Abstract

Background: The development of the curve of Spee (CoS) is influenced by skeletal morphology, orofacial growth, tooth eruption timing, mandibular relationships, overbite, and neuromuscular development. This systematic review aims to determine the most effective orthodontic methods in correcting the curve of Spee. Methods: The systematic review protocol was registered on the PROSPERO platform and conducted according to the Cochrane and PRISMA guidelines. For its development, a standardized search was performed across different databases (MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, Embase and Web of Science) and grey literature. The risk of bias was assessed using Faggion, Jr.’s guidelines for in vitro and in silico studies of dental materials, and the Rob-2 and ROBINS-1 tools for clinical studies. Results: The initial search found 748 studies, with 44 selected after full-text review. Of these, 22 were included in the quantitative analysis, assessing the effectiveness of braces (with or without extractions) and invisible aligners. Key methods for correcting the curve of Spee include various orthodontic archwires (nickel–titanium (NiTi), stainless steel, beta-titanium), continuous and segmented techniques, reverse curve archwires, aligners, and treatment modalities including extraction protocols. Most in vitro studies and randomized studies had a high risk of bias, and non-randomized studies showed moderate to high bias risk. Conclusions: The results suggest that conventional techniques, particularly non-extraction approaches, may be more effective than aligners in correcting the curve of Spee, although the available evidence remains limited.

1. Introduction

The search for aesthetic has become one of the main goals of orthodontic treatment, along with preserving the health of periodontal tissues, maintaining treatment stability and achieving a healthy occlusion. The occlusal curvature in the sagittal plane was labeled Spee’s curve in 1890 by the German anatomist Gran Von Spee [1,2,3,4,5]. Currently, in orthodontics, the CoS is determined by the arc of a curved plane tangent to the incisal edges of the central incisors and the vertices of the buccal cusps of the mandibular teeth, seen in a sagittal plane [2,3,5,6].

There is limited knowledge in the literature regarding the factors behind the development of this curve, and several factors have been speculated to influence the morphological arrangement of the teeth in the sagittal plane [3,7]. Some authors suggest tooth eruption, the growth of orofacial structures and the development of the neuromuscular system [2,3,8]. CoS is also influenced by craniofacial morphology, but to a lesser degree [2,3,6]. In addition to these factors, overjet, the height of the molar cusps, the quality and quantity of posterior occlusal contacts and the inclination of the temporomandibular joint have also been thought to be potential factors with influence over the CoS [7,9]. Comparing the different Angle classifications in terms of CoS depth, the curve depth was greater in the Class II division 1 malocclusion group, followed by Class II division 2, Class I and Class III malocclusions [6]. Whilst comparing the depth of the CoS with the divergence of the facial profile, Halimi et al. reported that there was no statistically significant difference between hypodivergent, normodivergent and hyperdivergent patients [7]. On the other hand, studies by Trouten et al. and Orthlieb have shown a deeper curve in hypodivergent patients [10,11]. It should be noted that pronounced CoS has often been observed in dental malocclusions with deep overbites [2,6].

The presence of a flat CoS is crucial for the efficiency of the masticatory system, since it has been suggested that the CoS has a biomechanical function in food processing and subsequently increases the efficiency of occlusal forces and the crushing/shearing ratio between the posterior teeth [2]. In addition, an increase in the depth of the CoS can cause occlusal interference, which can lead to pain, discomfort and damage to the tooth structure [4]. This can lead to the development of malocclusions, which impair phonation, chewing and oral hygiene, increasing the risk of periodontal disease and caries lesions. In addition to these risks, disorders of the temporomandibular joint can also arise due to excessive stress exerted on it [4]. Correcting CoS is therefore imperative to ensure balanced occlusal function [2,4]. Various orthodontic methods have been used to correct this curvature, from fixed to removable appliances, with or without orthognathic surgery [12,13]. The dental movements used for leveling may include intrusion of the anterior teeth, extrusion of the posterior teeth, proclination of the lower incisors or a combination of these movements [2,6,9,12,14,15,16]. The choice of treatment method depends on several factors, including the vertical dimension and incisal exposure at rest and when smiling [9,17].

The current scientific literature reflects an ongoing debate regarding the most effective method for leveling the CoS, with various orthodontic techniques described but no clear consensus on their comparative efficacy [2,4,6,9,18,19]. While the general aim of treatment is to achieve a level occlusal plane, the available evidence remains fragmented and, in many cases, inconclusive, particularly concerning treatment protocols, outcome measures, and long-term outcomes. Given the diversity of therapeutic approaches and the variability in reported results, it becomes essential to determine the most effective treatment. Accordingly, this study aims to qualitatively synthesize the existing evidence on orthodontic methods used to correct the Curve of Spee through a systematic review, and to quantitatively compare their effectiveness through a meta-analysis, when data homogeneity allows. This approach enhances the overall strength of the evidence and contributes to identifying the most effective strategies for clinical practice. In doing so, the present review addresses a relevant gap in the literature and aims to support evidence-based orthodontic decision-making.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

This review was carried out in accordance with the guidelines Cochrane and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. The protocol was registered into the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under the number CRD42024512212.

2.2. PICO Question

The PICO question (Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome) aims to answer the clinical question: ‘Which orthodontic methods are effective for correcting Spee’s curve?’ Specifically:

- Population (P): Patients undergoing orthodontic treatment presenting with an accentuated curve of Spee, as well as in vitro models simulating this condition.

- Intervention (I): Orthodontic techniques or mechanics aimed at leveling or correcting the curve of Spee.

- Comparison (C): Alternative orthodontic approaches or conventional treatment methods used to achieve curve correction.

- Outcome (O): Improvement or leveling of the curve of Spee, assessed through quantitative measures such as changes in curve depth or occlusal plane leveling.

2.3. Search Strategy

A standardized search was carried out in various databases by two reviewers independently (A.P. and I.F.), namely MEDLINE (through PubMed), Web of Science (all databases), Cochrane Library and EMBASE until 27 January 2025. In addition to these databases, a grey literature search was also carried out on the websites: HSRProj, OpenGrey Europe (https://opengrey.eu (accessed on 27 January 2025)) and ProQuest (https://www.proquest.com (accessed on 27 January 2025)). When appropriate, a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MesH) terms and keywords was used. The search formulas used in each database are presented in Table A1. No filters were used during the searches.

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

The defined inclusion criteria included randomized clinical trials and non-randomized controlled trials, retrospective and prospective cohort and case–control studies, cross-sectional studies, including in silico studies, and in vivo clinical studies involving patients undergoing orthodontic treatment to correct the CoS. Literature reviews, systematic reviews, case series studies, editorials, conference abstracts, book chapters, guidelines, protocols and opinion pieces were excluded. Studies that included patients diagnosed with systemic diseases and/or syndromes were also excluded.

