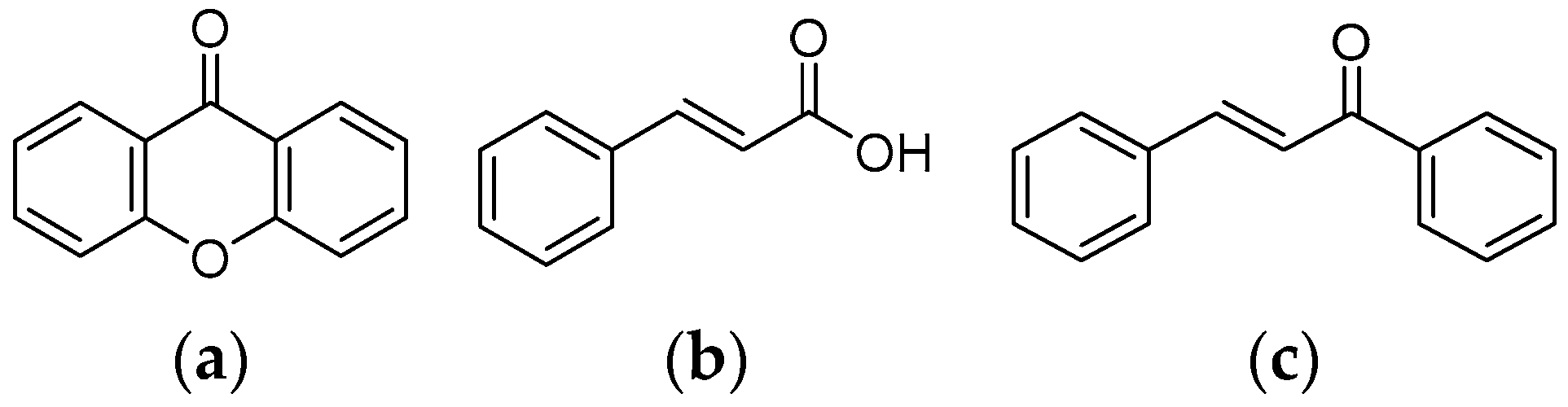

Ecotoxicological Evaluation of Simple Xanthone, Cinnamic Acid, and Chalcone Derivatives Using the Microtox Assay for Sustainable Synthetic Design of Biologically Active Molecules

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characteristic of the Tested Compounds

