Abstract

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a condition characterized by difficulties with social interaction and communication. Studies show that people with ASD tend to enjoy using technology, as it provides them with a safe and trustworthy environment. Evaluating User eXperience (UX) in people with disabilities has been a challenge that studies have addressed in recent times. Several studies have evaluated the usability and UX of systems designed for people with ASD using evaluation methods focused on end users without disabilities. In reviewing studies that evaluate systems designed for people with ASD, considering the characteristics of these users, we discovered a lack of particularized UX models. We present a proposal of nine UX factors for people with ASD based on two approaches: (1) the characteristics, affinities, and needs of people with ASD, and (2) design guidelines and/or recommendations provided in studies on technological systems for people with ASD and/or interventions with these users. The nine UX factors for people with ASD provide a theoretical basis from which to adapt and/or create UX evaluation instruments and methods and to generate recommendations and/or design guidelines that are adequate for this context.

1. Introduction

The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [1] defines Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) as a developmental disorder that affects people’s communication and behavior. Additionally, it is established that ASD is a condition characterized by deficits in two core domains: (1) social communication and social interaction and (2) restricted repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, and activities.

Several studies have developed and evaluated User eXperience (UX) in systems for people with ASD. These studies have focused on evaluating UX using various methods available in the literature such as focus groups, eye tracking, heuristics evaluation, and questionnaires after interactions with the systems, which do not present sufficient details for evaluations. There is a lack of empirical evidence in their research, as described by a previous systematic literature review [2].

In a second literature review [3], we found studies that propose different characteristics to consider when working with people with ASD as well as others that propose guidelines and/or recommendations for designing systems for these users. However, no study presents particular UX factors for people with ASD. We think that it is important to consider a set of specific UX factors that could facilitate UX evaluation and design.

This is why, taking into account the works previously found in the literature [2,3] as well as new studies added for this research, we have designed a proposal of nine UX factors for people with ASD based on two approaches: (1) the characteristics, affinities, and needs of people with ASD, and (2) design guidelines and/or recommendations provided by studies focused on technological systems for people with ASD and/or interventions with these users. The nine proposed UX factors are focused on evaluating systems designed for adults with ASD of severity level 1, “Requiring support”, as defined by the DSM-5 [1].

This document is organized as follows: Section 2 presents a theoretical background; Section 3 describes relevant related work; Section 4 introduces and describes the process used to create a preliminary proposal of UX factors for people with ASD; Section 5 presents the final set of nine UX factors for people with ASD; and Section 6 presents a discussion.

2. Theoretical Background

Below are brief descriptions of ASD, UX, and UX models, which are relevant for this investigation.

2.1. Autism Spectrum Disorder

ASD is defined in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [1] as a condition characterized by deficits in two core domains: (1) social communication and social interaction, and (2) restricted repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, and activities. Additionally, people with ASD may or may not present secondary symptoms such as intellectual disability (ID), low tolerance for frustration, no verbal language, motor difficulties, and others. Three severity categories for ASD have been established [1] depending on the degree of support that the person requires and range from level 1 “Requiring support” to level 3 “Requiring very substantial support.”

2.2. User Experience

Standard ISO 9241-210 [4] defines user experience as a “user’s perceptions and responses that result from the use and/or anticipated use of a system, product or service.” Additionally, the standard describes UX as “users’ perceptions and responses include the users’ emotions, beliefs, preferences, perceptions, comfort, behaviors, and accomplishments that occur before, during and after use.” A component of UX is usability, a concept defined by the ISO 9241-11 standard [5] as the “extent to which a system, product or service can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a specified context of use.”

2.3. UX Models

Multiple authors have defined UX and usability models focused on providing indicators to measure “satisfaction” in the interaction between the user and the system or product. Some examples include (1) Guidance on Usability from The International Standard on Ergonomics of Human System Interaction [5], which defines three aspects to consider: effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction; (2) Jacob Nielsen’s model [6], which describes five attributes to consider: learnability, efficiency, memorability, errors, and satisfaction; (3) Llúcia Masip et al.’s model [7], which describes eleven facets to consider: dependability, usability, playability, accessibility, plasticity, communicability, cross-cultural capacity, emotionality, desirability, usefulness, and findability; and (4) Peter Morville’s model [8], which presents seven factors that help users have a meaningful and valuable user experience: useful, usable, desirable, findable, credible, accessible, and valuable.

3. Related Work

In a previous study [2], we analyzed the impact that technology has on people with ASD. One of the research questions answered in this research was “Which user experience and accessibility elements/methods are considered when analyzing the impact of technology on people with autism spectrum disorder?”. We found a lack of empirical evidence and details from studies evaluating user experience and/or usability in systems designed for people with ASD.

After the systematic literature review carried out previously [2] and a review of the literature at present, we found studies that have evaluated the user experience and/or usability in systems designed for people with ASD. Some studies [9,10,11] mention having carried out focus groups, and other studies [9,12,13] propose the use of eye tracking. In ref. [10,11,14,15,16,17], the authors distribute questionnaires to users after having interacted with the systems, and in the same way, studies such as [18,19,20] evaluate the usability of systems through the use of the “System Usability Scale” (SUS) [21] or SUS-ASD [22].

Vallefuoco et al. [23] evaluated the usability of their software system based on Moreno Ger’s methodology [24], which facilitates usability tests for serious games. Furthermore, studies [25,26,27] claim to have evaluated the usability of their systems designed for people with ASD based on an analysis of observations, through the collection of comments, and/or with the help of experts in the domain of people with ASD. On the other hand, studies such as Naziatul et al. [28] propose evaluating the usability of systems for people with ASD through adaptations of the Nielsen heuristics [29]. Furthermore, studies such as [15,30,31,32,33] claim to have developed systems for people with ASD with a focus on accessibility given by the use of touch screens.

These studies do not present empirical evidence or details that formalize the process of evaluating the user experience with systems designed for people with ASD. Additionally, no studies formally specify the attributes/factors/aspects of UX for systems designed for people with ASD, which we believe would provide a basis for formalizing the evaluation process. However, studies do identify the creation and/or use of design guidelines that characterize people with ASD as a means to develop systems for said people in different contexts, which can be a starting point for creating UX factors tailored to people with ASD. Below are studies that define design guidelines based on the characteristics of people with ASD.

3.1. Technology-Related Research

As described in [2], some studies have focused on proposing design guidelines for technological systems for people with ASD based on reviews of the literature and the characteristics of the users. Research has focused on creating/proposing design guidelines focused on tactile and nontactile systems for serious games and/or systems designed to develop learning skills in people with ASD.