2.5. Selection of Studies

Initially, two reviewers (A.P. and I.F.) independently analyzed the articles by title and abstract, based on the previously defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The articles that met the inclusion criteria were subjected to a full reading of the text by two independent reviewers. In cases of doubt at any of the selection stages, a third reviewer was consulted (F.V.). The software used for reference management was Rayyan (available at https://www.rayyan.ai; accessed on 15 March 2025).

2.6. Data Collection and Synthesis

The included studies were thoroughly analyzed and the following information was extracted by two independent reviewers (A.P. and I.F.): author and year of publication, study design (in vitro, in vivo, ex vivo or clinical), sample size, sample distribution by gender (where applicable), average patient age, orthodontic appliance, follow-up time, main results, primary outcomes, secondary outcomes and conclusions. In the event of disagreement on the information to be included, a third reviewer was consulted (F.V.). The results from the selected studies were presented in a combination of narrative and tabular formats, in accordance with the PICO question.

2.7. Analyzing the Risk of Bias

The methodological quality of the in vitro studies was assessed using the guidelines by Faggion, Jr. [20], The Cochrane Risk of Bias tools were used to carry out the qualitative assessment of the clinical studies (RoB-2 and ROBINS-I tools) [21,22]. The overall individual risk of bias of the studies was categorized into three categories: low -all domains assessed with low risk of bias; moderate–low or moderate risk of bias for all domains; high -at least one domain presents a serious risk of assessment bias. The articles were assessed by two independent reviewers (A.P. and I.F.) and, in the event of disagreement, a third reviewer (F.V.) was consulted.

2.8. Quantitative Data Analysis

The quantitative analysis of the data of clinical studies was carried out through meta-analysis using a random-effects model (DerSimonian–Laird method) in the Metafor software in R v4.1.2 [23]. The depth of the Curve of Spee was measured as the perpendicular distance from a reference plane—connecting the incisal edges of the central incisors and the distal cusp tips of the most posterior teeth—to the deepest cusp tip, averaged between the right and left sides. Differences in measurement protocols between studies were minimized by analyzing the within-study change from pre-to post-treatment.

Heterogeneity between the included studies was assessed using the I2 index with 95% confidence intervals and Cochran’s Q test. The I2 index indicates the proportion of the total variation between studies that is due to heterogeneity, while the Q test assesses whether the variability observed between studies is greater than that expected by chance. Absolute heterogeneity was quantified using τ2 with corresponding confidence intervals. The paired measures of each study were analyzed using the mean of within-subject differences (pre-post changes), calculated from paired measurements within each patient. Where correlation coefficients between pre-and post-treatment measurements were not reported in the original studies, we estimated them using established methods for before-after comparisons. For studies lacking reported correlations, it is noted that although sensitivity analyses across a range of assumed correlations can sometimes be informative, the limited number of studies in several comparisons makes such analyses unlikely to materially affect the results. Subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses were not performed due to the limited number of studies available for several comparisons (one of the meta-analyses included only 2 studies). The certainty of evidence was assessed using the GRADE methodology. To visualize the results, forest plots were generated illustrating the magnitude and direction of the effects for three types of treatment: conventional appliances, conventional appliances with extractions and invisible aligners.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

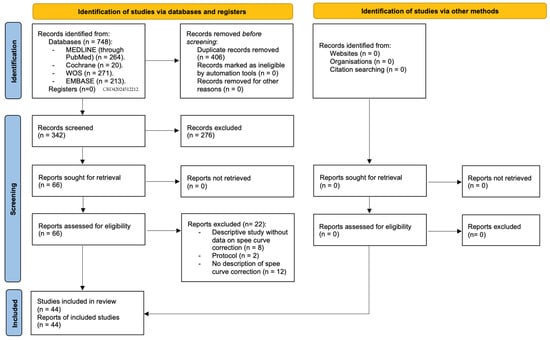

The initial search, carried out in the aforementioned databases, brought together 748 studies. After removing duplicates, 342 studies were selected for reading the title and abstract. Afterwards, all studies that did not fulfil the previously defined eligibility criteria were excluded, resulting in 66 studies for full reading. As 22 articles did not fulfil the inclusion criteria (Table A2), 44 were included in the qualitative analysis. The identification, screening and eligibility process are described in the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram.

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies Included

This systematic review included 6 in silico studies and 38 clinical trials. The characteristics and results of the in silico studies and clinical trials are shown in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. Table 3 summarizes the findings of clinical studies in general.

Table 1.

Summary of extrapolated data from included in vitro and in silico studies.

Table 2.

Summary of extrapolated data from included clinical trials.

Table 3.

Summary of findings.

The sample size in the clinical studies ranged from 10 to 168 subjects, with studies with approximately 30 to 40 subjects being the most common. The average age ranged from 11.6 to 40.7 years, predominantly adolescents. Most studies have a higher number of female subjects [9,26,31,32,33,34,37,43,45,46,47,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,58,59,60,62,65]. Some studies do not report average age or gender [36,42,64].

Follow-up in the clinical trials ranged from 1 year to 11 years. However, 25 studies did not report the follow-up period [9,14,24,26,27,29,31,35,36,37,38,39,40,43,44,47,48,51,53,54,55,56,58,59,61,63,65].

The main methods used to correct the CoS are conventional fixed appliances, dental extractions with fixed appliances and invisible aligners. The most used method is the orthodontic arch, varying in terms of material and section. The continuous arch technique is also the most widely used and has proved to be effective in CoS leveling [9,14,30,32,33,34,39,41,45,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,63,65]. This leveling occurs mainly by extrusion of the premolars and molars and by proclination and intrusion of the incisors.

With regard to the type of archwires used, the majority of studies report the use of nickel–titanium (NiTi), stainless steel and Beta-Titanium (TMA) orthodontic archwires using the continuous archwire technique and the segmented archwire technique, with/without the incorporation of reverse curve archwires [9,14,24,25,27,32,33,35,38,41,44,45,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,63,65].

When differentiating between fixed appliance systems, most studies employing continuous arch mechanics reported a greater degree of CoS reduction compared to segmented arch approaches, mainly through extrusion of posterior teeth and proclination of the lower incisors. Studies using segmented mechanics generally aimed for more controlled intrusion of anterior teeth and less unwanted proclination, but few directly compared the two techniques, resulting in limited comparative evidence. Regarding treatment with and without extractions, the available studies did not demonstrate consistent differences in the magnitude of CoS leveling. While extraction protocols theoretically allow for greater incisor retraction and vertical control, the included studies did not systematically evaluate these effects, and heterogeneity was substantial.

In the studies in which the correction method is invisible aligners, it is reported that the leveling prediction by the aligner software is not very accurate [43,49,51], and is even less accurate in adults [49]. When analyzing treatment with clear aligners, most studies reported that CoS leveling occurred predominantly through incisor intrusion, given that posterior tooth extrusion demonstrated lower accuracy and predictability. Consequently, the use of auxiliary mechanics is often recommended to optimize vertical control and treatment efficacy.

