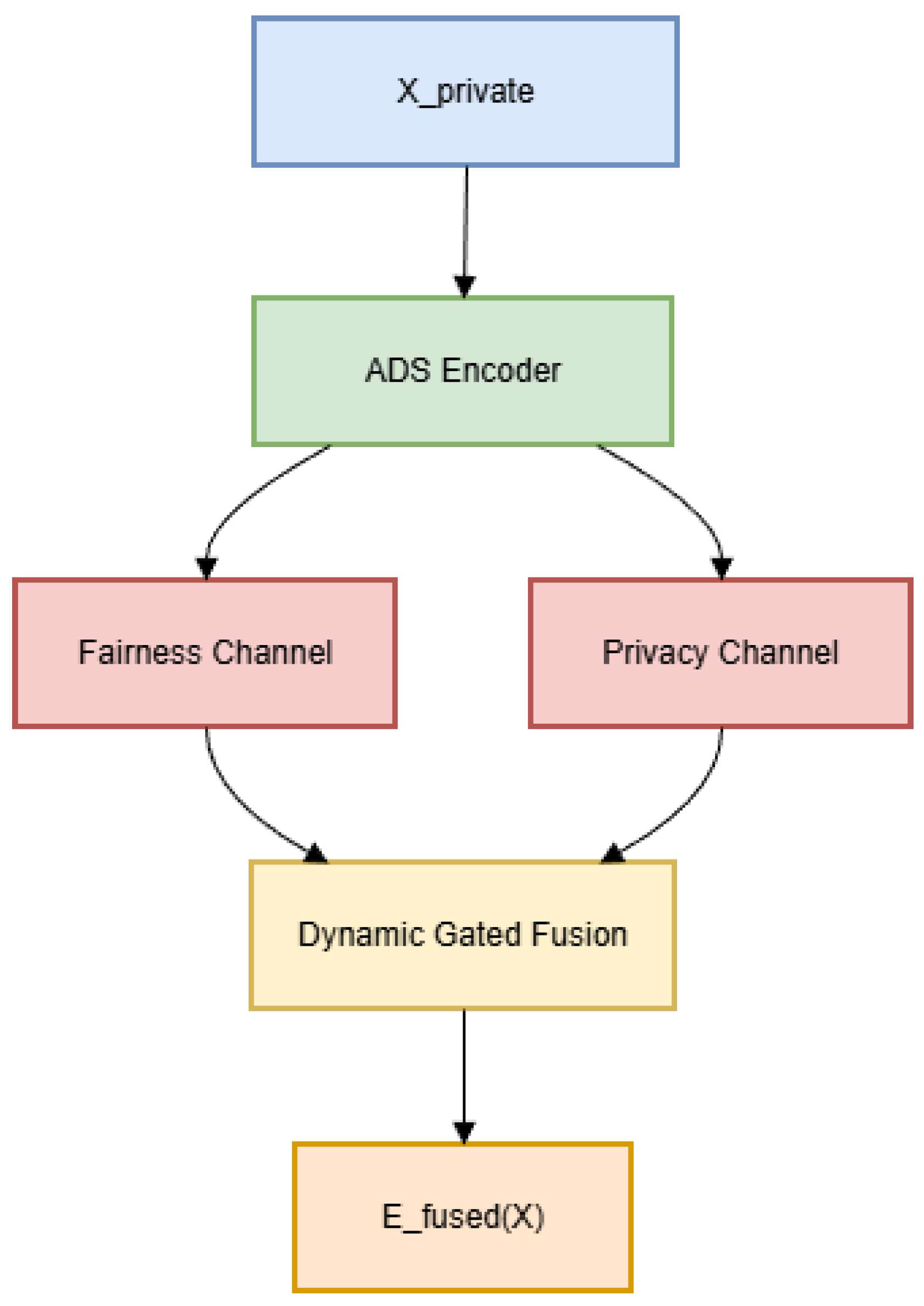

- We introduce an adaptive dual-stream (ADS) encoder that processes fairness-related and privacy-related features in two parallel streams and fuses them through a dynamic gating module. This design enables fine-grained control over the trade-off between performance, fairness, and privacy, and leads to a more balanced solution than existing single-stream DP or fairness methods.