In our previous study [3], a total of eleven studies focused on developing social skills were analyzed to propose design guidelines and best practices for future technological interventions in people with ASD. Here, a total of seven design guidelines are proposed: (1) structured and predictable learning environments; (2) generalization to daily life, (3) learning dynamics: individual and collaborative; (4) engagement through activity cycles and game elements; (5) error management; (6) mixed activities; and (7) no-touch and hybrid interfaces.

In ref. [34], a set of design guidelines for motion-based touchless interaction for medium-low functioning children with ASD are proposed. These design guidelines were developed based on empirical studies and collaborations with therapeutic centers. This set of design guidelines has been classified into two categories, the first of which is related to general aspects of interface/interaction and the second of which considers specific aspects according to the expected learning objectives, which in turn have been classified into the motor, cognitive, and social dimensions.

In ref. [35], the distances and sizes of pixels of the objects that systems for people with ASD use are established. The authors point out that 57 pixels is the minimum target size that touch systems must apply for users with ASD.

Studies such as those by Stavros Tsikinas and Stelios Xinogalos [36,37] and Stéphanie Carlier et al. [38] propose and/or compile design guidelines available in the literature on serious games for people with ASD. In ref. [36], a total of seven design guidelines for serious games for people with ASD are proposed based on existing design guidelines given in the literature: (1) feedback, (2) customization and personalization, (3) graphical interface, (4) game difficulty, (5) repetition, (6) motivators, and (7) participatory design. The authors in [37] compiled and created design guidelines for serious games that aim to improve life skills in young adults with ASD and intellectual disability (ID). After a review of the literature, the authors define a “game design framework” that focuses on three axes: (1) pedagogy, (2) learning content and game mechanics, and (3) evaluation. In the research by Carlier et al. [38], serious games were created to reduce stress and anxiety in parents and children with ASD, and for their creation, eleven design guidelines found in the literature and six design guidelines based on the experiences of specialized therapists were considered.

3.2. UX-Related Research

Studies have proposed the creation of design guidelines for focused systems for people with ASD considering aspects such as usability, accessibility, and task-centered user interface design (TCUID) based on reviews in the literature and the characteristics of said users.

In ref. [39], Chung and Ghinea discuss the use of technology to support the development of empathy in children with autism. Based on a review of the literature, a total of ten design guidelines are proposed and classified into four categories: graphical layout, navigation and structure, language, and interaction. The system was designed based on a human-centered design, and its acceptability and usability were evaluated through interviews, a survey of 12 sentences created based on the system usability scale (SUS) [21], defined design guidelines, and open-ended questions.

In a study by Khowaja and Salim [40], a total of 15 heuristics were defined based on Nielsen heuristics [29] and a compilation of 70 guidelines for the design and development of systems for children with ASD. These design guidelines were compiled after a review of the literature [41,42,43].

Hailpern et al. [44] described a real-time voice display system for people with ASD and speech delays (SPDs). The system was designed based on task-centered user interface design (TCUID), and after experiments and a review of the existing literature, a total of seven design guidelines were created. The proposed design guidelines are as follows: (1) minimize delay to interaction, (2) real-time is fun, (3) child customization, (4) dynamic computer correction, (5) robust microphone setup, (6) competence of the child, and (7) physical interaction.

Raymaker et al. [45] proposed a set of accessibility guidelines for websites used by people with ASD based on a website aimed at improving access to health care for autistic adults. The authors declare that they propose these accessibility guidelines based on the theory of accessibility and evaluate usability through evaluation surveys. A total of 20 accessibility guidelines are provided and are classified into three categories: physical accessibility, intellectual accessibility, and social accessibility.

In ref. [46], a systematic review of the literature is employed to define a set of recommendations for the development of software solutions adapted for people with ASD. The set of recommendations, called AutismGuide, includes a total of 69 recommendations categorized into 11 categories: (1) general usability principles, (2) nonfunctional requirements, (3) functional requirements, (4) adaptability, (5) guidance, (6) workload, (7) compatibility, (8) explicit control, (9) significance of codes, (10) error management, and (11) consistency.

Tan-MacNeilla et al. [47] evaluated whether parents of children with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD) perceived the Better Nights, Better Days (BNBD) intervention as usable, acceptable, and feasible. To evaluate these aspects, the authors created questionnaires for before and after the intervention, which were completed by the users. The questionnaires were developed based on Morville’s honeycomb model [8].

3.3. Nontechnological Intervention-Related Research

Studies have proposed different sets of design guidelines to be applied in places frequented by people with ASD. In Barakat et al. [48], a set of design guidelines is proposed to design a therapeutic garden for children with ASD with the objective of calming hyperreactive children and stimulating hyporeactive children with ASD. The design guidelines proposed by Barakat et al. [48] are classified under four categories: (1) visual principles as a therapeutic tool, (2) design elements as a therapeutic tool, (3) physical landscape features as a therapeutic tool, and (4) design guidelines, where the latter includes recommendations for security and safety and motor skills. McAllister and Maguire [49] proposed a total of 16 design guidelines for designing ASD-friendly classrooms. The 16 design guidelines specify the features of school environments that users interact with should include.

Although this research focuses on proposing UX factors to be used in technologies used by people with ASD, we believe that concepts such as promoting secure and safe environments and providing a transitional buffer before entering a classroom, among other characteristics, are necessary in any context that people with ASD interact with.

4. A Two-Step Preliminary Proposal of UX Factors for ASD

Given the need to formalize the user experience evaluation process in systems focused on people with ASD, a methodical process was carried out to make a preliminary proposal of user experience factors for people with ASD that consider their characteristics, difficulties, and/or affinities, as found in the literature. The preliminary proposal of user experience factors was created following two steps, which are detailed below.

