Abstract

The component composition of Bulgarian essential oil from Origanum heracleoticum L. was determined by gas chromatography and mass spectrometry analysis. Fifty-three different compounds were identified in the essential oil, with carvacrol (70.31–70.52%) and p-cymene (10.86–11.03%) determined to be the main components. The antimicrobial activity of the essential oil was determined against 138 clinical isolates of four species of Candida spp., and it was found to exhibit high antimycotic activity (minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) between 64 μg mL−1 and 128 μg mL−1) against both fluconazole-sensitive and fluconazole-resistant strains. It was found that Bulgarian essential oil from O. heracleoticum L. disrupts the normal permeability of the cell membrane and inhibits some of the main virulence factors of medically important fungi in the genus Candida by preventing germination, transition to the filamentous stage of growth and the production of hydrolytic enzymes.

1. Introduction

Invasive mycoses are a growing challenge for public health due to difficult diagnosis, limited therapeutic options and increasing drug resistance. The risk is particularly high in patients with immunosuppression, oncological treatment, transplantation and prolonged intensive care, as well as in premature infants. With the publication of the WHO Fungal Priority Pathogens List (FPPL), the World Health Organization has prioritized 19 fungal pathogens with a high public health risk [1,2]. In this clinical setting, Candida spp. is among the leading causes of invasive fungal infections and is often isolated in bloodstream infections associated with vascular catheters and broad-spectrum antibiotic exposure [3,4].

Although C. albicans remains the most common causative agent, in recent years there has been a steady increase in the proportion of non-albicans Candida (NAC), including C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. pseudotropicalis, C. guilliermondii, C. krusei, C. dubliniensis, C. famata, etc. [5,6]. This alteration in the etiological spectrum holds direct clinical relevance, as NAC species frequently display elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations to azoles and exhibit unique virulence and biofilm formation characteristics [7]. Data for Bulgaria over the last 20 years confirm a similar species structure with a predominance of C. albicans, followed by NAC, while hospital series highlight a significant proportion of NAC and azole resistance [8,9,10].

The pathogenicity of Candida is determined by a set of interrelated factors. Adhesion to epithelial and inert surfaces and biofilm formation reduce sensitivity to antimycotics and phagocytic elimination [11,12,13]. Morphological plasticity facilitates tissue invasion and is a key feature of virulence, while secreted hydrolytic enzymes (aspartyl proteases, phospholipases and lipases) and the peptide toxin candidalysin contribute to barrier destruction and tissue penetration [14,15,16]. These mechanisms are critical for the clinical course and complicate therapeutic control.

The therapeutic arsenal includes azoles, polyenes, echinocandins, and allylamines, which differ in structure and mechanism of action [17,18,19]. Frequent use of azoles correlates with increasing resistance [20,21,22], and cases of echinocandin resistance have also been described [7]. Biofilm-associated tolerance further compromises efficacy and stimulates the search for anti-virulence strategies (targeting adhesion, biofilm and hyphal transformation) that reduce pathogenic potential and the risk of resistance [14,15].

Accumulating evidence indicates that Lamiaceae essential oils (EOs)—particularly oregano and thyme—act through multiple, clinically relevant mechanisms against Candida spp. [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Beyond growth inhibition, phenolic monoterpenoids such as carvacrol and thymol (dominant in Origanum spp.) disrupt plasma-membrane integrity and permeability, causing leakage and loss of function; membrane effects have been visualized/quantified and are consistent with broad antifungal activity [38,39,40,41]. Mechanistically, carvacrol and thymol also interfere with energy metabolism. These monoterpenes have been shown to stop the respiratory chain and oxidative phosphorylation, which is in line with their quick fungistatic and fungicidal effects [18]. EO constituents further target ergosterol biosynthesis—either directly (e.g., inhibition of C-24 sterol methyltransferase by plant alkaloids) or indirectly via perturbation of isoprenoid/sterol precursors—providing a rationale for ergosterol-pathway stress under EO exposure [18,39]. At sub-MIC levels, several EO molecules are anti-virulence: they block adhesion, filamentation and biofilm formation—key drivers of persistence and drug tolerance. Examples include citral, perillaldehyde and carvone (hyphal/morphogenesis blockade) and (E,E)-farnesol/(E,E)-farnesoic acid (quorum-like control of the yeast–hypha switch) [23,29,31,32].

In line with this, oregano EO reduces preformed Candida biofilms in vapor-phase models and potentiates azoles/polyenes in vitro, including against resistant isolates—supporting adjunctive use to lower effective doses and address azole resistance [34,42]; activity extends to species of current concern (e.g., Candida auris) [33]. Additional constituent-specific mechanisms strengthen this picture: eugenol can be bioactivated to a quinone–methide, depleting GSH and irreversibly modifying proteins, while allicin/ajoenes alkylate cysteine residues without gross membrane lysis—chemistries that help explain fungicidal outcomes and biofilm impacts [18]. Finally, EO action may extend to cell-wall biosynthesis (e.g., chitin-pathway inhibition and blocked germ-tube emergence by carvacrol/thymol-class agents), offering anti-filamentation effects at sub-MICs [18].

Bulgaria traditionally cultivates a number of Lamiaceae species industrially, which creates conditions for local development and sustainable access to plant raw materials. Origanum heracleoticum L. (“Greek/white oregano”) is a species of agronomic importance in Bulgaria, but published data on the antimycotic activity of Bulgarian essential oils from this species against clinically significant Candida isolates are scarce [43,44,45,46]. Even more limited is the information on whether such oils can modify key virulence determinants of Candida, such as adhesion, biofilm and hyphal transformation—domains that are directly related to clinical persistence and therapeutic failure [47,48,49,50].

The present study aims to “fill” this gap by evaluating the antimycotic activity of Bulgarian essential oil from O. heracleoticum and its monocomponents against clinical isolates of Candida spp., including C. albicans and representatives of NAC. In parallel, their effect on selected virulence factors of high clinical significance—extracellular hydrolytic enzymes and hyphal morphogenesis—is investigated to assess the potential of the oil not only as a direct antimycotic but also as a modulator of pathogenicity. The inclusion of clinical isolates seeks to achieve greater translational reliability in the results, whereas the analysis of individual monocomponents allows the leading active ingredients to be defined and the foundations for standardized future preparations to be laid.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Essential Oil Sample

Essential oil of O. heracleoticum L. (a commercial sample) was purchased from Vigalex Ltd., Gurkovo, Bulgaria. Pure compounds carvacrol (CAS № 499-75-2, product № W224502) and p-cymene (CAS № 99-87-6, product № W235601) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co., Vienna, Austria.

2.2. Determination of the Relative Density of the Essential Oil from O. heracleoticum L. at 20 °C

The relative density of essential oils at 20 °C is determined pycnometrically by reference method BDS ISO 279, 2001 [51] and is defined as the ratio of the mass of a given volume of essential oil at 20 °C to the mass of the same volume of distilled water at 20 °C.