A comparison between the effectiveness of the continuous arch technique and aligners was carried out in only one study [9]. In this study, there were no statistically significant differences in the leveling of the CoS, with leveling occurring mostly through the intrusion of the lower incisors with the aligners and through the extrusion of the posterior teeth and proclination of the lower incisors using the continuous arch technique alone.

3.3. Summary of Quantitative Evidence

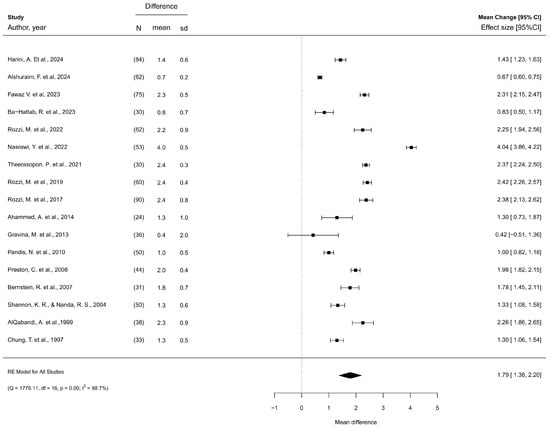

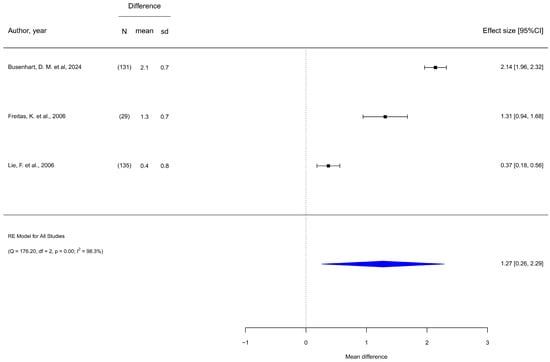

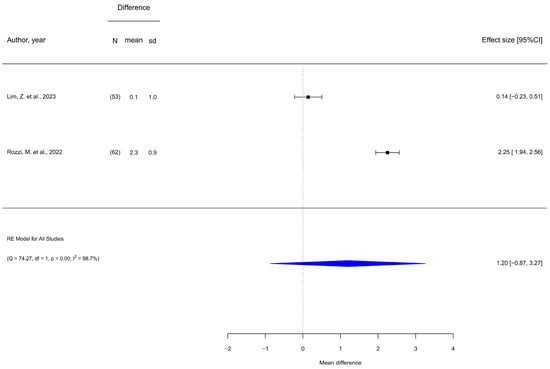

The aim of the present meta-analysis was to evaluate the effectiveness of different orthodontic treatment methods in correcting the CoS. The graphs comparing conventional appliances, conventional appliances with extractions and invisible aligners are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively. The results show that all the orthodontic methods analyzed are effective in correcting CoS, with variations in the magnitude and consistency of the effects observed.

Figure 2.

Effectiveness of conventional appliances [9,14,30,31,32,33,36,39,44,45,54,56,57,59,60,62,65].

Figure 3.

Effectiveness of conventional appliances in conjunction with dental extractions [34,41,50].

Figure 4.

Effectiveness of invisible aligners [9,51].

Regarding studies comparing conventional appliances (Figure 2), the effect size is 1.79 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 1.38 to 2.20, which indicates a significant positive difference. No evidence of publication bias was found. Heterogeneity was high, with τ2 = 0.729 [0.394–1.745] and I2 = 98.7% [97.7–99.5].

Regarding studies comparing conventional appliances in conjunction with dental extractions (Figure 3), the effect size is 1.27 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.26 to 2.29, which suggests a significant positive difference in the overall effect. It should be noted that the lower confidence interval is close to zero, which indicates a lower certainty in the combined estimate. Heterogeneity was also high (τ2 = 0.784 [0.204–30.953]; I2 = 98.3% [93.9–99.9]).

Regarding invisible aligners (Figure 4), the graph shows high variability among the included studies, and although there is a trend towards a positive difference, the overall results are not conclusive due to the wide confidence interval. Heterogeneity was substantial (τ2 = 2.199 [0.414–100.0]; I2 = 98.7% [93.2–99.9]).

According to the GRADE framework, the overall certainty of the evidence for this outcome was rated as very low (Table 4). The certainty of evidence for all three treatment modalities was assessed as very low. This was primarily due to very serious concerns about statistical inconsistency (I2 > 98% for all comparisons), serious to very serious risk of bias in the included studies, and serious to very serious imprecision due to small sample sizes. These findings indicate very limited confidence in the effect estimates, and further high-quality research is needed to establish the effects of these orthodontic interventions.

Table 4.

GRADE Evidence Profile.

3.4. Risk of Bias Analysis

Regarding in silico studies and in vitro, most studies presented a high risk of bias. This is mainly due to the absence of sample size determination, randomization and blinding in treatment allocation; blinding in outcome measurement; the description of statistical methods and failures in the provision of their protocols. Additionally, two studies did not detail the interventions in each group [26,29].

Concerning randomized controlled trials, all studies presented a high risk of bias. Studies classified as having a high risk of bias did not mention the randomization method. The domains with the highest risk of bias are effect of assignment to intervention and missing outcome data.

Regarding non-randomized clinical studies, thirteen studies presented a high risk of bias due to a lack of definition of the intervention classification [30,31,34,36,39,42,46,48,50,51,52,62,64], one for confounding factors [63], one for selection of participants [45] and two for deviations from intended interventions [43,51]. The remaining studies presented a moderate risk of bias, mainly due to participant selection [9,35,37,40,41,47,49,53,55,56,58,59,60].

4. Discussion

Correction of CoS is essential to achieve ideal occlusion and improve masticatory function. In the current literature, there is still debate about which orthodontic method is most effective for CoS leveling. Therefore, the objective of this systematic review was to summarize the existing orthodontic methods for CoS correction. Orthodontic treatments commonly use NiTi, stainless steel, and TMA archwires with various techniques, but there is no consensus on the best biomechanical approach for stable, long-term leveling [56]. The results of the present study have resulted in the verification of three of the evaluated orthodontic methods in the meta-analysis as effective in correcting CoS. Nonetheless, these findings should be interpreted with caution due to the overall low quality of the available evidence. The methodological quality of the included studies was limited, with randomized controlled trials presenting high risk of bias and non-randomized studies showing moderate to high risk. The most frequent methodological shortcomings included lack of randomization, inadequate blinding procedures, in-sufficient description of statistical methods, and poor reporting of intervention protocols. These limitations may have affected the internal validity and reliability of the findings. Moreover, in silico studies frequently failed to define sample size, apply proper randomization or blinding, or describe the interventions clearly, further reducing the strength of their conclusions. Such methodological weaknesses compromise the generalizability of the results and preclude strong clinical recommendations. Therefore, the conclusions presented should be viewed as indicative rather than definitive, reinforcing the urgent need for high-quality and well-designed randomized clinical trials. In addition to clinical outcomes, it is important to consider the cost-effectiveness and patient-centered aspects of the evaluated techniques, as these factors play an increasingly significant role in contemporary orthodontic decision-making and the overall quality of care.

