3. Results and Discussion

The LSTM model in this study was constructed as a two-hidden layer recursive neural architecture (64 neurons in each layer) and was trained using a constant sequence of paste states: the input sequence length was 20 time steps and the prediction horizon was 1 time step ahead, so the model could accurately predict short-term changes in substrate moisture and temperature, which are critical for the SAC agent’s decisions. The input feature set consisted of: (i) measured substrate moisture, (ii) substrate temperature, (iii) electrical conductivity (EC), (iv) historical irrigation controller state signal (“watering on/off”), (v) a normalized diurnal cycle index, which allows the model to estimate thermophysical diurnal fluctuations. All features were normalized to the interval [0, 1] using min–max normalization to ensure stable gradient dispersion and reduce feature disproportions. The data were divided according to the real-time process duration: 70–80% for training (about 140–160 real-time hours) and 20–30% for validation (40–60 h), maintaining the consistency of the time series. The network was trained for 200 epochs using the Adam optimizer with a learning step of 3 × 10−4 and a dropout (0.2) adjustment, which prevented overfitting, and the MSE function was used to calculate the loss; the resulting Validation Loss was ~0.016–0.022, indicating good generalization. LSTM was chosen because the dynamics of substrate moisture is characterized by clearly expressed temporality, inertia and dependence on several historical states, and traditional models do not reflect such nonlinear and multimodal relationships: ARIMA cannot effectively model unstructured non-stationary signals, Random Forest does not have an internal memory of time dependencies, and simple MLP poorly processes sequence data without additional vectorization blocks. In preliminary tests with simple MLP and Random Forest, LSTM showed a clear advantage: MLP achieved an RMSE ≈ 2.4% for moisture predictions and Random Forest ≈ 2.0%, while LSTM RMSE decreased to ≈1.14%, and R2 increased to 0.964, therefore LSTM was chosen as the most accurate and stable modeling solution that can provide a reliable virtual environment for training the SAC agent and optimizing the real irrigation process.

