Air Quality Prediction Affected by Different Activation Functions and Hidden Layer Nodes in Artificial Neural Network Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area and Data Analysis

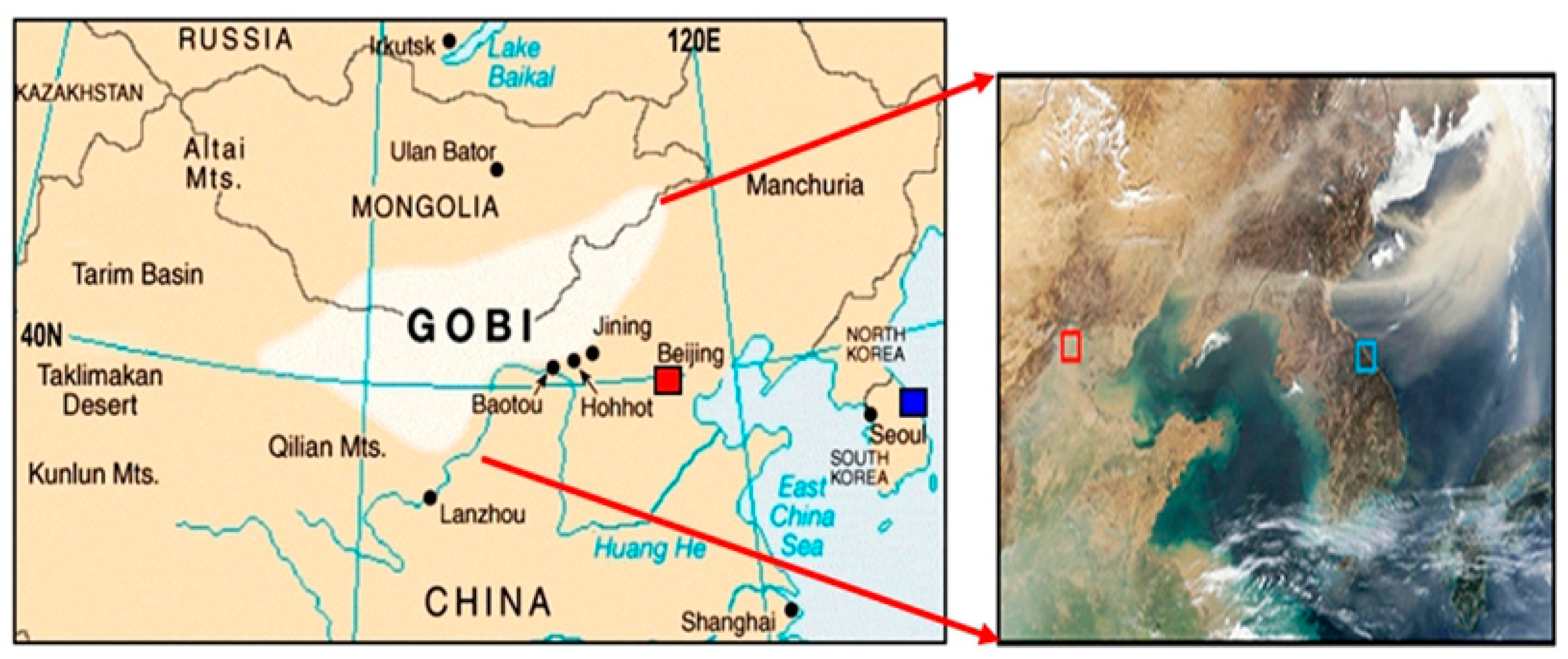

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Data Acquisition and Analysis

