The Role of Visual Attention and Quality Cues in Consumer Purchase Decisions for Fresh and Cooked Beef: An Eye-Tracking Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Visual Attention for Food

2.2. Quality and Visual Cues for Foods

2.3. The Relationship Between Eye Tracking and Packaging in Consumer Research

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Data

3.2. Visual Attention—Eye Tracking

- Time to First Fixation: This refers to the elapsed time until the user’s gaze first fixates on a specific area of interest. A shorter time indicates that the visual characteristics of the area are more effective in capturing attention. This metric is particularly valuable when analyzing attention to a specific target [1].

- Fixation Duration: This metric captures the total time and average location of a sequence of fixations within a designated area of interest. It may include multiple fixations and short saccades between them. The fixation sequence is considered complete when the gaze moves outside the area of interest [1].

- Number of Fixations (Visits) on an Area of Interest: A higher number of fixations suggests that the area holds greater significance for the viewer. This measure is closely related to fixation duration and helps assess the total number of fixations in tasks of varying lengths. The number of times an element is fixated on reflects its perceived importance [69,70].

3.3. Data Analysis—Logit Model

4. Results

4.1. Participant’s Profile

4.2. Visual Attention—Fresh Beef

- First Fixation (Table 2)

- Total Fixation (Table 2)

- Total Number of Fixations (Table 2)

4.3. Visual Attention—Cooked Beef

- First Fixation (Table 3)

- Total Fixation (Table 3)

- Total Number of Fixations (Table 3)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

- BREED

| Non-Breed | Nellore Breed | Angus Breed |

| Undefined origin | Originating from India | Originating from Scotland |

| Undefined hardiness | It is the hardiest breed | It is a less hardy breed |

| Undefined heat tolerance | Breed with high heat tolerance | Breed with low heat tolerance |

| Represents 10% of the total cattle herd in Brazil | Represents 80% of the total cattle herd in Brazil. | Represents 10% of the total cattle herd in Brazil. |

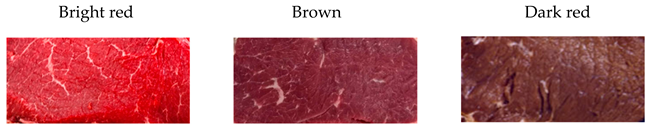

- COLOR

- MARBLING

References

- Barreto, A.M. Eye tracking como método de investigação aplicado às ciências da comunicação. Rev. Comun. 2012, 1, 168–186. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, H.; Lee, Y.; Kim, S. The influence of visual attention on consumer choice in online grocery shopping: An eye-tracking study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6347. [Google Scholar]

