1. Introduction

After major nuclear accidents, such as the Fukushima-1 nuclear power plant disaster, the development of accident-tolerant fuel (ATF) systems has become one of the priority areas for improving the safety of nuclear reactors in the event of a loss-of-coolant accident (LOCA). Traditional zirconium alloys used as fuel element cladding materials react intensively with water vapor at temperatures above 1000–1200 °C, leading to high-temperature steam oxidation (HTSO). As a result, an exothermic reaction of zirconium oxidation to zirconium dioxide (Zr → ZrO

2) occurs with the release of hydrogen, which exacerbates the thermal regime of the core and contributes to the degradation of the cladding structure [

1,

2].

One of the most effective ways to increase the thermal and chemical resistance of cladding is to apply chromium-based coatings that, when heated, form a dense and adhesive-strong layer of Cr

2O

3 oxide, effectively preventing oxygen diffusion and slowing down the oxidation process of zirconium alloys in a steam environment up to temperatures of 1300 °C [

3,

4]. However, under prolonged and cyclic thermal exposure, homogeneous chromium coatings are subject to CrZr interdiffusion, the formation of brittle intermetallic phases (e.g., ZrCr

2), as well as cracking and recrystallization, which reduces their protective properties [

5,

6].

A number of researchers note that during oxidation, chromium coatings form a multilayer structure consisting of successive layers of Cr

2O

3, residual Cr, ZrCr

2 intermetallic compound, and ZrO

2 oxide from the surface to the substrate [

7,

8]. However, the mechanisms of their formation are interpreted differently. According to Brachet et al. [

9], a surface layer of Cr

2O

3 and an interphase layer of ZrCr

2 are formed at the initial stage of oxidation, and as the test time increases, oxygen diffuses along the boundaries of Cr grains, interacts with zirconium, forming ZrO

2 and causing the loss of the protective properties of the coating. Han et al. [

10] showed that chromium is completely oxidized at the early stage of vapor oxidation, after which the reduction of Cr

2O

3 by the zirconium substrate leads to the formation of subsurface layers of ZrO

2 and Cr, and further diffusion of Zr contributes to the formation of ZrCr

2 at the interface.

The oxidation resistance of chromium coatings is determined by their structure, thickness, adhesion, and level of internal stresses [

11,

12,

13,

14]. In recent years, to increase the durability and stability of the protective layer, multilayer Cr/CrN systems consisting of alternating plastic metal and hard nitride sublayers have been actively researched. This architecture helps reduce internal stresses, slow down crack propagation, create a barrier to oxygen and chromium diffusion, and limit Cr–Zr interdiffusion during vapor oxidation. According to Sidelev et al. [

15,

16], multilayer Cr/CrN coatings obtained by magnetron sputtering on zirconium alloys (e.g., E110) are characterized by higher thermal and interphase stability at temperatures up to 1400 °C compared to single-layer chromium.

However, chromium nitride (CrN) has limited thermal stability: at temperatures of around 900–1100 °C, it decomposes according to the scheme CrN → Cr

2N → Cr + N

2, which can impair the barrier properties of the coating at HTSO in the case of suboptimal parameters of the multilayer structure—sublayer thickness, period, and texture [

17]. Thus, it is the coating architecture—the number of layers, the multilayer period, and its total thickness—that plays a decisive role in ensuring structural stability and thermal stability. In addition, an important factor determining the stability of the system is the physical integrity of the layers—the absence of pores, cracks, and disruption of interlayer boundaries—which helps maintain the structural and thermal stability of the substrate under high-temperature conditions. It has been previously reported that multilayer Cr/CrN coatings effectively improve the mechanical and protective properties of various metal substrates. For example, Cai et al. [

18] studied Cr/CrN films deposited by multi-arc ion plating on Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloys. It was shown that the introduction of soft Cr interlayers disrupts the columnar growth of nitride layers, promotes the formation of CrN(200) texture, and improves wear and erosion resistance due to crack dispersion at the Cr/CrN boundaries. However, this work only considered mechanical aspects at room temperatures and did not investigate the behavior of the coatings under high-temperature oxidation conditions.

In a later study using HiPIMS technology, Li Z. et al. [

19], multilayer (CrN/Cr)ₙ coatings were produced on Zr-4 alloy, and it was found that increasing the number of layers increases the hardness (up to ~12 GPa) and resistance to steam oxidation at 1200 °C due to the formation of a fine-grained structure and a dense Cr

2O

3 oxide barrier. However, the study was limited to Zr-4 alloy and did not take into account the effect of Nb alloying, typical for operational claddings of E110 (Zr-1Nb) alloy, nor did it analyze the evolution of phases at lower temperatures typical for long-term operation in a reactor environment.

This work expands on these results and makes a new scientific contribution. For thefirst time, the influence of the architecture of multilayer Cr/CrN coatings with different numbers of layers (1, 2, 4, and 6) deposited by reactive magnetron sputtering on their structural evolution, phase stability, and thermal-oxidative behavior at 1100 °C was systematically studied for the E110 (Zr-1Nb) alloy.