2.2. Microtox Assay

2.3. In Silico Ecotoxicity Evaluation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Sun, D.; Li, H.; Chen, L. A Review on Natural Products with Cage-like Structure. Bioorganic Chem. 2022, 128, 106106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shen, J.; Zhu, K. Antibacterial Activities of Plant-Derived Xanthones. RSC Med. Chem. 2022, 13, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oriola, A.O.; Kar, P. Naturally Occurring Xanthones and Their Biological Implications. Molecules 2024, 29, 4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, T.; Das, T.; Gopalakrishnan, A.V.; Saha, S.C.; Ghorai, M.; Nandy, S.; Kumar, M.; Radha; Ghosh, A.; Mukerjee, N.; et al. Mangiferin: The Miraculous Xanthone with Diverse Pharmacological Properties. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2023, 396, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, N.V.; Teh, S.S.; Lim, Y.M.; Mah, S.H. Natural Xanthones and Skin Inflammatory Diseases: Multitargeting Mechanisms of Action and Potential Application. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 594202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Guan, T.; Wang, S.; Zhou, C.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, K.; Han, X.; Lin, J.; Tang, Q.; et al. Novel Xanthone Antibacterials: Semi-Synthesis, Biological Evaluation, and the Action Mechanisms. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2023, 83, 117232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelaszczyk, D.; Lipkowska, A.; Szkaradek, N.; Słoczyńska, K.; Gunia-Krzyżak, A.; Librowski, T.; Marona, H. Synthesis and Preliminary Anti-Inflammatory Evaluation of Xanthone Derivatives. Heterocycl. Commun. 2018, 24, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Guo, J.; Cheng, M.; Zhou, W.; Wan, Y.; Wang, R.; Fang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Liu, J.; Xie, S.S. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Novel Xanthone-Alkylbenzylamine Hybrids as Multifunctional Agents for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 213, 113154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szkaradek, N.; Gunia, A.; Waszkielewicz, A.M.; Antkiewicz-Michaluk, L.; Cegła, M.; Szneler, E.; Marona, H. Anticonvulsant Evaluation of Aminoalkanol Derivatives of 2- and 4-Methylxanthone. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 1190–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat, M.; Popiół, J.; Gunia-Krzyżak, A. Cinnamic Acid Derivatives as Potential Multifunctional Agents in Cosmetic Formulations Used for Supporting the Treatment of Selected Dermatoses. Molecules 2024, 29, 5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gryko, K.; Kalinowska, M.; Ofman, P.; Choińska, R.; Świderski, G.; Świsłocka, R.; Lewandowski, W. Natural Cinnamic Acid Derivatives: A Comprehensive Study on Structural, Anti/pro-Oxidant, and Environmental Impacts. Materials 2021, 14, 6098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ran, M.; Wang, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, S.; Yu, Y. Structure-Activity Relationships of Antityrosinase and Antioxidant Activities of Cinnamic Acid and Its Derivatives. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2021, 85, 1697–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulos, I.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D. Approaches for the Discovery of Cinnamic Acid Derivatives with Anticancer Potential. Expert. Opin. Drug Discov. 2024, 19, 1281–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Li, G.; Zheng, G.; Yu, C. Design and Synthesis of Cinnamic Acid Triptolide Ester Derivatives as Potent Antitumor Agents and Their Biological Evaluation. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 67, 128760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouni, C.; Theodosis-Nobelos, P.; Rekka, E.A. Antioxidant and Hypolipidemic Activities of Cinnamic Acid Derivatives. Molecules 2023, 28, 6732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunia-Krzyżak, A.; Popiół, J.; Słoczyńska, K.; Żelaszczyk, D.; Koczurkiewicz-Adamczyk, P.; Wójcik-Pszczoła, K.; Bucki, A.; Sapa, M.; Kasza, P.; Borczuch-Kostańska, M.; et al. Discovery of (E)-3-(4-Chlorophenyl)-N-(5-Hydroxypentyl)Acrylamide among N-Substituted Cinnamamide Derivatives as a Novel Cosmetic Ingredient for Hyperpigmentation. Bioorganic Chem. 2024, 150, 107533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat, M.; Gunia-Krzyżak, A. Cinnamic Acid Derivatives as Potential Melanogenesis Inhibitors for Use in Cosmetic Products. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 18, e00767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, X.; Wu, H.; Tang, G. Design, Synthesis, and Activity Study of Cinnamic Acid Derivatives as Potent Antineuroinflammatory Agents. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Cai, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Ma, Z.; Feng, J.; Liu, X.; Lei, P. Discovery of Novel Cinnamic Acid Derivatives as Fungicide Candidates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 2492–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.P.; Rai, H.; Singh, G.; Singh, G.K.; Mishra, S.; Kumar, S.; Srikrishna, S.; Modi, G. A Review on Ferulic Acid and Analogs Based Scaffolds for the Management of Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 215, 113278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitulescu, G.; Lupuliasa, D.; Adam-Dima, I.; Nitulescu, G.M. Ultraviolet Filters for Cosmetic Applications. