Analyzing the Contribution of Bare Soil Surfaces to Resuspended Particulate Matter in Urban Areas via Machine Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In Situ Observational Data

- Population and activities distribution within inverse-distance weighted interpolation of 500 m, combining data from the Population and Housing Census in the Republic of Bulgaria, as well as Points Of Interest (POI) from a functional analysis performed and additionally weighted by functional types, both provided by Sofiaplan municipal enterprise and described in [50]. In particular, we exploit the ‘actuse’ feature, which corresponds to the estimated density of active users of motorized vehicles in a given area. It is related to both traffic-based PM10 concentration and the formation of muddy patches.

- Number of households having solid-fuel heating (wood, coal and other related heating sources) within the inverse-distance weighted interpolation of 500 m. The data derive from the Population and Housing Census in the Republic of Bulgaria and were provided at the neighborhood level using small-scale urban polygons () by the National Statistics Institute in 2024 under the ‘Strategic research and innovation program for the development of MU Plovdiv’ (SRIPD-MUP project), described in [51].

- Modeled traffic on the basis of various data sources, described in [52].

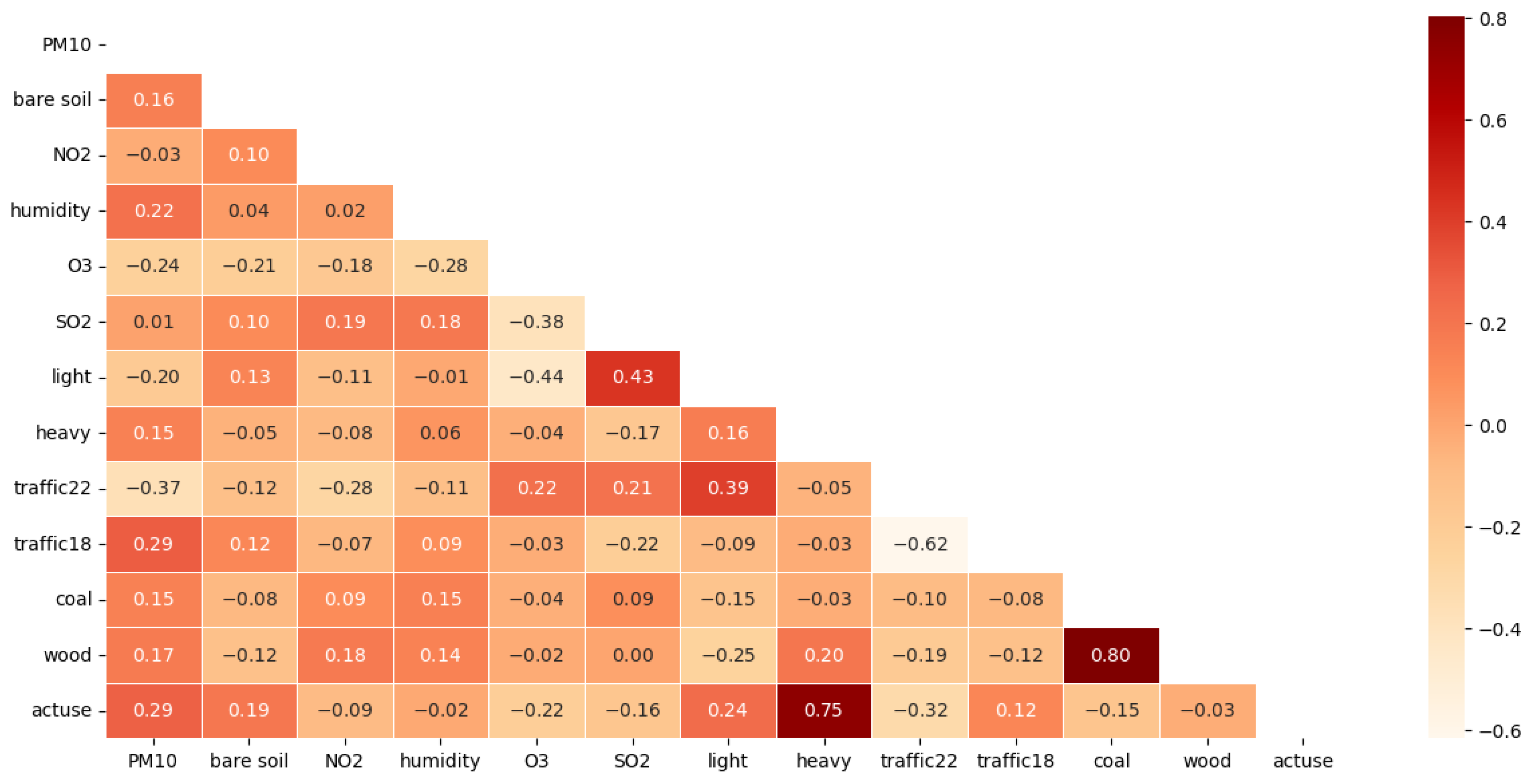

2.2. Factor Analysis

2.3. Processing of Spectral Indices for Identification of Mud Patches in Sofia Municipality

- The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) serves to quantitatively assess the density and health of the vegetation cover. In this study, it is used to exclude areas with dense vegetation from the analysis, since such areas do not represent a source of mud or dust pollution.