In contrast to [

19,

20], the presented work is aimed at studying the architectural optimization and phase stability of multilayer Cr/CrN coatings specifically for the industrial alloy E110, which allows for a deeper understanding of the patterns of formation of barrier layers and ensures the practical application of such systems under conditions of high-temperature steam exposure.

In this regard, the aim of this work is to study the influence of the multilayer architecture of Cr/CrN coatings obtained by magnetron sputtering on the thermal stability and resistance to high-temperature vapor oxidation of zirconium alloy E110. The main focus is on investigating the influence of the number of layers on the kinetics of vapor oxidation, the morphology and evolution of the oxide film, as well as the role of multilayer architecture in suppressing interdiffusion and defects at the coating-substrate interface.

3. Results

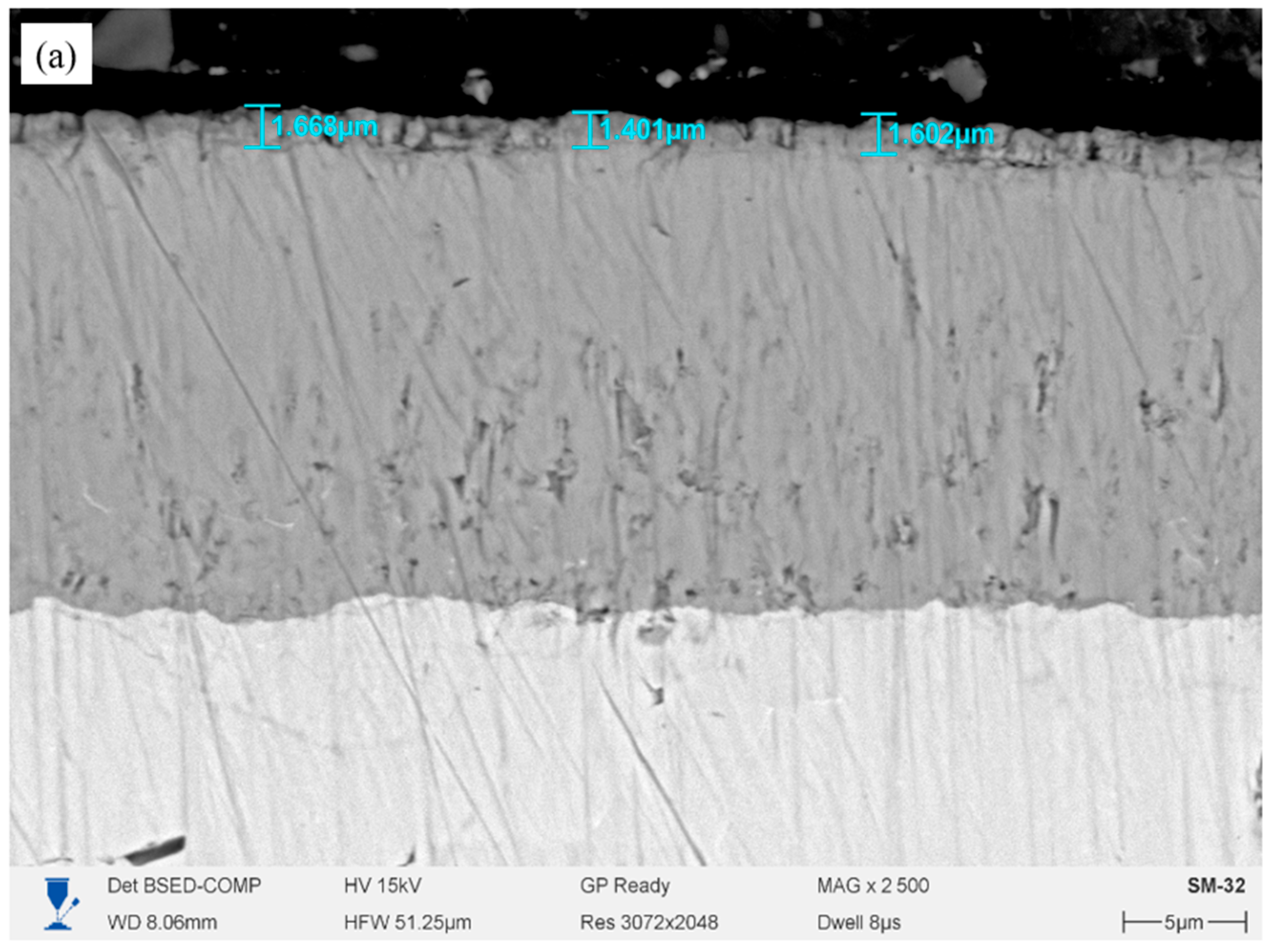

Figure 1 shows the cross-sections of Cr/CrN coatings deposited by magnetron sputtering on an E110 alloy substrate with different numbers of layers, before high-temperature steam oxidation (HTSO) testing. All coatings form a tight, continuous contact with the substrate without cracks, pores, or signs of delamination. The interlayer boundaries are smooth and clearly defined, and the light and dark bands correspond to alternating Cr and CrN sublayers. The single-layer coating (

