1. Introduction

Changes in land use, including the forest cover, are among the most distinct effects of human activity on the environment. A decrease of the intensity of agriculture along with an increase of forest areas can be observed throughout Europe; currently these are the most important land cover changes in this continent [

1,

2,

3]. One of the reasons behind a forest cover increase is the abandonment of land that was previously used for agricultural purposes. This is because the succession of climax communities—mixed forests in Central Europe—is a long-term effect of the cessation of the agricultural use of fields. An area subject to land abandonment is defined as “land used for agricultural purposes until recent times but not currently cultivated, with a noticeable cover of shrubs” [

4]. The process of land abandonment affects the entire area of the European Union (EU) and is the subject of special reports [

5,

6]. Based on the analysis of satellite data, Estel et al. [

7] estimated that 128.7 million ha were affected by land abandonment in Europe. Prishchepov et al. [

8], on the other hand, estimated that land abandonment affected ca. 14% of cultivated land in north-eastern Poland between 1990 and 2000.

Transformations in the land cover observed in Europe today are primarily a result of socio-economic changes. In Central Europe, including Poland, processes of land abandonment have intensified during the last 30 years, after the change of the social and economic system [

9,

10]. In the socialist era, farmers were obliged to cultivate land and a large part of the production was exported to the Soviet Union. In addition, population density in rural areas was higher, and multi-generational families lived on farms. Currently, due to the decreasing demand for land and the increased development of high-yield farming, intensive land use for agricultural purposes is concentrated in areas with favourable conditions for farming, while it has decreased in other areas. Land abandonment in Poland is mainly caused by a lower profitability of agricultural production, since much higher profits can be achieved in other areas of economic activity [

11,

12]. This is especially observed in areas where there are small family farms. This process became slightly less intensive after 2004 thanks to Poland’s accession to the European Union and direct area-based payments [

13].

The abandonment of land is a complex process of land use change, influenced by various natural and socio-economic factors [

8,

14]. Rey Benayas et al. [

15] indicated three main groups of factors influencing land abandonment: (a) ecological (land, relief, soil, erosion, and climate); (b) socio-economic (market, depopulation, technological progress, land ownership, and accessibility); (c) inadequacy of agricultural systems and poor land management. From the perspective of the rational use of natural resources, it is crucial to understand whether land abandonment affects exclusively areas that are the least favourable to agricultural production. So far, the problem of the impact of the natural environment on land use changes has been studied primarily with regard to changes in forest cover. Economic factors are usually identified as the main driving forces of this process [

16,

17]. Some researchers also emphasize the role of environmental components such as soil cover or land relief that may impact the spatial changes in forest cover [

18,

19,

20,

21]. The present study indicates that the abandoned fields in the Baltic states and Poland are mainly concentrated in regions with poor soils (peat or soils on morainic deposits) due to their high water content [

22].

Although there is extensive international literature on land abandonment, very few studies deal with the scope, stages, and factors determining the abandonment of land [

23]. It should be stressed that Poland is a peculiar example of a post-socialist country, where agriculture was not fully nationalised after the Second World War and private ownership dominated in the land ownership structure. In addition, land consolidation met with huge difficulties and resistance of the farmers. That is why the peculiar pattern of highly fragmented land has survived in most areas in south-eastern (SE) Poland. The present socio-economic structures in rural areas are very closely linked to the historical development factors and accessibility of urban markets, including, in particular, the labour market [

24].

After World War II, the conditions for land use in Poland changed completely, which resulted from the shifting of borders west to the Oder. It was primarily the “recovered lands” that became the basis for large-scale agriculture conducted by state-owned farms. In contrast, in central and south-eastern Poland, traditional agriculture has survived, which is often very fragmented and economically inefficient. Farmers sought additional (often main) income in employment in other sectors of the economy. The practice of farmers having two-professions ended with the economic crisis and political transformation of the late 1980s and early 1990s, when this group lost employment at first. The 1990s were very difficult for the Polish countryside. It was only the accession to the European Union and the gradual opening of the labour market that released the population potential; some people emigrated, and some went abroad to work. In those areas where the agricultural production potential is low, cultivation has ceased, even EU subsidies have not been able to fully prevent this. On the one hand, land remains a sentimental good, but on the other, it is a capital investment.

The strong fragmentation of land in SE Poland is a significant reason for land abandonment. The mean size of arable land in a farm holding is 7.86 ha in the Lublin Province, and 10.81 ha at the national scale. Land fragmentation, where an individual farmer has several small separate plots, increases the costs of farming. No land abandonment prevention policy has been developed in Poland. The management of agricultural land in the case of huge fragmentation of land ownership in the SE part of the country is very difficult. Most farmers in these areas do not participate in the economic development of the country because they produce primarily for their own needs and not for sale. Less than 10% of all farms produce for the market. The rest of the farmers make a living from paid employment and social benefits. In addition, Polish farmers are quite conservative, and changes are taking place very slowly. It is important for them to own the land but not necessarily to produce crops.

