1. Introduction

Accurate and timely diagnosis prediction is paramount in healthcare, as it directly influences patient outcomes and treatment efficacy. Over the years, computational methods have evolved from symbolic systems to advanced machine learning and deep learning models. Although these methods have shown significant success, they often struggle with a trade-off between performance and interpretability, which is a vital issue in healthcare environments where comprehending the rationale behind a diagnosis is crucial.

Early computational diagnostic tools predominantly relied on symbolic reasoning, utilising predefined logic rules to infer conclusions from medical data [

1,

2]. These symbolic frameworks are commonly referred to as Good Old-Fashioned AI (GOFAI) [

3,

4]. These systems offered high transparency but were constrained by the strictness of human-crafted rules, limiting their adaptability to the complexities of real-world clinical scenarios. Several conventional machine learning models, such as LR and SVM [

5], improved generalisation by learning patterns from data. However, these models frequently demanded considerable feature engineering and, in some cases, sacrificed interpretability for improved performance. CNN and RNN are popular deep learning architectures [

6,

7,

8] that have significantly improved predictive performance, particularly with unstructured data. However, the “black-box” characteristics of these systems have raised concerns about transparency and trustworthiness in healthcare applications [

9,

10].

Recent advancements have resulted in the integration of LLMs in the healthcare industry, leveraging their ability to understand and generate text that mimics human language [

11]. LLMs can examine vast volumes of unstructured data, including medical records, to identify subtle and complex patterns. However, they inherit the interpretability challenges of deep learning models and often demand significant computational power, restricting their practical application in numerous healthcare settings.

The lack of interpretability and reasoning capability in conventional AI systems remains a key barrier to clinical adoption. Clinicians and healthcare providers require not only accurate predictions but also justifiable insights that align with established medical reasoning. There is thus a strong motivation to design AI models that integrate domain knowledge and logical constraints into the learning process, bridging the gap between statistical learning and symbolic reasoning. Neuro-symbolic AI (NeSy) represents an emerging paradigm that unites the structured reasoning of symbolic systems with the adaptive learning strengths of neural networks. This hybrid approach aims to bridge the gap between performance and explainability, making it appropriate for healthcare applications where both are paramount. Logical Neural Networks (LNNs), a subset of NeSy, have demonstrated the potential to integrate domain-specific knowledge through logical rules, thereby enhancing both accuracy and transparency in diagnosis prediction tasks [

12,

13,

14].

Building upon this motivation, the study aims to develop an explainable and interpretable AI framework for diabetes prediction that unites medical domain knowledge with data-driven learning. Specifically, we introduce a Logic Tensor Network (LTN)-based neuro-symbolic framework that embeds first-order logic (FOL) medical axioms into the neural network through trainable thresholds incorporated directly into the loss function. This approach enables the model to learn from both empirical data and domain knowledge simultaneously, ensuring medical reasoning consistency during training and inference.

To make the study more comprehensive and to gain a better overview of neurosymbolic integration for explainable and interpretable systems, we have defined the following research questions:

RQ1: How does the performance of LTN with trainable thresholds compare with the traditional machine learning models in the diabetes prediction task?

RQ2: How does an LTN-based neurosymbolic framework introduce interpretability, explainability and reasoning in the diabetes prediction task?

RQ3: What are the effects of different symbolic components on the overall performance of the LTN-based neurosymbolic framework?

The key contribution of this work is the design of an LTN-based neuro-symbolic model with trainable medical thresholds that integrates clinical axioms directly into the learning process through differentiated loss functions. This design enables interpretable, logic-consistent, and high-performing diabetes prediction by allowing the model to learn from both empirical data and structured medical knowledge. By embedding first-order logic constraints during training, rather than relying on post-hoc interpretability, the proposed framework ensures that predictions remain clinically meaningful and explainable. This study thereby introduces an LTN with trainable medical thresholds combined with clinical axioms and differentiated losses. The research is guided by three key questions (RQ1–RQ3) that evaluate performance, interpretability, and the influence of symbolic knowledge on prediction quality. We have also prepared a Streamlit-based web interface to demonstrate the proof of concept, which can be utilized for real-time diabetes prediction.

An overview of similar studies related to diabetic predictions is provided in

Section 2. The dataset description and data preprocessing steps are described in

Section 3. Details of the custom loss function and the overall methodology covering medical predicate definitions, logical formulation, training, and inference, can be found in

Section 4 and

Section 5. An overview of the evaluation metrics, results, and ablation studies is included in

Section 7,

Section 8 and

Section 9, whereas based on these results, the proposed research questions are addressed in

Section 10. Finally, the study concludes with a proof of concept, demonstrating the practical implementation and conclusions in

Section 11 and

Section 12.

2. Related Work

Diabetes prediction has been an active area of research in which both conventional machine learning (ML) and modern deep learning (DL) techniques have been applied extensively. Recent advancements also explore explainable AI (XAI) and neuro-symbolic reasoning to enhance model interpretability and trustworthiness in clinical contexts. This section reviews the main research trends, categorized into four subdomains.

2.1. Traditional Machine Learning Approaches for Diabetes Prediction

Classical ML models such as Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and Decision Trees (DT) have been widely used for diabetes prediction due to their efficiency and interpretability. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) developed the well-known Pima Indians Diabetes Dataset, which remains a standard benchmark for comparative analysis. Numerous studies have utilized this dataset to compare traditional and advanced algorithms.

For instance, Sisodia (2023) [

15] applied LR, SVM, and DT classifiers, achieving an accuracy of 78.69% with SVM. Similarly, Elluri et al. (2025) [

16] employed ensemble techniques and feature selection methods, improving predictive performance with a maximum accuracy of 81.2%. Chang et al. (2022) [

17] evaluated DT, RF, and NB, obtaining accuracies of 94.4%, 94%, and 91%, respectively, even with minimal preprocessing. Ahmed et al. (2024) [

18] reported random forest achieving 80% accuracy and an AUC of 0.83, and with Naive Bayes reported an AUC of 0.81 while also employing cross-validation.