Figure 1a) exhibits a uniform, dense structure without pronounced layered alternation. The total coating thickness is approximately 1.15–1.20 μm. The interface between the coating and the substrate is clearly defined, and the structure is uniform across the thickness. The two-layer coating (

Figure 1b) exhibits a distinct architecture consisting of a lower metallic Cr sublayer and an upper nitride CrN layer. The overall thickness is approximately 1.4 μm, with the top layer being approximately 0.9 μm thick and the Cr sublayer being approximately 0.4–0.5 μm. The coating adheres tightly to the substrate, and the layer structure is uniform, without pores or defects. In the four-layer coating (

Figure 1c), alternating Cr/CrN layers of uniform thickness are clearly visible. The overall thickness reaches approximately 2.7 μm, with the thickness of individual layers varying within the range of 0.46–1.07 μm. The structure is dense and uniform, without through defects. The six-layer coating (

Figure 1d) demonstrates the most developed multilayer architecture with regularly alternating Cr and CrN sublayers 0.4–1.0 μm thick. The overall coating thickness is approximately 4.18 μm. The microstructure is dense, the boundaries between the layers are clearly visible, and there are no pores.

Next, the phase composition of the coatings with different numbers of layers was studied before high-temperature steam oxidation (HTSO) testing.

Figure 2 shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the original E110 (Zr-1Nb) substrate and the Cr/CrN coatings produced by magnetron sputtering with different numbers of layers.

All coatings exhibit diffraction peaks corresponding to the Cr (BCC), CrN (cubic, Fm-3m), and ε-Cr2N (hexagonal, P312) phases, as well as reflections of metallic zirconium (Zr) on the substrate side. With increasing layer count, an increase in the intensity of the CrN peaks and a decrease in the intensity of the Cr2N reflections are observed, indicating more complete nitridation processes and stabilization of the cubic CrN phase in the multilayer coatings. Four- and six-layer samples typically developed a more uniform nanocrystalline structure, as evidenced by a decrease in peak width and an increase in peak intensity.

The samples were then subjected to high-temperature steam oxidation (HTSO) testing. The change in sample weight before and after HTSO testing was determined by direct weighing. Before weighing, the samples were pre-dried at 120 °C for 1 h to remove residual moisture and volatile products. Each sample was weighed three times before and after HTSO testing, after which the average weight was calculated.

The results of the change in sample weight before and after high-temperature steam oxidation testing are shown in

Table 1.

The obtained data show that the greatest weight change is observed for the uncoated E110 alloy, which is due to active oxidation of its surface. The application of CrN coatings and multilayer Cr/CrN systems significantly reduces the weight change (to +0.119–0.299 g), indicating improved oxide resistance. However, for the six-layer coating, a slight increase in Δm (+0.241 g) is observed, likely due to partial oxidation of the interlayer regions, which does not affect the integrity of the coating but does result in a slight weight gain.

Thermal exposure resulted in changes in their phase composition, as shown in the X-ray diffraction patterns (

Figure 3).

Figure 3 shows the diffractograms of the initial sample made of the E110 alloy (Zr-1Nb) and Cr/CrN coatings with different multilayer architectures (1-, 2-, 4-, and 6-layer) after testing for high-temperature steam oxidation at 1100 °C.

The analysis shows a significant change in the phase state of the surface depending on the number of coating layers, which reflects differences in the thermal stability and protective mechanisms of multilayer structures.

The diffractogram of the initial sample shows that the sample is characterized by a typical phase structure represented by tetragonal (t-ZrO

2) and monoclinic (m-ZrO

2) modifications of zirconium oxide, which are formed as a result of surface oxidation of the alloy under the influence of atmospheric oxygen. The presence of two polymorphic modifications is explained by the partial thermal transformation of the tetragonal structure into a monoclinic one during cooling after thermomechanical treatment. The absence of metallic Zr peaks indicates complete oxidation of the surface layer and the formation of a continuous oxide film several micrometers thick. After high-temperature vapor oxidation, the single-layer CrN coating is completely oxidized to form the corundum phase Cr

2O

3, with no CrN reflections. The formation of the corundum phase alone confirms that high-temperature vapor exposure caused complete decomposition of chromium nitride according to the reaction:

As a result, a structurally dense Cr2O3 oxide layer was formed, exhibiting high thermodynamic stability. In addition to chromium oxides, the X-ray diffraction pattern shows weak peaks corresponding to the tetragonal (t-ZrO2) and monoclinic (m-ZrO2) modifications of zirconium oxide. Their appearance is associated with partial oxidation of the E110 alloy substrate through microdefects in the coating and local areas of discontinuity in the oxide layer. The joint presence of Cr2O3, m-ZrO2, and t-ZrO2 indicates the formation of a composite oxide structure on the surface of the sample, where the outer layer is represented by a structurally dense Cr2O3 film, and near the substrate there are zones of zirconium oxides arising from limited oxygen diffusion through the coating. The results obtained indicate the complete decomposition of the nitride layer and the formation of a structurally dense but not completely sealed protective oxide coating that performs a protective function. However, the presence of weak ZrO2 peaks indicates the insufficient barrier efficiency of such a single-layer system.