Difficulties in tillage operations are conducive to land abandonment because the impossibility of the mechanisation of agricultural production undermines the competitiveness of products in a free market economy. Therefore, steep slopes, small (narrow) plots, and areas with poor accessibility are no longer cultivated [

25]. In a free market economy, which in Poland has been the case since the end of the 20th century, there is no need to use all of the arable land because it is not economically viable. Therefore, many areas, though officially classified as arable land, are currently not used for crop production. Thus, relying on official statistical data does not ensure a full (and representative) picture of the intensity of this process. Land abandonment as a cessation of agricultural activity on the land without changing its status in the cadastre.

The traditional Polish rural areas are not attractive places to live and work. There is an outflow of young people (especially women), which leads to reduced population density, ageing of the rural population, and a disturbed balance between men and women. These unfavourable phenomena are characteristic of the so-called problem areas, usually in peripheral locations. A problem area is an area of a special phenomenon in the field of spatial management or a place where there is an occurrence of spatial conflicts. At the same time, non-agricultural functions become more important as a source of livelihood in some areas, while the role of agriculture decreases in the process of deagrarianization. Jobs are created outside of the agricultural sector as the multifunctionality of rural areas develops [

24]. The appropriate use of agricultural land as a natural resource is particularly significant in this respect. It is also important to prevent processes that are not advantageous from environmental and economical perspectives.

The study objective was to assess the intensity of land abandonment in SE Poland, using the example of the Lublin Province, and to identify the determinants of this process. The Lublin Province is an important area of agricultural production in Poland, while also being a peripheral region that is among the poorest in the European Union. At the same time, it is characterized by a varied mosaic of (narrow) parcels and crops. Research was conducted at two spatial scales. First, we analysed 20 rural districts, for which we assessed the correlation of the magnitude of land abandonment with the corresponding indicators of the socio-economic characteristics and a synthetic agricultural production space assessment index [

26]. We also analysed the impact of the level of detail of land cover data on the result of the assessment of land abandonment intensity under mosaic land-use conditions. Since small-scale data (e.g., CORINE Land Cover) are usually used in studies of this kind, we attempted to assess the intensity of the processes based on a detailed, expert analysis of detailed aerial photographs (scale 1:500). The studies were conducted in Susiec District (Tomaszów County), characterized by diversified environmental conditions and an intensive land use mosaic. In this case, particular attention was devoted to the natural factors of land abandonment, i.e., topography and soil quality.

2. Materials and Methods

Lublin Province lies in the south-east of Poland (

Figure 1). It covers nearly 25,000 km

2 and is inhabited by more than 2.1 million people. The population density, 84 people/km

2, is distinctly lower than the national average of 123 people/km

2. About 46% of the inhabitants live in cities. Fertile soils, Cambisols, Luvisols, and Chernozems (1st, 2nd, and 3rd complexes of agricultural suitability classes), occur in the central part of the province, while agricultural land covers 63% of its area. A high degree of farmland fragmentation, rare in present-day Europe, is a distinguishing feature of agriculture in the province. The mean size of a farm holding in the Lublin Province is 7.8 ha. The following demographic phenomena are observed in these rural areas: negative natural population increase, migration (of young women in particular), and ageing society [

27]. Agriculture in the province is predominantly traditional or supplemented with other functions. Unfavourable social phenomena exist in rural areas located further away from large urban centres. The agricultural potential of rural areas in Lublin Province is recognised as a significant local resource. The natural and cultural assets are the basis for the development of the tourist industry.

The province has a varied natural environment. Old-glacial lowlands are located in the northern part of the province, while limestone uplands are located in the central and SE parts. The south-western part of the province is an old-glacial plain (sub-Carpathian basins). Quaternary deposits create a continuous cover in the northern part of the province and within the sub-Carpathian depression. In the central part, Quaternary deposits are found mainly in river valleys and in the form of loess patches of a considerable thickness (10–20 m). Land relief in the northern part of the province is not varied; lakes and wetlands are found in the north-eastern part. Varied landforms, including numerous dry valleys with steep slopes, locally dissected by gullies, are characteristic of the central and SE part of the province. The annual precipitation volume is ca. 550 mm, the mean annual temperature ranges from 7.0 to 7.6 °C. Large continuous forest complexes are located in the southern and eastern parts of the province and north of Lublin (

Figure 2) [

28].

The intensity of land abandonment was evaluated using CORINE Land Cover data for 1990 and 2018, available on the website of the General Directorate for Environmental Protection (The Corine Land Cover 2000 project in Poland was implemented by the Chief Inspectorate for Environmental Protection. The Institute of Geodesy and Cartography was the direct contractor. The funds for the implementation of national project CLC2000 came from the European Environment Agency, National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management, and Institute of Geodesy and Cartography. The project results were obtained from the website of the Chief Inspectorate for Environmental Protection

http://clc.gios.gov.pl.) [

29]. We calculated what percentage of land under agricultural use in 1990 was used for non-agricultural purposes in 2018 in the particular counties. Data on the forest cover changes and size of anthropogenic/artificial areas (urban fabric, industrial, commercial and transport units, and mining areas) were also obtained. It must be remembered that the mapping of land cover at level 3 is carried out with an accuracy corresponding to a 1:100 000 scale map, and the area of the minimum mapping unit is 25 ha [

30].