- Font-I-Furnols, M.; Guerrero, L. Consumer preference, behavior and perception about meat and meat products: An overview. Meat Sci. 2014, 98, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.E.; Solomon, M.B.; Lynch, M.P.; Nath, R. Physical and sensory characteristics of selected enhanced beef muscles. Meat Sci. 2005, 71, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Troy, D.J.; Kerry, J.P. Consumer perception and the role of science in the meat industry. Meat Sci. 2010, 86, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armel, C.; Beaumel, A.; Rangel, A. Biasing simple choices by manipulating relative visual attention. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2008, 3, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosavljevic, M.; Navalpakkam, V.; Koch, C.; Rangel, A. Relative visual saliency differences induce sizable bias in consumer choice. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malheiros, B.A.; Spers, E.E.; da Silva, H.M.R.; Contreras-Castillo, C.J. Southeast Brazilian Consumers’ Involvement and Willingness to Pay for Quality Cues in Fresh and Cooked Beef. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2022, 28, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebollar, R.; Lidón, I.; Martín, J.; Puebla, M. The identification of viewing patterns of chocolate snack packages using eye-tracking techniques. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenko, A.; Schifferstein, H.N.J.; Hekkert, P. Shifts in sensory dominance between various stages of user–product interactions. Appl. Ergon. 2010, 41, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Leins-Hess, R.; Keller, C. Which front-of-pack nutrition label is the most efficient one? The results of an eye-tracker study. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, R.B.; Silveira, D.S.; Brito, V.A.; Lopes, C.S. A systematic literature review on the usage of eye-tracking in understanding process models. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2021, 27, 346–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialkova, S.; Grunert, K.G.; Trijp, H.V. From desktop to supermarket shelf: Eye-tracking exploration on consumer attention and choice. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 81, 103839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.D.; Wang, Y.; Sheng, H.; Kalliny, M.; Minor, M. Escaping the corner of death? An eye-tracking study of reading direction influence on attention and memory. J. Consum. Mark. 2017, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchowski, A.T. Eye Tracking Methodology: Theory and Practice; Springer: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mundel, J.; Huddleston, P.; Behe, B.; Sage, L.; Latona, C. An eye tracking study of minimally branded products: Hedonism and branding as predictors of purchase intentions. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2018, 27, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentus, K.; Ploom, K.; Mehine, T.; Koiv, M.; Tempel, A.; Kuusik, R. Mobile and stationary eye tracking comparison—Package design and in-store results. J. Consum. Mark. 2020, 37, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, F.A.D.; Spers, E.E.; de Lima, L.M. Self-esteem and visual attention in relation to congruent and non-congruent images: A study of the choice of organic and transgenic products using eye tracking. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 84, 103938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, R.; Mccormick, H. Attention and behaviour on fashion retail websites: An eye-tracking study. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 35, 2219–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manippa, V.; Van der Laan, L.N.; Brancucci, A.; Smeets, P.A.M. Health body priming and food choice: An eye tracking study. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 72, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialkova, S.; Grunert, K.G.; Trijp, H.V. Standing out in the crowd: The effect of information clutter on consumer attention for front-of-pack nutrition labels. Food Policy 2013, 41, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navalpakkam, V.; Kumar, R.; Li, L.; Sivakumar, D. Attention and selection in online choice tasks. In Proceedings of the User Modeling, Adaptation, and Personalization: 20th International Conference, UMAP 2012, Montreal, QC, Canada, 16–20 July 2012; pp. 200–211. [Google Scholar]

- Peschel, A.O.; Orquin, J.L.; Loose, S.M. Increasing consumers’ attention capture and food choice through bottom-up effects. Appetite 2019, 132, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialkova, S.; Trijp, H.V. An efficient methodology for assessing attention to and effect of nutrition information front of pack. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.G.; Hand, C.J. Motivation determines Facebook viewing strategy: An eye movement analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 56, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedel, M.; Pieters, R. A review of eye-tracking research in marketing. Rev. Mark. Res. 2008, 4, 123–147. [Google Scholar]

