Abstract

Federated learning has emerged as a promising approach for privacy-preserving model training across decentralized UAV swarm systems. However, challenges such as data heterogeneity, communication constraints, and limited computational resources significantly hinder convergence efficiency in real-world scenarios. This work introduces a communication-aware federated learning framework that integrates multi-dimensional cost modeling with dynamic client aggregation. The proposed cost function jointly considers communication overhead, computation latency, and training contribution. A Shapley-inspired client evaluation mechanism is incorporated to guide aggregation by prioritizing high-impact participants. In addition, a two-phase training strategy is devised to balance learning accuracy and resource efficiency across different training stages. Experimental results on the MNIST and CIFAR-10 benchmark datasets under non-IID settings demonstrate that the proposed method achieves faster convergence, higher accuracy, and reduced communication-computation cost. These results highlight its suitability for deployment in bandwidth-constrained, resource-limited UAV edge environments.

1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) technologies, UAV networks have demonstrated significant potential in performing complex tasks across various application domains, including smart cities, disaster recovery, environmental monitoring, and military operations [1,2,3]. In recent years, the integration of edge computing and distributed learning within UAV networks has garnered growing attention from both academia and industry [4,5,6]. As both data collectors and edge processors, UAVs are inherently well-suited for decentralized machine learning [7]. Through collaborative operations, UAV swarms can distribute computational workloads across tasks, enabling efficient real-time data processing and autonomous decision-making in dynamic environments. UAV networks face inherent challenges in enabling efficient on-device learning. The effective deployment of such distributed intelligence in UAV networks remains challenged by system heterogeneity, intermittent connectivity [8,9], and limited communication resources [10,11,12]. These constraints are especially pronounced in energy-limited UAV environments, where factors such as CPU capacity, memory availability, and power consumption directly affect the feasibility of on-device training [13,14]. Federated Learning (FL) has emerged as a promising paradigm for collaborative model training across UAVs, allowing global model updates without exchanging raw data, thereby preserving data privacy and security. Nevertheless, existing FL methods still struggle to cope with the complex resource constraints and data heterogeneity inherent in UAV swarm systems.

Traditional FL methods struggle to scale in UAV swarm environments. The application of traditional FL methods in UAV-based scenarios remains challenging due to several inherent limitations. Specifically, data heterogeneity across UAVs leads to performance degradation and slow convergence under conventional aggregation strategies [15]. Additionally, the communication cost associated with frequent model synchronization can be prohibitively high in bandwidth-constrained aerial networks [16,17]. Moreover, device heterogeneity—including varying computational capacities and energy budgets—further complicates the coordination and scheduling of federated training tasks [18].

To address the aforementioned challenges, numerous studies have proposed diverse solutions. One of the most well-known algorithms is FedAvg [19], which constructs a global model by averaging the local models of participating clients. While effective in relatively homogeneous environments, FedAvg tends to perform poorly under non-IID data distributions, often resulting in convergence to suboptimal solutions and failing to adequately manage computational and communication heterogeneity across clients. To mitigate these issues, various extensions have been proposed. Among them, FedProx [20] introduces a proximal term in the local objective function to alleviate the divergence caused by heterogeneous data. However, FedProx still lacks explicit mechanisms to optimize communication efficiency, which is critical in bandwidth-constrained settings such as UAV networks [21]. In the con-text of UAV-based systems, researchers have explored the integration of FL with other intelligent decision-making techniques. For instance, reinforcement learning [22] has been applied for task allocation among UAVs to improve collaborative efficiency [23], while distributed optimization techniques have been used to enhance model aggregation and client selection under dynamic network conditions [24,25]. Although promising, these approaches often overlook the unique resource constraints in UAV networks, such as limited bandwidth, dynamic topologies, and variable energy budgets. In addition, Shapley value-based methods have been proposed to estimate the individual contributions of clients during training, enabling adaptive aggregation strategies. These methods offer theoretical fairness and dynamic participation adjustment. However, their application in resource-aware federated learning frameworks for UAV networks remains limited, and their practical effectiveness under real-world constraints has yet to be thoroughly validated.

In this work, we propose a communication-aware FL framework designed to overcome the inherent limitations of conventional FL methods when deployed in UAV net-works. The primary contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- We propose a UAV-enabled network model and a multi-dimensional cost function that accounts for communication, computation, and training contribution. Based on real UAV data profiles, it supports dynamic client participation to reduce resource usage while ensuring model accuracy and energy efficiency.

- To effectively solve the non-convex and tightly coupled resource allocation problem, we formulate the task assignment process as a cooperative game-theoretic decision problem. Based on this formulation, we introduce a Shapley-value-based contribution evaluation mechanism and propose a dynamic aggregation algorithm, termed TVCL (Time-Varying Collaborative Learning). The algorithm approximates near-optimal solutions to the formulated cooperative game by assigning aggregation weights based on each UAV’s marginal contribution. Furthermore, a multi-phase training strategy is introduced to adaptively respond to dynamic communication and computation conditions, thereby enhancing convergence efficiency and overall model performance.

- We conduct extensive simulations on standard bench-mark datasets, including MNIST and CIFAR-10, to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed framework under non-IID data conditions. The results demonstrate that our method significantly outperforms conventional FL approaches such as FedAvg and FedProx, achieving faster convergence and higher final accuracy, while simultaneously reducing both communication cost and computational burden.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on multi-UAV collaboration, federated learning, and cooperative game theory. Section 3 presents the proposed method, including the Shapley-based aggregation mechanism, cost modeling, and training strategy. Section 4 reports the experimental setup, results, and analysis. Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Multi-Drone Collaboration

Multi-UAV collaboration enables drones to jointly perform complex tasks through communication and coordination, extending capabilities beyond a single platform. It has demonstrated great potential in environmental monitoring, search and rescue, logistics, and disaster response due to its flexibility and scalability. However, data heterogeneity poses major challenges for resource scheduling, task allocation, and model convergence in collaborative learning. The federated learning algorithm used in the UAV field: FedAvg [19] algorithm can only handle weakly heterogeneous data and performs poorly when dealing with highly heterogeneous data. Fedopt [26] has improved communication efficiency, but still may fall into local optima when facing extreme data heterogeneity, affecting the global convergence performance. FedSgd [27] is suitable for synchronous update scenarios, but is prone to oscillation or slow convergence when dealing with highly heterogeneous data, reducing the overall training stability. UAVs can collaborate adaptively through decentralized task allocation and resource sharing, enabling efficient operation in complex environments without central coordination. To further improve scalability and robustness, we integrate federated learning and cooperative game theory to manage data heterogeneity and propose an adaptive aggregation strategy for efficient multi-UAV collaboration.

2.2. Federated Learning

Federated learning is a decentralized paradigm that enables collaborative model training across distributed devices without sharing raw data, thereby effectively preserving data privacy. However, FL faces several challenges in practical applications, including data and device heterogeneity [28], privacy protection issues [29], and communication efficiency problems [30]. Data heterogeneity denotes the statistical inconsistency across clients, where local datasets follow non-independent and non-identically distributed (non-IID) patterns. This divergence fundamentally impedes stable and efficient model convergence. FedAvg [19] is the most widely used FL algorithm, performing well in scenarios with homogeneous or simple heterogeneous data, but it performs poorly when dealing with highly non-IID data. To mitigate the adverse effects of data heterogeneity, researchers have proposed a variety of methods, mainly divided into two categories: local client training methods [31,32] and global model aggregation strategies [33]. FedBN [31] introduced an improved strategy that enables each client to retain local batch normalization parameters and avoid aggregating BN parameters during model aggregation, thereby avoiding performance degradation caused by feature distribution differences between clients. pFedMe [32] adopts the method of meta-learning to optimize the personalized part of each client, ensuring the universality of the shared layers of the global model while maximizing the performance of each client on their specific tasks. MOON [33] alleviates the non-IID (different IID) problem by introducing contrastive learning, which reduces the feature representation gap between local models and global models and also increases the distance between the representations of local models and the previous round of models. These advances highlight the ongoing maturation of federated learning in handling data heterogeneity and strengthen its potential for deployment in real-world distributed environments.

2.3. Cooperative Game

Cooperative game theory (CGT) offers a rigorous foundation for multi-agent cooperation by quantifying individual contributions through the Shapley value and enabling efficient task and resource coordination in dynamic UAV networks. In drone collaborative tasks, cooperative game theory is mainly used for resource allocation among drones [34,35] and task scheduling [36,37]. For example, the method in [34] formulates a cooperative game model to optimize energy efficiency for UAV task offloading in edge-computing networks, maximizing overall energy utility while minimizing system energy consumption. Ref. [35] introduces a coordinated dynamic task allocation scheme using a proposer–responder mechanism and priority experience replay within a multi-agent reinforcement learning framework, effectively handling environmental uncertainty and improving scalability. The approach in [36] integrates local and global utility functions into a unified game model for UAV group task allocation, ensuring system stability and operational efficiency under uncertain conditions. Finally, ref. [37] develops a decentralized task allocation algorithm that combines game-theoretic market mechanisms with ant colony optimization and k-means clustering, enhancing mobility and field coverage in autonomous UAV clusters. Existing UAV-oriented federated learning schemes largely neglect communication heterogeneity and client-specific contribution. We propose a cost-aware, communication-adaptive framework that integrates Shapley-based weighting with dynamic client selection to achieve efficient and equitable model aggregation.

