Limosilactobacillus reuteri in Pediatric Oral Health: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Guidelines

2.2. Selection Criteria

- -

- Articles published from January 2011 to 31 December 2024;

- -

- Studies involving patients under 18 years of age;

- -

- Studies evaluating the effect of L. reuteri in the oral cavity;

- -

- Randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

- -

- Articles whose abstracts do not address the research topic;

- -

- Studies on adult patients;

- -

- Studies of the effects of L. reuteri that are not in the oral cavity;

- -

- Systematic review, or a review, or a meta-analysis or books and documents.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Search Strategy

2.5. Selection of Articles and Data Collection

2.6. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

3. Results

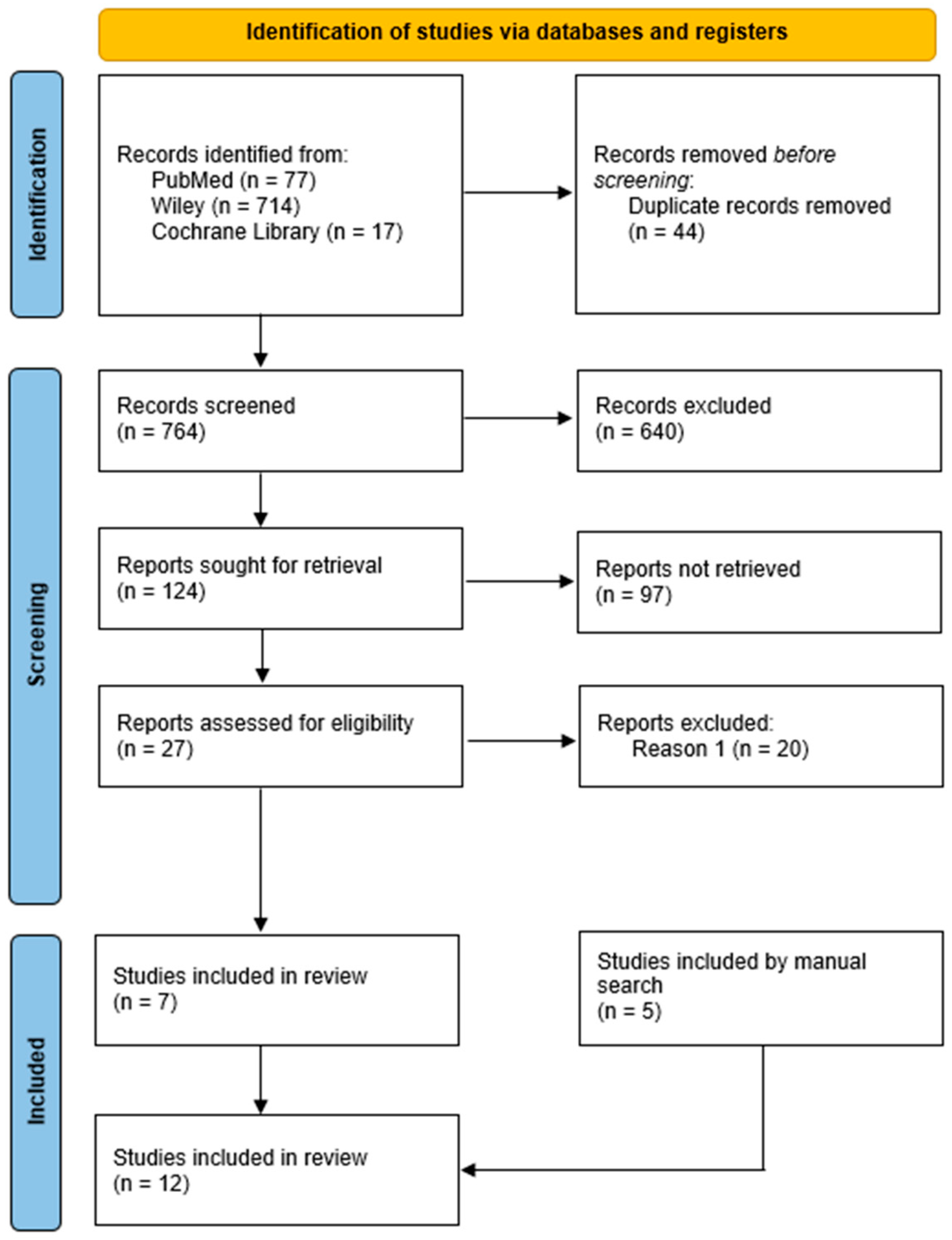

3.1. Selection of Articles

3.2. Sample Characteristics for Study Quality

3.3. Characteristics of the Included Studies

| Was the Randomization Method Adequate? | Was the Allocation Method Adequate? | Were the Groups Similar at the Start of the Study? | Were the Participants Blinded? | Were the Professionals Who Administered the Interventions Blinded? | Were the Outcome Assessors Blinded? | Were the Interventions Clearly Described and Applied Equally in Both Groups? | Was the Primary Outcome Clearly Defined and Measured? | Was There an Intention-to-Treat Analysis? | Were Losses and Exclusions Described? | Were Complications or Adverse Events Reported? | Were the Study Results Accurate and Reliable? | Were the Study Results Relevant to Clinical Practice? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stensson et al., 2014 [43] | Y | U | Y | N | U | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Gizani et al., 2016 [36] | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | N | Y | Y |

| Hasslöf et al., 2022 [37] | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Keller et al., 2014 [38] | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | N | Y | Y |

| Alamoudi et al., 2018 [25] | Y | U | Y | U | U | U | Y | Y | U | U | N | Y | Y |

| Kaur et al., 2018 [44] | Y | U | Y | U | U | U | Y | Y | U | U | N | Y | Y |

| Bolla et al., 2022 [39] | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | N | Y | Y |

| Cildir et al., 2012 [40] | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | N | Y | Y |

| Tehrani et al., 2016 [45] | Y | U | Y | U | U | U | Y | Y | U | U | N | Y | Y |

| Ebrahim et al., 2022 [41] | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | N | Y | Y |

