Development of a Coastal Erosion Monitoring Plan Using In Situ Measurements and Satellite Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

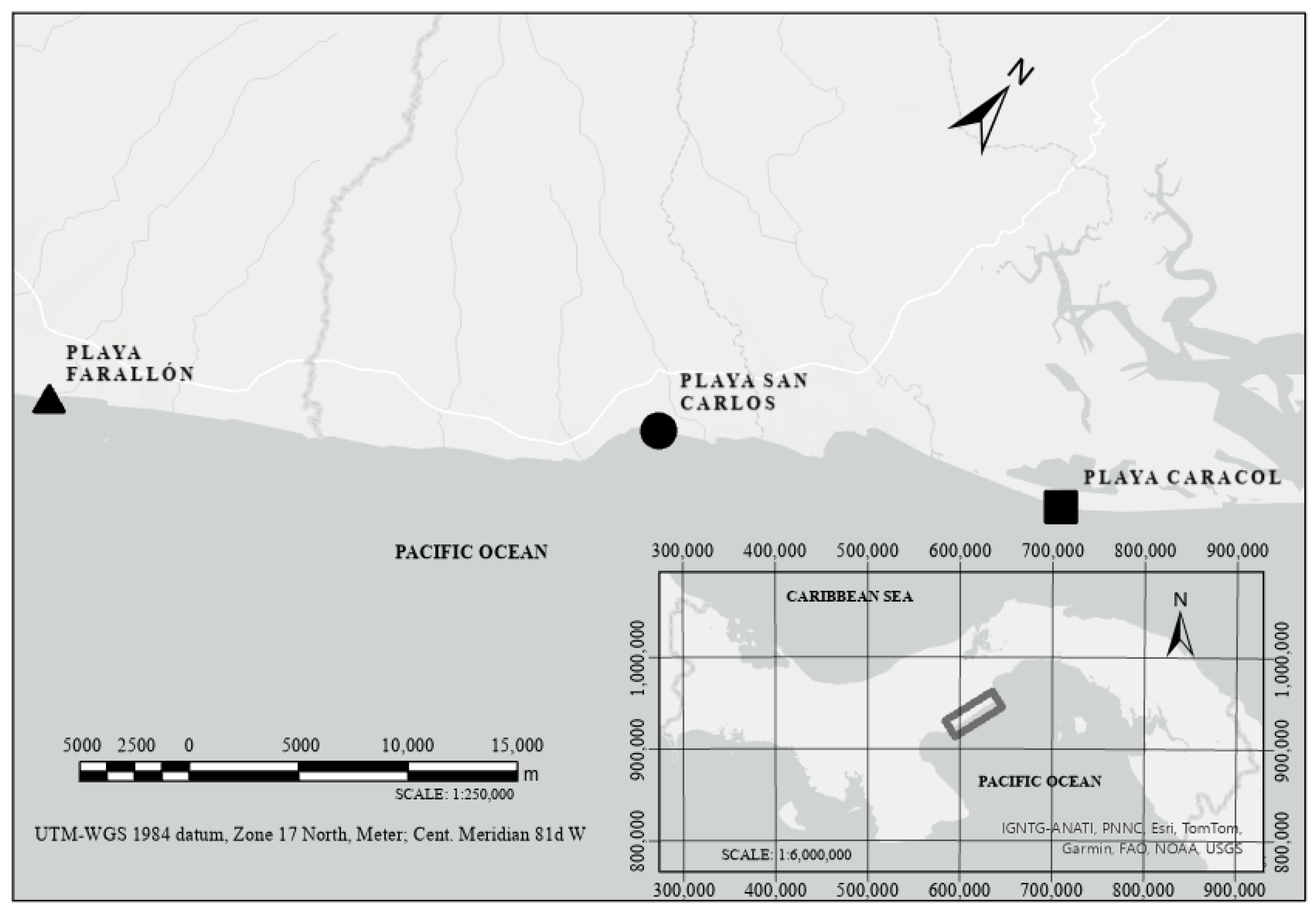

2.1. Study Area

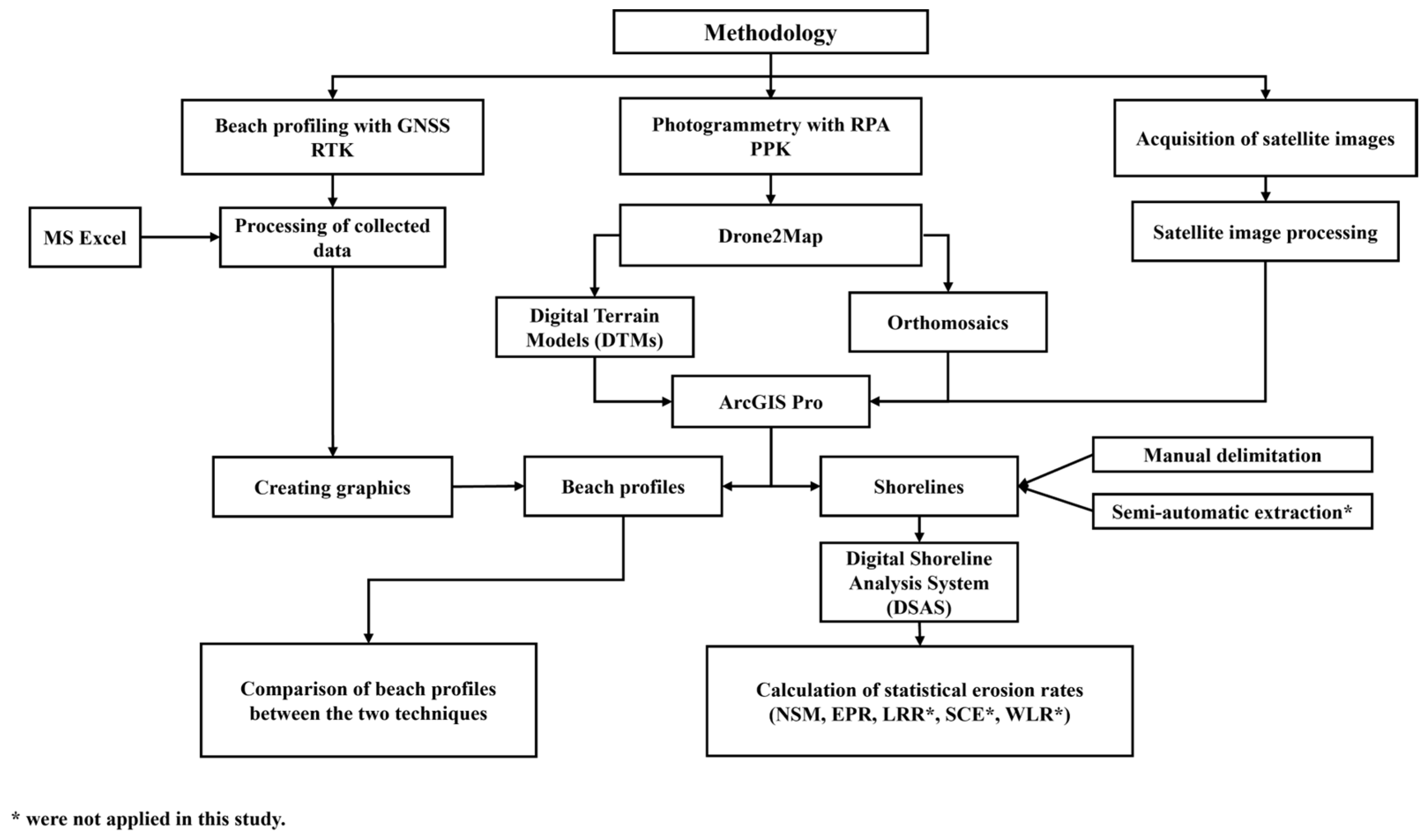

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Data Collection

Beach Profile Surveying with Differential GNSS RTK

Photogrammetry with RPA PPK

2.2.2. Data Analysis

Estimating Coastal Erosion Using the DSAS Tool

- Short-term monitoring

- Long-term monitoring

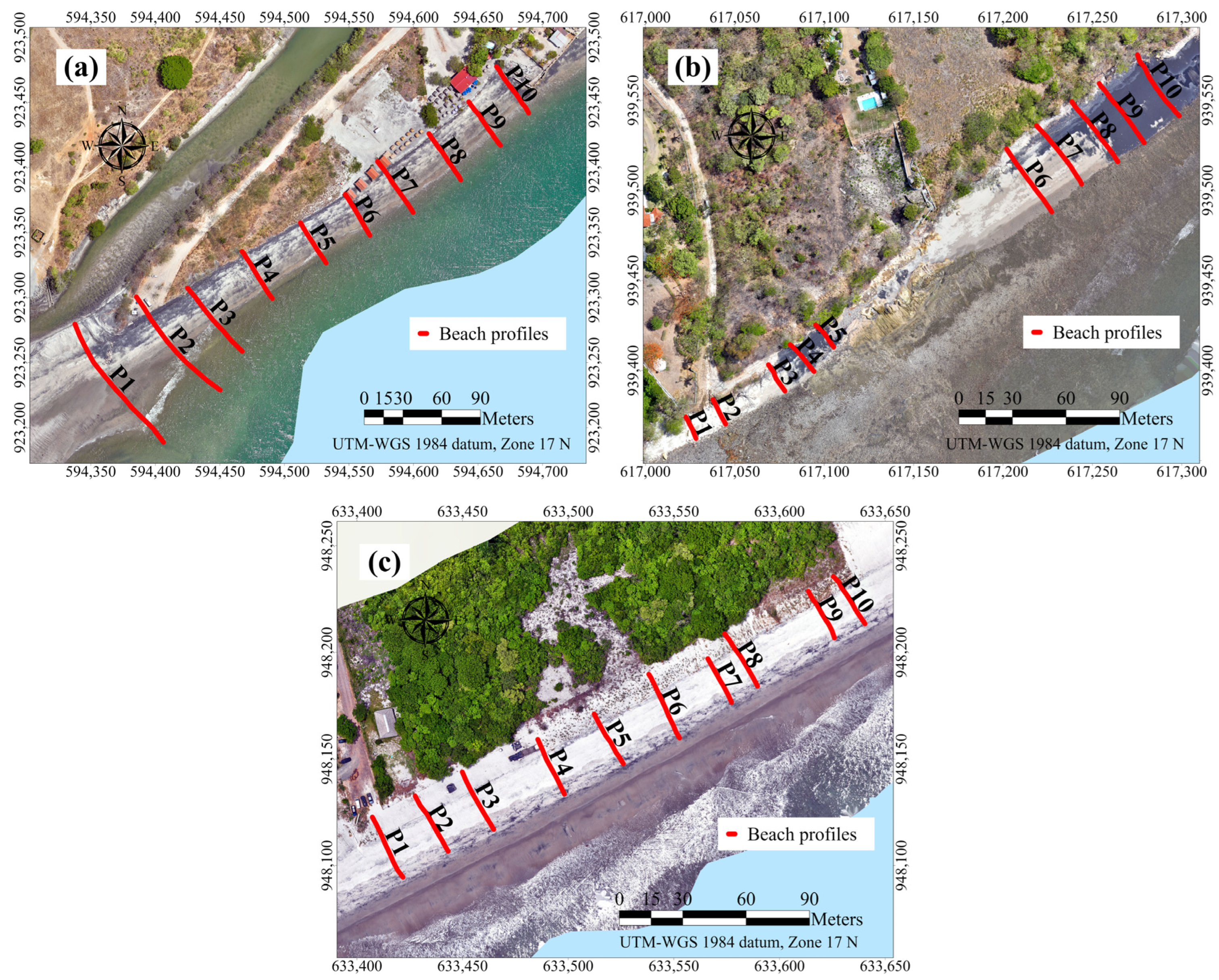

Beach Profiles Monitoring

3. Results

3.1. Estimating Coastal Erosion

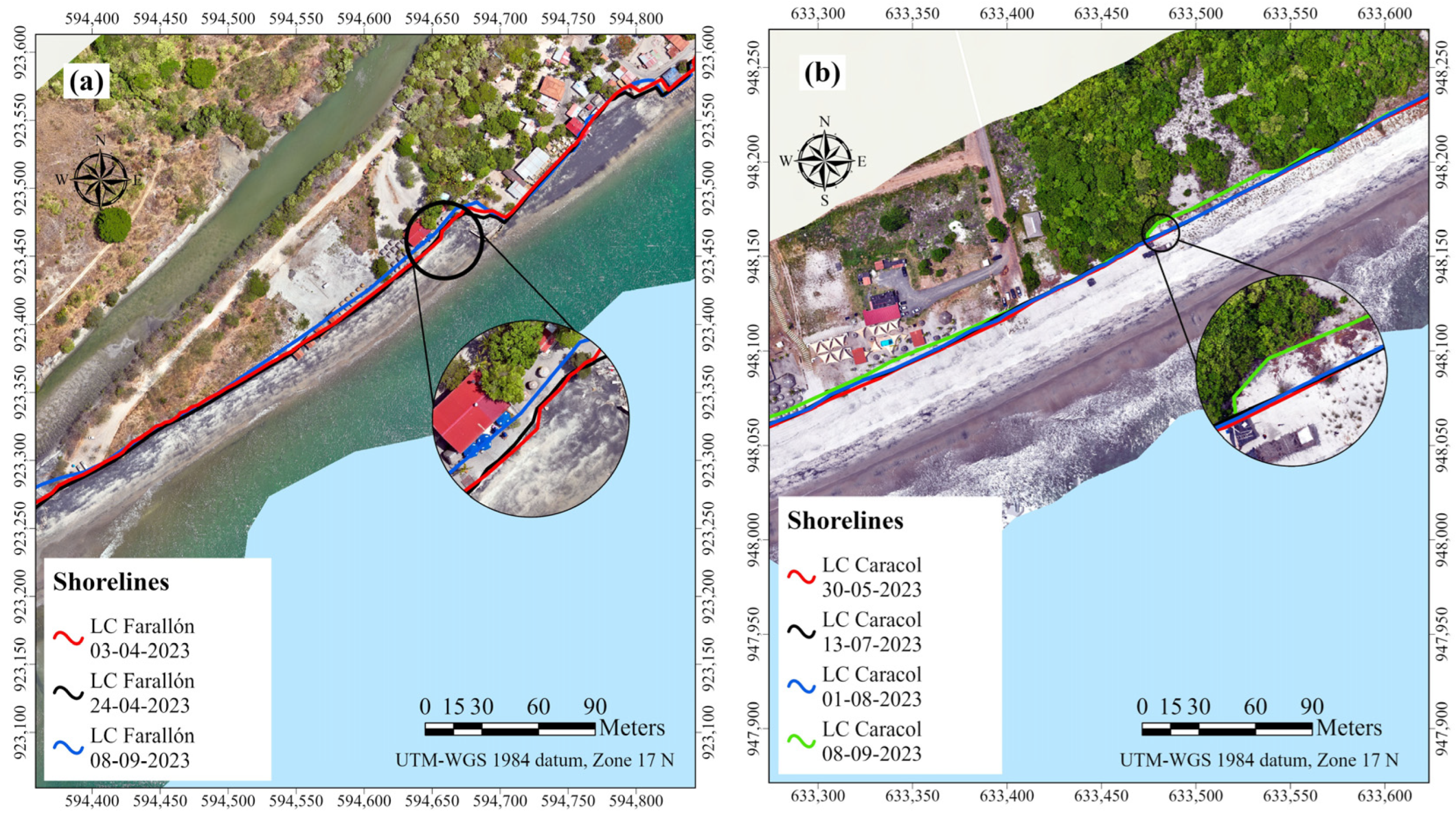

3.1.1. Short-Term Monitoring

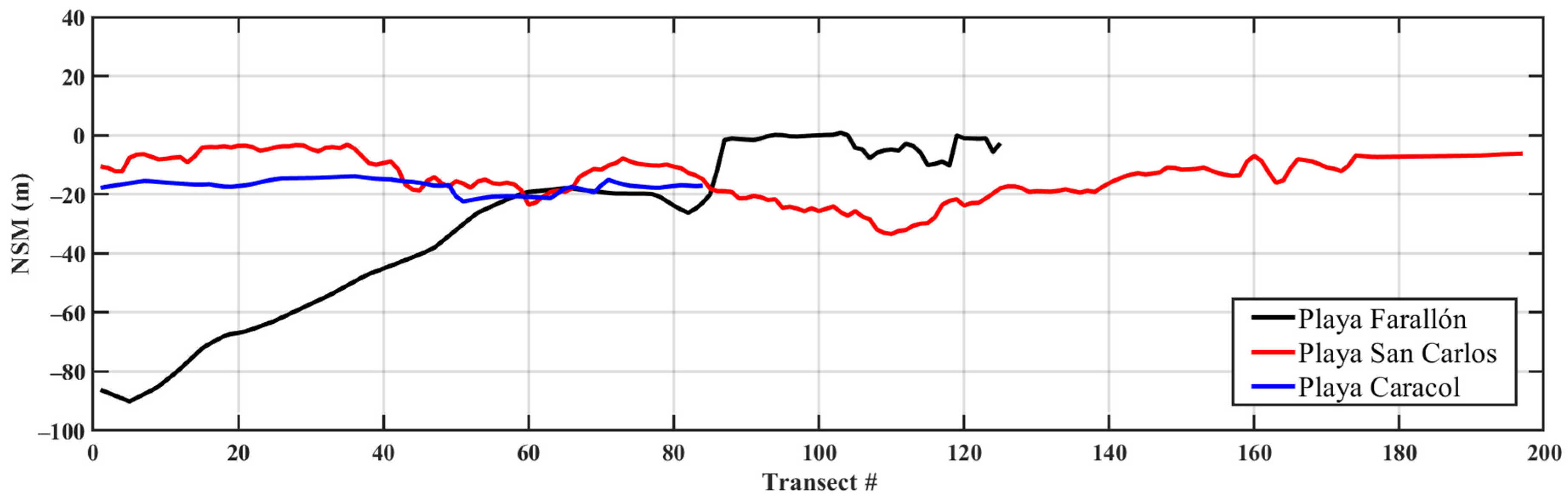

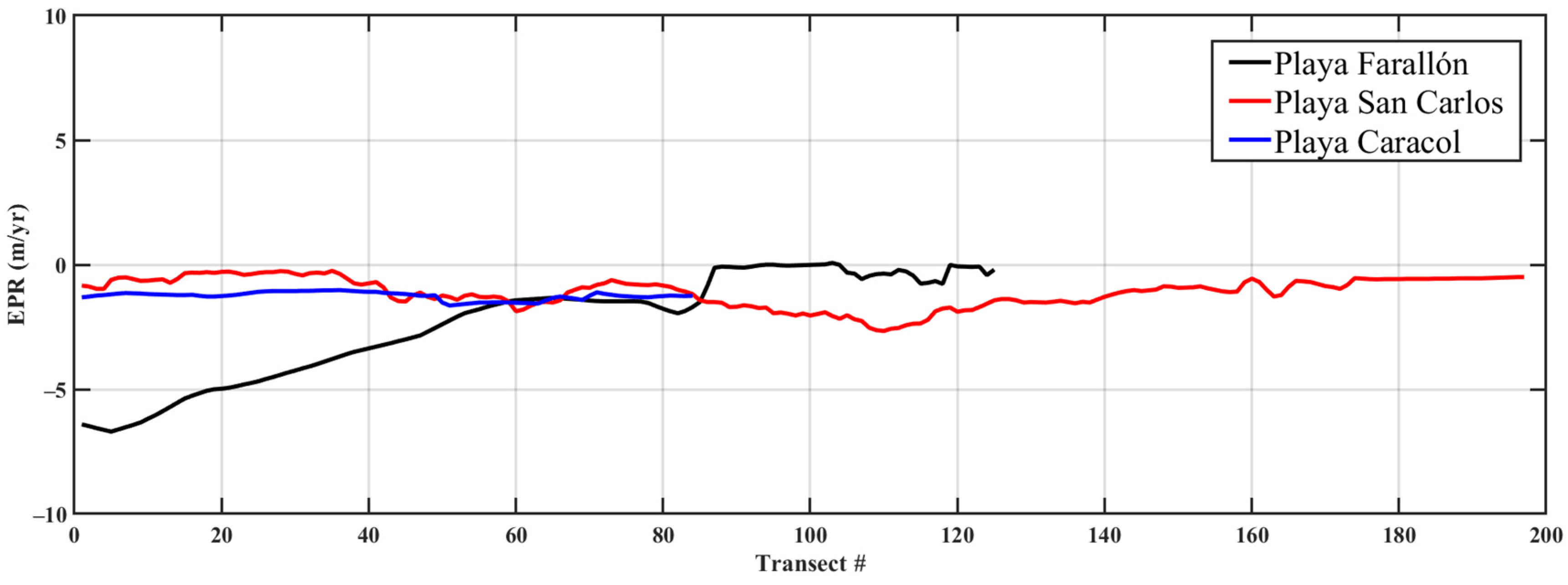

3.1.2. Long-Term Monitoring

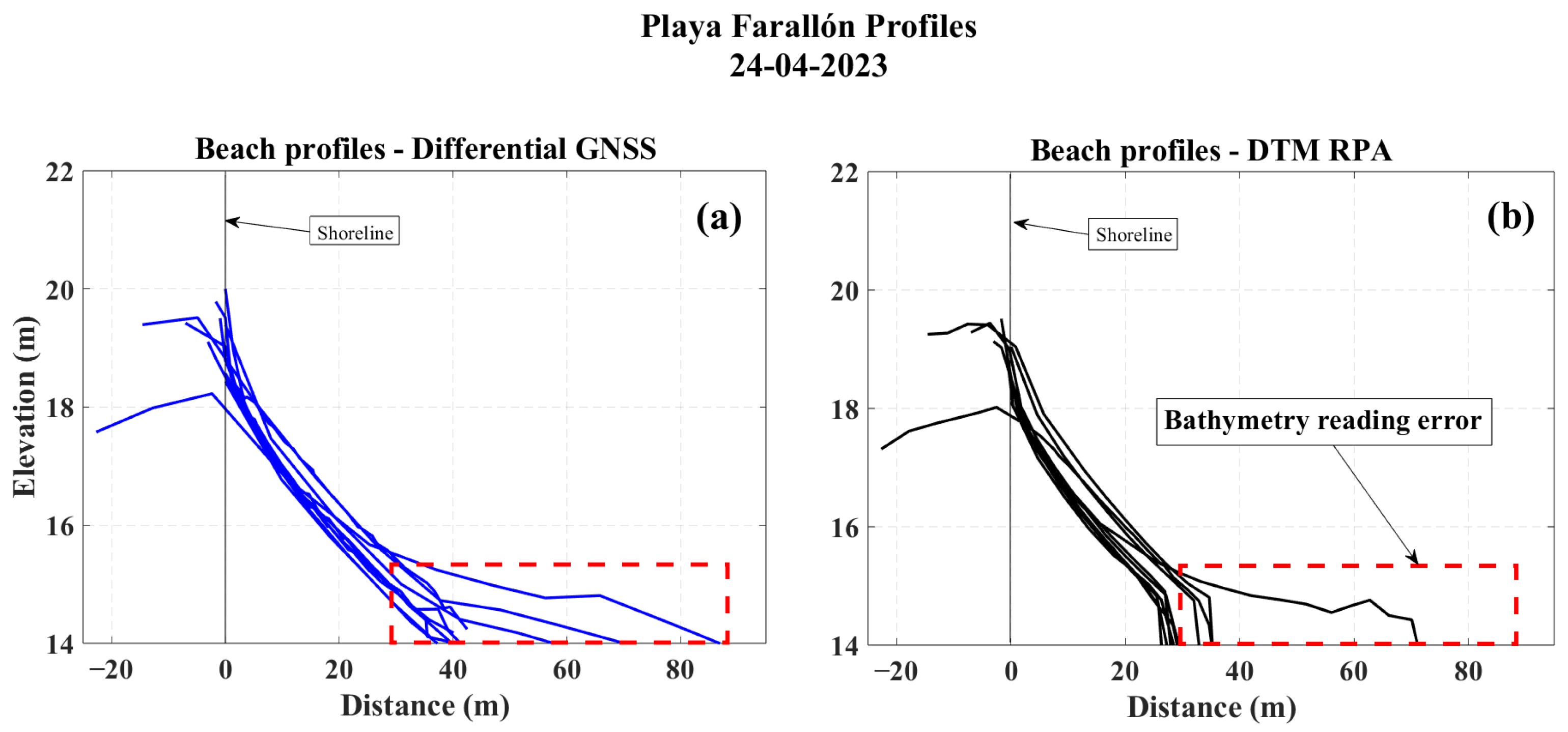

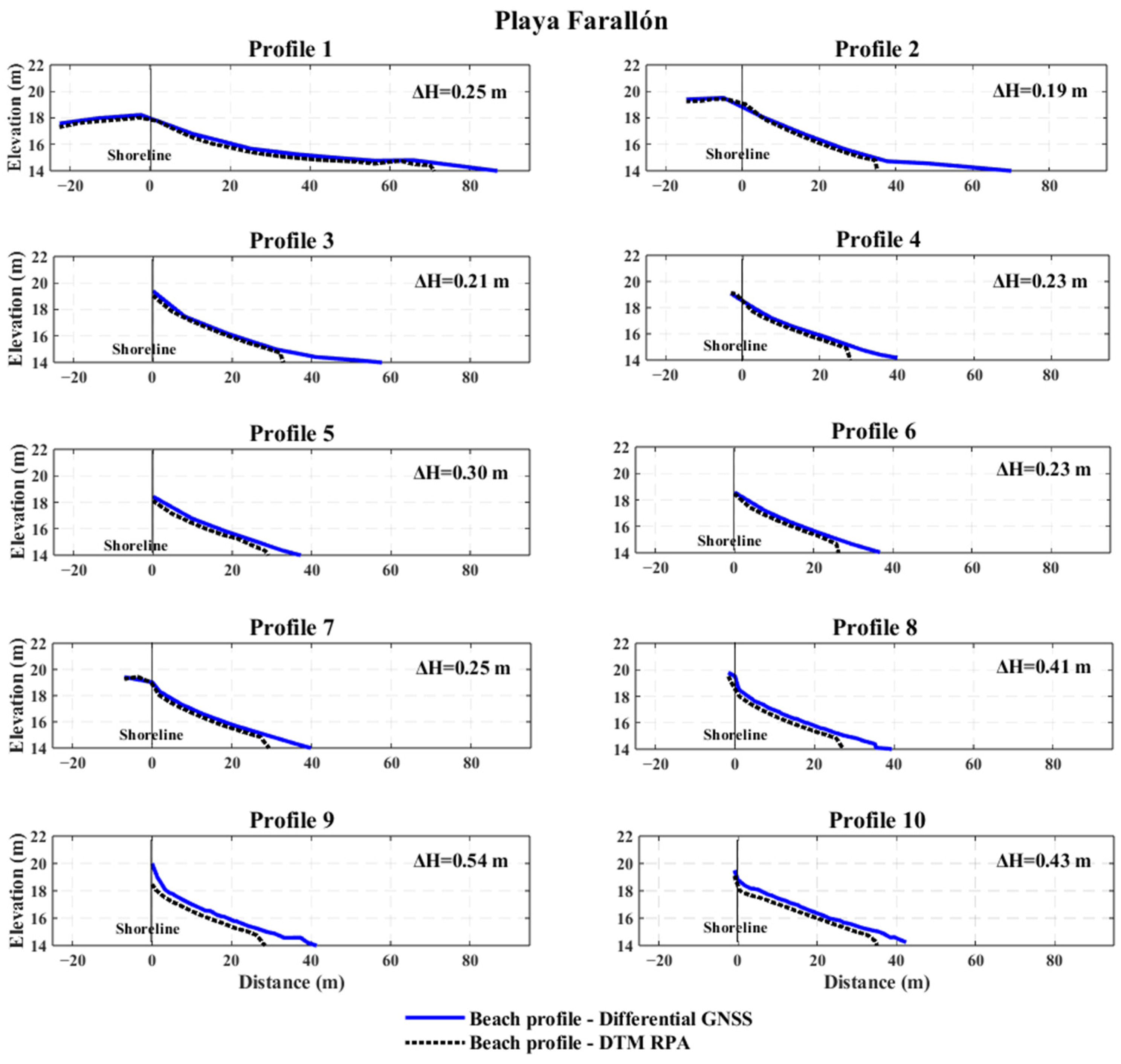

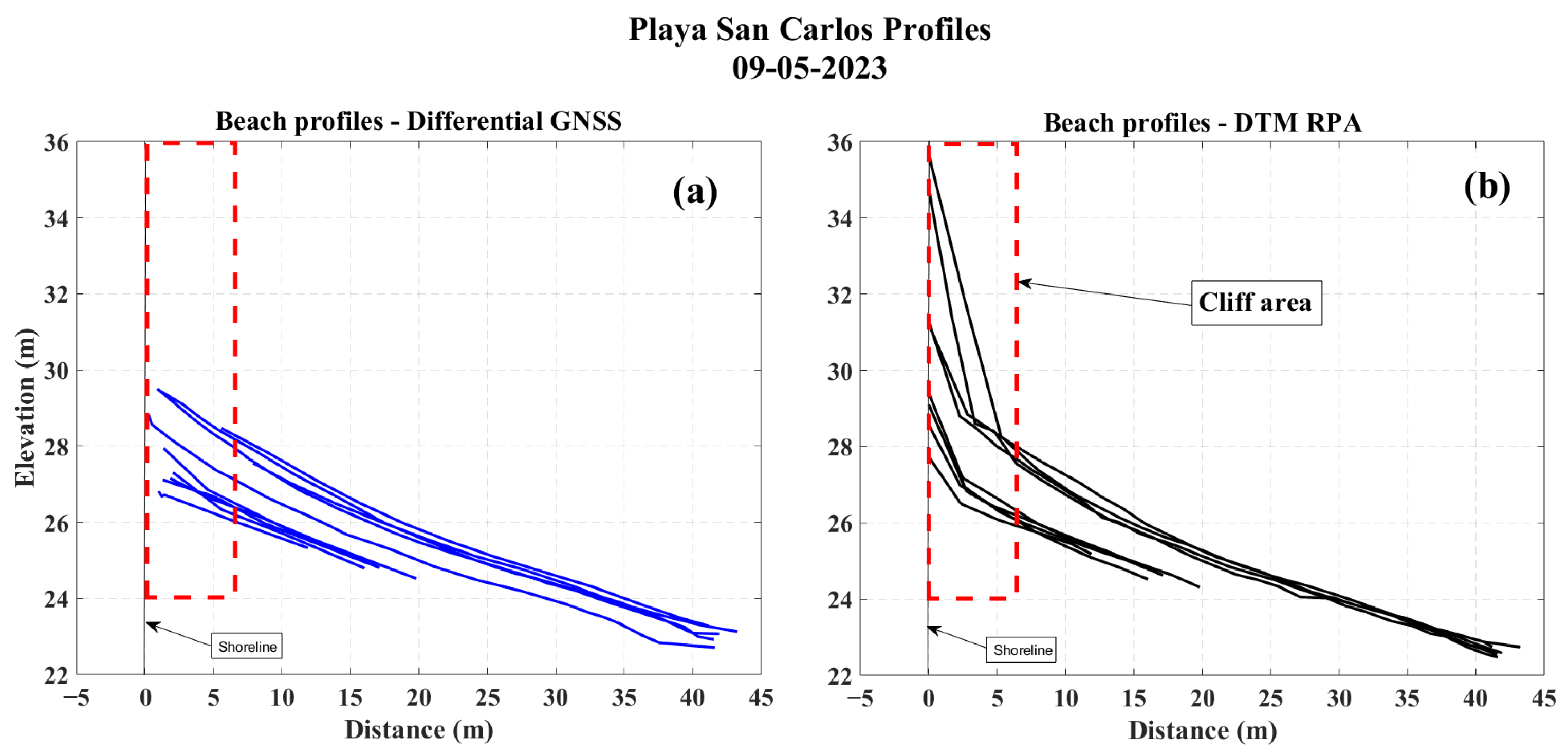

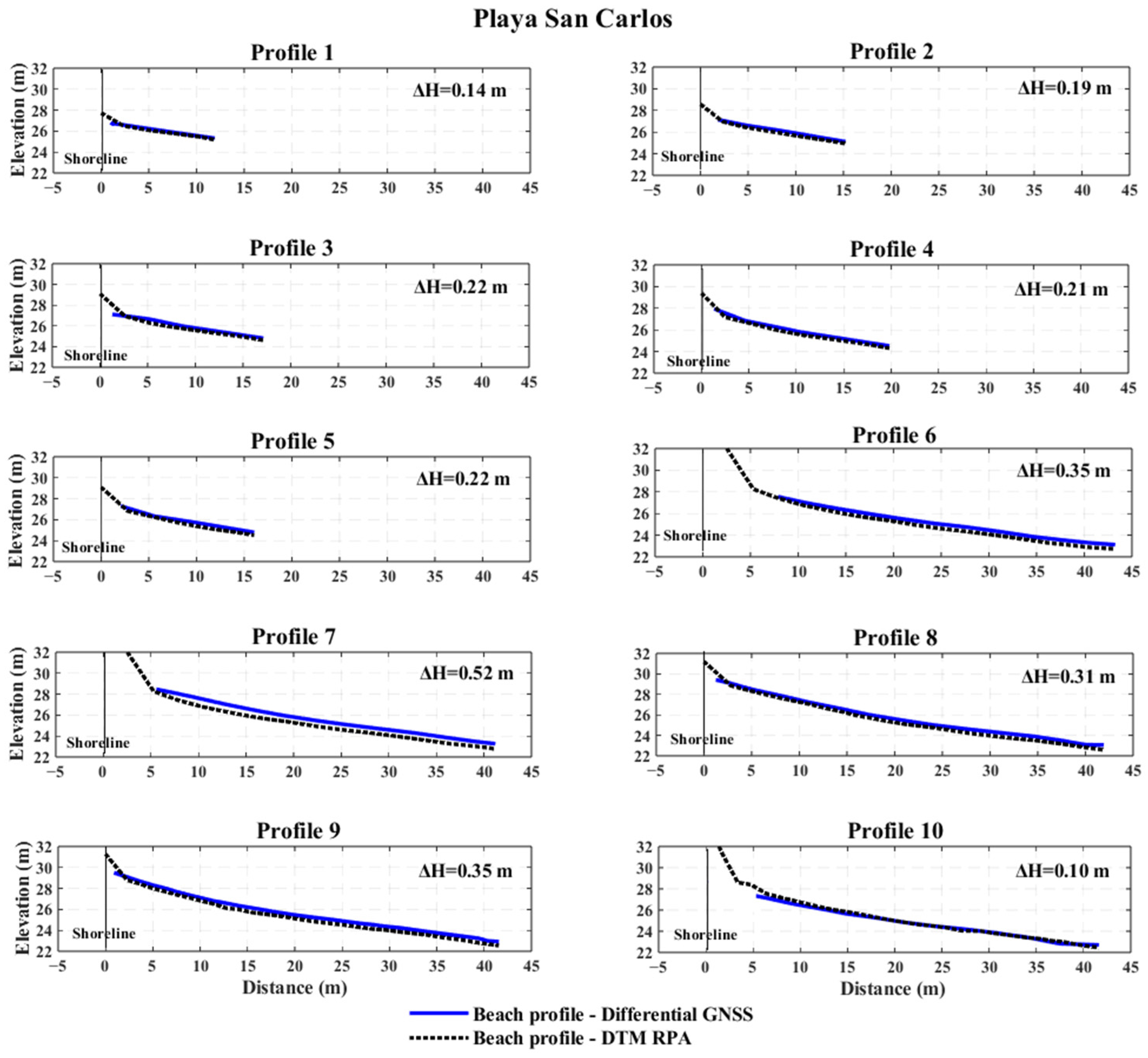

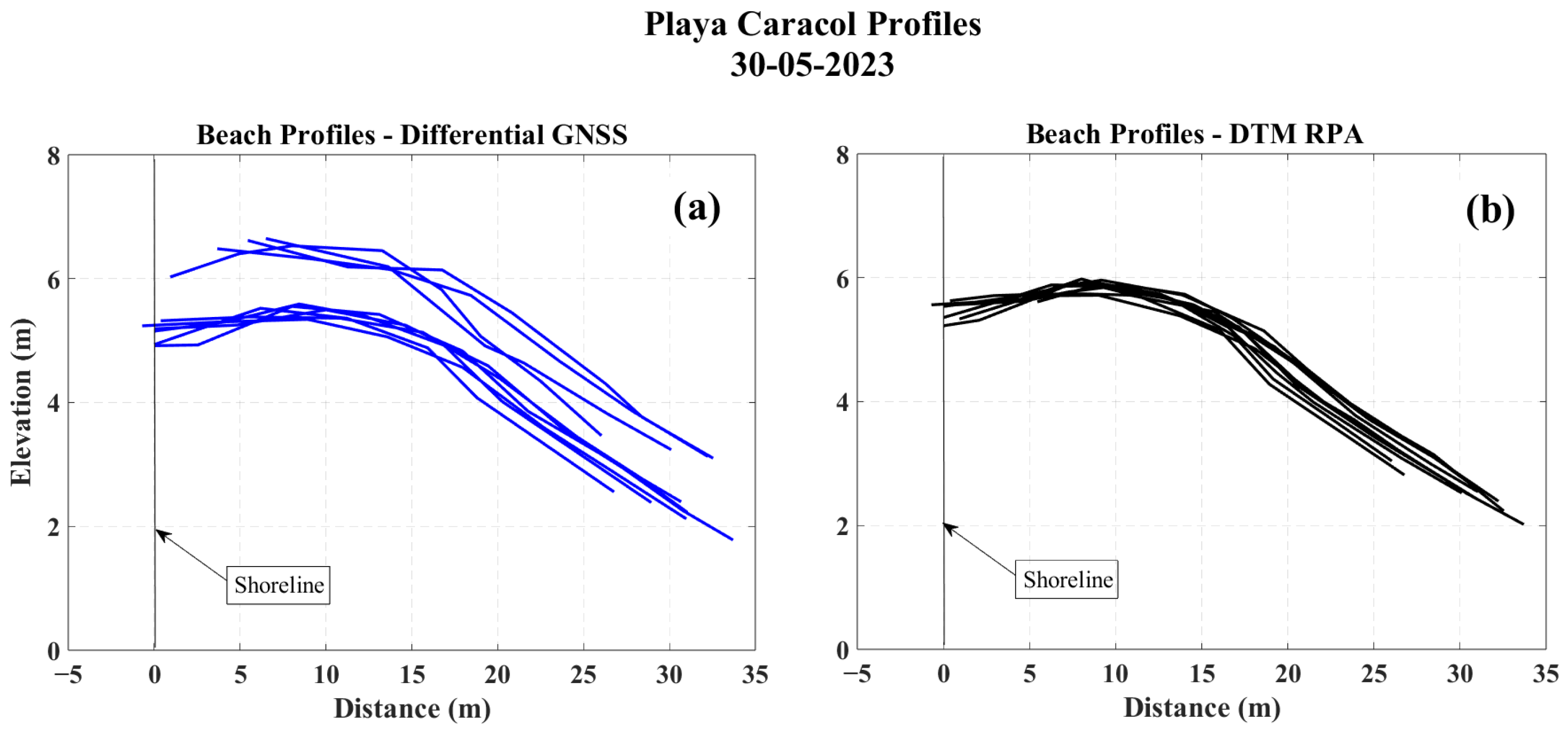

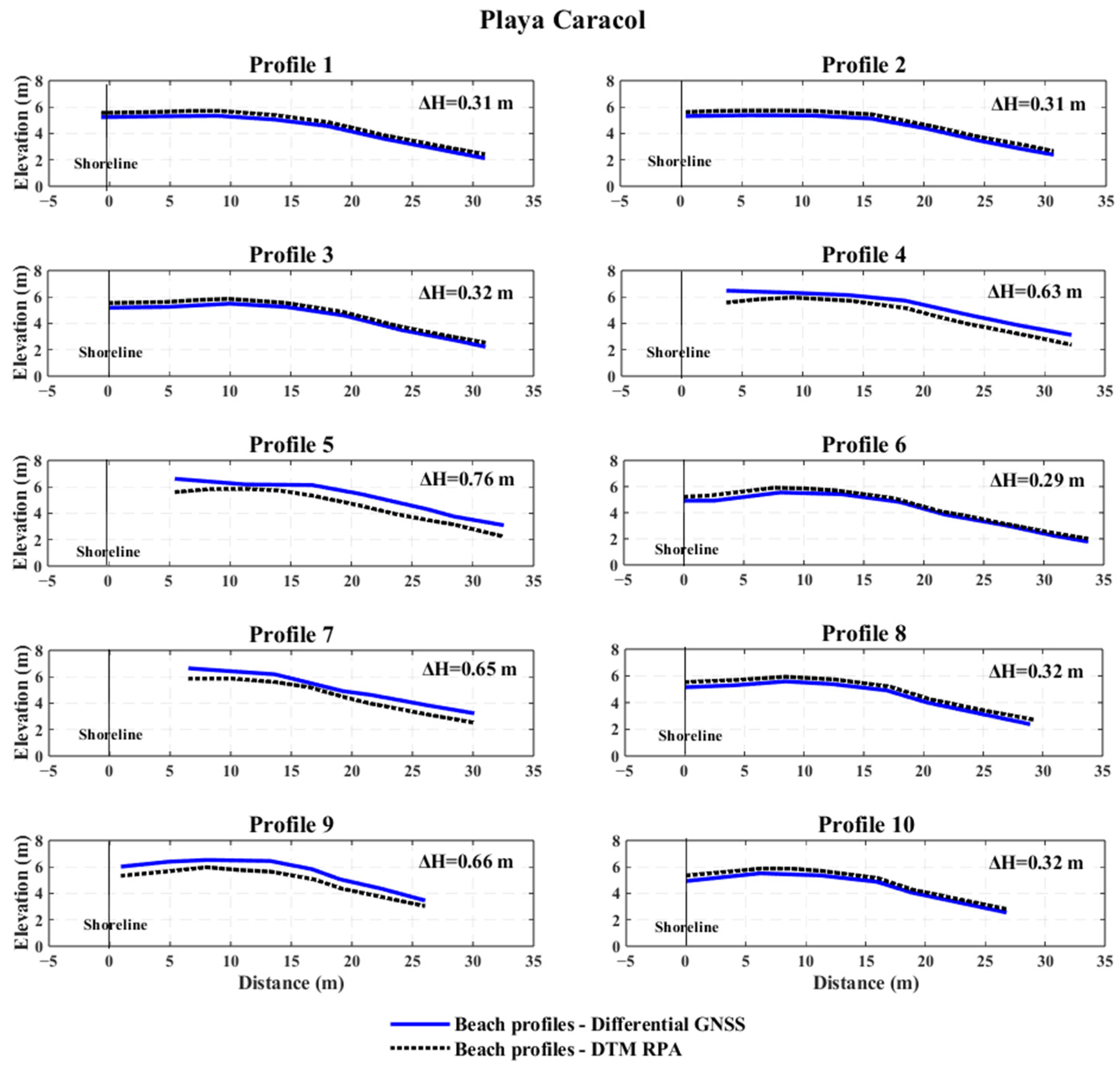

3.2. Beach Profiles Comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis and Discussion of Results

4.1.1. Coastal Erosion

4.1.2. Beach Profiles

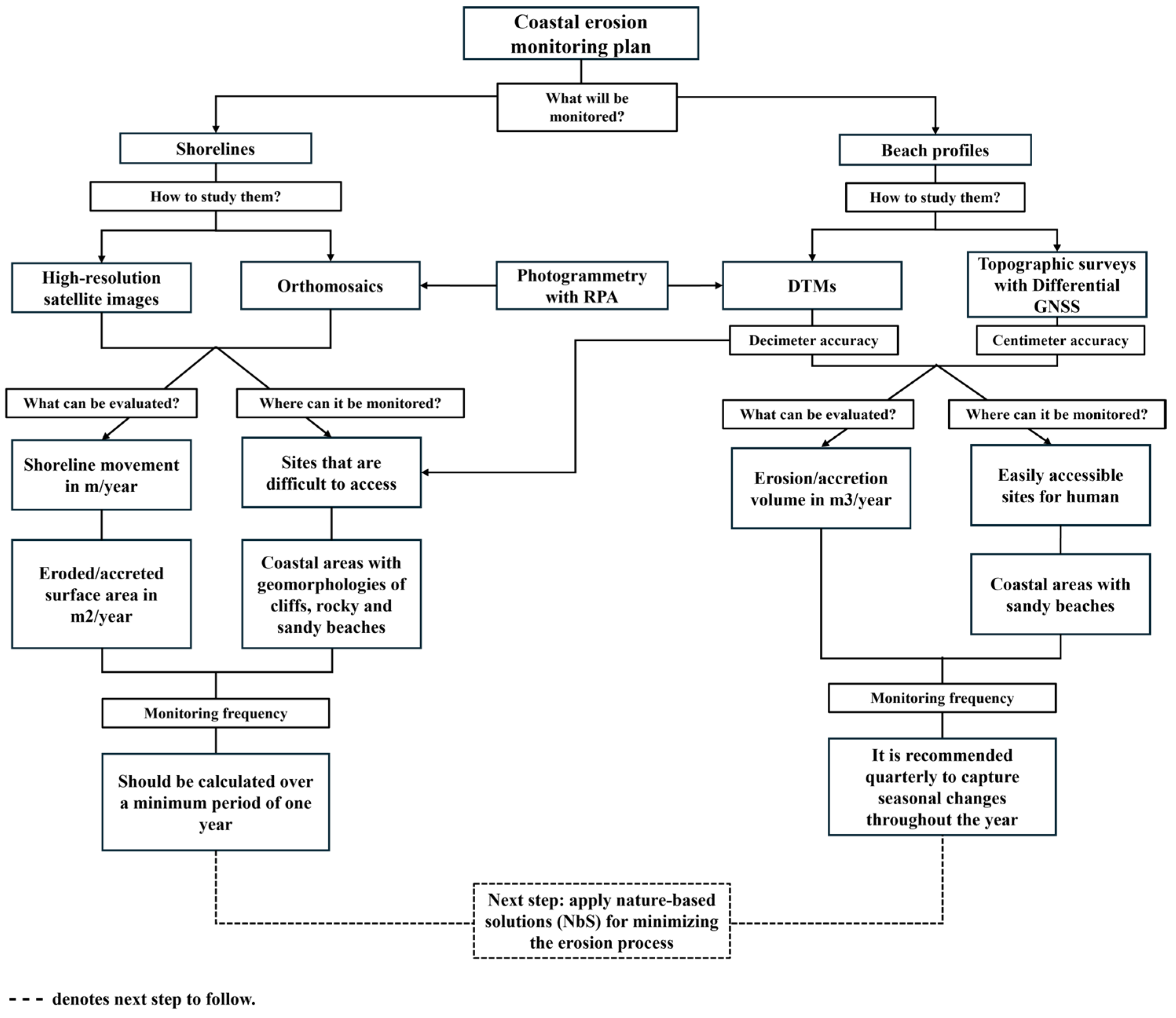

4.2. Coastal Erosion Monitoring Plan