In the case of a two-layer coating, thermal exposure results in the formation of a multiphase oxide structure consisting mainly of the Cr

2O

3 oxide phase, as well as traces of zirconium oxides (m-ZrO

2 and t-ZrO

2) formed due to limited oxygen diffusion to the substrate. The diffractogram shows intense peaks corresponding to Cr

2O

3 (corundum structure, space group R-3c), with characteristic reflections (104), (110), (113), (024), (116), (214), and (300) located in the regions 2θ ≈ 33.6°, 36.2°, 54.8°, 63.0°, 65.0°, and 69.1°. Among them, the most intense is the (110) reflection, which indicates the presence of a preferential orientation of Cr

2O

3 crystallites along this plane. The formation of the oxide structure is explained by the partial oxidation of the upper CrN nitride layer and the Cr metal sublayer, occurring according to the reactions:

The preferred orientation of Cr

2O

3 crystallites along the (110) plane is due to the directed growth of oxide grains during coating cooling after spraying. The formation of the Cr

2O

3 phase occurs from metastable CrO

x oxide compounds under thermal influence, and the (110) orientation is the most thermodynamically stable for a corundum-like structure. The proposed chemical transformations (1) and (2), describing the sequential oxidation of chromium nitride, are consistent with previously published data on the behavior of Cr and CrN coatings exposed to high temperatures in a vapor or oxidizing environment. According to literature sources [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24], at temperatures above 900–1000 °C, the phase evolution of CrN can proceed according to the scheme: CrN → Cr

2N → Cr

2O

3 + N

2, which is caused by the gradual release of nitrogen and the oxidation of chromium with the formation of stable oxide Cr

2O

3. These results confirm the thermodynamic validity of the proposed reactions and their correspondence to experimentally observed processes in Cr/CrN systems during high-temperature steam oxidation.

The presence of weak m-ZrO2 and t-ZrO2 peaks indicates limited oxidation of the substrate, which is significantly less than in the case of a single-layer coating. The formation of a stable Cr2O3 phase indicates high thermodynamic stability of the coating under HTSO conditions and ensures the formation of a structurally dense passive film, which plays a key role in protecting the E110 substrate from intense oxidation. The four-layer Cr/CrN coating is characterized by the formation of a predominantly Cr2O3 oxide phase with a corundum structure, accompanied by weak reflections of Cr2N and Cr. The presence of these phases indicates partial oxidation of the upper layers while maintaining the internal multilayer architecture. This indicates that oxygen diffusion into the coating was limited and that the oxidation process was completed mainly in the upper part of the multilayer structure. The appearance of diffraction reflections of the ε-Cr2N phase in a 4-layer coating is associated with incomplete nitridation of individual sublayers during sequential deposition. Weak m-ZrO2 and t-ZrO2 peaks confirm limited substrate oxidation. The presence of Cr(110) (~44.4°) and Cr(211) (~74.2°) confirms that some areas of the Cr metal layer remained largely unchanged. This indicates high stability of the interlayer distribution and the effectiveness of alternating nitride and metal layers in preventing through-oxidation.

The six-layer coatings demonstrate that the multilayer coating architecture provides the most stable phase state and the highest thermal stability among the samples studied. The diffractogram is dominated by intense peaks corresponding to the Cr2O3 phase (corundum structure, space group R-3c), indicating the predominance of a well-ordered oxide structure with preferential crystallite orientation. The presence of multiple high-intensity Cr2O3 reflections indicates the formation of a dense and continuous protective oxide film that prevents further oxygen penetration. In addition to the dominant oxide, weak reflections of CrN (111) (~37.5°) and (220) (~63.4°) remain, indicating partial preservation of the original nitride phase in the inner layers of the coating. The retention of the CrN phase after thermal treatment indicates limited oxygen diffusion into the structure and confirms the effective protective role of the external oxide barrier. The Cr2N phase is retained only in small quantities, primarily in the transition zones between individual layers, and does not significantly affect the overall phase composition of the coating. A decrease in the intensity of its diffraction peaks indicates increased uniformity of nitrogen distribution and more complete formation of the cubic CrN phase (Fm-3m). Weak Cr (200) (~44.4°) peaks are also observed, indicating the preservation of individual metal layers that have not undergone complete oxidation. The absence of ZrO2 reflections indicates effective insulation of the substrate from the oxidizing environment. Thus, the six-layer coating demonstrates the most effective phase state, in which the upper part of the structure is represented by a stable Cr2O3 phase, and the lower layers retain a combination of CrN and Cr, ensuring mechanical integrity and thermal protection.