- The Normalized Difference Moisture Index (NDMI) is used to assess the moisture content of soil and vegetation. Mud patches are usually characterized by increased moisture, making this index particularly suitable for their detection. NDMI facilitates the distinction between moist soil and dry, bare surfaces or paved surfaces such as asphalt.

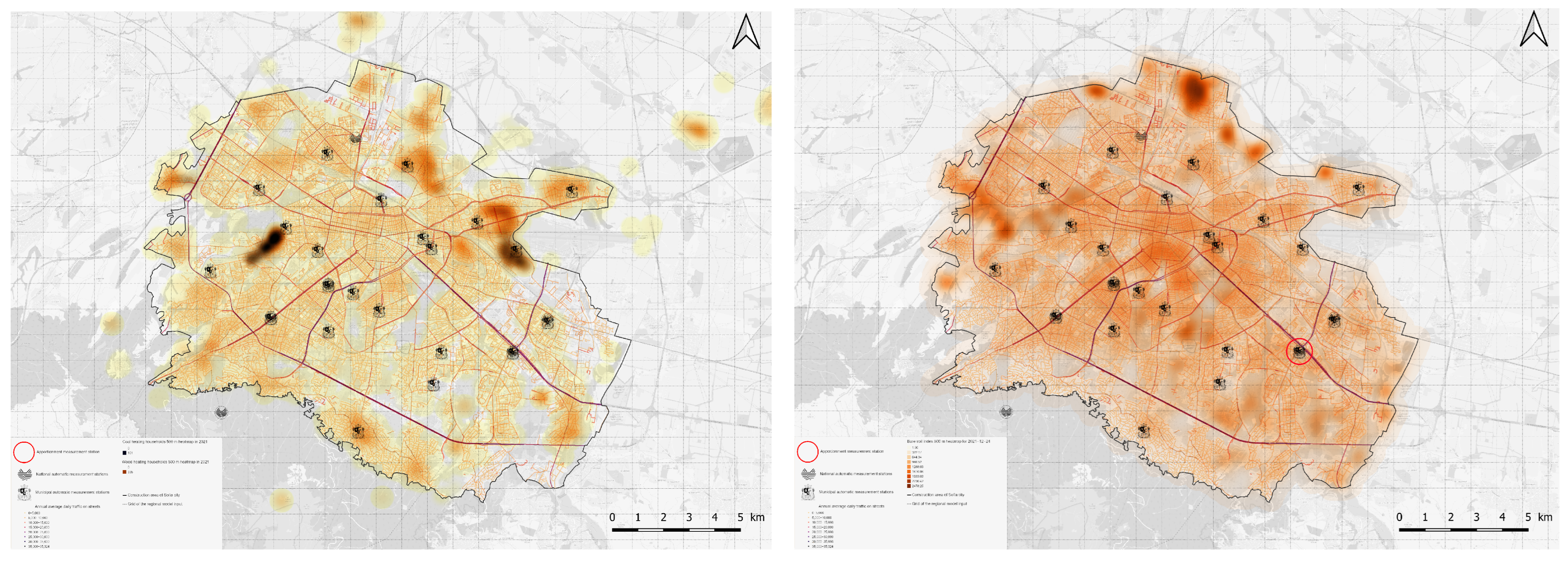

- The Bare Soil Index (BSI) also aims at detecting bare soil areas, but it uses additional spectral information from the blue and red ranges, which improves the accuracy of detecting bare and potentially dusty surfaces in urban environments (see Figure 1).