4.1. Step 1: Adapting Morville UX Factors Based on ASD Characteristics

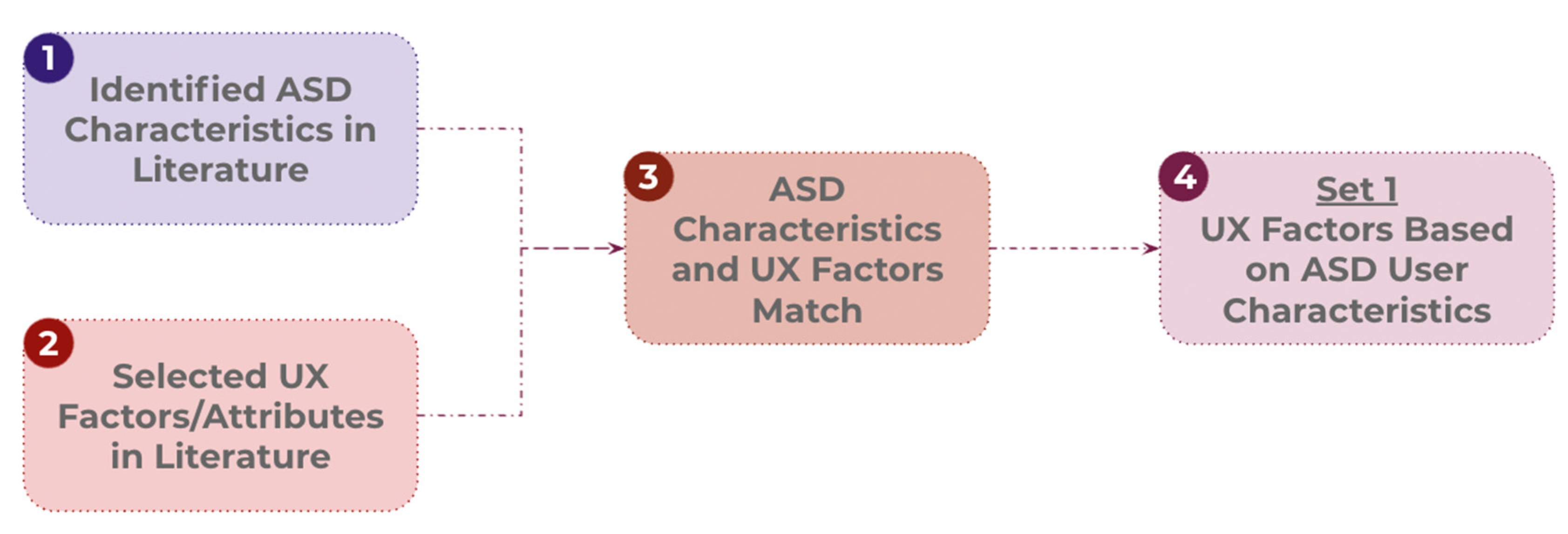

As shown in Figure 1, a preliminary proposal of specific UX factors for people with ASD is defined based on (i) a search of the literature of the characteristics, difficulties, and/or affinities of people with ASD, and (ii) the collection and selection of UX factors/attributes.

Figure 1.

Process for Defining UX Factors Based on ASD User Characteristics.

To perform this specification, we followed a four-step process to define specific UX factors for people with ASD: (1) the collection and grouping of characteristics, difficulties, and affinities in people with ASD; (2) the collection and selection of UX factors/attributes found in the literature; (3) matching identified characteristics and UX factors; and (4) the proposal of UX factors for people with ASD. Each step is detailed below.

4.1.1. Collection and Grouping of Characteristics/Difficulties/Affinities for People with ASD

In this step, we compiled and grouped the characteristics, difficulties, and affinities of people with ASD found in previous work [2,3] and information provided by the book Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [1]. Following this process, we compiled a set of 18 characteristics, difficulties, and affinities, which are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

ASD Characteristics from the Literature.

4.1.2. Collection and Selection of UX Factors

Authors have defined factors/attributes with the end goal of evaluating the usability and user experience of a specific product. Some examples of this include the following:

- Usability:

- ○

- Aspects [5]: effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction.

- ○

- Attributes [6]: learnability, efficiency, memorability, errors, and satisfaction.

- User experience:

- ○

- Facets [7]: dependability, usability, playability, accessibility, plasticity, communicability, cross-cultural capacity, emotionality, desirableness, usefulness, and findability.

- ○

- Factors [8]: useful, usable, desirable, findable, credible, accessible, and valuable.

The selection of such factors/attributes should be dependent on the nature and characteristics of the product and scope of the investigation. Considering the focus of this investigation, we selected the seven UX factors proposed by Morville [8], who states that the Useful, Usable, Desirable, Findable, Accessible, Credible, and Valuable factors contribute to a successful user experience. The definitions for each of these factors are presented in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Morville UX Factors.

4.1.3. Match between Identified Characteristics and UX Factors

After the compilation of the information described above, matching was employed. We matched the characteristics, difficulties, and affinities of people with ASD to the seven factors raised by Morville [8] to use these elements to specifically define what the user experience means for people with ASD.

To carry out the matching procedure, we performed the following steps: (i) for each of the seven UX factors, one or more characteristics, difficulties, and/or affinities of the users were associated, and (ii) a new specified UX factor was drafted to make it more specific to the selected characteristics. Table 3 presents an example of this mapping procedure, where we present characteristics that match the definition for Morville’s “findable” factor, and then we define an adapted UX factor for people with ASD. Appendix A Table A1 presents the matching results for all seven of Morville’s UX factors.

Table 3.

Sample of UX Factors Specified for ASD.

4.1.4. Preliminary Proposal of UX Factors for People with ASD Based on Characteristics

After collecting, analyzing, and refining the information described in the above sections, eight specific UX factors for systems used by people with ASD are proposed. Table 4 presents a preliminary definition for each of the factors.

Table 4.

Set 1: Preliminary Definitions of UX Factors Based on ASD User Characteristics.