3. Artificial Neural Network Models

3.1. Artificial Neural Network Techniques with Sigmoid and Tanh Functions

3.2. Training, Testing, and Validation of PM10, PM2.5, and NO2 by ANN Models

4. Results

4.1. Prediction Performance of ANN Model

4.1.1. Evaluation of Air Quality by ANN Models

4.1.2. Prediction Accuracy of the ANN Models for Training, Testing, and Validation

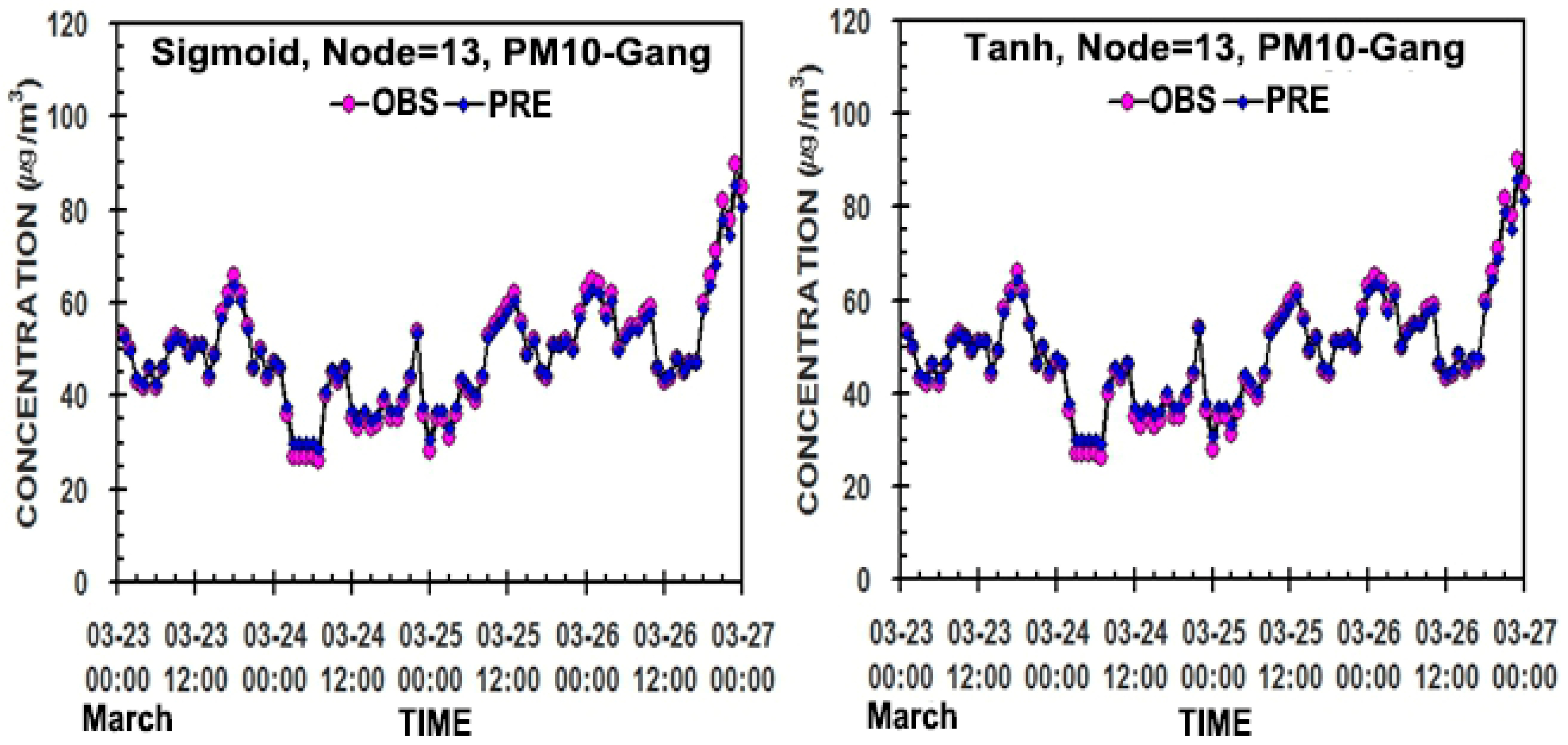

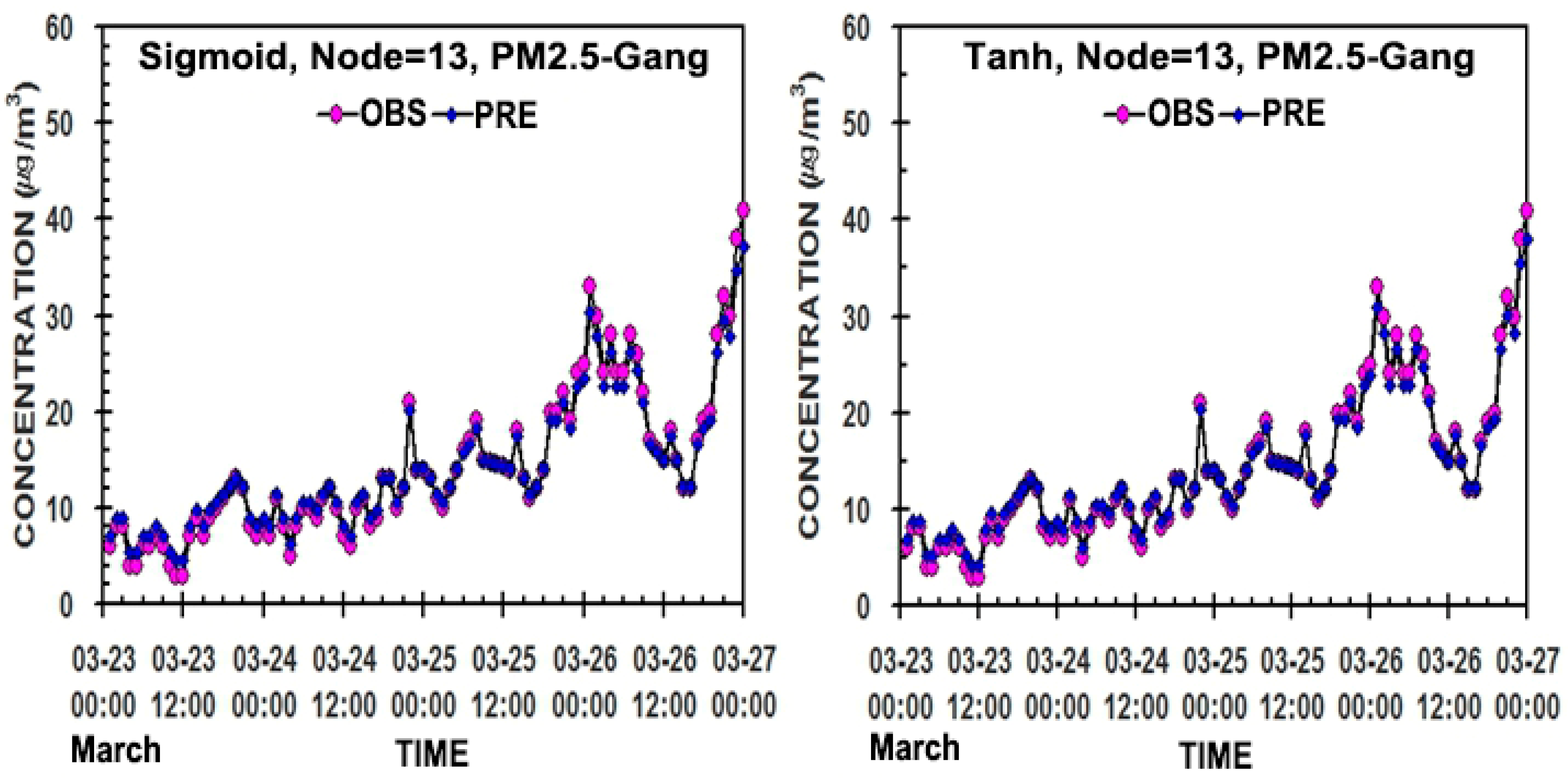

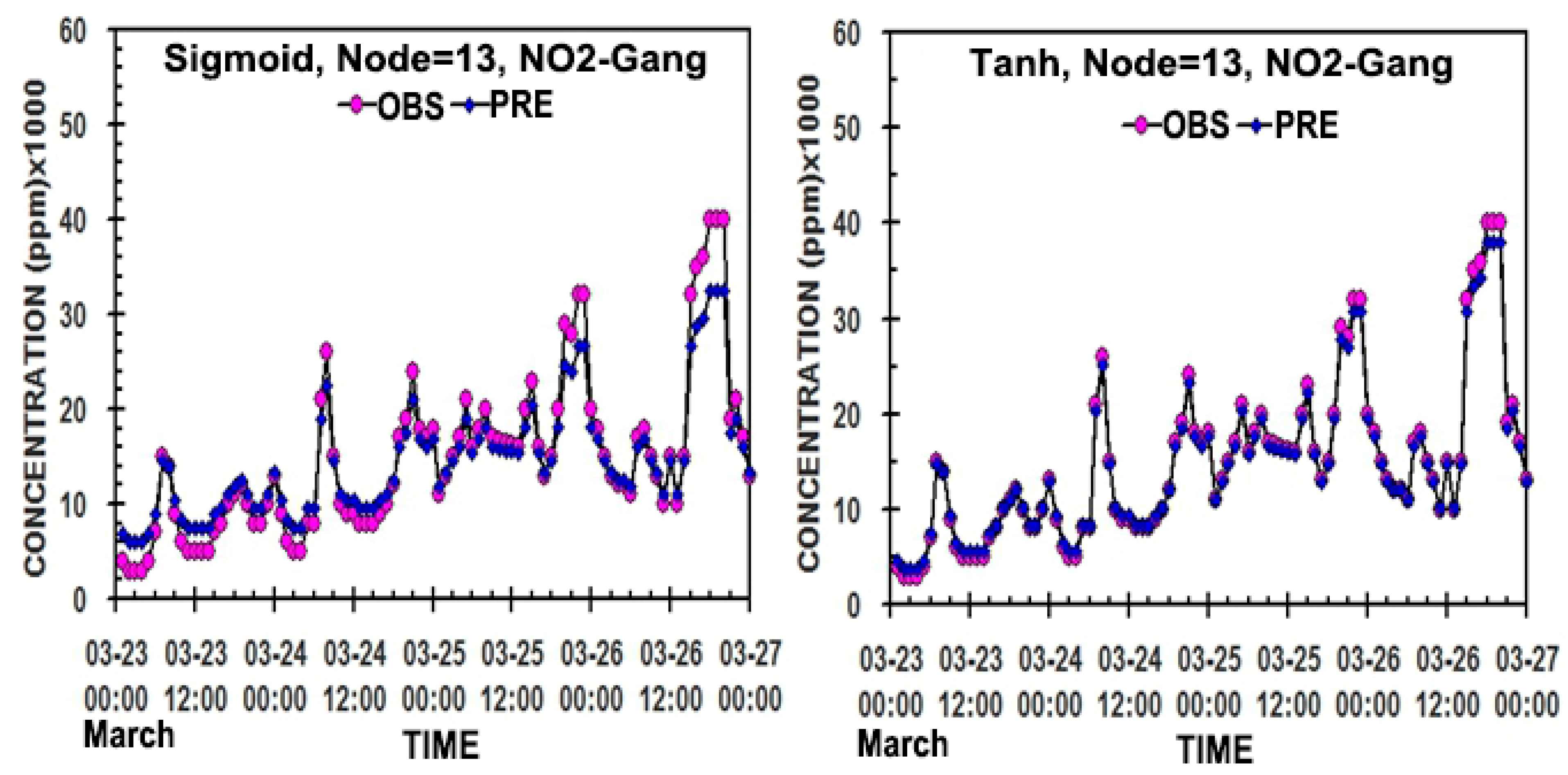

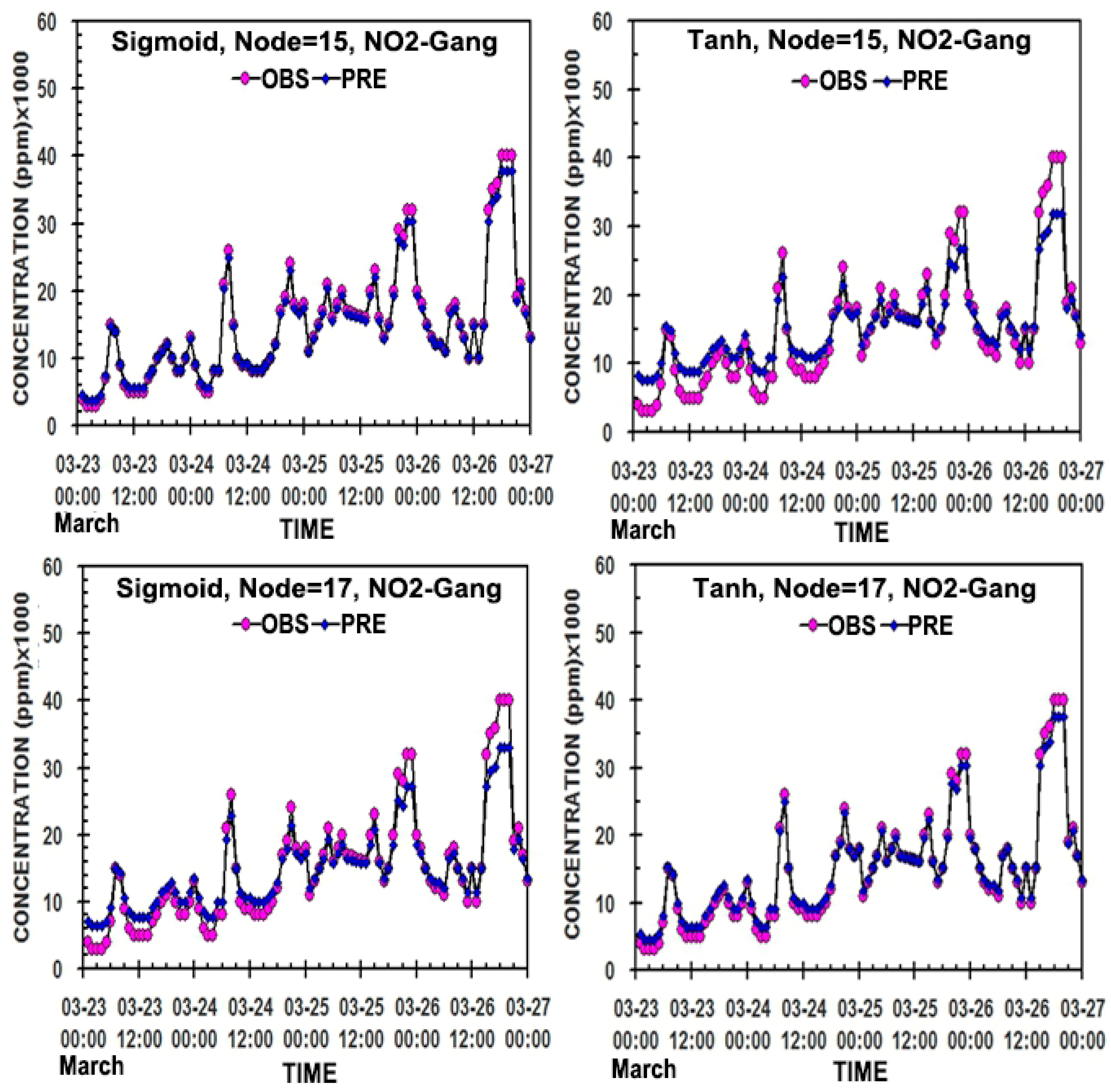