Regarding the continuous or segmented arch technique, the present study revealed an effect size of 1.79. A study by Preston et al., which compared the two techniques, observed that both produced statistically significant reductions in CoS [57]. However, in the post-retention stage, with a follow-up of approximately four years, a statistically significant but clinically insignificant relapse was observed [57]. The continuous arch technique is the most described, varying in the studies in terms of material and arch section and frequently incorporating the reverse curve arch form. Leveling with this technique is mostly achieved by extrusion of the premolars and molars and by proclination and intrusion of the incisors [9,33,54,55,56,58,59,60]. This technique demonstrates effective leveling of CoS, however, with some degree of relapse observed in the post-retention period [9,33,41,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. In studies in which the correction method was invisible aligners, it is reported that the leveling prediction by Clincheck is not very accurate, and in the study by Kravitz et al., it was demonstrated that the accuracy is lower in adults compared to adolescents [49]. The extrusion movement of the posterior teeth is less accurate than the intrusion movement of the incisors [49]. According to Goh et al., to achieve the desired treatment objectives, an overcorrection of the CoS leveling should be prescribed in the treatment plan in ClinCheck and the addition of auxiliary methods such as attachments [43]. The recent systematic review by Boccuzzi et al. further supports these findings, indicating that ClinCheck tends to overestimate the clinical correction of deep bite due to the lack of standardized staging and biomechanical protocols, thus requiring planned overcorrections. Moreover, the application of posterior occlusal bite blocks and traditional attachments appears to have minimal influence on the success of open bite closure [66].

In a study by Rozzi et al., which compared the continuous arch technique with aligners, there were no statistically significant differences in the CoS leveling, which was effective in both groups [9]. This leveling occurred mainly due to the intrusion and proclination of the lower incisors [9]. In this sense, if one of the treatment objectives is the extrusion of the posterior teeth, the continuous arch technique is more advantageous than invisible aligners. Proclination of the lower incisors can be an undesirable effect of orthodontic treatment, since it can put the supporting tissues at risk, compromising aesthetics and stability [14]. A study by AlQabandi et al. compared the effects on the axial inclination of the lower incisors between rectangular and round arches and found no differences between the two arches [14]. Additionally, the study by Theerasopo et al. reported that the phased implementation of alignment followed by leveling is more advantageous in controlling incisor inclination [65].

The decision of the orthodontic method to be applied depends on the defined orthodontic objectives, since the CoS can be affected by several variables, namely, stage of dental eruption, timing of dental eruption, dental occlusion, craniofacial characteristics such as facial pattern, neuromuscular factors and parafunctional habits such as bruxism that can promote tooth wear [67]. Rozzi et al. reported that, in patients with low maxillary-mandibular angle, leveling occurred by vestibularization and intrusion of the lower incisors, while in patients with high maxillary-mandibular angle, leveling occurred through extrusion and verticalization of the posterior teeth [59,60]. A recent study by Alshuraim et al. found that there is no statistically significant difference between 2nd molar bonding and the amount of CoS reduction [31].

Several factors for the long-term stability of CoS correction have been highlighted in the literature, namely: amount of growth, patient age during treatment, muscle strength, neuromuscular adaptation and initial malocclusion [68]. Busenhart and collaborators concluded that the greater the amount of CoS correction, the greater the post-treatment relapse [34]. On the other hand, Lie reported that there is greater stability of the CoS after relatively large changes in the treatment of deep curves [50]. Furthermore, in the study by Preston et al., it was found that there is greater relapse when the treatment does not correct the CoS to a completely leveled curve [57]. Razdolsky et al. demonstrated that relative vertical movements can continue up to 21 months after the end of orthodontic treatment [69]. Therefore, it is crucial to maintain the CoS after the end of treatment with appropriate retention methods. The recurrence of CoS in orthodontic treatment with or without dental extractions remains a controversial topic in the scientific literature. The study by Shannon and Nanda reported no significant differences between the recurrence of CoS in the groups with or without extractions. The authors also reported that the use of fixed retainers instead of removable retainers is associated with a lower degree of recurrence [62]. However, in a study by Busenhart et al., it was established that premolar extractions may be associated with a lower degree of recurrence [34]. Among the 22 studies included in the quantitative synthesis, 11 did not report any follow-up, including all investigations assessing aligners, while follow-up in the remaining studies ranged from 1 month to 11 years. This variability may considerably affect the interpretation of treatment efficacy, as short-term post-treatment assessments may not accurately capture the long-term stability of curve of Spee correction. In particular, the lack of follow-up data for aligner studies precludes definitive conclusions regarding their durability and the potential for relapse in comparison with conventional orthodontic techniques. These observations highlight the necessity for future studies with standardized and adequately long follow-up periods to provide more robust evidence on the sustained effectiveness of different orthodontic interventions.

This systematic review has some limitations that may alter the interpretation of the results, including: (1) a few of the included studies had a small sample size and were not described in detail; (2) some included studies had a high risk of bias; (3) heterogeneity of the studies in terms of the CoS measuring method, both in the definition of the occlusal plane and in the selection of the teeth to be measured; (4) lack of information regarding clinical follow-up in some studies; (5) lack of detailed description of the orthodontic method used; (6) the included studies did not stratify samples by facial divergence, despite evidence that divergence may influence the depth of the Curve of Spee. According to the risk of bias analysis, some of the parameters analyzed with the highest risk of bias were flaws in the classification of the intervention, the randomization process, the blinding process and the definition of the statistical methods. The increased risk of bias affects the internal validity of the studies, making the results less reliable and applicable. Furthermore, it may over or underestimate the observed effects, leading to incorrect clinical or scientific decisions. These factors should be considered when interpreting the results of the present review. It is essential to carry out more clinical, controlled and randomized studies that report all the parameters described in this systematic review and that evaluate the effectiveness of the various orthodontic methods with similar protocols, so that an effective comparison can be made between them.

Future research should prioritize adequately powered randomized controlled trials with harmonized outcome definitions and standardized methods for measuring the Curve of Spee. Studies should include sufficient follow-up periods to assess stability and relapse and adopt comparable retention protocols to allow meaningful head-to-head comparisons between aligners and conventional fixed appliances. Such investigations would provide higher-quality evidence to guide clinical decision-making and enable more reliable evaluation of the relative effectiveness and long-term outcomes of different orthodontic interventions.