- 4.

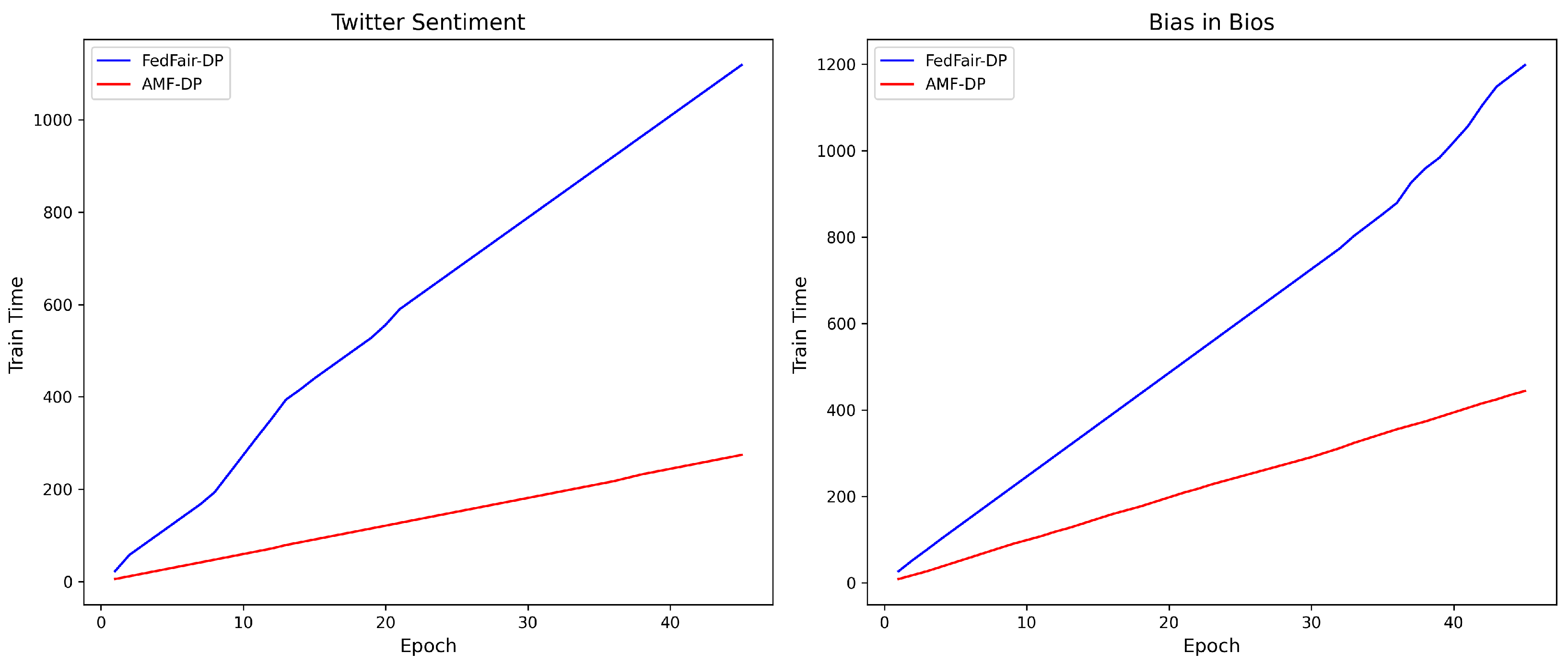

- From a practical point of view, AMF-DP acts as a plug-and-play encoder for standard Transformer-based text classifiers. It provides a concrete training recipe and evaluation protocol for jointly optimizing accuracy, TPR-gap/GRMS, Leakage, and MDL. Extensive experiments on three public datasets show that AMF-DP consistently reduces fairness gaps and sensitive-attribute leakage while keeping accuracy and training cost at a level comparable to strong baselines such as FedFair-DP, making it suitable for real-world text classification systems with multi-objective requirements.

