Decision Framework for Asset Criticality and Maintenance Planning in Complex Systems: An Offshore Corrosion Management Case

Abstract

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

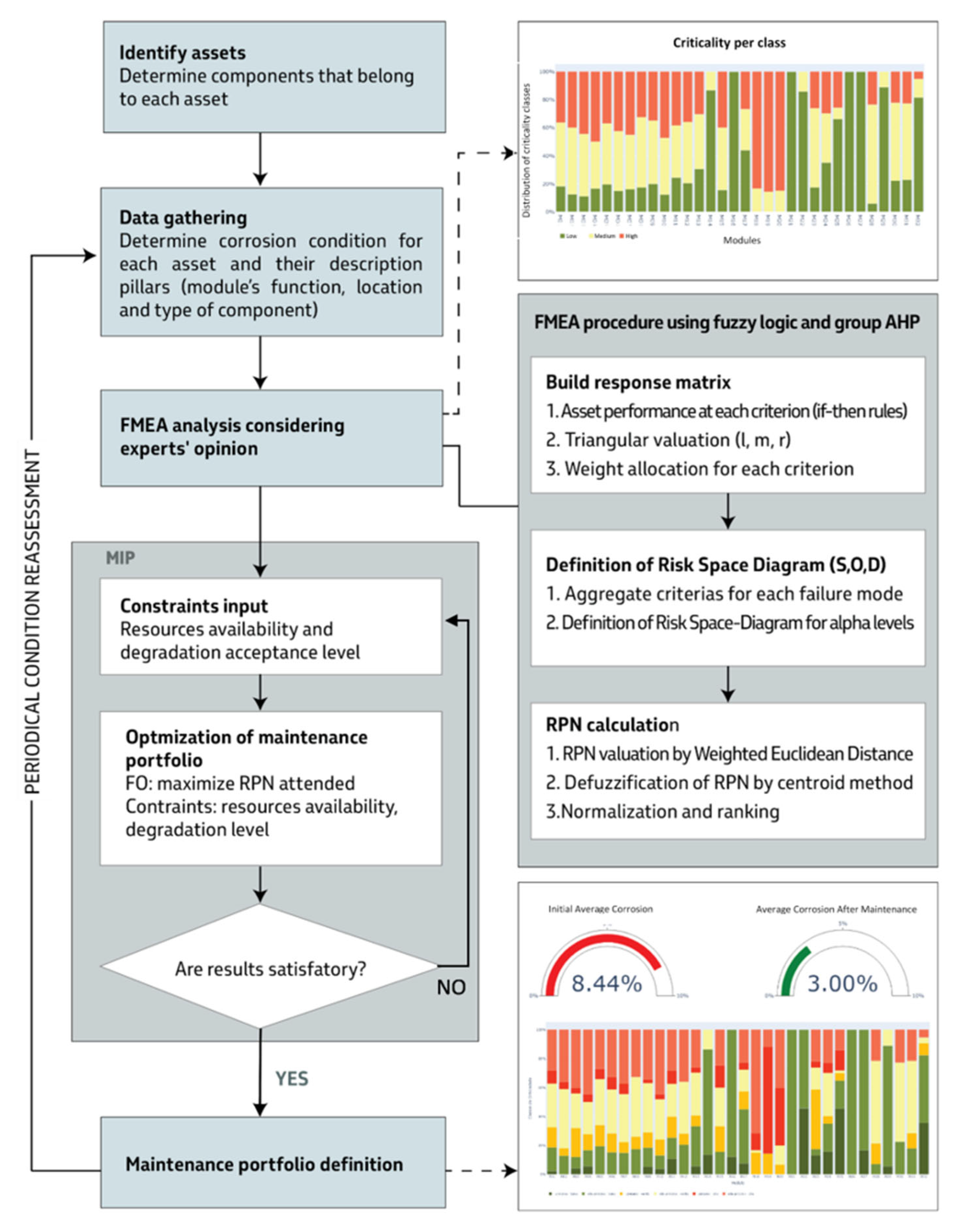

3. The Proposed Method

3.1. Preliminaries

3.2. Mathematical Model Formulation

3.2.1. AHP-Group Decision-Making Method

- (i)

- define the problem and clarify the domain of knowledge;

- (ii)

- design the decision structure from a top-down perspective, considering the objective, criteria, and set of available alternatives;

- (iii)

- construct pairwise comparison matrices for each level and its subsequent lower level. The matrix values designate relative weights;

- (iv)

- weight each level (criteria and sub-criteria) based on priority values from previous steps;

- (v)

- perform hierarchical synthesis using eigenvectors and criterion weights; and

- (vi)

- determine the consistency of comparison matrices using the eigenvalue method to calculate the consistency index (CI).