3. Methods

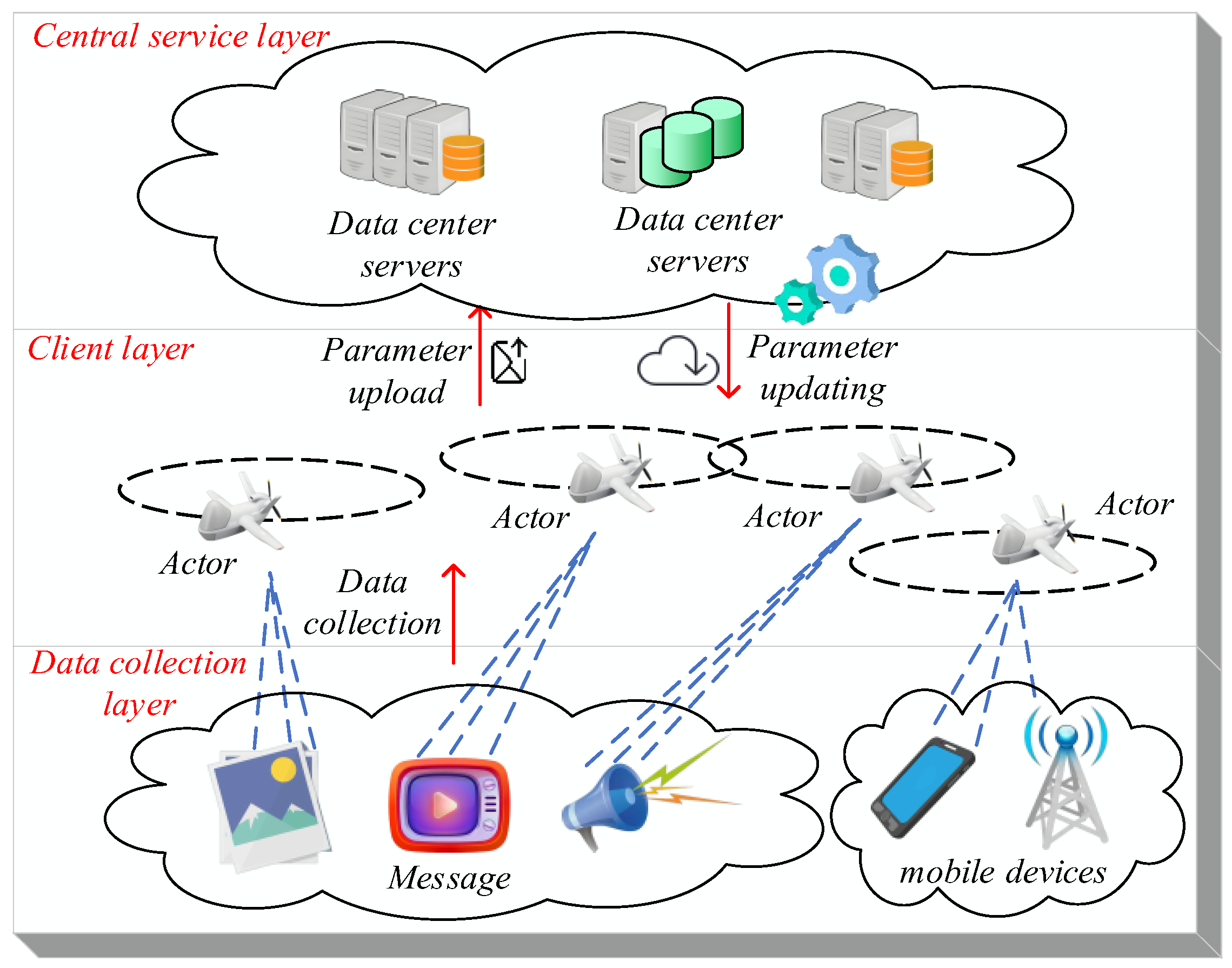

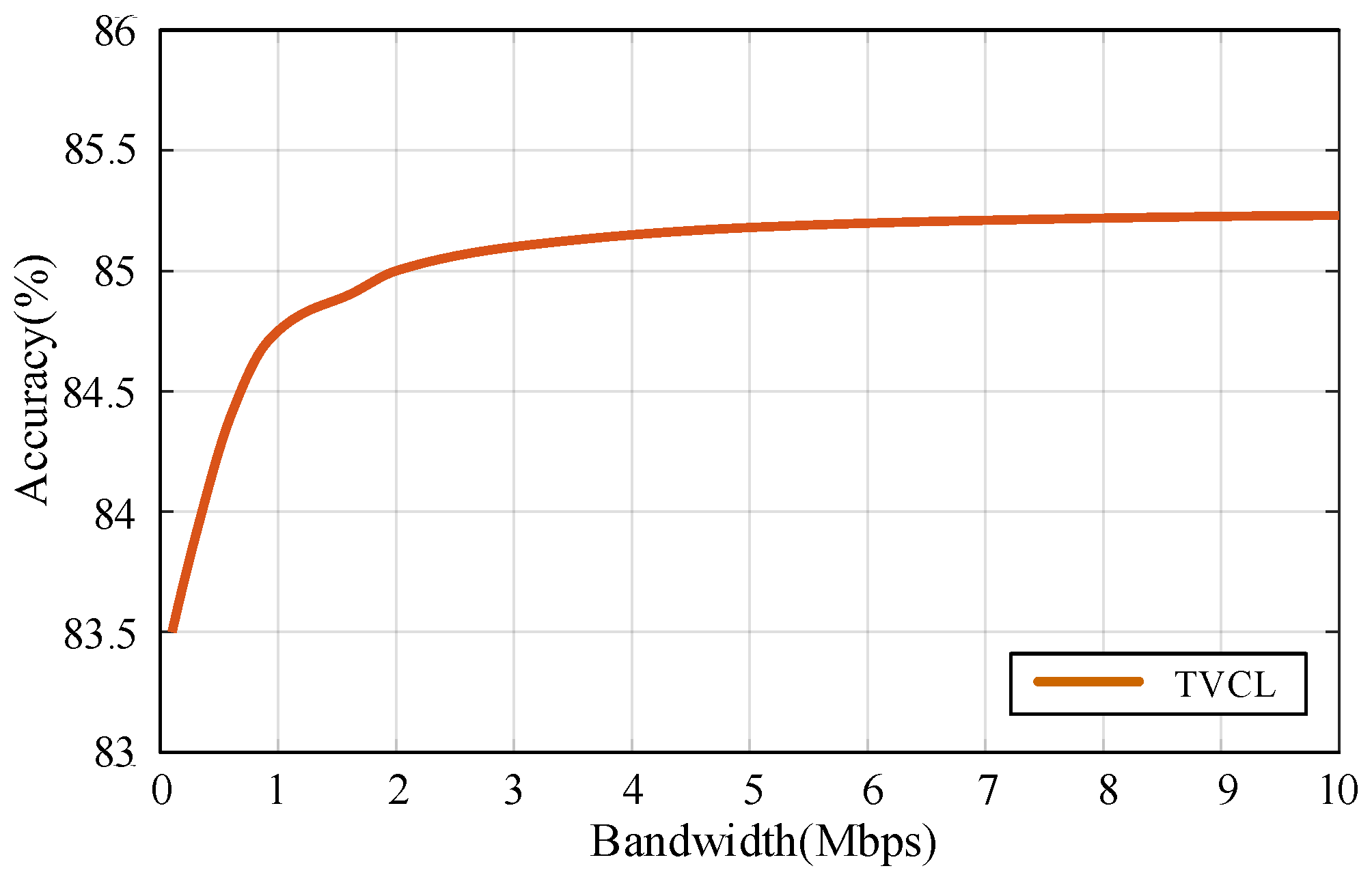

Throughout this paper, each UAV participating in the training process is referred to as a client. In general, federated learning systems can be conceptually organized into three distinct layers: the central server layer, the client layer, and the data acquisition layer. Accordingly, a three-tier federated learning architecture is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distributed machine learning data transmission process in multiple unmanned aerial systems. The orange and green cylinders denote data center servers situated in different geographic locations, and the red arrows represent inter-layer data communication flows.

As shown in Figure 1, the data acquisition layer collects large volumes of heterogeneous information such as images, audio, and video, serving as the foundation for federated learning. The device layer, composed of UAV-mounted sensors and communication modules, handles local data processing and uploads model parameters. These parameters are then aggregated at the central server layer, typically consisting of base stations responsible for coordination and model updates.

Due to variations in UAV hardware capabilities and environmental conditions, the data distribution across devices is inherently nonuniform. This results in significant heterogeneity in the data collected by different UAVs, which poses challenges to the convergence speed and stability of distributed learning algorithms. As illustrated in Figure 1, within a UAV swarm, there often exist substantial discrepancies in the target information acquired by different clients during the same time interval. These discrepancies manifest in both data type and volume, potentially causing the aggregated global model to deviate from the expected performance. To address this issue, the Shapley value is employed to evaluate the marginal contribution of each client to the training process, thereby guiding optimization of the global model’s overall performance. The Shapley value, originating from cooperative game theory, provides a principled method to fairly quantify each participant’s contribution to a collective task. In the context of federated learning, it is used to measure the individual contribution of each client during model training. Based on these values, computational resources can be dynamically allocated, aiming to improve the final performance of the global model and better align it with learning objectives.

The key notations are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Notations.

3.1. Shapley-Based Aggregation with Contribution-Aware Weighting

In federated learning, the Shapley value quantifies each client’s contribution by measuring its impact on the global model across all possible client subsets. It computes marginal contributions to enable fine-grained and fair evaluation, ensuring that each client’s influence is fully captured beyond static or single-instance assessments.

During local training, each client updates its model using a cross-entropy loss. After each communication round, the Shapley value is estimated based on the change in local loss, allowing aggregation weights to reflect each client’s contribution.

During training, some clients may provide more valuable data due to differences in data quality, computation, communication, or location. These variations are captured by Shapley values, which reflect each client’s marginal contribution. Incorporating these values into global aggregation assigns greater weights to more impactful UAVs, improving overall learning efficiency. The detailed procedure for estimating the client contribution based on the Shapley value is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Shapley Estimation. |

| Input: local models {θk}, global model θ, validation set D_val, number of Monte Carlo samples S Output: Normalized Shapley values {φk} Initialize φk ← 0 for all k for s = 1 to S do Randomly sample subset Cs from clients Compute base accuracy A0 using θ on D_val for each client k in Cs do Load θk and evaluate Ak on D_val Δk ← max(0, Ak–A0) # Truncate negatives φk ← φk + Δk end for end for Normalize: φk ← φk/(sum(φk) + ε), where ε ≪ 1 return {φk} |

To optimize resource allocation and training efficiency, each client can adjust its computational resource usage based on its evaluated contribution. UAVs with higher Shapley values may be prioritized in subsequent training rounds. This approach optimizes resource allocation and contributes to improved global model performance. To precisely reflect each client’s impact on the global model, the Shapley value is introduced as a weighting factor in the model update phase. By evaluating the marginal contribution of each client across different coalition combinations, the Shapley-based weighting scheme ensures a fair and effective aggregation strategy.

Assuming a total of N clients, the Shapley value for each client is computed by evaluating its marginal contribution across all possible subsets of participants. The marginal contribution of a client is defined as the change in the utility of the global model when the client is added to a subset. The Shapley value for client i is given by

where S is the set of client terminals participating in the training, is the contribution of subset S, and is the contribution of subset S when it is added to client i.

In the global aggregation phase, the contribution proportion of each client is determined using a marginal contribution-based allocation, computed according to the Shapley value:

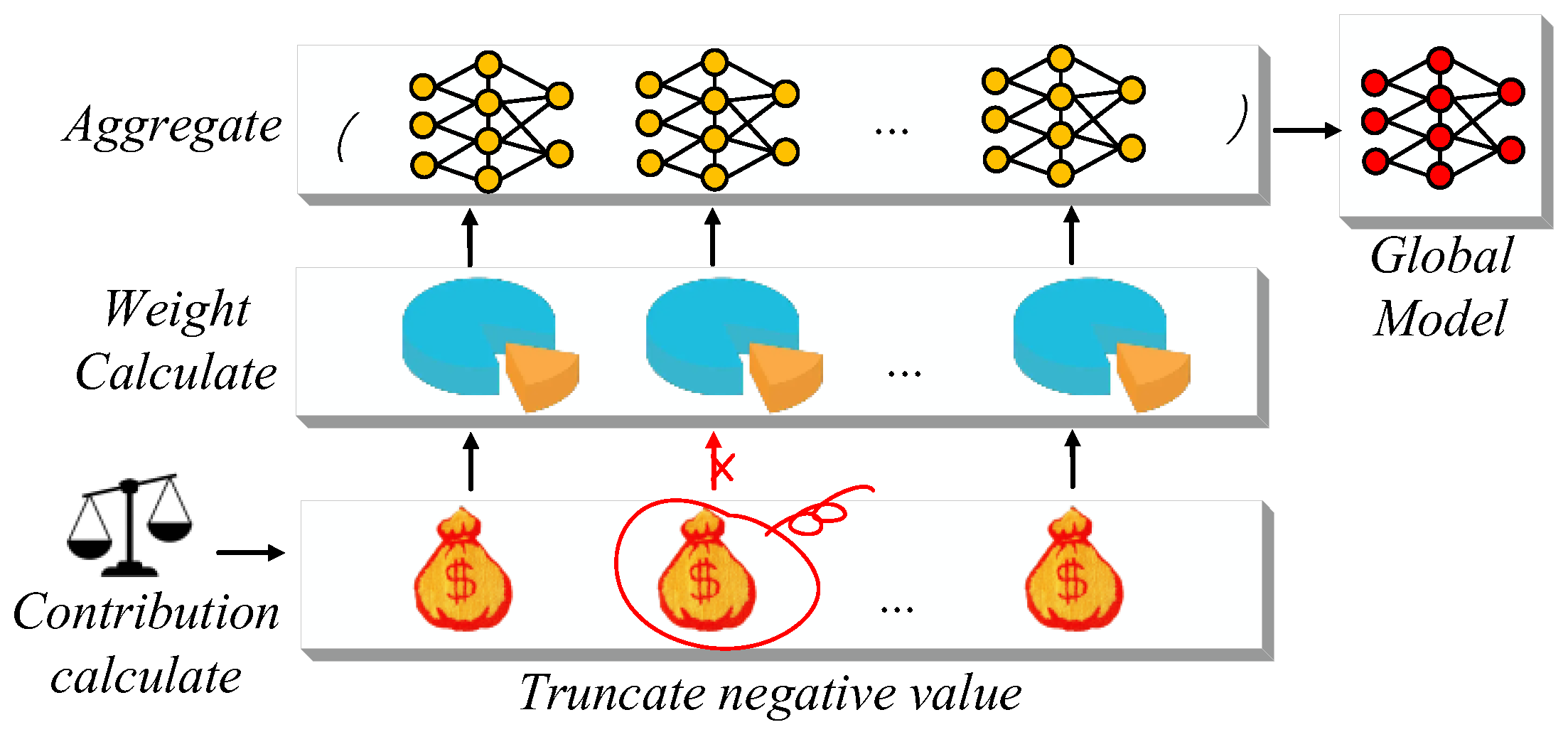

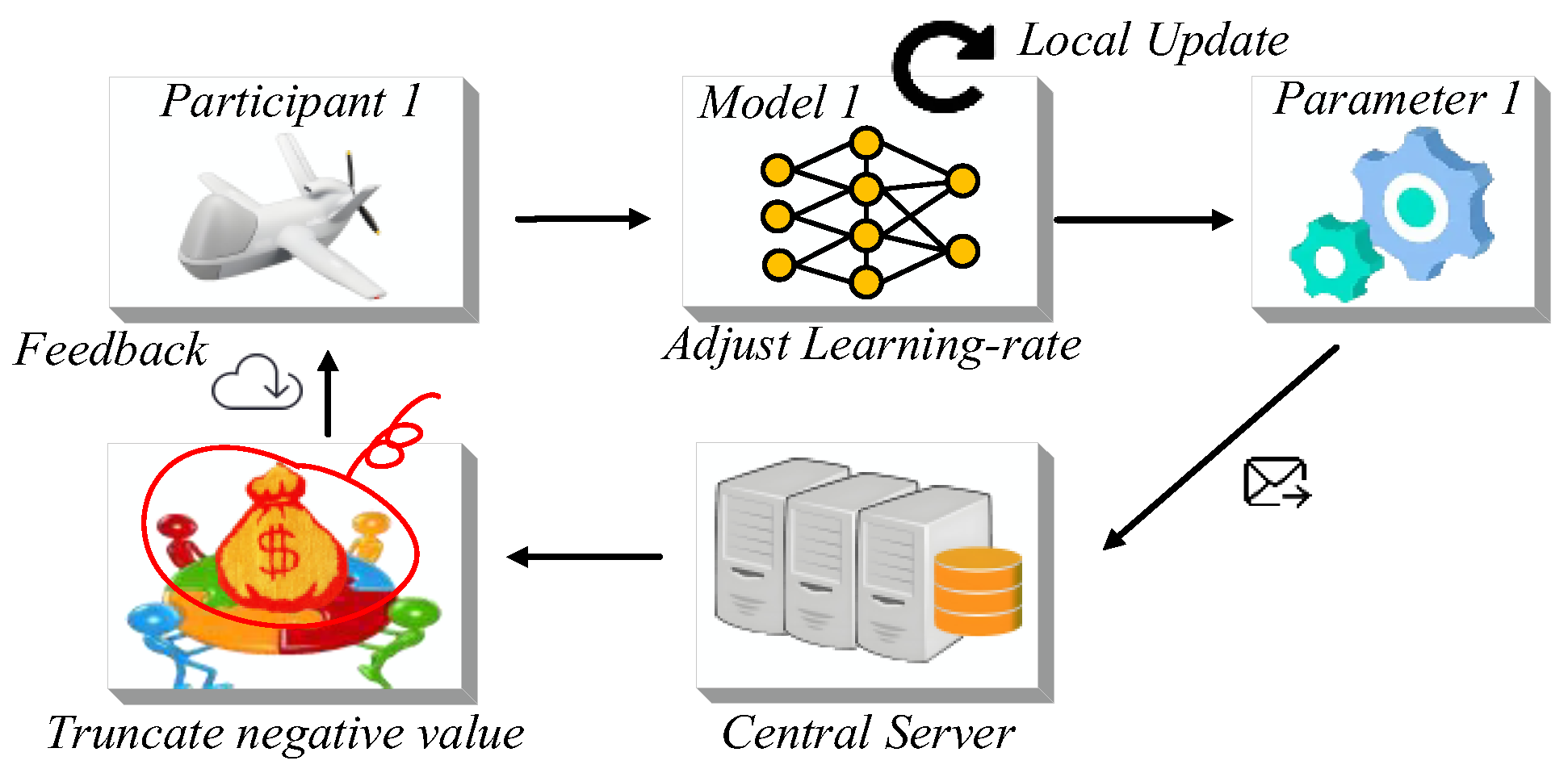

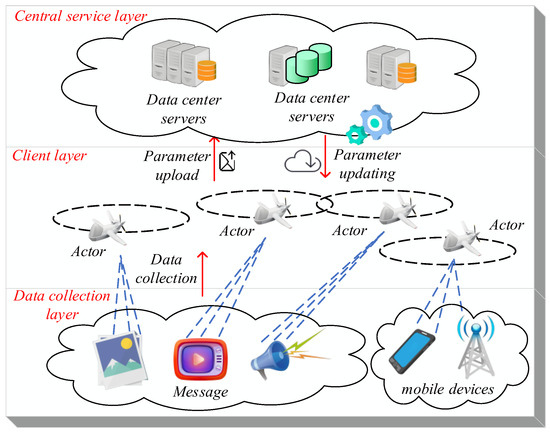

As illustrated in Figure 2, the contribution of each client is explicitly incorporated in the weighted aggregation process. This mechanism ensures that clients with higher marginal contributions exert greater influence on the global model update.

Figure 2.

The central server performs the marginal contribution weighted aggregation process. Yellow solid dots indicate local model nodes, and red solid dots represent the global model after aggregation.

The exact computation of Shapley values requires enumerating all possible client subsets, resulting in a factorial-time complexity of , which is computationally prohibitive for large-scale federated systems. To mitigate this issue and enable scalable, real-time contribution evaluation, a Monte Carlo sampling-based approximation algorithm is adopted. Instead of exhaustive subset enumeration, this approach randomly samples a limited number of coalitions to estimate each client’s marginal contribution. This strategy significantly reduces computational complexity while preserving high approximation accuracy, making it well-suited for dynamic feedback scenarios in resource-constrained multi-agent environments.

For each sampled subset , the marginal contribution of client is estimated by computing the difference in model utility: . The approximate Shapley value of client is then obtained by averaging its marginal contributions across multiple randomly sampled subsets:

It is worth noting that the local cross-entropy loss in Equation (1) is a standard evaluation metric used in federated learning methods (e.g., FedAvg [28], FedBN [34], and MOON [30]) to estimate each client’s marginal contribution within Monte Carlo sampling. Rather than being a purely heuristic simplification, this approach provides a theoretically grounded and widely adopted approximation of the Shapley value in practical federated settings. The overall training process is presented in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2: TVCL_Main. |

| Input: number of clients K, total communication rounds T, client participation fraction C, initial global model θ0, local client datasets D1, D2, …, D_K, validation set for Shapley estimation D_val Output: Final global model θᴛ Initialize global model θ0 for each round t = 1 to T do Randomly select client subset St with m = max(C × K, 1) for each client k in St (in parallel) do θkt, Lkt ← LocalTrain(θt−1, Dk) end for if t < switch_round then Assign uniform weights: φk ← 1/|St| for all k in St Else φk ← Shapley Estimation({θkt}, θt−1, D_val) end if For all non-participating clients, set φk ← 0 Aggregate: θt ← sum over k=1 to K of φk × θkt Evaluate: acc, loss, f1, var ← Evaluation(θt, D_test) Log results for round t end for return θt |

3.2. Hierarchical Weighting Strategy Guided by Cost Function

In distributed training, clients share the same model architecture, but stochastic initialization and uneven participation can hinder generalization if training rounds are in-sufficient. On the other hand, excessive rounds increase computation, energy use, and communication overhead, especially in UAV swarms. To balance performance and cost, we establish a cost model that considers computation, communication, and energy. By analyzing cost dynamics across different round settings, we identify a minimum-cost interval to guide local training and global aggregation frequency.

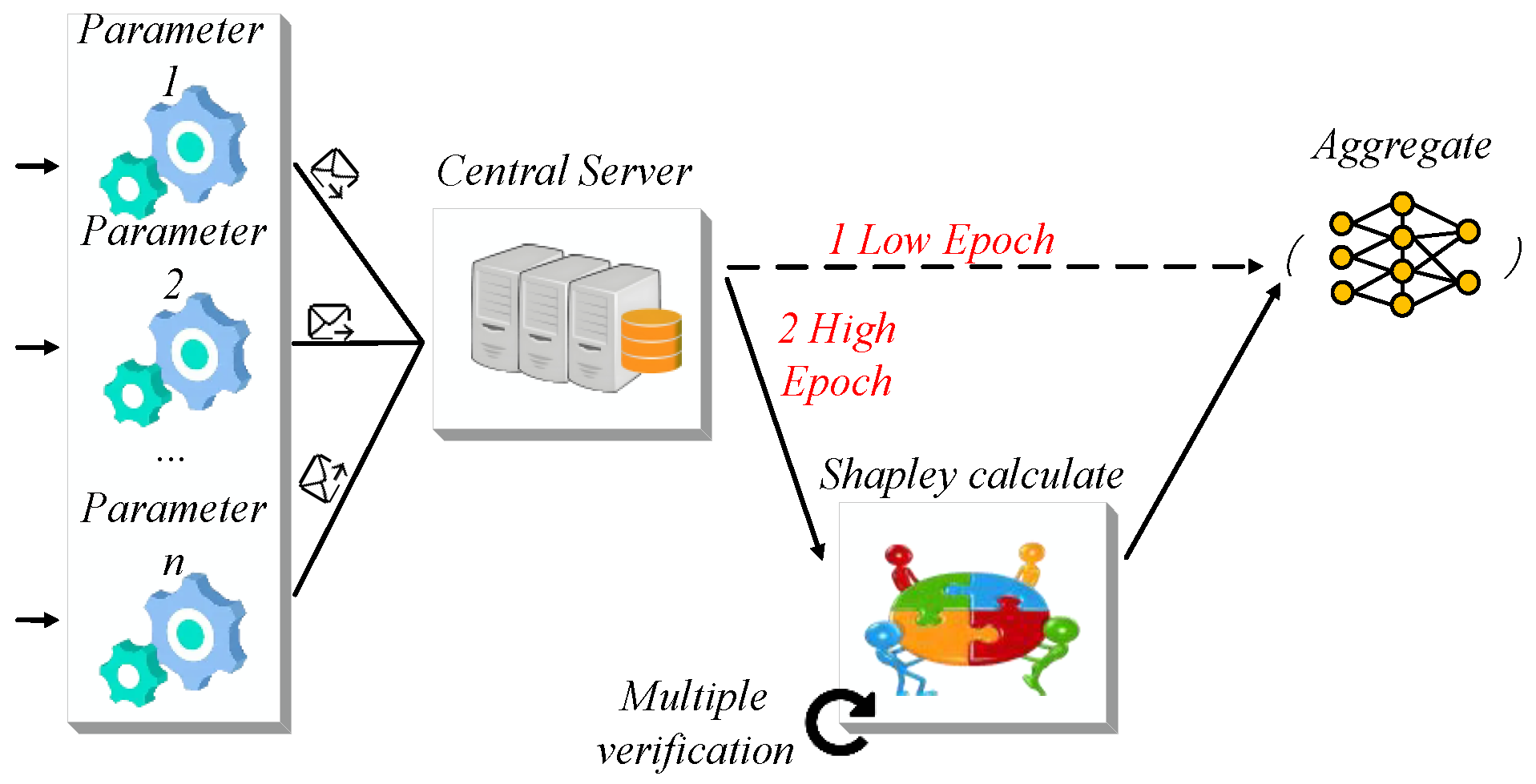

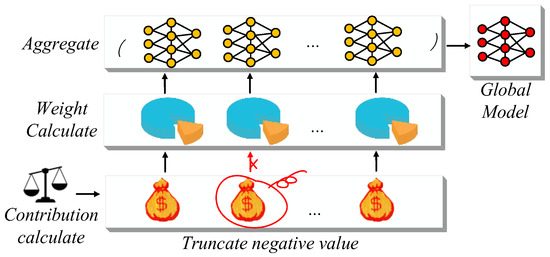

Based on the optimal training interval, early-stage aggregation adopts equal weighting, while later stages use Shapley-based dynamic weights to reflect client contributions. The switch point is determined by each device’s communication and computational capacity. In bandwidth-limited but delay-tolerant scenarios, higher model maturity is preferred to reduce communication frequency. Conversely, under strict latency demands, faster local updates with lower model maturity help ease communication pressure. These trade-offs are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The cost function influences the model hierarchical polymerization process. The arrows indicate the transmission paths of local model parameters. The orange cylinder represents the cloud server responsible for central aggregation, while the yellow node network denotes the aggregated global model prepared for the next training iteration.

Increasing local training rounds can improve model accuracy but also increases computational load and communication latency, potentially affecting real-time responsiveness. To balance accuracy and system cost, we propose a simplified cost–benefit model that quantifies trade-offs among computation, communication, and accuracy gain. The model is fitted using experimental data to capture realistic cost trends, enabling quantitative analysis of how training configurations impact resource consumption and performance.

The total cost function is defined as follows: Here, k1 and k2 are proportional coefficients used to weight different cost components. To balance the influence of the three contributing factors, both coefficients are set to be of the same order of magnitude:

Specifically, let denote the number of local training epochs per client, represent the batch size used in each training iteration, and indicate the computational complexity of the model. These factors jointly determine the computational overhead incurred during local updates.

The communication cost is quantified based on three key factors: the upload frequency of local models, the size of transmitted model parameters, and the available communication bandwidth. Specifically, let denote the number of UAVs participating in each training round, represent the size of the local model to be uploaded, and denote the available communication bandwidth. These parameters are used to compute the effective communication load and assess the communication overhead introduced by federated aggregation.