2. Related Work

2.1. DP in Text Representation Learning

2.2. Fairness Optimization in NLP Models

2.3. Privacy–Fairness Joint Optimization

3. Approach

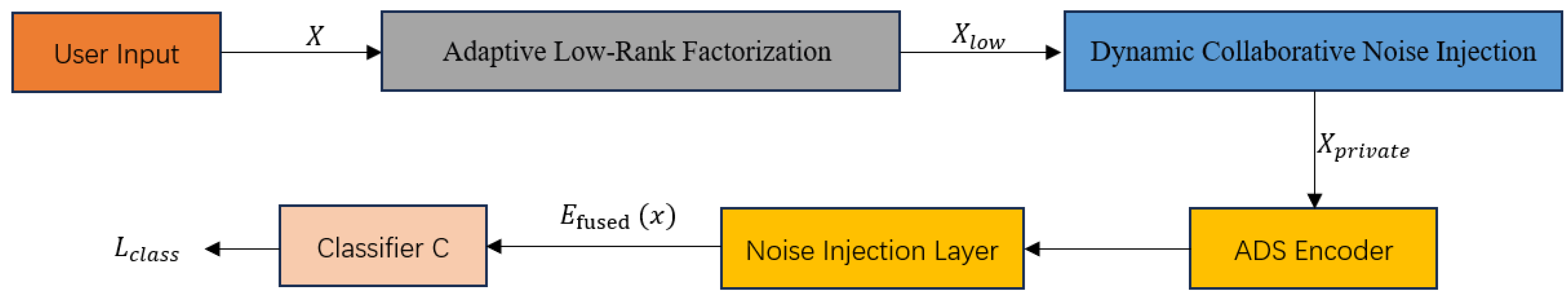

3.1. Model Overview

| Algorithm 1 Training procedure of AMF-DP |

|

3.2. Adaptive Low-Rank Embedding Learning

3.3. Collaborative Noise Injection

3.4. Adaptive Dual-Stream Encoder

4. Experiment

4.1. Experimental Setup

- (1)

- Twitter Sentiment [37]: comprising 200,000 tweets annotated with binary sentiment labels and race-related attributes (speakers of African American English and Standard American English);

- (2)

- Bias in Bios [38] dataset: contains 393,423 text biographies, annotated with occupational labels (28 categories) and binary gender attributes.

- (3)

- Adult Income [39]: This dataset is derived from a subset of the 1994 U.S. Census database, containing 48,842 records, each with 14 features including age, education level, occupation, race, gender, etc., and annotated with a binary classification label indicating whether annual income exceeds $50,000.

- Standard Text Classifier (STC): A traditional deep text classification model based on a Transformer-based classifier, without introducing any privacy protection or fairness constraints, with classification accuracy as the primary optimization objective. This method serves as a reference for the upper limit of performance.

- Fairness-Aware Classifier (FAIR): A representational fairness optimization method that introduces a group fairness regularization term into the loss function to reduce the correlation between model predictions and sensitive attributes (such as gender, race, etc.) [42]. This method reflects the trade-off between fairness and performance.

- Differential Privacy Classifier (DP): This method uses differential privacy mechanisms (DP-SGD, [43]) to inject noise into the model parameter update process, thereby protecting the privacy of training data. This method is used to evaluate changes in model performance and fairness under different privacy protection strengths.

- Adversarial Debiasing (ADV): Combines fairness enhancement methods from adversarial training (e.g., Zhang et al., 2018) with the introduction of a sensitive attribute discriminator to force the main model to learn feature representations independent of sensitive attributes, thereby enhancing fairness [11]. This method focuses on fairness enhancement but has high computational costs.

- Privacy-Preserving Matrix Factorization (PMF): This method employs privacy-preserving matrix factorization to perform low-rank embedding on input features while injecting noise, balancing feature representation capability with privacy protection [44]. This method is used to compare the ability of different matrix factorization strategies to balance privacy and performance.

- Federated Fairness with DP (FedFair-DP): A method combining adversarial training and differential privacy, which enhances fairness and privacy protection in a distributed environment through a differential privacy encoder and adversarial training [32]. This method reflects the latest advancements in multi-objective optimization.