5. Conclusions

Despite the heterogeneity of the included studies, the available evidence indicates that CoS correction can be achieved using different methods, such as conventional appliances, conventional appliances combined with extractions and aligners. Although some findings suggest that conventional techniques appeared more effective than aligners, this observation is primarily based on limited direct comparative data and studies with moderate to high risk of bias, which reduces the certainty of these conclusions. Therefore, such conclusions should be interpreted with caution. The choice of method to use should be individualized, considering the patient’s diagnosis and treatment objectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: I.F. and F.V.; Data curation: M.P.R., F.C. and A.B.P.; Formal analysis: F.C. and C.M.M.; Investigation: A.L.P., R.T. and C.N.; Methodology: C.M.M. and I.F.; Project administration: A.B.P. and F.V.; Software: F.C. and C.N.; Supervision: I.F. and F.V.; Validation: R.T. and C.N.; Visualization: I.F. Writing—original draft: A.L.P., F.C., R.T. and C.N.; Writing—review and editing: I.F., M.P.R., A.B.P. and F.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no financial support or funding from any institution, organization, or agency.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Search strategy.

Table A1.

Search strategy.

| Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed via MedLine | (“Curve of Spee” OR “Spee, Curve” OR “Spee Curve” OR “Spee’s curve” OR “Spee’s curvature” OR “curvature of occluding surface of the teeth” OR “curvature of the occlusal alignment of teeth”) AND (Orthodontics[Mesh] OR Orthodont* OR “Dental Occlusion”[Mesh] OR “Dental Occlusion*” OR “Occlusion, Dental” OR “Occlusions, Dental” OR “normal occlusion” OR “teeth occlusion” OR “tooth occlusion” OR “Occlusal Plane *” OR “Plane, Occlusal” OR “Planes, Occlusal” OR “Occlusal Guidance*” OR “Guidance, Occlusal”) |

| Web of Science All Databases | (“Curve of Spee” OR “Spee, Curve” OR “Spee Curve” OR “Spee’s curve” OR “Spee’s curvature” OR “curvature of occluding surface of the teeth” OR “curvature of the occlusal alignment of teeth”) AND (Orthodont * OR “Dental Occlusion *” OR “Occlusion, Dental” OR “Occlusions, Dental” OR “normal occlusion” OR “teeth occlusion” OR “tooth occlusion” OR “Occlusal Plane *” OR “Plane, Occlusal” OR “Planes, Occlusal” OR “Occlusal Guidance *” OR “Guidance, Occlusal”) |

| Embase | (‘curve of spee’ OR ‘spee, curve’ OR ‘spee curve’ OR ‘spee’s curve’ OR ‘spee’s curvature’ OR ‘curvature of occluding surface of the teeth’ OR ‘curvature of the occlusal alignment of teeth’) AND (‘orthodontics’/exp OR orthodont* OR ‘tooth occlusion’/exp OR ‘normal occlusion’ OR ‘teeth occlusion’ OR ‘tooth occlusion’ OR ‘dental occlusion*’ OR ‘occlusion, dental’ OR ‘occlusions, dental’ OR ‘occlusal plane’/exp OR ‘occlusal plane*’ OR ‘plane, occlusal’ OR ‘planes, occlusal’ OR ‘occlusal guidance’ OR ‘guidance, occlusal’) AND ([article]/lim OR [article in press]/lim OR [data papers]/lim OR [letter]/lim) |

| Cochrane | #1 “curve of spee” #2 “spee, curve” #3 “spee curve” #4 “spee’s curve” #5 “spee’s curvature” #6 “curvature of occluding surface of the teeth” #7 “curvatura of the occlusal alignment of teeth” #8 MeSH descriptor: [Orthodontics] explode all trees #9 orthodont * #10 MeSH descriptor: [Dental Occlusion] explode all trees #11 (dental NEXT occlusion *) #12 (occlusion * NEXT dental) #13 “normal occlusion” #14 “teeth occlusion” #15 “tooth occlusion” #16 (occlusal NEXT plane *) #17 (plane * NEXT occlusal) #18 (occlusal NEXT guidance *) #19 “guidance, occlusal” #20 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7) AND (#8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19) |

Table A2.

List of excluded studies.

Table A2.

List of excluded studies.

| Excluded Study | Reason for Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Amm, E. et al., 2022 [70] | No description of spee curve correction. The study compares the verticalization of molars in leveled or unlevelled COS, with different methods |

| Arnett, G. et al., 2022 [71] | Protocol description |

| Arnett, G. et al., 2022 [72] | No description of spee curve correction. |

| Baldridge, D., 1969 [73] | No description of spee curve correction. |

| Chattopadhyay, J. et al., 2023 [74] | Descriptive study without data on spee curve correction |

| Chu, Y. et al., 2009 [75] | Protocol description |

| Danguy, M. & Danguy-Derot, C., 2003 [76] | Descriptive study without data on spee curve correction |

| De Praeter, J. et al., 2002 [5] | No description of spee curve correction method. |

| Fauconnier, H. & Oosterbosch, J., 1949 [77] | No description of spee curve correction. |

| Ferguson, J W., 1990 [78] | Descriptive study without data on spee curve correction |

| Garcia, R., 1985 [79] | No description of spee curve correction. |

| Goel, P. et al., 2014 [80] | No description of spee curve correction. |

| Häll, B. et al., 2008 [81] | No description of spee curve correction method. |

| Hoppenreijs, T. et al., 1998 [82] | Descriptive study without data on spee curve correction |

| Martins, R.P., 2017 [83] | Descriptive study without data on spee curve correction |

| Mischler, W.A. & Delivanis, H.P., 1984 [84] | No description of spee curve correction method. |

| Ohannessian, P., 1979 [85] | No description of spee curve correction method. |

| Spengeman, W., 1968 [86] | Descriptive study without data on spee curve correction |

| Tremont, T.J. & Posnick, J.C., 2020 [87] | Descriptive study without data on spee curve correction |

| Wiechmann, D., 1999 [88] | Descriptive study without data on spee curve correction |

| Zemann, W. et al., 2012 [89] | No description of spee curve correction. |

| Zhang, L. et al., 2022 [90] | No description of spee curve correction. |

Table A3.

Assessing the risk of bias in in silico.

Table A3.

Assessing the risk of bias in in silico.

| Structured Summary | Scientific Background and Explanation of Rationale | Specific Objectives and/or Hypotheses | The Intervention for Each Group | Definition of Outcome | Sample Size | SEQUENCE Generation | Allocation Concealment Mechanism | Implementation | Blinding | Statistical Method | Outcomes and Estimation | Limitations | Funding | Protocol | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Brito, G. et al., 2019 [24] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N |

| Clifford, P.et al., 1999 [25] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N |

| Fawaz, P. et al., 2021 [26] | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Theerasopon, P. et al., 2019 [27] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N |

| Yeung, S. et al., 2024 [28] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Zhu, L. et al., 2024 [29] | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N |

Y—Yes; N—No.

Table A4.

Assessing the risk of bias in randomized controlled clinical trials.

Table A4.