2.2. Deep Learning Approaches

Deep learning models have demonstrated improved performance in capturing nonlinear relationships within clinical data. Huma et al. (2020) [

19] employed a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), achieving 98.07% accuracy on the Pima dataset through optimized hyperparameters. Zhang et al. (2024) [

20] proposed DiabetesNet, a Back-Propagation Neural Network (BPNN)-based framework, reaching 89.81% accuracy. Similarly, Dutt et al. (2018) [

21] used a Multi-Layer Feedforward Neural Network (MLFNN) and achieved 82.5% accuracy. These works underscore the potential of DL in feature abstraction and high predictive accuracy, though often at the expense of interpretability.

2.3. Explainable and Interpretable AI in Diabetes Risk Prediction

With the increasing deployment of AI in medical diagnosis, model interpretability has become essential. Explainable AI (XAI) methods aim to provide insights into model decisions using tools such as SHAP, LIME, and attention visualization. For example, Li et al. (2025) [

22] proposed an interpretable framework combining Gradient Boosting with SHAP values for diabetes risk explanation. Similarly, Kutlu et al. [

23] introduced interpretability in the XGBoost prediction of diabetes risk using the SHAP method, which provides valuable information on the prediction of the model. These approaches, while improving interpretability, often rely on post-hoc explanations that do not inherently encode reasoning.

2.4. Neuro-Symbolic and Logic-Based Methods

To address the gap between learning and reasoning, neuro-symbolic frameworks such as Logic Tensor Networks (LTNs) and Logical Neural Networks (LNNs) have been developed. LTNs, proposed by Badreddine et al. (2022) [

24], unify deep learning with First-Order Logic (FOL), allowing symbolic constraints to guide learning. In healthcare, Lu et al. (2025) [

13] applied LNNs to diabetes diagnosis, achieving 80.52% accuracy and an AUC of 0.8457, outperforming LR and RF while providing reasoning capability. Similarly, Chen et al. (2025) [

25] discussed several studies and methodologies in which LTN-based reasoning is applied to clinical risk prediction, showing improved explainability without compromising performance.

2.5. Summary and Research Gap

While ML and DL approaches achieve high predictive accuracy, most lack intrinsic reasoning and transparent decision making. Post-hoc XAI methods improve interpretability but do not enable logical consistency. Neuro-symbolic frameworks, such as LTNs, provide a promising direction by integrating reasoning with learning. Drawing inspiration from the study conducted by Lu et al. (2025) [

13], we present a neuro-symbolic approach using the logic tensor network (LTN) framework. This approach not only maintains acceptable accuracy but also incorporates reasoning capabilities, offering a more interpretable and explainable solution for medical diagnosis tasks.

2.6. Protocol Comparability

It is important to note that reported performance figures on the Pima Indian Diabetes dataset vary widely across studies, often due to differences in preprocessing, data splitting, and evaluation protocols. There are some studies where authors have reported extremely high accuracies such as 98.07% as mentioned by Huma et al. (2020) [

19] in their study. They have utilized specific data handling strategy to handle invalid zero values, shuffled sampling and model validation. On the other head, in most of the studies the result is not reported using cross-validation. Such inconsistencies limit the direct comparability of reported results across studies.

3. Dataset Description

The Pima Indians Diabetes Dataset serves as a well-known standard dataset for tasks related to predicting diabetes. It consists of medical diagnostic measurements for female patients of Pima Indian heritage, aged 21 years and above. The dataset consists of 768 instances with eight numerical input features and a binary target label, which indicates the presence or absence of diabetes. The eight input features are as follows:

Number of pregnancies;

Plasma glucose concentration (mg/dL);

Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg);

Triceps skinfold thickness (mm);

2-Hour serum insulin (mu U/mL);

Body mass index (BMI, weight in kg/(height in m2));

Diabetes pedigree function (a genetic risk score);

Age (years).

The target variable is a binary label, with 0 denoting the absence of diabetes and 1 denoting its presence. The dataset has an unequal distribution of classes, and no techniques for imputation or balancing are utilized to assess the model’s performance based on the original, imbalanced class distribution.

In this study, the data set is normalized using the standard scaler (Z-score normalization) and missing values are handled using median imputation before training the Logic Tensor Network (LTN) model for the prediction of diabetes.

Table 1 shows the summary of the variables with invalid zeros, the percentage of these values, and the distribution before and after computation.

4. Loss Function

We integrate domain knowledge into the training process through a hybrid loss function that unites binary cross-entropy loss (BCE) (

) with fuzzy logic-based axiom satisfaction loss (

). The total loss is defined as follows:

Here, the hyperparameter

balances the contribution of the BCE loss and the axiom satisfaction component.

is the aggregated fuzzy satisfaction score and (

) is the total fuzzy loss defined as follows:

where:

is the supervision satisfaction degree from the labeled data;

is the aggregated satisfaction of medical axioms;

is a weight controlling the influence of domain knowledge axioms;

SatAgg denotes the fuzzy aggregation function used in Logic Tensor Networks.

This formulation encourages the model not only to minimize prediction error but also to adhere to predefined medical constraints, improving interpretability and robustness.

5. Methodology

The implementation strategy of the LTN-based Neuro-symbolic framework is discussed in this section. We briefly discuss the logic tensor network, along with the implementation of the medical predicates aligned with clinical standards. The formulation of medical axioms and their integration into the learning process using LTNtorch framework is also discussed.