- AMF-DP (the method in this paper): the adaptive matrix factorization-differential privacy method proposed in the paper incorporates multi-objective optimization, dynamic noise injection, and dual-stream coding mechanism to systematically improve the model performance, fairness, and privacy protection.

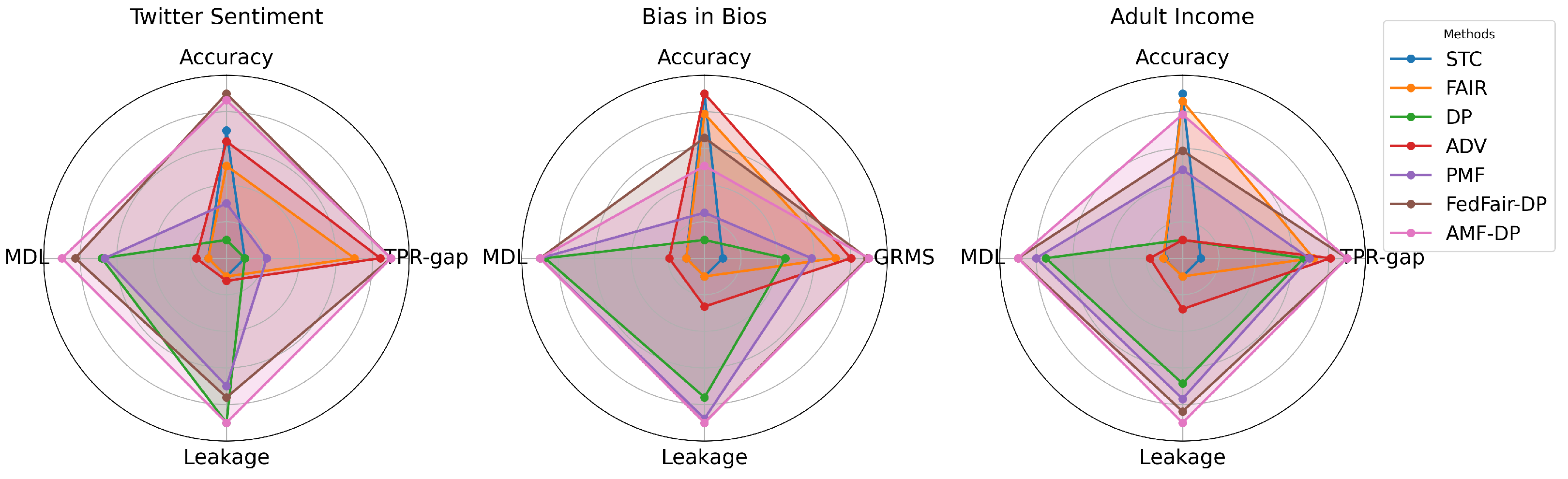

4.2. Analysis

4.2.1. Performance Analysis

4.2.2. Trade-Off Analysis

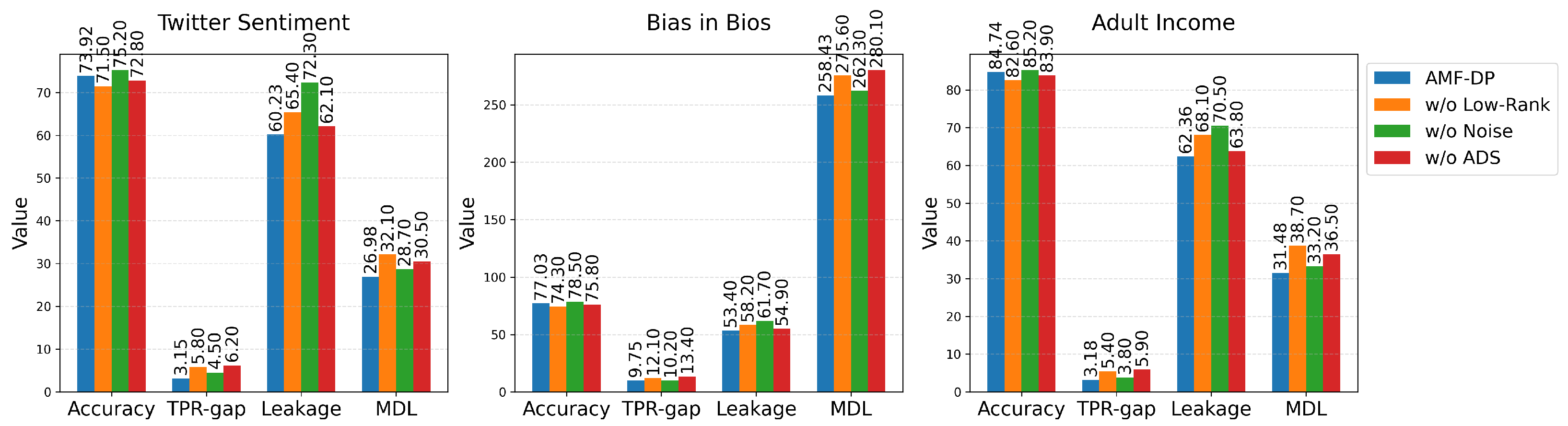

4.3. Ablation Experiment

4.4. Practical Applications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, H.; Xu, M.; Song, Y. Sentence embedding leaks more information than you expect: Generative embedding inversion attack to recover the whole sentence. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.03010. [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, E.; Jain, S.; Pichotta, K.; Goldberg, Y.; Wallace, B.C. Does BERT pretrained on clinical notes reveal sensitive data? arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.07762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Zhang, M.; Ji, S.; Yang, M. Privacy risks of general-purpose language models. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–20 May 2020; pp. 1314–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, T.; Gaut, A.; Tang, S.; Huang, Y.; Elsherief, M.; Zhao, J.; Mirza, D.; Belding-Royer, E.M.; Chang, K.-W.; Wang, W.Y. Mitigating Gender Bias in Natural Language Processing: Literature Review. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.08976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, A.; Baranowska, N.N.; Dennis, M.J.; Graus, D.; Hacker, P.; Saldivar, J.; Zuiderveen Borgesius, F.J.; Biega, A.J. Fairness and Bias in Algorithmic Hiring: A Multidisciplinary Survey. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2023, 16, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, J.L.; Choma, M.A.; Onofrey, J.A. Bias in medical AI: Implications for clinical decision-making. PLoS Digit. Health 2024, 3, e0000651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, N.; Jin, R.; Thai, M.T.; Hu, H.; Dou, D. Preserving Differential Privacy in Adversarial Learning with Provable Robustness. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.09822. [Google Scholar]