Assessing the risk of bias in randomized controlled clinical trials.

| Randomization Process | Effect of Assignment to Intervention | Missing Outcome Data | Risk of Bias in Measurement of the Outcome | Risk of Bias in Selection of the Reported Result | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlQabandi, A. et al.,1999 [14] | H | H | H | L | L | High |

| Ba-Hattab, R. et al., 2023 [32] | L | H | H | L | H | High |

| Bernstein, R. et al., 2007 [33] | H | H | H | L | H | High |

| Dritsas, K. et al., 2022 [38] | L | H | H | L | H | High |

| Gravina, M. et al., 2013 [44] | H | H | H | L | H | High |

| Nasrawi, Y. et al., 2022 [54] | L | H | H | L | H | High |

| Preston, C. et al., 2008 [57] | H | H | H | L | H | High |

| Shakhtour, F., 2024 [61] | H | H | SC | SC | L | High |

| Theerasopon, P. et al., 2021 [65] | L | H | H | L | H | High |

L–Low, H—High; SC—Some concerns.

Table A5.

Assessing the risk of bias in non-randomized clinical studies.

Table A5.

Assessing the risk of bias in non-randomized clinical studies.

| Confounding Factors | Selection of Participants | Classification of Interventions | Deviations from Intended Interventions | Missing Data | Measurement of the Outcome | Selection of the Reported Result | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahammed, A. et al., 2014 [30] | L | M | S | L | L | L | L | S |

| Alshuraim, F. et al., 2024 [31] | L | M | S | L | L | L | L | S |

| Busenhart, D. M. et al., 2024 [34] | L | M | S | L | L | L | L | S |

| Chiqueto, K. et al., 2008 [35] | L | M | L | L | L | L | L | M |

| Chung, T. et al., 1997 [36] | L | M | S | L | L | L | L | S |

| Ciavarella, D. et al., 2024 [37] | L | M | L | L | L | L | L | M |

| Fawaz, V. et al., 2023 [39] | L | M | S | L | L | L | L | S |

| Feldman, E. et al., 2015 [40] | L | M | L | L | L | L | L | M |

| Freitas, K. et al., 2006 [41] | L | M | L | L | L | L | L | M |

| Givins, E.D., 1970 [42] | L | S | S | L | L | L | L | S |

| Goh, S. et al., 2022 [43] | L | M | L | S | S | L | L | S |

| Harini, A. et al., 2024 [45] | L | S | L | L | L | M | L | S |

| Hellsing, E., 1990 [46] | L | M | S | L | L | L | L | S |

| Jeong, H. et al., 2020 [47] | L | M | L | L | L | L | L | M |

| Koyama, T., 1979 [48] | L | M | S | L | L | L | L | S |

| Kravitz, N. et al., 2023 [49] | L | M | L | L | L | L | L | M |

| Lie, F. et al., 2006 [50] | L | M | S | L | L | L | L | S |

| Lim, Z. et al., 2023 [51] | L | M | S | S | S | L | L | S |

| Lupatini, P. et al., 2015 [52] | L | M | S | L | L | L | L | S |

| Martins, D. et al., 2012 [53] | L | M | L | L | L | L | L | M |

| Nawaz, A. et al., 2018 [55] | L | M | L | L | L | L | L | M |

| Pandis, N. et al., 2010 [56] | L | M | L | L | L | L | L | M |

| Rizvi, B. et al., 2013 [58] | L | M | L | L | L | L | L | M |

| Rozzi, M. et al., 2017 [59] | L | M | L | L | L | L | L | M |

| Rozzi, M. et al., 2019 [60] | L | M | L | L | L | L | L | M |

| Rozzi, M. et al., 2022 [9] | L | M | L | L | L | L | L | M |

| Shannon, K.R., Nanda R. S., 2004 [62] | L | M | S | L | L | L | L | S |

| Sinha, A. et al. 2024 [63] | S | M | L | L | L | M | L | S |

| Sondhi, A. et al., 1980 [64] | L | M | S | L | L | L | L | S |

L—Low risk of bias, M—Moderate risk of bias, S—Serious risk of bias.