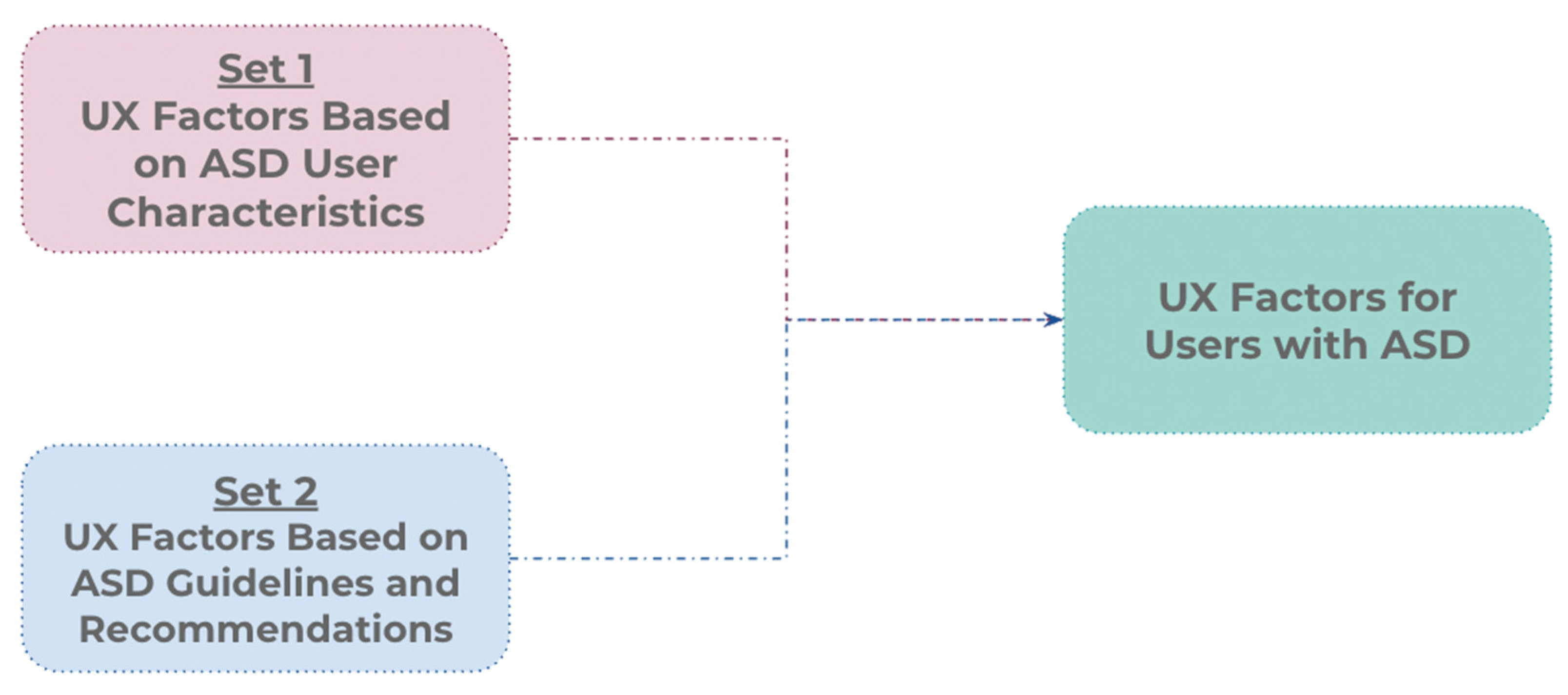

4.2. Step 2: Guidelines from the Literature

In a second step, as shown in Figure 2, after a review of the literature, we identified and compiled design guidelines and/or recommendations defined by authors based on the characteristics of people with ASD in technological and nontechnological contexts.

Figure 2.

Process for Defining UX Factors Based on ASD Guidelines and Recommendations.

We followed a three-step process to define UX factors for people with ASD based on ASD guidelines and recommendations: (1) the compilation of articles that propose and/or use design guides and/or recommendations, (2) grouping and categorizing design guidelines and/or recommendations based on their similarities, and (3) the proposal of a second set of UX factors for people with ASD.

4.2.1. Identifying Guidelines in the Literature

After a recent literature review, a total of 16 articles were found to focus on proposing and/or using guidelines to design systems or places frequented by people with ASD. From these articles, 290 design guidelines or recommendations were identified and are presented in Table A2 under the names or identifiers given by the authors. For studies [42,43], only the number of guidelines is shown since the authors do not provide short identifiers for them.

The studies present varying amounts of design guidelines and/or recommendations, which are generally focused on different aspects to consider when designing systems or interventions for people with ASD. These differences between quantities and categories may be attributable to this being a little explored field, and there is no consensus or established definition of aspects to consider when working with people with ASD, which supports the need to specify and agree on these aspects.

4.2.2. Grouping and Categorization

Following the results given in Table A2, the 290 design guidelines or recommendations found were grouped and categorized according to similarities in their definitions. In Table A3, the design guidelines or recommendations are categorized into 10 categories, which are divided into 32 subcategories of aspects to be consider when designing systems for people with ASD. For each of the subcategories, we cite a representative phrase for the group as an example selected from a study that considers this guideline or recommendation. An example of the grouping and categorization of guidelines and recommendations is given in Table 5. The full process employed is documented in Table A3.

Table 5.

ASD Guideline and Recommendation Categorization.

As shown in Table A3, multiple studies establish design guidelines and/or recommendations for aspects to consider when designing systems for people with ASD. Aspects such as personalization, customization, and graphics are most frequently considered in design guidelines and/or recommendations proposed in studies given the diverse characteristics and affinities that users may have. In contrast, aspects such as a simple and concise memory load, control, and recovery are the least explored by research.

4.2.3. Preliminary Proposal of UX Factors for People with ASD Based on Design Guidelines

Considering the grouping of similar concepts described in Table A3, a second set of refined preliminary UX factors for people with ASD based on design guidelines and/or recommendations is established. This refined proposal considers a total of eight UX factors, establishing an identifying name and specific definition, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Set 2: Preliminary Proposal of UX Factors Based on ASD Guidelines and Recommendations.

As the objective of our research is to establish UX factors that allow us to evaluate software systems designed for people with ASD, we eliminate the category “External Agents” presented in Table A3 because it focuses on aspects external to software.

5. A Set of UX Factors for People with ASD

Given the definitions established in set 1 (Table 4) and set 2 (Table 6), the preliminary UX factors were merged to formulate a proposal of UX factors for people with ASD, as shown in Figure 3. In this proposal, a total of nine UX factors are defined: Engaging, Predictable, Structured, Interactive, Generalizable, Customizable, Sense-aware, Attention retaining, and Frustration Free. Definitions for each of the proposed UX factors are presented in Table 7.

Figure 3.

Process of Defining Final UX Factors for Users with ASD.

Table 7.

UX Factors for Users with ASD.

In this set of UX factors, concepts such as “Engaging” or “Interactive” are included, which can be applied in contexts where learning is the focus of research. We believe that each of the proposed factors contributes to evaluating systems designed for people with ASD in general contexts and is not limited to learning settings. The nine UX factors established for people with ASD can be used to identify the most important or interesting areas that can be developed or addressed when designing systems for people with ASD. Defining these factors helps elucidate what UX implies and means and what is essential for ASD users. Additionally, we believe that these nine UX factors can contribute to adapting or creating new UX evaluation instruments and/or methods, which could contribute to the improvement of UX for systems designed for people with ASD.