3.2.2. Algorithm of Risk Priority Number

3.2.3. Optimization Model

3.3. Framework

- H = M × S × Sys represents the complete three-tier asset hierarchy

- C = CS ∪ CO ∪ CD represents all 15 expert-validated criterion types

- R represents the complete set of expert-validated if-then rules

- g represents the fuzzy composition operator

- V = {Low, Average, High} represents the linguistic variable domain

- D represents the domain specifications for each attribute (as shown in the evaluation criteria table)

4. Application Case—An Offshore Corrosion Management Case

4.1. Asset Identification

- Module Level (M): M = {Accommodation, Naval, Production, Cargo Area, Offloading, Pipe Rack, Pull In/Out, …}

- Sector Level (S): S = {Elevation × Exposure × Plant Location} where:

- ○

- Elevation ∈ {Bottom, Centre, Top}

- ○

- Exposure ∈ {Non-exposed(0), Exposed(1)}

- ○

- Plant Location ∈ {Starboard, Port, Bow, Stern, Centre}

- System Level (Sys): Sys = {Floor, Ceiling, Bulkhead, Staircase, Guardrail, Primary Structures, Secondary Structures, Piping Support, Equipment Support, Electrical Support}

4.2. Data Gathering

- Quantitative Attributes:

- ○

- id: Unique asset identifier (integer)

- ○

- Area: Physical surface area in m2 (continuous variable)

- ○

- Corrosion: Current corrosion level as percentage (0–100%)

- ○

- Productivity: Operational efficiency coefficient (0–1 scale)

- Categorical Attributes (Expert-Defined Domains):

- ○

- Components’ system ∈ {Floor, Bulkhead, Secondary Structures, Piping Support, Primary Structures, Guardrail, …}

- ○

- Module’s function ∈ {Accommodations, Cargo Area, Offloading, Pipe Rack, Pull In/Out, …}

- ○

- Plant Location ∈ {Stern, Port, Starboard, Center, …}

- ○

- Exposure ∈ {0 (Non-exposed), 1 (Exposed)}

- ○

- Elevation ∈ {Bottom, Centre, Top} (encoded as numerical values)

4.3. FMEA Analysis

4.3.1. Criteria Selection

- Severity Criteria (CS): {Environmental impact, Production shutdown, Risk of explosion, Risk of falls, Risk of falling objects}

- Occurrence Criteria (CO): {Frequency of failure, Humidity, Atmospheric pollutants, Environmental temperature, Material degradation}

- Detection Criteria (CD): {Access to equipment, Lighting conditions, Surfaces in contact}

4.3.2. Criteria Classification

- R1: IF (Module_function ∈ {Accommodation, Naval}) THEN (Surrounding_equipment_criticality = Low)

- R4: IF (Components_system ∈ {Guardrail}) AND (Elevation ∈ {Centre, Top}) THEN (Risk_of_falls_criticality = g(High, High) = High)

- R10: IF (Exposure = Non-exposed) AND (Plant_location ∈ {Port}) THEN (Wind_exposure_criticality = g(Low, High) = Average)