References

- Proffit, W.; Fields, H.; Sarver, D. Contemporary Orthodontics, 4th ed.; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.P.S.; Tamizharasi, S. Significance of curve of Spee: An orthodontic review. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2012, 4, S323–S328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.D.; Caspersen, M.; Hardinger, R.R.; Franciscus, R.G.; Aquilino, S.A.; Southard, T.E. Development of the curve of Spee. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2008, 134, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalaf, Z.A.; Sghaireen, M.G.; Issrani, R.; Ganji, K.K.; Alruwaili, N.N.; Alsaleh, R.M.; Alruwaili, M.R.S.; Alabdali, M.F.; Alsirhani, M.A.R.; Alam, M.K. The Effect of Accentuation of Curve of Spee on Masticatory Efficiency-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Children 2023, 10, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Praeter, J.; Dermaut, L.; Martens, G.; Kuijpers-Jagtman, A.M. Long-term stability of the leveling of the curve of Spee. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2002, 121, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veli, I.; Ozturk, M.A.; Uysal, T. Curve of Spee and its relationship to vertical eruption of teeth among different malocclusion groups. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2015, 147, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halimi, A.; Benyahia, H.; Azeroual, M.F.; Bahije, L.; Zaoui, F. Relationship between the curve of Spee and craniofacial variables: A regression analysis. Int. Orthod. 2018, 16, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborn, J.W. Orientation of the masseter muscle and the curve of Spee in relation to crushing forces on the molar teeth of primates. Am. J. Phys. Anthr. 1993, 92, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozzi, M.; Tiberti, G.; Mucedero, M.; Cozza, P. Leveling the curve of Spee: Comparison between continuous archwire treatment and Invisalign system: A retrospective study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 162, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouten, J.C.; Enlow, D.H.; Rabine, M.; Phelps, A.E.; Swedlow, D. Morphologic factors in open bite and deep bite. Angle Orthod. 1983, 53, 192–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orthlieb, J.D. The curve of Spee: Understanding the sagittal organization of mandibular teeth. Cranio 1997, 15, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zoubi, E.M.; Al-Nimri, K.S. A comparative study between the effect of reverse curve of Spee archwires and anterior bite turbos in the treatment of deep overbite cases. Angle Orthod. 2022, 92, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.J.; Bates, S.B.; Ehlert, A.A.; Whiting, D.P.; Chen, S.S.H.; Bollen, A.M. Stability of deep-bite correction: A systematic review. J. World Fed. Orthod. 2012, 1, e89–e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlQabandi, A.K.; Sadowsky, C.; BeGole, E.A. A comparison of the effects of rectangular and round arch wires in leveling the curve of Spee. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1999, 116, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricketts, R.M. Bioprogressive therapy as an answer to orthodontic needs. Part I. Am J Orthod. 1976, 70, 241–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.; Hnat, W.P.; Johnson, B.E. The curve of Spee revisited. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1996, 110, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanda, R. The differential diagnosis and treatment of excessive overbite. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 1981, 25, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schudy, F.F. The association of anatomical entities as applied to clinical orthodontics. Angle Orthod. 1966, 36, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.F. The six keys to normal occlusion. Am. J. Orthod. 1972, 62, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggion, C.M. Guidelines for reporting pre-clinical in vitro studies on dental materials. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2012, 12, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito, G.M.; de Araújo Brito, H.H.; Marra, G.G.M.; Freitas, L.R.P.; Hargreaves, B.O.; Magalhães, P.A.A.; Oliveira, D.D. Pure Mandibular Incisor Intrusion: A Finite Element Study to Evaluate the Segmented Arch Technique. Materials 2019, 12, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, P.M.; Orr, J.F.; Burden, D.J. The effects of increasing the reverse curve of Spee in a lower archwire examined using a dynamic photo-elastic gelatine model. Eur. J. Orthod. 1999, 21, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawaz, P.; Amm, E.; Khoury, E. The curve of Spee and its levelling in different vertical skeletal patterns: A 3D set-up study. Int. Orthod. 2021, 19, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theerasopon, P.; Kosuwon, W.; Charoemratrote, C. Stress assessment of mandibular incisor intrusion during initial leveling in continuous arch system with different archwire shapes of superelastic nickel-titanium: A three-dimensional finite element study. Int. J. Health Allied Sci. 2019, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, S.; Owen, B.; Heo, G.; Carey, J.P.; Major, P.W.; Romanyk, D.L. In vitro measurement of the initial forces and moments generated for a curve of Spee malocclusion with labial and lingual archwire forms. Angle Orthod. 2025, 95, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, L.; Wang, W.; Deng, W.W. Effects of different patterns of movement for correcting a deep curve of Spee with clear aligners on the anterior teeth: A finite element analysis. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahammed, A.R.Y.; Ganiger, C.C.; Shetty, V.; Sunny, S.; Shetty, S.; Pawar, R.; Suresh, K.V. Post-retention Development of Curve of Spee in Pre-adjusted Edgewise Appliance Cases, Its Correlation to Dentoskeletal Parameters: An In vitro Study. J. Int. Oral Health 2014, 6, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Alshuraim, F.; Burns, C.; Morgan, D.; Jabr, L.; Rossouw, P.E.; Michelogiannakis, D. The second molar dilemma in orthodontics: To bond or not to bond? Angle Orthod. 2024, 94, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba-Hattab, R.; Abu Alhaija, E.S.; Nasrawi, Y.H.; Taha, N.; Daher, H.; Daher, S. Leveling the curve of Spee using different sized archwires: A randomized clinical trial of blood flow changes. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 2943–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, R.L.; Preston, C.B.; Lampasso, J. Leveling the curve of Spee with a continuous archwire technique: A long term cephalometric study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2007, 131, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busenhart, D.M.; Schätzle, M.; Eliades, T.; Papageorgiou, S.N. Long-term stability of curve of Spee depth among orthodontically treated patients: A retrospective longitudinal study. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2024, 27, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiqueto, K.; Martins, D.R.; Janson, G. Effects of accentuated and reversed curve of Spee on apical root resorption. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2008, 133, 261–268, quiz 328.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, T.S.; Sadowsky, P.L.; Wallace, D.D.; McCutcheon, M.J. A three-dimensional analysis of mandibular arch changes following curve of Spee leveling in nonextraction orthodontic treatment. Int. J. Adult Orthod. Orthognath. Surg. 1997, 12, 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ciavarella, D.; Fanelli, C.; Suriano, C.; Campobasso, A.; Lorusso, M.; Ferrara, D.; Maci, M.; Esposito, R.; Tepedino, M. Curve of Spee modification in different vertical skeletal patterns after clear aligner therapy: A 3D set-up retrospective study. Prog. Orthod. 2024, 25, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dritsas, K.; Alharbi, M.; Kouvelis, G.; Kloukos, D.; Gkantidis, N. Effect of the timing of second molar bonding on the duration of the mandibular arch levelling: A randomized clinical trial. Eur. J. Orthod. 2022, 44, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawaz, V.; Purushothaman, B.; Siyo, R.K.N.; Naseem, K.T.; Ashok, A.; Bavitha, T.K. Investigation of the change in the degree of Frankfort mandibular plane angle after levelling the curve of spee in different malocclusion groups. J. Orthod. Sci. 2023, 12, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, E.; Kennedy, D.B.; Aleksejuniene, J.; Hannam, A.G.; Yen, E.H. Mandibular changes secondary to serial extractions compared with late premolar extractions and controls. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2015, 148, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, K.M.S.; Crepaldi, A.; Freitas, M.R.; Fonseca, R.C.; Crepaldi, M.V. Estudo da recidiva da sobremordida relacionada com a curva de Spee, em pacientes Classe II, divisão 1, na fase pós-contenção. Rev. Dent. Press Ortod. Ortop. Facial 2006, 11, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givins, E.D. A cephalometric analysis of the degree of change in the curve of Spee of non-extraction orthodontic cases before and after treatment. Bull. Pac. Coast Soc. Orthod. 1970, 45, 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, S.; Dreyer, C.; Weir, T. The predictability of the mandibular curve of Spee leveling with the Invisalign appliance. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 162, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravina, M.A.; Brunharo, I.H.V.P.; Fraga, M.R.; Artese, F.; da Silva Campos, J.; Vitral, R.W.F.; Quintão, C.C.A. Clinical evaluation of dental alignment and leveling with three different types of orthodontic wires. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2013, 18, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harini, A.; Kadiveti, A.; Vivek Reddy, G.; Alahari, S.S.K.; Singaraju, G.S.; Mandava, P. Predictors of Curve of Spee Leveling in Class II Division 1 Malocclusion Treated with Reverse Curve of Spee Archwires: An Observational Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e67163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellsing, E. Increased overbite and craniomandibular disorders—A clinical approach. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1990, 98, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.J.; Kim, S.-H.; Choi, B.-J.; Han, S.-H.; Ahn, H.-W. The Envelope of Segmental Movement and Airway Changes After Mandibular Anterior Subapical Osteotomy in Skeletal Class II Protrusion Patients. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2020, 31, 668–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, T. A comparative analysis of the curve of Spee (lateral aspect) before and after orthodontic treatment—With particular reference to overbite patients. J. Nihon Univ. Sch. Dent. 1979, 21, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kravitz, N.D.; Hansa, I.; Vaid, N.R.; Moshiri, M.; Adel, S.M. Does age influence deep overbite correction with Invisalign? A prospective study evaluating mandibular incisor intrusion in adolescents vs. adults. Angle Orthod. 2024, 94, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, F.; Kuitert, R.; Zentner, A. Post-treatment development of the curve of Spee. Eur. J. Orthod. 2006, 28, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Z.W.; Meade, M.J.; Weir, T. The predictability of maxillary curve of Spee leveling with the Invisalign appliance. Angle Orthod. 2023, 93, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupatini, P.; Vitral, R.; Campos, M.; Gravina, M.; Fraga, M.; Mota Júnior, S. Assessment of Long-Term Stability of Leveling of the Curve of Spee after Orthodontic Treatment in Mesocephalic Patients—A Pilot Study. Pesqui. Bras. Odontopediatria Clínica Integr. 2015, 15, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, D.R.; Tibola, D.; Janson, G.; Maria, F.R.T. Effects of intrusion combined with anterior retraction on apical root resorption. Eur. J. Orthod. 2012, 34, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrawi, Y.H.; Alhaija, E.S.A.; Al Maaitah, E.F. Efficacy of lower arch leveling, lower incisors’ root resorption, and pain associated with the correction of curve of Spee using different orthodontic archwires: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 7107–7120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Munir, D.; Burhan Ud Din, M. An Expressive Research to Assess the Skeletal Variations after Arc of Spee Flattening with Non-Stop Archwire in Terms of Mean Change and Change Percentage. INDO Am. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 11, 12491–12497. [Google Scholar]

