3.1. Life Cycle Assessment Results

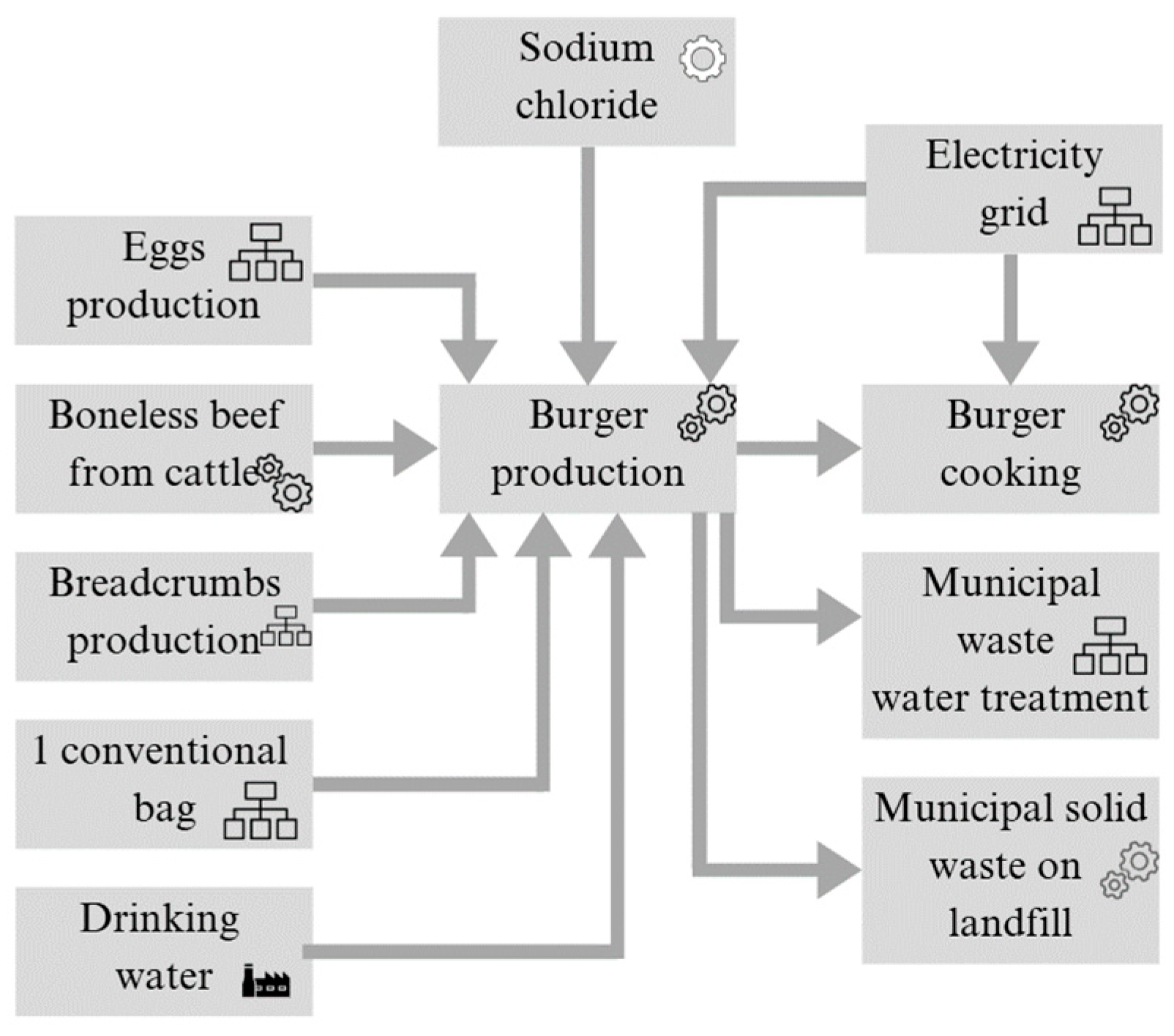

The results of the life cycle impact assessment for the production system of the conventional meat and innovative vegan burger (per 1 burger) are presented in

Table 4 for the studied impact categories [

22]. In particular, the results of the current state of the production line are presented in comparison to the results using alternative proteins from plant sources.