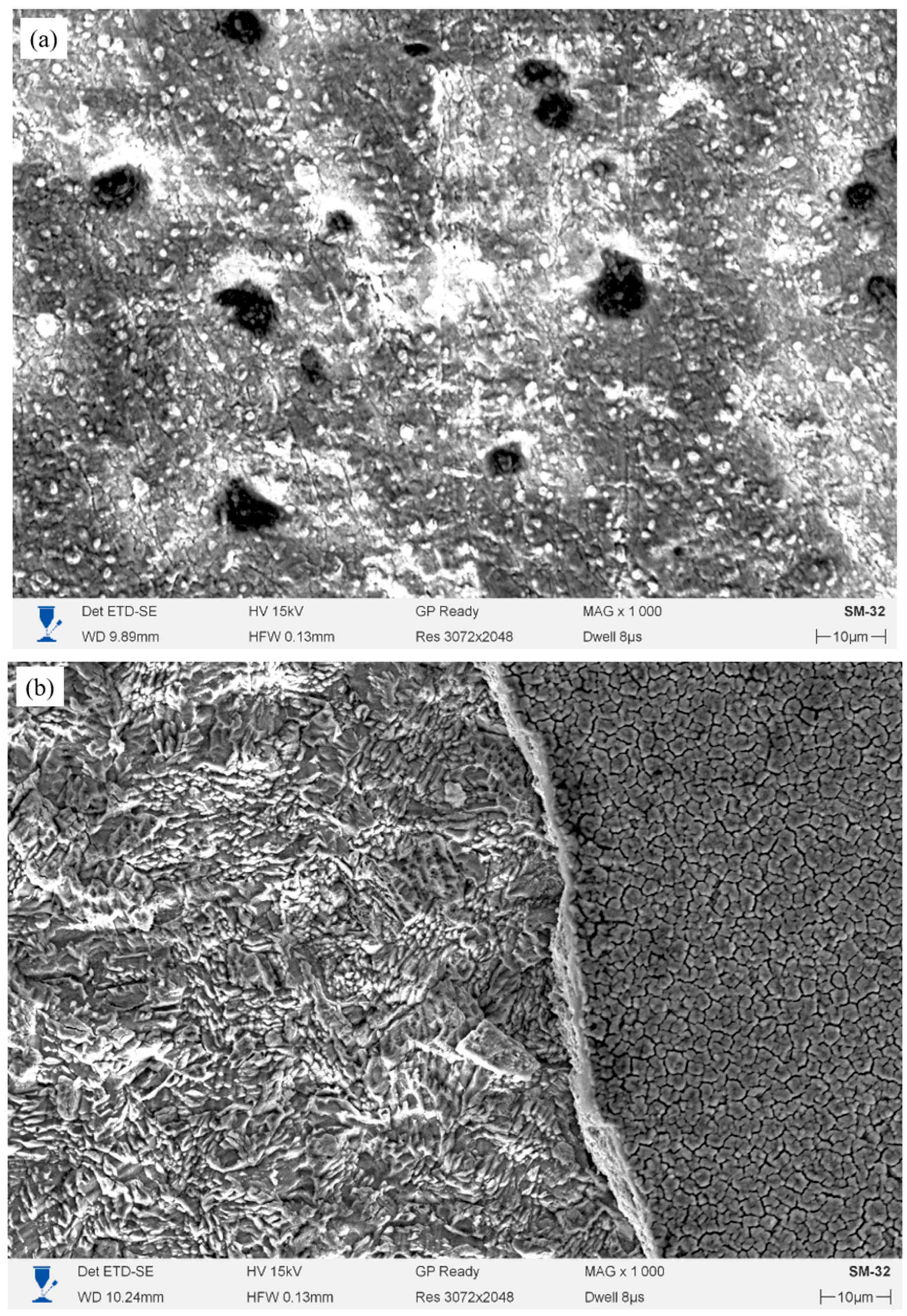

Figure 4a–e shows the morphological features of the surface of the initial E110 alloy sample, as well as single-layer and multilayer Cr/CrN coatings after testing for resistance to high-temperature steam oxidation at 1100 °C for 2 h.

The surface of the initial zirconium alloy (

Figure 4a) is characterized by pronounced roughness and the presence of numerous depressions and pores of various shapes and sizes. The dark areas correspond to zones of intense oxidation and local destruction of the oxide layer, where corrosion products have peeled off or flaked off. The light areas, on the contrary, represent areas of a denser and more stable oxide layer, presumably consisting of ZrO

2. The observed network of microcracks was formed as a result of thermal stresses arising from differences in the coefficients of thermal expansion between the substrate and the forming oxide film. Taken together, this indicates low thermal stability of the material without a protective coating and intense oxidation processes when exposed to water vapor at 1100 °C. The single-layer CrN coating partially protects the substrate, as evidenced by the zone of partial coating delamination from the Zr-1Nb alloy observed in

Figure 4b. The left side of the image corresponds to a Zr-rich substrate, while the right side corresponds to a coating characterized by elevated Cr and O contents. The difference in microstructure on either side of the crack indicates the boundary between the coating and the substrate and confirms partial coating delamination with localized oxidation of the surface layer to Cr

2O

3. The transition zone is clearly defined, indicating a reliable interface between the coating and the base material. Further, on the surface of the two-layer coating (

Figure 4c), a relatively smooth morphology is observed with a single delamination line at the boundary between the layers. The number of cracks is significantly lower than in the single-layer coating. This indicates that the introduction of a Cr metal sublayer improves thermoelastic compatibility and adhesion, reducing the likelihood of cracking during thermal cycling. However, individual defects (a single diagonally oriented thermal crack) indicate that the two-layer structure only partially provides long-term protection. The surface of the four-layer coating (

Figure 4d) exhibits a morphology that differs from the other samples.