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, R.; Mousavi, S.; Alazmi, M.; Saleem, R.S.Z. A Comprehensive Review of Aminochalcones. Molecules 2020, 25, 5381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasim, H.A.; Nahar, L.; Jasim, M.A.; Moore, S.A.; Ritchie, K.J.; Sarker, S.D. Chalcones: Synthetic Chemistry Follows Where Nature Leads. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Fu, X.; Sun, S.; Wu, Q. Chalcone Derivatives: Role in Anticancer Therapy. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, P.S.; Bibá, G.C.C.; Melo, E.D.D.N.; Muzitano, M.F. Chalcones against the Hallmarks of Cancer: A Mini-Review. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 4809–4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, M.A.; Rizk, S.A.; Fahim, A.M. Synthesis, Reactions and Application of Chalcones: A Systematic Review. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 5317–5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abonia, R.D.; Castillo, J.; Insuasty, B.; Quiroga, J.; El Nogueras, M.; Cobo, J. Synthesis of Novel Quinoline-2-One Based Chalcones of Potential Anti-Tumor Activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 57, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, C.; Zhang, L.; Sun, B.; Cui, Y.; Sang, F. Isolation and Biological Activity of Natural Chalcones Based on Antibacterial Mechanism Classification. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2023, 93, 117454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.W.; He, L.Y.; Zhang, S.S.; He, Z.W.; Liu, W.H.; Zhang, L.; Guan, L.P.; Wang, S.H. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Activity of Chalcone Analogs Containing 4-Phenylquinolin and Benzohydrazide. Chem. Biodivers. 2022, 19, e202100610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapa, P.; Upadhyay, S.P.; Suo, W.Z.; Singh, V.; Gurung, P.; Lee, E.S.; Sharma, R.; Sharma, M. Chalcone and Its Analogs: Therapeutic and Diagnostic Applications in Alzheimer’s Disease. Bioorganic Chem. 2021, 108, 104681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahssay, S.W.; Hailu, G.S.; Desta, K.T. Design, Synthesis, Characterization and in Vivo Antidiabetic Activity Evaluation of Some Chalcone Derivatives. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, 15, 3119–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wydro, U.; Wołejko, E.; Luarasi, L.; Puto, K.; Tarasevičienė, Ž.; Jabłońska-Trypuć, A. A Review on Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products Residues in the Aquatic Environment and Possibilities for Their Remediation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, O.J.; Lin, C.; Jeng, F.; Shih, C. A Review of Microtox Test and Its Applications. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 1995, 52, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielka, E.; Siedlecka, A.; Wolf, M.; Stróżak, S.; Piekarska, K.; Strub, D. Ecotoxicity Assessment of Camphor Oxime Using Microtox Assay—Preliminary Research. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences, Les Ulis, France, 24 August 2018; EDP Sciences: London, UK, 2018. Volume 44. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B.T. Microtox® Acute Toxicity Test. In Small-Scale Freshwater Toxicity Investigations; Blaise, C., Férard, J.F., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 1, pp. 69–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunia-Krzyżak, A.; Popiół, J.; Słoczyńska, K.; Żelaszczyk, D.; Orzeł, K.; Koczurkiewicz-Adamczyk, P.; Wójcik-Pszczoła, K.; Kasza, P.; Borczuch-Kostańska, M.; Pękala, E. In Silico and in Vitro Evaluation of a Safety Profile of a Cosmetic Ingredient: 4-Methoxychalcone (4-MC). Toxicol. Vitr. 2023, 93, 105696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sova, M. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of cinnamic acid derivatives. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 749–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, H.; Xu, Q.; Guo, H.Y.; Huang, X.; Chen, F.; Jin, L.; Quan, Z.S.; Shen, Q.K. Application of Cinnamic Acid in the Structural Modification of Natural Products: A Review. Phytochemistry 2023, 206, 113532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Y.S.; Liu, J.Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Liu, Z.; Quan, Z.S.; Wang, S.H.; Yin, X.M. Application of Chalcone in the Structural Modification of Natural Products: An Overview. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e202401953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popiół, J.; Gunia-Krzyżak, A.; Słoczyńska, K.; Koczurkiewicz-Adamczyk, P.; Piska, K.; Wójcik-Pszczoła, K.; Żelaszczyk, D.; Krupa, A.; Żmudzki, P.; Marona, H.; et al. The Involvement of Xanthone and (E)-Cinnamoyl Chromophores for the Design and Synthesis of Novel Sunscreening Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, H.; Liu, H.; Schlenk, D.; Mu, J.; Lacorte, S.; Ying, G.G.; Xie, L. Anticancer Drugs in the Aquatic Ecosystem: Environmental Occurrence, Ecotoxicological Effect and Risk Assessment. Environ. Int. 2021, 153, 106543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejna, M.; Kapuścińska, D.; Aksmann, A. Pharmaceuticals in the Aquatic Environment: A Review on Eco-Toxicology and the Remediation Potential of Algae. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liliana, A.; Ríos, M.; Gutierrez-Suarez, K.; Carmona, Z.; Ramos, G.; Felipe, L.; Oliveira, S. Pharmaceuticals as Emerging Pollutants: Case Naproxen an Overview. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzyn, A.; Popiół, J.; Gunia-Krzyżak, A.; Żelaszczyk, D.; Dąbrówka, B.; Koczurkiewicz-Adamczyk, P.; Piska, K.; Żmudzki, P.; Pękala, E.; Słoczyńska, K. Biotransformation of Oxybenzone and 3-(4-Methylbenzylidene)Camphor in Cunninghamella Species: Potential for Environmental Clean-up of Widely Used Sunscreen Agents. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 489, 137544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, D.; Sinha, R. Physiological Impact of Personal Care Product Constituents on Non-Target Aquatic Organisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, S.; Luetjens, L.H.; Preibisch, A.; Acker, S.; Petersen-Thiery, M. Cosmetic UV Filters in the Environment—State of the Art in EU Regulations, Science and Possible Knowledge Gaps. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2023, 45, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczyk, A.; Bownik, A.; Dudka, J.; Kowal, K.; Ślaska, B. Daphnia Magna Model in the Toxicity Assessment of Pharmaceuticals: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 763, 143038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Martyniuk, C.J.; Simmons, D.B.D. Current Topics in Omics, Ecotoxicology, and Environmental Science. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part. D Genom. Proteom. 2021, 38, 100782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, F.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, K.; Lan, S.; Yang, W.; Gan, X. Eco-Friendly Cinnamic Acid Derivatives Containing Glycoside Scaffolds as Potential Antiviral Agents. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 17752–17762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidaurre, R.; Bramke, I.; Puhlmann, N.; Owen, S.F.; Angst, D.; Moermond, C.; Venhuis, B.; Lombardo, A.; Kümmerer, K.; Sikanen, T.; et al. Design of Greener Drugs: Aligning Parameters in Pharmaceutical R&D and Drivers for Environmental Impact. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 104022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.; Sanderson, H.; Roy, K.; Benfenati, E.; Leszczynski, J. Green Chemistry in the Synthesis of Pharmaceuticals. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 3637–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenari, F.; Molnár, S.; Perjési, P. Reaction of Chalcones with Cellular Thiols. The Effect of the 4-Substitution of Chalcones and Protonation State of the Thiols on the Addition Process. Diastereoselective Thiol Addition. Molecules 2021, 26, 4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P.A.; Widen, J.C.; Harki, D.A.; Brummond, K.M. Covalent Modifiers: A Chemical Perspective on the Reactivity of α,β-Unsaturated Carbonyls with Thiols via Hetero-Michael Addition Reactions. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 839–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, T.W.; Carlson, R.E.; Cronin, M.T.D.; Hermens, J.L.M.; Johnson, R.; O’Brien, P.J.; Roberts, D.W.; Siraki, A.; Wallace, K.B.; Veith, G.D. A Conceptual Framework for Predicting the Toxicity of Reactive Chemicals: Modeling Soft Electrophilicity. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2006, 17, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarbrough, J.W.; Schultz, T.W. Abiotic Sulfhydryl Reactivity: A Predictor of Aquatic Toxicity for Carbonyl-Containing α,β-Unsaturated Compounds. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007, 20, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, F.N.; Vivian, D.N.; Raimondo, S.; Tebes-Stevens, C.T.; Barron, M.G. Relationships Between Aquatic Toxicity, Chemical Hydrophobicity, and Mode of Action: Log Kow Revisited. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2022, 83, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, C.; Zhang, W.; Sheng, C.; Zhang, W.; Xing, C.; Miao, Z. Chalcone: A Privileged Structure in Medicinal Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 7762–7810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas-Boas, C.; Sousa, J.; Lima, E.; Running, L.; Resende, D.; Ribeiro, A.R.L.; Sousa, E.; Santos, M.M.; Aga, D.S.; Tiritan, M.E.; et al. Preliminary Hazard Assessment of a New Nature-Inspired Antifouling (NIAF) Agent. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 933, 172824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas-Boas, C.; Silva, E.R.; Resende, D.; Pereira, B.; Sousa, G.; Pinto, M.; Almeida, J.R.; Correia-da-Silva, M.; Sousa, E. 3,4-Dioxygenated Xanthones as Antifouling Additives for Marine Coatings: In Silico Studies, Seawater Solubility, Degradability, Leaching, and Antifouling Performance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 68987–68997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazry, S.; Noordin, M.A.M.; Sanusi, S.; Noor, M.M.; Aizat, W.M.; Lazim, A.M.; Dyari, H.R.E.; Jamar, N.H.; Remali, J.; Othman, B.A.; et al. Cytotoxicity and Toxicity Evaluation of Xanthone Crude Extract on Hypoxic Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Embryos. Toxics 2018, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