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barrantes-Castillo, G.; Arozarena-Llopis, I.; Sandoval-Murillo, L.F.; Valverde-Calderón, J.F. Playas Críticas Por Erosión Costera En El Caribe Sur de Costa Rica, Durante El Periodo 2005–2016. Rev. Geogr. Am. Cent. 2019, 1, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mahdy, M.E.-S.; Saber, A.; Moursy, F.E.; Sharaky, A.; Saleh, N. Coastal Erosion Risk Assessment and Applied Mitigation Measures at Ezbet Elborg Village, Egyptian Delta. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucho-Maloof, I.E.; Otero-Díaz, L.J.; Cueto-Fonseca, J.E. Recent Changes in the Coastline between Bocas de Ceniza and Puerto Velero (Atlántico, Colombia). Bol. Geol. 2022, 44, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido Aldana, P.; Ramírez Camperos, A.; Godínez Orta, L.; Cruz León, S. Estudio de La Erosión Costera En Cancún y La Riviera Maya, México. Av. Recur. Hídr. 2009, 20, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tassara, D.; García, M. Erosión Marina, Vulnerabilidad de Impactos Antrópicos En El Sudeste Bonaerense. Tiempo Espac. 2015, 15, 113–126. Available online: https://revistas.ubiobio.cl/index.php/TYE/article/view/1695 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Lizano, R.O.G. Erosión En Las Playas de Costa Rica, Incluyendo La Isla Del Coco. InterSedes 2013, 14, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luijendijk, A.; Hagenaars, G.; Ranasinghe, R.; Baart, F.; Donchyts, G.; Aarninkhof, S. The State of the World’s Beaches. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. IPCC Fourth Assessment Report: Climate Change 2007. Report of Working Group II—Impact, Adaptation and Vulnerability; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval-Murillo, L.; Barrantes-Castillo, G. Changes in Land Cover in Coastal Erosion Hotspots in the Southern Caribbean of Costa Rica, during the 2005–2017 Period. Uniciencia 2021, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina Gil, R.; Anfuso, G.; Manno, G. El Litoral Mediterráneo Andaluz: Características, Evolución y Respuesta Frente a Los Procesos Naturales y Las Actuaciones Antrópicas. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Cádiz, Cádiz, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vallarino Castillo, R.; Negro Valdecantos, V.; del Campo, J.M. Understanding the Impact of Hydrodynamics on Coastal Erosion in Latin America: A Systematic Review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1267402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez Calero, N.M.; Magaña Monge, A.O.; Soriano Melgar, E. Análisis Comparativo Entre Levantamientos Topográficos Con Estación Total Como Método Directo y El Uso de Drones y GPS Como Métodos Indirectos; Universidad de El Salvador: San Salvador, El Salvador, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lappe, R.; Ullmann, T.; Bachofer, F. State of the Vietnamese Coast—Assessing Three Decades (1986 to 2021) of Coastline Dynamics Using the Landsat Archive. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda Zújar, J. Métodos Para El Cálculo de La Erosión Costera. Revisión, Tendencias y Propuesta. Bol. Asoc. Geógr. Esp. 2000, 30, 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Vallarino Castillo, R.; Negro Valdecantos, V.; Moreno Blasco, L. Shoreline Change Analysis Using Historical Multispectral Landsat Images of the Pacific Coast of Panama. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.; Avila, G.; Guerra-Chanis, G. Coastline Changes in the Pacific of Panama Due to Coastal Erosion. In Proceedings of the 2022 8th International Engineering, Sciences and Technology Conference, IESTEC 2022, Panama City, Panama, 19–21 October 2022; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yue, P.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, X.; Guo, Z. Field Erosion Protection of Tidal Beach: Comparison and Synergy between Sulfide Aluminum Cementing Materials and Biomineralization Materials. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e04092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Rui, S. Field Implementation to Resist Coastal Erosion of Sandy Slope by Eco-Friendly Methods. Coast. Eng. 2024, 189, 104489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute Physical Monitoring—GIS Laboratory. STRI GIS Portal. Available online: https://stridata-si.opendata.arcgis.com/maps/fdadd3da67ec4ab4a3045e218256b303/explore?location=7.949267%2C-79.694149%2C10 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Grimaldo, M.A. Plano de Las Olas Del Golfo de Panamá. Tecnociencia 2014, 16, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Buzard, R.M.; Overbeck, J.R.; Maio, C.V. Community-Based