4.2. Comparison of Output Variables Using ANN Models

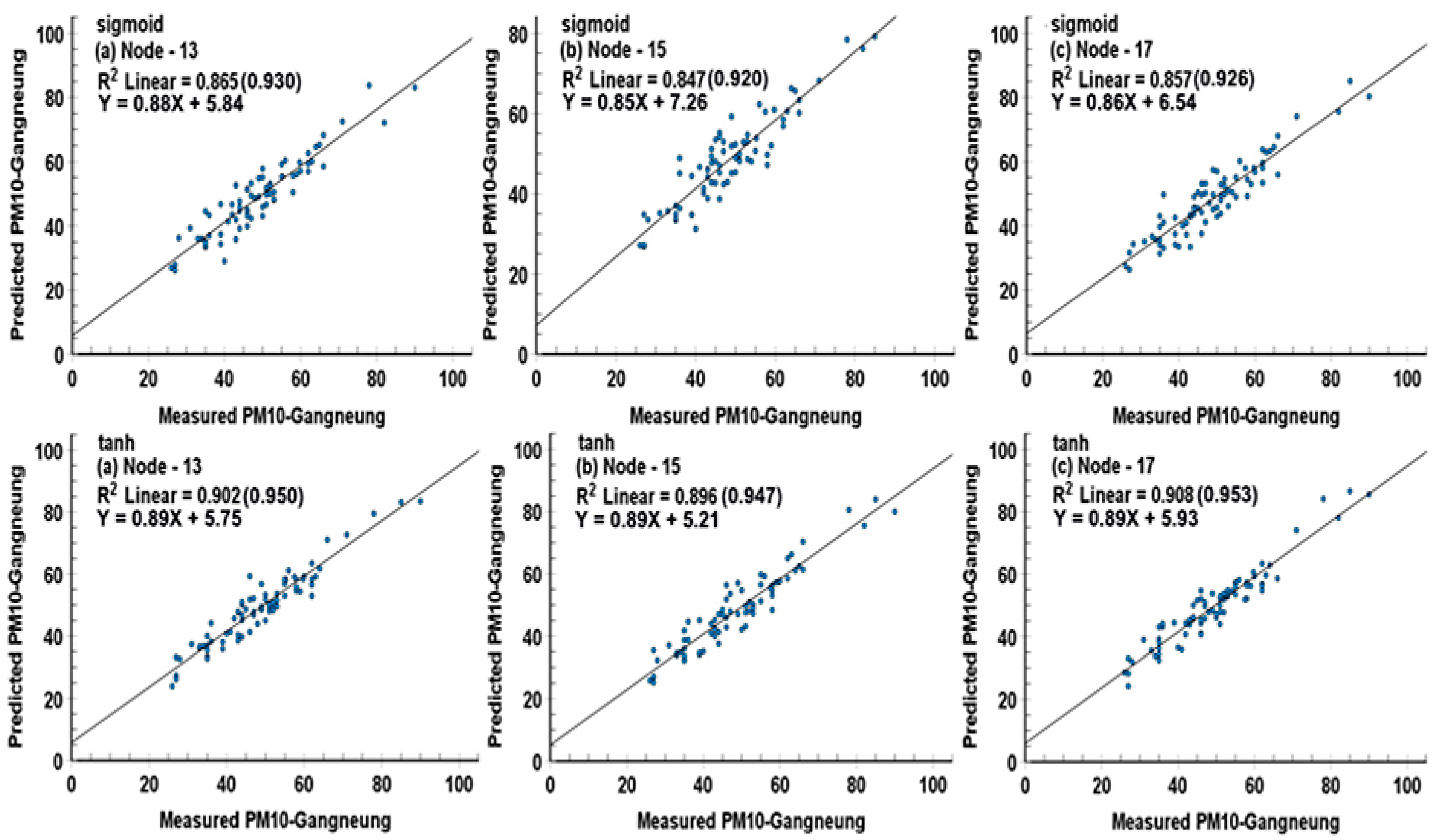

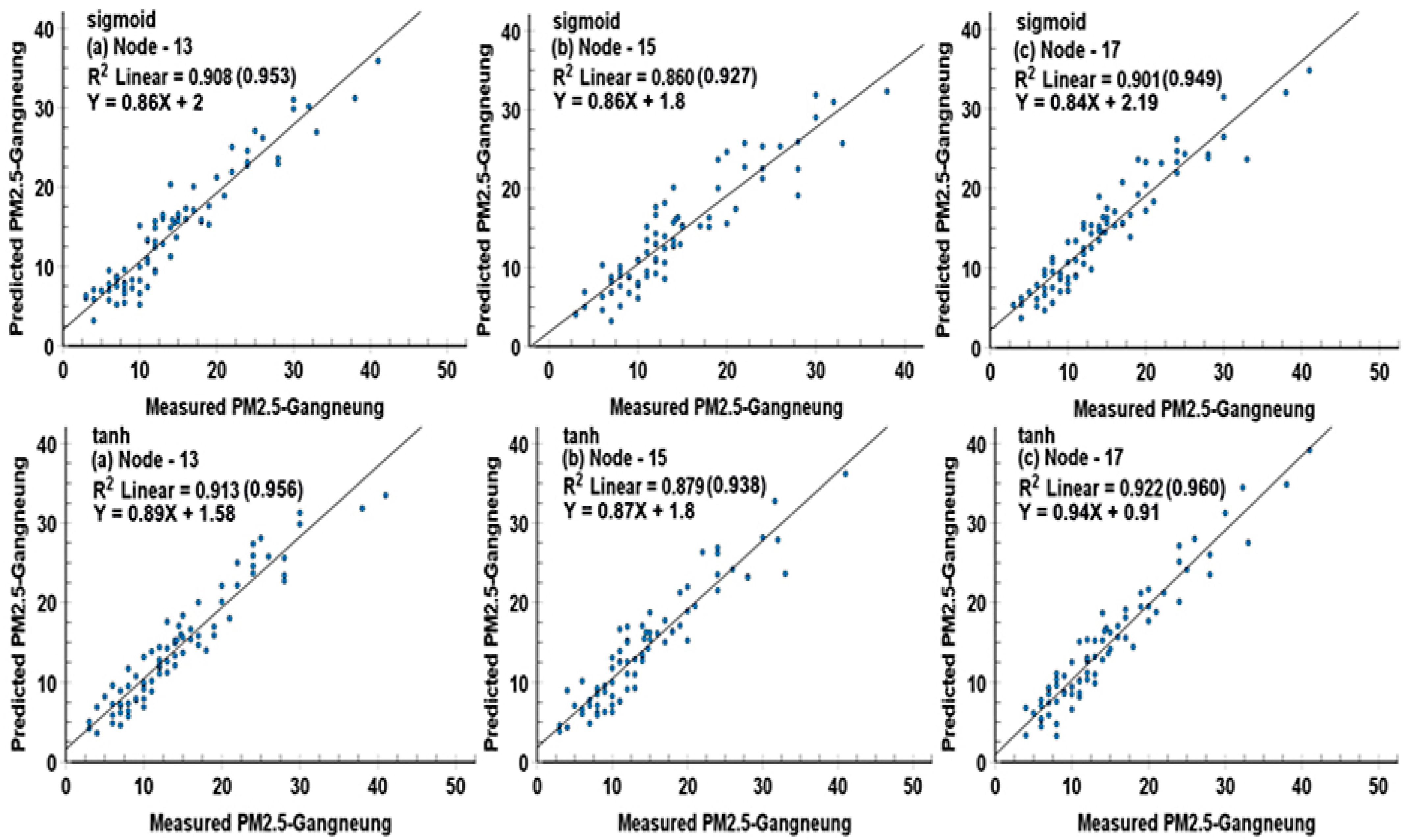

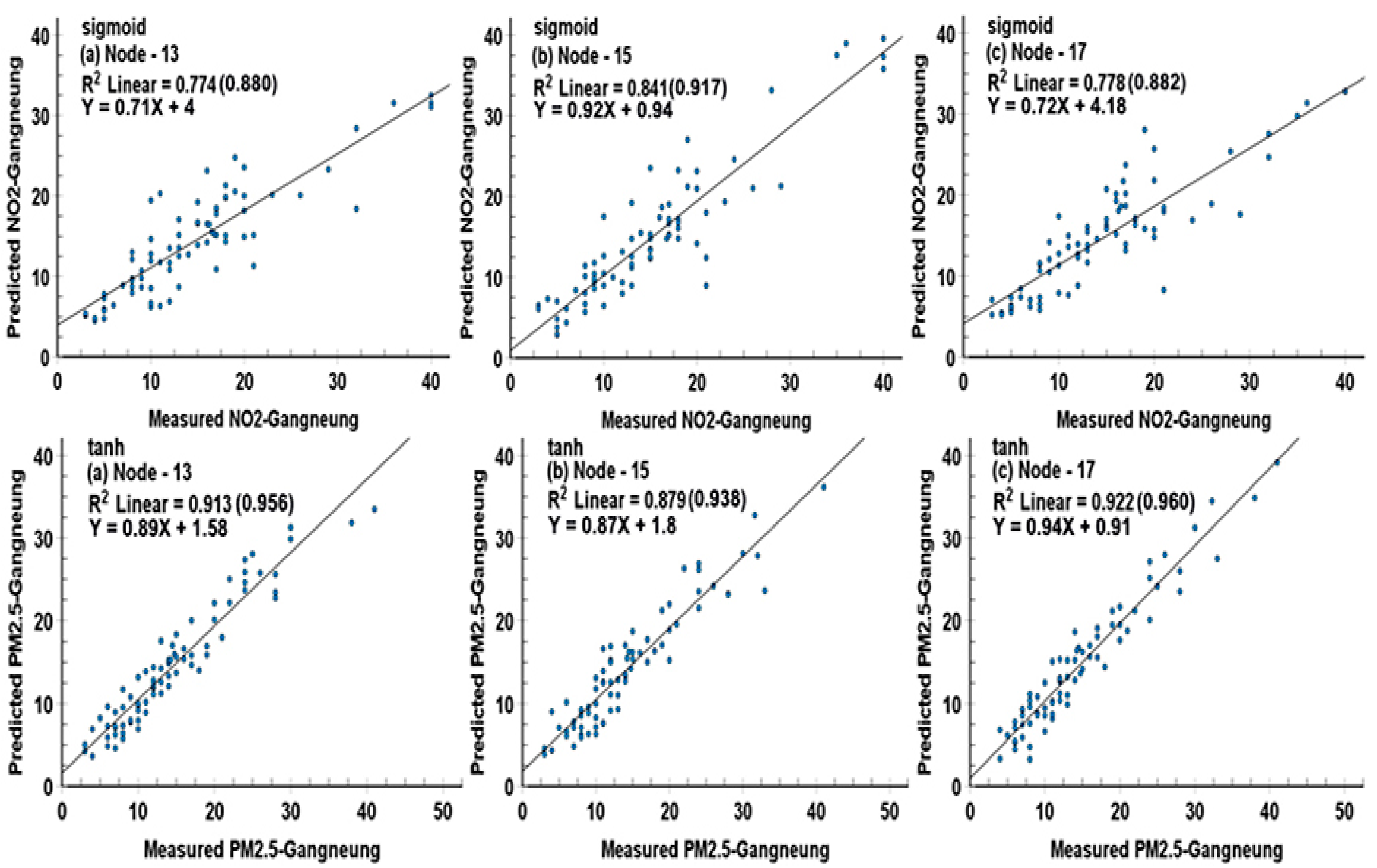

4.2.1. Scatter Plots with Empirical Equations and R2

4.2.2. Sensitivity of the ANN Model Prediction Performance

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The two models’ forecasting abilities between the predicted and measured values show the values of Pearson R by ANN-sig (ANN-tanh) with different 13, 15, or 17 node numbers in the hidden layer than input layer (15 nodes) were 0.930 (0.950), 0.920 (0.947), and 0.926 (0.953) on PM10, 0.953 (0.956), 0.927 (0.938), and 0.949 (0.960) on PM2.5, and 0.880 (0.959), 0.917 (0.886), and 0.882 (0.939) on NO2.

- (2)

- Regardless of different node numbers and activation functions, the predicted values of PM10 and PM2.5 through the two models’ simulations were very close to the measured ones, except for a slight bias of the predicted values in 13 and 17 hidden nodes with the sigmoid function and 15 nodes with the tanh function for NO2.

- (3)

- Overall, the predicted values by the ANN-tanh model reflect the measured ones better than those by the ANN-sigmoid model, and so, it is recommended as an optimal prediction model. However, the ANN-sigmoid model will also be useful because it still has an excellent prediction ability, due to a small discrepancy in the prediction ability as compared with the ANN-tanh model.

- (4)

- More nodes (17 nodes) in its hidden layer than the input layer (15 nodes) produce better prediction results in the two models, as shown in their temporal distributions and scatter plots. Thus, the current study cannot agree with Roy’s instance, such as underfitting in small node numbers in the hidden layer, overfitting in larger node numbers, and bestfitting in the same node numbers in the input layer.

- (5)

- Another importance is that the suggested two models can be used effectively to predict the current urban air quality state of Gangneung city (Republic of Korea), using previous time input variables (air pollutants-PM10, PM2.5, SO2, NO2, CO, and O3; meteorological elements—air temperature, wind speed, and relative humidity) affected by the 48 hours earlier air pollutants of the upwind Beijing city (China).

- (6)