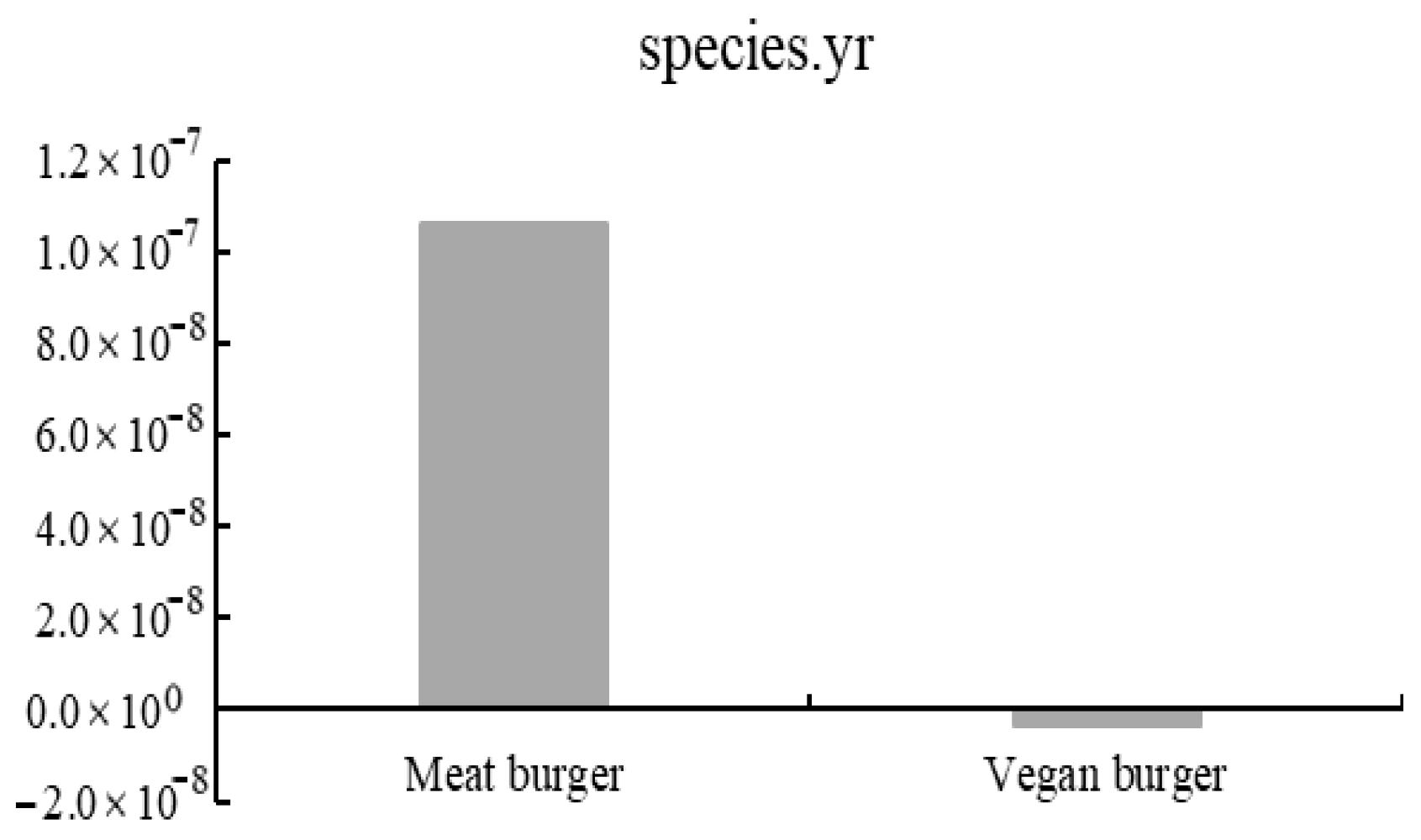

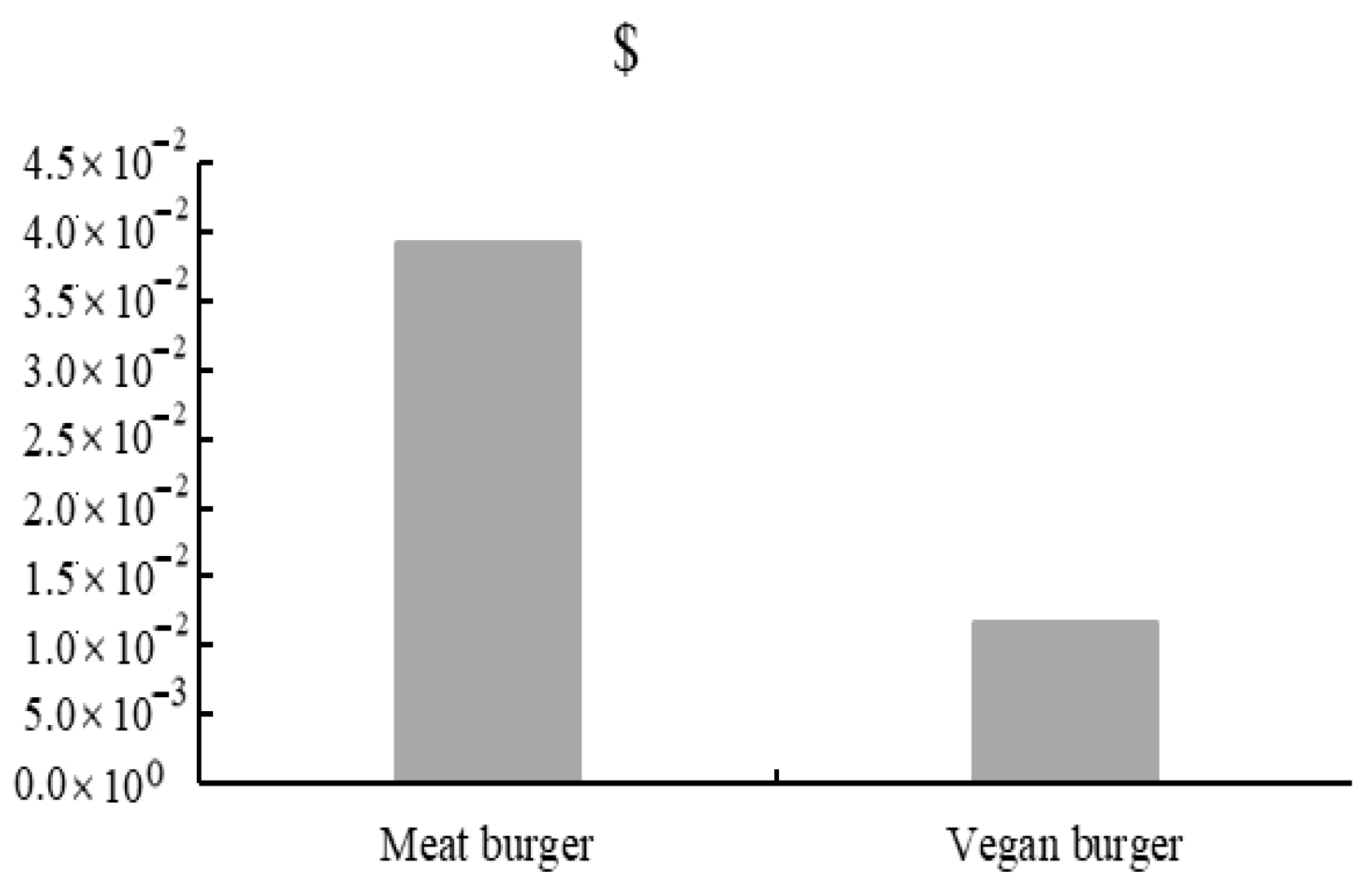

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 depict the impact on human health [DALY], ecosystems [species.yr], and resources availability [

$] of the two studied products systems that are generated for producing 1 unit of meat or vegan burger.

The findings of the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) clearly demonstrate that substituting meat with plant-based proteins in burger production substantially reduces environmental impacts across multiple categories. Furthermore, the human health burdens associated with vegan burger production are significantly lower than those of conventional meat-based burgers [

16].

Recent studies emphasize that achieving the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 °C or 2 °C above pre-industrial levels will be unattainable without significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions from the food sector [

23]. A key environmental advantage of vegan burgers is their markedly lower contribution to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Specifically, the climate change impact, expressed in kg CO

2 equivalents, is reduced by approximately 92.25% compared to meat burgers.