| García et al., 2021 [42] | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | N | Y | Y |

| Alforaidi et al., 2021 [46] | Y | U | Y | U | U | U | Y | Y | U | U | N | Y | Y |

| Authors and Year of Publication | Study Design | Objectives | Population | Duration of Supplementation | Bacterial Strain | Probiotic Vehicle | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stensson et al., 2014 [43] | Single-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial | Assess the influence on oral health at the age of 9 with daily oral supplementation of L. reuteri ATCC 55730 given to mothers during the last month of pregnancy and to children throughout their first year of life. | 113 children | For mothers: 4 weeks before birth For children: during their first year of life | L. reuteri ATCC 55730 | Drops |

|

| Gizani et al., 2016 [36] | Double-blind RCT | Evaluate the effect of daily probiotic lozenges administration, on white spot lesion formation and salivary counts of lactobacilli and S. mutans in patients with fixed orthodontic appliances. | 85 patients | 17 months | L. reuteri (DSM 17938 and ATCC PTA 5289) | Lozenges |

|

| Hasslöf et al., 2022 [37] | Double-blind RCT | Determine the effect of probiotic-containing drops on the recurrence of dental caries in preschool children. | 38 children | 12 months | L. reuteri (DSM 17938 and ATCC PTA 5289) | Drops |

|

| Keller et al., 2014 [38] | Double-blind RCT | Investigate the impact of probiotic lactobacilli tablets on early caries lesions in adolescents using quantitative light-induced fluorescence. | 36 adolescents | 3 months | L. reuteri (DSM 17938 and ATCC PTA 5289) | Tablets |

|

| Alamoudi et al., 2018 [25] | RCT | Investigate the role of L. reuteri probiotic lozenges on caries-associated salivary bacterial counts (S. mutans and Lactobacillus), dental plaque accumulation, and salivary buffer capacity in preschool children. | 178 children | 28 days | L. reuteri (DSM 17938 and ATCC PTA 5289) | Lozenges |

|

| Kaur et al., 2018 [44] | RCT | Assess the impact of probiotic and xylitol-containing chewing gums on salivary S. mutans counts, plaque and gingival scores, following the intervention. | 40 children | 3 weeks | L. reuteri (ATCC 55730 and ATCC PTA 5282) | Chewing gums |

|

| Bolla et al., 2022 [39] | Double-blind RCT | Evaluate the effects of L. reuteri, B. bifidum, and their combination on salivary S. mutans counts in children, and the sustainability of their action. | 60 subjects | 14 days | Bifidobacterium bifidum (UBBB 55, MTCC 5398) and L. reuteri (UBLRu 87, MTCC 5403) | Curds |