2.3. Determination of the Refractive Index of Essential Oils

The refractive index of essential oils is determined refractometrically according to reference method BDS ISO 280, 1999 [52]. The refractive index is defined as the ratio of the sine of the angle of incidence to the sine of the angle of refraction of a light beam with a wavelength of 589.3 ± 0.3 nm as it passes from air into the essential oil at a constant temperature.

2.4. Determination of the Angle of Rotation of the Plane of Polarization of Essential Oils

The angle of rotation of the plane of polarization of essential oils is determined polarimetrically by the reference method BDS ISO 592, 1999 [53] and is defined as the angle that describes the plane of polarization of an optical beam with a wavelength of 589.3 ± 0.3 nm when passing through essential oil with a layer thickness of 100 mm at a temperature of 20 °C.

2.5. Determination of the Acid Number of Essential Oils

The acid number (AN) of essential oils is determined titrimetrically by the reference method ISO 1242, 2023 [54] and is defined as the milligrams of KOH (alcoholic solution with a concentration of 0.1 mol L−1) required to neutralize the free acids contained in 1 g of essential oil.

2.6. Determination of the Ester Number of Essential Oils

The ester number (EN) of essential oils is determined titrimetrically by reference method BDS ISO 709, 2003 [55] and is defined as mg KOH (alcoholic solution with a concentration of 0.5 mol L−1) required to saponify the esters contained in 1 g of essential oil.

2.7. GC Analysis

GC/FID and GC/MS analyses were carried out simultaneously using a Finnigan Thermo Quest Trace GC with a dual split/splitless injector, an FID detector and a Finnigan Automass quadrupole mass spectrometer. One inlet was connected to a 50 m × 0.25 mm × 1.0 μm SE-54 (5% diphenyl, 1% vinyl, 95% dimethylpolysiloxane) fused silica column (CS Chromatographie Service, Germany); the other injector was coupled to a 60 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm Carbowax 20M (polyethylene glycol) column (J & W Scientific, Levittown, PA, USA). The two columns were connected at the outlet with a quartz Y connector, and the combined effluents of the columns were split simultaneously to the FID and MS detectors with a short (ca. 50 cm) 0.1 mm ID fused silica restrictor column as a GC/MS interface. The carrier gas was helium 5.0 with a constant flow rate of 1.5 mL/min. The injector temperature was 230 °C, FID detector temperature was 250 °C, GC/MS interface heating was 250 °C, ion source was at 150 °C, EI mode was at 70 eV, and scan range was 40–300 amu. The following temperature program was used: 46 °C for 1 min to 100 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min; 100 °C to 230 °C at 2 °C/min; 230 °C for 13.2 min. Identification was achieved using Finnigan XCalibur 1.2 software with MS correlations through NIST, Adams essential oils [56], MassFinder and our own library. Retention indices of reference compounds and from literature data [57,58,59] were used to confirm peak data. Quantification of the compounds was achieved through peak area calculations of the FID chromatogram by internal peak area normalization.

2.8. Test Microorganisms

To evaluate the antimicrobial activity of O. heracleoticum L. essential oil and pure compounds, eighty-two strains of C. albicans (eighty-one clinical isolates and one reference strain ATCC 10231), twenty-four strains of C. parapsilosis (twenty-three clinical isolates and one reference strain, ATCC 22019), eighteen strains of C. glabrata (seventeen clinical isolates and one reference strain, ATCC 90030), and fourteen strains of C. tropicalis (thirteen clinical isolates and one reference strain NBIMCC 23) were used. The strains were obtained from the National Reference Laboratory of Mycology at the National Centre of Infectious and Parasitic Diseases, Sofia, Bulgaria, and the Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology at Paisii Hilendarski University of Plovdiv. The strains were maintained on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar with Chloramphenicol (SDA, HiMedia) at 4 °C.

2.9. Antimicrobial Testing

Antimicrobial evaluation of essential oil was conducted in accordance with the CLSI M27 Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts [60]. A stock solution was generated by diluting the essential oil sample with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich, Co., CAS No. 76-68-5, product No. 472301). Serial two-fold dilutions of the stock solution were conducted in RPMI 1640 broth medium, buffered to pH 7.0 with 0.165 mol L−1 MOPS buffer (3-N-morpholinopropanesulfonic acid, Sigma-Aldrich, Co., CAS No. 1132-61-2, product No. M3183), achieving final oil concentrations from 2048 µg mL−1 to 1 µg mL−1. The final concentration of DMSO did not surpass 2%. Control samples of inoculated broth medium, both with and without solvent, were incubated under identical conditions. Each well was inoculated with 0.1 mL of inoculum (0.5 × 103–2.5 × 103 cfu mL−1), in accordance with CLSI M27. Following 48 h of incubation at 35 °C, microbial growth was assessed visually, and the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) was established. The MIC was established as the minimal concentration at which complete inhibition of microbiological growth was observed. The MIC was reported as the mean value of the MICs identified for the individual strains within the species. The MICs of Fluconazole (FLC), Itraconazole (IT), and Ketoconazole (KT) were also assessed using the HiComb™ MIC Test (HiMedia), in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. To ascertain the Minimal Fungicidal Concentration (MFC) of the essential oil, 0.1 mL of each dilution exhibiting no growth was spread plated on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar with Chloramphenicol (SDA, HiMedia). The inoculated Petri dishes were incubated at 35 °C for 48 h. The colony-forming units were enumerated and compared with control plates. The Minimum Fungicidal Concentration (MFC) was established as the lowest concentration that eradicated over 99.9% of the initial inoculum. The MFC was reported as the mean value of the MFCs identified for the individual strains within the species.

2.10. Time-Kill Assay of Clinical Candida spp. with O. heracleoticum Essential Oil

A standardized inoculum is used to determine the time of death under the influence of essential oil. For this purpose, 30 mL of SDB is placed in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask, inoculated with one inoculum of a 24 h microbial culture of the respective yeast species, developed on slanted SDA agar. The samples are cultured at 35 °C, 120 rpm for 18 h on a laboratory rotary shaker. The yeast cells are separated from the culture medium by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 15 min. After removing the supernatant, the biomass is washed twice with 5 mL of sterile distilled water to remove residues from the culture medium. The washed cell pellet is suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, with the following composition (in g L−1): NaCl—8; KCl—0.2; Na2HPO4·2H2O—1.44; and KH2PO4—0.24. The cell concentration in the inoculum is fixed to a McFarland standard of 0.5 using a densitometer (DEN-1 McFarland Densitometer, Grant Instruments Ltd., UK). The optical density of the standardized inoculum corresponds to 1.106 ÷ 5.106 cfu mL−1, and the concentration of live cells in it is checked by counting the grown single colonies in the Petri dish with SDA.

A solution of the essential oil is prepared in 2% (v/v) DMSO at a concentration twice as high as the desired one. A total of 1 mL of the working solution was added to 1 mL of the standardized inoculum to obtain final oil concentrations equal to 100, 50 and 25% of the established MIC. In parallel, under the same conditions, controls both with and without DMSO are tested. Cultivation is carried out at 35 °C and 120 rpm for 18 h on a laboratory rotary shaker. At 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 h of the process, the number of viable cells was determined. For this purpose, 100 μL samples are taken, which, after appropriate dilution, are seeded by spread plating on SDA and incubated under optimal conditions for culture growth. The number of viable cells is calculated based on the single colonies grown in the Petri dish.