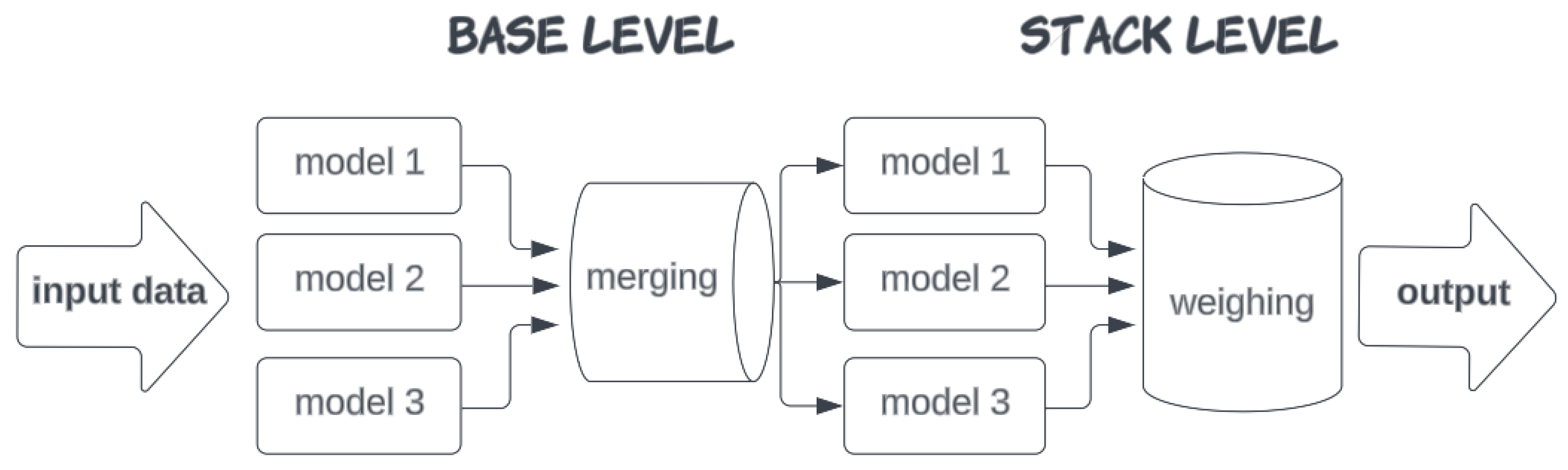

2.4. Statistics and Machine Learning

3. Results

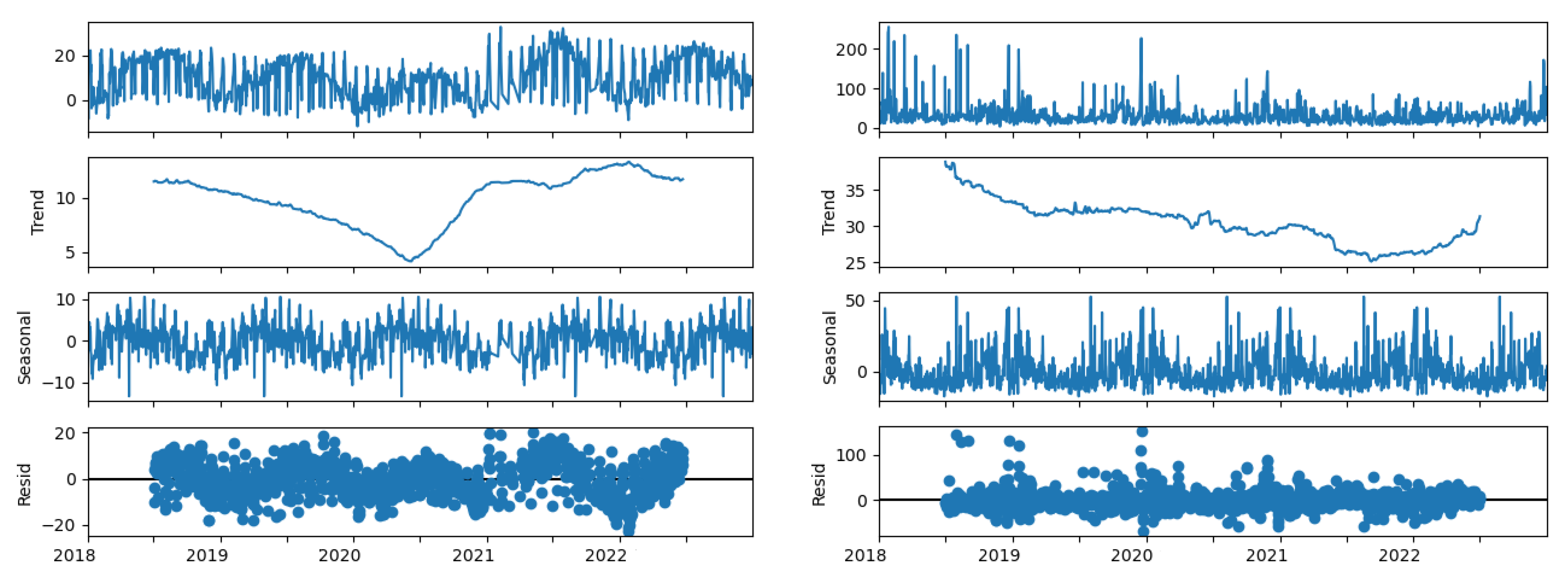

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Time Series Analysis

3.2. Data Pre-Processing

3.3. Synthetic Data Generation

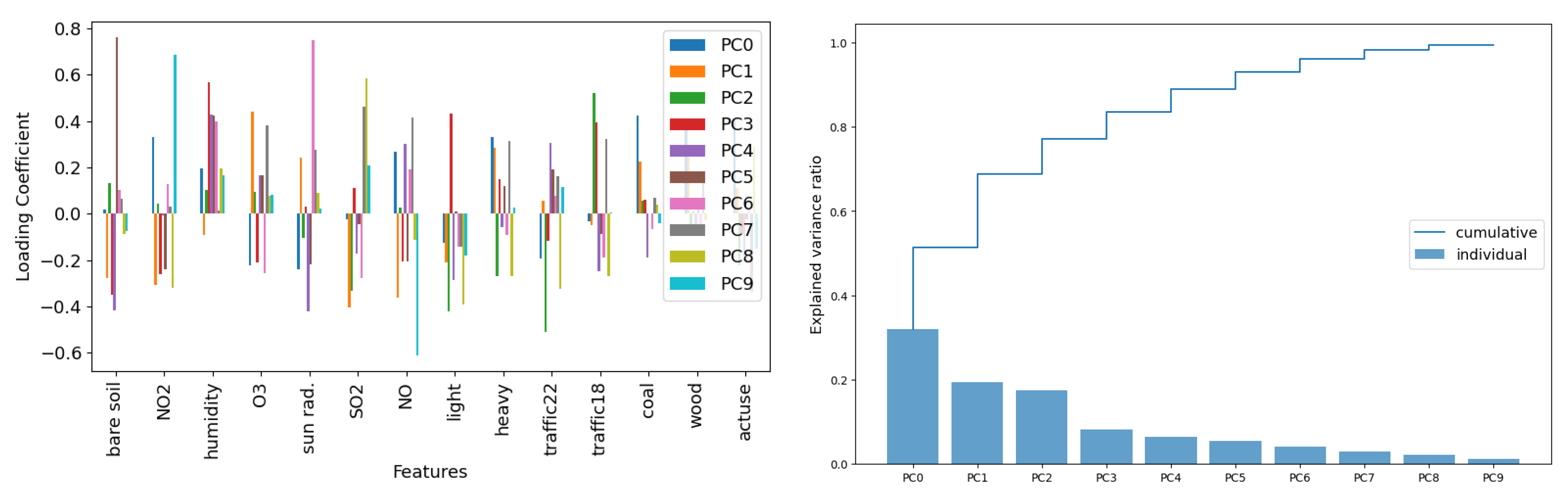

3.4. Principal Component Analysis

3.5. Machine Learning Modeling

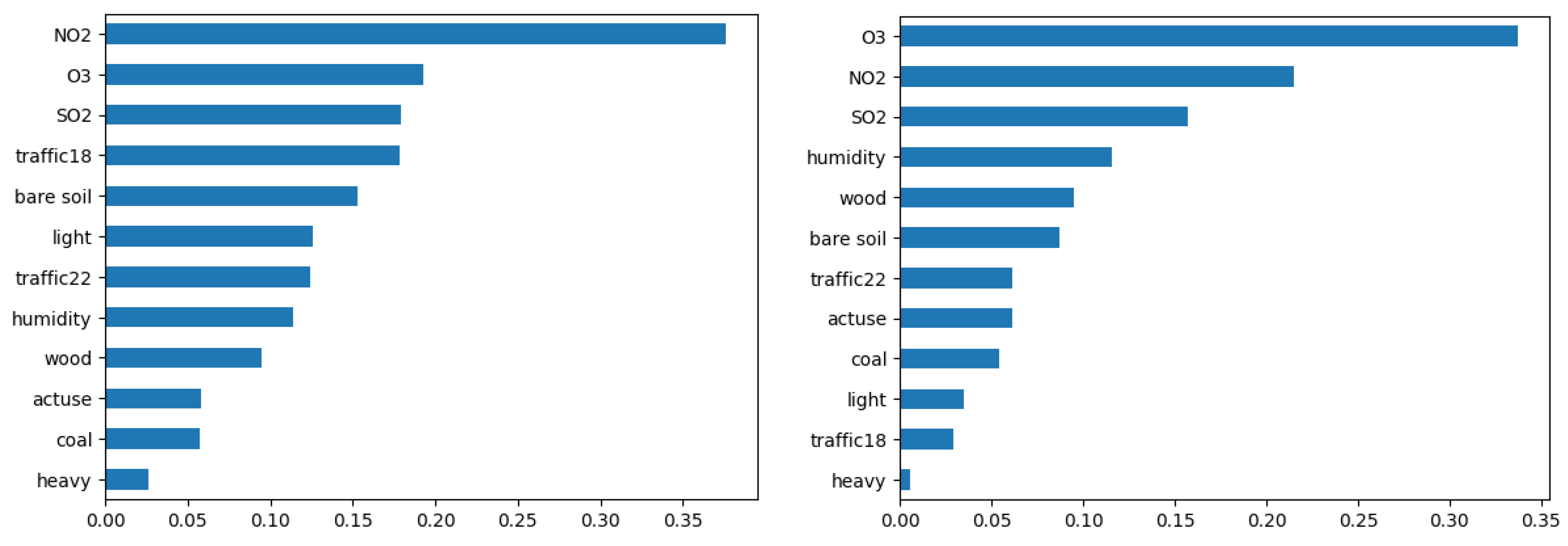

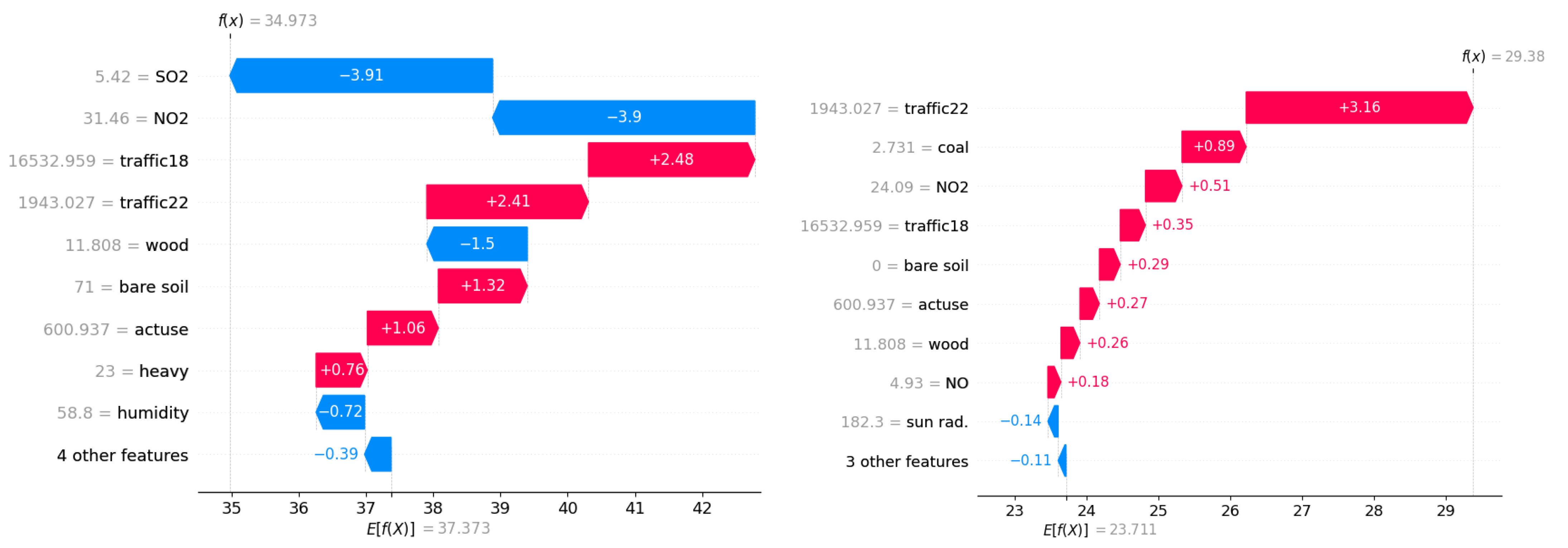

3.6. Feature Importance Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NDMI | Normalized Difference Moisture Index |

| BSI | Bare Soil Index |

| PM | particulate matter |

| POI | Points Of Interest |

| AQS | air quality station |

| SA | source appointment |

| PMF | positive matrix factorization |

| KNN | k nearest neighbors (imputation) |

| MICE | multiple imputation by chained equations |

| GCS | Gaussian Copula Synthesizer |

| SMOTER | synthetic minority oversampling technique for regression |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