4.3.3. Performance at Each Failure Parameter

4.3.4. Criticality Assessment

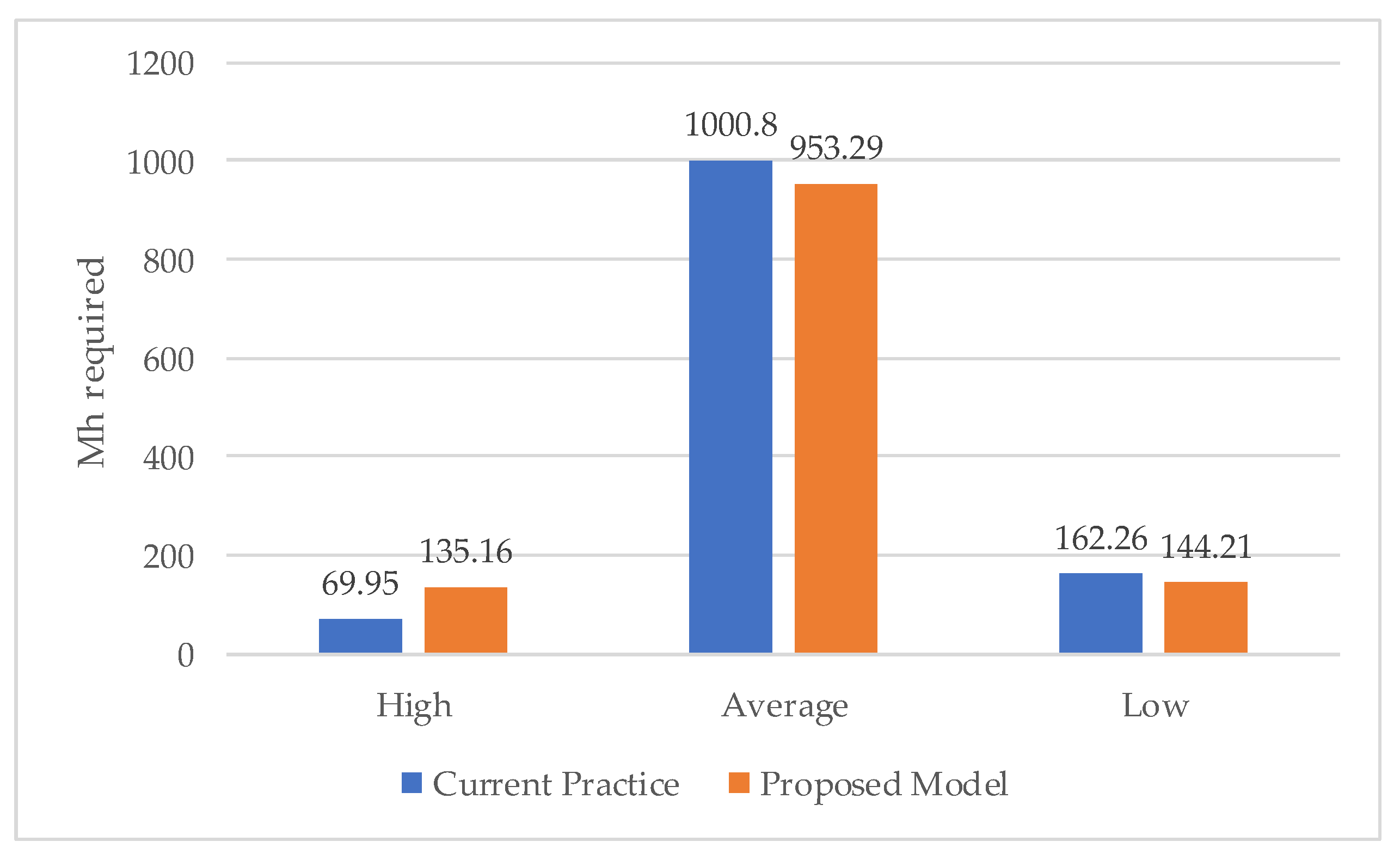

4.4. Maintenance Portfolio Optimization

5. Discussion and Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Syed, Z.; Lawryshyn, Y. Multi-criteria decision-making considering risk and uncertainty in physical asset management. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2020, 65, 104064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurin, T.A.; Rooke, J.; Koskela, L. A complex systems theory perspective of lean production. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 5824–5838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson-Cook, C.M.; Graves, T.L.; Hamada, M.S. Resource allocation for reliability of a complex system with aging components. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2009, 25, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panenka, A.; Fangue, F.M.N.; Rabe, R.; Schmidt-Bäumler, H.; Sorgatz, J. Reliability assessment of ageing infrastructures: An interdisciplinary methodology. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2020, 16, 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnayake, R.C. Application of a fuzzy inference system for functional failure risk rank estimation: RBM of rotating equipment and instrumentation. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2014, 29, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzaghi, E.; Abaei, M.M.; Abbassi, R.; Garaniya, V.; Chin, C.; Khan, F. Risk-based maintenance planning of subsea pipelines through fatigue crack growth monitoring. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2017, 79, 928–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Raza, S.A.; Ahmed, Q.; Khan, F.; Ahmed, S. A decision support tool for bi-objective risk-based maintenance scheduling of an LNG gas sweetening unit. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2019, 25, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, G.; Sadiq, R.; Tesfamariam, S. A fuzzy Bayesian belief network for safety assessment of oil and gas pipelines. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2016, 12, 874–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moan, T. Reliability-based management of inspection, maintenance and repair of offshore structures. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2005, 1, 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, S.; Charles-Owaba, O.; Johnson, A.; Omogoroye, O. A fuzzy safety control framework for oil platforms. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2006, 23, 564–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.D.; Jardine, A.K.S.; McGlynn, J. Asset Management Excellence: Optimizing Equipment Life-Cycle Decisions, 2nd ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mobley, T. An Introduction to Predictive Maintenance; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gentil, V. Corrosão, 6th ed.; LTC—Livros Técnicos e Científicos Editora Ltda: Barueri, Brazil, 2011; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, M.; Keshavarzzadeh, V.; Noshadravan, A. Reliability-based lifecycle management for corroding pipelines. Struct. Saf. 2019, 76, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G1. globo.com. ANP Interdita Navio-Plataforma com Risco de Explosão na Costa do ES|Espírito Santo. 2022. Available online: https://g1.globo.com/es/espirito-santo/noticia/2022/09/20/anp-interdita-navio-plataforma-com-risco-de-explosao-na-costa-do-es.ghtml (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Adams, R.N. Saúde E Segurança Do Trabalho Em Plataformas Offshore: Revisitando O Acidente No Fpso Cidade De São Mateus Três Anos Depois; Universidade Federal Fluminense: Niterói, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- API (American Petroleum Institute). API RP 580: Risk-Based Inspection; API Publishing Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Priyanta, D.; Siswantoro, N.; Sukandar, R.A. Determination of Maintenance Task on Rotary Equipment Using Reliability Centered Maintenance II Method. Int. J. Mar. Eng. Innov. Res. 2019, 4, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A.; Pires, C.; Lopes, I. Comparative study of the application of RCM and risk matrix for risk assessment of collaborative robots. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2019, 791, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowlan, F.S.; Heap, H.F. Reliability-Centered Maintenance; United Airlines (UAL): Chicago, IL, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Melchers, R.E. The effect of corrosion on the structural reliability of steel offshore structures. Corros. Sci. 2005, 47, 2391–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, S.; Okada, H.; Naitoh, M.; Kojima, M.; Kikura, H.; Liste, D.H. Improvement of plant reliability based on combination of prediction and inspection of wall thinning due to FAC. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2018, 337, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, H.; Tesfamariam, S.; Haider, H.; Sadiq, R. Inspection and maintenance of oil & gas pipelines: A review of policies. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2016, 13, 794–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.-F.; Li, Y.; Chen, C.-H.; He, J.-L.; Hou, T.-W.; Chen, J.-H. Advanced FMEA method based on interval 2-tuple linguistic variables and TOPSIS. Qual. Eng. 2019, 32, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, T.; Zheng, H.; Yin, L.; Deng, Y. Failure mode and effects analysis based on D numbers and TOPSIS. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2018, 34, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakhrit, A.; Djelamda, I.; Bougofa, M.; Guetarni, I.H.M.; Bouafia, A.; Chennoufi, M. Integrating fuzzy logic and multi-criteria decision-making in a hybrid FMECA for robust risk prioritization. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2024, 40, 3555–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorshidi, H.A.; Gunawan, I.; Ibrahim, M.Y. Applying UGF Concept to Enhance the Assessment Capability of FMEA. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2015, 32, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Mishra, R.P. A Failure Mode Effect and Criticality Analysis of Conventional Milling Machine Using Fuzzy Logic: Case Study of RCM. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2016, 33, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaid, A.A.A.; Ahmad, R.; Mustafa, S.A.; Mohammed, B.A. A systematic reliability-centred maintenance framework with fuzzy computational integration—A case study of manufacturing process machinery. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2024, 30, 456–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshvar, S.; Yazdi, M.; Adesina, K.A. Fuzzy smart failure modes and effects analysis to improve safety performance of system: Case study of an aircraft landing system. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2020, 36, 890–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Yan, L.; Han, M.; Gu, X. Survey of FMEA methods with improvement on performance inconsistency. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2021, 38, 1850–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemweno, P.; Pintelon, L.; De Meyer, A.; Muchiri, P.N.; Van Horenbeek, A.; Wakiru, J. A Dynamic Risk Assessment Methodology for Maintenance Decision Support. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2016, 33, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, H.; Yunusoglu, M.G.; Balaman, Ş.Y. A Dynamic Maintenance Planning Framework Based on Fuzzy TOPSIS and FMEA: Application in an International Food Company. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2015, 32, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, R.; Gao, J.; Gao, Z.; Deng, W. A novel framework for the reliability modelling of repairable multistate complex mechanical systems considering propagation relationships. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2018, 35, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; He, Y.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, A.; Han, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, W. Functional risk-oriented integrated preventive maintenance considering product quality loss for multistate manufacturing systems. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 59, 1003–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, Y.; Liao, R.; Zheng, X.; Dai, W. Integrated predictive maintenance approach for multistate manufacturing system considering geometric and non-geometric defects of products. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 228, 108793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, Z.; Xie, M.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, W. Remaining useful life prediction and predictive maintenance strategies for multi-state manufacturing systems considering functional dependence. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 210, 107560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberge, P.R. Handbook of Corrosion Engineering; McGraw-Hill Professional: Columbus, OH, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Endrenyi, J.; Aboresheid, S.; Allan, R.; Anders, G.; Asgarpoor, S.; Billinton, R.; Chowdhury, N.; Dialynas, E.; Fipper, M.; Fletcher, R.; et al. The present status of maintenance strategies and the impact of maintenance on reliability. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2001, 16, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.; As’aD, R.A. Reliability centered maintenance actions prioritization using fuzzy inference systems. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2016, 22, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Mishra, R.P.; Singhvi, P. An Application of Reliability Centered Maintenance Using RPN Mean and Range on Conventional Lathe Machine. Int. J. Reliab. Qual. Saf. Eng. 2016, 23, 1640010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiori, G.; Formentin, F.; Rampini, F.; Stepp, L.M.; Gilmozzi, R.; Hall, H.J. Reliability-centered maintenance for ground-based large optical telescopes and radio antenna arrays. In Ground-Based and Airborne Telescopes V; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014; Volume 9145, p. 91453M. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.-C.; Liu, L.; Liu, N. Risk evaluation approaches in failure mode and effects analysis: A literature review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Zheng, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, X. An interval probability-based FMEA model for risk assessment: A real-world case. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2019, 36, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, H.-W.; Liou, J.J. A novel multiple-criteria decision-making-based FMEA model for risk assessment. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 73, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Zhao, Z.-J.; Huang, C.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Wang, H.-T.; Yang, Y.-J. Application of reliability-centered maintenance in metro door system. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 186167–186174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamayleh, A.; Awad, M.; Abdulla, A.O. Criticality-based reliability-centered maintenance for healthcare. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2019, 26, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrifaey, M.; Hong, T.S.; As’arry, A.; Supeni, E.E.; Ang, C.K. Optimization and selection of maintenance policies in an electrical gas turbine generator based on the hybrid reliability-centered maintenance (RCM) model. Processes 2020, 8, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catelani, M.; Ciani, L.; Galar, D.; Patrizi, G. Optimizing Maintenance Policies for a Yaw System Using Reliability-Centered Maintenance and Data-Driven Condition Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 6241–6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.S.; Bewoor, A.K. Optimization of maintenance strategies for steam boiler system using reliability-centered maintenance (RCM) model—A case study from Indian textile industries. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2022, 39, 1745–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawulich, B.B. Participant Observation as a Data Collection Method. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2005, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Serv. Sci. 2008, 1, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulgader, F.S.; Eid, R.; Rouyendegh, B.D. Development of decision support model for selecting a maintenance plan using a fuzzy MCDM approach: A theoretical framework. Appl. Comput. Intell. Soft Comput. 2018, 2018, 9346945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J. Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method. Omega 2015, 53, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de FSM Russo, R.; Camanho, R. Criteria in AHP: A systematic review of literature. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 55, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, E.; Peniwati, K. Aggregating individual judgments and priorities with the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1998, 108, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. Decision Making Using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP); A Step by Step Approach Hamed Taherdoost To cite this ver-sion: HAL Id: hal-02557320 Decision Making Using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP); A Step by Step Approach. J. Econ. Manag. Syst. 2017, 2, 244–246. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, B.L.; Wasil, E.A.; Harker, P.T. The Analytic Hierarchy Process: Applications and Studies, 1st ed.; Springer: Heidelberg/Berlin, Germany, 1989; Volume 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xu, B.; Chen, F.; Hao, Q.; Zhu, X.; Jia, Y. A new failure mode and effects analysis model of CNC machine tool using fuzzy theory. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Information and Automation, ICIA 2010, Harbin, China, 20–23 June 2010; pp. 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiado, R.G.G.; Rios, M.P.; Martins, G.C.; Netto, P.I.; Elmas, F.R. Fuzzy Criticality Assessment of Systems External Corrosion Risks in the Petroleum Industry—A Case Study. Ind. Eng. Oper. Manag. 2021, 367, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-T. The extension of fuzzy QFD: From product planning to part deployment. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 11131–11144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayağ, Z.; Özdemir, R.G. Evaluating machine tool alternatives through modified TOPSIS and alpha-cut based fuzzy ANP. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-C.T.; Wang, Y.-C.; Chiu, M.-C. An efficient approximating alpha-cut operations approach for deriving fuzzy priorities in fuzzy multi-criterion decision-making. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 139, 110238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, C.O. Modelagem e Otimização do Planejamento da Produção de uma Refinaria de Petróleo. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Faculdade de Engenharia Química, São Paulo, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- de Miranda, M.A. Um Modelo de Otimização Inteira Mista na Programação de Produção de Mangueiras Hidráulicas. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” Campos de Guaratinguetá, São Paulo, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Biegler, L.T.; Grossmann, I.E. Retrospective on optimization. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2004, 28, 1169–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appa, G.M. The transportation problem and its variants. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1973, 24, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeb, J.; Leavengood, S. Transportation Problem: A Special Case. In Performance Excellence in the Woord Products Industry: Operations Research; Oregon State University: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2022; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chen-yi, H.; Ke-ting, C.; Gwo-hshiung, T. FMCDM with Fuzzy DEMATEL Approach for Customers’ Choice Behavior Model. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2007, 9, 236–246. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, M.J.; Morse, J.M. Situating and Constructing Diversity in Semi-Structured Interviews. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2015, 2, 2333393615597674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stemler, S.E. A Comparison of Consensus, Consistency, and Measurement Approaches to Estimating Interrater Reliability. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2004, 9, 1531–7714. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.; Vargas, L. Models, methods, concepts & applications of the analytic hierarchy process. In Driven Demand and Operations Management Models; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossadnik, W.; Schinke, S.; Kaspar, R.H. Group Aggregation Techniques for Analytic Hierarchy Process and Analytic Network Process: A Comparative Analysis. Group Decis. Negot. 2015, 25, 421–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grošelj, P.; Stirn, L.Z.; Ayrilmis, N.; Kuzman, M.K. Comparison of some aggregation techniques using group analytic hierarchy process. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 2198–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DNV-GL-RP-C302; Risk Based Corrosion Management. DNV: Bærum, Norway, 2013.