6. Conclusions

Several studies have evaluated the UX and/or usability of systems for people with ASD. However, as evidenced in previous studies [2] and given the present investigation, empirical evidence and sufficient details are not presented to help us evaluate UX in systems for people with ASD. Additionally, it should be noted that no research has discussed UX factors of systems for people with ASD. Given the characteristics, affinities, and needs of people with ASD, we believe that it is pertinent to explore and specify UX factors that help evaluate systems designed for these users.

Given that there is no consensus on how to design specific UX factors regardless of the contexts in question, we used two means of search and information capture to establish guidance on UX factors for people with ASD.

The first approach focused on compiling the characteristics, affinities, and needs of people with ASD found in the literature as well as existing UX models. Since the UX models found do not consider the characteristics of people with ASD, we considered Morville’s honeycomb [8] model, and we tailored it to the characteristics, affinities, and needs of people with ASD. In this way, a first set of UX factors for use in systems designed for people with ASD was established.

The second approach involved compiling design guidelines and/or recommendations from the literature focused on technological systems for people with ASD. The design guidelines and/or recommendations found were grouped and classified to establish a new set of UX factors specific to systems designed for people with ASD.

We believe that these two approaches helped us analyze different perspectives on how the creation of specific UX factors should be carried out. An established UX factor creation methodology would have helped further support our research. We believe that the methods adopted helped us establish a good proposal on specific UX factors for systems designed for people with ASD.

In combining our preliminary UX factor proposals, we define a final set of UX factors for people with ASD that includes nine UX factors: Engaging, Predictable, Structured, Interactive, Generalizable, Customizable, Sense-aware, Attention Retaining, and Frustration Free.

These nine UX factors lead to a new UX model for people with ASD. The UX factors can be used to design appropriate systems for users with ASD. We believe that this set of UX factors will provide a theoretical basis for the possible adaptation or creation of evaluation instruments, methods, and methodologies and for the development of recommendations and design guidelines. These factors will help complete and enable future research that seeks to evaluate systems for people with ASD.

We believe that each of the established UX factors complements the others and that systems designed for people with ASD that comply with these factors will provide added value and will increase the satisfaction of users who interact with this system.

In future work, we intend to propose a methodology for evaluating the UX of people with ASD that uses adapted evaluation instruments and methods for users with ASD based on the new nine-factor UX model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.V., C.R. and F.B.; methodology, K.V., C.R. and F.B.; validation, K.V. and C.R.; formal analysis, K.V. and C.R.; investigation, K.V., C.R. and F.B.; data curation, K.V.; writing—original draft preparation, K.V.; writing—review and editing, K.V., C.R. and F.B.; visualization, K.V.; supervision, C.R. and F.B.; project administration, K.V. and C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Katherine Valencia is a beneficiary of ANID-PFCHA/Doctorado Nacional/2019-21191170.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

UX Factors Specified for ASD.

Table A1.

UX Factors Specified for ASD.

| Morville UX Factor | Characteristics/Difficulties/Affinities for People with ASD | UX Factors for People with ASD |

|---|---|---|

| Useful |

|

|

| Usable |

|

|

| Desirable |

|

|

| Findable |

|

|

| Accessible |

|

|

| Credible |

|

|

| Valuable |

|

|

Table A2.

ASD Guidelines and Recommendations Provided in the Literature.

Table A2.

ASD Guidelines and Recommendations Provided in the Literature.

| Title | Guidelines |

|---|---|

| Design Guidelines for Serious Games Targeted to People with Autism [36]. | Feedback |

| Customization and personalization | |

| Graphical interface | |

| Increasing game difficulty | |

| Repetition | |

| Motivators | |

| Participatory design | |

| Nature as a Healer for Autistic Children [48]. | Visual principle as a therapeutic tool |

| Design elements as a therapeutic tool | |

| Physical landscape feature as a therapeutic tool | |

| Landscape resources and materials as a therapeutic tool | |

| Design guidelines | |

| Designing and Evaluating Touchless Playful Interaction for ASD Children [34]. | General guidelines |

| Goal-specific guidelines: Motor skills | |

| Goal-specific guidelines: Cognitive skills | |

| Goal-specific guidelines: Social skills | |

| Design Considerations for the Autism Spectrum Disorder-Friendly Key Stage 1 Classroom [49]. | Threshold and entrance |

| Cloakroom provision | |

| Sight lines entering the classroom | |

| Visual timetable | |

| High-level glazing | |

| Volumetric expression | |

| Control | |

| Access to classroom external play | |

| Access to school playground | |

| Quiet room | |

| Toilet provision | |

| Kitchen | |

| Floor area | |

| Storage | |

| Computer provision | |

| Workstations | |

| Designing Visualizations to Facilitate Multisyllabic Speech with Children with Autism and Speech Delays [44]. | Minimize delay to interaction |

| Real-time is fun | |

| Child customization | |

| Dynamic computer correction | |

| Robust microphone setup | |

| Competence of the child | |

| Physical interaction | |

| Assessing the Target’ Size and Drag Distance in Mobile Applications for Users with Autism [35]. | Minimum pixel size |

| Empowering Children with ASD and Their Parents: Design of a Serious Game for Anxiety and Stress Reduction [38]. | Customizability |

| Evolving tasks | |

| Unique goal | |

| Instructions | |

| Reward | |

| Repeatability | |

| Transitions | |

| Minimalistic graphics | |

| Clear audio | |

| Dynamic stimuli | |

| Serendipity | |

| Sound and music | |

| Background story | |

| Language and text | |

| Actions and goals | |

| Simplicity | |

| Scoring | |

| Towards a Serious Games Design Framework for People with Intellectual Disability or Autism Spectrum Disorder [37]. | Pedagogy |

| Learning content and game mechanics | |

| Evaluation | |

| Development of the AASPIRE Web Accessibility Guidelines for Autistic Web Users [45]. | Physical accessibility |

| Intellectual accessibility | |

| Social accessibility | |

| AutismGuide: Usability Guidelines to Design Software Solutions for Users with Autism Spectrum Disorder [46]. | General usability principles |

| Nonfunctional requirements | |

| Functional requirements for caregivers/partners | |

| Adaptability | |

| Guidance | |

| Workload | |

| Compatibility | |

| Explicit control | |

| Significance of codes | |

| Error management | |

| Consistency | |

| Towards Developing Digital Interventions Supporting Empathic Ability for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder [39]. | Graphical layout |