| XGBoost | extreme gradient boosting |

| WE_L2/L3 | level two/three weighted ensemble meta-models |

References

- Romero-Lankao, P.; Dodman, D. Cities in Transition: Transforming Urban Centres from Hotbeds of GHG Emissions and Vulnerability to Seedbeds of Sustainability and Resilience: Introduction and Editorial Overview. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 3, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Air Pollution. In Compendium of WHO and Other UN Guidance on Health and Environment; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.urbanagendaplatform.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/WHO-HEP-ECH-EHD-22.01-eng.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Oke, T.R.; Mills, G.; Christen, A.; Voogt, J.A. Urban Climates; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonati, G.; Crippa, M.; Gianelle, V.; Van Dingenen, R. Daily patterns of the multimodal structure of the particle number size distribution in Milan, Italy. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 243–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. Air Quality in Europe—2019 Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019; Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2019 (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Petit, J.E.; Pallarés, C.; Favez, O.; Alleman, L.Y.; Bonnaire, N.; Rivière, E. Sources and geographical origins of PM10 in Metz (France) using oxalate as a marker of secondary organic aerosols by positive matrix factorization analysis. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pio, C.; Alves, C.; Nunes, T.; Cerqueira, M.; Lucarelli, F.; Nava, S.; Calzolai, G.; Gianelle, V.; Colombi, C.; Amato, F.; et al. Source apportionment of PM2.5 and PM10 by Ionic and Mass Balance (IMB) in a traffic-influenced urban atmosphere, in Portugal. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 223, 117217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, A.; Harrison, R.M. Sources and properties of non-exhaust particulate matter from road traffic: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 400, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttikunda, S.K.; Calori, G. A GIS based emissions inventory at 1 km × 1 km spatial resolution for air pollution analysis in Delhi, India. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 67, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, P.; Drewnick, F.; Borrmann, S. Aerosol particle and trace gas emissions from earthworks, road construction, and asphalt paving in Germany: Emission factors and influence on local air quality. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 122, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Li, Q.; Feng, K.; Zhang, L. The characteristics of PM emissions from construction sites during the earthwork and foundation stages: An empirical study evidence. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 62716–62732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, A.; Polo-Rehn, L.; Besombes, J.-L.; Golly, B.; Buisson, C.; Chanut, H.; Marchand, N.; Guillaud, G.; Jaffrezo, J.-L. Identification and quantification of particulate tracers of exhaust and non-exhaust vehicle emissions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 5187–5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Srivastava, R.K.; Bhatt, A.K. Major Air Pollutants. In Battling Air and Water Pollution; Springer: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupiainen, K.K.; Tervahattu, H.; Räisänen, M.; Mäkelä, T.; Aurela, M.; Hillamo, R. Size and composition of airborne particles from pavement wear, tires, and tractor sanding. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, M.; Johansson, C. Studies of some measures to reduce road dust emissions from paved roads in Scandinavia. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 6154–6164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casotti Rienda, I.; Alves, C.A. Road dust resuspension: A review. Atmos. Res. 2021, 261, 105740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denby, B.R.; Kupiainen, K.J.; Gustafsson, M. Chapter 9—Review of Road Dust Emissions. In Non-Exhaust Emissions; Amato, F., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, F.; Pandolfi, M.; Viana, M.; Querol, X.; Alastuey, A.; Moreno, T. Spatial and chemical patterns of PM10 in road dust deposited in urban environments. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 1650–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarmoshenko, I.; Malinovsky, G.; Baglaeva, E.; Seleznev, A. A Landscape Study of Sediment Formation and Transport in the Urban Environment. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, D.; Zhao, C.; Kwan, M.; Cai, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Wang, X.; Chen, B.; Yang, J.; et al. Influence of Meteorological Conditions on PM2.5 Concentrations Across China: A Review of Methodology and Mechanism. Environ. Int. 2020, 139, 105558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talepour, N.; Birgani, Y.T.; Kelly, F.J.; Jaafarzadeh, N.; Goudarzi, G. Analyzing Meteorological Factors for Forecasting PM10 and PM2.5 Levels: A Comparison between MLR and MLP Models. Earth Sci. Inform. 2024, 17, 5603–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Jiao, J.; Pan, C.; Wang, G.; Li, C.; Jia, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, G. The Impact of Meteorological Factors and Canopy Structure on PM2.5 Dynamics Under Different Urban Functional Zones in a Subtropical City. Forests 2025, 16, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Lin, Z.; Yang, L.; Jiang, M.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, S.; Gu, Y.; Ye, W.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. A Study on the Impact of Meteorological and Emission Factors on PM2.5 Concentrations Based on Machine Learning. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Wang, M.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Jin, X.; Ren, Y.; Chen, J. Historical Pollution Exposure Impacts on PM2.5 Dry Deposition and Physiological Responses in Urban Trees. Forests 2024, 15, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Song, J.; Sun, H. Temporal and Spatial Trends in Particulate Matter and the Responses to Meteorological Conditions and Environmental Management in Xi’an, China. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.; Welker, A.; Helmreich, B. Critical Review of Heavy Metal Pollution of Traffic Area Runoff: Occurrence, Influencing Factors, and Partitioning. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 541, 895–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezonik, P.L.; Stadelmann, T.H. Analysis and Predictive Models of Stormwater Runoff Volumes, Loads, and Pollutant Concentrations from Watersheds in the Twin Cities Metropolitan Area, Minnesota, USA. Water Res. 2002, 36, 1743–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Xu, Y.; Yan, B.; Guan, J. Snowmelt Runoff: A New Focus of Urban Nonpoint Source Pollution. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 4333–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, C.; Viklander, M. Particles and Associated Metals in Road Runoff During Snowmelt and Rainfall. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 362, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilliges, R.; Endres, M.; Tiffert, A.; Brenner, E.; Marks, T. Characterization of Road Runoff with Regard to Seasonal Variations, Particle Size Distribution and the Correlation of Fine Particles and Pollutants. Water Sci. Technol. 2017, 75, 1169–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furberg, A.; Arvidsson, R.; Molander, S. Dissipation of Tungsten and Environmental Release of Nanoparticles from Tire Studs: A Swedish Case Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Dzakpasu, M.; Chang, N.; Wang, X. Transferral of HMs Pollution from Road-Deposited Sediments to Stormwater Runoff During Transport Processes. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2019, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, S.J.; Dang, C.; Hegg, D.A.; Zhang, R.; Warren, S.G. Black Carbon and Other Light-Absorbing Particles in Snow of Central North America. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2014, 119, 12807–12831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarenko, Y.; Fournier, S.; Kurien, U.; Rangel-Alvarado, R.B.; Nepotchatykh, O.; Seers, P.; Ariya, P.A. Role of Snow in the Fate of Gaseous and Particulate Exhaust Pollutants from Gasoline-Powered Vehicles. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 223, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA, Health and Environmental Effects of Particulate Matter (PM). Available online: https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/health-and-environmental-effects-particulate-matter-pm (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Orellano, P.; Kasdagli, M.-I.; Pérez Velasco, R.; Samoli, E. Long-Term Exposure to Particulate Matter and Mortality: An Update of the WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Public Health 2024, 69, 1607683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Effects Institute. State of Global Air 2024, a Special Report on Global Exposure to Air Pollution and Its Health Impacts, with a Focus on Children’s Health; Health Effects Institute; Boston, MA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.stateofglobalair.org/resources/archived/state-global-air-report-2024 (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Weinmayr, G.; Romeo, E.; De Sario, M.; Weiland, S.K.; Forastiere, F. Short-term effects of PM10 and NO2 on respiratory health among children with asthma or asthma-like symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, R.; Lurponglukana, N.; Fernando, H.J.S.; Runger, G.C.; Hyde, P.; Hedquist, B.C.; Anderson, J.; Bannister, W.; Johnson, W. Relationship between particulate matter and childhood asthma–basis of a future warning system for central Phoenix. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 2479–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.A., 3rd; Burnett, R.T.; Thun, M.J.; Calle, E.E.; Krewski, D.; Ito, K.; Thurston, G.D. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2002, 287, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, B.K.; Acharya, B.K.; Cao, C.; Xu, M.; Bhattarai, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S. A systematic review of spatial and temporal epidemiological approaches, focus on lung cancer risk associated with particulate matter. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks 2023 Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2023. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 86, 2167–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douwes, J.; Thorne, P.; Pearce, N.; Heederik, D. Bioaerosol health effects and exposure assessment: Progress and prospects. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2003, 47, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, C.M.; Metwali, N.; Baker, Z.; Jayarathne, T.; Kostle, P.A.; Thorne, P.S.; O’Shaughnessy, P.T.; Stone, E.A. Urban enhancement of PM10 bioaerosol tracers relative to background locations in the Midwestern United States. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2016, 121, 5071–5089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.; Seo, J.H.; Kim, Y.-K.; Yang, J. Examining the bacterial diversity including extracellular vesicles in air and soil: Implications for human health. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hristova, E.; Veleva, B.; Georgieva, E.; Branzov, H. Application of Positive Matrix Factorization Receptor Model for Source Identification of PM10 in the City of Sofia, Bulgaria. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, B.; Tansey, K.; Whelan, M. Satellite Remote Sensing Techniques and Limitations for Identifying Bare Soil. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Executive Environment Agency (EEA). System for Informing the Population About the Quality of Atmospheric Air. Available online: https://eea.government.bg/kav (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Executive Environment Agency (EEA). National Report for the Condition and Preservation of the Environment: Pollutant Emissions and Quality of the Atmospheric Air. 2023. Available online: https://eea.government.bg/bg/soer/2024/1Air.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2025). (In Bulgarian)