- ASTM D610-1; Standard Test Method for Evaluating Degree of Rusting on Painted Steel Surfaces. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2001.

- ABNT NBR ISO 4628-3:2015; Tintas e Vernizes—Avaliação da Degradação de Revestimento—Designação da Quantidade e Tamanho dos Defeitos e da Intensidade de Mudanças Uniformes na Aparência. (Paints and Varnishes—Evaluation of Degradation of Coatings). ABNT: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2015.

| Experience with External Corrosion Management | ||

|---|---|---|

| None | 1 | 6% |

| Less than 5 years | 2 | 13% |

| 5 to 10 years | 5 | 31% |

| More than 10 years | 8 | 50% |

| Experience with Inspection Activities | ||

| None | 6 | 38% |

| Less than 5 years | 1 | 6% |

| 5 to 10 years | 2 | 13% |

| More than 10 years | 7 | 44% |

| Experience with Maintenance Activities | ||

| None | 2 | 13% |

| Less than 5 years | 4 | 25% |

| 5 to 10 years | 4 | 25% |

| More than 10 years | 6 | 38% |

| Expert | Operating Unit | Position | Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Senior technician | Experience in corrosion inspection |

| 2 | 4 | Senior level | Experience in corrosion management |

| 3 | 3 | Senior level | Experience in corrosion research and corrosion management |

| 4 | 1 | Production engineer | Maintenance team leader |

| 5 | 3 | Master technician | Experience in corrosion inspection |

| 6 | Corporate | Master level | Experience in asset integrity |

| 7 | 2 | Senior level | Experience in corrosion management |

| 8 | 4 | Master technician | Experience in corrosion inspection |

| SL SR | SL SR | SL SR | |||

| OL OR | OL OR | OL OR | |||

| DL DR | DL DR | DL DR |

| Linguistic Variable | Universe of Discourse | Linguistic Values | Triangular Fuzzy Numbers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corrosion assessment criteria | 0–1 | Low | (0; 0.25; 0.5) |

| Average | (0.25; 0.5; 0.75) | ||

| High | (0.5; 0.75; 1) |

| Expert | S_O | S_D | O_D | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0.02927491 |

| 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0.02619547 |

| 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0.35067212 |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 0.49036376 |

| 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0.02619547 |

| 6 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0.24540649 |

| 7 | 2 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.33217336 |

| 8 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0.34442475 |

| 9 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0.35067212 |

| 10 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0.09114386 |

| 11 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0.34442475 |

| 12 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 0.47131007 |

| 13 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 0.49036376 |

| 14 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 0.70993915 |

| 15 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0.35067212 |

| 16 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 0.47131007 |

| Expert 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | O | D | Weights | |

| S | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0.6232 |

| O | 0.333 | 1 | 2 | 0.2395 |

| D | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.1373 |

| CR = 0.0293 | ||||

| Expert 2 | ||||

| S | O | D | Weights | |

| S | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.5485 |

| O | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.2409 |

| D | 0.333 | 1 | 1 | 0.2106 |

| CR = 0.0262 | ||||

| Expert 3 | ||||

| S | O | D | Weights | |

| S | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.5485 |

| O | 0.333 | 1 | 1 | 0.2106 |

| D | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.2409 |

| CR = 0.0262 | ||||

| Expert 4 | ||||

| S | O | D | Weights | |

| S | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0.6551 |

| O | 0.25 | 1 | 2 | 0.2114 |

| D | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.1335 |

| CR = 0.0911 | ||||

| Aggregated Weights | ||||

| S | 0.5989 | |||

| O | 0.2259 | |||

| D | 0.1752 | |||

| CR = 0.1297 | ||||

| id | Area | Corrosion | Productivity | Components’ System | Modulus’ Function | Plant Location | Exposure | Elevation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 491.86 | 10.00% | 0.3 | Floor | Accommodations | Stern | 1 | 53,110 |

| 1 | 41.48 | 0.10% | 0.15 | Bulkhead | Accommodations | Stern | 1 | 53,110 |

| 54 | 7.93 | 3.00% | 0.1 | Secondary Structures | Accommodations | Port | 0 | 31,380 |

| 55 | 307.18 | 10.00% | 0.3 | Floor | Cargo Aerea | Starboard | 1 | 35,920 |

| 56 | 32.12 | 0.10% | 0.08 | Piping Support | Cargo Aerea | Starboard | 1 | 35,920 |

| 57 | 179.07 | 0.30% | 0.15 | Primary Structures | Cargo Aerea | Starboard | 1 | 35,920 |

| 91 | 9.62 | 50.00% | 0.1 | Guardrail | Offloading | Centre | 1 | 35,900 |

| 92 | 128.3 | 16.00% | 0.08 | Piping Support | Offloading | Centre | 1 | 35,900 |

| 93 | 329.71 | 16.00% | 0.15 | Primary Structures | Offloading | Centre | 1 | 35,900 |

| 129 | 109.97 | 33.00% | 0.3 | Floor | Pipe Rack | Centre | 1 | 35,900 |

| 130 | 51.12 | 0.30% | 0.1 | Guardrail | Pipe Rack | Centre | 1 | 35,900 |

| 131 | 237.06 | 10.00% | 0.08 | Piping Support | Pipe Rack | Centre | 1 | 35,900 |

| 132 | 1881.02 | 16.00% | 0.15 | Primary Structures | Pipe Rack | Centre | 1 | 35,900 |

