Integration of Theoretical and Experimental Torsional Vibration Analysis in a Marine Propulsion System with Component Degradation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. International Standards for Torsional Vibration of Propeller Shafts and Gear Transmissions

3. Theoretical Torsional Vibration Calculation

3.1. Methodology

3.2. Specifications of Propulsion System

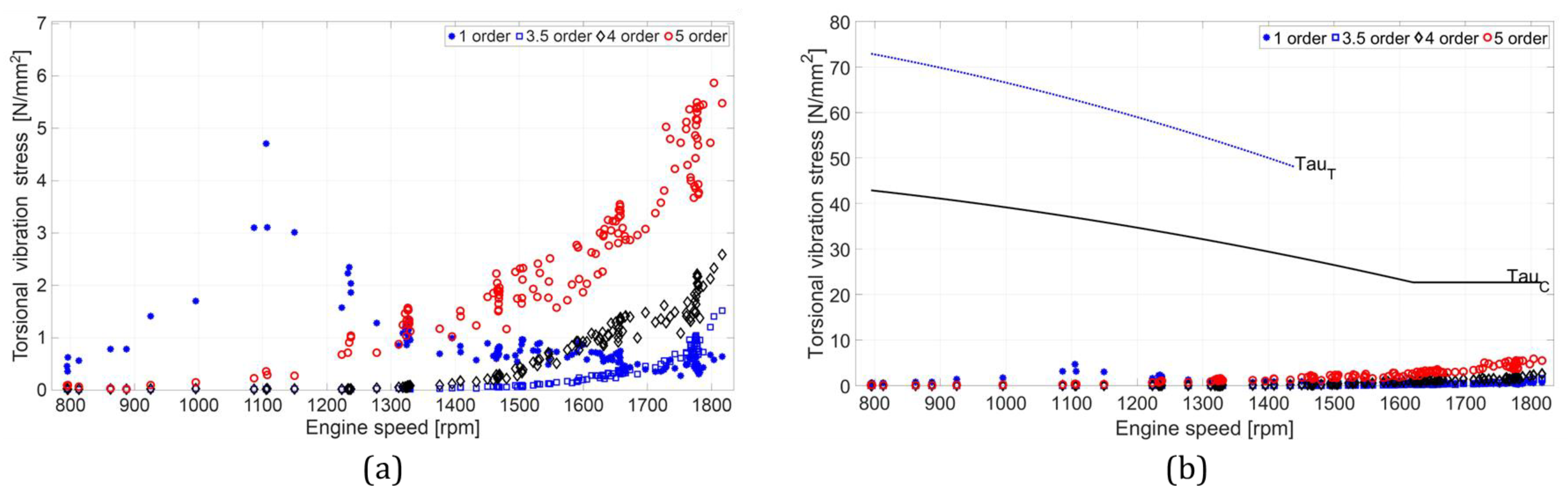

3.3. TVC Results

4. Torsional Vibration Measurement

4.1. Measurement Setup

4.2. Experiments and Results

- The ship loading condition was close to the designed nominal operating condition.

- Water depth was greater than five times the ship draught.

- Minimum turning, with the rudder angle not exceeding 2 degrees.

- Sea state 1.

- a.

- Normal Firing Steady-State Measurement

- b.

- Transient State Measurement

- 1.

- Ensure the clutch is fully disengaged. Operate the main engine at approximately 800 rpm under no load condition.

- 2.

- Engage the clutch while continuously measuring the torsional vibration and transmitted torque.

- 3.

- Maintain engagement until stable torque transmission is achieved.

- 4.

- Disengage the clutch and observe torsional vibration response during disengagement phase.

5. Root Cause Analysis

5.1. Degradation of Rubber Blocks

5.2. Degradation of Torsional Viscous Damper

5.3. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- The calculated torsional vibration of the output gear closely matched that of the propeller shaft. Therefore, measurements at the propeller shaft can be used to assess the condition of output gear, where a direct measurement is difficult. Vibration levels that satisfy propeller shaft criteria may still be critical for the gear system, highlighting the need to reference specific torsional vibration requirements for gears. This approach can be applied to propulsion systems that use gears to enhance condition monitoring and optimize maintenance strategies.