- Burov, A.; Brezov, D. Transport Emissions from Sofia’s Streets—Inventory, Scenarios, and Exposure Setting. In Environmental Protection and Disaster Risks; Dobrinkova, N., Nikolov, O., Eds.; EnviroRISKs 2022: Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomenko, S.; Burov, A.; Dzhambov, A.M.; de Hoogh, K.; Helbich, M.; Mijling, B.; Hlebarov, I.; Popov, I.; Dimitrova, D.; Dimitrova, R.; et al. Health Burden and Inequities of Urban Environmental Stressors in Sofia, Bulgaria. Environ. Res. 2025, 279, 121782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezov, D.; Burov, A. Ensemble Learning Traffic Model for Sofia: A Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Jin, B.; Wang, T.; Qian, S.; Zou, J.; Dinh, V.N.T.; Jaffrezo, J.L.; Uzu, G.; Dominutti, P.; et al. Source Apportionment of PM10 Based on Offline Chemical Speciation Data at 24 European Sites. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mircea, M.; Calori, G.; Pirovano, G.; Belis, C.A. European guide on air pollution source apportionment for particulate matter with source oriented models and their combined use with receptor models. In EUR 30082 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; ISBN 978-92-76-10698-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, F.; Kotthoff, L.; Vanschoren, J. Automated Machine Learning: Methods, Systems, Challenges; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; ISBN 9783030053185. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, N.; Mueller, J.W.; Shirkov, A.; Zhang, H.; Larroy, P.; Li, M.; Smola, A. AutoGluon-Tabular: Robust and Accurate AutoML for Structured Data. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganaie, M.A.; Hu, M.; Malik, A.K.; Tanveer, M.; Suganthan, P.N. Ensemble Deep Learning: A Review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 115, 105151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gospodinov, I.; Tsenova, B. Some weather and climate facts for year 2020 in Bulgaria—Based on the Annual hydro-meteorological bulletin of NIMH. Bul. J. Meteo Hydro 2021, 25, 72–88. [Google Scholar]