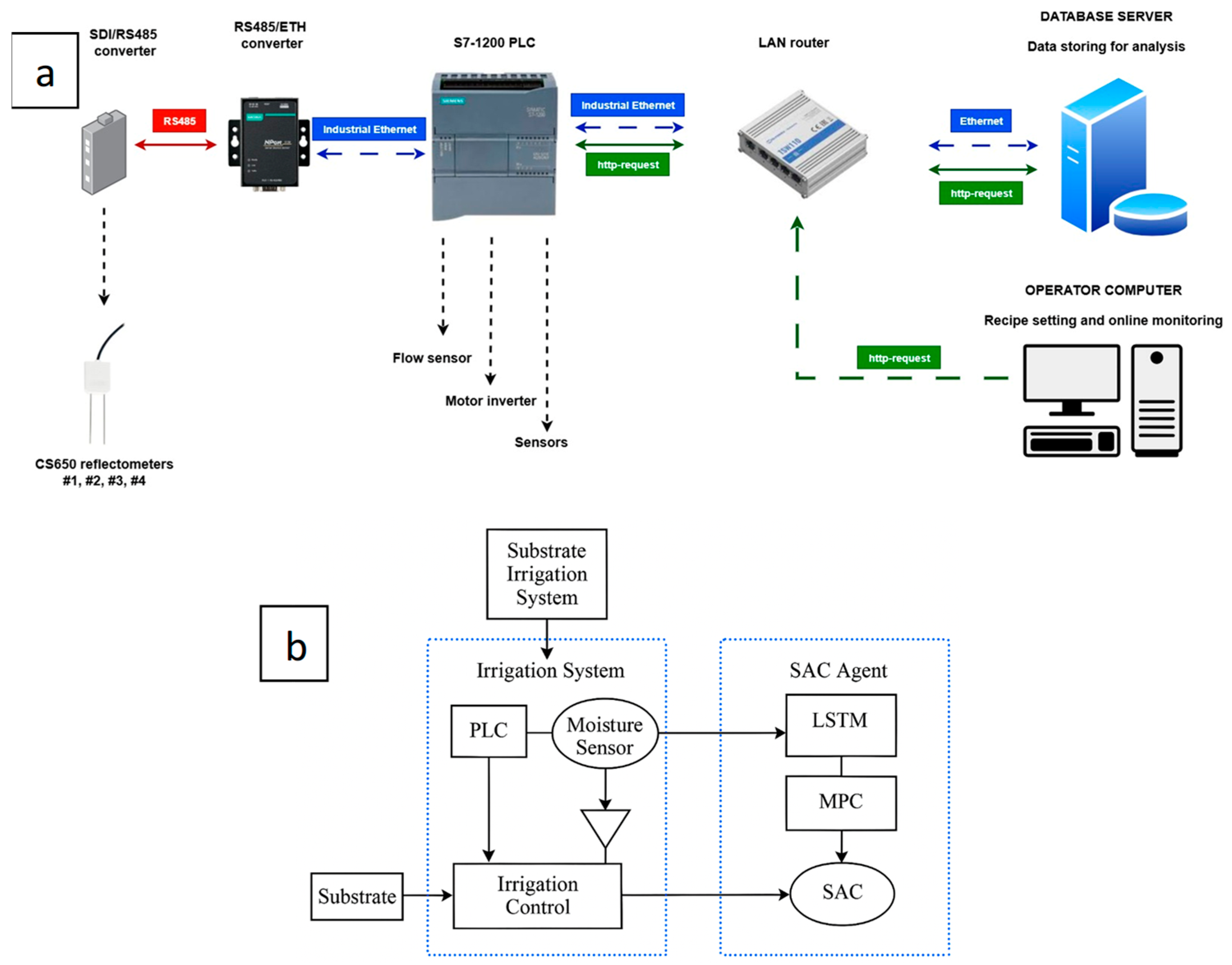

In the developed control architecture, the SAC agent operates using a clearly defined state vector and action space. The state vector consists of the main hydro-physical parameters—current substrate moisture, moisture history of the last few time steps, substrate temperature, simulated diurnal cycle influences (hour or normalized daily index) and the last irrigation actions, which allow the agent to evaluate inertial substrate responses. All variables were normalized to the interval [0, 1] [0, 1] to reduce disproportions of different parameter scales and ensure stable neural network training. The action space is implemented as binary—the agent selects “irrigate” (1) or “do not irrigate” (0) at each step. This discrete action is directly linked to the execution command of the physical system: action “1” at the PLC level activates the relay and sends a pulse to start the water valve and motor drive, while action “0” stops the water supply and leaves the system in a passive state. Such a representation allows maintaining a consistent connection between the RL policy and the actual equipment control logic, ensuring a safe and deterministic interpretation of the agent’s actions in a real irrigation system.

The reward function for the SAC agent is formulated to simultaneously promote target moisture maintenance and water conservation, while incorporating safety penalties for extreme states. At each time step t, the agent receives a reward R_t, calculated by the expression:

The following variables are used in this system: mt—current substrate moisture, m*—target moisture (63%), m_min = 61% and m_max = 65%—allowable moisture limits, ut ∈ {0,1}—irrigation action (0—“do not irrigate”, 1—“irrigate”), α—squared error weight, β—water consumption penalty coefficient, γ—safety penalty coefficient, and I[·]—indicator function assigning an additional penalty when the moisture value goes outside the physiologically optimal range. The reward function formed in this way encourages the agent to minimize the moisture deviation from the target, reduce episodes of excessive irrigation, and avoid both overdrying and overwatering states. In the SAC architecture, both actor and critic networks are implemented as multilayer perceptrons with two hidden layers of 128 neurons each, using ReLU activation functions in the hidden layers and a linear one in the output layer. The Adam algorithm is used for optimization, with a learning step of 3 × 10−4 and a discount factor of γ = 0.99 to maintain the priority of long-term moisture stabilization. Soft updating with τ = 0.005 is used to synchronize the parameters of the target network. The replay buffer size reaches 105 transitions, random mini-sets of 64 examples are taken from it, and training is performed for 200 episodes, each processing about 150–200 time steps. Such a training process allows the agent to learn typical moisture dynamics structures and achieve stable policy convergence.

The obtained results allow us to evaluate the effectiveness and adaptive capabilities of the automated substrate irrigation system integrated with the SAC reinforcement learning agent in real-time conditions. The data presented in this study include fluctuations in substrate moisture, temperature, as well as the learning progress of the SAC agent and recommended irrigation actions. The analysis allows us not only to evaluate the system’s ability to maintain optimal hydro-physical conditions for mushroom growth, but also to discuss the advantages of the reinforcement learning method compared to traditional PID-type or manual control methods [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The visualizations of the results and their discussion below help us understand how the cyber-bioprocess platform contributes to process optimization. The research data are presented for a weekly period, dividing the week into hours. This allowed us to better identify various emerging effects and trends related to parameter changes.