|

| Cildir et al., 2012 [40] | Double-blind, randomized crossover design | Investigate the effect of the probiotic L. reuteri on salivary S. mutans and Lactobacillus levels in children with cleft lip/palate using a novel drop containing L. reuteri. | 19 operated cleft lip/palate children | 25 days | L. reuteri (DSM 17938 and ATCC PTA 5289) | Drops |

|

| Tehrani et al., 2016 [45] | RCT | Evaluate the effect of a probiotic drop containing L. rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium infantis, and L. reuteri on salivary counts of S. mutans and Lactobacillus in children of 3 to 6 years old. | 61 children | 2 weeks | L. rhamnosus ATCC 15820, Bifidobacterium infantis ATCC 15697 and L. reuteri ATCC 55730 | Drops |

|

| Ebrahim et al., 2022 [41] | Double-blind RCT | Determine the effectiveness of the commercially available Lorodent Probiotic Complex in reducing plaque accumulation and S. mutans levels in adolescent orthodontic patients. | 60 adolescents | 28 days | Streptococcus. salivarius K12, Lacticaseibacillus paracasei, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, L. acidophilus, Ligilactobacillus salivarius and L. reuteri | Lozenges |

|

| García et al., 2021 [42] | Double-blind RCT | Examine the impacts of a probiotic on oral health indices in adolescents and analyze the relationships between these indices, dietary habits, and oral hygiene. | 27 adolescents | 28 days | L. reuteri (DSM 17938 and ATCC 5289) | Tablets |

|

| Alforaidi et al., 2021 [46] | RCT | Analyze the impact of probiotics on biofilm acidogenicity and the levels of salivary S. mutans and lactobacilli in orthodontic patients. | 28 subjects | 3 weeks | L. reuteri (DSM 17938 and ATCC PTA 5289) | Drops |