This substantial decrease is primarily attributed to the absence of livestock-related methane emissions and the lower energy intensity of chickpea protein processing. Additionally, chickpea cultivation acts as a carbon sink, sequestering atmospheric CO2 during plant growth, leading to net negative emissions in some impact categories. This explains values exceeding 100% reduction (e.g., −102.28%), which reflect biogenic carbon uptake.

The transition to plant-based proteins results in a 50.94% reduction in fossil fuel depletion, mainly due to lower upstream energy requirements and reduced transportation emissions associated with plant-sourced ingredients. The assessment also reveals a 99.51% decrease in fine particulate matter formation, driven by the lack of combustion and animal waste-related emissions during vegan burger production.

Contribution analysis identified key contributors to environmental impacts in the conventional system as beef production, cooking electricity, and packaging, whereas in the vegan system, the primary contributors were chickpea cultivation, NaOH used in protein extraction, and extrusion energy. Human toxicity impacts were notably lower for vegan burgers, with a complete reduction in non-cancer toxicity. This is again linked to reduced chemical inputs and absence of veterinary pharmaceuticals used in livestock production.

Impacts on aquatic ecosystems are also significantly mitigated. Freshwater eutrophication is reduced by 98.24%, while marine eutrophication decreases by 99.75% in vegan burger production, primarily due to the absence of nitrogen runoff from livestock manure and feed production. Water consumption is another crucial factor, with vegan burger production requiring 40.16% less freshwater than meat-based alternatives. Given that meat production—particularly beef—has a high water footprint, this reduction highlights the role of plant-based proteins in promoting water conservation and sustainable resource management [

24].

Land use is drastically reduced, with a 99.88% lower impact, as vegan burger production requires neither pasture grazing nor feed crop land. Although meat and dairy contribute less than 20% of global caloric intake, they occupy over 70% of all agricultural land and 40% of arable cropland [

25]. Plant-based protein production, particularly chickpeas, utilizes far less land while offering nutritional and ecological advantages.

Sensitivity analysis was qualitatively conducted by evaluating variation in key input categories (e.g., energy, transportation, extraction chemicals). However, given the standardized, optimized production procedure developed and validated through experimental trials by Hellenic Catering and NTUA, the overall system configuration was fixed. Thus, full parameter variation analysis was not included.

Methodological limitations include the exclusion of allocation due to single-product lines, expert-based uncertainty estimation (±10%), and lack of normalization or weighting as per ISO 14044 [

18,

19], given the comparative focus.

The transition from meat-based to plant-based protein sources in burger production yields substantial environmental and health benefits. The significant reductions in GHG emissions, land and water use, air pollution, and human toxicity illustrate the potential of plant-based alternatives as a sustainable solution for food production. These findings emphasize the crucial role of alternative proteins in minimizing the environmental footprint of food systems while promoting human health and resource conservation.

These results align well with recent Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) literature, which confirms the environmental superiority of plant-based alternatives. For example, Notarnicola et al. (2017) reported that replacing meat with soy or pea proteins can reduce GHG emissions by 70–90% and land use by over 85% [

26]. Similarly, a detailed LCA conducted on Beyond Burger found a 90% reduction in global warming potential, along with 93% less land use and 99% lower water consumption compared to conventional beef production [

16]. A European LCA study by Saerens et al. (2021) showed that beef burgers had a climate change impact of 22.4 kg CO

2 eq, while soy-based vegan burgers emitted only 0.6 kg CO

2 eq, highlighting dramatic reductions in ecosystem damage [

27].

While most comparative LCA studies have focused on soy and pea proteins, recent assessments have begun evaluating additional legumes. The inclusion of chickpeas in meat substitute formulations addresses both environmental and agronomic considerations and contributes to diversification in sustainable protein strategies. These findings confirm that plant-based burgers—regardless of the specific legume used—consistently achieve substantial environmental gains over traditional meat products.

3.2. Economic Results

The results for the economic evaluation of the two burgers are presented in

Table 5.

The cost analysis presented in the table highlights significant differences between the production costs of conventional meat burgers and innovative plant-based burgers. The total cost per 100 kg of meat burgers is 451.31 €, whereas the cost for the same quantity of vegan burgers is significantly lower at 214.2 €. This substantial cost reduction is also reflected in the price per individual burger, with a meat burger costing 0.66 € compared to 0.24 € for a vegan burger.