2.11. Methylene Blue Absorption Test

The test is performed by preparing a working solution of the essential oil under investigation in 2% (v/v) DMSO at a concentration twice as high as the desired one. To 1 mL of standardized inoculum obtained as described above, 1 mL of the working solution is added to obtain final oil concentrations equal to 100, 50 and 25% of the established MIC. In parallel, under the same conditions, a control without essential oil and controls both with and without DMSO are tested. The samples are homogenized and cultured under the conditions described above. At 0, 2, 4, 6 and 8 h, samples of 80 µL are taken, to which 20 µL of 0.05% (w/v) methylene blue solution is added. They are homogenized on a Vortex for 3 min, after which they are left to rest for 5 min at room temperature. Native preparations are made from the samples treated in this way and examined under a microscope (Olympus CX 21). In at least 10 different fields of view containing about 100 cells, those stained blue are selected, and their percentage is calculated.

2.12. Test for the Release of Cellular Substances with an Absorption Maximum at 260 nm

A working solution of the essential oil is prepared in 2% (v/v) DMSO at a concentration twice as high as the desired one. A total of 5 mL of the working solution is added to 5 mL of standardized inoculum so as to obtain final concentrations of the oil and the pure component equal to 100, 50 and 25% of the established MIC. In parallel, under the same conditions, a control without essential oil and controls both with and without DMSO are tested. The samples are homogenized and cultured under the conditions described above. At 0, 1, 2, 4, 6 and 8 h, 500 μL of each sample is taken and added to 4.5 mL of PBS. They are filtered through a membrane with a pore diameter of 0.45 μm, and the light absorption of the filtrates is measured at a wavelength of 260 nm (CAMSPEC, UK).

2.13. Test for Inhibition of Germination and Filamentous Growth of Clinical Isolates

This test is performed as described by Pozzatti et al. [61], following the procedure described for determining the antimycotic activity of essential oil by dilution in a liquid medium. N-acetylglucosamine medium (NAG) with the following composition (in g L−1) is used instead of RPMI 1640: N-acetylglucosamine—0.221; yeast extract—3.35; Na2HPO4—1.62; and K2HPO4—4.6. Then, essential oil at a concentration of 50% and 25% of MIC is added, followed by cultivation for 3 h. Appropriate dilutions are prepared, and microscopic slides are made. In at least 10 different fields of view containing about 100 cells, the cells that have formed germination tubes are selected (Olympus CX 21). The result is presented as a percentage of the total number of cells in the field of view. The percentage of germination inhibition in the test sample is calculated relative to the control of cells not treated with essential oil.

2.14. Inhibition of the Production of Extracellular Hydrolytic Enzymes by Clinical Isolates of Candida spp. Under the Action of Essential Oil from O. heracleoticum L.

2.14.1. Inhibition of Protease Production

The ability of clinical isolates of the genus Candida to hydrolyze casein in the presence and absence of essential oil is assessed on milk agar medium with the following composition (g L−1): sterile skimmed fresh milk mixed with meat–peptone broth cooled to 50 °C containing 2.5% agar, in a ratio of 1:1. The medium is supplemented with an amount of the starting working solution of the essential oil in 2% (v/v) DMSO to ensure final concentrations of the oil and the pure component in the medium equal to 50 and 25% of the established MIC. A control is prepared by adding no essential oil or DMSO to the milk agar. The prepared sterile medium is poured into Petri dishes, and, after solidification, spot inoculation is carried out with the test cultures. The Petri dishes are incubated at a temperature of 35 ± 2 °C for 72 h in a thermostat. The proteolytic activity of the strains is proportional to the diameter of the hydrolysis zones formed around the yeast colonies. To eliminate the influence of colony size, a coefficient k1 is introduced, which represents the ratio between the diameter of the hydrolysis zone (dh, mm) and the diameter of the colony (dc, mm).

2.14.2. Inhibition of Lipase Production

The ability of clinical isolates of the genus Candida to hydrolyze tributyrin in the presence and absence of essential oil is determined on tributyrin agar medium with the following composition (g L−1): peptone—5.0; yeast extract—3.0; tributyrin—10.0; agar–agar—15.0; pH: 7.2 at 25 °C. An amount of essential oil from a 2% (v/v) DMSO working solution is added to the medium to ensure final concentrations of the oil and the pure component in the medium equal to 50% and 25% of the established MIC. A control is prepared by adding no essential oil and DMSO to the tributyrin agar. The prepared medium is poured into Petri dishes, and, after solidification, spot inoculation is carried out with the test cultures. The Petri dishes are incubated at a temperature of 35 ± 2 °C for 48 h in a thermostat. The lipolytic activity of the strains is proportional to the diameter of the hydrolysis zones formed around the yeast colonies. To eliminate the influence of colony size, a coefficient k2 is introduced, which represents the ratio between the diameter of the hydrolysis zone (dh, mm) and the diameter of the colony (dc, mm).

3. Results and Discussion

Essential oils from medicinal and aromatic plants could be an alternative to classic antimycotics, but this requires in-depth research, both on their composition and on their inhibitory activity. The biological activity of essential oils, in particular their antimicrobial activity, depends mainly on their chemical composition. The content of biologically active substances in essential oils varies widely, even for the same plant species, depending on a number of genetic, geographical, agrometeorological and technological factors. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the chemical composition of essential oils is necessary to study their mechanisms of antimycotic action. The subject of this study is Bulgarian essential oil from O. heracleoticum L., as white oregano is a relatively less studied and less common oil-bearing crop in Bulgaria. Table 1 presents the results obtained for the composition of the studied essential oil from white oregano.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of essential oil from O. heracleoticum L.

The data in Table 1 show that almost the same number of compounds were identified on both types of columns used—52 on the SE-54 column and 53 on the CW20M column, accounting for 97% of the total oil composition. The main components in the composition of the essential oil are carvacrol 70.31–70.52% and p-cymene 10.86–11.03%. Baycheva and Dobreva [44] studied the composition of essential oils from wild and cultivated O. heracleoticum L. from Bulgaria and identified between 31 and 46 components in the oils, with carvacrol (57.52–75.29%) and p-cymene (7.79–19.10%) also dominating the composition of the oil. Using GC/FID and GC/MS, between 33 and 42 different compounds were identified in the composition of essential oils from white oregano from Serbia, Croatia, Greece, France and Italy [62,63,64,65,66], which shows that the Bulgarian essential oil studied is characterized by a more diverse chemical composition. In most of the oils studied, carvacrol and p-cymene were found to be the main components in O. heracleoticum L. oil [62,67,68], which is also characteristic of the Bulgarian oil studied. In oils from Italy, thymol and p-cymene [64,65] were identified as the main components, but no significant differences in the qualitative composition of the oil were found. The results obtained show that, at least in terms of the qualitative composition of the main components, essential oils from O. heracleoticum L. of different geographical origins do not differ significantly. This contradicts, to a certain extent, the significant intraspecific variations in the composition of the essential oil established by Shen et al. [69]. Such differences are observed in terms of the quantitative content of the main components. Figure 1 depicts the distribution of the identified compounds by group.