| Navigation and structure | |

| Language | |

| Interaction | |

| Creating Individualized Computer-Assisted Instruction for Students with Autism Using Multimedia Authoring Software [41]. | Learning styles of individual students |

| Independent responding | |

| Social interaction | |

| Responsivity | |

| Age appropriateness | |

| Overlearning | |

| Natural environment | |

| Generalization | |

| Communication attempts | |

| Student choice of stimulus materials | |

| Cognitive ability | |

| Task variation | |

| Over-selectivity | |

| Vary the reinforcers | |

| Multiple cues | |

| Prompts | |

| Maximal use of technology | |

| Data collection as a design feature | |

| Learning Styles of Autistic Children [43]. | The authors do not detail specific categories for 18 guidelines and/or recommendations |

| Understanding Natural Language [42]. | The authors do not detail specific categories for eight guidelines and/or recommendations |

| Heuristics to Evaluate Interactive Systems for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) [40]. | Visibility of system status |

| Match between system and the real world | |

| Consistency and standards | |

| Recognition rather than recall | |

| Aesthetic and minimalist design—minimize distraction and keep design simple | |

| User control and freedom | |

| Error prevention | |

| Flexibility and efficiency of use | |

| Help users recognize, diagnose, and recover from errors | |

| Help and documentation | |

| Personalization of screen items | |

| User interface screens of the system | |

| Responsiveness of the system | |

| Track user activities, monitor performance, and repeat activity | |

| Use of multimodalities for communication | |

| Technology-Based Social Skills Learning for People with Autism Spectrum Disorder [3]. | Structured and predictable learning environment |

| Generalization to daily life | |

| Learning dynamics: individual and collaborative | |

| Engagement through activity cycles and game elements | |

| Error managing | |

| Mixed activities | |

| No-touch and hybrid interfaces |

Table A3.

ASD Guideline and Recommendation Categorization.

Table A3.

ASD Guideline and Recommendation Categorization.

| Category | Subcategory | Definition | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement | Feedback | “Software solution designed for users with ASD must (…) provide immediate feedback on the user’s actions (the response time must be as short as possible).” [46] | [3,36,40,43,46,48] |

| Rewards | “Offering a reward after a good performance, increases the child’s motivation, engagement and implicitly improves skills.” [38] | [3,34,38] | |

| Motivation | “Motivation encourages users to achieve objectives and develop expected behaviors. This motivation can be extrinsic and intrinsic.” [3] | [3,34,36,37,41] | |

| Task Interaction | Task Design | “Software solutions designed for users with ASD must take account of their various characteristics (habits, skills, age, expectations, etc.) and adapt the tasks, navigation, layout, etc., accordingly.” [46] | [34,38,41,43,46] |

| Evolution | “Increasing levels of motor or cognitive complexity should be incorporated in the game.” [38] | [3,34,36,37,38,44] | |

| Simple and Concise | “Make content as concise as possible without sacrificing precision and specificity, to reduce cognitive burden.” [45] | [45] | |

| Instructions | “The software should speak directions to the student in a clear and direct manner.” [41] | [34,38,39,40,41,45,46] | |

| Memory Load | “Minimise the user’s memory load by making objects, actions, and options visible. The user should not have to remember information from one part of the screen to another. Instructions for use of the system should be visible or easily retrievable whenever appropriate.” [40] | [40] | |

| Goal | “There should be one unique explicit goal to reach within a gaming session.” [38] | [34,37,38] | |

| Generalizable | Generalizable | “The system should speak the users’ language, with words, phrases and concepts familiar to the user, rather than system-oriented terms. Follow real-world conventions, making information appear in a natural and logical order.” [40] | [3,40,41,45] |

| Personalization and Customization | Personalization | “The system should allow personalisation of screen items based on needs, abilities and preferences of an individual child. Screen items should be large enough for children to read and interact with. It should also allow them to change various settings of system background, font, colour, screen size and others.” [40] | [34,36,37,38,40,44,45,46] |

| Customization | “Software solutions designed for users with ASD must react to the context and these users’ needs and preferences.” [46] | [3,34,38,40,41,43,44,45,46,48] | |

| Senses | Layout | “Use the simplest interface possible for ease of understanding.” [45] | [35,39,41,42,43,45,46,48,49] |

| Graphics | “Graphics should be aesthetically pleasing, but always functional. Irrelevant elements might form a distraction and can lead to loss of attention. Too many visual or colors might trigger anxiety as it might be difficult for the child to interpret individual elements.” [38] | [34,36,38,39,41,43,45,46,48] | |

| Language | “Any language and text present in the game should be free from figures of speech and as clear as possible” [38] | [38,39,43,45,46] | |

| Workload | “Software solutions designed for users with ASD must promote their perception, concentration, attention, memory, etc. They must therefore (…) avoid users being exposed to large numbers of functionalities, images, animations, etc., at any one time” [46] | [37,40,43,46,49] | |

| Audio | “Children with ASD can be sensitive to audio stimuli, which can create extra stress. Sound or music can be used to provide feedback on actions, to complement a visual reward or during a transition phase in the game.” [38] | [34,38,41,42,43,46] | |

| Physical | “Children want to touch everything. Touch is an easy-to-understand interaction. Therefore, design systems that not only respond to touch, but provide meaningful feedback for those interaction” [44] | [3,34,42,44,46,48] | |

| Structure, Repeatability, and Predictability | Structured | “Children with autism thrive in a structured environment. Establish a routine and keep it as consistent as possible.” [43] | [3,39,42,43,45] |

| Repetition | “Children with autism generally enjoy repetition and may engage in repetitive activity to the detriment of other activities.” [42] | [34,38,41,42,43,46,48] | |

| Consistency | “The system should use clear and consistent language so that users do not have to wonder whether different words, situations, or actions mean the same thing. Follow platform conventions in the design for consistency.” [40] | [34,38,39,40,43,45,46] | |

| Predictability | “When working with people with autism spectrum disorder, it must be ensured that we provide a structured and predictable learning environment, since people with ASD have restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, interests or verbal and non-verbal activities.” [3] | [3,34,38,39,42,43,46] | |

| Control | “Software solutions designed for users with ASD must ensure that they always have control (e.g., pause, restart) over the computer processing.” [46] | [42,43,46] | |