|

4. Discussion

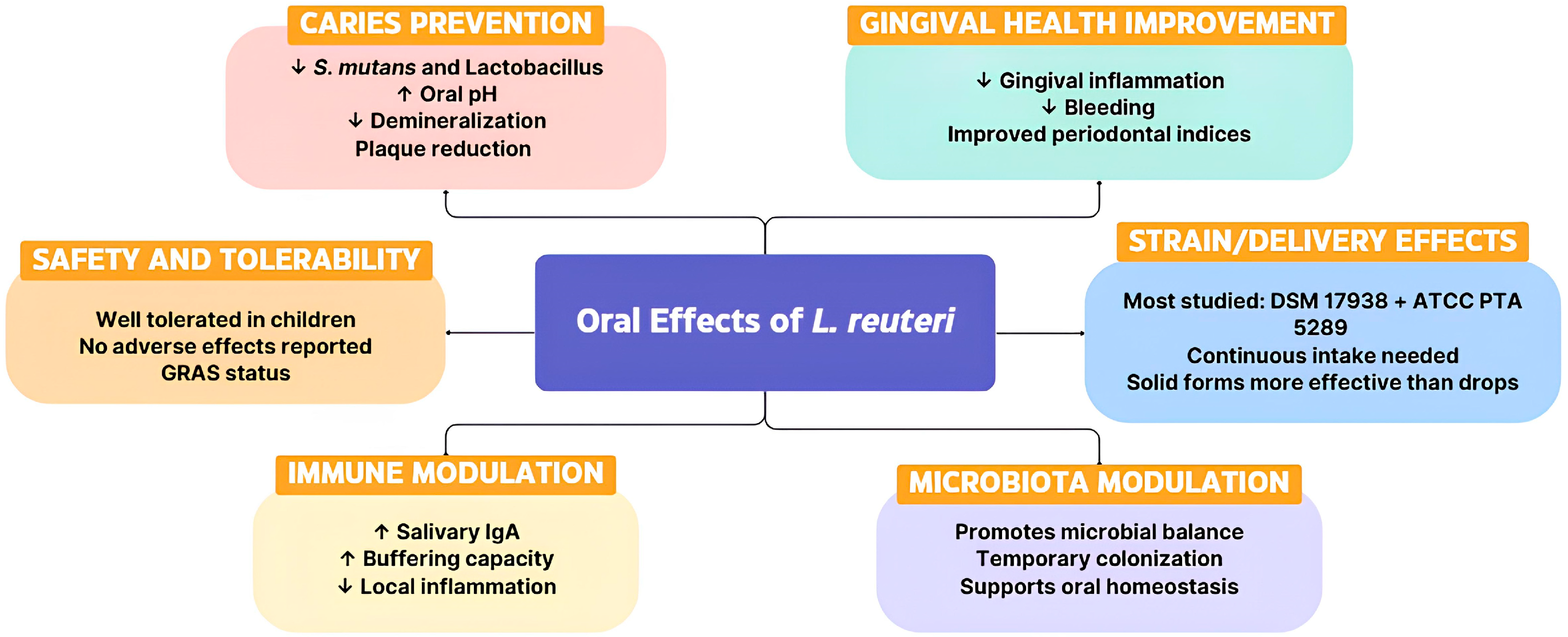

4.1. Limosilactobacillus Reuteri as an Alternative Approach Against Pediatric Dental Caries

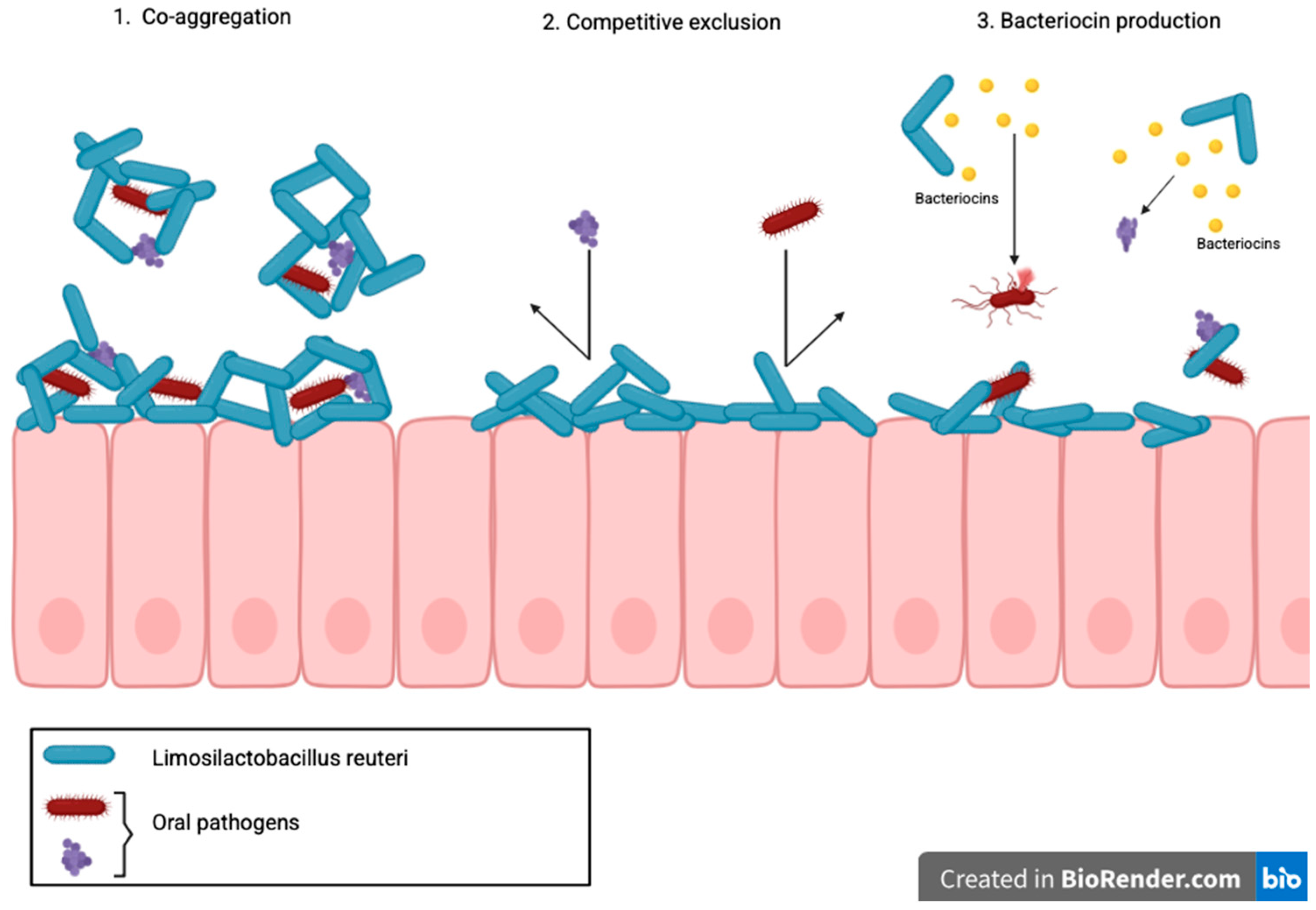

4.1.1. Mechanisms of Action of L. Reuteri in Caries Prevention

4.1.2. Early Life Interventions and Influence of Breastfeeding

4.1.3. Effectiveness of Different Probiotic Delivery Vehicles in Children

4.1.4. Probiotics in Pediatric Orthodontic Patients

4.2. Limosilactobacillus Reuteri as an Adjuvant on Periodontal Therapy

4.2.1. Effects in Children and Adolescents

4.2.2. Effects During Orthodontic Treatment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| B. bifidum | Bifidobacterium bifidum |

| BI | Bleeding Index |

| ECC | Early Childhood Caries |

| GI | Gingival Index |

| L. acidophilus | Lactobacillus acidophilus |

| L. casei | Lactobacillus casei |

| L. reuteri | Limosilactobacillus reuteri |

| L. rhamnosus | Lactobacillus rhamnosus |

| pH | potential of hydrogen |

| PI | Plaque Index |

| PICOS | Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| qPCR | quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| SIgA | Secretory IgA |