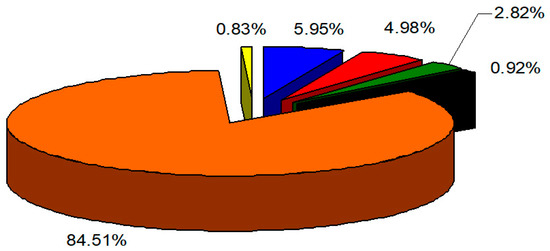

Figure 1.

Distribution of the main groups of organic compounds in the composition of essential oil from O. heracleoticum L. ●—monoterpene hydrocarbons, ●—monoterpene oxygen-containing compounds, ●—sesquiterpene hydrocarbons, ●—sesquiterpene oxygen-containing compounds, ●—phenyl propanoids, and ●—others.

The amount of phenylpropanoids in the composition of white oregano oil is very high (84.51%), followed by monoterpene hydrocarbons (5.95%), monoterpene oxygen-containing compounds (4.98%), sesquiterpene hydrocarbons (2.82%), sesquiterpene oxygen-containing compounds (0.92%) and other compounds (0.83%). The essential oil of O. heracleoticum L. is not standardized, and the main physicochemical parameters of the batch studied are as follows: d (20) 0.9581 g mL−1; n (20) 1.5113; α (20) −7; AN 3.99 mg g−1; and EN 31.84 mg g−1.

The antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of O. heracleoticum L. was determined against 138 species-identified isolates of Candida spp. The results for the antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of O. heracleoticum L. and azoles are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Antifungal activity of O. heracleoticum L. essential oil, carvacrol and azole preparations against clinical isolates of Candida species.

It was established that the essential oil of O. heracleoticum L. and carvacrol, which accounts for over 70% of its composition (Table 1), exhibit identical antimycotic activity, ranging from 58.3 µg mL−1 against the most sensitive strain of C. albicans to 170.7 µg mL−1 against the least sensitive strain of C. glabrata. No antimicrobial activity of p-cymene was observed against any of the clinical isolates tested in the specified concentration range. This, combined with the proven identical inhibitory activity of the essential oil and pure carvacrol, shows that the antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of O. heracleoticum L. is mainly due to the carvacrol in its composition. It was found that 44.2% of the isolates studied were resistant to fluconazole, distributed by species as follows: C. albicans—48.8% of isolates, C. parapsilosis—37.5% of isolates, C. glabrata—38.9% of isolates, and C. tropicalis—35.7% of isolates. It was found that white oregano essential oil exhibits antimicrobial activity against all tested strains, both fluconazole-sensitive and fluconazole-resistant, an indicator that the essential oil outperforms the tested azoles. Most of the literature data on the antimicrobial activity of O. heracleoticum L. essential oil focuses mainly on the oil’s antibacterial activity and its potential use as a natural preservative in meat products [68,70,71,72]. All authors agree on the high efficacy of the essential oil, even at low MIC values in the range of 250 µg mL−1 to 500 µg mL−1. Čabarkapa et al. [73] and Adam et al. [74] report that the oil from O. heracleoticum L. exhibits high antimicrobial activity against certain fungi and dermatophytes. There is almost no data on the inhibitory effect of white oregano essential oil against medically important fungi of the genus Candida, which makes it impossible to directly compare the results obtained with those of other authors in detail. The high antimycotic activity of Bulgarian essential oil from O. heracleoticum L. is comparable to the strong antimycotic effect proven by other researchers [36,41,50,66,75]. Our results are also confirmed by the data of Dalleau et al. [76], Marcos-Arias et al. [77], and Erfaninia et al. [78], who also found that essential oils rich in carvacrol exhibit the same activity against fluconazole-sensitive and fluconazole-resistant representatives of the Candida genus.

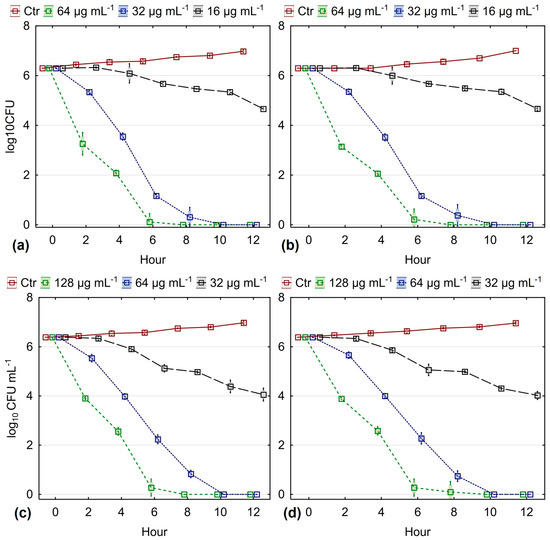

One of the criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of various antimicrobial agents is the so-called “death curve”. In order to evaluate the antimycotic activity of the essential oil under investigation, survival tests were conducted with 10 strains of the most sensitive species, C. albicans (MIC 64 µg mL−1), and 10 strains of the most resistant species, C. glabrata (MIC 128 µg mL−1), selecting both fluconazole-sensitive and fluconazole-resistant strains. The death curves for the two species studied, under the effect of essential oil from O. heracleoticum L. at a concentration equal to 25% of the MIC, 50% of the MIC, and the MIC, are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Effect of inhibitory (MIC) and subinhibitory concentrations on the survival rate of: (a) FLC-susceptible C. albicans; (b) FLC-resistant C. albicans; (c) FLC-susceptible C. glabrata; (d) FLC-resistant C. glabrata (results are presented as mean ± 0.95 conf. interval).

The data indicate that when the essential oil is used at its MIC, all cells die by the 6th hour of treatment. Reducing the concentration of white oregano essential oil to 50% of MIC increases the time until cell death by 2 h, and at a concentration of 25% of MIC, a significant decrease in the number of surviving cells is not observed until the 10th hour after treatment.

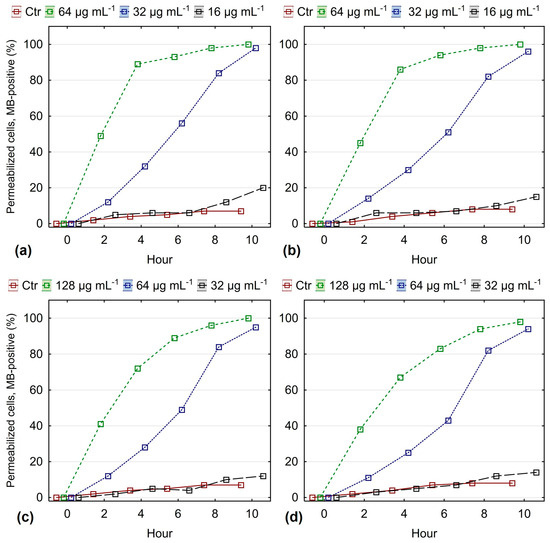

Most of the antifungals used (azoles and polyenes) disrupt the normal permeability of the cell membrane [79], albeit by different mechanisms. When studying the effect of different compounds on membrane permeability, one of the most accessible and commonly used methods is to study the absorption of methylene blue or fluorescent dyes by treated and untreated cells [80,81,82]. As is well known, in a normally functioning membrane, these dyes do not enter the cytoplasm of the cells. In an attempt to clarify whether the antimicrobial activity of O. heracleoticum L. essential oil against clinical isolates of Candida spp. is based on disruption of the normal permeability of the yeast membrane, a series of experiments was conducted. The absorption of methylene blue by fluconazole-sensitive and fluconazole-resistant strains of C. albicans and C. glabrata treated with white oregano oil was monitored. The results are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Time course of membrane permeabilization under the influence of different concentrations of O. heracleoticum L. essential oil quantified by methylene blue staining: (a) FLC-susceptible C. albicans; (b) FLC-resistant C. albicans; (c) FLC-susceptible C. glabrata; (d) FLC-resistant C. glabrata (results are presented as mean ± 0.95 conf. interval).