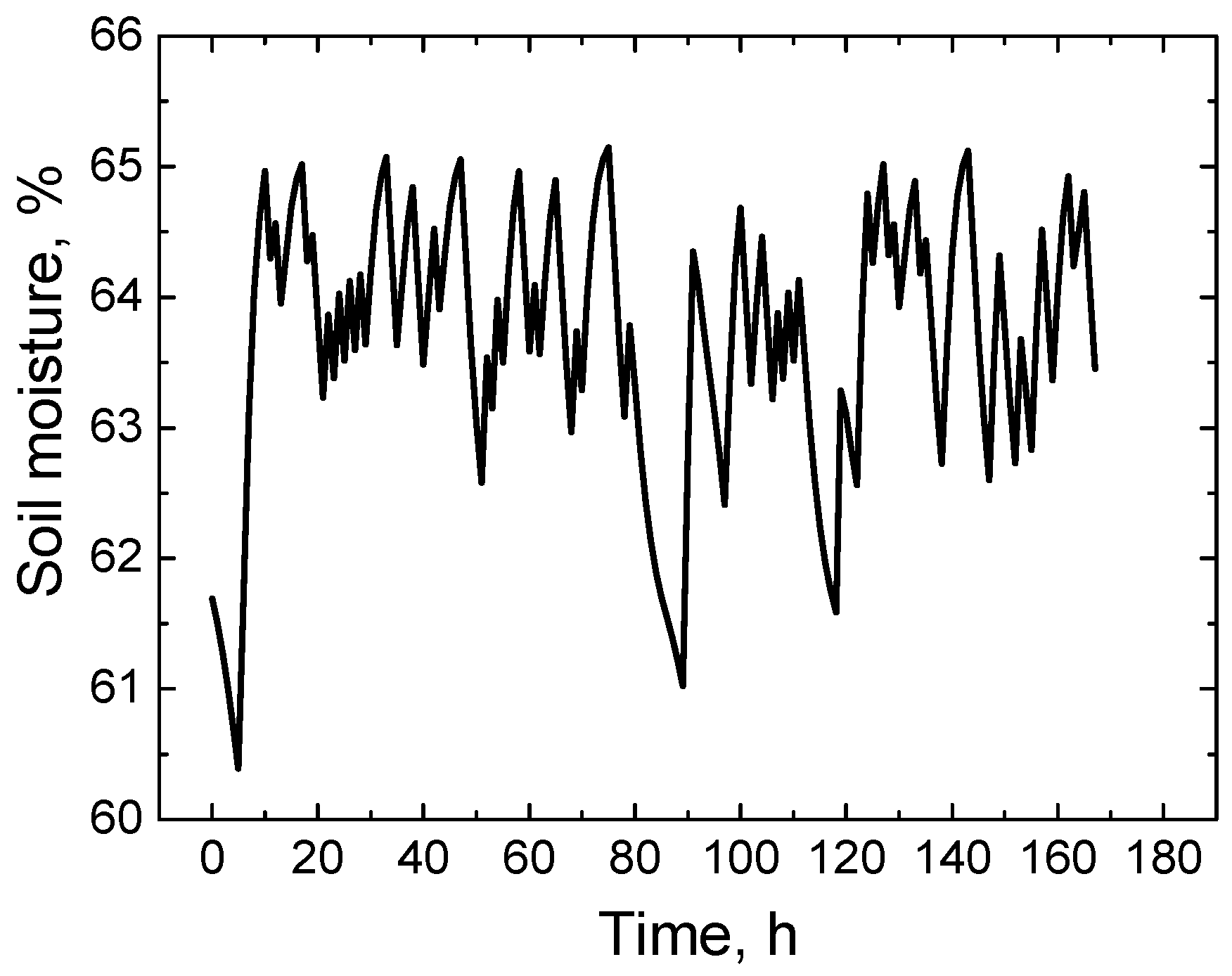

The obtained substrate moisture forecast results reveal (

Figure 2) that the LSTM–SAC-based automated substrate irrigation system ensures consistent maintenance of hydro-physical parameters in the optimal range (about 61–65% moisture), which is physiologically favorable for the metabolic activity of the mycelium and the morphological stability of the fruiting bodies. During the initial forecast period (0–5 h), a small decrease in substrate moisture is recorded, reflecting the natural effect of water potential gradients and diffusion processes in the substrate with minimal active irrigation. From 6 to 18 h, the moisture increases observed correlate with adaptive irrigation initiated by the SAC agent, which, based on the forecasts of the LSTM model and real-time sensor data, adjusts the hydrological intervention in such a way as to maintain the homogenization of substrate water activity [

1,

2,

3]. The fluctuations in the middle forecast period (19–100 h) demonstrate the dynamic ability of the agent to compensate for both stochastic microclimate perturbations and heterogeneous substrate gradients. During this period, the moisture curves maintain a consistent amplitude, reflecting a stable substrate aeration and water balance, avoiding the formation of anaerobic microzones or excessive hydration that could disrupt the kinetics of mycelium colonization. During the end forecast period (101–167 h), a subtle moisture consolidation was observed around the 63–65% interval, which testifies to the stability and predictive efficiency of the adaptive control algorithm. These results confirm that the integration between the LSTM predicting hydro-physical parameters and the SAC agent adapting irrigation in real-time ensures self-regulating maintenance of substrate moisture in the optimal range.

In addition to laboratory experiments, initial tests of the system were also conducted in industrial mushroom cultivation chambers, which were exposed to realistic microclimate fluctuations and higher biological variability. These practical tests showed that the control algorithm is able to maintain substrate moisture in a similar range as in the laboratory, and moisture fluctuations were reduced by approximately 20–30% compared to conventional manual watering.