| S. mutans | Streptococcus mutans |

References

- Ptasiewicz, M.; Grywalska, E.; Mertowska, P.; Korona-Głowniak, I.; Poniewierska-Baran, A.; Niedźwiedzka-Rystwej, P.; Chałas, R. Armed to the Teeth—The Oral Mucosa Immunity System and Microbiota. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.L.; Mark Welch, J.L.; Kauffman, K.M.; McLean, J.S.; He, X. The Oral Microbiome: Diversity, Biogeography and Human Health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 22, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajão, A.; Silva, J.P.N.; Almeida-Nunes, D.L.; Rompante, P.; Rodrigues, C.F.; Andrade, J.C. Limosilactobacillus reuteri AJCR4: A Potential Probiotic in the Fight Against Oral Candida spp. Biofilms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karczewski, J.; Poniedziałek, B.; Adamski, Z.; Rzymski, P. The Effects of the Microbiota on the Host Immune System. Autoimmunity 2014, 47, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, R.J.; Koo, H.; Hajishengallis, G. The Oral Microbiota: Dynamic Communities and Host Interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Munoz, R.; Dongari-Bagtzoglou, A. Anticandidal Activities by Lactobacillus Species: An Update on Mechanisms of Action. Front. Oral Health 2021, 2, 689382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Tomaro-Duchesneau, C.; Rodes, L.; Malhotra, M.; Tabrizian, M.; Prakash, S. Investigation of Probiotic Bacteria as Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease Biotherapeutics. Benef. Microbes 2014, 5, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Ren, B.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, L.; Xu, X. Cross-Kingdom Interaction between Candida Albicans and Oral Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 911623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, G.; Pandey, R.K.; Singh, R.K.; Pandey, N. Can Early Exposure to Probiotics in Children Prevent Dental Caries? A Current Perspective. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2012, 2, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Veerapandian, R.; Paudyal, A.; Schneider, S.M.; Lee, S.T.M.; Vediyappan, G. A Mouse Model of Immunosuppression Facilitates Oral Candida Albicans Biofilms, Bacterial Dysbiosis and Dissemination of Infection. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1467896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seminario-Amez, M.; López-López, J.; Estrugo-Devesa, A.; Ayuso-Montero, R.; Jané-Salas, E. Probiotics and Oral Health: A Systematic Review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Y Cir. Bucal 2017, 22, e282–e288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, R.E. Probiotics for Oral Health: A Critical Evaluation of Bacterial Strains. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1430810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S. Suppression of Streptococcus Mutans and Candida Albicans by Probiotics:An In Vitro Study. Dentistry 2012, 2, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, V.; Hiscock, H.; Tang, M.L.K.; Mensah, F.K.; Nation, M.L.; Satzke, C.; Heine, R.G.; Stock, A.; Barr, R.G.; Wake, M. Treating Infant Colic with the Probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri: Double Blind, Placebo Controlled Randomised Trial. BMJ 2014, 348, g2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaza-Diaz, J.; Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J.; Gil-Campos, M.; Gil, A. Mechanisms of Action of Probiotics. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10 (Suppl 1), S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’errico, G.; Bianco, E.; Tregambi, E.; Maddalone, M. Usage of Lactobacillus reuteri Dsm 17938 and Atcc Pta 5289 in the Treatment of the Patient with Black Stains. World J. Dent. 2021, 12, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxelin, M.; Tynkkynen, S.; Mattila-Sandholm, T.; De Vos, W.M. Probiotic and Other Functional Microbes: From Markets to Mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2005, 16, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaker, R.P.; Stephen, A.S. Use of Probiotics and Oral Health. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2017, 4, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzini, B.; Pizzo, G.; Scapagnini, G.; Nuzzo, D.; Vasto, S. Probiotics and oral health. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012, 18, 5522–5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossoni, R.D.; de Barros, P.P.; de Alvarenga, J.A.; Ribeiro, F.d.C.; Velloso, M.d.S.; Fuchs, B.B.; Mylonakis, E.; Jorge, A.O.C.; Junqueira, J.C. Antifungal Activity of Clinical Lactobacillus Strains against Candida albicans Biofilms: Identification of Potential Probiotic Candidates to Prevent Oral Candidiasis. Biofouling 2018, 34, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maccelli, A.; Carradori, S.; Puca, V.; Sisto, F.; Lanuti, P.; Crestoni, M.E.; Lasalvia, A.; Muraro, R.; Bysell, H.; Sotto, A.D.; et al. Correlation between the Antimicrobial Activity and Metabolic Profiles of Cell Free Supernatants and Membrane Vesicles Produced by Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.C.