- Measured torsional vibration of the propeller shaft was below allowable limits but significantly higher than calculated values, particularly at the 5th harmonic order excited by the engine combustion process and increasing as the speed approached MCR. This suggested that torsional vibration in the gears may be critical.

- The transient torsional vibration during clutch engagements remained below, but close to, limits for gear transmissions. The vibration measured during the astern test was greater than that observed in the ahead test. The negative torque peaks, reaching an absolute value of 4.1 kNm, caused gear hammering, which increased noise, resulted in rougher gear engagement, and reduced the fatigue life of the gears. This is an important consideration, as ferries frequently alternate between ahead and astern operations, and harsh weather conditions can further amplify vibration amplitudes.

- Structural vibration at the 96th order observed in the gearbox casing did not correspond to an integer multiple of any gear mesh frequency. This indicates possible gearbox defects such as wear or misalignment. This resulted in a structural resonance of 29 m/s2, which caused the abnormal noise at MCR. However, this vibration has no remarkable effect on the structure of reduction gear as its amplitude was much smaller than the limit.

- Multiple TVC models were analyzed to identify the root cause of excessive torsional vibration. The best match to the measured data was a damper degradation model where the torsional stiffness remains at 100%, but the damping capacity drops to about 1%, corresponding to the specified values at 125 °C. An inspection confirmed oil leakage and deteriorated viscous oil quality, necessitating prompt oil replacement to improve torsional vibration behavior. Furthermore, regular inspection and maintenance of viscous dampers, along with other related components, are essential to ensuring effective torsional vibration control and the safe long-term operation of propulsion systems.

- The limitation in this study is that the torsional vibration measurement was conducted only at the propeller shaft. Expanding measurements to multiple points, such as angular velocity fluctuations before and after the reduction gear, would enable a more detailed comparison between calculated and measured results, enhancing the accuracy of the analysis.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DNV GL | Det Norske Veritas Germanischer Lloyd |

| GMF | Gear mesh frequency |

| IACS | International Association of Classification Societies |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| LR | Lloyd’s Register |