5.1. Overview of Logic Tensor Network

LTNs combine a sub-symbolic component with first-order logic (FOL) by embedding logical axioms into the training process. FOL can represent facts and rules, where facts are the known truths and rules are the logical statements that connect facts and allow inference. They enable the incorporation of domain knowledge, expressed as logical axioms, directly into the learning process. This integration allows models to perform both data-driven learning and logical reasoning [

24]. In LTNs, the predicates are represented by the neurons, which can be feedforward neural networks, and different logical connectives such as AND, OR, NOT, FORALL, and EXISTS are implemented using fuzzy logic operators. LTNs use neural networks to learn and predict properties and relationships from raw data and first-order logic rules to encode knowledge. The neural predicates provide fuzzy truth values, and the logic layer uses these fuzzy truth values to evaluate logical formulas and provide a consistency measure for reasoning. LTNs provide interpretable decisions with the help of domain knowledge as logic rules, and due to the integration of a neural component, they can also handle both structured and unstructured data. In this study, we have used the version

v1.0.2 of the

LTNtorch framework, a PyTorch-based implementation of LTNs [

26] using

PyTorch version of

2.6.0. The

LTNtorch framework grounds the medical axiom in a tensor to make these differentiable and trainable.

5.2. Medical Predicates and Feature Representation

In order to integrate domain-specific knowledge into the learning process, we define a set of logical predicates that are based on the well-established risk indicators of the WHO and the ADA for diabetes. These predicates capture threshold-based conditions related to the features, including glucose level, body mass index (BMI), age, and diabetes pedigree function (DPF).

Table 2 gives an overview of the predicates with their clinical definition and medical basis.

5.3. Logical Formulation

The predicates defined in

Table 2 are encoded as First-Order Logic (FOL) axioms, also known as medical knowledge axioms. These axioms describe both risk-enhancing and risk-reducing associations with diabetes. These axioms are integrated into the training process using the

LTNtorch framework. In general, these axioms enforce clinically consistent reasoning.

First-order logic enables the representation of general rules using quantified variables, logical predicates, and connectives such as implication (→), conjunction (∧), and negation (¬). The universal quantifier (∀) is used to denote that the logical statement applies to all individuals in the domain (i.e., all patients x in our case). We define three categories of axioms as follows:

Risk-enhancing axioms:

These rules encode conditions that increase the likelihood of diabetes, but do not guarantee a diagnosis and influence the overall fuzzy logic formulation.

Risk-reducing axioms: These rules reduce the likelihood of diabetes without guaranteeing a negative diagnosis but influence the overall decision-making process of the model.

Consistency constraints: These mutually exclusive constraints are implemented to prevent logical contradictions in the learned model, ensuring that predictions adhere to classical logic properties.

5.4. Implementation of Predicates Using Trainable Thresholds

The candidate thresholds are initialized on the basis of the medical standards of the ADA and WHO. The thresholds are trainable, which allows the model to adapt to the dataset’s distribution while being guided by clinical knowledge. Each predicate is implemented as a differentiable function, producing a truth value in [0, 1] to represent fuzzy membership. Formally, each predicate except

Diabetic is modeled as a trainable threshold function:

where:

is the patient feature corresponding to the predicate;

is the trainable threshold;

s is the slope (typically fixed at 10); and

denotes the sigmoid function.

The

Diabetic predicate is implemented as a feed-forward neural network, as shown in

Figure 1. It outputs a fuzzy truth value in the range

, representing the likelihood of diabetes:

where:

x is the patient feature vector;

and are weight matrices and biases for layer i;

denotes batch normalization at layer i;

is the exponential linear unit activation;

Dropout is applied to prevent overfitting; and

is the sigmoid function mapping the output to .