- Panda, A.; Wu, T.; Wang, J.T.; Mittal, P. Privacy-Preserving In-Context Learning for Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bagdasarian, E.; Shmatikov, V. Differential Privacy Has Disparate Impact on Model Accuracy. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.12101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Ding, M.; Qu, Y.; Ni, W.; Smith, D.; Rakotoarivelo, T. Privacy at a Price: Exploring its Dual Impact on AI Fairness. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.09391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Lemoine, B.; Mitchell, M. Mitigating Unwanted Biases with Adversarial Learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–3 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, Y.; Lee, K.; Whang, S.E.; Suh, C. FairBatch: Batch Selection for Model Fairness. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.01696. [Google Scholar]

- Lahoti, P.; Beutel, A.; Chen, J.; Lee, K.; Prost, F.; Thain, N.; Wang, X.; Chi, E.H. Fairness without Demographics through Adversarially Reweighted Learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.13114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.; Yu, J.; Nandakumar, K.; Li, Y.; Ma, X.; Jin, J.; Yu, H.; Ng, K.S. Towards Fair and Privacy-Preserving Federated Deep Models. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2019, 31, 2524–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ge, Y.; Su, C.; Wang, D.; Zhao, X.; Ying, Y. Fairness-aware Differentially Private Collaborative Filtering. In Proceedings of the WWW ’23 Companion: Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, Austin, TX, USA, 30 April–4 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ghoukasian, H.; Asoodeh, S. Differentially Private Fair Binary Classifications. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory (ISIT), Athens, Greece, 7–12 July 2024; pp. 611–616. [Google Scholar]