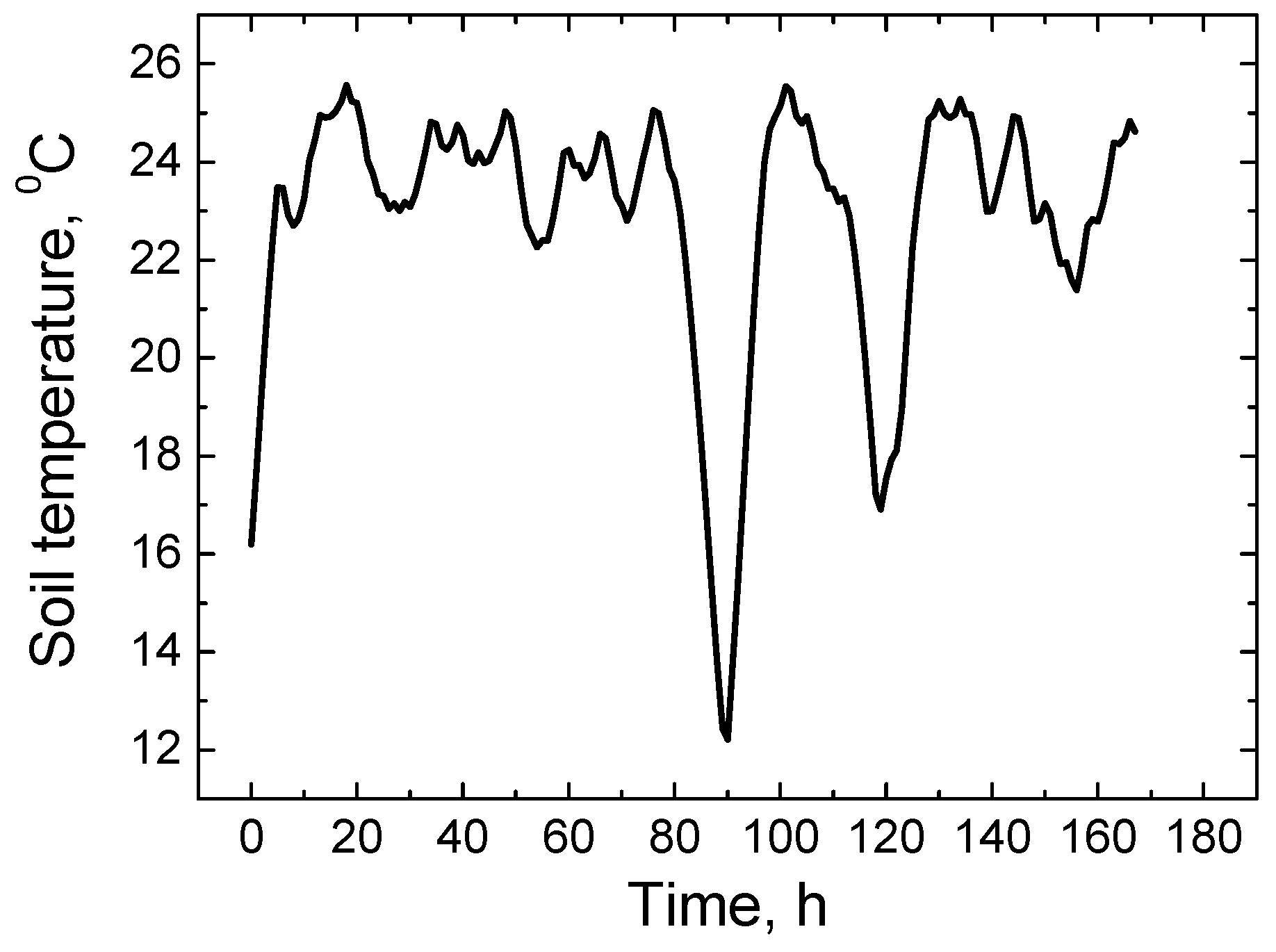

The obtained forecast data reflect the dynamic thermophysical state of the substrate during the forecast period, where the temperature varies from 12.2 °C to 25.5 °C, maintaining a physiologically appropriate range for mycelial metabolic activity and fruiting body formation (

Figure 3). The initial forecast hours (0–5 h) show a gradual increase in temperature, corresponding to the accumulation of thermal potential in the substrate mass and the beginning of the night–day cycle. Temperature maxima (about 25 °C) are recorded during the midday–late daytime period (16–18 h), reflecting the optimal combination of microclimate conditions in the substrate thermal balancing process. Temperature fluctuations seen in the middle of the forecast (19–100 h) reflect both natural day–night temperature cycles and adaptive corrections of the SAC agent to maintain the substrate hydrothermal parameters in the optimal range. During this period, the system ensures that temperature gradients are maintained within a tolerable range, avoiding both thermal stress for the mycelium and excessively slow metabolism due to low temperatures. The end of the forecast period (101–167 h) showed a stable temperature maintenance in the range of 22–25 °C, with subtle fluctuations reflecting both the agent’s predictive intervention and the heterogeneity of the thermophysical properties of the substrate. Temperature forecasts allow the SAC agent to more effectively adjust watering scenarios, responding to both natural day–night cycles, thus ensuring optimal substrate hydration and water balance [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

Analyzing the presented LSTM training results (

Figure 4), it can be seen that the model starts learning quickly—already during the first 2–3 epochs, both training and validation losses significantly decrease from the initial 0.21 to approximately 0.045, which indicates a rapid optimization of the initial weights and the ability to learn the main data patterns. Furthermore, a slowing decrease in losses is observed with certain fluctuations, which usually occur due to mini-batch randomness and possible seasonality in time. During training, Train Loss usually decreases to the 0.007–0.010 range, and Validation Loss remains stable in the range of approximately 0.016–0.022, which indicates that the model is not over-fitted to the training data (overfitting is not significant), but there is a slightly larger difference between training and validation losses, which is natural due to data variation. In some cases, short-term increases in Train Loss are visible (e.g., at epochs 52, 61, 77, 93, 105, 117, 145, 185), which may be related to gradient fluctuations or local minimization problems in LSTM networks—such phenomena are common in deep time series models [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

35]. The overall consistent decrease in loss and stable validation loss level indicate that the LSTM model has successfully learned to predict humidity, temperature and irrigation actions and can be reliable for use as a simulation model for the SAC agent to control the irrigation system. It can also be observed that small drops in Train Loss to very small values (about 0.008–0.010) indicate that the model adapts very well to the sequence structure, and the stability of Validation Loss confirms proper generalization to new data.