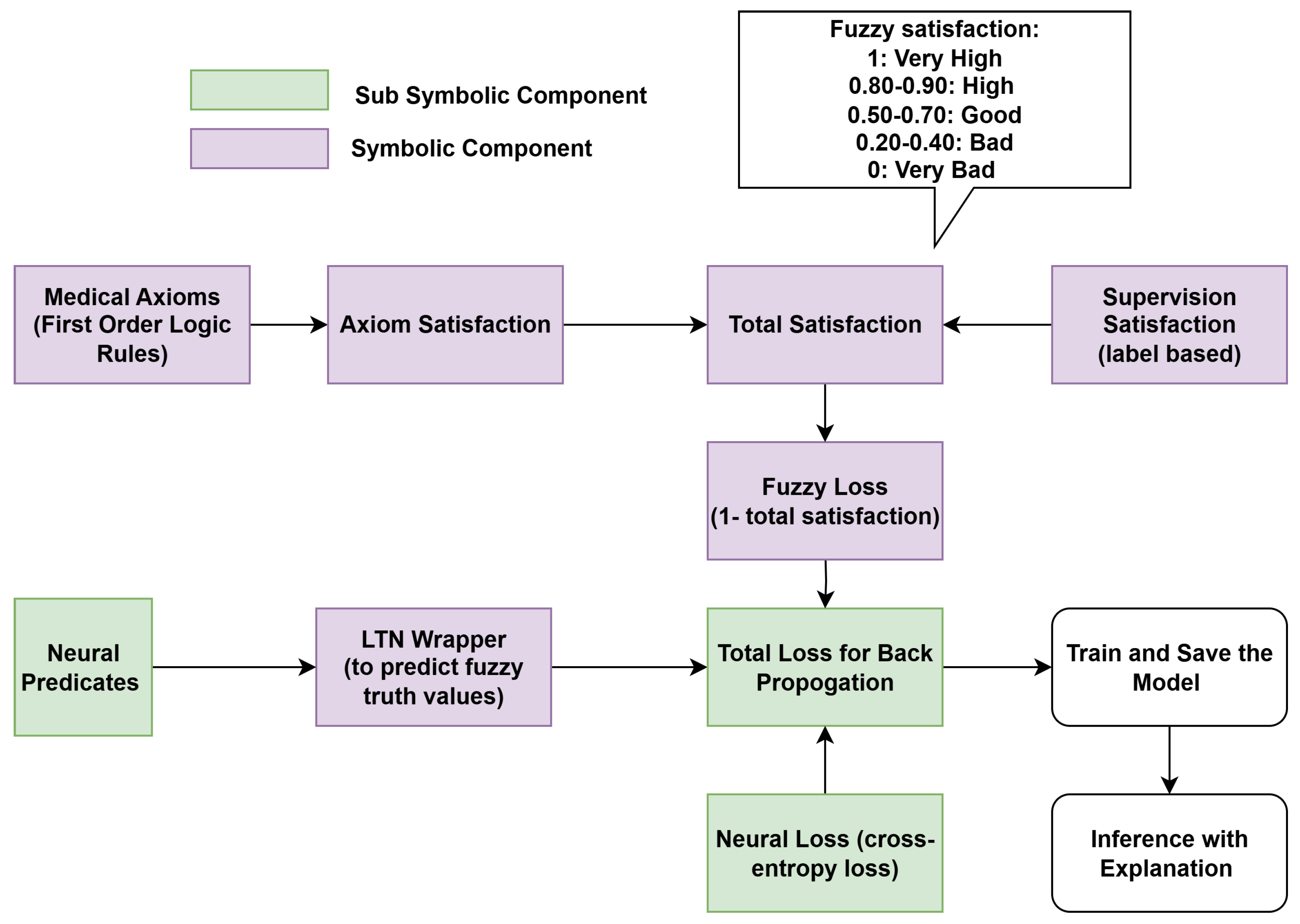

5.5. Integration of Medical Axioms in Training

To embed domain-specific medical knowledge into model training, we jointly optimize the Diabetic neural network and the trainable threshold predicates under the guidance of first-order logic (FOL) axioms. The axioms, categorized as risk-enhancing and risk-reducing, encode both positive and negative associations between patient features and diabetes risk. Logical connectives are implemented as differentiable operators using the

LTNtorch framework, which allows the evaluation of each axiom as a continuous satisfaction score. During training, the model jointly optimizes the empirical loss, which is the cross-entropy between predicted and true diabetic labels and logic loss, which is the average degree of violation across all axioms. The workflow of the proposed framework is illustrated in

Figure 2.

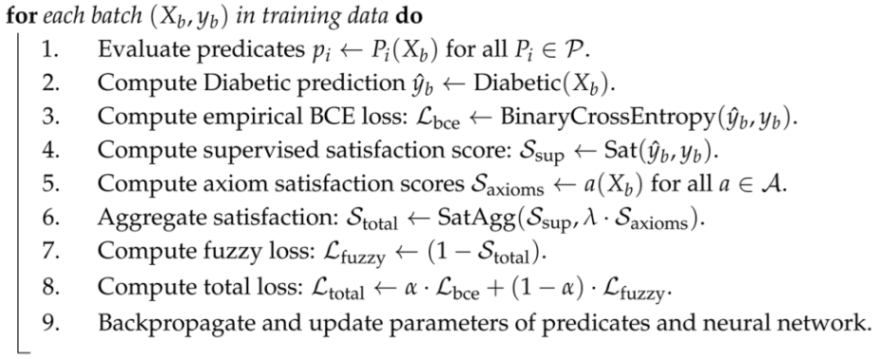

Algorithm 1 summarizes the complete workflow for training the LTN with trainable predicates and FOL axioms and the inference. At each epoch, the model computes predicate truth values, evaluates logical satisfaction scores, calculates the total loss, and updates both neural network parameters and predicate thresholds via gradient descent.

| Algorithm 1: Diabetes Prediction with LTN using Trainable Thresholds |

- Input:

Patient feature vector x, trainable predicates , axioms , Diabetic neural network, hyperparameters , . - Output:

Fuzzy truth value and explanation of prediction.

Training Phase:![Applsci 15 11806 i001 Applsci 15 11806 i001]() Inference Phase: - 1.

Evaluate predicates for input x. - 2.

Compute using the neural network. - 3.

Compute axiom satisfaction scores and combine with prediction. - 4.

Output final fuzzy truth value and explanation.

|

6. Experimental Settings

The experiments were carried out on a local machine equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4060 GPU (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with 8 GB of VRAM and 16 GB of system RAM, utilising CUDA version 11.8 to leverage GPU acceleration for training processes. All models were implemented in PyTorch and trained on a standard computing environment. No additional data augmentation or synthetic oversampling techniques were applied.

To ensure fair and consistent evaluation, all models in this study were trained and tested using a 5-fold stratified cross-validation strategy. The dataset was split into 5 folds, ensuring that each fold maintained the original class distribution. A fixed random seed of 42 was used to guarantee reproducibility.

For neural network-based models, the same architecture was adopted across all experiments. For each fold, the models were trained over 500 epochs using the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001.

There are two hyperparameters in the loss function, including

and

. We performed a grid search-based sensitivity analysis on

and

to analyze their impact on model performance and logical satisfaction. Based on the grid search result in

Table 3, the configuration

and

was selected because it provides the best trade-off between predictive performance and logical satisfaction.

Table 4 shows the summary of different parameters set during training. For the classical machine learning models, some parameters were set to the default value.

7. Evaluation Metrics

For a comprehensive assessment of the proposed models, we have employed the following standard metrics pertinent to binary classification tasks.

Instead of relying solely on accuracy, considering multiple metrics provides a more reliable assessment. Accuracy offers a general measure of correct predictions, but it can be misleading when class imbalance exists, and it also does not reflect the consequences of false positives and false negatives. In this study, we deal with an imbalanced dataset, so recall and precision are also important. Recall reflects the capability of the model to correctly recognize true cases of diabetes. High recall is considered in medical applications because false negatives may be harmful and delay the treatment process. On the other hand, precision determines how many of the patients who are predicted as diabetic are truly diabetic. False positives may lead to unnecessary follow-up, but these are generally less harmful than missed diagnoses. The F1-score gives a balanced metric by considering both precision and recall, which helps to understand the trade-off between false positives and false negatives. AUC-ROC helps to assess the model’s discriminative ability between different classes, which is important for medical settings because it evaluates the discriminative power of the model across thresholds. The problem with AUC-ROC is that it might give misleadingly high performance estimates in imbalance datasets since it is less sensitive to the minority class. To handle this situation, we have also considered PR-ROC which can handle imbalance situations and gives clear picture when the positive class is smaller than the negative class.