To clarify their nature, additional EDS analysis was conducted.

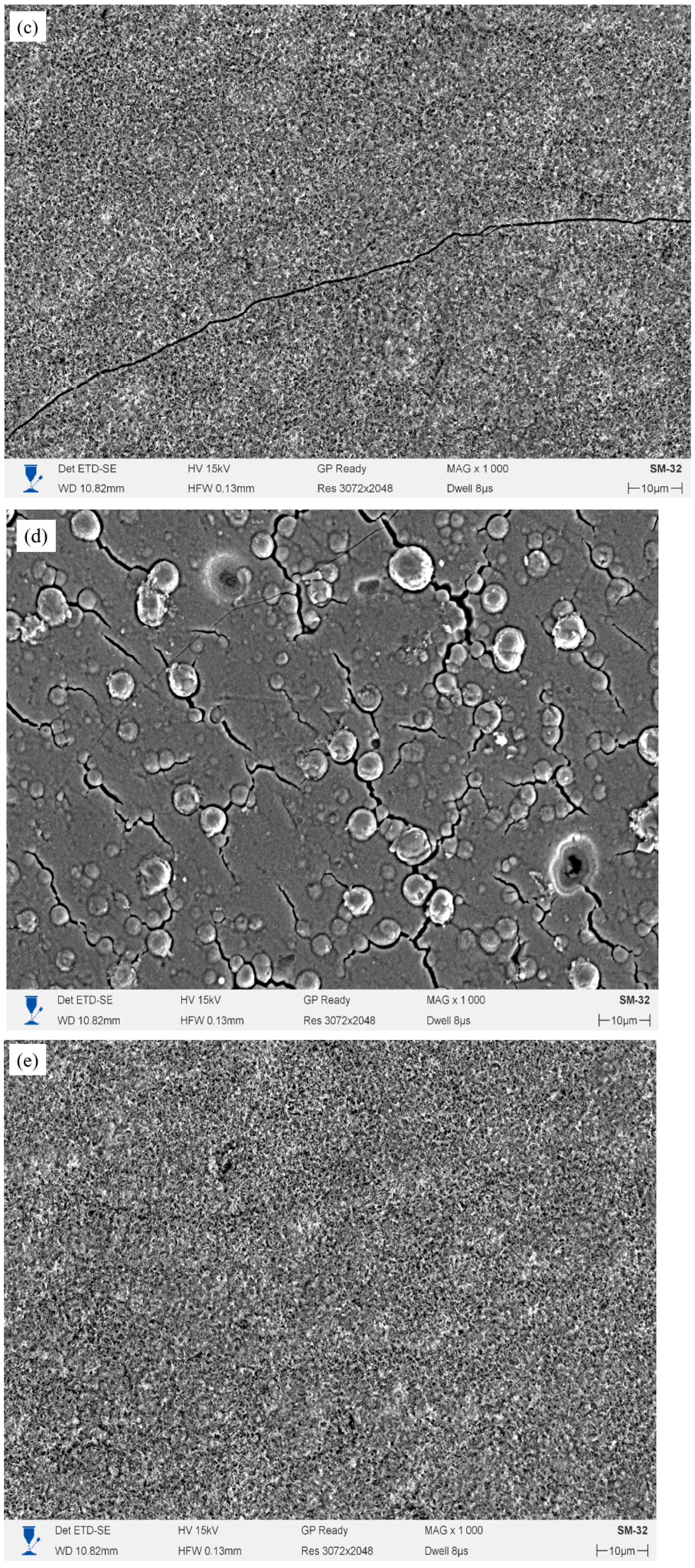

Figure 5 shows the surface mapping results of the four-layer coating after HTSO.

The observed rounded objects represent swellings of the surface oxide layer of Cr2O3, partially exposed in places, and therefore appear as dark pores/craters in the SEM images. EDS mapping shows elevated O content along the rims of these objects with low N content, which is consistent with the model of localized gas accumulation (O2, N2, H2) under the oxide film during HTSO and its subsequent swelling and rupture.

Cracks are observed between the bubble-like areas, caused by thermal stresses and local expansion of the oxide phase. At the same time, the coating retains its overall integrity: no continuous destruction or delamination is observed. Finally, the surface of the six-layer coating (

Figure 4e) is characterized by the densest and most uniform structure. No microcracks or pores were found. The coating has a fine-grained, uniform morphology, which indicates the formation of a stable and continuous oxide film, consisting mainly of Cr

2O

3. This structure ensures the integrity of the coating and indicates its high thermal stability and strong adhesion to the substrate after high-temperature steam oxidation (HTSO) testing.