The primary reason for the cost disparity between the two products lies in the significant difference in the price of their key ingredients. Conventional burgers rely heavily on meat, which is one of the most expensive components in food production. This high cost substantially increases the overall expense of producing a traditional meat-based burger. In addition to meat, other animal-derived ingredients such as eggs also contribute to the higher production costs, making the conventional burger a more costly option.

On the other hand, the plant-based burger uses a variety of more affordable ingredients, including legumes like chickpeas and fava beans, as well as vegetables such as mushrooms and beetroot. These plant-based components are generally much less expensive than animal-derived ones. Although the vegan burger does incorporate a protein extract that is relatively costly, the overall ingredient costs remain significantly lower. The use of cost-effective plant sources helps offset the price of the more expensive components, resulting in a product that is much more economical to produce.

Both burger types have identical costs for packaging materials (2.85 €/kg), electricity during production (0.22 €/18 kWh), and water usage (0.9 €/0.3 m3). The slight variation in electricity consumption during baking is not significant, with the meat burger requiring 0.22 €/65 kWh, compared to 0.2 €/65 kWh for the vegan burger.

The waste output for both meat and vegan burger remains consistent, with liquid waste at 0.165 €/0.3 m3 and solid waste at 0.2 €/0.638 kg. These values suggest that despite the differences in raw materials and production, both burger production processes generate similar levels of waste.

Transportation costs, which are determined by diesel consumption (1.6 €/5.5 L), remain unchanged between the two products, indicating that the distribution logistics do not significantly affect the cost difference.