8. Results

Table 5 presents a comparative summary of the proposed LTN model’s performance alongside several empirical machine learning models, including LR, SVM, RF, K-NN, NB, and a standalone NN. A 5-fold stratified cross-validation strategy is employed for evaluation, ensuring that each fold maintains the original class distribution. All models are evaluated on the Pima Indian Diabetes dataset using the same experimental setup and consistent hyperparameters. The architecture of the standalone neural network is identical to the one used as the Diabetic predicate in the LTN model (

Figure 1). To convert probabilistic outputs into binary predictions, the optimal threshold is determined from the ROC curve computed on the validation set within each cross-validation fold and then applied to the corresponding test subset, selecting the point that maximizes the difference between the true positive rate and false positive rate, instead of using a 0.5 cut-off-based approach, which is sometimes misleading in healthcare applications.

The LTN model with trainable thresholds outperforms all other baseline models across all performance metrics. The model achieves a recall of 0.83, which is particularly important in medical diagnostics, as it reduces the number of false negatives. The F1 score of 0.80, AUC-ROC of 0.92 and PR-AUC of 0.86 further demonstrate that the model shows a balanced performance and robust discriminative capability.

Figure 3 provides a visual comparison of key metrics, highlighting the consistent advantage of the LTN framework over classical models.

We have performed the Wilcoxon signed-rank test [

29] to evaluate whether the LTN model statistically outperforms other machine learning models in terms of F1 score. All models were trained and evaluated using identical stratified 5-fold splits, ensuring that the Wilcoxon test was applied on paired results from the same folds. The null hypothesis (

) assumes no difference between the models, while the alternative hypothesis (

) assumes that the LTN achieves higher performance. Since multiple hypotheses were tested, the Holm–Bonferroni correction was applied to control the family-wise error rate at

. The results, summarized in

Table 6, indicate that the LTN significantly outperforms all baseline models.

In this study, we made the thresholds of the predicates trainable to introduce interpretability. During training, initial candidate values were set based on ADA/WHO guidelines (e.g., OGTT 2h: 140/200 mg/dL for glucose predicates). To compute the final trained value of the predicates threshold, we ran the experiments five times with different random seeds and recorded the results. The mean value of each predicate threshold, along with the lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence interval, is reported in

Table 7. Importantly, the training process respects all hard axioms, ensuring that the final thresholds remain clinically consistent while learning from the data.

The quantitative findings suggest that the LTN model consistently surpasses the baseline models in various evaluation metrics, especially in maintaining a balance between precision and recall.

9. Ablation Study

To assess the role of different components of the proposed Logic Tensor Network (LTN) model, we have conducted an ablation study on the Pima Indian Diabetes dataset.

Table 8 summarizes the performance under four setups: (i) LTN without axioms or threshold supervision (only supervision satisfaction loss), (ii) LTN with fixed thresholds, (iii) LTN with trainable thresholds, and (iv) LTN with automatic rule generation using a decision tree.

The ablation study reveals the contribution of each of the components, such as the medical axioms, and fixed and trainable thresholds. In the first case, LTN without any domain guidance, with supervision satisfaction and binary cross-entropy loss, achieves comparatively lower AUC-ROC (0.90), F1 score (0.79) and Stotal (0.65). Introducing fixed thresholds along with medical axioms improves all metrics except recall, particularly F1 (0.80), highlighting the benefit of incorporating domain knowledge as constraints, which also improves clinical interpretability. Trainable thresholds further enhance performance by increasing precision (0.78), AUC-ROC (0.92) and Stotal (0.72), indicating that adapting thresholds to dataset-specific distributions provides additional flexibility while improving model interpretability. Finally, integrating automatic rule generation using a decision tree with candidate thresholds increases recall (0.88) while slightly reducing precision (0.73), suggesting that data-driven rule refinement improves detection of positive cases at the cost of false positives. Overall, these results confirm that the integration of medical axioms with trainable thresholds improves model performance while introducing interpretability. The predictions are accompanied by clinically aligned explanations derived from the medical axioms, which introduce explainability and reasoning into the decision-making process.

10. Discussion

The Logic Tensor Network (LTN)-based neurosymbolic model with trainable thresholds achieved an accuracy of 86%, precision of 78%, recall of 83%, F1-score of 80%, an AUC-ROC of 0.92 and PR-AUC of 0.86, outperforming all classical machine learning approaches including Logistic Regression (LR), Standalone Neural Network (NN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), K-Nearest Neighbors (K-NN), Random Forest (RF), and Naive Bayes (NB), as shown in

Table 5 which answers RQ1. This demonstrates that integrating medical axioms with data-driven learning can improve both predictive performance and interpretability.

The medical axioms with the candidate thresholds are defined by following clinical standards. These thresholds are also trainable and are updated by gradient descent during the backpropagation process. This makes the framework clinically interpretable. Model training is jointly guided by data and axioms, enabling reasoning over predefined medical rules. During inference, the model provides a final prediction along with an explanation of the prediction in terms of predicate evaluation and axiom satisfaction. These ensure explainability and reasoning of the framework, and hence answer RQ2.

To address RQ3, we refer to

Table 8 in the ablation study. The results show that the LTN without medical knowledge does not achieve optimal performance, while incorporating medical axioms with fixed thresholds enhances the model’s overall performance. Furthermore, employing a trainable threshold improves both the overall F1 score and the interpretability of the model.