| Attention and Timing | Attention Retention | “Providing animations or music helps to retain the child’s attention. If there are no visual or auditive stimuli, the child might lose his/her attention. A prolonged static visual, on the other hand, might trigger unwanted behavior, such as stereotyped movements or motor rigidity, e.g., gazing at a static image on the screen.” [38] | [34,38,41,42,44] |

| Distraction | “The time of restarting a session or switching from one level to the next one must be minimized, to reduce the risk of a child’s loss of concentration during the transition.” [34] | [34,38,40,42,46] | |

| Timing | “When designing software for children, ensure that when the child wants to engage, and the software is ready to respond and delays are minimized.” [44] | [38,40,41,43,44] | |

| External Agents | Location | “Select a location with the least amount of distractions possible. high-pitched or humming noise, adjacent traffic and noise from air conditioning compressors can be overwhelming.” [48] | [34,48,49] |

| People | “It is important to include special education teachers and professionals in the design phase of a SG. They can define the requirements, goals and learning objectives of the game.” [37] | [36,37,41,46] | |

| Hardware | “Software solutions designed for users with ASD must … have a long lifespan (robust hardware, without frequent replacement need, etc.) and high availability (independent of Wi-Fi and available via Web, tablet and laptop)” [46] | [40,41,46] | |

| Error Management | Prevention | “Even better than good error messages is a careful design which prevents a problem from occurring in the first place. Either eliminate error-prone conditions or check for them and present users with a confirmation option before they commit to the action.” [40] | [3,40,42,45,46] |

| Recognition | “(…) provide good-quality error messages (clear, multimedia message: video, audio, animation) and avoid indicating success or failure solely by means of a colour or a facial expression (frown, smile, etc.)” [46] | [40,41,46] | |

| Recovery | “Users often choose system functions by mistake and will need a clearly marked ‘emergency exit’ to leave the unwanted state without having to go through an extended dialogue. Support undo and redo. The system should allow users to move from one part to another and provide the facility to repetitively perform activities.” [40] | [40,46] |

References

- American Psychatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, K.; Rusu, C.; Quiñones, D.; Jamet, E. The Impact of Technology on People with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Literature Review. Sensors 2019, 19, 4485. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, K.; Rusu, V.Z.; Jamet, E.; Zuñiga, C.; Garrido, E.; Rusu, C.; Quiñones, D. Technology-Based Social Skills Learning for People with Autism Spectrum Disorder. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Copenhagen, Denmark, 19–24 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. Ergonomics of Human System Interaction—Part 210: Human-Centered Design for Interactive Systems; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction—Part 11: Usability: Definitions and Concepts; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. NN/g Nielsen Norman Group. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-101-introduction-to-usability/ (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Masip, L.; Oliva, M.; Granollers, T. User Experience Specification through Quality Attributes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Lisbon, Portugal, 5–9 September 2011; pp. 656–660. [Google Scholar]

- Morville, P. Semantic Studios. Available online: http://semanticstudios.com/user_experience_design/ (accessed on 12 October 2019).

- Schmidt, M.; Beck, D. Computational Thinking and Social Skills in Virtuoso: An Immersive, Digital Game-Based Learning Environment for Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Immersive Learning Research Network iLRN., Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 27 June–1 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Santarosa, L.M.C.; Conforto, D. Educational and Digital Inclusion for Subjects with Autism Spectrum Disorders in 1:1 Technological Configuration. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 60, 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- Backman, A.; Mellblom, A.; Norman-Claesson, E.; Keith-Bodros, G.; Frostvittra, M.; Bölte, S.; Hirvikoski, T. Internet-Delivered Psychoeducation for Older Adolescents and Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (SCOPE): An Open Feasibility Study. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2018, 54, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Rios, P.C. Adaptable User Interfaces for People with Autism: A Transportation Example. In Proceedings of the 16th International Web for All Conference: Addressing Information Barriers, Lyon, France, 23–25 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, P.R.K.; Lahiri, U. Classification Approach for Understanding Implications of Emotions Using Eye-Gaze. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2020, 11, 2701–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, M.; Díaz, J.; Madela, J.; Mag-Usara, M.; Sabellano, D. Fill Me App: An Interactive Mobile Game Application for Children with Autism. Int.J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2016, 10, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, D.; Kholodovsky, M.; Arab, R.; Smith, D.S.; Asanov, P.; Gillespie-Lynch, K. Participatory Design of a Hybrid Kinect Game to Promote Collaboration between Autistic Players and Their Peers. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 706–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, V.; Coheur, L.; Sardinha, A. VITHEA-Kids: A Platform for Improving Language Skills of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. In Proceedings of the International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Lisbon, Portugal, 26–28 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kilmer, M. Primary Care of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Pilot Program Results. Nurse Pract. 2020, 45, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caria, S.; Paternò, F.; Santoro, C.; Semucci, V. The Design of Web Games for Helping Young High-Functioning Autistics in Learning How to Manage Money. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2018, 23, 1735–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.M.; Silva, D.P.D.; Theodório, D.P.; Silva, W.W.; Rodrigues, S.C.M.; Scardovelli, T.A.; Silva, A.P.; Bissaco, M.A.S. ALTRIRAS: A Computer Game for Training Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in the Recognition of Basic Emotions. Int. J. Comput. Games Technol. 2019, 2019, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleery, J.P.; Zitter, A.; Solorzano, R.; Turnacioglu, S.; Miller, J.S.; Ravindran, V.; Parish-Morris, J. Safety and Feasibility of an Immersive Virtual Reality Intervention Program for Teaching Police Interaction Skills to Adolescents and Adults with Autism. Autism Res. 2020, 13, 1418–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A “Quick Dirty” Usability Scale. In Usability Evaluation in Industry; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 1996; pp. 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Parish-Morris, J.; Solórzano, R.; Ravindran, V.; Sazawal, V.; Turnacioglu, S.; Zitter, A.; Miller, J.; McCleery, J. Immersive Virtual Reality to Improve Police Interaction Skills in Adolescents and Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Preliminary Results of a Feasibility and Safety Trial. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual CyberPsychology, CyberTherapy & Social Networking Conference, Gatineau, QC, Canada, 26–28 June 2018; pp. 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Vallefuoco, E.; Bravaccio, C.; Pepino, A. Serious Games in Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Example of Personalised Design. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education, Porto, Portugal, 21–23 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Ger, P.; Torrente, J.; Hsieh, Y.G.; Lester, W.T. Usability Testing for Serious Games: Making Informed Design Decisions with User Data. Adv. Hum. Comput. Int. 2012, 2012, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanouni, P.; Jarus, T.; Zwicker, J.G.; Lucyshyn, J. An Interactive Serious Game to Target Perspective Taking Skills among Children with ASD: A Usability Testing. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo-Ponsaran, N.M.; Lerner, M.D.; McKown, C.; Weber, R.J.; Karls, A.; Kang, E.; Sommer, S.L. Web-Based Assessment of Social-Emotional Skills in School-Aged Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism Res. 2019, 12, 1260–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laxmidas, K.; Avra, C.; Wilcoxen, C.; Wallace, M.; Spivey, R.; Ray, S.; Polsley, S.; Kohli, P.; Thompson, J.; Hammond, T. CommBo: Modernizing Augmentative and Alternative Communication. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2020, 145, 145. [Google Scholar]