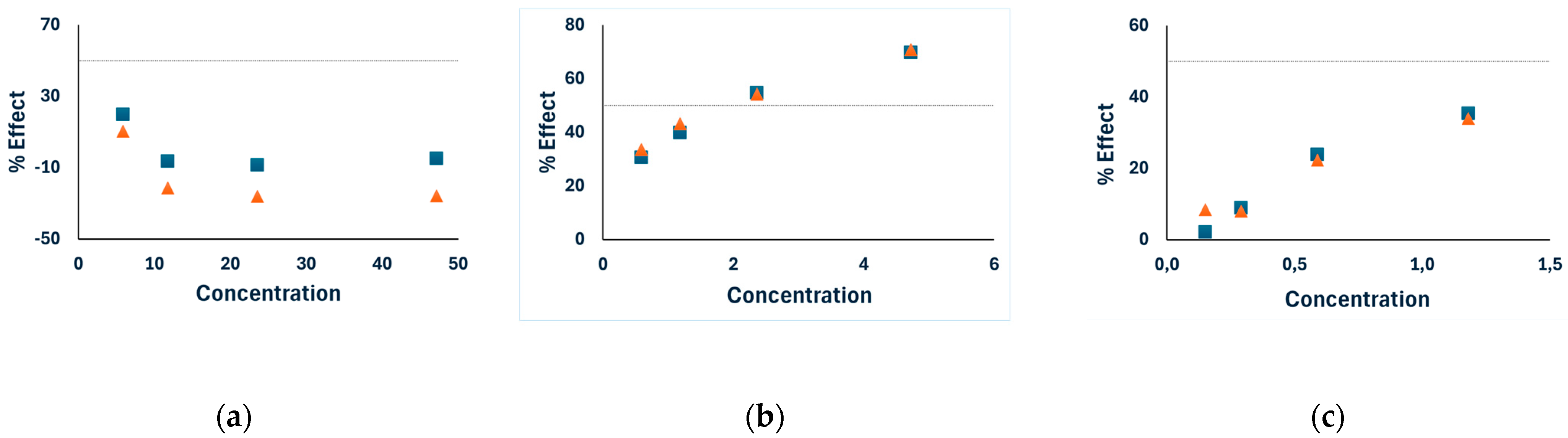

—results after 5 min incubation,

—results after 5 min incubation,  —results after 15 min incubation.

—results after 15 min incubation.

—results after 5 min incubation,

—results after 5 min incubation,  —results after 15 min incubation.

—results after 15 min incubation.

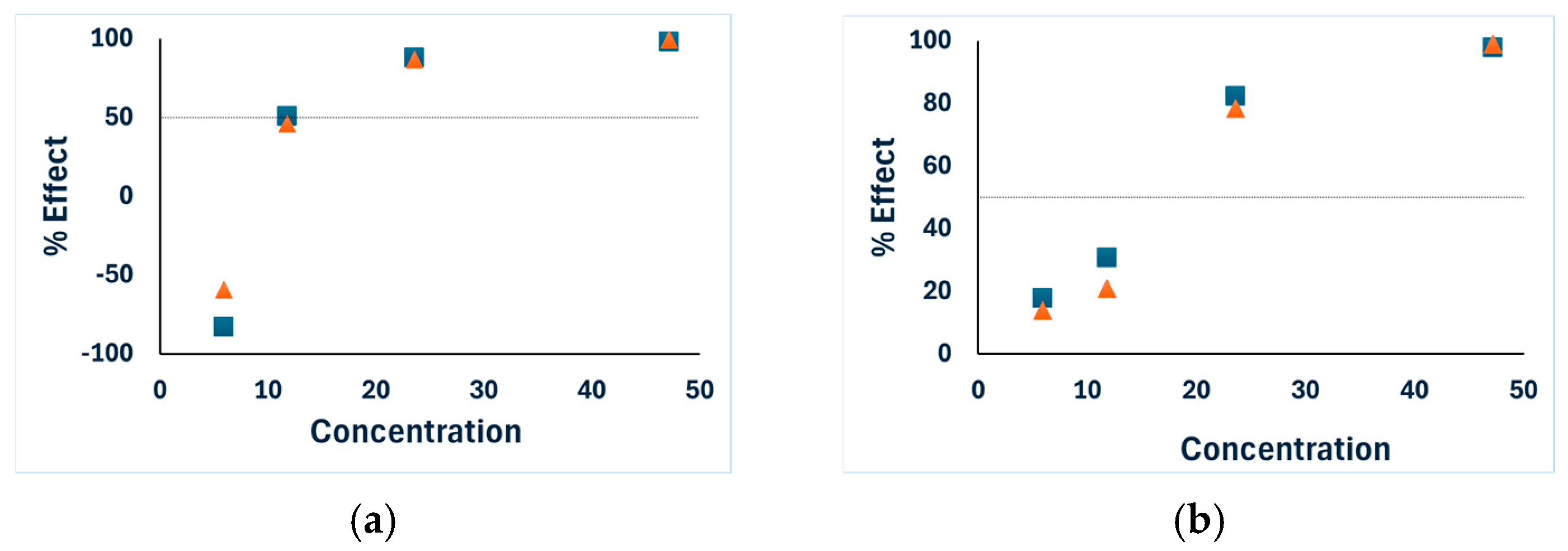

—results after 5 min incubation,

—results after 5 min incubation,  —results after 15 min incubation.