The data presented in Figure 3 shows that the permeability of the membrane of C. albicans to methylene blue changes under the action of the essential oil. At the MIC (64 μg mL−1) of white oregano oil, 90% of the cells had absorbed the dye by the 4th hour. At a concentration of oil MIC50 (32 μg mL−1), a similar but weaker effect was observed at the 8th hour of treatment. The number of cells that absorbed methylene blue at oil concentrations equal to 25% of the MIC was almost the same as in the control samples that were not treated with essential oils. Similar results were obtained for strains of the species C. glabrata. It is impressive that, again, no difference was found in the effect of essential oils on membrane permeability in fluconazole-sensitive and fluconazole-resistant strains.

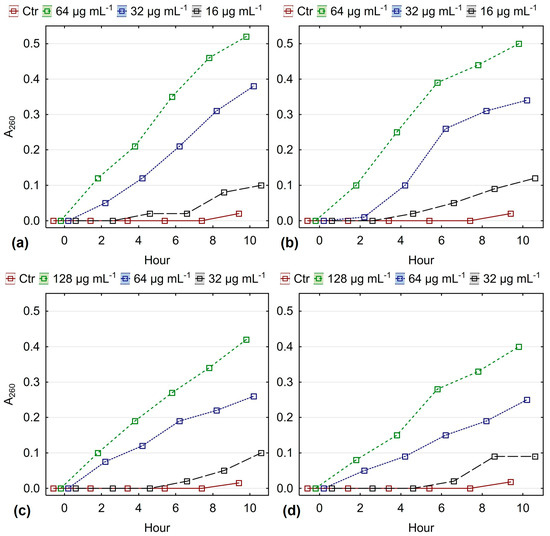

When the normal permeability of the membrane is disrupted, the cells release low-molecular-weight compounds, such as nucleotides and their components (purines, pyrimidines), amino acids, etc., which have an absorption maximum at 260 nm. An increase in A260 in cell-free filtrate from treated microbial cultures would indicate a change in the normal permeability of the membrane of medically significant fungi under the action of essential oil. Figure 4 shows the change in A260 in cell-free filtrate from fluconazole-sensitive and fluconazole-resistant strains of C. albicans and C. glabrata treated with essential oil from O. heracleoticum L.

Figure 4.

A260 (absorbance at 260 nm) in cell-free filtrates after exposure to O. heracleoticum essential oil at MIC, MIC50, and MIC25 over time: (a) FLC-susceptible C. albicans; (b) FLC-resistant C. albicans; (c) FLC-susceptible C. glabrata; (d) FLC-resistant C. glabrata (results are presented as mean ± 0.95 conf. interval).

The data show that when C. albicans isolates are treated with essential oil, values for A260 in the cell-free filtrate from the culture fluid increase. The increase is most pronounced when the culture is treated with white oregano essential oil at a concentration of 64 μg mL−1 (MIC), which causes an increase in absorbance (A260) from 0 to 0.50 in fluconazole-resistant strains and to 0.52 for fluconazole-sensitive strains. There are no significant differences in A260 values for the same treatment time interval with essential oils in resistant and sensitive strains. With a decrease in the concentration of exposure from MIC to MIC50, the effect on the change in A260, respectively, and on the permeability of the yeast membrane, decreases. At an exposure concentration of MIC25, this effect is barely observed, as the A260 values are within the range of the controls. Exposure of C. glabrata strains to essential oil from O. heracleoticum L. showed a similar trend in A260 change. No significant differences were observed in the effect of essential oils on membrane permeability in fluconazole-sensitive and fluconazole-resistant strains, which proves the more complex mechanism of antimycotic action of white oregano essential oil compared to azoles.

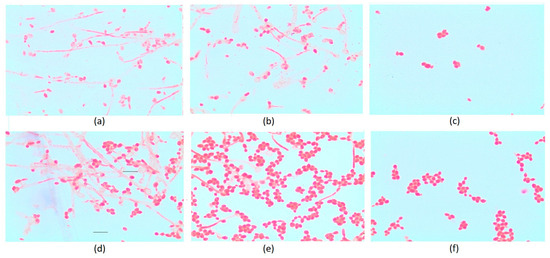

From a practical perspective, it is extremely important to determine whether essential oil from O. heracleoticum L. inhibits some of the virulence factors of medically significant yeasts. The stages of colonization and development of Candida spp. infection include the formation of germ tubes, adhesion to epithelial cells in the host organism, and transition to a filamentous stage of growth [15,34,48,83,84,85], during which dimorphic fungi produce hydrolytic enzymes. The first and most important stage in the development of candidal infections is undoubtedly the formation of germ tubes and adhesion. In this regard, researchers have investigated how essential oil from O. heracleoticum L. inhibits the formation of germination tubes and the transition from the cellular to the filamentous phase of growth in clinical isolates of Candida spp. The effect of essential oil from O. heracleoticum L. on germination was determined at concentrations of white oregano oil equal to MIC50 and MIC25, treating only fluconazole-resistant strains of the two species, C. albicans and C. glabrata. The results obtained are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Effect of white oregano essential oil on the formation of germination tubes and the transition to the filamentous stage: (a) C. albicans control without essential oil; (b) C. albicans treated with MIC25; (c) C. albicans treated with MIC50; (d) C. glabrata control without essential oil; (e) C. glabrata treated with MIC25; (f) C. glabrata treated with MIC50.

The data from the experiment show that essential oil from O. heracleoticum L. inhibits the formation of germination tubes and the transition to the filamentous stage of development in both yeast species studied. In the control sample, which was not treated with essential oil, 82% of the cells formed germination tubes, and intensive filamentous growth was observed, while at a concentration of white oregano essential oil equal to 50% of the MIC, only 2% of the cells formed germ tubes. With a decrease in the concentration of the oils to 25% of the MIC, the degree of germination inhibition decreased from 97.5% to 61%. The anti-germination activity of white oregano essential oil is most likely due to the high content of carvacrol in the oil. Our results confirm the findings of Palmeira de Oliveira et al. [86], who found that pure carvacrol exhibits high anti-germination activity.