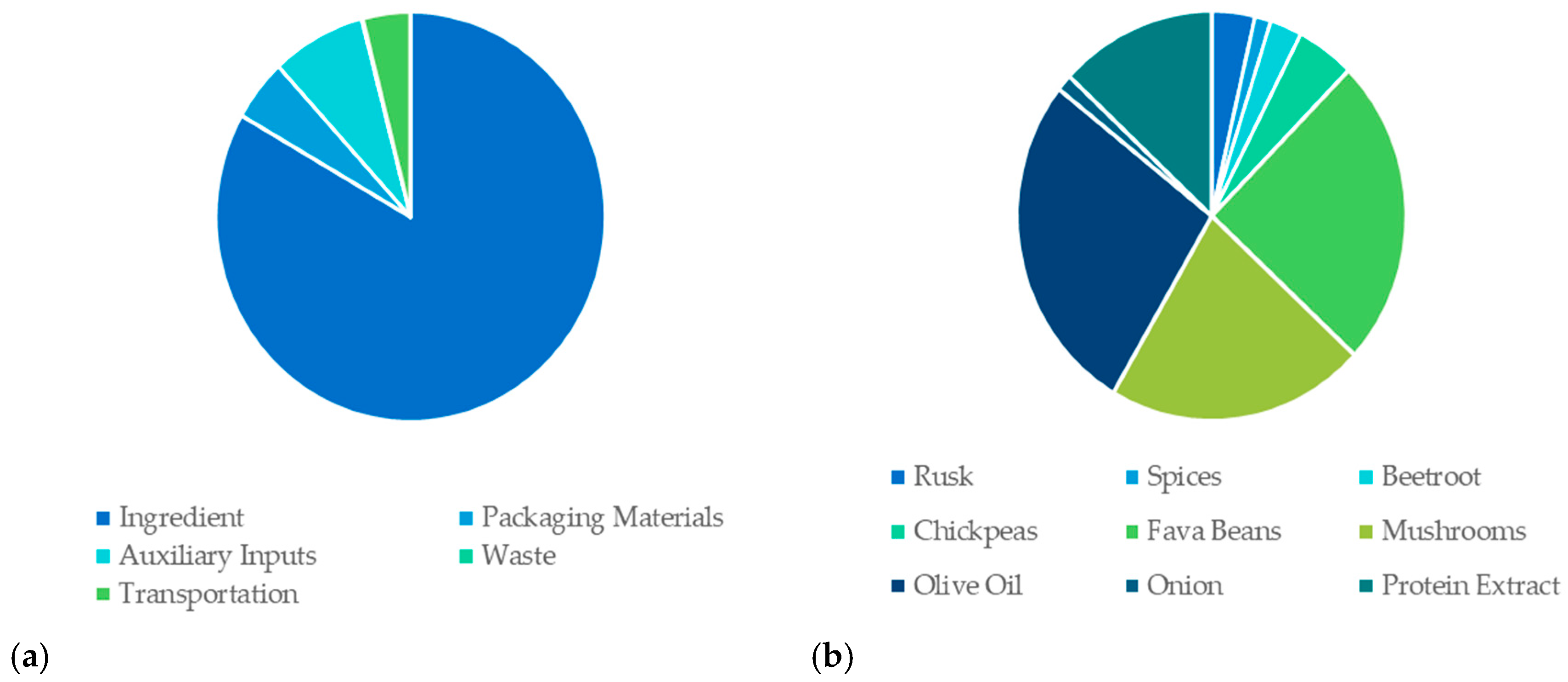

A graphical comparison of the cost structure is presented in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

Figure 8 illustrates the relative contribution of major cost categories (ingredients, packaging, auxiliary inputs, transportation, and waste) to the total cost of a meat burger.

Figure 9 details the proportional cost distribution among key ingredients, without disclosing specific quantities. This aggregated representation enables a clear understanding of the dominant cost drivers while respecting proprietary or sensitive data related to exact input formulations.

To evaluate the robustness of the economic advantage of the vegan burger, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by varying the production cost by ±20% for both burger types (

Table 6). Even in a conservative scenario where the cost of the vegan burger increases by 20% (€0.288 per unit) and the cost of the meat burger decreases by 20% (€0.528 per unit), the vegan burger remains more cost-effective by approximately €0.24 per unit. This demonstrates that the cost advantage of plant-based burger production is resilient to market fluctuations, raw material pricing, and other economic uncertainties. On a larger production scale, this differential could translate into substantial cost savings, reinforcing the financial viability of transitioning toward alternative protein-based food products.

The findings from this economic assessment suggest that innovative vegan burger production is considerably more cost-effective than traditional meat burger production. The primary cost driver for meat burgers is the increased price of animal-derived ingredients, particularly meat and eggs, whereas plant-based ingredients rely on more affordable protein sources. Despite the inclusion of the protein extract which is a high-cost, the overall production cost of the vegan burger remains significantly lower. These economic benefits, combined with the environmental advantages, make plant-based burgers a financially viable and sustainable alternative to conventional meat-based options.

3.3. Scalability and Industrial Applicability

This research highlights the potential for scaling up vegan burger production using chickpea-derived proteins in an industrial setting. The environmental and economic benefits observed suggest that these products are not only more sustainable but also offer a cost-efficient option for large-scale manufacturing. Relying on locally grown legumes with minimal processing needs strengthens regional supply chains, supports food independence, and reduces reliance on imported protein sources. Furthermore, the overall production process for vegan burgers—covering forming, packaging, and cooking—shares many similarities with traditional meat burgers, making it relatively easy to adapt existing production lines without major changes.

However, some limitations should be acknowledged. The LCA and cost analysis are based on data from a single production site, which may not fully reflect variations across different regions, technologies, or scales of operation. Moreover, certain processing steps within the production chain are resource-intensive and could present challenges when scaling up, especially in regions facing constraints in water, energy, or infrastructure. These factors highlight the need for continuous innovation and adaptation to ensure that environmental and economic benefits are maintained as production expands.

To improve the environmental profile and industrial efficiency, several strategies could be implemented. Switching to dry extraction methods for proteins could help cut down water usage and lower energy requirements. On the agricultural side, adopting more efficient practices—like precision fertilization, better crop rotations, and integrated pest control—can reduce upstream emissions and resource consumption. Using eco-friendly packaging materials, such as biodegradable or recycled-content options, would also help minimize the impact of post-consumer waste. Moreover, transitioning to renewable energy sources in both manufacturing and logistics can further reduce the carbon footprint of the entire production chain.

By pursuing these innovations, supported by appropriate policy frameworks and industry investment, plant-based burger production can become even more viable and sustainable at scale. This positions it as a promising solution for addressing future food system challenges while aligning with environmental and public health goals.