Despite these promising results, there are some limitations which should be acknowledged. The Pima Indian dataset contains entries of adult women only from the Pima heritage; therefore, the thresholds derived may not generalize to other populations without recalibration. Additionally, training over 500 epochs on a relatively small dataset poses a potential risk of overfitting. This risk was mitigated using the AdamW optimizer, which provides effective weight decay, and a dropout rate of 0.2 in the neural components of the model. Future work may explore early stopping, and testing on larger and more diverse cohorts to further enhance generalizability.

Other future directions include extending the LTN framework to other chronic diseases, incorporating multi-modal data sources, and investigating automated axiom refinement strategies to enhance both performance and interpretability in clinical decision support applications.

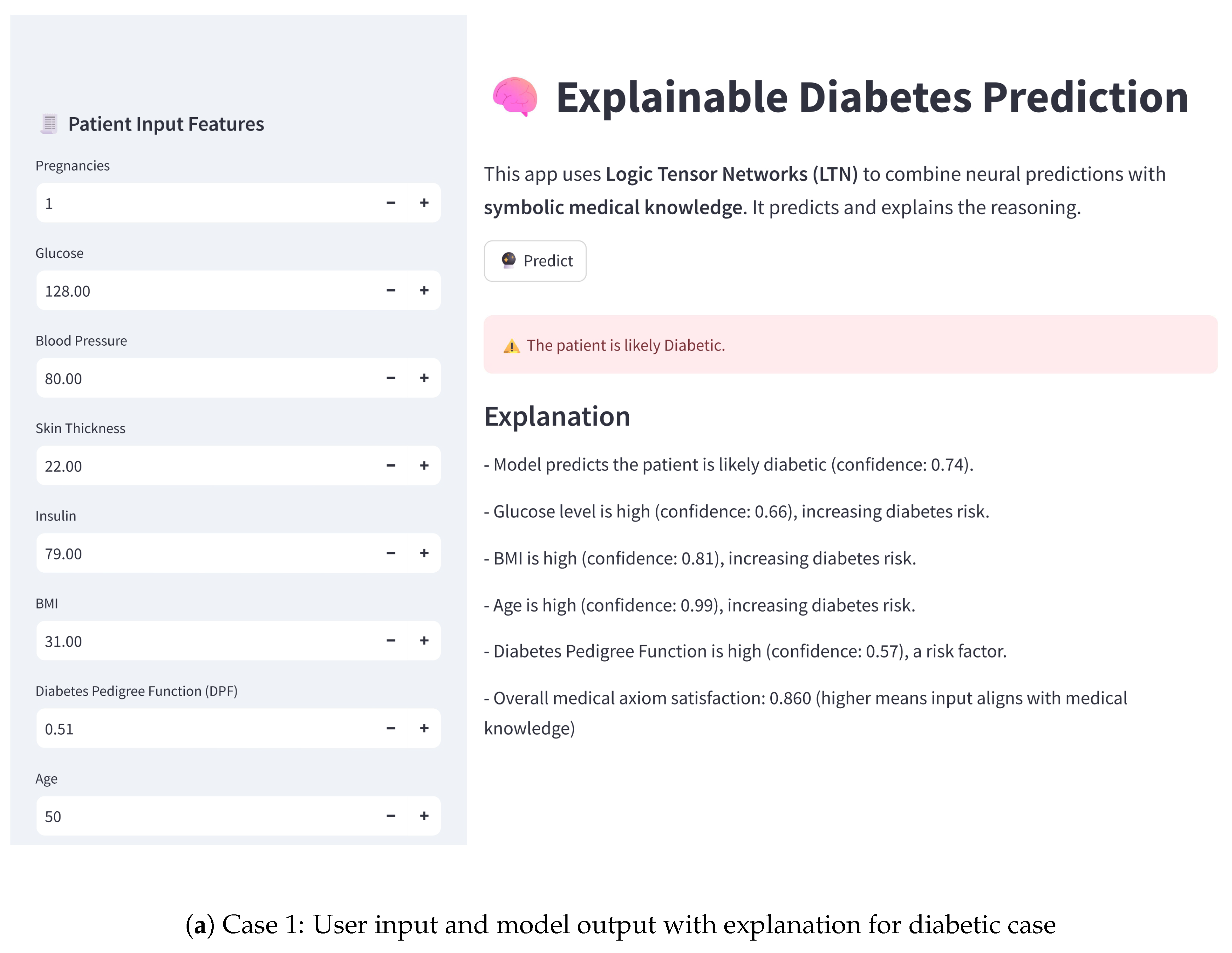

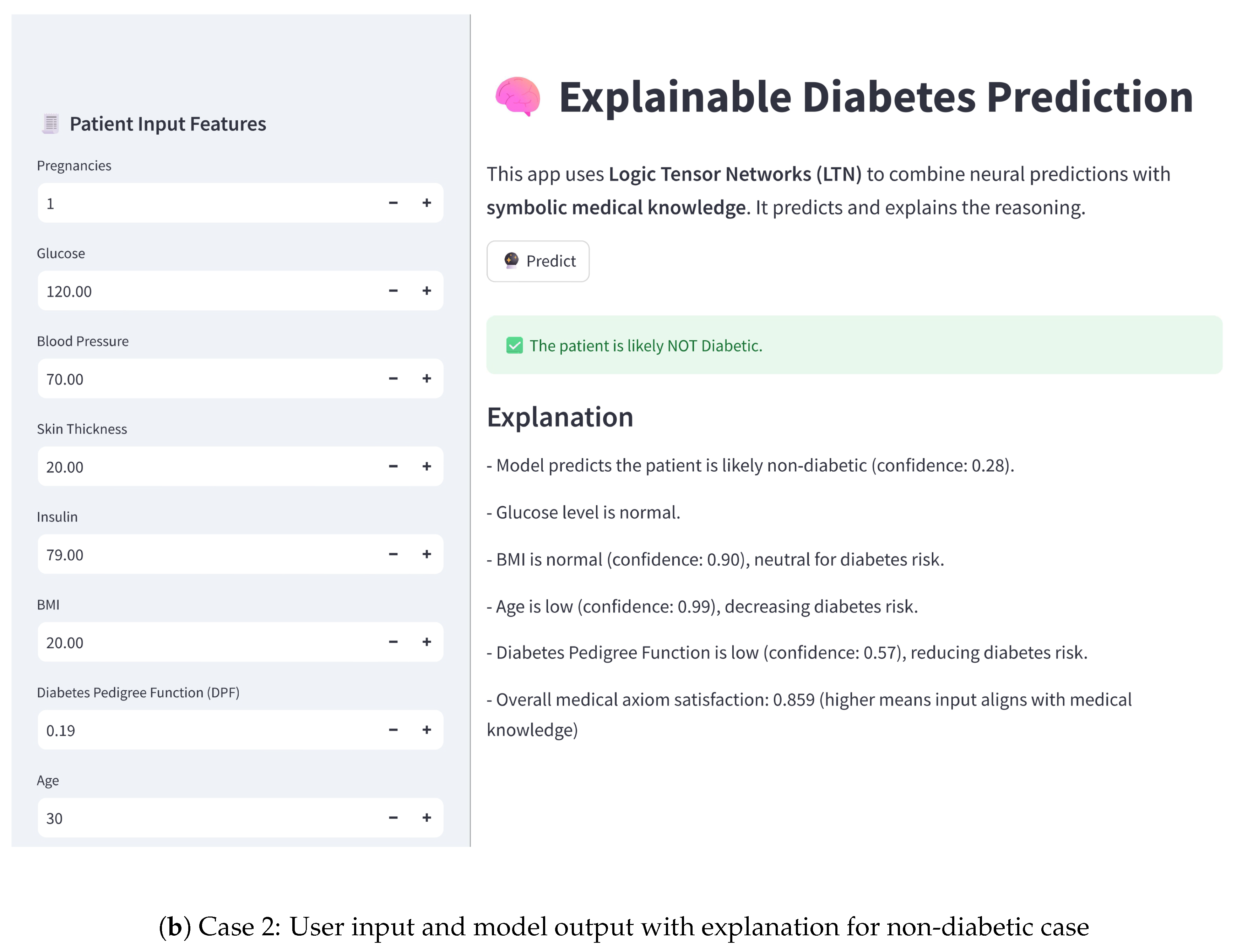

11. Proof of Concept

To demonstrate the practical applicability of the proposed model, we have developed an interactive user interface using Streamlit. This user interface (UI) enables users to input patient features and receive real-time diabetes risk predictions, along with explanations based on the neurosymbolic model, highlighting the model’s potential for clinical decision support. The practical implementation of a diabetes detection system using the LTN-based neurosymbolic AI is shown in

Figure 4. For the model prediction case, it shows the confidence that the patient is diabetic. Therefore, for the positive case, the value is higher, whereas in the negative case, the value is lower than 50%.

12. Conclusions

This work highlights the effectiveness of neurosymbolic AI in enhancing predictive model performance by integrating domain knowledge through logical constraints, specifically using first-order logic (FOL) as medical axioms. The proposed approach not only demonstrates promising accuracy but also enables guided and interpretable training, ensuring that the model’s predictions are consistent with expert medical knowledge.

While this study focuses on diabetes prediction within the healthcare context, the underlying methodology is broadly applicable across domains where incorporating structured domain knowledge can improve model reliability and transparency. Although FOL are used here as the knowledge representation, other forms, such as knowledge graphs, can also be integrated as domain knowledge bases, paving the way for richer, more interpretable, and robust AI models.