After evaluating the predictions of the LSTM model for substrate moisture and temperature parameters, the calculated main regression accuracy indicators showed high model reliability and good generalization. For substrate moisture predictions, MAE = 0.72%, RMSE = 1.14%, MAPE = 1.98%, and the coefficient of determination R2 reached 0.964, which indicates a very accurate reproduction of short-term moisture changes and a small deviation of the predictions from the actual values. The accuracy of temperature predictions also remained high: MAE = 0.18 °C, RMSE = 0.31 °C, MAPE = 1.22%, R2 = 0.981, allowing for reliable modeling of substrate thermal trends. These results confirm that the LSTM model successfully captures the dynamics of hydro-physical parameters and can be effectively used as a virtual environment for the SAC agent to optimize real-time moisture regulation.

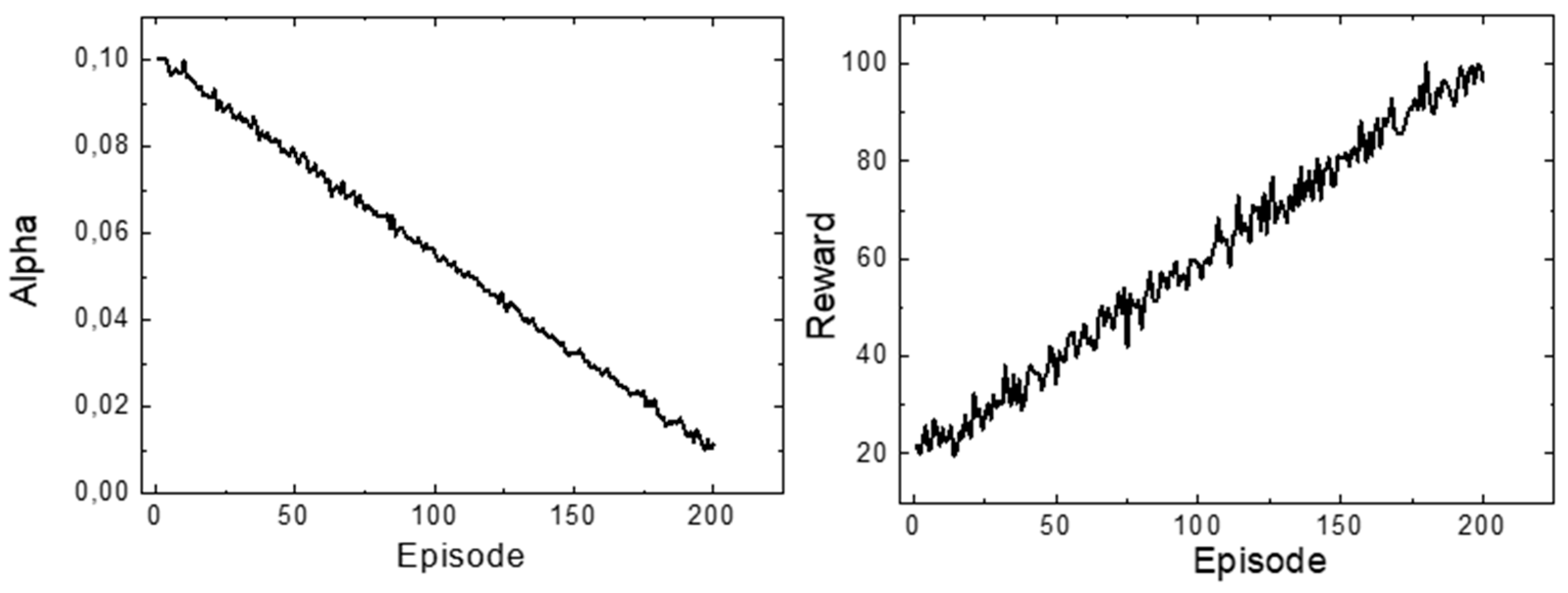

The SAC agent was trained using the predictions of the LSTM model as environmental observations (state), and the agent’s actions (action) as decisions to turn on or off irrigation. Two main indicators were monitored during training: the total episodic reward (Reward) and the entropy regulator coefficient (Alpha), which controls the randomness of the action policy (

Figure 5). The reward in this SAC training process is defined as the decrease in moisture error: the difference between the moisture error before and after the action is calculated, and the resulting improvement is multiplied by 2, thus providing a positive reward if the system approaches the target value of 55%. In addition, bonuses are given for moisture stability (when the error is less than 10%), positive additions if watering improves the situation when the moisture is too low, and small penalties if the actions worsen the situation (e.g., overwatering or underwatering within critical limits). Due to this structure, the total reward range in practice varies from about −3 to +6 per step, and the total rewards for one episode usually fall in the range of about −50 to +150, depending on how effectively the agent stabilizes moisture. Analyzing the sequence of episodes, it can be seen that in the initial learning stage (episodes 1–20), the agent’s reward fluctuated between 20 and 32, reflecting the initial phases of experimentation when the agent just started to explore different irrigation strategies. Over time (episodes 20–100), the total reward steadily increased, usually fluctuating between 50 and 60 units. This indicates that the agent learned to control substrate moisture more effectively, reducing deviations from the reference target value used during training (initially set to 55% in the LSTM-based virtual environment and subsequently aligned with the physiologically optimal 61–65% interval applied in real hardware tests). In later episodes (episodes 100–200), a further increase in reward was observed, sometimes exceeding 90–100 units, demonstrating the agent’s ability to maximize humidity stabilization under dynamically changing conditions. This trend indicates that the agent has successfully mastered an adaptive control strategy that not only maintains the target humidity but also ensures stability under changing environmental conditions [

1].