| 172 | 185.14 | 16.00% | 0.3 | Floor | Pull In/Out | Centre | 1 | 35,900 |

| 173 | 42.75 | 10.00% | 0.1 | Guardrail | Pull In/Out | Centre | 1 | 35,900 |

| 174 | 295.31 | 1.00% | 0.08 | Piping Support | Pull In/Out | Centre | 1 | 35,900 |

| Dimension | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Factors | S | O | D |

| Location | Surrounding equipment | ✔ | ||

| Risk of falls | ✔ | |||

| Risk of falling objects | ✔ | |||

| Wind exposure | ✔ | |||

| Lighting conditions | ✔ | |||

| Access to equipment | ✔ | |||

| Component information | Environmental impact | ✔ | ||

| Risk of explosion | ✔ | |||

| Production shutdown | ✔ | |||

| Surfaces in contact | ✔ | |||

| Material | ✔ | |||

| Corrosive medium information | Humidity | ✔ | ||

| Atmospheric pollutants | ✔ | |||

| Sun/ rain exposure | ✔ | |||

| Environmental temperature | ✔ | |||

| Influence of time | Failure frequency | ✔ | ||

| Factor | Evaluation Criteria | If-Then Rule for Criticality Classification |

|---|---|---|

| Surrounding equipment | Module’s function | [Low] Accommodation modules; [Average] Naval modules; [High] Production modules. |

| Environmental impact | Components’ system | [Low] Floor/Ceiling/Bulkhead/Staircase/Guardrail; [Average] Electrical supports/Structures; [High] Piping supports/Equipment supports; |

| Risk of explosion | Module’s function | [Low] Accommodation and naval modules; [Average] Production modules without gas processing; [High] Production modules with gas processing. |

| Risk of falls | Components’ system Elevation | Components’ system: [Low] Systems different from Guardrail; [High] Guardrail Elevation: [Low] Bottom; [High] Centre, Top Combination: [Low] Elevation [Low] + Components’ system [Low]; [Average] Elevation [Low] + Components’ system [High] or Elevation [High] + Components’ system [Low]; [High] Elevation [High] + Components’ system [High] |

| Production shutdown | Module’s function Components’ system | Module’s function: [Low] Accommodation and Naval modules; [High] Production modules. Components’ system: [Low] Floor/Ceiling/Bulkhead/Staircase/Guardrail; [High] Structures/Supports. Combination: [Low] Module’s function [Low] + Components’ system [Low]; [Average] Module’s function [Low] + Components’ system [High] or Module’s function [High] + Components’ system [Low]; [High] Module’s function [High] + Components’ system [High] |

| Humidity | Exposure | [Low] Non exposed; [High] Exposed |

| Atmospheric pollutants | Elevation | [Low] Top; [Average] Centre; [High] Bottom |

| Frequency of failure | Components’ system | [Low] Piping Support/Equipment Support/Ceiling; [Average] Electrical support/Primary Structures/Secondary Structures; [High] Floor/Guardrail /Bulkhead/Staircase |

| Sun/rain exposure | Exposure | [Low] Non exposed; [High] Exposed |

| Wind exposure | Exposure Plant location | Exposure: [Low] Non exposed; [High] Exposed Plant location: [Low] Starboard, bow, stern, centre; [High] Port Combination: [Low] Exposure [Low] + Plant location [Low]; [Average] Exposure [Low] + Plant location [High] or Exposure [High] + Plant location [Low]; [High] Exposure [High] + Plant location [High] |

| Environmental temperature | Module’s function | [Low] Modules without heat activity; [High] Modules with heat activity |

| Lighting conditions | Exposure | [Low] Exposed; [High] Non-exposed |

| Access to equipment | Module’s function | [Low] All modules except the ones listed as high criticality; [High] Pipe Rack/Pump House/Automation and Electrical/Riser Pipe Rack/Fenders and bollards/Flare System/Engine Room/Bosun’s Store/Cranes/Essential equipment deck |

| Risk of falling objects | Components’ system Elevation | Components’ system: [Low] Systems different from Supports; [High] Supports Elevation: [Low] Bottom, Centre; [High] Top Combination: [Low] Elevation [Low] + Components’ system [Low]; [Average] Elevation [Low] + Component’s system [High] or Elevation [High] + Components’ system [Low]; [High] Elevation [High] + Components’ system [High] |

| Material | Components’ system | [Low] Guardrail; [Average] Primary structures/Floor/Ceiling/Bulkhead; [High] Secondary structures/Supports/Staircase |

| Surfaces in contact | Components’ system | [Low] Floor/Ceiling/Bulkhead/Staircase/Guardrail; [Average] Structures, Electrical support; [High] Piping and equipment supports |

| Assets | Components’ System | Modulus’ Function | Plant Location | Exposure | Elevation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Piping Support | Pipe Rack | Centre | 1 | Bottom |

| 2 | Secondary Structures | Cargo Area | Starboard | 0 | Bottom |

| 3 | Primary Structures | Offloading | Centre | 1 | Bottom |

| Factors | Asset 1 | Asset 2 | Asset 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | Surrounding equipment | High | Average | High |