- Staab, R.; Vero, M.; Balunović, M.; Vechev, M. Beyond Memorization: Violating Privacy via Inference with Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.07298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi, B.; Huang, Y.; Kamath, P.; Kumar, R.; Manurangsi, P.; Sinha, A.; Zhang, C. Sparsity-Preserving Differentially Private Training of Large Embedding Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.08357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.; Shamsabadi, A.S.; Ashurst, C.; Weller, A. Identifying and Mitigating Privacy Risks Stemming from Language Models: A Survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.01424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Meng, X.; Liu, X. Differentially Private Recurrent Variational Autoencoder for Text Privacy Preservation. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2023, 28, 1565–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.C.C.D.; Ferraz, T.P.; Lopes, R.D.D. Enriching GNNs with Text Contextual Representations for Detecting Disinformation Campaigns on Social Media. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.19193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, W.; Yu, P. Privacy and Fairness in Federated Learning: On the Perspective of Tradeoff. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Chen, Y.; Wang, B.; Cao, J.; Li, F. Utility-Aware Exponential Mechanism for Personalized Differential Privacy. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 25–28 May 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Blodgett, S.L.; Barocas, S.; Daumé, H.; Wallach, H.M. Language (Technology) is Power: A Critical Survey of “Bias” in NLP. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.14050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravfogel, S.; Elazar, Y.; Gonen, H.; Twiton, M.; Goldberg, Y. Null It Out: Guarding Protected Attributes by Iterative Nullspace Projection. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), Seattle, WA, USA, 5–10 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Xu, C.; Yao, C.; Liang, S.; Wu, Y.; Liang, D.; Liu, X.; Liu, A. Improving Robust Fairness via Balance Adversarial Training. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.07534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Z.; Han, B.; Liu, Y. Understanding Fairness Surrogate Functions in Algorithmic Fairness. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.11211. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Jiang, J.; Sun, Z.; Chen, J. A Large-Scale Empirical Study on Improving the Fairness of Image Classification Models. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis, Vienna, Austria, 15–19 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, J.X.C.; DhakshinaMurthy, A.; George, R.B.; Branco, P. The Effect of Resampling Techniques on the Performances of Machine Learning Clinical Risk Prediction Models in the Setting of Severe Class Imbalance: Development and Internal Validation in a Retrospective Cohort. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2024, 4, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Li, D.; Zhao, C.; Wu, X.; Tian, Q.; Shao, M. Supervised Algorithmic Fairness in Distribution Shifts: A Survey. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 3–9 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Palakkadavath, R.; Le, H.; Nguyen-Tang, T.; Gupta, S.; Venkatesh, S. Fair Domain Generalization with Heterogeneous Sensitive Attributes Across Domains. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Tucson, AZ, USA, 26 February–6 March 2025; pp. 7389–7398. [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari, G.; Denis, P.; Keller, M.; Bellet, A. Fair NLP Models with Differentially Private Text Encoders. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.06135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagdasaryan, E.; Poursaeed, O.; Shmatikov, V. Differential Privacy Has Disparate Impact on Model Accuracy. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (NeurIPS 2019); Wallach, H., Larochelle, H., Beygelzimer, A., d’Alché-Buc, F., Fox, E., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 15479–15488. [Google Scholar]

- Koren, Y.; Bell, R.; Volinsky, C. Matrix Factorization Techniques for Recommender Systems. Computer 2009, 42, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Krishnan, R.G.; Hoffman, M.D.; Jebara, T. Variational Autoencoders for Collaborative Filtering. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference (WWW), Lyon, France, 23–27 April 2018; pp. 689–698. [Google Scholar]

- Sedhain, S.; Menon, A.K.; Sanner, S.; Xie, L. AutoRec: Autoencoders Meet Collaborative Filtering. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW), Florence, Italy, 18–22 May 2015; pp. 111–112. [Google Scholar]