To establish the relationship between surface morphology and the structural integrity of the coatings, their cross-sections were examined.

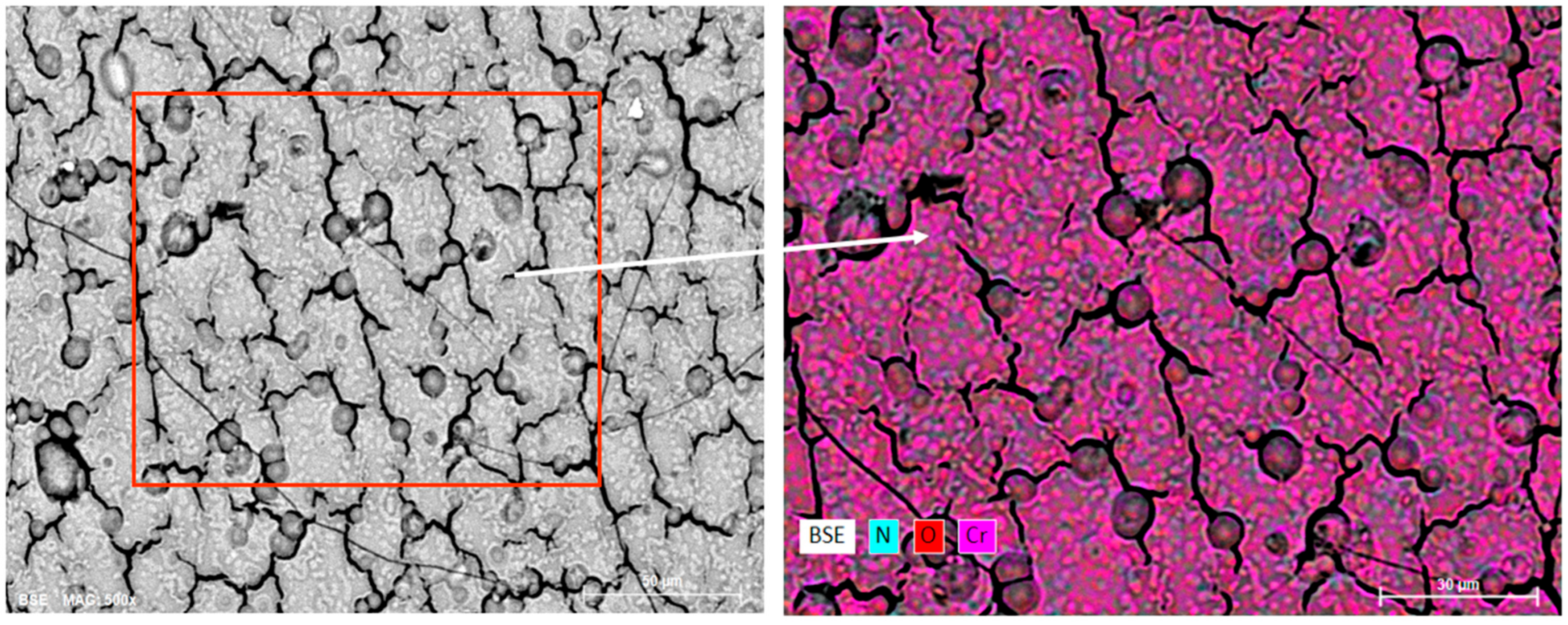

Figure 6 shows the microstructures of the cross-sections of Cr/CrN coatings after high-temperature steam oxidation (HTSO) testing at 1100 °C.

The images show: (a) single-layer CrN coating; (b) 2-layer Cr/CrN; (c) 4-layer Cr/CrN; (d) 6-layer Cr/CrN coating. The measured total coating thicknesses are approximately 1.6 ± 0.23 μm, 2.85 ± 0.32 μm, 5.8 ± 0.36 μm, and 9.62 ± 0.23 μm, respectively. After exposure to high-temperature water vapor, the overall integrity of the coatings is maintained, and a clear distinction is observed between the coating and the E110 alloy substrate. However, in multilayer systems, with an increase in the number of layers, partial blurring of the interlayer boundaries is observed due to diffusion and oxidation, which indicates thermal interaction between the Cr and CrN sublayers.

Figure 7 further presents the mapping results (a, b, c, d, e) performed on the coating cross-sections, as well as the element distribution along the selected analysis line (a.1, b.1, c.1, d.1, e.1). The resulting EDS maps allow us to visualize the spatial distribution of the main elements (Cr, N, Zr, etc.) and evaluate the degree of their interdiffusion between the coating layers and the substrate after high-temperature steam oxidation testing.