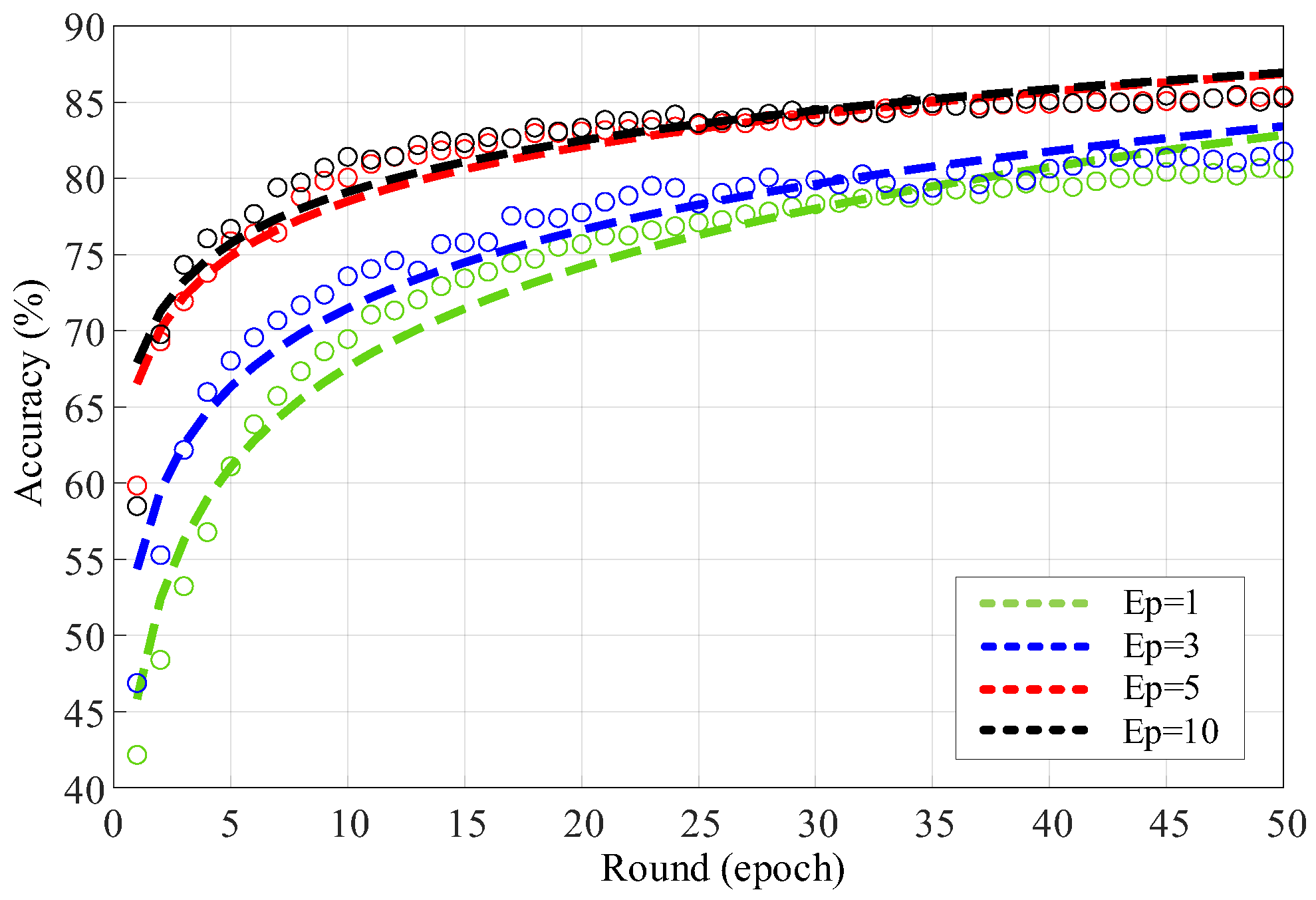

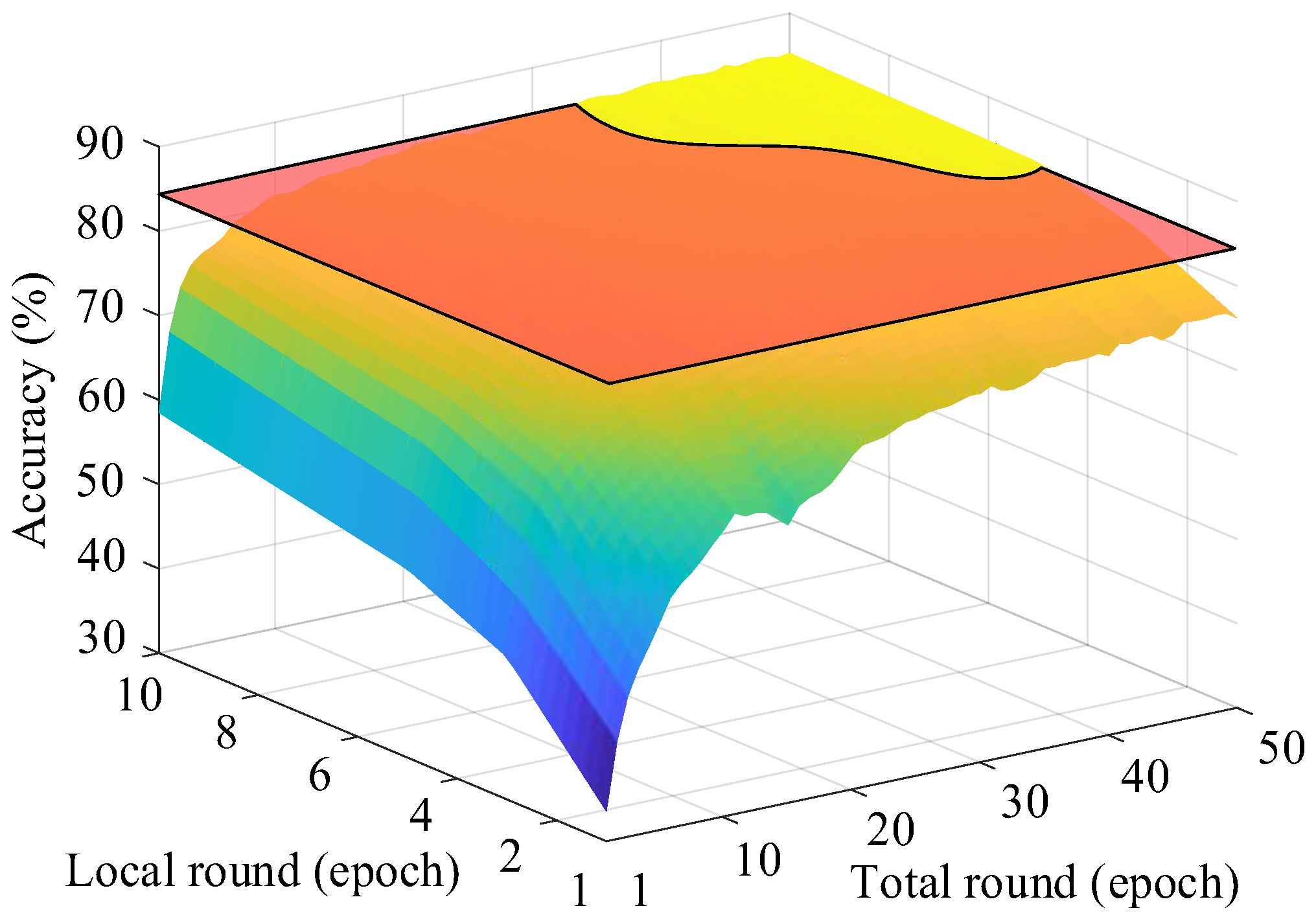

Increasing the number of training rounds generally improves model accuracy; however, the rate of improvement exhibits diminishing returns as the number of rounds in-creases. To quantify this phenomenon, model accuracy was evaluated under varying local training rounds: 1, 3, 5, and 10. A logarithmic regression fitting was applied to capture the relationship between training rounds and accuracy, and to estimate the constant representing the marginal gain in model performance. This regression allows for a more precise understanding of how training effort translates into performance improvement, facilitating informed decisions in the trade-off between computational cost and model accuracy.

The functional dependency of model benefit on the number of local training rounds is defined as:

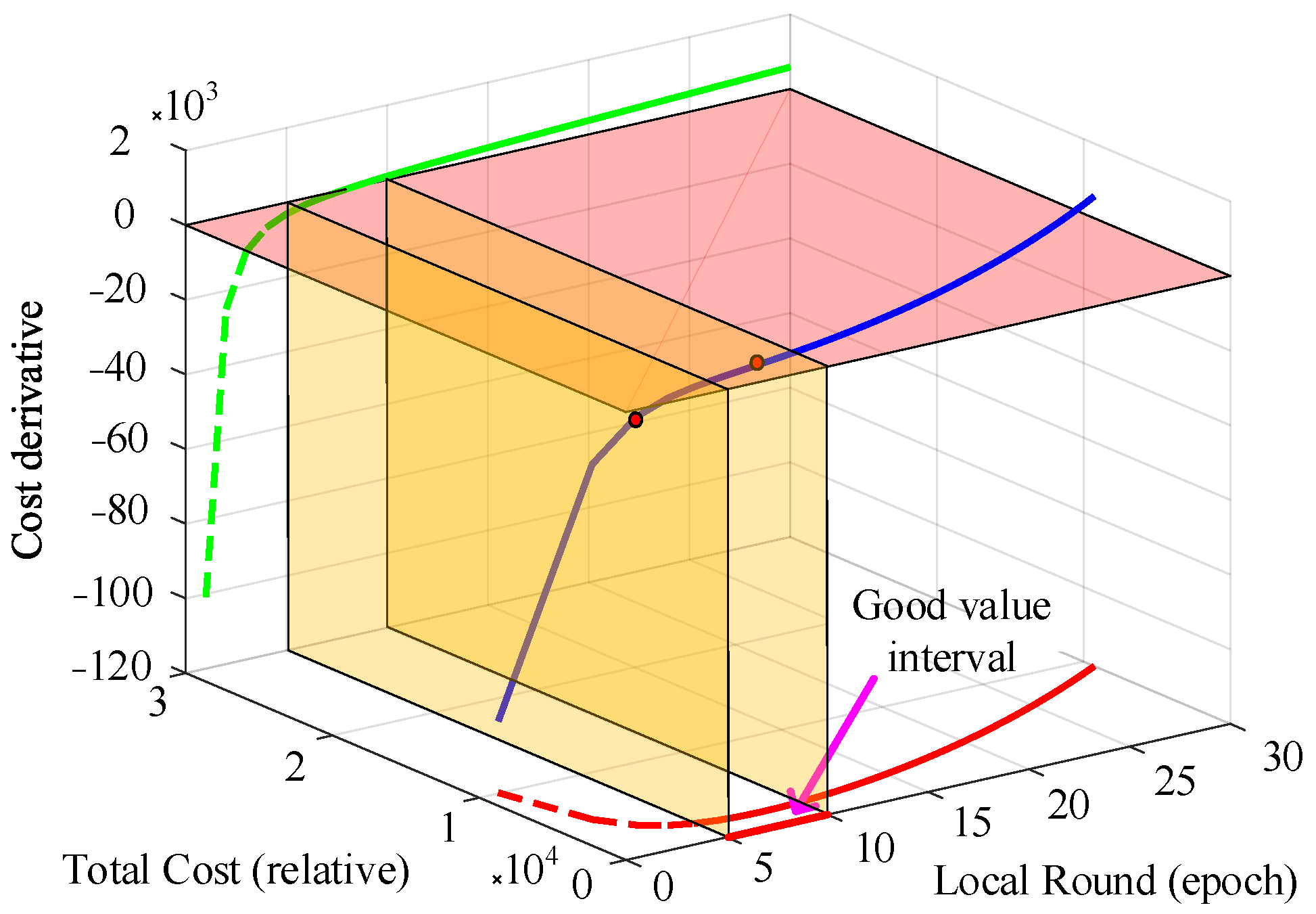

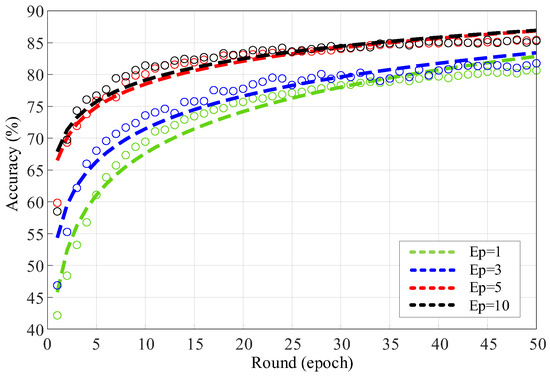

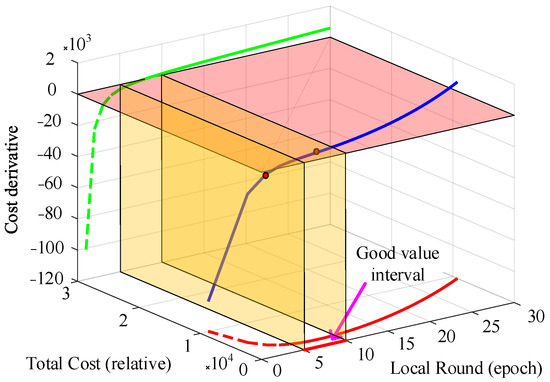

The fitted parameters ( = 10, = 0.8, = 30) were jointly obtained from the regression results illustrated in Figure 4 and Figure 5, where Figure 4 presents the logarithmic fitting between local training rounds and model accuracy, and Figure 5 visualizes the corresponding total cost curve and its derivative to determine the low-cost equilibrium interval. The regression achieved an R2 = 0.972, confirming that the selected parameters accurately capture the diminishing-return trend of local training and provide a realistic basis for cost–benefit analysis.