- Naziatul, A.A.; Wan, W.A.; Ahmad, H. The Design of Mobile Numerical Application Development Lifecyle for Children with Autism. J. Teknol. 2016, 78, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J.; Molich, R. Heuristic Evaluation of User Interfaces. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing System, Seattle, WA, USA, 1–5 April 1990; pp. 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Tuğbagül Altan, N.; Göktürk, M. Providing Individual Knowledge from Students with Autism and Mild Mental Disability Using Computer Interface. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 17–21 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tashnim, A.; Nowshin, S.; Akter, F.; Das, A.K. Interactive Interface Design for Learning Numeracy and Calculation for Children with Autism. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Technology and Electrical Engineering ICITEE, Phuket, Thailand, 12–13 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hourcade, J.P.; Bullock-Rest, N.E.; Hansen, T.E. Multitouch Tablet Applications and Activities to Enhance the Social Skills of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2012, 16, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaruzaman, N.N.; Jomhari, N. Digital Game-Based Learning for Low Functioning Autism Children in Learning Al-Quran. In Proceedings of the Taibah University International Conference on Advances in Information Technology for the Holy Quran and Its Sciences NOORIC, Madinah, Saudi Arabia, 22–25 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli, L.; Garzotto, F.; Gelsomini, M.; Oliveto, L.; Valoriani, M. Designing and Evaluating Touchless Playful Interaction for ASD Children. In Proceedings of the 2014 conference on Interaction design and children, New York, NY, USA, 17–20 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Quezada, A.; Juarez-Ramirez, R.; Jimenez, S.; Ramirez-Noriega, A.; Inzunza, S.; Munoz, R. Assessing the Target’ Size and Drag Distance in Mobile Applications for Users with Autism. In Proceedings of the 6th World Conference on Information Systems and Technologies, Naples, Italy, 27–29 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tsikinas, S.; Xinogalos, S. Design Guidelines for Serious Games Targeted to People with Autism. In Proceedings of the 6th International KES Conference on Smart Education and e-Learning, St. Julian’s, Malta, 17–19 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tsikinas, S.; Xinogalos, S. Towards a Serious Games Design Framework for People with Intellectual Disability or Autism Spectrum Disorder. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 3405–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlier, S.; Paelt, S.V.; Ongenae, F.; Backere, F.D.; Turck, F.D. Empowering Children with ASD and Their Parents: Design of a Serious Game for Anxiety and Stress Reduction. Sensors 2020, 20, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chung, S.; Ghinea, G. Towards Developing Digital Interventions Supporting Empathic Ability for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Khowaja, K.; Salim, S. Heuristics to evaluate interactive systems for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132187. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, K.; Boone, R. Creating Individualized Computer-Assisted Instruction for Students with Autism Using Multimedia Authoring Software. Focus Autism Dev. Disabil. 1996, 11, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winograd, T. Understanding Natural Language. Cognit. Psychol. 1972, 3, 1–191. [Google Scholar]

- UKEssays. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20160913195408/http://www.ukessays.co.uk/essays/design/autism.php (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Hailpern, J.; Harris, A.; Botz, R.L.; Birman, B.; Karahalios, K. Designing Visualizations to Facilitate Multisyllabic Speech with Children with Autism and Speech Delays. In Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference, DIS ’12, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 11–15 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Raymaker, D.; Kapp, S.; McDonald, K.; Weiner, M.; Ashkenazy, E.; Nicolaidis, C. Development of the AASPIRE Web Accessibility Guidelines for Autistic Web Users. Autism Adulthood 2019, 1, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aguiar, Y.; Galy, E.; Godde, A.; Tremaud, M.; Tardif, C. AutismGuide: A Usability Guidelines to Design Software Solutions for Users with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan-MacNeill, K.; Smith, I.; Weiss, S.; Johnson, S.; Chorney, J.; Constantin, E.; Shea, S.; Hanlon-Dearman, A.; Brown, C.; Godbout, R.; et al. An EHealth Insomnia Intervention for Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Results of a Usability Study. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 98, 103573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakat, H.; Bakr, A.; El-Sayad, Z. Nature as a Healer for Autistic Children. Alex. Eng. J. 2019, 58, 353–366. [Google Scholar]

- Mcallister, K.; Maguire, B. Design Considerations for the Autism Spectrum Disorder-friendly Key Stage 1 Classroom. Support. Learn. 2012, 27, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopler, E.; Mesibov, G. Insider’s point of view. In High-Functioning Individuals with Autism; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Grynszpan, O.; Weiss, P.; Perez-Diaz, F.; Gal, E. Innovative Technology-Based Interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. Autism 2014, 18, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S. Social and Pragmatic Deficits in Autism: Cognitive or Affective? J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1988, 18, 379–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaziuddin, M.; Ghaziuddin, N.; Greden, J. Depression in Persons with Autism: Implications for Research and Clinical Care. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2002, 32, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jasmin, E.; Couture, M.; Mckinley, P.; Reid, G.S.; Fombonne, É.; Gisel, E. Sensori-Motor and Daily Living Skills of Preschool Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 39, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, L.; Ganz, J.; Davis, J.; Boles, M.; Hong, E.; Ninci, J.; Gilliland, W. Generalization and Maintenance of Functional Living Skills for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review and Meta-Analysis. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 3, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, S.; Porayska-Pomsta, K.; Smith, T. ECHOES: An Intelligent Serious Game for Fostering Social Communication in Children with Autism. Inf. Sci. 2014, 264, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyfer, T.; Folstein, S.; Bacalman, S.; Davis, N.; Dinh, E.; Morgan, J.; Tager-Flusberg, H.; Lainhart, J. Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders in Children with Autism: Interview Development and Rates of Disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2006, 36, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).