During the infectious process, representatives of the Candida genus produce a set of hydrolytic enzymes, mainly lipases and proteases [87,88]. The effect of white oregano essential oil on the production of lipases and proteases by isolates of fluconazole-resistant strains of C. albicans and C. glabrata in TBA and milk agar media at oil concentrations equal to 50 and 25% of the MIC was investigated. The results obtained are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Effect of essential oil from O. heracleoticum L. on the production of hydrolytic enzymes by fluconazole-resistant strains of Candida.

C. albicans strains exhibit higher lipolytic activity (k2 1.76 ± 0.02) and lower proteolytic activity (k1 1.59 ± 0.05), while those of the C. glabrata species, on the contrary, exhibit higher proteolytic (k1 1.87 ± 0.01) and lower lipolytic activity (k2 1.66 ± 0.08). With an increase in the concentration of white oregano essential oil in the medium from 16 μg mL−1 (MIC25) to 32 μg mL−1 (MIC50), the values of k1 and k2 in both studied fluconazole-resistant yeast species decreased compared to the control. The data show that the essential oil studied inhibits the production of hydrolytic enzymes by fluconazole-resistant strains of the species C. albicans and C. glabrata, with the strength of the inhibitory effect depending on the concentration of the oil in the medium. The experiments conducted show that white oregano essential oils inhibit not only the growth and development of clinical isolates of Candida spp. but also the manifestation of some of their virulence factors.

4. Conclusions

In the course of the study, it was found that Bulgarian essential oil from O. heracleoticum L. is characterized by a high content of phenylpropanoids (84.51%) with carvacrol (70.31–70.52%) as its main component. The oil exhibits very high antimicrobial activity against the studied clinical isolates of Candida spp., inhibiting the development of fluconazole-resistant strains of all studied species. Essential oil from O. heracleoticum L. exhibits a complex mechanism of antimycotic action that is based on disruption of the normal permeability of the cell membrane and inhibits some of the main virulence factors of medically significant fungi of the genus Candida by preventing germination, transitioning to the filamentous stage of growth, and producing hydrolytic enzymes. The results obtained prove that Bulgarian essential oil from O. heracleoticum L. is promising for use in the composition of antimycotic agents for local application against Candida spp., for which additional studies are needed. Future research will focus on developing formulations for topical preparations with antimycotic activity, including essential oil from O. heracleoticum L.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.G., I.I. and Y.H.; methodology, Y.H., M.G. and L.I.; software, I.I.; formal analysis, Y.H., M.G. and L.I.; investigation, Y.H., M.G., L.I. and M.H.; resources, V.G., I.I. and M.H.; data curation, V.G., I.I. and Y.H.; writing, V.G., I.I. and Y.H.; visualization, I.I., M.H.; supervision, V.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Casalini, G.; Giacomelli, A.; Antinori, S. The WHO fungal priority pathogens list: A crucial reappraisal to review the prioritisation. Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Fungal Priority Pathogens List to Guide Research, Development and Public Health Action. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060241 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- CDC. Data and Statistics on Candidemia. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/candidiasis/data-research/facts-stats/index.html (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Jenkins, E.N.; Gold, J.A.W.; Benedict, K.; Lockhart, S.R.; Berkow, E.L.; Dixon, T.; Shack, S.L.; Witt, L.S.; Harrison, L.H.; Seopaul, S.; et al. Population-Based Active Surveillance for Culture-Confirmed Candidemia—10 Sites, United States, 2017–2021. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2025, 74, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Rex, J.H.; Pappas, P.G.; Hamill, R.J.; Larsen, R.A.; Horowitz, H.W.; Powderly, W.G.; Hyslop, N.; Kauffman, C.A.; Cleary, J.; et al. Antifungal susceptibility survey of 2,000 bloodstream Candida isolates in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 3149–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posteraro, B.; Posteraro, P. Update on antifungal resistance and its clinical impact. Curr. Fungal Infect. Rep. 2013, 7, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bays, D.J.; Thompson, G.R. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantardzhiev, T. Etiological Diagnosis and Etiotropic Therapy of Mycoses; National Centre for Infectious and Parasitic Diseases: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2012; 188p, ISBN 978-954-92298-3-7. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Hitkova, H.Y.; Georgieva, D.S.; Hristova, P.M.; Marinova-Bulgaranova, T.V.; Borisov, B.K.; Popov, V.G. Antifungal susceptibility of non-albicans Candida species in a tertiary care hospital, Bulgaria. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2020, 13, e101767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitkova, H.; Georgieva, D. Species distribution and antifungal susceptibility of vaginal Candida isolates. Problems Infect. Parasit. Dis. 2024, 52, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Luo, G.; Spellberg, B.J.; Edwards, J.E., Jr.; Ibrahim, A.S. Gene overexpression/suppression analysis of candidate virulence factors of Candida albicans. Eukaryotic Cell 2008, 7, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-L.; Cheng, M.-F.; Chang, Y.-W.; Young, T.-G.; Chi, H.; Lee, S.C.; Cheung, B.M.-H.; Tseng, F.-C.; Chen, T.-C.; Ho, Y.-H.; et al. Host factors do not influence the colonization or infection by fluconazole-resistant Candida species in hospitalized patients. J. Negat. Results Biomed. 2008, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, N.; Priyadharsini, M.; Sumathi, C.S.; Balasubramanian, V.; Hemapriya, J.; Kannan, R. Virulence factors and antifungal sensitivity pattern of Candida spp. isolated from HIV and TB patients. Indian. J. Microbiol. 2011, 51, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, J.P.; Lionakis, M.S. Pathogenesis and virulence of Candida albicans. Virulence 2022, 13, 89–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talapko, J.; Juzbašić, M.; Matijević, T.; Pustijanac, E.; Bekić, S.; Kotris, I.; Škrlec, I. Candida albicans—The virulence factors and clinical manifestations. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lortal, L.; Costa-de-Oliveira, S.; Martin, R.; Richardson, J.P.; Moyes, D.L.; Hader, S.; Tucey, T.M.; Warris, A.; Hall, R.A.; Naglik, J.R. Candidalysin biology and activation of host cells. mBio 2025, 16, e00603-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghannoum, M.; Rice, L. Antifungal agents: Mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauli, A. Anticandidal low molecular compounds from higher plants with special reference to compounds from essential oils. Med. Res. Rev. 2006, 26, 223–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, S.D.; Klausner, J.D.; Krupp, K.; Reingold, A.L.; Madhivanan, P. Epidemiologic features of vulvovaginal candidiasis among reproductive-age women in India. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 2012, 859071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girmenia, C.; Tuccinardi, C.; Santilli, S.; Mondello, F.; Monaco, M.; Cassone, A.; Martino, P. In vitro activity of fluconazole and voriconazole against isolates of Candida albicans from patients with haematological malignancies. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2000, 46, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Jerez-Puebla, E.; Fernández, M.; Illnait, T.; Perurena, R.; Rodríguez, I.; Martínez, G. In vitro susceptibility of Candida spp. isolated from oral cavity of HIV/AIDS patients to itraconazole, clotrimazole and ketoconazole. Arch. Venez. Farmacol. Ter. 2012, 31, 80–84. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Mulu, A.; Kassu, A.; Anagaw, B.; Moges, B.; Gelaw, A.; Alemayehu, M.; Belyhun, Y.; Biadglegne, F.; Hurissa, Z.; Moges, F.; et al. Frequent detection of ‘azole’ resistant Candida species among late presenting AIDS patients in northwest Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalemba, D.; Kunicka, A. Antibacterial and antifungal properties of essential oils. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 813–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangarife-Castaño, V.; Correa-Royero, J.; Zapata-Londoño, B.; Durán, C.; Stanshenko, E.; Mesa-Arango, A.C. Anti-Candida albicans activity, cytotoxicity and interaction with antifungal drugs of essential oils and extracts from aromatic and medicinal plants. Infectio 2011, 15, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adwan, G.; Salmeh, Y.; Adwan, K.; Barakat, A. Assessment of antifungal activity of herbal and conventional toothpastes against clinical isolates of Candida albicans. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalhinho, S.; Costa, A.; Coelho, A.; Martins, E.; Sampaio, A. Susceptibilities of Candida albicans mouth isolates to antifungal agents, essential oils and mouth rinses. Mycopathologia 2012, 174, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lira-Mota, K.; Oliveira-Pereira, F.; Oliveira, W.; Lima, I.; Oliveira, E. Antifungal activity of Thymus vulgaris L. essential oil and its constituent phytochemicals against Rhizopus oryzae: Interaction with ergosterol. Molecules 2012, 17, 14418–14433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannas, S.; Molicotti, P.; Ruggeri, M.; Cubeddu, M.; Sanguinetti, M.; Marongiu, B.; Zanetti, S. Antimycotic activity of Myrtus communis L. towards Candida spp. from isolates. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2013, 7, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olama, Z.; Holail, H.; Makki, S. Antifungal effect of some plant oils against some oral clinical isolates of Candida albicans in Lebanese community. TOJSAT 2013, 3, 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Palmeira-de-Oliveira, A.; Silva, B.M.; Palmeira-de-Oliveira, R.; Martinez-de-Oliveira, J.; Salgueiro, L. Are plant extracts a potential therapeutic approach for genital infections? Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 2914–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharanappa, R.; Vidyasagar, G.M. Argemone mexicana L.: Plant profile, phytochemistry and pharmacology—A review. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 6, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Allizond, V.; Cavallo, L.; Roana, J.; Mandras, N.; Cuffini, A.M.; Tullio, V.; Banche, G. In vitro antifungal activity of selected essential oils against Aspergillus spp. Molecules. 2023, 28, 7259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vito, M.; Caracciolo, I.; Cudazzo, F.; Bazzano, M.; Sanguinetti, M. A new potential resource in the fight against Candida auris: Essential oils. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e04385-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.; Furtado, G.H.C.; Gimenes, F.; Caetano, M.; Magário, M.K.W.; Consolaro, M.E.L. Effect of vapor-phase oregano essential oil on biofilms of antifungal-resistant vaginal isolates of Candida species. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balef, S.S.H.; Hosseini, S.S.; Asgari, N.; Sohrabi, A.; Mortazavi, N. The inhibitory effects of carvacrol, nystatin, and their combination on oral candidiasis isolates. BMC Res. Notes 2024, 17, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A. Essential Oils against Candida auris—A Promising Approach for Antifungal Activity. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Antifungal activity of essential oils and their potential against stationary-phase Candida albicans. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potente, G.; Bonvichini, F.; Gentilomi, G.A.; Antognoni, F. Anti-Candida activity of essential oils from Lamiaceae: Focus on Mediterranean taxa. Plants 2020, 9, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpiński, T.M. Anti-Candida and antibiofilm activity of selected Lamiaceae essential oils. Front. Biosci. 2023, 28, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, G.W.; Huang, T. Essential oils as promising treatments for treating Candida albicans infections: Research progress, mechanisms, and clinical applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1400105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touati, A.; Mairi, A.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Idres, T. Essential oils for biofilm control: Mechanisms, synergies, and translational challenges. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauser, S.; Raj, N.; Ahmedi, S.; Manzoor, N. Mechanistic insight into the membrane-disrupting properties of thymol in Candida species. Microbe 2024, 2, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baycheva, S. Chemical composition of oregano essential oil (Origanum heracleoticum L.). In Proceedings of the International Conference on Technics, Technologies and Education (ICTTE), Yambol, Bulgaria, 19–20 October 2017; pp. 410–417. (In Bulgarian). [Google Scholar]