Figure 4.

Fitting Performance of Local Training Round Number on Model Accuracy. The green, blue, red, and black lines correspond to local training epochs of 1, 3, 5, and 10, respectively. The hollow circular markers represent the measured data points, and the adjacent dashed curves indicate the fitted accuracy trajectories.

Figure 5.

The total cost function and its first-order derivative change with the degree of local training. The blue curve shows the 3D trajectory of the cost function and its derivative across local epochs. The green and red curves are its projections onto the xy- and xz-planes, while the semi-transparent yellow plane marks the interval where the derivative approaches zero. The red dot indicates their intersection point.

Based on the cost model, Figure 5 shows that the total cost forms a convex curve with a clear minimum. In the early training rounds (within 3 rounds), cost drops rapidly; between 5 and 10 rounds, it remains low and stable. Beyond 10 rounds, cost rises sharply due to increased computational and communication overhead. Considering UAVs’ real time constraints, we select the left boundary of the low cost interval as the initial training level—a configuration that balances efficiency and accuracy, as validated by simulation results.

The local update phase is summarized in Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3: Local_Train. |

| Input: global model θ, local dataset Dk, local training epochs E, learning rate η, batch size B Output: Updated model θk, Local training loss Lk Determine training phase and assign weights Initialize local model θk ← θ Set optimizer (SGD/Adam) and learning rate scheduler Initialize best_loss ← ∞, trigger_times ← 0 for epoch e = 1 to E do for each minibatch (x, y) in Dk do Predict: ŷ ← θk(x) Compute loss: L ← CrossEntropy(ŷ, y) Backward and update: θk ← θk–η × ∇L end for Scheduler.step() # optional LR decay if current_loss < best_loss: best_loss ← current_loss; trigger_times ← 0 else: trigger_times += 1 if trigger_times ≥ patience: Stop early end for return θk, average_loss |

After E rounds of central aggregation, the global model begins to capture and generalize key data features across clients. To accelerate the subsequent learning process, dynamic weighting based on Shapley values is introduced. Specifically, each client is assigned a weight according to its marginal contribution to the global model, as measured by the Shapley value. These values are then used to adjust the aggregation weights of the corresponding local submodels. The formulation for computing the aggregation weight based on Shapley values is as follows:

This strategy enables clients with higher contributions during later training stages to receive greater aggregation weights, thereby accelerating the convergence of the global model. It also ensures that the most informative and reliable nodes are prioritized in the model update process during the later phases of training. Meanwhile, local models can still participate in the collaborative learning process at a lower cost, without compromising the quality of the extracted feature information.

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

3.3. Adaptive Contribution-Based Optimization Mechanism

Due to the resource constraints of multi-UAV systems and the presence of heterogeneous data, the quality of local model training is often lower than expected, which can negatively impact the global model when such nodes are included in aggregation. To address this issue and ensure reliable node contribution, monitoring mechanisms are integrated into the local training process to detect potential declines in convergence efficiency. Specifically, if the local loss function continues to decrease for n consecutive rounds (where n = ⌈E/2⌉, and E is the total number of local training epochs), it is inferred that the model has sufficiently learned the local data characteristics. At this point, a learning rate decay mechanism is triggered to slow down local training updates. This not only prevents overfitting but also allows other clients with more informative data to contribute more effectively in the global aggregation.

The learning rate adjustment formula is given as follows:

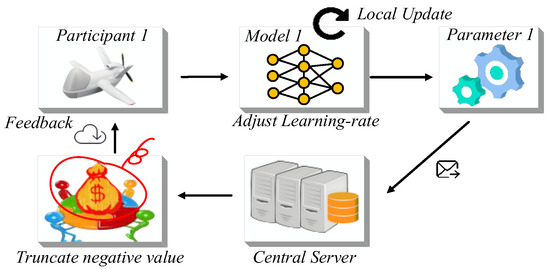

Secondly, during contribution evaluation at the central server, a negative contribution truncation strategy is employed. Only clients with positive marginal contributions are selected to participate in model aggregation, while those with negative contributions are excluded. This selective aggregation mechanism ensures that only the most effective nodes influence the global model, thereby accelerating convergence and enhancing overall training efficiency.

This process is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Global control of high-quality nodes to participate in the training process. The yellow network illustrates the adaptive local model aggregation process, whereas the orange cylinder indicates the central server responsible for global aggregation.

To quantify the effectiveness of the global model and assess the marginal contributions of participating nodes, a standardized evaluation mechanism is implemented. This algorithm systematically measures key performance metrics on a held-out test dataset, enabling the server to objectively rank clients and execute the negative contribution truncation strategy outlined in Section 3.3. The evaluation process iterates over batched test samples, computing prediction accuracy, average cross-entropy loss, F1-score (to balance precision and recall), and loss variance (to quantify prediction stability). These metrics collectively reflect the model’s generalization capability and robustness, providing critical insights for filtering low-contribution nodes during aggregation. The pseudocode below formalizes this evaluation workflow, aligning with the quality control framework illustrated in Figure 6. The global evaluation procedure is shown in Algorithm 4.

| Algorithm 4: Evaluation. |

| Input: global model θ, test dataset D_test, batch size B Output: Accuracy, average loss, F1-score, loss variance Initialize total_loss ← [], correct ← 0 for each batch (x, y) in D_test do Predict: ŷ ← θ(x) Compute per-sample loss: ℓ ← CrossEntropy(ŷ, y) Append ℓ to total_loss Count correct predictions Store ŷ and y for F1 calculation end for Compute accuracy ← correct/total samples Compute avg_loss ← mean(total_loss) Compute var_loss ← variance(total_loss) Compute F1 ← weighted F1-score(ŷ, y) return accuracy, avg_loss, F1, var_loss |

3.4. Communication Cost Modelingt

In the proposed framework, we incorporate a communication-aware analysis to estimate the cost of model synchronization in each global round. Let S denote the size of the global model in bytes, Nr the number of participating clients per round, and B the available bandwidth per client in bytes per second. The communication time per round is computed as:

Given that our model (EfficientNet-B0) has approximately 5.3 million parameters, the total upload cost per client per round is roughly 21.2 MB. Under 0.75 participation ratio and 50 global rounds, the estimated total communication cost reaches 6.36 GB per client. To evaluate the effect of communication constraints, we simulate varying bandwidth conditions ranging from 0.1 Mbps to 10 Mbps and analyze their impact on convergence performance.

To validate the practical implications of the proposed cost model, we conduct a supplementary evaluation in Section 4.4 under simulated bandwidth-constrained environments.

3.5. Complexity Analysis and Runtime Comparison

The computational complexity of the proposed TVCL framework mainly arises from three components: (1) local model training, (2) global aggregation, and (3) Monte Carlo-based Shapley estimation. For comparison, the asymptotic time complexity of FedAvg and FedProx are both O (K⋅E⋅n), where K denotes the number of clients, E the local epochs, and n the average number of samples per client.

In TVCL, the additional Shapley approximation step incurs O(M⋅K) operations, where M is the number of sampled coalitions (typically M ≪ K!). Therefore, the overall complexity remains O(K⋅E⋅n + M⋅K), which grows linearly with the number of clients and sampling iterations. The space complexity is identical to FedAvg, as the algorithm does not require storing all coalition models but only temporary validation results per sample. In Section 4.2, when trained on CIFAR-10 with 8 clients and 50 rounds, TVCL achieved convergence within 1.23× the runtime of FedAvg and 1.09× that of FedProx, on the MNIST dataset, TVCL exhibited even faster convergence than both baselines. reflecting a moderate computational overhead in exchange for improved stability and accuracy.

4. Results

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed framework, we conducted extensive simulations using multiple evaluation metrics and baseline algorithms. The simulation environment reflects typical federated learning conditions, assuming all participants remain active, possess sufficient data, and communicate reliably. These controlled assumptions provide a stable basis for evaluating core performance.

The framework was implemented in PyCharm (version 2023.2.2) and tested across five independent runs, confirming consistent client contribution rankings and robust accuracy behavior. UAVs were randomly deployed, with clients uploading local models to a central server each round, followed by global model redistribution. Four baselines—FedAvg, pFedMe, FedBN, and MOON—were tested under identical conditions. Experimental settings are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Experiment parameters.

4.1. Experimental Evaluation of Cost Function Effects

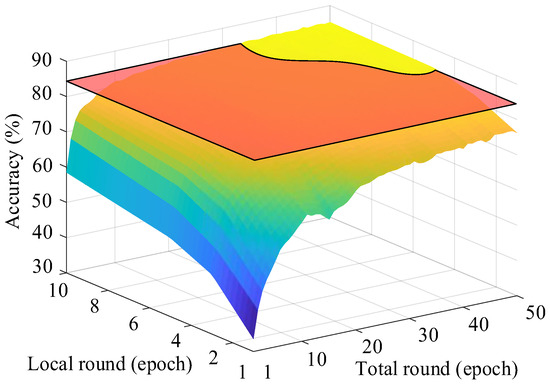

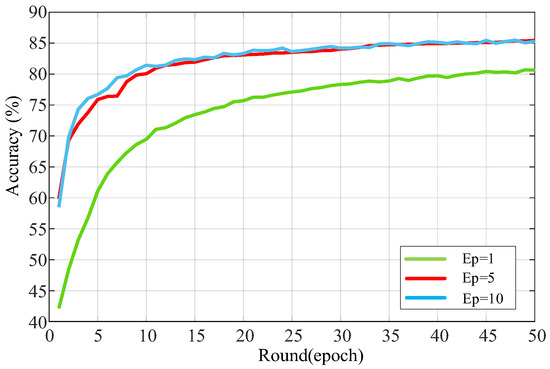

Figure 7 illustrates the convergence behavior of the global model under different local training round settings, ranging from 1 to 10 and including 50 rounds as an extended comparison. The results show that selecting the number of local training rounds within the recommended interval of 5 to 10 yields both higher model accuracy and faster convergence. This demonstrates that the choice of local training rounds has a significant impact on both the convergence rate and the final performance of the global model.

Figure 7.

The training accuracy of global model varies with the number of training rounds and the training degree of single model. The orange semi-transparent plane highlights the region where the accuracy exceeds 85%.