| MCR | Maximum continuous rate |

| TVC | Torsional vibration calculation |

References

- Parsons, M.G. Marine Propulsion Machinery Vibration; Marine Engineering Series; Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers: Jersey City, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Det Norske Veritas Germanischer Lloyd (DNV GL). Rules for Classification: Ships—Part 6 Chapter 2: Propulsion, Power Generation and Auxiliary Systems; DNV GL: Oslo, Norway, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Halilbeşe, A.N.; Zhang, C.; Özsoysal, O.A. Effect of coupled torsional and transverse vibrations of the marine propulsion shaft system. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2021, 20, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Lee, J.U. An experimental investigation of ship propulsion system fatigue damage during crash astern maneuver. Ocean Eng. 2024, 309, 118530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambon, A.; Moro, L. Torsional vibration analysis of diesel driven propulsion systems: The case of a polar-class vessel. Ocean Eng. 2022, 245, 110330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, Z.; Pan, B.; Wang, R.; Wang, L. Analysis of excitation source characteristics and their contribution in a 2-cylinder diesel engine. Measurement 2021, 176, 109195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S.; Guo, Y.; Lv, B.; Wang, D.; Li, W.; Shuai, Z. Analysis of torsional vibration effect on the diesel engine block vibration. Mech. Ind. 2020, 21, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Chen, Y.; Cao, H.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, H.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, C. Coupling effect of shaft torsional vibration and advanced injection angle on medium-speed diesel engine block vibration. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 154, 107624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everllence. Basic Principles of Ship Propulsion. Available online: https://www.man-es.com/docs/default-source/document-sync/basic-principles-of-ship-propulsion-eng.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Brodin, E.; Nøkleby, J.; Amini, H.; Avanesov, M.; Deinboll, M. Marine propulsion—Revised class rules for passing barred speed range. In Proceedings of the Torsional Vibration Symposium, Salzburg, Austria, 13–15 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.-H.; Pham, X.D.; Vuong, Q.D. Torsional vibration stress and fatigue strength analysis of marine propulsion shafting system based on engine operation patterns. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, N.; Zhan, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zou, L.; Pang, X. Study on torsional vibration response characteristics of marine propulsion shafting. J. Ship Res. 2024, 68, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, K.; Park, S. Estimate of the fatigue life of the propulsion shaft from torsional vibration measurement and the linear damage summation law in ships. Ocean Eng. 2015, 107, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 20283-4:2012; Mechanical Vibration—Measurement of Vibration on Ships—Part 4: Measurement and Evaluation of Vibration of the Ship Propulsion Machinery. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- Lloyd’s Register (LR). Rules and Regulations for the Classification of Ships, Part 5, Chapter 8: Shaft Vibration and Alignment; LR: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Det Norske Veritas Germanischer Lloyd (DNV GL). Rules for Classification: Ships—Part 4 Chapter 2: Shaft Vibration and Alignment; DNV GL: Oslo, Norway, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- American Bureau of Shipping (ABS). Guidance Notes on Ship Vibration; ABS: Houston, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Den Hartog, J.P. Mechanical Vibrations, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, W., Jr.; Timoshenko, S.P.; Young, D.H. Vibration Problems in Engineering; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, J.; Wen, T. A Modified Transfer Matrix Method for Modal Analysis of Stepped Rotor Assembly Applied in the Turbomolecular Pump. Shock Vib. 2022, 2022, 3692081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, R.; Jia, B.; Zhao, Z.; Jin, J. Concept and electromechanical-coupling modeling of a torsional vibration excitation method. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 236, 107709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestel, E.C.; Leckie, F.A. Matrix Methods in Elastomechanics; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Hatter, D.J. Matrix Computer Methods of Vibration Analysis; Butterworth-Heinemann: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan, P. Matrix Methods of Structural Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rui, X.; Wang, G.; Zhang, J. Transfer Matrix Method for Multibody Systems: Theory and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Zeng, X.; Liu, X.; Rui, X. Transfer matrix method for the free and forced vibration analyses of multi-step Timoshenko beams coupled with rigid bodies on springs. Appl. Math. Model. 2020, 87, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.-C.; Chen, J.-H.; Lee, A.-C. A modified transfer matrix method for the coupling lateral and torsional vibrations of symmetric rotor-bearing systems. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 289, 294–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrak, Y. Torsional Vibration Calculation Issues with Propulsion Systems; SKF Solution Factory-Marine Services-Shaft Designer: Ridderkerk, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, A.S.; Meirelles, P.S.; Zampieri, D.E. Analysis of torsional vibration in internal combustion engines: Modelling and experimental validation. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part K J. Multi-Body Dyn. 2008, 222, 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association of Classification Societies (IACS). Unified Requirement M68: Dimensions of Propulsion Shafts and Their Permissible Torsional Vibration Stresses, Rev.3; IACS: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- ClassNK. Power Transmission Systems: Amended Rules and Guidance. Rules for the Survey and Construction of Steel Ships, Part D: Machinery Installations; ClassNK: Tokyo, Japan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jáuregui-Correa, J.C.; Lozano Guzmán, A.A. Mechanical vibrations and condition monitoring. In Mechanical Vibrations and Condition Monitoring; Jáuregui-Correa, J.C., Lozano Guzmán, A.A., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2020; Chapter 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 20816-9:2020; Mechanical Vibration—Measurement and Evaluation of Machine Vibration—Part 9: Gear Units. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Polukoshko, S.; Martinovs, A.; Zaicevs, E. Influence of rubber ageing on damping capacity of rubber vibration absorber. Vibroeng. Procedia 2018, 19, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gent, A.N. Engineering with Rubber: How to Design Rubber Components; Carl Hanser Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Yang, M.; Meng, D.; Hu, R. Damping performance of the degraded fluid viscous damper due to oil leakage. Structures 2023, 48, 1609–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, K.; Park, S. Evaluation of the increased stiffness for the elastic coupling under the dynamic loading conditions in a ship. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2016, 68, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajňák, J.; Homišin, J.; Grega, R.; Kaššay, P.; Urbanský, M. The failures of flexible couplings due to self-heating by torsional vibrations–validation on the heat generation in pneumatic flexible tuner of torsional vibrations. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 119, 104977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, C. Study on the torsional stiffness and vibration response law of laminated coupling considering the effect of excess. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 222, 111739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Engine Model | DOOSAN V180TIH/M | Gearbox | HITACHI NICO MGN86EL-A |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engine type | 4-stroke, V type | Gear ratio | 3.93 |