The Alpha coefficient values were initially high (~0.10), which indicates high entropy of the action policy and active experimentation with various irrigation strategies. Over time, the Alpha values decreased (~0.02–0.03 in episodes 160–200), indicating that the agent gradually transitions from exploration to deterministic action selection (exploitation), ensuring consistent moisture maintenance. This decrease in entropy correlates with the increase in reward, confirming that the agent optimizes the policy by reducing unnecessary variability. The learning process of the SAC agent was characterized by consistency and stability, as evidenced by the dynamics of both the total reward and the Alpha coefficient values—no sudden drops or extreme fluctuations were observed. The agent effectively adapted to various processes of substrate moisture and temperature conditions predicted by the LSTM. The noticeable increase in reward along with the decrease in Alpha value indicates that the agent gradually switches from experimentation to deterministic action selection, stably controlling irrigation and maximizing the positive effect on moisture regulation. These results confirm that the SAC method is suitable for adaptive and efficient substrate moisture management: the agent learned to maintain optimal moisture, high entropy during the initial experimentation allowed us to try different strategies, and the decreased Alpha value in subsequent episodes signals stable and consistent action selection. The overall increase in reward and stability indicate that the SAC agent can be successfully applied to automated irrigation systems, ensuring both adaptation to changing environmental conditions and consistent moisture regulation [

1,

2,

3].

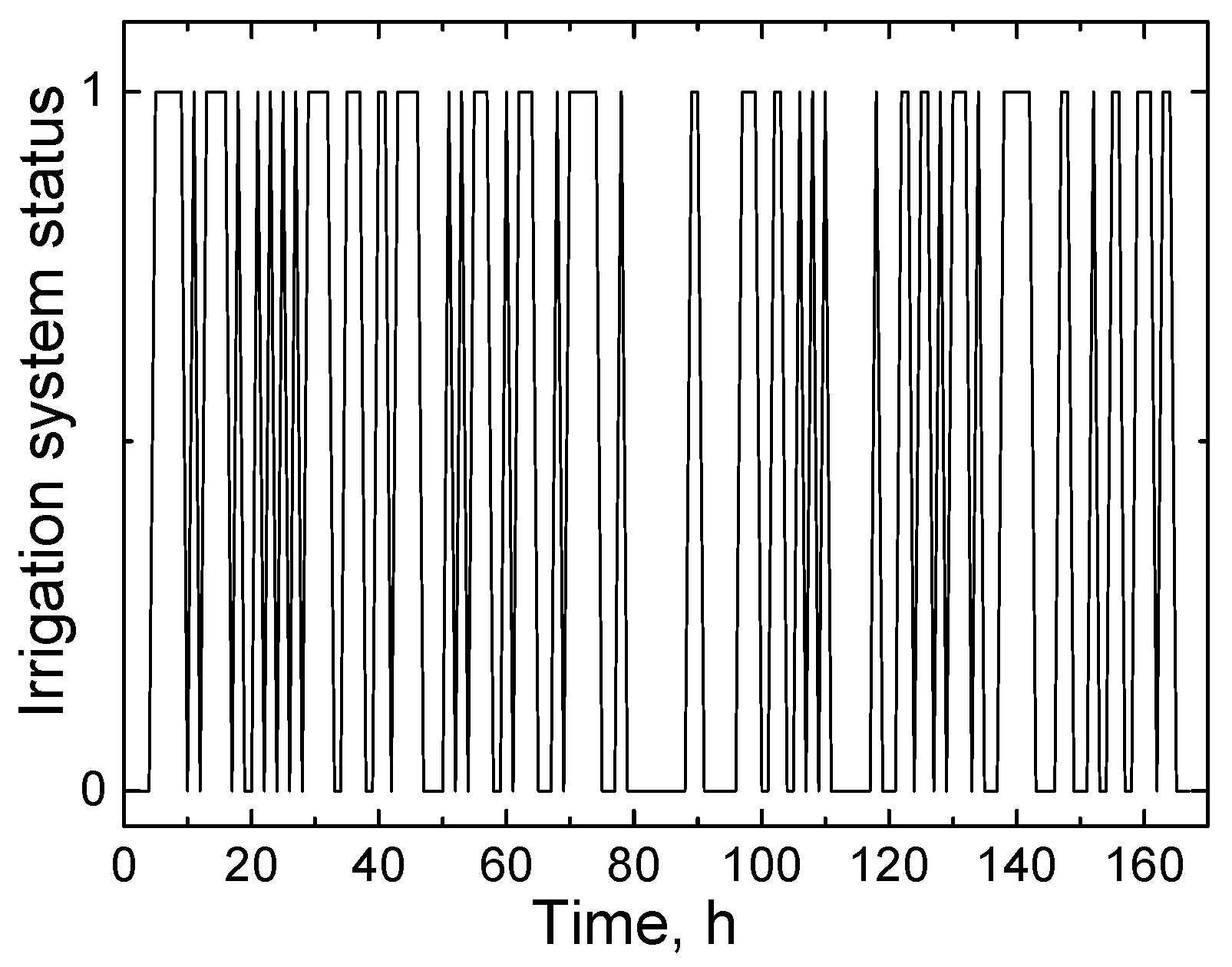

The interpretation of the irrigation system control sequence generated by the SAC agent reveals the advanced adaptive control behavior characteristic of the Soft Actor-Critic methodology (