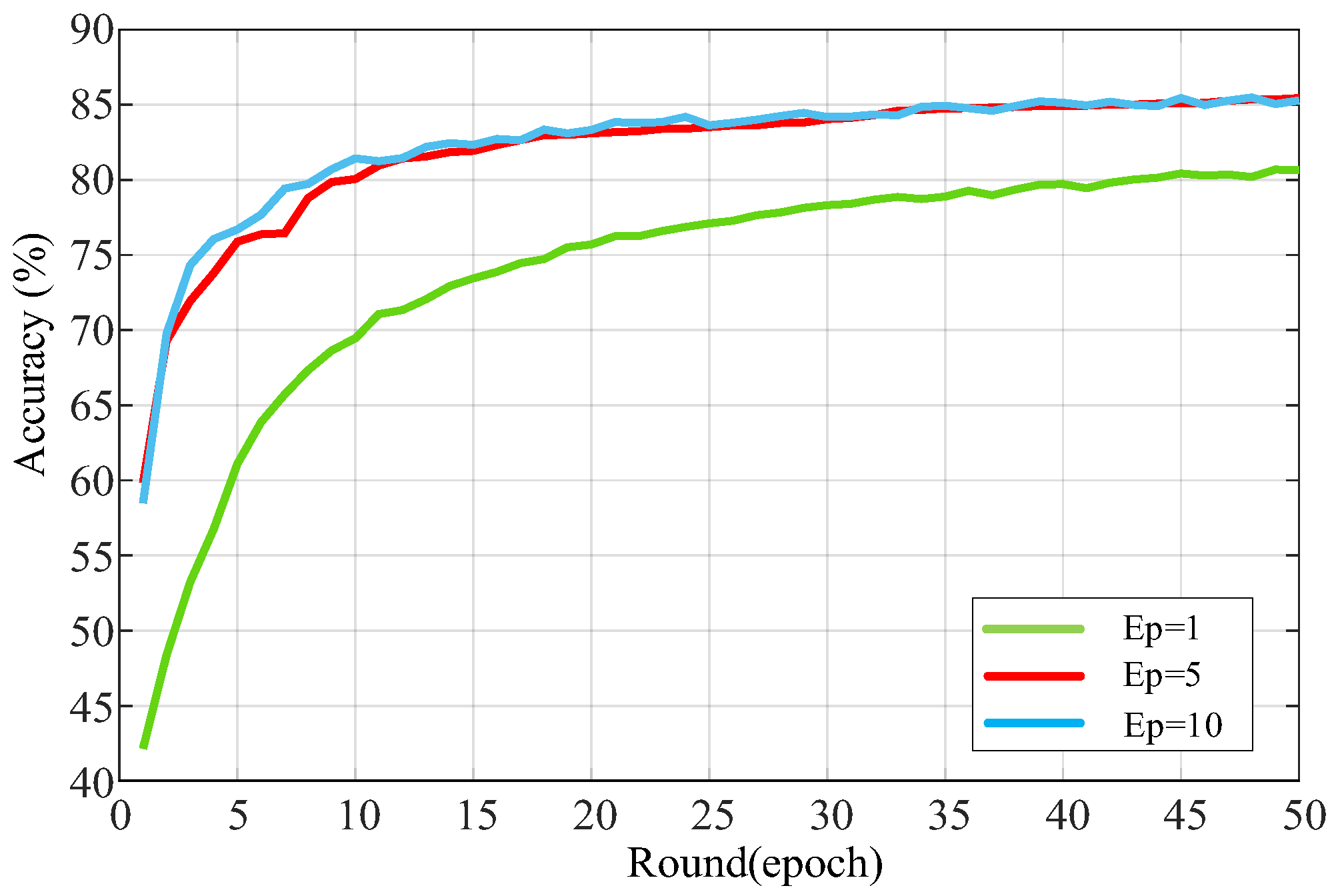

Figure 8 shows model accuracy under three local training settings: E = 1, 5, and 10. With E = 1, the model con-verges slowly and plateaus around 70% accuracy, due to insufficient local updates despite frequent global synchronization. In contrast, E = 5 and E = 10 achieve faster convergence and higher early-stage accuracy. Notably, although E = 10 converges quicker initially, E = 5 attains a slightly higher final accuracy (~85.5%), suggesting that a moderate number of local steps offers a better trade-off be-tween convergence and resource efficiency.

Figure 8.

The training accuracy of the global model with limited low-cost interval training equilibrium points 1, 5, and 10 was selected to change with the number of training rounds.

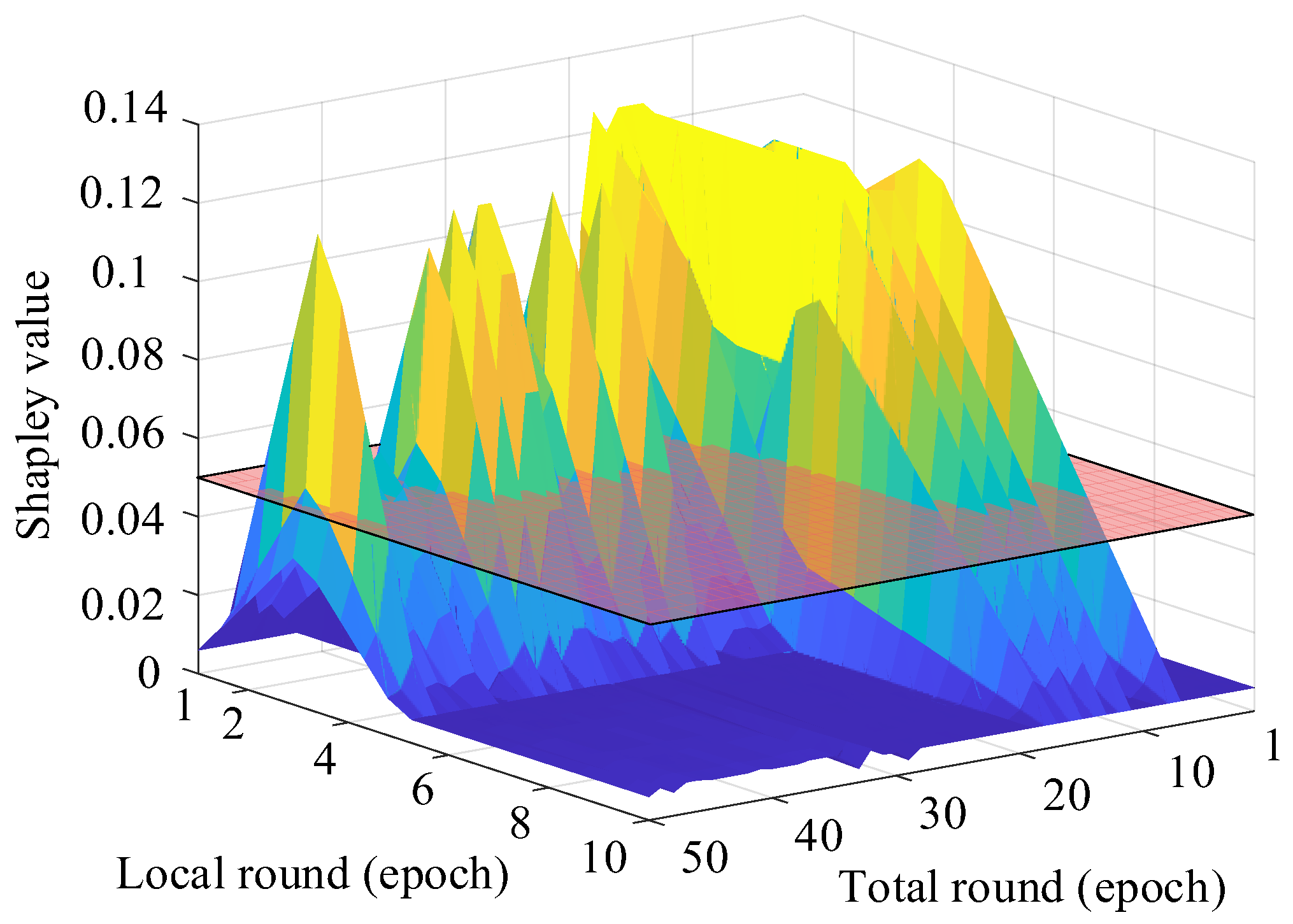

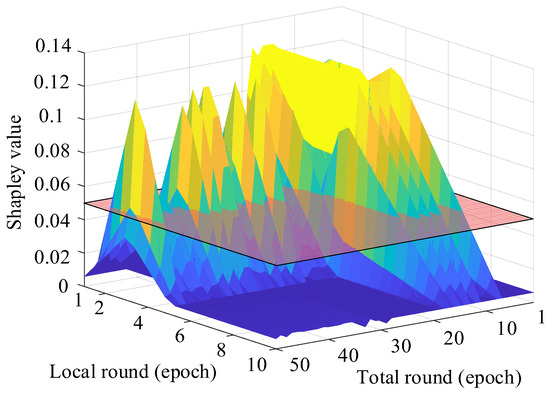

The effect of the cost function is also evident in the convergence of Shapley values. To assess the use of heterogeneous data, we tracked the maximum change in Shapley values per round under different equilibrium settings. As shown in Figure 9, when the setting is 5 or higher, Shapley value fluctuations steadily decline, indicating that high-contribution clients are quickly integrated. This trend con-firms the effectiveness of the proposed cost-aware strategy in capturing valuable data early in training.

Figure 9.

The graph and top view showing the variation in the global maximum Shapley value with respect to the degree of local training and the number of global rounds. The semi-transparent red plane separates regions with Shapley values above 0.05 (empirically determined), illustrating the relationship between heterogeneous client data and training-parameter settings.

Among all settings, Ep = 5 offers the best trade-off between convergence speed, accuracy, and computational cost. It proves to be the most effective configuration for the proposed TVCL method under the parameters in Table 2. These results validate that TVCL’s equilibrium estimation mechanism successfully identifies a cost-efficient training setup, leading to superior performance.

4.2. Shapley-Based Aggregation Under Varying Equilibrium Strategies

To evaluate the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed TVCL framework, we conducted comparative experiments against baseline algorithms in a simulated UAV swarm environment. Three key metrics—accuracy, F1-score, and loss variance—were assessed on CIFAR-10 and MNIST. Accuracy measures predictive performance, F1-score reflects class balance, and loss variance indicates model stability. These metrics are crucial in multi-UAV systems with heterogeneous data, where instability can lead to mission failure. This evaluation aims to verify whether TVCL achieves a balanced trade-off between precision, fairness, and training stability under non-IID, re-source-constrained conditions.

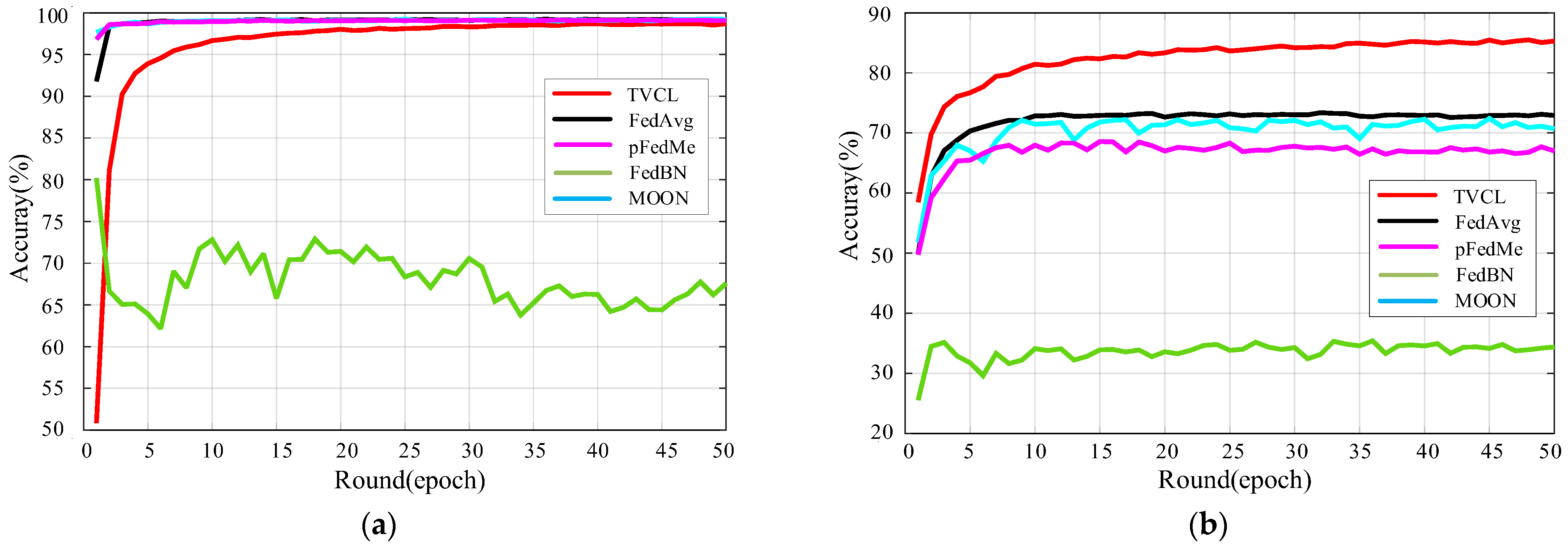

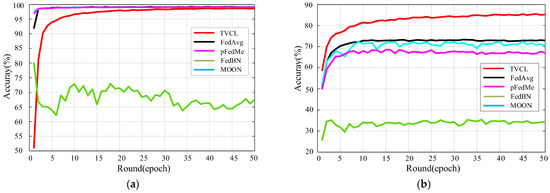

Figure 10a compares the accuracy performance of five federated learning algorithms: TVCL, FedAvg, pFedMe, FedBN, and MOON. TVCL demonstrates significantly faster convergence, reaching near-optimal accuracy within 10 communication rounds and consistently maintaining test accuracy above 98% throughout training.

Figure 10.

The accuracy curves of our TVCL method and other methods on the MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets. (a) Results on the MNIST dataset; (b) Results on the CIFAR-10 dataset.

Figure 10b illustrates convergence on the more challenging non-IID CIFAR-10 dataset. TVCL surpasses 85% accuracy by round 50, outperforming FedAvg (~78%), pFedMe (~73%), and others. The stagnation of FedBN and MOON reflects poor adaptation to data heterogeneity. TVCL’s advantage stems from its Shapley-based dynamic weighting and cost-aware optimization, which jointly improve convergence and final performance in heterogeneous settings.