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, A.; Černáková, L.; Rodrigues, C.F. Application of Probiotics in Candidiasis Management. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 8249–8264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, Q.; Tavella, V.J.; Luo, X.M. Role of Lactobacillus reuteri in Human Health and Diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinacci, B.; Pellegrini, B.; Roos, S. A Mini-Review: Valuable Allies for Human Health: Probiotic Strains of Limosilactobacillus Reuteri. Ital. J. Anat. Embryol. 2023, 127, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoudi, N.M.; Almabadi, E.S.; El Ashiry, E.A.; El Derwi, D.A. Effect of Probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri on Salivary Cariogenic Bacterial Counts among Groups of Preschool Children in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2018, 42, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, V.P.; Dhillon, J.K. Dental Caries: A Disease Which Needs Attention. Indian. J. Pediatr. 2018, 85, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Jia, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.J.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, L. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Caries in Primary Teeth from 1990 to 2021: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, R.B.; Menegazzo, G.R.; Knorst, J.K.; Ardenghi, T.M. Availability of Public Dental Care Service and Dental Caries Increment in Children: A Cohort Study. J. Public Health Dent. 2021, 81, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perinetti, G.; Caputi, S.; Varvara, G. Risk/Prevention Indicators for the Prevalence of Dental Caries in Schoolchildren: Results from the Italian OHSAR Survey. Caries Res. 2005, 39, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, T.; Worthington, H.V.; Glenny, A.M.; Marinho, V.C.C.; Jeroncic, A. Fluoride Toothpastes of Different Concentrations for Preventing Dental Caries. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, P.D. Are Dental Diseases Examples of Ecological Catastrophes? Microbiology 2003, 149 Pt 2, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twetman, S.; Jørgensen, M.R. Can Probiotic Supplements Prevent Early Childhood Caries? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Benef. Microbes 2021, 12, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Devine, D.A.; Vernon, J.J. Manipulating the Diseased Oral Microbiome: The Power of Probiotics and Prebiotics. J. Oral. Microbiol. 2024, 16, 2307416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufanaru, C.; Munn, Z.; Aromataris, E.; Campbell, J.; Hopp, L. Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gizani, S.; Petsi, G.; Twetman, S.; Caroni, C.; Makou, M.; Papagianoulis, L. Effect of the Probiotic Bacterium Lactobacillus reuteri on White Spot Lesion Development in Orthodontic Patients. Eur. J. Orthod. 2016, 38, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasslöf, P.; Granqvist, L.; Stecksén-Blicks, C.; Twetman, S. Prevention of Recurrent Childhood Caries with Probiotic Supplements: A Randomized Controlled Trial with a 12-Month Follow-Up. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2022, 14, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, M.K.; Larsen, I.N.; Karlsson, L.; Twetman, S. Effect of Tablets Containing Probiotic Bacteria (Lactobacillus reuteri) on Early Caries Lesions in Adolescents: A Pilot Study. Benef. Microbes 2014, 5, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolla, V.L.; Reddy, M.S.; Srinivas, N.; Reddy, C.S.; Koppolu, P. Investigation and Comparison of the Effects of Two Probiotic Bacteria, and in Reducing Mutans Streptococci Levels in the Saliva of Children. Ann. Afr. Med. 2022, 21, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cildir, S.K.; Sandalli, N.; Nazli, S.; Alp, F.; Caglar, E. A Novel Delivery System of Probiotic Drop and Its Effect on Dental Caries Risk Factors in Cleft Lip/Palate Children. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial J. 2012, 49, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, F.; Malek, S.; James, K.; Macdonald, K.; Cadieux, P.; Burton, J.; Cioffi, I.; Lévesque, C.; Gong, S.G. Effectiveness of the Lorodent Probiotic Lozenge in Reducing Plaque and Streptococcus mutans Levels in Orthodontic Patients: A Double-Blind Randomized Control Trial. Front. Oral Health 2022, 3, 884683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrell García, C.; Ribelles Llop, M.; García Esparza, M.