- Ares, G.; Giménez, A.; Bruzzone, F.; Vidal, L.; Antúnez, L.; Maiche, A. Consumer Visual Processing of Food Labels: Results from an Eye-Tracking Study. J. Sens. Stud. 2013, 28, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banović, M.; Polymeros, C.; Grunert, K.G.; Rosa, P.J.; Gamito, P. The effect of fat content on visual attention and choice of red meat and differences across gender. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 52, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Laan, L.N.; Papies, E.K.; Hooge, I.T.C.; Smeets, P.A.M. Goal-Directed Visual Attention Drives Health Goal Priming: An Eye-Tracking Experiment. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayner, K. Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 372–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, K. Eye movements and attention in reading, scene perception, and visual search. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2009, 62, 1457–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Leiva, F.; Faísca, L.M.; Ramos, C.M.Q.; Correia, M.B.; Sousa, C.M.R.; Bouhachi, M. The influence of banner position and user experience on recall. The mediating role of visual attention. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2021, 25, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colourado, D.A.; Taba, M.C.; Parra, H.C. Las etiquetas nutricionales: Una mirada desde el consumidor. Rev. En-Contexto 2015, 3, 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, H.D. O estudo do neuromarketing como ferramenta de percepção da reação dos consumidores. Rev. Tecnol. Fatec Am. 2016, 3, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Kuo, F. An eye-tracking investigation of internet consumers’ decision deliberateness. Internet Res. 2011, 21, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.R.C.S.; Braga, L.V.M.; Anastácio, L.R. Coexistence of high content of critical nutrients and claims in food products targeted at Brazilian children. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2023, 41, 2021355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacintho, C.L.A.B.; Jardim, P.C.B.V.; Sousa, A.L.L.; Jardim, T.S.V.; Souza, W.K.S.B. Brazilian food labeling: A new proposal and its impact on consumer understanding. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 40, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G. Future and consumer lifestyles with regard to meat consumption. Meat Sci. 2006, 74, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhera, D.; Capaldi-Phillips, E.D. A review of visual cues associated with food on food acceptance and consumption. Eat. Behav. 2014, 15, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imram, N. The role of visual cues in consumer perception and acceptance of a food product. Nutr. Food Sci. 1999, 99, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboah, J.; Lees, N. Consumers use of quality cues for meat purchase: Research trends and future pathways. Meat Sci. 2020, 166, 108142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballco, P.; Gracia, A. An extended approach combining sensory and real choice experiments to examine new product attributes. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 80, 103830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morquecho-Campos, P.; Graaf, K.; Boesveldt, S. Smelling our appetite? The influence of food odors on congruent appetite, food preferences and intake. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 85, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strydom, P.; Burrow, H.; Polkinghorne, R.; Thompson, J. Do demographic and beef eating preferences impact on South African consumers’ willingness to pay (WTP) for graded beef? Meat Sci. 2019, 150, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijk, R.A.; Kaneko, D.; Dijksterhuis, G.B.; Zoggel, M.V.; Schiona, I.; Visalli, M.; Zandastra, E.H. Food perception and emotion measured over time in-lab and in-home. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 75, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.; Melo, O.; Larraín, R.; Fernández, M. Valuation of observable attributes in differentiated beef products in Chile using the hedonic price method. Meat Sci. 2019, 158, 107881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonoda, Y.; Oishi, K.; Chomei, Y.; Hirooka, H. How do human values influence the beef preferences of consumer segments regarding animal welfare and environmentally friendly production? Meat Sci. 2018, 146, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgogno, M.; Favotto, S.; Corazzin, M.; Cardello, A.V.; Piasentier, E. The role of product familiarity and consumer involvement on liking and perceptions of fresh meat. Meat Sci. 2015, 44, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerding, S.G.H.; Gentz, M.; Altmann, B.; Meier-Dinkel, L. Beef quality labels: A combination of sensory acceptance test, stated willingness to pay, and choice-based conjoint analysis. Appetite 2018, 127, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, B.; Mao, Y.; Coombs, C.; Van de Ven, R.J.; Hopkins, D.J. Relationship between colourimetric (instrumental) evaluation and consumer-defined beef colour acceptability. Meat Sci. 2016, 121, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, P.; Sun, D.W.; Allen, P.; Bradon, K.; White, A.M. Correlation of consumer assessment of longissimus dorsi beef palatability with image colour, marbling and surface texture features. Meat Sci. 2010, 84, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chonpracha, P.; Ardoin, R.; Gao, Y.; Waimaleongora-ek, P.; Tuuri, G.; Prinyawiwatkul, W. Effects of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Visual Cues on Consumer Emotion and Purchase Intent: A Case of Ready-to-Eat Salad. Foods 2020, 9, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcellos, M.D.; Aguiar, L.K.; Ferreira, G.C.; Vieira, L.M. Beef consumption in Brazil: Consumer behavior and environmental considerations. Meat Sci. 2019, 156, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Instrução normativa nº 22, de 24 de novembro de 2005. In Aprova o Regulamento Técnico Para Rotulagem de Produto de Origem Animal Embalado; Diário Oficial da União: Brasília, Brasil, 2005; seção 1.