- Baycheva, S.K.; Dobreva, K.Z. Chemical composition of Bulgarian white oregano (Origanum heracleoticum L.) essential oils. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1031, 012107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baycheva, S.; Kjuchukova, R.; Stoyanchev, T.; Dobreva, K. Antimicrobial activity of Bulgarian white oregano essential oils and ethanol extracts. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2889, 080024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyuchukova, R.; Baycheva, S.; Stoyanchev, T.; Dobreva, K. Application of essential oils and ethanol extracts of Bulgarian white oregano as additives in cooked-smoked sausages. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2889, 080025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacioglu, M.; Oyardi, O.; Kirinti, A. Oregano essential oil inhibits Candida spp. biofilms. Z. Naturforsch. C. J. Biosci. 2021, 76, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cid-Chevecich, C.; Müller-Sepúlveda, A.; Jara, J.A.; López-Muñoz, R.; Santander, R.; Budini, M.; Escobar, A.; Quijada, R.; Criollo, A.; Díaz-Dosque, M.; et al. Origanum vulgare L. essential oil inhibits virulence patterns of Candida spp. and potentiates the effects of fluconazole and nystatin in vitro. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Zhuge, Y.; Li, J.; Cheng, J.; Xu, K.; et al. Carvacrol induces Candida albicans apoptosis associated with Ca2+/calcineurin pathway. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mączka, W.; Gornowicz-Porowska, J.; Nowak, G. Carvacrol—A natural phenolic compound with antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity. Molecules 2023, 28, 3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BDS ISO 279:2001; Essential Oils—Determination of Relative Density at 20 °C. Bulgarian Institute for Standardization: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2001.

- BDS ISO 280:1999; Essential Oils—Determination of Refractive Index—Comparative Method. Bulgarian Institute for Standardization: Sofia, Bulgaria, 1999.

- BDS ISO 592:2001; Essential Oils—Determination of Optical Rotation. Bulgarian Institute for Standardization: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2001.

- BDS ISO 1242:2002; Essential Oils—Determination of Acid Number. Bulgarian Institute for Standardization: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2002.

- BDS ISO 709:2003; Essential Oils—Determination of Ester Number. Bulgarian Institute for Standardization: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2003.

- Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry, 4th ed.; Allured Publishing: Carol Stream, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, W.; Shibamoto, T. Qualitative Analysis of Flavor and Fragrance Volatiles by Glass Capillary Gas Chromatography; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kondjoyan, N.; Berdagué, J.-L. A Compilation of Relative Retention Indices for the Analysis of Aromatic Compounds; Laboratoire d’Etude des Arômes: Theix, France, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Joulain, D.; König, W.A. The Atlas of Spectral Data of Sesquiterpene Hydrocarbons; E.B.-Verlag: Hamburg, Germany, 1998; 658p, ISBN 3-930826-48-8. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts, 4th ed.; CLSI standard M27; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2017; ISBN 1-56238-826-6/1-56238-827-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pozzatti, P.; Loreto, É.; Nunes, M.; Rossato, L.; Santurio, J.; Alves, S. Activities of essential oils in the inhibition of Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis germ tube formation. J. Mycol. Méd. 2010, 20, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanović, I.; Mišan, A.; Sakač, M.; Čaparkapa, I.; Šarić, B.; Matić, J.J.; Jovanov, T. Evaluation of a GC-MS method for the analysis of oregano essential oil composition. Food Process. Qual. Saf. 2009, 36, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Karamanos, A.; Sotiropoulou, D. Field studies of nitrogen application on Greek oregano (Origanum vulgare ssp. hirtum (Link) Letswaart) essential oil during two cultivation seasons. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 46, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrelli, M.; Araniti, F.; Abenavoli, M.R.; Statti, G.; Conforti, F. Potential health benefits of Origanum heracleoticum essential oil: Phytochemical and biological variability among different Calabrian populations. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2018, 13, 1183–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, E.; Giovino, A.; Carrubba, A.; How Yuen Siong, V.; Rinoldo, C.; Nina, O.; Ruberto, G. Variations of essential-oil constituents in oregano (Origanum vulgare subsp. viridulum (= O. heracleoticum)) over cultivation cycles. Plants 2020, 9, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, G.; Caputo, L.; Francolino, R.; Martino, M.; De Feo, V.; De Martino, L. Origanum heracleoticum essential oils: Chemical composition, phytotoxic and α-amylase inhibitory activities. Plants 2023, 12, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerković, I.; Mastelić, J.; Miloš, M. Impact of both the season of collection and drying on volatile constituents of Origanum vulgare L. ssp. hirtum grown wild in Croatia. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2001, 36, 593–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oussalah, M.; Caillet, S.; Saucier, L.; Lacroix, M. Antimicrobial effect of selected plant essential oils on the growth of a Pseudomonas putida strain isolated from meat. Meat Sci. 2006, 73, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Pan, M.-H.; Wu, Q.-L.; Park, C.-H.; Juliani, H.R.; Ho, C.-T.; Simon, J.E. LC-MS method for the simultaneous quantitation of the anti-inflammatory constituents in oregano (Origanum species). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 7119–7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigarida, E.; Skandamis, P.; Nychas, G. Behaviour of Listeria monocytogenes and autochthonous flora on meat stored under aerobic, vacuum and modified atmosphere packaging conditions with or without the presence of oregano essential oil at 5 °C. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 89, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oussalah, M.; Caillet, S.; Saucier, L.; Lacroix, M. Inhibitory effects of selected essential oils on the growth of four pathogenic bacteria: Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella Typhimurium, Staphylococcus aureus and Listeria monocytogenes. Food Control 2007, 18, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.L.; Tan, J.Y.W.; Liu, H.Y.; Zhou, X.H.; Xiang, X.; Wang, K.Y. Evaluation of oregano essential oil (Origanum heracleoticum L.) on growth, antioxidant effect and resistance against Aeromonas hydrophila in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Aquaculture 2009, 292, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čabarkapa, I.; Škrinjar, M.; Nemet, N.; Milovanović, I. Effect of Origanum heracleoticum L. Essential oil on food-borne Penicillium aurantiogriseum and Penicillium chrysogenum isolates. Proc. Nat. Sci. Matica Srpska Novi Sad 2011, 120, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, K.; Sivropoulou, A.; Kokkini, S.; Lanaras, T.; Arsenakis, M. Antifungal activities of Origanum vulgare subsp. hirtum, Mentha spicata, Lavandula angustifolia and Salvia fruticosa essential oils against human pathogenic fungi. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 1739–1745. [Google Scholar]

- Della Pepa, T.; Elshafie, H.S.; Capasso, R.; De Feo, V.; Camele, I.; Nazzaro, F.; Scognamiglio, M.R.; Caputo, L. Antimicrobial and phytotoxic activity of Origanum heracleoticum and O. majorana essential oils growing in Cilento (Southern Italy). Molecules 2019, 24, 2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalleau, S.; Cateau, E.; Bergès, T.; Berjeaud, J.-M.; Imbert, C. In vitro activity of terpenes against Candida biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2008, 31, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Arias, C.; Eraso, E.; Madariaga, L.; Quindós, G. In vitro activities of natural products against oral Candida isolates from denture wearers. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfaninia, M.; Alizadeh, F. Killing Kinetics of carvacrol against fluconazole-susceptible and -resistant isolates of Candida tropicalis. Med. Lab. J. 2023, 17, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifaz, A.; Tirado-Sanchez, A.; Graniel, M.; Mena, C.; Valencia, A.; Ponce-Olivera, R. The efficacy and safety of sertaconazole cream (2%) in diaper dermatitis candidiasis. Mycopathologia 2013, 175, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cox, S.D.; Mann, C.M.; Markham, J.L. the mode of antimicrobial action of the essential oil of Melaleuca alternifolia (Tea Tree Oil). J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 88, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, C.; Beney, L.; Maréchal, P.-A.; Gervais, P. The effect of osmotic pressure on the membrane fluidity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae at different physiological temperatures. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 56, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina-Vaz, C.; Rodrigues, A.G.; Sansonetty, F.; Martinez-de-Oliveira, J.; Fonseca, A.F.; Mårdh, P.-A. Antifungal activity of local anesthetics against Candida Species. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 8, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acuña, E.; Contador, R.; Pereira, M.; Aguilera, J.; Berríos, J.; Fuentes-López, M. Carvacrol-induced vacuole dysfunction and morphological consequences in nakaseomyces glabratus and Candida albicans. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preda, M.; Bumbac, R.; Dumitru, I.; Bostan, M.; Ditu, L. Pathogenesis, prophylaxis, and treatment of Candida auris. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaeitabari, A.; Dahms, T.E.S. Blocking the shikimate pathway amplifies the impact of carvacrol on Candida albicans by attenuating adhesion, hyphal and biofilm formation. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e02754-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmeira-de-Oliveira, A.; Salgueiro, L.; Palmeira-de-Oliveira, R.; Martinez-de-Oliveira, J.; Pina-Vaz, C.; Queiroz, J.A.; Rodrigues, A.G. Anti-Candida activity of essential oils. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 1292–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hube, B.; Stehr, F.; Bossenz, M.; Mazur, A.; Kretschmar, M.; Schäfer, W. secreted lipases of Candida albicans: Cloning, characterisation and expression analysis of a new gene family with at least ten members. Arch. Microbiol. 2000, 174, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Azevedo, I.Z.; Semprebom, A.M.; Baboni, F.B.; Rosa, R.T.; Machado, M.A.; Samaranayake, L.P.; Rosa, E.A. Low-virulent oral Candida albicans strains isolated from smokers. Arch. Oral Biol. 2012, 57, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).