- Pandis, N.; Polychronopoulou, A.; Sifakakis, I.; Makou, M.; Eliades, T. Effects of levelling of the curve of Spee on the proclination of mandibular incisors and expansion of dental arches: A prospective clinical trial. Australas. Orthod. J. 2010, 26, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, C.B.; Maggard, M.B.; Lampasso, J.; Chalabi, O. Long-term effectiveness of the continuous and the sectional archwire techniques in leveling the curve of Spee. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2008, 133, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, B.; Shah Faisal, S.; Siddique, H. Changes in Skeletal and Dental Structures after Leveling the Curve of Spee with Continuous Archwire. Ann. Abbassi Shaheed Hosp. Karachi Med. Dent. Coll. 2013, 18, 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rozzi, M.; Mucedero, M.; Pezzuto, C.; Cozza, P. Leveling the curve of Spee with continuous archwire appliances in different vertical skeletal patterns: A retrospective study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2017, 151, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozzi, M.; Mucedero, M.; Pezzuto, C.; Lione, R.; Cozza, P. Long-term stability of curve of Spee levelled with continuous archwires in subjects with different vertical patterns: A retrospective study. Eur. J. Orthod. 2019, 41, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhtour, F.; Al-Nimri, K. Comparison between effects of reverse curve of Spee nickel titanium archwire and stainless steel archwires with and without torque on the lower incisors in deep overbite treatment: A randomized control study. Angle Orthod. 2025, 95, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, K.R.; Nanda, R.S. Changes in the curve of Spee with treatment and at 2 years posttreatment. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2004, 125, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Jain, S.; Kunjappan, S.M.; Jai, V.A.; Kamble, R.; Jadhav, A.V. Assessing Cephalometric Changes in Deep Bite Correction: An Analysis of Class II Division 1 Orthodontic Patients Treated with the Reverse Curve of Spee Archwire. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2024, 16 (Suppl. 4), S3245–S3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondhi, A.; Cleall, J.F.; BeGole, E.A. Dimensional changes in the dental arches of orthodontically treated cases. Am. J. Orthod. 1980, 77, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theerasopon, P.; Lindauer, S.J.; Charoemratrote, C. Separation of aligning and leveling stages to control mandibular incisor inclination: A randomized clinical trial. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2021, 26, e2119378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccuzzi, M.; Cosola, S.; Butera, A.; Genovesi, A.; Laborante, T.; Castaldo, A.; Zizza, A.; Oldoini, G.; Nota, A.; Tecco, S. Predictability of ClinCheck in Overbite Correction with Aligners: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, S. Curve of Spee—From orthodontic perspective. Indian J. Dent. 2015, 6, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, R. Stability of deep overbite correction. Eur. J. Orthod. 1983, 5, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razdolsky, Y.; Sadowsky, C.; BeGole, E.A. Occlusal contacts following orthodontic treatment: A follow-up study. Angle Orthod. 1989, 59, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amm, E.; Amm, C.E.; Vaden, J. Effect of Class II elastics on different mandibular arch preparation stabilized with aligners and stainless-steel wires: A FEM study. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2022, 25, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, G.W.; D’Agostino, A.; Grendene, E.; McLaughlin, R.P.; Trevisiol, L. Combined orthodontic and surgical open bite correction: Principles for success. Part 2. Angle Orthod. 2022, 92, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, G.W.; Trevisiol, L.; Grendene, E.; McLaughlin, R.P.; D’Agostino, A. Combined orthodontic and surgical open bite correction. Angle Orthod. 2022, 92, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldridge, D.W. Leveling the curve of Spee: Its effect on mandibular arch length. JPO J. Pract. Orthod. 1969, 3, 26–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay, J.; Fatima, A.; Naukarkar, P.; Sarate, S.; Kumar, M.; Patel, M. A Comparative Study Of Different Intrusion Methods And Their Effect On Maxillary Incisors. J. Pharm. Negat. Results 2023, 14, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.M.; Bergeron, L.; Chen, Y.R. Bimaxillary protrusion: An overview of the surgical-orthodontic treatment. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2009, 23, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danguy, M.; Danguy-Derot, C. Treatment of overbite and leveling. L’Orthodontie Française 2003, 74, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauconnier, H.; Oosterbosch, J. The inverted Spee curve. Arch. Stomatol. 1949, 4, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, J.W. Lower incisor torque: The effects of rectangular archwires with a reverse curve of Spee. Br. J. Orthod. 1990, 17, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R. Leveling the curve of Spee: A new prediction formula. J. Charles H. Tweed Int. Found 1985, 13, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, P.; Tandon, R.; Agrawal, K.K. A comparative study of different intrusion methods and their effect on maxillary incisors. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2014, 4, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häll, B.; Jämsä, T.; Soukka, T.; Peltomäki, T. Duration of surgical-orthodontic treatment. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2008, 66, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppenreijs, T.J.; Voorsmit, R.A.; Freihofer, H.P. Open bite deformity in amelogenesis imperfecta. Part 1: An analysis of contributory factors and implications for treatment. J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 1998, 26, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, P.M. Early vertical correction of the deep curve of Spee. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2017, 22, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischler, W.A.; Delivanis, H.P. Comparison study between three tooth positioners. Am. J. Orthod. 1984, 85, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohannessian, P. Une approche mathématique de la correction et du nivellement de la courbe de Spee. L’Orthodontie Française 1979, 50, 710–711. [Google Scholar]

- Spengeman, W.G. The curve of Spee leveling appliance (Cosla). Am. J. Orthod. 1968, 54, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremont, T.J.; Posnick, J.C. Selected Orthodontic Principles for Management of Cranio-Maxillofacial Deformities. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 32, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiechmann, D. Lingual orthodontics (part 2): Archwire fabrication. J. Orofac. Orthop. 1999, 60, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemann, W.; Metzler, P.; Jacobsen, C.; Obwegeser, J.A. Segmental distraction osteogenesis of the anterior alveolar process using tooth-borne devices: Is it skeletal movement or mainly dental tipping? J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 70, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lin, S.; Chen, J.; Huang, L.; Huang, Z.; Li, H. Risk factors for midcourse correction during treatment of first series of aligners with Invisalign. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 162, e96–e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).