TVCL accelerates convergence and enhances final model performance, demonstrating strong robustness to non-IID data and effective client collaboration guided by real-time contribution evaluation. As shown in Table 3, the proposed TVCL method achieves the highest accuracy on the CIFAR-10 dataset (85.23%), outperforming the second-best baseline, FedAvg (72.92%), by over 12%. TVCL also demonstrates strong robustness, with a standard deviation of ±0.18% and a fluctuation range of just 0.58% across repeated trials. In contrast, FedBN and MOON exhibit both lower accuracy and higher variability—for example, FedBN only reaches 34.40% accuracy with a 1.61% range. These results high-light TVCL’s superior performance and stability, making it well-suited for non-IID UAV federated learning tasks. The quantitative results of different federated learning methods on the CIFAR-10 and MNIST datasets are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively.

Table 3.

Accuracy, stability, and variance comparison of federated learning methods on the CIFAR-10 dataset.

Table 4.

Performance and stability comparison of federated learning methods on the MNIST dataset.

While TVCL does not achieve the highest accuracy on MNIST (98.70%), it remains competitive with top-performing baselines like FedAvg and MOON (both at 99.21%). More importantly, TVCL demonstrates greater robustness than FedBN, which shows significant instability with a 3.55% accuracy range and ±1.14% standard deviation under non-IID conditions. Despite its slightly lower accuracy, TVCL offers a balanced trade-off between performance and stability—crucial for UAV-based federated learning where resource limits and data heterogeneity are common. With further tuning, TVCL shows strong potential for real-world generalization.

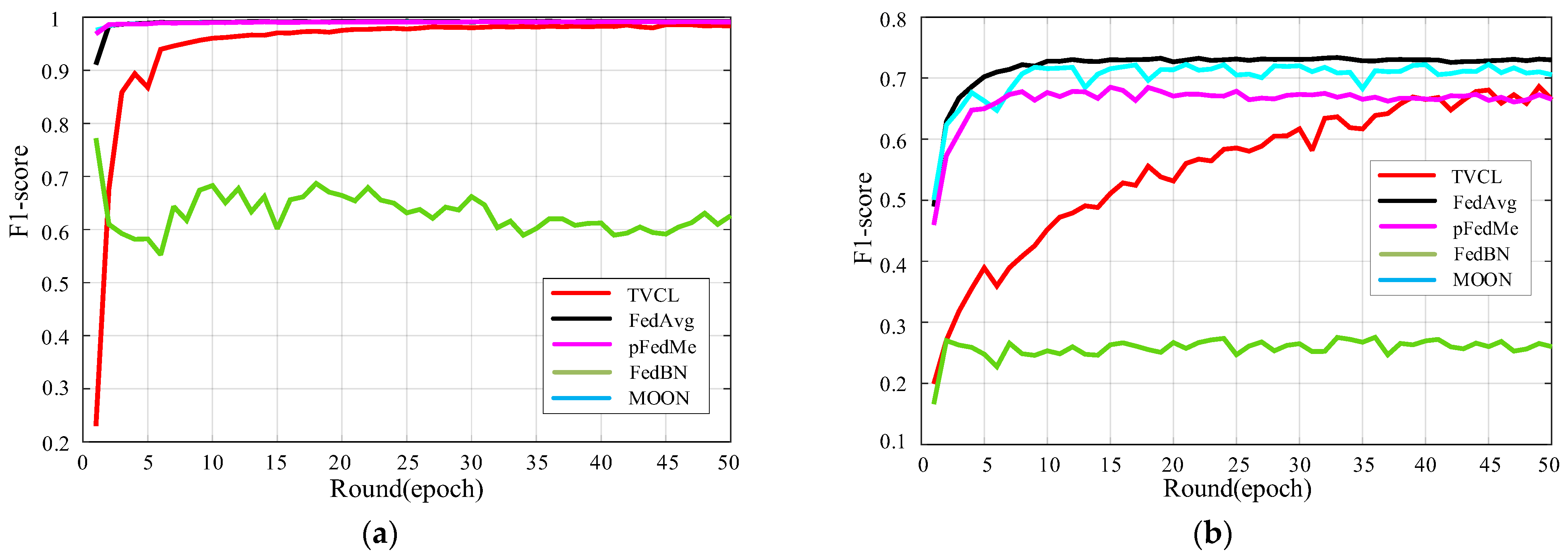

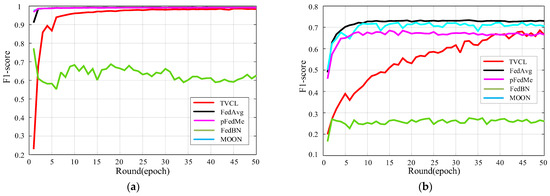

Figure 11a shows the F1-score progression of five federated learning methods on the non-IID CIFAR-10 dataset. Although TVCL does not lead initially, it exhibits a steady upward trend, eventually surpassing FedBN and MOON and approaching the performance of FedAvg and pFedMe. Its low variance and stable improvement highlight strong adaptability to data heterogeneity, suggesting good potential for real-world UAV applications with imbalanced data.

Figure 11.

F1-score comparison on MNIST and CIFAR-10 dataset across communication rounds. (a) Results on the MNIST dataset; (b) Results on the CIFAR-10 dataset.

On the structured MNIST dataset, TVCL achieves a near-optimal F1-score (~0.98) within a few rounds, matching the performance of FedAvg and pFedMe. Although FedAvg performs slightly better in early stages, TVCL shows more stable convergence with less fluctuation and no performance degradation over 50 rounds. These results confirm TVCL’s ability to maintain high accuracy and stability, making it well-suited for mission-critical multi-UAV federated learning scenarios.

Table 5 summarizes the accuracy, F1-score, and loss variance of five federated learning methods on CIFAR-10 and MNIST. On CIFAR-10, TVCL achieves the highest accuracy (85.23%), confirming its strength in handling highly non-IID data. While its F1-score is slightly below FedAvg and MOON, overall performance remains competitive. The higher loss variance (0.8516) reflects dynamic early adaptation rather than instability. On MNIST, TVCL reaches near-optimal accuracy and F1-score, slightly trailing FedAvg and MOON but showing greater consistency than FedBN. These results confirm that TVCL provides an effective balance between accuracy, robustness, and generalization, especially in heterogeneous, resource-constrained settings.

Table 5.

The experimental results of CIFAR-10 and MNIST datasets.

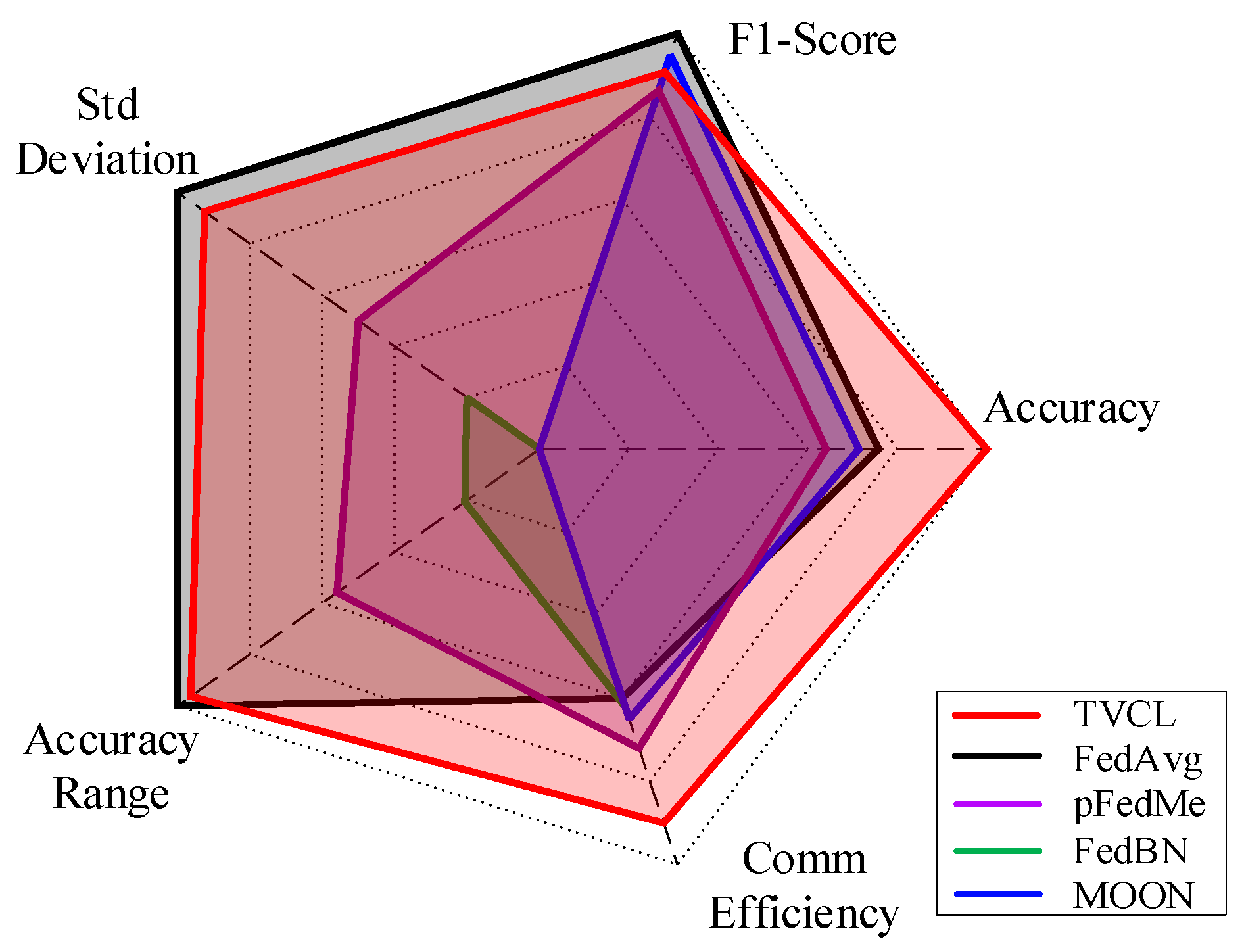

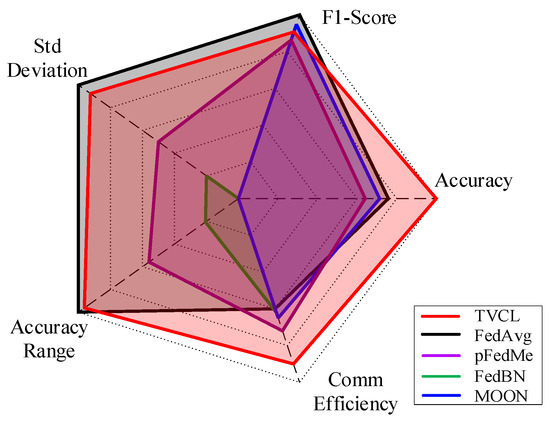

To offer a comprehensive comparison of federated learning algorithms in non-IID UAV scenarios, Figure 12 presents a radar chart covering five key metrics: Accuracy, F1-Score, Standard Deviation, Accuracy Range, and Communication Efficiency. TVCL outperforms baseline methods across most dimensions, particularly in communication efficiency and training stability. It achieves the lowest accuracy fluctuation and variance, highlighting strong robustness under heterogeneous conditions. Although its accuracy on simpler datasets like MNIST is slightly lower than that of FedAvg and MOON, the overall results confirm TVCL’s superior adaptability and generalization in re-source-constrained UAV environments.

Figure 12.

Radar chart comparing TVCL with baseline methods on five metrics. TVCL outperforms others overall, especially in stability and communication efficiency under non-IID UAV settings.

Although MNIST and CIFAR-10 are generic vision benchmarks, they serve as standard and reproducible datasets for evaluating algorithmic behavior under controlled non-IID and communication-constrained conditions. The proposed TVCL framework exhibits strong generalizability in principle and can be adapted to UAV imagery or sensor data with appropriate data preprocessing and cost-function design. In real UAV applications such as aerial monitoring or infrastructure inspection, additional customization of communication models and energy constraints would be required to fully realize its potential under practical operational conditions.