- Blodgett, S.L.; Green, L.; O’Connor, B. Demographic Dialectal Variation in Social Media: A Case Study of African-American English. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1608.08868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Arteaga, M.; Romanov, A.; Wallach, H.; Chayes, J.; Borgs, C.; Chouldechova, A.; Geyik, S.; Kenthapadi, K.; Kalai, A.T. Bias in Bios: A Case Study of Semantic Representation Bias in a High-Stakes Setting. In Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT), Atlanta, GA, USA, 29–31 January 2019; pp. 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kohavi, R. Scaling Up the Accuracy of Naive-Bayes Classifiers: A Decision-Tree Hybrid. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD), Portland, OR, USA, 2–4 August 1996; Volume 96, pp. 202–207. [Google Scholar]

- Romanov, A.; De-Arteaga, M.; Wallach, H.; Chayes, J.; Borgs, C.; Chouldechova, A.; Geyik, S.; Kenthapadi, K.; Rumshisky, A.; Kalai, A.T. What’s in a Name? Reducing Bias in Bios without Access to Protected Attributes. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.05233. [Google Scholar]

- Voita, E.; Titov, I. Information-Theoretic Probing with Minimum Description Length. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.12298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, L.; Wu, X. FairGAN: Fairness-Aware Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Seattle, WA, USA, 10–13 December 2018; pp. 570–575. [Google Scholar]

- Abadi, M.; Chu, A.; Goodfellow, I.; McMahan, H.B.; Mironov, I.; Talwar, K.; Zhang, L. Deep Learning with Differential Privacy. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS), Vienna, Austria, 24–28 October 2016; pp. 308–318. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, J.; Xia, C.; Zhong, S. Differentially Private Matrix Factorization. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), Buenos Aires, Argentina, 25–31 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | Method | Accuracy ↑ | Gap/GRMS ↓ | Leakage ↓ | MDL ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Twitter Sentiment | STC | 73.13 | 26.63 | 86.73 | 15.77 |

| FAIR | 72.21 | 11.82 | 85.92 | 16.05 | |

| DP | 69.80 | 28.75 | 61.15 | 23.42 | |

| ADV | 72.85 | 7.21 | 83.44 | 17.63 | |

| PMF | 71.23 | 23.10 | 68.20 | 23.24 | |

| FedFair-DP | 74.57 | 4.47 | 66.56 | 25.05 | |

| AMF-DP | 73.92 | 3.15 | 60.23 | 26.98 | |

| Bias in Bios | STC | 79.52 | 17.04 | 78.20 | 173.66 |

| FAIR | 78.63 | 11.81 | 77.36 | 180.43 | |

| DP | 75.30 | 18.84 | 60.32 | 237.55 | |

| ADV | 79.20 | 9.01 | 68.64 | 190.02 | |

| PMF | 76.35 | 15.12 | 57.44 | 243.79 | |

| FedFair-DP | 78.08 | 10.54 | 55.67 | 255.52 | |

| AMF-DP | 77.43 | 8.14 | 53.40 | 257.43 | |

| Adult Income | STC | 85.42 | 17.81 | 84.21 | 19.13 |

| FAIR | 84.97 | 7.33 | 83.12 | 20.42 | |

| DP | 82.56 | 8.11 | 69.24 | 28.37 | |

| ADV | 82.24 | 5.97 | 78.13 | 21.33 | |

| PMF | 83.78 | 7.66 | 67.41 | 29.02 | |

| FedFair-DP | 84.11 | 4.23 | 65.90 | 30.25 | |

| AMF-DP | 84.74 | 3.18 | 62.36 | 31.48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, C.; Dai, M.; Guan, Z.; Ye, Z.; Hou, Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, H. Adaptive Feature Representation Learning for Privacy-Fairness Joint Optimization. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13031. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413031

Ma C, Dai M, Guan Z, Ye Z, Hou Y, Wang X, Huang H. Adaptive Feature Representation Learning for Privacy-Fairness Joint Optimization. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13031. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413031

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Chao, Mingkai Dai, Zhibo Guan, Zi Ye, Yikai Hou, Xiaoyu Wang, and Hai Huang. 2025. "Adaptive Feature Representation Learning for Privacy-Fairness Joint Optimization" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13031. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413031

APA StyleMa, C., Dai, M., Guan, Z., Ye, Z., Hou, Y., Wang, X., & Huang, H. (2025). Adaptive Feature Representation Learning for Privacy-Fairness Joint Optimization. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13031. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413031