In the current implementation, during inference, a prediction is provided along with an explanation based on the satisfaction of the medical axioms and the confidence score of the predicates. The proposed LTN-based neurosymbolic model thus presents a sustainable direction for interpretable AI, achieving promising performance even on a relatively small dataset. However, external validation on larger and more diverse clinical datasets will be essential before translating these findings into real-world medical practice. Future integration with large language models (LLMs) can further enhance the explainability by providing more structured explanations, though at the cost of increased model complexity and power consumption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M., A.F., F.P. and G.D.P.; methodology, S.M., A.F., F.P. and G.D.P.; software, S.M., A.F., F.P. and G.D.P.; validation, S.M., A.F., F.P. and G.D.P.; formal analysis, S.M., A.F., F.P. and G.D.P.; investigation, S.M., A.F., F.P. and G.D.P.; resources, S.M., A.F., F.P. and G.D.P.; data curation, S.M., A.F., F.P. and G.D.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M., A.F., F.P. and G.D.P.; writing—review and editing, S.M., A.F., F.P. and G.D.P.; visualization, S.M., A.F., F.P. and G.D.P.; supervision, A.F., F.P. and G.D.P.; project administration, A.F., F.P. and G.D.P.; funding acquisition, A.F., F.P. and G.D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the project “Models for Explainable Reasoning and Learning through Integration (MERLIN)” (CUP/ID: PRA2025001), PRA 2025 – Progetti di Ricerca di Ateneo dell’ Università Pegaso (Decreto N. 231/2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LTN | Logic Tensor Network |

| FOL | First Order Logic |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| SVM | Support vector Machine |

| RF | Random Forest |

| K-NN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| NB | Naive Bayes |

| NN | Neural Network |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| AUC-ROC | Area Under the Curve (AUC)-Receiver-Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC) |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| LLMs | Large Language Models |

| NeSy | Neuro-Symbolic |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| NIDDK | National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases |

| MLP | Multi Layer Perceptron |

| MLFNN | Multi-Layer Feed Forward Neural Networks |

| BPNN | Back-Propagation Neural Network |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| DPF | Diabetes Pedigree Function |

| ADA | American Diabetes Association |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| OGTT | Oral Glucose Tolerance Test |

| AdamW | Adaptive Moment Estimation with Weight Decay |

| TP | True Positive |

| TN | True Negative |

| BN | Batch Normalization |

| ELU | Exponential Linear Unit |

| UI | User Interface |

| BCE | Binary Cross-Entropy |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| SHAP | SHapley Addictive exPlanations |

| LIME | Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations |

| lbfgs | Limited-memory Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno |

References

- Eyasu, K.; Jimma, W.; Tadesse, T. Developing a Prototype Knowledge-Based System for Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetes Using Data Mining Techniques. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2020, 30, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandhania, V.; Choubey, D.; Paul, S. Rule based diagnosis system for diabetes. Biomed. Res. 2017, 28, 5196–5209. [Google Scholar]

- Emma, L. The Evolution of Artificial Intelligence: From Symbolic AI to Deep Learning. March 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Lawrence-Emma/publication/390544723_The_Evolution_of_Artificial_Intelligence_From_Symbolic_AI_to_Deep_Learning/links/67f32bd095231d5ba5b99670/The-Evolution-of-Artificial-Intelligence-From-Symbolic-AI-to-Deep-Learning.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Ilkou, E.; Koutraki, M. Symbolic Vs Sub-symbolic AI Methods: Friends or Enemies? CIKM 2020, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassannataj Joloudari, J.; Saadatfar, H.; Dehzangi, I.; Shamshirband, S. Computer aided decision-making for predicting liver disease using PSO-based optimized SVM with feature selection. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2019, 17, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barolli, L.; Ferraro, A. A Prediction Approach in Health Domain Combining Encoding Strategies and Neural Networks. In Advances on P2P, Parallel, Grid, Cloud and Internet Computing; Barolli, L., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junejo, A.; Kaabar, M.; Ullah, I.; Khan, R.; Ma, Y.-K. Deep Learning in Cancer Diagnosis and Prognosis Prediction: A Minireview on Challenges, Recent Trends, and Future Directions. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2021, 2021, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Stewart, W.; Sun, J.; Ng, K.; Yan, S. Recurrent Neural Networks for Early Detection of Heart Failure from Longitudinal Electronic Health Record Data. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2019, 12, e005114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, K.; Qayyum, A.; Ghaly, M.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Razi, A.; Qadir, J. Explainable, trustworthy, and ethical machine learning for healthcare: A survey. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 149, 106043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, C.; Janneh, M.; Spaziani, S.; Calcagno, V.; Bernardi, M.L.; Iammarino, M.; Verdone, C.; Tagliamonte, M.; Buonaguro, L.; Pisco, M.; et al. Assessment of Primary Human Liver Cancer Cells by Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Raman Spectroscopy. Cells 2023, 12, 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Xu, C.; Guo, Y.; Zhan, Z.; Ding, S.; Wang, J.; Xu, K.; Fang, Y.; et al. Large Language Models for Disease Diagnosis: A Scoping Review. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.00097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, A.; Galli, A.; La Gatta, V.; Minocchi, M.; Moscato, V.; Postiglione, M. Few Shot NER on Augmented Unstructured Text from Cardiology Records. In Advances in Internet, Data & Web Technologies; Barolli, L., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Li, R.; Sagheb, E.; Wen, A.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Fan, J.W.; Liu, H. Explainable Diagnosis Prediction through Neuro-Symbolic Integration. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2410.01855. [Google Scholar]

- Aversano, L.; Bernardi, M.L.; Cimitile, M.; Iammarino, M.; Verdone, C. An Enhanced UNet Variant for Effective Lung Cancer Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Padua, Italy, 18–23 July 2022; IEEE: Padua, Italy, 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisodia, D.; Sisodia, D. Prediction of Diabetes using Classification Algorithms. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 132, 1578–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elluri, S. Enhanced Diabetes Prediction Using a Hybrid Machine Learning Framework with Feature Selection and Weighted Ensemble Classification. Healthcare 2025, 35, 16157–16173. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, V.; Bailey, J.; Xu, Q.; Sun, Z. Pima Indians diabetes mellitus classification based on machine learning (ML) algorithms. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 35, 16157–16173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Khan, J.; Arsalan, M.; Jalal, K.; Shahat, A.; Alhalmi, A.; Naaz, S. Machine Learning Algorithm-Based Prediction of Diabetes Among Female Population Using PIMA Dataset. Healthcare 2024, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huma, S.; Ahuja, S. Deep learning approach for diabetes prediction using PIMA Indian dataset. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2020, 19, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ahmed, K.A.; Hasan, M.R.; Gedeon, T.; Hossain, M.Z. DiabetesNet: A Deep Learning Approach to Diabetes Diagnosis. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.07483. [Google Scholar]

- Dutt, M.; Nunavath, V.; Goodwin, M. A Multi-layer Feed Forward Neural Network Approach for Diagnosing Diabetes. In Proceedings of the 2018 11th International Conference on Developments in eSystems Engineering (DeSE), Cambridge, UK, 2–5 September 2018; pp. 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ding, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, S.; Hu, Z.; Ma, Z.; Li, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y. Interpretable machine learning method to predict the risk of pre-diabetes using a national-wide cross-sectional data: Evidence from CHNS. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutlu, M.; Dönmez, T.B.; Freeman, C. Machine Learning Interpretability in Diabetes Risk Assessment: A SHAP Analysis. Comput. Electron. Med. 2024, 1, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badreddine, S.; d’Avila Garcez, A.; Serafini, L.; Spranger, M. Logic Tensor Networks. Artif. Intell. 2022, 303, 103649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, D.; Chen, J.Y. A Study on Neuro-Symbolic Artificial Intelligence: Healthcare Perspectives. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.18213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, T.; Serafini, L.; Aiolli, F. LTNtorch: PyTorch Implementation of Logic Tensor Networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.16045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, D.M.W. Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.16061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, T. Introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2006, 27, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, D.; Neuhauser, M. Wilcoxon-Signed-Rank Test. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Lovric, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 1658–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).