- Chow, I.H.S.; Lau, V.P.; Lo, T.W.C.; Sha, Z.; Yun, H. Service quality in restaurant operations in China: Decision- and experiential-oriented perspectives. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 698–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Roose, G. Visual design cues impacting food choice: A review and future research agenda. Foods 2020, 9, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallez, L.; Qutteina, Y.; Raedschelders, M.; Boen, F.; Smits, T. That’s My Cue to Eat: A Systematic Review of the Persuasiveness of Front-of-Pack Cues on Food Packages for Children vs. Adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coucke, N.; Vermeir, I.; Slabbinck, H.; Kerckhove, A.V. Show Me More! The Influence of Visibility on Sustainable Food Choices. Foods 2019, 8, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, S.; Haasova, S.; Florack, A. Fifty shades of food: The influence of package colour saturation on health and taste in consumer judgments. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 37, 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuster, I.; Vila, N.; Sarabia, F. Food packaging cues as vehicles of healthy information: Visions of millennials (early adults and adolescents). Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolan, K.J.; Breslin, G.; Hanna, D.; Gallagher, A.M. Attentional bias to food-related visual cues: Is there a role in obesity? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2014, 74, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibehenne, B.; Todd, P.M.; Wansink, B. Dining in the dark. The importance of visual cues for food consumption and satiety. Appetite 2010, 55, 710–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, J. Visual influence on in-store buying decisions: An eye-track experiment on the visual influence of packaging design. J. Mark. Manag. 2007, 23, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, J.; Kristensen, T.; Grønhaug, K. Understanding consumers’ in-store visual perception: The influence of package design features on visual attention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, R.; Wedel, M. Attention capture and transfer in advertising: Brand, pictorial, and text-size effects. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mormann, M.; Fehr, E.; Hare, T.A. The impact of visual attention on value computation in goal-directed choice. Front. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 146. [Google Scholar]

- Van Loo, E.J.; Caputo, V.; Nayga, R.M.; Meullenet, J.F.; Ricke, S.C. Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic chicken breast: Evidence from choice experiment using eye tracking. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 41, 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- CONEP—Conselho Nacional de Saúde. Resolução nº 510. 2016. Available online: http://conselho.saude.gov.br/resolucoes/2016/Reso510.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Kytö, E.; Järveläinen, A.; Mustonen, S. Hedonic and emotional responses after blind tasting are poor predictors of purchase behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 70, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murias, M.; Major, S.; Davlantis, K.; Franz, L.; Harris, A.; Rardin, B.; Sabatos-DeVito, M.; Dawson, G. Validation of eye-tracking measures of social attention as a potential biomarker for autism clinical trials. Autism Res. 2018, 11, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J.H.; Watson, M.W. Regressão com uma variável dependente binária. In Econometria; Addison Wesley: São Paulo, Brasil, 2004; pp. 202–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J. Limited Dependent Variable Models and Sample Selection Corrections. In Introdutory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 5th ed.; South-Western; Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2013; pp. 604–609. [Google Scholar]

- Hair-Junior, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Analise Multivariada de Dados; Bookman: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2009; 688p. [Google Scholar]