Methods for Monitoring Coastal Erosion. Alsk. Div. Geol. Geophys. Surv. Inf. Circ. 2019, 84, 30182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González G., F.E.; Laguna, D. Análisis de La Estimación Del Índice de Vulnerabilidad Costera de Panamá Oeste Mediante Sistemas de Información Geográfica. Synergía 2023, 2, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boak, E.H.; Turner, I.L. Shoreline Definition and Detection: A Review. J. Coast. Res. 2005, 214, 688–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łabuz, T.A. A Review of Field Methods to Survey Coastal Dunes—Experience Based on Research from South Baltic Coast. J. Coast. Conserv. 2016, 20, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchi, E.; Tavasci, L.; De Nigris, N.; Gandolfi, S. Gnss and Photogrammetric Uav Derived Data for Coastal Monitoring: A Case of Study in Emilia-Romagna, Italy. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, S.; Hariyanto, T. Analysis of the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Accuracy Using Post-Processing Kinematic (PPK) Method for Measuring the Situation of Open Pit Mining in PT. Berau Coal. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Geoscience, Electronics and Remote Sensing Technology: Global Challenges in Geoscience, Electronics, and Remote Sensing: Future Directions in City, Land, and Ocean Sustainable Development, AGERS 2023, Surabaya, Indonesia, 19–20 December 