—results after 15 min incubation.

—results after 5 min incubation,

—results after 5 min incubation,  —results after 15 min incubation.

—results after 15 min incubation.

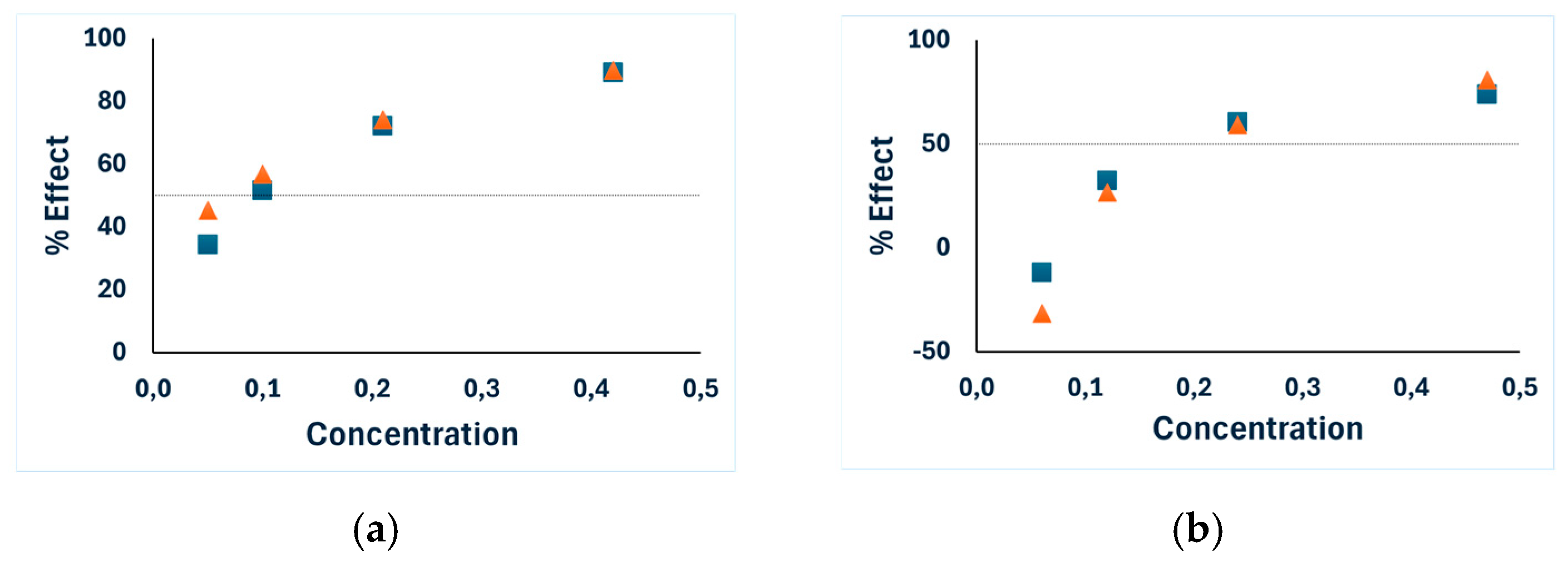

—results after 5 min incubation,

—results after 5 min incubation,  —results after 15 min incubation.

—results after 15 min incubation.

—results after 5 min incubation,

—results after 5 min incubation,  —results after 15 min incubation.

—results after 15 min incubation.

| Xanthone Derivative | EC50 mg/L (95% Confidence Range) * | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Chemical Structure | 5 min | 15 min |

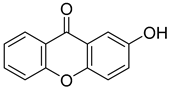

| 2-Hydroxy-9H-xanthen-9-one |  | 1.911 (1.440–2.537) | 1.648 (1.226–2.217) |

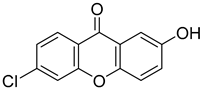

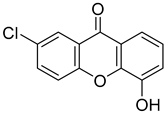

| 6-Chloro-2-hydroxy-9H-xanthen-9-one |  | 0.447 (0.080–2.499) | 0.818 (0.088–7.639) |