Á.; Flichy-Fernández, A.J.; Marqués Martínez, L.; Izquierdo Fort, R. The Use of Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 and ATCC PTA 5289 on Oral Health Indexes in a School Population: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2021, 35, 20587384211031107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stensson, M.; Koch, G.; Coric, S.; Abrahamsson, T.R.; Jenmalm, M.C.; Birkhed, D.; Wendt, L.K. Oral Administration of Lactobacillus reuteri during the First Year of Life Reduces Caries Prevalence in the Primary Dentition at 9 Years of Age. Caries Res. 2014, 48, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Nekkanti, S.; Madiyal, M.; Choudhary, P. Effect of Chewing Gums Containing Probiotics and Xylitol on Oral Health in Children: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Int. Oral Health 2018, 10, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, M.; Akhlaghi, N.; Talebian, L.; Emami, J.; Keyhani, S. Effects of Probiotic Drop Containing Lactobacillus Rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium Infantis, and Lactobacillus reuteri on Salivary Streptococcus Mutans and Lactobacillus Levels. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2016, 7, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alforaidi, S.; Bresin, A.; Almosa, N.; Lehrkinder, A.; Lingström, P. Effect of Drops Containing Lactobacillus reuteri (DSM 17938 and ATCC PTA 5289) on Plaque Acidogenicity and Other Caries-Related Variables in Orthodontic Patients. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, P.D.; Zaura, E. Dental biofilm: Ecological interactions in health and disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44 (Suppl. S18), S12–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolenbrander, P.E.; Palmer, R.J.; Rickard, A.H.; Jakubovics, N.S.; Chalmers, N.I.; Diaz, P.I. Bacterial Interactions and Successions during Plaque Development. Periodontol. 2000 2006, 42, 47–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meurman, J.H.; Stamatova, I. Probiotics: Contributions to Oral Health. Oral Dis. 2007, 13, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccari, R.; Ryffel, B.; Mazziotta, C.; Tognon, M.; Martini, F.; Torreggiani, E.; Rotondo, J.C. Probiotics Mechanism of Action on Immune Cells and Beneficial Effects on Human Health. Cells 2023, 12, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, J. Ecological Role of Lactobacilli in the Gastrointestinal Tract: Implications for Fundamental and Biomedical Research. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agossa, K.; Dubar, M.; Lemaire, G.; Blaizot, A.; Catteau, C.; Bocquet, E.; Nawrocki, L.; Boyer, E.; Meuric, V.; Siepmann, F. Effect of Lactobacillus reuteri on Gingival Inflammation and Composition of the Oral Microbiota in Patients Undergoing Treatment with Fixed Orthodontic Appliances: Study Protocol of a Randomized Control Trial. Pathogens 2022, 11, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doron, S.; Snydman, D.R. Risk and Safety of Probiotics. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60 (Suppl. S2), S129–S134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawistowska-Rojek, A.; Tyski, S. Are Probiotic Really Safe for Humans? Pol. J. Microbiol. 2018, 67, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufekci, E.; Dixon, J.S.; Gunsolley, J.C.; Lindauer, S.J. Prevalence of White Spot Lesions during Orthodontic Treatment with Fixed Appliances. Angle Orthod. 2011, 81, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, T.; Carvalho, J.P. Three-Dimensional Comparison of CBCT and Intraoral Scans for Assessing Orthodontic Traction of Impacted Canines with Clear Aligners. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azaripour, A.; Weusmann, J.; Mahmoodi, B.; Peppas, D.; Gerhold-Ay, A.; Van Noorden, C.J.F.; Willershausen, B. Braces versus Invisalign®: Gingival Parameters and Patients’ Satisfaction during Treatment: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Oral Health 2015, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundstrom, F.; Krasse, B. Streptococcus Mutans and Lactobacilli Frequency in Orthodontic Patients; the Effect of Chlorhexidine Treatments. Eur. J. Orthod. 1987, 9, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butera, A.; Folini, E.; Cosola, S.; Russo, G.; Scribante, A.; Gallo, S.; Stablum, G.; Menchini Fabris, G.B.; Covani, U.; Genovesi, A. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Probiotics Domiciliary Protocols for the Management of Periodontal Disease, in Adjunction of Non-Surgical Periodontal Therapy (NSPT): A Systematic Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, C.L.; Gerlach, R.G.; Weider, M.; Wölfel, T.; Schwarz, V.; Ströbel, A.; Schmetzer, H.; Bogdan, C.; Gölz, L. Influence of Probiotics on the Periodontium, the Oral Microbiota and the Immune Response during Orthodontic Treatment in Adolescent and Adult Patients (ProMB Trial): Study Protocol for a Prospective, Double-Blind, Controlled, Randomized Clinical Trial. BMC Oral. Health 2022, 22, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| P | Children and adolescents under 18 years old |