2023; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddia, Y.; Stecchi, F.; Pellegrinelli, A. Coastal Mapping Using Dji Phantom 4 RTK in Post-Processing Kinematic Mode. Drones 2020, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmelstoss, E.A.; Henderson, R.E.; Kratzmann, M.G.; Farris, A.S. Digital Shoreline Analysis System (DSAS) Version 5.1 User Guide; Open-File Report 2021–1091; U.S. Geological Survey: Woods Hole, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentaschi, L.; Vousdoukas, M.I.; Pekel, J.F.; Voukouvalas, E.; Feyen, L. Global Long-Term Observations of Coastal Erosion and Accretion. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzeda, F.; Ortega, L.; Costa, L.L.; Fanini, L.; Barboza, C.A.M.; McLachlan, A.; Defeo, O. Global Patterns in Sandy Beach Erosion: Unraveling the Roles of Anthropogenic, Climatic and Morphodynamic Factors. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1270490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Sun, Y.; Liu, R.; Wei, X.; Li, Z. Evaluation of the Applicability of Beach Erosion and Accretion Index in Qiongzhou Strait of China. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1453439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, E.T.; Jiménez, J.A. Storm-Induced Beach Erosion Potential on the Catalonian Coast. J. Coast. Res. 2006, 48, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lobeto, H.; Semedo, A.; Lemos, G.; Dastgheib, A.; Menendez, M.; Ranasinghe, R.; Bidlot, J.R. Global Coastal Wave Storminess. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, R.A.; Sallenger, A.H. Morphological Impacts of Extreme Storms on Sandy Beaches and Barriers. J. Coast. Res. 2003, 19, 560–573. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.L.; Zarillo, G.A. Calculating Long-Term Shoreline Recession Rates Using Aerial Photographic and Beach Profiling Techniques. J. Coast. Res. 1990, 6, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Casella, E.; Drechsel, J.; Winter, C.; Benninghoff, M.; Rovere, A. Accuracy of Sand Beach Topography Surveying by Drones and Photogrammetry. Geo-Mar. Lett. 2020, 40, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhrachy, I. Accuracy Assessment of Low-Cost Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Photogrammetry. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 5579–5590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.K.; Benson, A.P. Beach Profile Monitoring: How Frequent Is Sufficient? 2001. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25736322?seq=1&cid=pdf- (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Castro, V.; Guerra-Chanis, G. Implementation of Topographic Techniques for Monitoring Coastal Erosion. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Engineering, Sciences and Technology Conference, IESTEC 2024, Panama City, Panama, 23–25 October 2024; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Site | DGNSS RTK Campaign (dd-mm-yyyy) | RPA PPK Campaign (dd-mm-yyyy) |