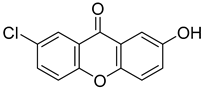

| 7-Chloro-2-hydroxy-9H-xanthen-9-one |  | 10.270 (2.349–44.860) | 11.200 (2.920–42.930) |

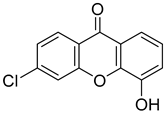

| 6-Chloro-4-hydroxy-9H-xanthen-9-one |  | 2.564 (1.166–5.637) | 1.799 (0.3043–10.64) |

| 7-Chloro-4-hydroxy-9H-xanthen-9-one |  | 12.460 (0.984–157.900) | Highest % effect: 35.16% (up to 23.58) |

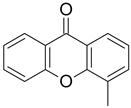

| 4-Methyl-9H-xanthen-9-one |  | 0.122 (0.041–0.361) | 0.085 (0.027–0.276) |

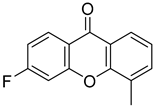

| 6-Fluoro-4-methyl-9H-xanthen-9-one |  | 1.203 (0.3883–3.728) | 1.226 (0.3065–4.907) |

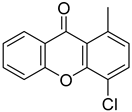

| 4-Chloro-1-methyl-9H-xanthen-9-one |  | Highest % effect: 30.19% (up to 47.15) | 22.870 (0.2595–2015) |

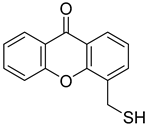

| 4-(Sulfanylmethyl)-9H-xanthen-9-one |  | 0.068 (0.023–0.197) | 0.231 (0.058–0.920) |

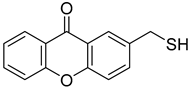

| 2-(Sulfanylmethyl)-9H-xanthen-9-one |  | Highest % effect: 19.66% (up to 47.15) | Highest % effect: 10.36% (up to 47.15) |

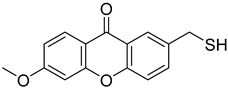

| 6-Methoxy-2-(sulfanylmethyl)-9H-xanthen-9-one |  | 2.122 (0.9054–4.974) | 1.203 (0.3038–4.766) |

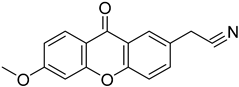

| (6-Methoxy-9-oxo-9H-xanthen-2-yl)acetonitrile |  | 1.113 (0.0262–47.32) | 2.845 (0.033–244.600) |

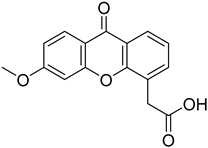

| (6-Methoxy-xanthen-4yl)-acetic acid |  | 8.718 (2.166–35.090) | 9.926 (1.547–63.710) |

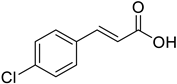

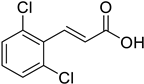

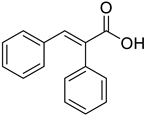

| Cinnamic Acid Derivative | EC50 mg/L (95% Confidence Range) * | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Chemical Structure | 5 min | 15 min |

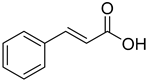

| (E)-Cinnamic acid |  | 11.97 (1.981–72.30) | 11.41 (1.752–75.45) |

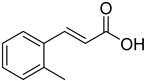

| (E)-2-Methylcinnamic acid |  | 8.48 (4.28–16.77) | 8.26 (2.16–31.63) |

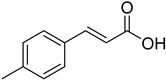

| (E)-4-Methylcinnamic acid |  | 11.87 (2.16–87.40) | 13.25 (1.26–94.55) |

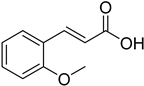

| (E)-2-Methoxycinnamic acid |  | 4.16 (0.46–37.23) | 19.65 (1.26–74.13) |

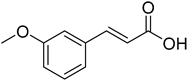

| (E)-3-Methoxycinnamic acid |  | 6.64 (3.74–11.77) | 7.58 (1.71–33.59) |

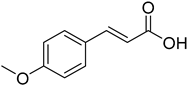

| (E)-4-Methoxycinnamic acid |  | 11.87 (0.02 to 902.40) | 13.25 (0.03 to 713.20) |

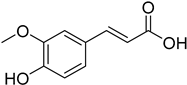

| (E)-4-Hydroxy-3-methoxycinnamic acid |  | 12.68 (7.545–21.32) | 13.76 (7.022–26.97) |