| Nominal output | 441 kW at 1800 rpm | Application factor | 1.5 |

| Cylinder number | 10 | Coupling type | Rubber block |

| Vee angel | 90° | Continuous Rating | 617 kW at 1800 rpm |

| Bore | 128 mm | ||

| Stroke | 142 mm | Viscous damper | HASE & WREDE ASK 2060 |

| Reciprocal mass | 4.351 kg | ||

| Rotating mass | 2.303 kg | Propeller type | Fixed pitch |

| Con–rod ratio | 0.2773 | Propeller shaft dia. | 119 mm |

| Compression ratio | 15:1 | Propeller diameter | 1450 mm |

| Tensile strength | ≥850 N/mm2 | Blade number | 4 |

| Firing order | 1–6–5–10–2–7–3–8–4–9 | M.O.I. in water | 25.21 kg m2 |

| No. | Mass Name | Inertia | Torsional Stiffness | Absolute Damping | Relative Damping | Speed Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Damper ring | 0.3460 | 1 | |||

| 1–2 | (*) | (*) | 1 | |||

| 2 | Pulley | 0.2541 | 1 | |||

| 2–3 | 4.229 | 1 | ||||

| 3 | Throw No. 1 | 0.2546 | 1 | |||

| 3–4 | 2.714 | 1 | ||||

| 4 | Throw No. 2 | 0.2538 | 1 | |||

| 4–5 | 2.713 | 1 | ||||

| 5 | Throw No. 3 | 0.1592 | 1 | |||

| 5–6 | 2.721 | 1 | ||||

| 6 | Throw No. 4 | 0.2540 | 1 | |||

| 6–7 | 2.713 | 1 | ||||

| 7 | Throw No. 5 | 0.2569 | 1 | |||

| 7–8 | 4.521 | 1 | ||||

| 8 | Flywheel + disk | 2.2375 | 1 | |||

| 8–9 | rigid | 1 | ||||

| 9 | Driving ring (I1) | 1.774 | 1 | |||

| 9–10 | 6.368 | 0.00556 | 1 | |||

| 10 | Spider gear (I2) | 0.916 | 1 | |||

| 10–11 | 0.867 | 1 | ||||

| 11 | Reverse driving gear (I3) | 0.160 | 1 | |||

| 11–12 | rigid | 1 | ||||

| 12 | Reverse driven gear (I4) | 0.160 | 1 | |||

| 12–13 | rigid | 1 | ||||

| 13 | Steel plate (I8) | 0.012 | 1 | |||

| 13–14 | 12.384 | 1 | ||||

| 14 | Pinion (I10) | 0.034 | 1 | |||

| 14–15 | rigid | 1 | ||||

| 15 | Gear (I11) | 5.435 | 1 | |||

| 15–18 | 4.9999 | 1 | ||||

| 16 | Steel plate (I7) | 0.012 | 1 | |||

| 16–17 | 12.384 | 1 | ||||

| 17 | Pinion (I9) | 0.034 | 1 | |||

| 17–15 | rigid | 1 | ||||

| 18 | Output flange (I12) | 0.468 | 1:3.93 | |||

| 18–19 | rigid | 1:3.93 | ||||

| 19 | Companion flange (I13) | 0.811 | 1:3.93 | |||

| 19–20 | rigid | 1:3.93 | ||||

| 20 | ½ Propeller shaft | 0.360 | 1:3.93 | |||

| 20–21 | 0.337 | 1:3.93 | ||||

| 21 | ½ Tail shaft | 0.360 | 1:3.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vuong, Q.D.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.-U. Integration of Theoretical and Experimental Torsional Vibration Analysis in a Marine Propulsion System with Component Degradation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11423. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111423

Vuong QD, Lee J, Lee J-U. Integration of Theoretical and Experimental Torsional Vibration Analysis in a Marine Propulsion System with Component Degradation. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11423. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111423

Chicago/Turabian StyleVuong, Quang Dao, Jiwoong Lee, and Jae-Ung Lee. 2025. "Integration of Theoretical and Experimental Torsional Vibration Analysis in a Marine Propulsion System with Component Degradation" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11423. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111423

APA StyleVuong, Q. D., Lee, J., & Lee, J.-U. (2025). Integration of Theoretical and Experimental Torsional Vibration Analysis in a Marine Propulsion System with Component Degradation. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11423. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111423