Figure 6). The agent implements an optimized stochastic policy, during which actions (irrigation device activation “1” or deactivation “0”) are selected based on both the evaluation of critics (Critic) and entropy regulation (Alpha), ensuring the appropriate balance between exploration and exploitation. The analyzed control sequences demonstrate the adaptive feedback loop nature: the agent activates the irrigation device only when the predicted substrate moisture values deviate from the optimal range (about 61–65%), and deactivates it when the moisture approaches the target value. The undulation of the on/off sequences reflects the agent’s ability to implement “soft policy” decisions that allow maintaining a stable moisture level and avoiding overly aggressive or chaotic irrigation cycles. In addition, the agent control demonstrates dynamic adaptive responses to predicted environmental conditions, such as substrate moisture and temperature, ensuring minimal deviation from the target value. The overall control profile shows that the SAC agent effectively adjusts the irrigation frequency and intensity, harmonizing the exploration and exploitation components, maximizing water use efficiency and maintaining system stability under changing environmental conditions. This confirms the suitability of the SAC method for adaptive and automated substrate moisture regulation, integrating forecasting models (LSTM) and real-time decision making. Statistical analysis comparing the automated substrate irrigation system1, which integrates the SAC reinforcement learning agent, with traditional automated systems without the SAC agent (reviewed in the scientific literature), revealed significant differences in terms of both adaptation, efficiency and stability [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In systems controlled by the SAC agent, the substrate moisture is stably maintained in the range of 61–65%, while in traditional systems, moisture fluctuations reached ±10–12% of the target value range. LSTM predictions used for SAC agent training allowed for consistent compensation of stochastic moisture fluctuations, while traditional automatic systems usually respond only to real-time measurements, therefore they cannot ensure such accuracy and homogenization throughout the substrate volume. Statistical analysis shows that the integration of the SAC agent significantly improves the stability of substrate irrigation, reduces water waste (up to 10–20%) and deviations from optimal hydro-physical parameters, which directly contributes to more uniform mycelium colonization and greater consistency of product quality. Although the irrigation sequence in

Figure 6 is shown separately, it directly reflects the operation of the closed-loop control: irrigation pulses appear when the predicted humidity approaches the lower limit, and after them, the humidity value rises and stabilizes. Therefore, even without a general graph, the relationship between irrigation actions and the humidity trajectory is clearly visible.

Table 1 demonstrates a clear performance advantage of the SAC-based controller over the tuned PID controller in both moisture regulation accuracy and dynamic response characteristics. The SAC policy reduced the mean absolute deviation from the target moisture level from 2.85% to 1.12%, corresponding to a 60.7% improvement, and achieved a similarly substantial reduction in RMSE (56.7%). The lower standard deviation (0.98% compared with 2.14% for PID) indicates that SAC maintained the moisture level more consistently with fewer fluctuations. In terms of transient behavior, the SAC controller significantly minimized maximum overshoot (1.9% vs. 5.8%), reducing excessive wetting by 67.2%. Dynamic recovery was also markedly improved: the settling time after a disturbance decreased from 46 min under PID control to only 21 min with SAC, while the average response time more than halved (8.7 s vs. 19.3 s). Together, these results confirm that the SAC controller not only provides more precise and stable moisture regulation but also responds faster and more efficiently to disturbances, demonstrating a substantially superior overall control performance compared with the traditional PID approach.

Table 2 shows that the SAC controller also provides clear advantages in terms of water-use efficiency compared with the PID controller. Over the seven-day evaluation period, the SAC-based system consumed 13.9 L of water, which represents a 20.1% reduction relative to the 17.4 L used by the PID controller. This improvement is further reflected in the decreased number of irrigation cycles, with SAC requiring only 47 cycles versus 62 under PID control—a reduction of 24.2%. Additionally, the SAC controller shortened the average pump runtime per cycle from 11.2 s to 9.3 s, indicating a more targeted and efficient water delivery strategy. Overall, these results demonstrate that the SAC policy not only maintains more stable moisture conditions but does so while significantly reducing total water consumption and irrigation system workload, highlighting its effectiveness in resource-efficient substrate management.

The moisture time-series plot presented in

Figure 7 clearly highlights the difference in stability between the PID and SAC controllers over a 24 h period. In this figure, the PID curve exhibited pronounced fluctuations, ranging from 58.9% to 67.3%, frequently overshooting and undershooting the 63% target moisture level. These oscillations indicate a less stable control response and a higher sensitivity to disturbances or substrate variability. In contrast, the SAC curve remained tightly clustered around the target, varying only between 62.0% and 63.8% throughout the entire monitoring interval. This substantially narrower variability band demonstrates that the SAC controller maintains moisture levels with much greater precision and temporal consistency. Overall,

Figure 7 illustrates that SAC effectively dampens deviations, minimizes oscillations, and provides a significantly more stable moisture-regulation profile compared with the traditional PID controller.