| I | Oral administration of L. reuteri in any formulation (drops, lozenges, tablets, chewing gum, or curds) |

| C | Placebo or no-probiotic control group |

| O | Reduction in S. mutans, improvement in plaque and gingival indices, caries prevention/reduction, changes in salivary pH or buffering, oral microbial diversity, and gingival inflammation/bleeding. |

| S | Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) |

| Databases | Advanced Research | Articles |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (((children[MeSH Terms]) AND (oral health[MeSH Terms]) OR (“saliva”[MeSH Terms]) AND (lactobacillus reuteri[MeSH Terms])) AND (probiotics[MeSH Terms])) OR ((lactobacillus reuteri[MeSH Terms]) AND (“child”[MeSH Terms]) AND (probiotics[MeSH Terms])) | 77 |

| Wiley Library | children AND oral health AND lactobacillus reuteri AND probiotics | 714 |

| Cochrane Library | children AND oral health AND lactobacillus reuteri AND probiotics | 17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carvalho, J.P.; Grondin, R.; Rompante, P.; Rodrigues, C.F.; Andrade, J.C.; Rajão, A. Limosilactobacillus reuteri in Pediatric Oral Health: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11783. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111783

Carvalho JP, Grondin R, Rompante P, Rodrigues CF, Andrade JC, Rajão A. Limosilactobacillus reuteri in Pediatric Oral Health: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11783. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111783

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarvalho, João Pedro, Romy Grondin, Paulo Rompante, Célia Fortuna Rodrigues, José Carlos Andrade, and António Rajão. 2025. "Limosilactobacillus reuteri in Pediatric Oral Health: A Systematic Review" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11783. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111783

APA StyleCarvalho, J. P., Grondin, R., Rompante, P., Rodrigues, C. F., Andrade, J. C., & Rajão, A. (2025). Limosilactobacillus reuteri in Pediatric Oral Health: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11783. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111783