- Pino, F. Modelos de decisão binários: Uma revisão. Rev. Econ. Agric. 2007, 54, 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kubberød, E.; Ueland, Ø.; Rødbotten, M.; Westad, F.; Risvik, E. Gender specific preferences and attitudes towards meat. Food Qual. Prefer. 2002, 13, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottin, C.; Eiras, C.E.; Chefer, D.M.; Barcelos, V.D.C.; Ramos, T.R.; Prado, I.N.D. Influencing factors of consumer willingness to buy cattle meat: An analysis of survey data from three Brazilian cities. Acta Sci. Anim. Sci. 2019, 41, e43871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Han, J.; Liang, R.; Dong, P.; Zhu, L.; Hopkins, D.L.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, X. Investigation of muscle-specific beef colour stability at different ultimate pHs. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 33, 1999–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Xu, B.; Hopkins, D.L.; Liang, R. Influence of oxygen concentration on the fresh and internal cooked colour of modified atmosphere packaged dark-cutting beef stored under chilled and superchilled conditions. Meat Sci. 2022, 188, 108773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, W.A.; Van Zyl, J.H.; Beeldersc, T.R. Eye-tracking consumers’ awareness of beef brands. Agrekon 2020, 59, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, D.J.; Orquin, J.L.; Visschers, V.H.M. Eye tracking and nutrition label use: A review of the literature and recommendations for label enhancement. Food Policy 2012, 37, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassu, R.T.; Uttaro, B.; Aalhus, J.L.; Zawadski, S.; Juárez, M.; Dugan, M.E.R. Type of packaging affects the colour stability of vitamin E enriched beef. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1868–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, A.C.; Contreras-Castillo, C.J.; Faria, J.A.F.; Gallo, C.R.; Silva, T.Z.; Shirahigue, L.D. Microbiological, colour and sensory properties of fresh beef steaks in low carbon monoxide concentration. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2010, 23, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, C.; Michel, C.; Youssef, J.; Gamez, X.; Cheok, A.D.; Spence, C. Colour–taste correspondences: Designing food experiences to meet expectations or to surprise. Int. J. Food Des. 2016, 1, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavieri, S.; Williams, K. Effects of packaging systems and fat concentrations on microbiology, sensory and physical properties of ground beef stored at 4 ± 1 °C for 25 days. Meat Sci. 2014, 97, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialkova, S.; Sasse, L.; Fenko, A. The role of nutrition labels and advertising claims in altering consumers’ evaluation and choice. Appetite 2016, 96, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, J.B.S.; Felício, P.E. Production systems—An example from Brazil. Meat Sci. 2010, 84, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardeshiri, A.; Rose, M.J. How Australian consumers value intrinsic and extrinsic attributes of beef products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 65, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressan, M.C.; Rodrigues, E.C.; Rossato, L.V.; Ramos, E.M.; Gama, L.T. Physicochemical properties of meat from Bos taurus and Bos indicus. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2011, 40, 1250–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shackelford, S.D.; Koohmaraie, M.; Miller, M.F.; Crouse, J.D.; Reagan, J.O. An evaluation of tenderness of the longissimus muscle of Angus by Hereford versus Brahman crossbred heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 1991, 69, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, T.L.; Cundiff, L.V.; Koch, R.M. Effect of marbling degree on beef palatability in Bos taurus and Bos indicus cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 1994, 72, 3145–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banović, M.; Fontes, A.; Barreira, M.M.; Grunert, K.G. Impact of product familiarity on beef quality perception. Agribusiness 2012, 28, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, R.; Visschers, V.; Siegrist, M. The role of health-related, motivational and sociodemographic aspects in predicting food label use: A comprehensive study. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Will, J.M.; Fernández-Celemín, L. Nutrition knowledge and use and understanding of nutrition information on food labels among consumers in the UK. Appetite 2010, 55, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Information | Description | % | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of weekly consumption | Once a week | 13% | 3 |

| 2 or 3 times a week | 61% | 14 | |

| 4 or 7 times a week | 26% | 6 | |

| Frequency of month purchase | Once a month | 9% | 2 |

| 2 or 3 times a month | 52% | 12 | |

| 4 or 5 times a month | 22% | 5 | |

| 6 or more times a month | 17% | 4 | |

| Gender | Male | 57% | 13 |

| Female | 43% | 10 | |

| Age range (years) | 18–30 | 74% | 17 |

| 31–40 | 26% | 6 | |

| Education | High School completed | 13% | 3 |

| University completed | 57% | 13 | |

| Postgraduate | 30% | 7 | |

| Average income (month) | USD 200.00–600.00 | 61% | 14 |

| USD 601.00–1000.00 | 26% | 6 | |

| USD 1001.00–3000.00 | 13% | 3 | |

| Location | São Paulo | 96% | 22 |

| Others | 4% | 1 |

| Variables | Coefficients | Standard Deviation | p-Value | MgE # |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercepto | 17.359 | 4.2607 | 0.0000 *** | - |