The presented micrographs and elemental distribution maps obtained by EDS clearly show the boundary between the E110 alloy substrate and the deposited coatings. On the uncoated sample (

Figure 7a), significant oxygen enrichment is observed near the surface of the E110 alloy substrate after testing, indicating the formation of a continuous ZrO

2 oxide film. The elemental distribution (

Figure 7(a.1)) shows a high Zr signal across the thickness, while the oxygen gradually increases from the inner layers to the surface. For the single-layer CrN coating (

Figure 7b) after HTSO, the formation of a surface oxide layer consisting predominantly of Cr

2O

3 is observed. The elemental distribution profile (

Figure 7(b.1)) shows an increase in the O concentration and a decrease in N in the upper zone of the coating, which corresponds to partial oxidation of chromium nitride. The coating-substrate interface is clearly defined, and Zr diffusion into the coating is absent. However, oxygen enrichment is observed in the near-surface zone of the substrate, indicating the formation of a ZrO2 oxide layer. The two-layer Cr/CrN coating (

Figure 7c) exhibits a uniform distribution of Cr and N across the coating thickness, with a distinct oxygen-enriched zone near the surface. The linear profile (

Figure 7(c.1)) confirms the presence of a diffusion barrier at the Cr–CrN interface, which limits the penetration of O and Zr. The structure retains a layered morphology, which contributes to increased thermal stability. The four-layer Cr/CrN architecture (

Figure 7d) exhibits a more uniform distribution of elements and a decrease in the O signal intensity compared to the two-layer version. The profile (

Figure 7(d.1)) shows that Cr and N are uniformly distributed, and Zr does not exhibit noticeable diffusion from the substrate. The presence of additional interfaces helps inhibit oxygen interpenetration, forming a stable protective structure. The six-layer Cr/CrN coating (

Figure 7e) maintains clear layer separation and high coating density after HTSO. The oxygen zone is limited to the upper surface layer, indicating the formation of a thin passive oxide film of Cr

2O

3. According to the linear profile (

Figure 7(e.1)), Cr and N are distributed stably, while Zr maintains a sharp transition at the substrate-coating interface. This structure ensures superior thermal stability and minimal diffusion of elements between the substrate and coating. Thus, the results of EDS mapping and linear analysis confirm the high thermal stability of multilayer Cr/CrN coatings and the effectiveness of their barrier properties when exposed to saturated water vapor at 1100 °C.

Comparison of the structural and phase characteristics showed that multilayer Cr/CrN coatings retain high thermal stability after exposure to water vapor at 1100 °C. Chromium nitride oxidizes to form a stable oxide Cr

2O

3 according to the reaction: 2CrN + 1.5O

2 → Cr

2O

3 + N

2 ↑. The Cr

2O

3 phase has a lower density (ρ ≈ 5.2 g/cm

3) compared to CrN (ρ ≈ 6.0 g/cm

3), which causes volume expansion (~10–15%) and a visual thickening of the upper zone [

25]. The actual thickness of the metallic nitride layer remains virtually unchanged. The resulting Cr

2O

3 layer functions as a diffusion barrier, preventing the penetration of oxygen and zirconium. In multilayer systems, residual Cr and CrN phases are retained, whereas in single- and two-layer coatings, complete conversion to Cr

2O

3 is observed. To investigate the resistance of various coatings to high-temperature steam oxidation, the evolution of single- and multilayer CrN and (CrN/Cr)ₙ systems after HTSO at 1100 °C for 2 h was assessed. The interpretation of the results was compared with the oxidation model schematically presented in

Figure 8.

When exposed to saturated water vapor on an uncoated Zr-1Nb substrate, intense oxidation of the zirconium occurs, forming a thick, porous, and cracked ZrO2 layer. Deep oxygen saturation of the base metal is observed, accompanied by a significant increase in mass and pronounced surface degradation. In the case of a single-layer CrN coating, the protective capacity is insufficient. The thin CrN layer completely or almost completely transforms into loose Cr2O3, in which defects and diffusion channels form. Through these defects, oxygen and water vapor freely reach the substrate, causing intensive growth of ZrO2 beneath the Cr2O3. The barrier function of the coating is lost in the early stages of testing. In the two-layer (Cr/CrN)2 system, the top layer of the coating also oxidizes to Cr2O3, but the combined thickness and number of interfaces remain insufficient to effectively suppress oxygen diffusion. The inner layers are partially preserved, but localized formation of ZrO2 at the interface with the substrate indicates a breakdown of the protective barrier. This structure provides only moderate resistance to HTSO. In the four-layer (Cr/CrN)4 coating, a dense, continuous Cr2O3 layer forms, significantly reducing the penetration of oxygen and water vapor. The inner Cr/CrN sublayers are partially oxidized but retain a pronounced multilayer morphology and integrity, providing significantly higher resistance compared to single- and two-layer versions. Finally, in the six-layer (Cr/CrN)6 structure, the maximum number of Cr/CrN interfaces forms the most effective diffusion barrier. After HTSO, a clearly defined multilayer structure is maintained, the upper Cr2O3 layer remains dense and stable, and the formation of ZrO2 is virtually absent. This coating demonstrates the highest resistance and provides almost complete protection of the substrate from vapor oxidation.