|---|---|---|

| Playa Farallón | 24-04-2023 10-05-2023 | 03-04-2023 |

| 24-04-2023 | ||

| 08-09-2023 | ||

| Playa San Carlos | 09-05-2023 | 09-05-2023 |

| Playa Caracol | 09-02-2023 30-05-2023 01-08-2023 | 30-05-2023 |

| 13-07-2023 | ||

| 01-08-2023 | ||

| 08-09-2023 |

| Results | Playa Farallón | Playa Caracol |

|---|---|---|

| General Information | ||

| Length of shoreline studied (m) | 695 | 425 |

| Total number of transects analyzed | 125 | 84 |

| % of transects showing erosion | 60 | 98 |

| % of transects showing accretion | 34 | 1 |

| % of stable transects | 6 | 1 |

| Net Shoreline Movement (NSM) | ||

| Maximum negative movement (m) | −6.56 | −6.64 |

| Maximum positive movement (m) | 4.35 | 0.71 |

| Spatial average negative movement (m) | −3.70 | −3.26 |

| Spatial average positive movement (m) | 1.41 | 0.42 |

| End Point Rate (EPR) | ||

| Maximum erosion rate (m/yr) | −15.17 | −24.03 |

| Maximum accretion rate (m/yr) | 10.06 | 2.58 |

| Spatial average erosion rate (m/yr) | −8.88 | −11.79 |

| Standard deviation (m/yr) | 4.46 | 6.49 |

| Spatial average accretion rate (m/yr) | 3.62 | 2.58 |

| Results | Playa Farallón | Playa San Carlos | Playa Caracol |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Information | |||

| Length of shoreline studied (m) | 695 | 987 | 425 |

| Total number of transects analyzed | 125 | 197 | 84 |

| % of transects showing erosion | 69 | 89 | 100 |

| % of transects showing accretion | - | - | - * |

| % of stable transects | 31 | 11 | - |

| Net Shoreline Movement (NSM) | |||

| Maximum negative movement (m) | −90.11 | −33.48 | −22.43 |

| Maximum positive movement (m) | 0.89 | - | - |

| Spatial average negative movement (m) | −32.17 | −13.90 | −17.10 |

| Spatial average positive movement (m) | 0.25 | - | - |

| End Point Rate (EPR) | |||

| Maximum erosion rate (m/yr) | −6.70 | −2.66 | −1.64 |

| Maximum accretion rate (m/yr) | - | - | - |

| Spatial average erosion rate (m/yr) | −3.20 | −1.20 | −1.25 |

| Standard deviation(m/yr) | 1.86 | 0.55 | 0.16 |

| Spatial average accretion rate (m/yr) | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castro-Quintero, V.; Lima-Delgado, M.; Guerra-Chanis, G. Development of a Coastal Erosion Monitoring Plan Using In Situ Measurements and Satellite Images. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12769. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312769

Castro-Quintero V, Lima-Delgado M, Guerra-Chanis G. Development of a Coastal Erosion Monitoring Plan Using In Situ Measurements and Satellite Images. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12769. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312769

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastro-Quintero, Víctor, Moisés Lima-Delgado, and Gisselle Guerra-Chanis. 2025. "Development of a Coastal Erosion Monitoring Plan Using In Situ Measurements and Satellite Images" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12769. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312769

APA StyleCastro-Quintero, V., Lima-Delgado, M., & Guerra-Chanis, G. (2025). Development of a Coastal Erosion Monitoring Plan Using In Situ Measurements and Satellite Images. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12769. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312769