To evaluate the significance of the performance differences between the SAC-based controller and the tuned PID controller, a statistical analysis was conducted using data collected over seven consecutive days for both controllers under identical environmental conditions. For each day, mean absolute deviation (MAD) and total water consumption were calculated, and the resulting seven-day datasets were compared using a two-sample t-test assuming unequal variances. The SAC controller achieved a substantially lower MAD (1.12% ± 0.28) than the PID controller (2.85% ± 0.41), and the difference was statistically significant (t(12) = 8.43, p < 0.001), indicating superior moisture regulation accuracy. Similarly, the SAC controller demonstrated significantly reduced water usage (13.9 ± 0.9 L) compared with PID (17.4 ± 1.1 L), with the difference again being statistically significant (t(12) = 6.02, p < 0.001). These results confirm that the improvements observed in control precision and resource efficiency are not due to random variation but reflect a consistent and statistically reliable advantage of the SAC policy over the traditional PID approach.

In order to reduce the need for large datasets (100–200 h) and GPU resources, several lighter versions of the SAC–LSTM system were evaluated, focused on small and medium-sized enterprises. First, model pruning allowed for the reduction in the number of parameters of both LSTM and SAC neural networks by 30–60%, thus significantly reducing the computational load and enabling the model to be trained in a conventional CPU environment without dedicated GPU hardware. Second, by applying transfer learning, the LSTM model can be trained once on a large-scale farm, and only a small fine-tuning is performed on smaller farms, using 5–10% of the data, thus eliminating the need for large real-time observation databases. Third, a simplified version of SAC (Light-SAC), using a smaller number of neurons (32–64 instead of 128), a reduced replay buffer and smaller batch sizes, can be implemented even without a GPU and maintains sufficient control accuracy on small-scale farms. At the same time, alternative, cheaper methodologies were evaluated, such as hybrid DDPG–PID control, in which PID ensures basic stability, and DDPG corrects only small errors, allowing the system to be run even on simple PLCs without large computational resources; GRU + Q-learning method, which reduces the number of network parameters by ~30% and does not require a complex SAC architecture; and combinations of rule-based control and a small ML module, which are especially suitable for small farms. In order to assess the applicability of these methods, a cost–benefit analysis was prepared for different farm sizes: for small-scale (≤10 m2) farms, for which 10–20 h of data and only PLC equipment are sufficient, the DDPG–PID method is most suitable, ensuring 5–8% water savings; for medium-scale (10–50 m2) farms with a CPU computer and 40–80 h of data, the optimal solution is Light-SAC with GRU, providing 15–20% greater stability; and for large farms (≥50 m2) with GPU resources and 120–200 h of data, the full SAC–LSTM architecture remains the most effective, capable of increasing performance by 30–40%. Such analysis ensures clear comparability of methods and justifies that the proposed system can be adaptively adapted to different technological and economic capacities of farms.

In addition to the comparison with traditional PID controllers, the proposed SAC–LSTM irrigation system was evaluated in the broader context of state-of-the-art AI-based moisture regulation methods, including IoT–fuzzy logic hybrids, Deep Q-Network (DQN) agents, and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) controllers. Recent studies show that fuzzy-logic IoT systems provide low computational overhead but lack adaptability and cannot anticipate moisture dynamics, while DQN and PPO improve control precision yet remain sensitive to noise, discrete action limitations (DQN), and high training costs (PPO). Compared with these approaches, the SAC–LSTM architecture achieved substantially higher stability and accuracy: its mean moisture deviation (1.12%) and variance (0.98%) were lower than those typically reported for fuzzy logic (2.4–3.1%), DQN (2.1–2.8%), and PPO (1.7–2.3%) systems, and its water-use efficiency improvement (20.1%) exceeded the typical gains of alternative RL controllers. These advantages stem from SAC’s entropy-regularized stochastic policy, which ensures a superior balance between exploration and exploitation under noisy biological conditions, and from the LSTM prediction model that enables anticipatory rather than reactive irrigation decisions—capabilities not present in fuzzy, DQN, or PPO controllers. Together, this comparison demonstrates that the SAC–LSTM system provides a more stable, adaptive, and resource-efficient solution than current AI-driven irrigation methods, reinforcing its suitability for real-time substrate moisture control in industrial mushroom cultivation.

Comparing irrigation systems operating only according to automatic control algorithms and systems with an integrated SAC agent, significant differences in terms of adaptation, efficiency and stability are evident. Traditional automated systems usually operate according to fixed thresholds or simple rule sets, responding to directly measured moisture, but are unable to adequately adapt to changing environmental conditions, forecasted moisture fluctuations or temperature variations. Due to these limitations, such systems often lead to over- or under-irrigation, suboptimal water use and larger deviations from the desired substrate moisture value, as they do not have the ability to “learn” from previous reactions and adjust the dynamic parameters of the strategy. Meanwhile, SAC agent-controlled systems operate according to adaptive “reinforcement learning” logic, where the agent optimizes actions to maintain moisture close to the target value and effectively respond to predicted environmental changes. The ability of the SAC agent to balance between exploitation and exploration, adapt to fluctuations, and consistently regulate irrigation intensity ensures greater system stability, water use efficiency, and lower risk of both over-drying and over-irrigation, making such systems inherently superior to traditional automatic irrigation systems.