| FRESH.PRICE | 0.0952 | 0.0370 | 0.0101 ** | 0.0318 |

| CBROWNCO | −3.4719 | 1.1442 | 0.0024 *** | −0.1116 |

| FRESH.FBRIGHTCO | −0.5713 | 0.2405 | 0.0175 ** | −0.0050 |

| FRESH.FBROWNCO | −0.7133 | 0.3780 | 0.0592 * | −0.0062 |

| FRESH.TDARKCO | 3.7014 | 1.9604 | 0.0590 * | 0.0325 |

| FRESH.TNELLOREB | −3.3003 | 1.6080 | 0.0401 ** | −0.0289 |

| FRESH.TWITHOUTB | 13.2524 | 4.4611 | 0.0029 *** | 0.1163 |

| FRESH.TBROWNCO | −2.8524 | 1.3094 | 0.0293 ** | −0.0250 |

| FRESH.VDARKCO | −1.7553 | 0.6874 | 0.0106 ** | −0.0154 |

| FRESH.VSMALLMAR | −2.4407 | 0.7195 | 0.0007 *** | −0.0214 |

| FRESH.VMODERATEMAR | −0.9295 | 0.41418 | 0.0248 ** | −0.0081 |

| FRESH.VABUNDANTMAR | −1.6202 | 0.4790 | 0.0007 *** | −0.0142 |

| FRESH.VPRICE380 | −1.1141 | 0.5596 | 0.0465 ** | −0.0097 |

| FRESH.VWITHOUTB | −5.4550 | 1.5222 | 0.0004 *** | −0.0479 |

| FRESHQCONS_C | 5.3391 | 2.0705 | 0.0099 *** | 0.0265 |

| FRESHQPURCHASE_D | −7.3969 | 2.0462 | 0.0004 *** | −0.7977 |

| MED_COMP | −1.4765 | 0.5006 | 0.0031 *** | −0.0129 |

| n | 229 | |||

| AIC | 92.213 | |||

| Mc Fadden (Pseudo-R2) | 0.74 | |||

| Cox–Snell (Pseudo-R2) | 0.51 | |||

| NagelKerke (Pseudo-R2) | 0.83 |

| Variables | Coefficients | Standard Deviation | p-Value | MgE # |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercepto | 1.14007 | 1.62154 | 0.4820 ND | - |

| COOK.PRICE | 0.16837 | 0.06606 | 0.0108 ** | 0.0050 |

| COO.TOUGHMC | −2.21684 | 0.86441 | 0.0103 ** | −0.1660 |

| COO.FTOUGH | −0.88719 | 0.20065 | 0.0000 *** | −0.0266 |

| COO.FWEAKFLAVOUR | −0.36660 | 0.15630 | 0.0190 ** | −0.0110 |

| COO.VPRICE580 | −0.99133 | 0.32722 | 0.0024 *** | −0.0297 |

| COO.VPRICE900 | −2.28778 | 0.65485 | 0.0005 *** | −0.0686 |

| COO.VINTENSEFLAVOUR | −0.61987 | 0.29383 | 0.03489 ** | −0.0186 |

| COO.FREQCONSU_B | 2.09243 | 0.84142 | 0.0128 ** | 0.0867 |

| COO.FREQPURCHASE_D | −1.74068 | 0.87018 | 0.0454 ** | −0.0944 |

| N | 226 | |||

| AIC | 85.109 | |||

| Mc Fadden (Pseudo-R2) | 0.68 | |||

| Cox–Snell (Pseudo-R2) | 0.46 | |||

| NagelKerke (Pseudo-R2) | 0.77 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malheiros, B.A.; Spers, E.E.; Contreras Castillo, C.J.; Aroeira, C.N.; de Lima, L.M. The Role of Visual Attention and Quality Cues in Consumer Purchase Decisions for Fresh and Cooked Beef: An Eye-Tracking Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7360. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15137360

Malheiros BA, Spers EE, Contreras Castillo CJ, Aroeira CN, de Lima LM. The Role of Visual Attention and Quality Cues in Consumer Purchase Decisions for Fresh and Cooked Beef: An Eye-Tracking Study. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(13):7360. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15137360

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalheiros, Bruna Alves, Eduardo Eugênio Spers, Carmen Josefina Contreras Castillo, Carolina Naves Aroeira, and Lilian Maluf de Lima. 2025. "The Role of Visual Attention and Quality Cues in Consumer Purchase Decisions for Fresh and Cooked Beef: An Eye-Tracking Study" Applied Sciences 15, no. 13: 7360. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15137360

APA StyleMalheiros, B. A., Spers, E. E., Contreras Castillo, C. J., Aroeira, C. N., & de Lima, L. M. (2025). The Role of Visual Attention and Quality Cues in Consumer Purchase Decisions for Fresh and Cooked Beef: An Eye-Tracking Study. Applied Sciences, 15(13), 7360. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15137360