- NIMH. The Changing Climate of Bulgaria—Data and Analyses; Marinova, T., Bocheva, L., Eds.; NIMH: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2023; ISBN 978-954-90537-3-9. (In Bulgarian). Available online: https://www.meteo.bg/meteo7/sites/storm.cfd.meteo.bg.meteo7/files/kniga_klim_promeni_23-12-2023_KM_ff.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Benali, F.; Bodénès, D.; Labroche, N.; de Runz, C. MTCopula: Synthetic complex data generation using copula. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Workshop on Design, Optimization, Languages and Analytical Processing of Big Data (DOLAP ‘21), Nicosia, Cyprus, 23 March 2021; pp. 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Masarotto, G.; Varin, C. Gaussian Copula Marginal Regression. Electron. J. Statist. 2012, 6, 1517–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgo, L.; Ribeiro, R.P.; Pfahringer, B.; Branco, P. SMOTE for Regression. In Progress in Artificial Intelligence, Proceedings of the 16th Portuguese Conference on Artificial Intelligence, EPIA 2013, Angra do Heroísmo, Portugal, 9–13 September 2013, Proceedings; Correia, L., Reis, L.P., Cascalho, J., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 8154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal Component Analysis: A Review and Recent Developments. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linda, J.; Uhlík, O.; Köbölová, K.; Pospíšil, J.; Apeltauer, T. Recognition of Wind-Induced Resuspension of PM10 and Its Fractions PM10-2.5, PM2.5-1, and PM1 in Urban Environments. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boga, R.; Keresztesi, Á.; Bodor, Z.; Tonk, S.; Szép, R.; Micheu, M.M. Source identification and exposure assessment to PM10 in the Eastern Carpathians, Romania. J. Atmos. Chem. 2021, 78, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linda, J.; Pospíšil, J.; Köbölová, K.; Ličbinský, R.; Huzlík, J.; Karel, J. Conditions Affecting Wind-Induced PM10 Resuspension as a Persistent Source of Pollution for the Future City Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagulian, F.; Belis, C.A.; Dora, C.F.C.; Prüss-Ustün, A.M.; Bonjour, S.; Adair-Rohani, H.; Amann, M. Contributions to Cities’ Ambient Particulate Matter (PM): A Systematic Review of Local Source Contributions at Global Level. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 120, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.; Sokhi, R.; Ravindra, K.; Mao, H.; Prain, H.D.; Bull, I.D. Source apportionment of traffic emissions of particulate matter using tunnel measurements. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 77, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.; Dimitrova, V.; Germanova, N.; Burov, A.; Brezov, D.; Hlebarov, I.; Dimitrova, R. Joint associations and pathways from greenspace, traffic-related air pollution, and noise to poor self-rated general health: A population-based study in Sofia, Bulgaria. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesaresi, M.; Schiavina, M.; Politis, P.; Freire, S.; Krasnodębska, K.; Uhl, J.H.; Carioli, A.; Corbane, C.; Dijkstra, L.; Florio, P.; et al. Advances on the Global Human Settlement Layer by Joint Assessment of Earth Observation and Population Survey Data. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2390454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comprehensive Program for Improving the Quality of Atmospheric Air of Sofia Municipality for the Period 2021–2026. Available online: https://www.sofia.bg/components-environment-air (accessed on 23 June 2025). (In Bulgarian).

| Feature | Data Description | Missing |

|---|---|---|

| PM10 | aerosol 10 μm particulate matter levels (daily average) | |

| NO2 | aerosol nitrogen dioxide concentration (daily average) | |

| SO2 | aerosol sulfur dioxide concentration (daily average) | |

| O3 | aerosol ozone concentration (daily average) | |

| humidity | air humidity (daily average) | |

| bare soil | estimated area of bare soil spots within a r = 250 m radius (based on satellite data) | - |

| sun rad. 1 | sun radiation (daily average) | |

| NO 1 | aerosol nitrogen oxide concentration (daily average) | |

| actuse | heatmap with r = 200 m of estimated motorized users (POI and cadastral data based) | - |

| wood | estimated density of wood stove user pixels within a r = 500 m radius | - |

| coal | estimated density of coal stove user pixels within a r = 500 m radius | - |

| traffic18 | IDW-interpolated mean traffic spatial distribution model for 2018 | - |

| traffic22 | IDW-interpolated mean traffic spatial distribution model for 2022 | - |

| light | estimated contribution of light vehicles (cars) to the traffic | - |

| heavy | estimated contribution of heavy vehicles (trucks, etc.) to the traffic | - |

| Model | model0 | model1 | model1 + PCA | model2 + PCA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WeightedEnsemble_L3 | ||||

| ExtraTreesMSE_BAG_L2 | − | − | ||

| RandomForestMSE_BAG_L2 | ||||

| CatBoost_BAG_L2 | ||||

| NeuralNetFastAI_BAG_L2 | − | − | ||

| LightGBM_BAG_L2 | ||||

| WeightedEnsemble_L2 |

| Model | model0 | model1 | model2 | Mean Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO2 | 7–11% | |||

| O3 | 18–23% | |||

| SO2 | 5–18% | |||

| actuse | 4–7% | |||

| humidity | 9–26% | |||

| bare soil | 1–4% | |||

| coal | 3–7% | |||

| wood | 3–17% | |||

| traffic22 | 15–28% | |||

| traffic18 | 2–23% | |||

| heavy | 2–5% | |||

| light | 8–15% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brezov, D.; Dimitrova, R.; Burov, A.; Dimova, L.; Angelova-Koevska, P.; Georgiev, S.; Hristova, E. Analyzing the Contribution of Bare Soil Surfaces to Resuspended Particulate Matter in Urban Areas via Machine Learning. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12783. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312783

Brezov D, Dimitrova R, Burov A, Dimova L, Angelova-Koevska P, Georgiev S, Hristova E. Analyzing the Contribution of Bare Soil Surfaces to Resuspended Particulate Matter in Urban Areas via Machine Learning. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12783. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312783

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrezov, Danail, Reneta Dimitrova, Angel Burov, Lyuba Dimova, Petya Angelova-Koevska, Stoyan Georgiev, and Elena Hristova. 2025. "Analyzing the Contribution of Bare Soil Surfaces to Resuspended Particulate Matter in Urban Areas via Machine Learning" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12783. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312783

APA StyleBrezov, D., Dimitrova, R., Burov, A., Dimova, L., Angelova-Koevska, P., Georgiev, S., & Hristova, E. (2025). Analyzing the Contribution of Bare Soil Surfaces to Resuspended Particulate Matter in Urban Areas via Machine Learning. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12783. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312783