| Environmental impact | High | Average | Average | |

| Risk of explosion | High | Low | Average | |

| Risk of falls | Low | Low | Low | |

| Production shutdown | High | Average | High | |

| Risk of falling objects | Average | Low | Low | |

| O | Atmospheric pollutants | High | High | High |

| Wind exposure | Average | Low | Average | |

| Environmental temperature | High | Low | Low | |

| Humidity | High | Low | High | |

| Frequency of failure | Low | Average | Average | |

| Sun/rain exposure | High | Low | High | |

| Surfaces in contact | High | Average | Average | |

| Material | High | High | Average | |

| D | Lighting conditions | Low | High | Low |

| Access to equipment | High | Low | Low |

| RPN Dimension | Factor | Weights—Experts | Weight Aggregation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp 1 | Exp 2 | Exp 3 | Exp 4 | Exp 5 | Exp 6 | Exp 7 | Exp 8 | Avg | Norm | ||

| S | Surrounding equipment | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.17 |

| Environmental impact | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.17 | |

| Risk of explosion | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.19 | |

| Risk of falls | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.20 | |

| Production shutdown | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.11 | |

| Risk of falling objects | - | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.19 | - | 0.22 | - | 0.17 | 0.16 | |

| O | Atmospheric pollutants | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.11 |

| Wind exposure | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.12 | |

| Environmental temperature | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.10 | |

| Humidity | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.11 | |

| Frequency of failure | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.40 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.17 | |

| Sun/rain exposure | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.13 | |

| Surfaces in contact | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.14 | - | 0.14 | 0.10 | |

| Material | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.15 | |

| D | Lighting conditions | 0.58 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.47 | - | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.43 |

| Access to equipment | 0.42 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.57 | |

| Asset 1 | Asset 2 | Asset 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfa = 0 | RPNiL | 0.356 | 0.142 | 0.231 |

| RPNiR | 0.833 | 0.611 | 0.739 | |

| Alfa = 0.5 | RPNiL | 0.480 | 0.264 | 0.351 |

| RPNiR | 0.709 | 0.486 | 0.601 | |

| Alfa = 1 | RPNiL | 0.605 | 0.388 | 0.473 |

| RPNiR | 0.586 | 0.363 | 0.466 | |

| RPN | 0.595 | 0.376 | 0.477 | |

| Normalised RPN | 0.690 | 0.251 | 0.453 | |

| Category | High | Low | Average |

| AHP | Same Weights | 10% More for S | 10% More for O | 10% More for D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHP | 1 | 0.9976 | 0.9931 | 0.9835 | 0.997 |

| Same Weights | 0.9976 | 1 | 0.9951 | 0.9843 | 0.9982 |

| 10% more for S | 0.9931 | 0.9951 | 1 | 0.9817 | 0.9965 |

| 10% more for O | 0.9835 | 0.9843 | 0.9817 | 1 | 0.9846 |

| 10% more for D | 0.997 | 0.9982 | 0.9965 | 0.9846 | 1 |

| Components’ System | Productivity (m2/mh) |

|---|---|

| Floor | 0.3 |

| Bulkhead | 0.15 |

| Staircase | 0.1 |

| Guardrail | 0.1 |

| Piping Support | 0.08 |

| Primary Structures | 0.15 |

| Electrical Support | 0.1 |

| Equipment Support | 0.1 |

| Secondary Structures | 0.1 |

| Ceiling | 0.1 |

| id | mh | Corrosion | RPN |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1553.50 | 16.00% | 0.200 |

| 2 | 1373.00 | 1.00% | 0.245 |

| 3 | 793.60 | 1.00% | 0.376 |

| 4 | 4674.88 | 10.00% | 0.266 |

| 5 | 366.59 | 33.00% | 0.496 |

| 6 | 511.24 | 0.30% | 0.555 |

| 7 | 2963.29 | 10.00% | 0.690 |

| 8 | 12,540.15 | 16.00% | 0.575 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rios, M.P.; Kaiser, B.S.; Caiado, R.G.G.; Ivson, P.; Roehl, D. Decision Framework for Asset Criticality and Maintenance Planning in Complex Systems: An Offshore Corrosion Management Case. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10407. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910407

Rios MP, Kaiser BS, Caiado RGG, Ivson P, Roehl D. Decision Framework for Asset Criticality and Maintenance Planning in Complex Systems: An Offshore Corrosion Management Case. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(19):10407. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910407

Chicago/Turabian StyleRios, Marina Polonia, Bruna Siqueira Kaiser, Rodrigo Goyannes Gusmão Caiado, Paulo Ivson, and Deane Roehl. 2025. "Decision Framework for Asset Criticality and Maintenance Planning in Complex Systems: An Offshore Corrosion Management Case" Applied Sciences 15, no. 19: 10407. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910407

APA StyleRios, M. P., Kaiser, B. S., Caiado, R. G. G., Ivson, P., & Roehl, D. (2025). Decision Framework for Asset Criticality and Maintenance Planning in Complex Systems: An Offshore Corrosion Management Case. Applied Sciences, 15(19), 10407. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910407