- In a similar way, later air quality forecasting state of Gangneung city at a certain future time (such as 3 h later) can be calculated sequentially, using the current urban air quality and meteorological data sets (Gangneung city), and the 45 hours earlier pollutant data (Beijing city). Practically, the empirical formula derived from the correlation between the predicted and measured values suggested through the two models’ simulation can be well used to predict the air quality state, at the forecasting time, and sequentially at a certain future time.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, S.C.; Cheng, Y.; Ho, K.F.; Cao, J.J.; Loui, P.K.K.; Chow, J.C.; Watson, J.G. PM10 and PM2.5 characteristics in the roadside environment of Hong Kong. Aerosol. Sci. Tech. 2006, 40, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Ha, K. Characteristics of PM10, PM2.5, CO2 and CO monitored in interiors and platforms of subway train in Seoul, Korea. Environ. Int. 2008, 34, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R.; Kucera, V.; Tidblad, J.; Watt, J. The Effect of Air Pollution on Cultural Heritage; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–306. ISBN 978-0-387-84892-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Xu, J.; Zhang, S. Valuing the health risks of particulate air pollution in the Pearl River Delta, China. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 15, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, Y.; Lu, J.J.; Hamer, P. Ambient air pollution in China poses a multi-faceted health threat to outdoor physical activity. J. Epidem. Comm. Health 2015, 69, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.Q.; Yu, X.N.; Zhu, B.; Yuan, L.; Ma, J.; Shen, L.; Zhu, J. Characteristics of Aerosol Extinction and Low Visibility in Haze Weather in Winter of Nanjing, China. Environ. Sci. 2016, 36, 1645–1653. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Dai, Z.; Yang, L.; Ma, Z. Spatiotemporal characteristics of air quality across Weifang from 2014–2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 2019, 16, 3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Han, L.; Wei, H.; Tan, X.; Zhou, W.; Li, W.; Qian, Y. Linking urbanization and air quality together: A review and a persective on the future sustainable urban development. J. Clear Prod. 2022, 346, 130988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, H.; Das, B.K. The Impacts of Air Pollution on Human Health and Well-Being: A Comprehensive Review. J. Environ. Impact Manag. Policy 2023, 36, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Arimoto, R. Atmospheric trace elements over source regions for Chinese dust: Concentrations, sources and atmospheric deposition on the losses plateau. Atmos. Environ. 1993, 27, 2051–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, H. Historical records of yellow sand observations in China. Res. Environ. Sci. 1994, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, G.R.; Hong, M.S.; Ueda, H.; Chen, L.L.; Murano, K.; Park, J.K.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y.; Kang, C.; Shim, S. Aerosol composition at Cheju Island, Korea. J. Geophys. Res. 1997, 102, 6047–6061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.S.; Yoon, M.B. On the occurrence of yellow sand and atmospheric loadings. Atmos. Environ. 1996, 30, 2387–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Chen, H.; Wen, G.; Chen, S.; Tao, Z.; Chung, Y. The relation between sandstorms and strong winds in Xinjiang, China. Water Air Soil Poll. Focuss 2003, 3, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Zhang, Y.H. Predicting duststorm evolution with vorticity theory. Atmos. Res. 2008, 89, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Choi, D.S.; Choi, S.-M. Meteorological condition and atmospheric boundary layer influenced upon temporal concentrations of PM1, PM2.5 at a Coastal City, Korea for Yellow Sand Event from Gobi Desert. Disaster Adv. 2010, 3, 309–315. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.-M.; Choi, H.; Paik, W. Multivariate regression modeliing for coastal urban air quality estimate. Appl. Sci. 2023, 12, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotamarthi, V.R.; Carmichael, G.R. The long range transport of pollutants in the Pacific Rim region. Atmos. Environ.-A 1990, 24, 1521–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M.T.; Robert, J.F.; Douglas, L.W. April 1998 Asian dust event: A southern California perspective. J. Geophys. Res. 2001, 106, 18371–18379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.H. Long-range transport of yellow sand to Taiwan in spring 2000: Observed evidence and simulation. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 5873–5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendry, I.G.; Hacker, J.P.; Stull, R.; Sakiyama, S.; Mignacca, D.; Reid, K. Long-range transport of Asian dust to the lower Fraser Valley, British Columbia, Canada. J. Geophys. Res. 2001, 106, 18361–18370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uno, I.; Amano, H.; Emori, S.; Kinoshita, K.; Matsui, I.; Sugimoto, N. Tans-Pacific yellow sand transport observed in April, 1998: A numerical simulation. J. Geophys. Res. 2001, 106, 18331–18344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, U.; Kim, J.; Lee, H.; Lee, Y.G. Assessing the effect of long-range pollutant transportion on air quality in Seoul using the conditional potential source contribution function method. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 150, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.S.; Babu, S.R.; Wang, S.-H.; Griffith, S.M.; Chang, J.H.-W.; Chung, M.-T.; Sheu, G.-R.; Lin, N.-H. Expanding the simulation of east Asian super dust storms: Physical transport mechanisms impacting the western Pacific. Atmos. Chem. 2024, 24, 1041–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, N.; Hong, Y. Temporal and spatial analyses of particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5) and its relationship with meteorological parameters over an urban city in northeast China. Atmos. Res. 2017, 198, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J. The effects of transboundary air pollution from China on ambient air quality in South Korea. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-M.; Choi, H. Statistical modeling for PM10, PM2.5, and PM1 at Gangneung affected by local meteorological variables and PM10 and PM2.5 at Beijing for non- and dust periods. App. Sci. 2021, 11, 11958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, T. Practical Neural Network Recipes in C++; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Shahin, M.A.; Jaksa, M.B.; Maier, H.R. Artificial neural network based settlement prediction formula for shallow foundations on granular soils. Aust. Geomech. J. 2002, 36, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, J.; Chen, L.; Sun, Y.; Mao, J.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Z.; Yang, W.; et al. Soil-derived dust PM10 and PM2.5 fractions in Southern Xinjiang, China, using an artificial neural network model. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawras, S.; Hani, A.-Q. Assessing and predicting air quality in northern Jordan during the lockdown due to the COVID-19 virus pandemic using artificial neural network. Air. Qual. Atmos. Health 2021, 14, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-M.; Choi, H. Artificial neural network modeling on PM10, PM2.5 and NO2 concentrations between two megacities without a lockdown in Korea, for the COVID-19 pandemic period of 2022. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Son, Y.S. Prediction of fine dust PM10 using a deep neural network model. Korean J. Appl. Stat. 2018, 31, 205–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Lee, S. Hourly prediction of particulate matter (PM2.5) concentration using time series data and random forest. KIPS Trans. Softw. Data Eng. 2020, 9, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-M. Improved air quality forecasting based on machine learning and multivariate regression techniques. Informatica 2024, 35, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.S. Forecasting the air temperature at a weather station using deep neural networks. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 178, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R. Learning representations by back-propagation error. Nature 1996, 323, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, S.; Gautam, Y.; Bhattaral, A. Evaluation of temperature based empirical model and machine learning technique to estimate daily global solar radiation at Biratnagar airport, Nepal. Adv. Meteorol. 2020, 11, 8895311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiwal, S. Multilayer Percetrons in Machine Learning: A Comprehensive Guide. Available online: https://www.datacamp.com/tutorial/multilayer-perceptrons-in-machine-learning (accessed on 29 July 2024).