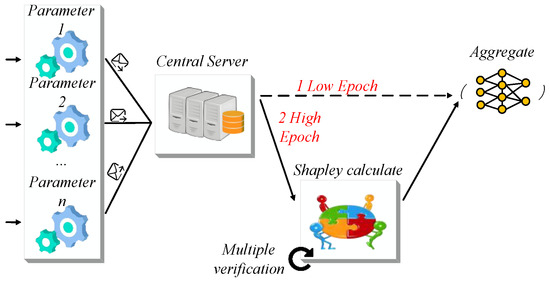

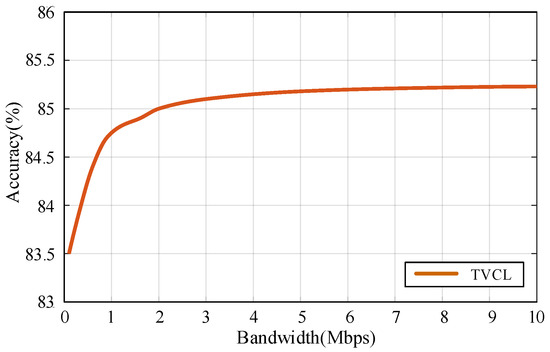

4.3. Evaluation Under Bandwidth Constraints

To evaluate the practical feasibility of TVCL in bandwidth-constrained UAV swarm networks, we simulate communication overhead and final accuracy under uplink bandwidths of 0.1, 1, and 10 Mbps. Table 6 reports the estimated per-round and total communication time, based on a model size of 21.2 MB (EfficientNet-B0), 50 global rounds, and 75% client participation. Even under severe bandwidth limits (0.1 Mbps), TVCL maintains strong performance, achieving 83.5% accuracy with only ~1.7% degradation compared to the high-bandwidth setting.

Table 6.

Impact of communication bandwidth on model convergence time and final accuracy.

While Table 6 quantifies the bandwidth–resource trade-off, Figure 13 reveals a nonlinear relationship between bandwidth and accuracy. The most notable improvement occurs between 0.1 Mbps and 1 Mbps, underscoring the importance of mitigating communication bottlenecks during early training. Beyond 1 Mbps, accuracy gains taper off, reflecting diminishing returns—an expected trend in resource-constrained UAV networks.

Figure 13.

The relationship between communication bandwidth and final model accuracy under linear bandwidth scaling. The model maintains high accuracy even under low-bandwidth constraints, demonstrating robustness and communication efficiency.

This observation validates the communication-aware design of the proposed TVCL framework. By selectively engaging high-contribution UAVs and dynamically adjusting aggregation weights based on Shapley values, the framework maximizes learning effectiveness even under tight bandwidth budgets. These results confirm that our approach not only ensures robust convergence in ideal environments, but also maintains high resilience in degraded communication scenarios—a crucial capability for real-world UAV swarm deployments.

4.4. Discussion on Scalability and Real-World Deployment

Although the proposed TVCL framework demonstrates strong performance under controlled simulation settings, several factors must be considered for real-world UAV deployment:

- (1)

- Packet loss and intermittent connectivity can significantly delay global aggregation or lead to partial model updates. To address this, TVCL can be extended with asynchronous update strategies and communication redundancy mechanisms to ensure robustness against transient disconnections.

- (2)

- Energy-aware scheduling is critical for UAV swarms operating under limited battery capacity. The Shapley-based client evaluation in TVCL naturally supports this requirement by prioritizing high-contribution but energy-efficient nodes for participation, thereby reducing unnecessary computation and transmission overhead.

- (3)

- Scalability in large UAV fleets may introduce additional latency due to increased coordination cost. To mitigate this, hierarchical aggregation (e.g., cluster-based TVCL) can be employed, where local leaders perform intra-cluster aggregation before global synchronization.

These extensions suggest that the proposed TVCL framework can be effectively integrated into resource-constrained UAV systems, maintaining adaptability and efficiency in the presence of real-world communication and energy limitations.

4.5. Ablation and Sensitivity Analysis

To quantify the contribution of each component in the proposed TVCL framework, ablation experiments were conducted on CIFAR-10 with 8 clients and 50 rounds. Table 7 summarizes the effect of successively removing the Shapley weighting, UAV cost function, and truncation mechanism.

Table 7.

Ablation Analysis of the Shapley-based Federated Aggregation Components. The symbol “√” denotes that the corresponding component is included in the ablation setting, while a blank cell indicates that the component is excluded.

Disabling Shapley weighting leads to a sharp 7.8% accuracy drop (from 85.23% to 74.91%), confirming that contribution-aware aggregation is the dominant factor driving convergence under non-IID conditions. Eliminating the cost-function-guided adjustment decreases accuracy by 3.0% (from 85.23% to 82.20%) and lowers the F1-score to 0.6267, indicating that cost awareness improves fairness and resource efficiency. Without the truncation mechanism, the loss variance rises from 0.8516 to 0.9350, showing that filtering low-quality updates stabilizes training. Sensitivity analysis further reveals that the algorithm remains stable when the number of Monte Carlo samples M M ranges between 10 and 30, with performance saturation beyond this range. These results verify that Shapley weighting, cost-aware regulation, and truncation contribute complementary gains in accuracy, fairness, and stability, jointly ensuring the robustness of TVCL.

5. Conclusions

Driven by dynamic, multi-dimensional Shapley value evaluation, this paper proposes a collaborative federated learning framework tailored for multi-UAV systems, significantly enhancing both convergence speed and global model accuracy. A multi-dimensional cost function is formulated by jointly considering communication overhead, computational load, and algorithmic complexity. This function enables the selection of optimal training depth for each client, improving performance under resource-constrained conditions.

In addition, a UAV-specific training adjustment strategy is introduced to ensure positive marginal contributions from all clients, maximizing collaborative efficiency. A time-varying, Shapley-based coordination mechanism further guides inter-UAV collaboration over time.

The proposed method is evaluated on non-IID CIFAR-10 and MNIST datasets. Experimental results show that, while maintaining strong performance on simpler datasets, the proposed framework outperforms baseline algorithms—FedAvg, FedBN, MOON, and pFedMe—by up to 12.31% on more complex datasets. Moreover, it significantly accelerates convergence under highly heterogeneous conditions, confirming its robustness and adaptability in real-world UAV scenarios.

Author Contributions

X.L. and H.Z. wrote the main manuscript text. X.L. conceptualized the study, developed the theoretical framework, and supervised the project; H.Z. and J.C. implemented the algorithms, conducted experiments, and performed data analysis; X.Z. prepared figures and visualizations; G.L. provided methodological guidance and se-cured funding; X.L. and H.Z. drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62402124 and No. 62302062), the Open Project Program of Guangxi Key Laboratory of Digital Infrastructure (Grant No. GXDINBC202402 and No. GXDINBC202407), the Guangxi Science and Technology Base and Talent Project (Grant No. GuikeAD23026160), and the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 2025GXNSFBA069283).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in the MNIST repository (http://yann.lecun.com/exdb/mnist/, accessed on 10 April 2025) and the CIFAR-10 repository (https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar-10-python.tar.gz, accessed on 10 April 2025). Additional data generated during the cur-rent study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, which helped improve the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the existing affiliation information. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Surendar, V.; Raghavendran, P.S.; Poojitha, P.T.; Shivali, S.; Sakthivel, G.; Lokesh, M. Revolutionizing Industries with Aerial Vehicle Using Mobile for Surveillance. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Smart Systems (ICSCSS), Coimbatore, India, 10–12 July 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 154–158. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ye, Y.; Yin, G.; Johnson, B.A. Deep learning in remote sensing applications: A meta-analysis and review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 152, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Wang, Z.; Xia, M.; Wu, L.; Tian, Y.; Chen, Y. Path planning for UAV communication networks: Related technologies, solutions, and opportunities. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdale, J.; Kim, Z.W.; Hedrick, J.K. Autonomous UAV path planning and estimation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2009, 16, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adão, T.; Hruška, J.; Pádua, L.; Bessa, J.; Peres, E.; Morais, R.; Sousa, J.J. Hyperspectral imaging: A review on UAV-based sensors, data processing and applications for agriculture and forestry. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomina, I.; Molina, P. Unmanned aerial systems for photogrammetry and remote sensing: A review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 92, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.; Elias, J.; Martignon, F.; Di Nitto, E. Resource calendaring for mobile edge computing: Centralized and decentralized optimization approaches. Comput. Netw. 2021, 199, 108426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamissi, A.; Dhraief, A.; Sliman, L. A Comprehensive Survey on Conflict Detection and Resolution in Unmanned Aircraft System Traffic Management. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 26, 1395–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlagh, N.H.; Taleb, T.; Arouk, O. Low-altitude unmanned aerial vehicles-based internet of things services: Comprehensive survey and future perspectives. IEEE Internet Things J. 2016, 3, 899–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Li, Q.; Peng, Z.; Liu, X.; Cui, D. Energy harvesting computation offloading game towards minimizing delay for mobile edge computing. Comput. Netw. 2022, 204, 108678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, H.; Hwang, S.; Debbah, M.; Lee, I. Cooperative multi-agent deep reinforcement learning methods for uav-aided mobile edge computing networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 38040–38053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.N.; Singh, R.; Turjya, S.M.; Ahuja, P.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Swain, S. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles by Implementing Mobile Edge Computing for Resource Allocation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Information Technology, Electronics and Intelligent Communication Systems (ICITEICS), Bengaluru, India, 28–29 June 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Alsadie, D. Artificial intelligence techniques for securing fog computing environments: Trends, challenges, and future directions. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 151598–151648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liang, Y.C. Deep reinforcement learning for channel and power allocation in UAV-enabled IoT systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 9–13 December 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Huang, A.; Zhang, H.; Chang, L.; Pan, J. Placement of UAV-mounted edge servers for internet of vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 10587–10601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Du, J.; Jiang, C.; Han, Z.; Alhammadi, A.; Debbah, M. Over-the-air federated learning in digital twins empowered UAV swarms. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 17619–17634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, H.; Wang, H.; Sun, W.; Sun, H. Adaptive computation offloading policy for multi-access edge computing in heterogeneous wireless networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2021, 19, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Hu, H.; Wang, X.; Guo, L.; Guo, S.; Wang, G.; Gao, X. Mobile edge computing and machine learning in the internet of unmanned aerial vehicles: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Zaheer, M.; Sanjabi, M.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. Proc. Mach. Learn. Syst. 2020, 2, 429–450. [Google Scholar]

- Yahya, M.; Maghsudi, S.; Stanczak, S. Federated learning in UAV-enhanced networks: Joint coverage and convergence time optimization. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2023, 23, 6077–6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Vilor, C.; Abdelhady, A.M.; Eltawil, A.M.; Jafarkhani, H. Multi-UAV Reinforcement Learning for Data Collection in Cellular MIMO Networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 15462–15476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Bi, W.; Zhang, A.; Gao, F. A distributed task reassignment method in dynamic environment for multi-UAV system. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 1582–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, F.; Song, T.; Lin, D. Heterogeneous multi-UAV distributed task allocation based on CBBA. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS), Beijing, China, 17–19 October 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 704–709. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Shin, H.S.; Tsourdos, A. Efficient decentralized task allocation for UAV swarms in multi-target surveillance missions. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Atlanta, GA, USA, 11–14 June 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Asad, M.; Moustafa, A.; Ito, T. Fedopt: Towards communication efficiency and privacy preservation in federated learning. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Xu, H.; Zhang, W.-A. Distributed dynamic task allocation for unmanned aerial vehicle swarm systems: A networked evolutionary game-theoretic approach. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2024, 37, 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Xu, J.; Liu, S.; Jin, Y. Federated learning on non-IID data: A survey. Neurocomputing 2021, 465, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothukuri, V.; Parizi, R.M.; Pouriyeh, S.; Huang, Y.; Dehghantanha, A.; Srivastava, G. A survey on security and privacy of federated learning. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 115, 619–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konečný, J.; McMahan, H.B.; Yu, F.X.; Richtárik, P.; Suresh, A.T.; Bacon, D. Federated learning: Strategies for improving communication efficiency. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1610.05492. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, X.; Kamp, M.; Dou, Q. Fedbn: Federated learning on non-iid features via local batch normalization. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.07623. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh, C.T.; Tran, N.; Nguyen, J. Personalized federated learning with moreau envelopes. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 21394–21405. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; He, B.; Song, D. Model-contrastive federated learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 10713–10722. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Dou, L.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Zong, Q. Multi-agent reinforcement learning-based coordinated dynamic task allocation for heterogenous UAVs. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 72, 4372–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, Q.; Xu, Y.; Qi, N.; Guan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, Z. Joint task assignment and spectrum allocation in heterogeneous UAV communication networks: A coalition formation game-theoretic approach. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2020, 20, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asheralieva, A.; Niyato, D. Game theory and Lyapunov optimization for cloud-based content delivery networks with device-to-device and UAV-enabled caching. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 10094–10110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Lu, Z.; Huang, S.; Yang, Y. Distributed DRL-based intelligent over-the-air computation in unmanned aerial vehicle swarm-assisted intelligent transportation system. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 34382–34397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).