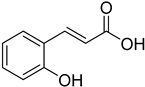

| (E)-2-Hydroxycinnamic acid |  | 14.08 (0.15–128.60) | 13.49 (0.13–98.56) |

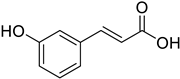

| (E)-3-Hydroxycinnamic acid |  | 16.45 (0.22 to 124.90) | Hormesis at 0–47.15 |

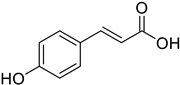

| (E)-4-Hydroxycinnamic acid |  | 11.64 (10.55–12.85) | 12.44 (7.25–21.47) |

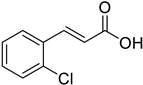

| (E)-2-Chlorocinnamic acid |  | 19.80 (8.176–47.95) | 20.84 (8.810–49.31) |

| (E)-4-Chlorocinnamic acid |  | 47.90 (19.52–90.17) | 40.92 (20.08–83.38) |

| (E)-2,6-Dichlorocinnamic acid |  | 26.87 (2.390–302.1) | 21.06 (2.856–155.3) |

| (E)-α-Phenyl cinnamic acid |  | 42.76 (2.158–847.4) | 37.97 (1.02–562.58) |

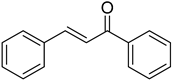

| Chalcone Derivative | EC50 mg/L (95% Confidence Range) * | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Chemical Structure | 5 min | 15 min |

| (E)-Chalcone |  | 0.115 (0.004–3.160) | 0.111 (0.005–2.451) |

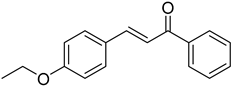

| (E)-4-Ethoxychalcone |  | 0.013 (0.012–0.014) | 0.005 (0.002–0.010) |

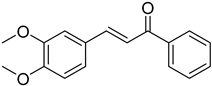

| (E)-3,4-Dimethoxychalcone |  | 0.0930 (0.0695–0.1244) | 0.073 (0.040–0.131) |

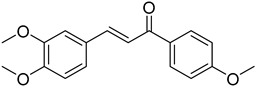

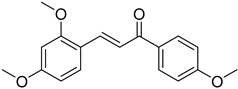

| (E)-3,4-Dimethoxy-4′-methoxychalcone |  | 0.097 (0.200–0.465) | 0.072 (0.006–0.858) |

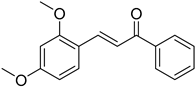

| (E)-2,4-Dimethoxychalcone |  | 0.255 (0.032–2.014) | 0.331 (0.031–3.562) |

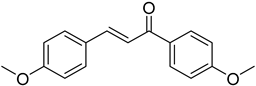

| (E)-4-Methoxy-4′-methoxychalcone |  | 0.205 (0.023–1.793) | 0.170 (0.023–1.257) |

| (E)-2,4-Dimethoxy-4′-methoxychalcone |  | 0.398 (0.160–0.992) | 0.392 (0.100–1.530) |

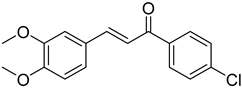

| (E)-3,4-Dimethoxy-4′-chlorochalcone |  | 0.196 (0.050–0.766) | 0.203 (0.119–0.348) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Żelaszczyk, D.; Gunia-Krzyżak, A.; Popiół, J.; Słoczyńska, K. Ecotoxicological Evaluation of Simple Xanthone, Cinnamic Acid, and Chalcone Derivatives Using the Microtox Assay for Sustainable Synthetic Design of Biologically Active Molecules. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12998. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412998

Żelaszczyk D, Gunia-Krzyżak A, Popiół J, Słoczyńska K. Ecotoxicological Evaluation of Simple Xanthone, Cinnamic Acid, and Chalcone Derivatives Using the Microtox Assay for Sustainable Synthetic Design of Biologically Active Molecules. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):12998. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412998

Chicago/Turabian StyleŻelaszczyk, Dorota, Agnieszka Gunia-Krzyżak, Justyna Popiół, and Karolina Słoczyńska. 2025. "Ecotoxicological Evaluation of Simple Xanthone, Cinnamic Acid, and Chalcone Derivatives Using the Microtox Assay for Sustainable Synthetic Design of Biologically Active Molecules" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 12998. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412998

APA StyleŻelaszczyk, D., Gunia-Krzyżak, A., Popiół, J., & Słoczyńska, K. (2025). Ecotoxicological Evaluation of Simple Xanthone, Cinnamic Acid, and Chalcone Derivatives Using the Microtox Assay for Sustainable Synthetic Design of Biologically Active Molecules. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 12998. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412998