| Input Variable | Definition of Abbreviation | Output Variable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM10-G | Particulate Matter < 10 um (μg/m3) | 3 h before | (31) PM10-G(F) (32) PM2.5-G(F) (33) NO2-G(F) at the forecasting time of Gangneung city | |

| PM2.5-G | Particulate Matter < 2.5 um (μg/m3) | |||

| T-G | Air Temperature (°C) | |||

| W-G | Wind Speed (m/s) | |||

| RH-G | Relative Humidity (%) | |||

| SO2-G | Sulfur Dioxide (ppm) | |||

| CO-G | Carbon Monoxide (ppm) | |||

| NO2-G | Nitrogen Dioxide (ppm) | |||

| O3-G | Ozone (ppm) | |||

| PM10-B | Particulate Matter < 10 um (μg/m3) | 48 h before | ||

| PM2.5-B | Particulate Matter < 2.5 um(μg/m3) | |||

| SO2-B | Sulfur Dioxide (ppm) | |||

| CO-B | Carbon Monoxide (ppm) | |||

| NO2-B | Nitrogen Dioxide (ppm) | |||

| O3-B | Ozone (ppm) | |||

| Sigmoid/(Tanh)Function | |||||||

| Item | Hidden Neuron No. | RMSE | R2 | ||||

| Training | Testing | Validation | Training | Testing | Validation (Pearson R) | ||

| PM10 | 13 | 0.4672 (0.1500) | 2.4997 (2.0124) | 1.4992 (1.4293) | 0.972 (0.987) | 0.826 (0.848) | 0.865 (0.930) (0.902 (0.950)) |

| 15 | 0.2537 (0.3798) | 2.4095 (1.2572) | 1.8746 (1.3822) | 0.971 (0.986) | 0.812 (0.887) | 0.847 (0.920) (0.896 (0.947)) | |

| 17 | 0.5345 (0.2503) | 2.6367 (3.2483) | 1.7711 (1.4888) | 0.970 (0.989) | 0.832 (0.822) | 0.857 (0.926) (0.908 (0.953)) | |

| PM2.5 | 13 | 0.3218 (0.2365) | 0.9767 (1.0474) | 1.1037 (0.8671) | 0.968 (0.974) | 0.897 (0.878) | 0.908 (0.953) (0.913 (0.956)) |

| 15 | 0.2533 (0.1939) | 0.9465 (0.6270) | 1.1235 (1.0269) | 0.969 (0.981) | 0.897 (0.885) | 0.860 (0.927) (0.879 (0.938)) | |

| 17 | 0.3200 (0.2367) | 0.8818 (1.2672) | 1.2658 (0.4754) | 0.970 (0.987) | 0.878 (0.826) | 0.901 (0.949) (0.922 (0.960)) | |

| NO2 | 13 | 0.4280 (0.1163) | 1.8198 (0.8637) | 2.4895 (0.6207) | 0.967 (0.986) | 0.791 (0.907) | 0.774 (0.880) (0.920 (0.959)) |

| 15 | 0.3504 (0.0991) | 0.9897 (1.3072) | 0.7266 (2.9292) | 0.958 (0.990) | 0.874 (0.805) | 0.841 (0.917) (0.785 (0.886)) | |

| 17 | 0.5974 (0.2683) | 2.1768 (1.0448) | 2.3828 (0.9613) | 0.945 (0.982) | 0.785 (0.880) | 0.778 (0.882) (0.882 (0.939)) | |

| Pearson R | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Model | (Hourly) Before YD | (Hourly) During YD | (Hourly) After YD | (Hourly)-Non YD (Daily) | |||||||||||

| PM10 | PM2.5 | NO2 | PM10 | PM2.5 | NO2 | PM10 | PM2.5 | NO2 | PM10 | PM2.5 | NO2 | PM10 | PM2.5 | NO2 | ||

| Jeon and Son (2018) [33] | SVM | 0.751 | ||||||||||||||

| RF | 0.726 | |||||||||||||||

| ANN-sig | 0.737 | |||||||||||||||

| Kim (2019) [26] | Multivariate | 0.849 | ||||||||||||||

| Lee and Lee (2020) [34] | ANN-sig | 0.837 | ||||||||||||||

| LSTM | 0.907 | |||||||||||||||

| RF | 0.910 | |||||||||||||||

| Choi, et al. (2023) [17] | Multivariate | 0.957 | 0.906 | 0.886 | 0.936 | 0.982 | 0.866 | 0.919 | 0.945 | 0.902 | ||||||

| Choi (2024) [35] | ANN-tanh | 0.935 | 0.942 | 0925 | 0.943 | 0.969 | 0.853 | 0.947 | 0.938 | 0886 | ||||||

| Multivariate | 0.961 | 0.909 | 0.896 | 0.948 | 0.977 | 0.875 | 0.920 | 0.947 | 0.903 | |||||||

| Choi (present) | ANN-sig | 0.930 | 0.953 | 0.917 | ||||||||||||

| ANN-tanh | 0.953 | 0.960 | 0.959 | |||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, S.-M. Air Quality Prediction Affected by Different Activation Functions and Hidden Layer Nodes in Artificial Neural Network Models. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12863. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412863

Choi S-M. Air Quality Prediction Affected by Different Activation Functions and Hidden Layer Nodes in Artificial Neural Network Models. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):12863. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412863

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Soo-Min. 2025. "Air Quality Prediction Affected by Different Activation Functions and Hidden Layer Nodes in Artificial Neural Network Models" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 12863. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412863

APA StyleChoi, S.-M. (2025). Air Quality Prediction Affected by Different Activation Functions and Hidden Layer Nodes in Artificial Neural Network Models. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 12863. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412863