The synthetic assessment index for agricultural production space used in this study consisted of four elements: (i) soil quality (18–95 pts.), (ii) climate (1–15 pts.), (iii) land relief (1–5 pts.), and (iv) hydrologic regime (1–5 pts.) [

26]. The value of this index ranged from 53 to 93 points in the counties under study (

Table 1). Statistical data for the counties in 2018 were obtained from the Statistical Yearbook of Lublin Province [

27].

Cluster analysis (CA) was used to analyse the correlations between the characteristics (parameters) of the counties. Cluster analysis enables the geometrical grouping of data in clusters with similar coordinates (in this case, the coordinates encompassed the characteristics of the counties). The minimum variance method was also used (Ward’s method).

Detailed investigation was completed for Susiec District, with an area of 190 km2. Soil quality and slope angle were regarded as the key natural components influencing agricultural use. The share of agricultural suitability complexes in relation to the area of arable land in the district is as follows: complex 2 (wheat, good): 1.3%; complex 3 (wheat, defective): 17.8%; complex 4 (rye, very good): 6.9%; complex 5 (rye, good): 25%; complex 6 (rye, poor): 41.2%; complex 7 (rye, very poor): 6.5%; complex 8 (cereals and fodder crops, strong): <1%; and complex 9 (cereals and fodder crops, poor): <1%.

The northern and north-eastern part of Susiec District, i.e., the area of Central Roztocze, is the most varied area from a geomorphological perspective (

Figure 3). A significant diversity of land relief also exists in the central part of the district, where sand dunes are a dominant landform. Areas with low slope angles (0–3°), i.e., plateau tops and valley bottoms, are the most extensive in the district. Their joint size is 14,100 ha (74% of the entire district). Gentle slopes (3–7°) cover 4240 ha (22% of the total area). Moderately inclined slopes (7–15°) cover 685 ha (about 3.6% of the total area of the district). Areas with steep slopes (over 15°) cover less than 1% of the total area.

The following sources were used for detailed analyses in Susiec District: (1) a 1:25,000 soil and agricultural map, (2) digital terrain model, and (3) contemporary ortophotomap. The soil and agricultural map contains information on soil capability classes and agricultural suitability complexes. The polygons in the soil and agricultural map layer were created based on a 1:25 000 soil and agricultural map from 1965. Data for preparing the Digital Elevation Model/Digital Terrain Model (DEM/DTM) for Susiec District in the ESRI (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc.) TIN format were obtained from the Main Office of Geodesy and Cartography.

In the study, similarly to Majchrowska [

32], we defined areas of land abandonment as areas: (a) where tree or grass and tree vegetation occurs as a result of natural succession; (b) that were used for agricultural purposes in the past; (c) that were not subject to deliberate afforestation. A detailed analysis of a 1:500 ortophotomap available at Geoportal (

http://geoportal.gov.pl) made it possible to distinguish three categories of land abandonment areas (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5):

Category 1: agricultural land that was abandoned during the last 10 years (2009–2019) and is overgrown by grass and low shrubs;

Category 2: agricultural land that was abandoned during the last 25 years (2009–1994) with higher shrubs and low trees;

Category 3: agricultural land that was abandoned more than 25 years ago (before 1994) and is entirely covered by trees and tall shrubs.

When assessing the rate of succession and, consequently, the duration of the abandonment of agricultural use in a given area, historical aerial photographs were used, including tools offered by Google Earth Pro. To carry out analyses of the natural determinants of the land abandonment during the last 50 years, the maps were prepared showing the following topics:

soil cover (agricultural suitability classes);

land relief (map of slope angles);

forest areas in 1965;

present-day forest areas;

areas excluded from agricultural use.

Based on these maps, the influence of (i) soil quality, (ii) slope angles, (iii) distance from forest complexes, and (iv) existing buildings on the intensity of land abandonment was analysed. The analysis consisted of determining the frequency of occurrence of areas subject to land abandonment versus the individual categories of factors mentioned above. Spatial analyses were carried out using GIS software.

3. Results

From 1990 to 2018, the area of arable land decreased in all counties of Lublin Province (

Table 1). Depending on the county, the reduction ranged from 2% (2000 ha) to 13% (11,600 ha), the mean decrease being 6.5%. This process showed considerable spatial variation. The highest intensities of land abandonment were found in the following counties: Puławy (13%), Ryki (12), Lubartów (11%), and Biłgoraj (10%). A distinctly lower intensity of this process took place in Hrubieszów (2%) and Radzyń Podlaski counties (4%). This was accompanied by an increase in the forest cover by 2% to 27% (10% on average) and an increase the size of anthropogenic areas. The share of arable land in 2018 ranged from 49% to 82% depending on the county (mean of 67%), while the forest cover ranged from 10% to 44% (mean of 23%). The migration balance was negative for all counties except for Lublin county. The internal migrations within the counties meant that people were moving from villages to towns. The mean farm holding size was the smallest in Puławy County (3.95 ha) and the largest in Parczew County (9.77 ha).

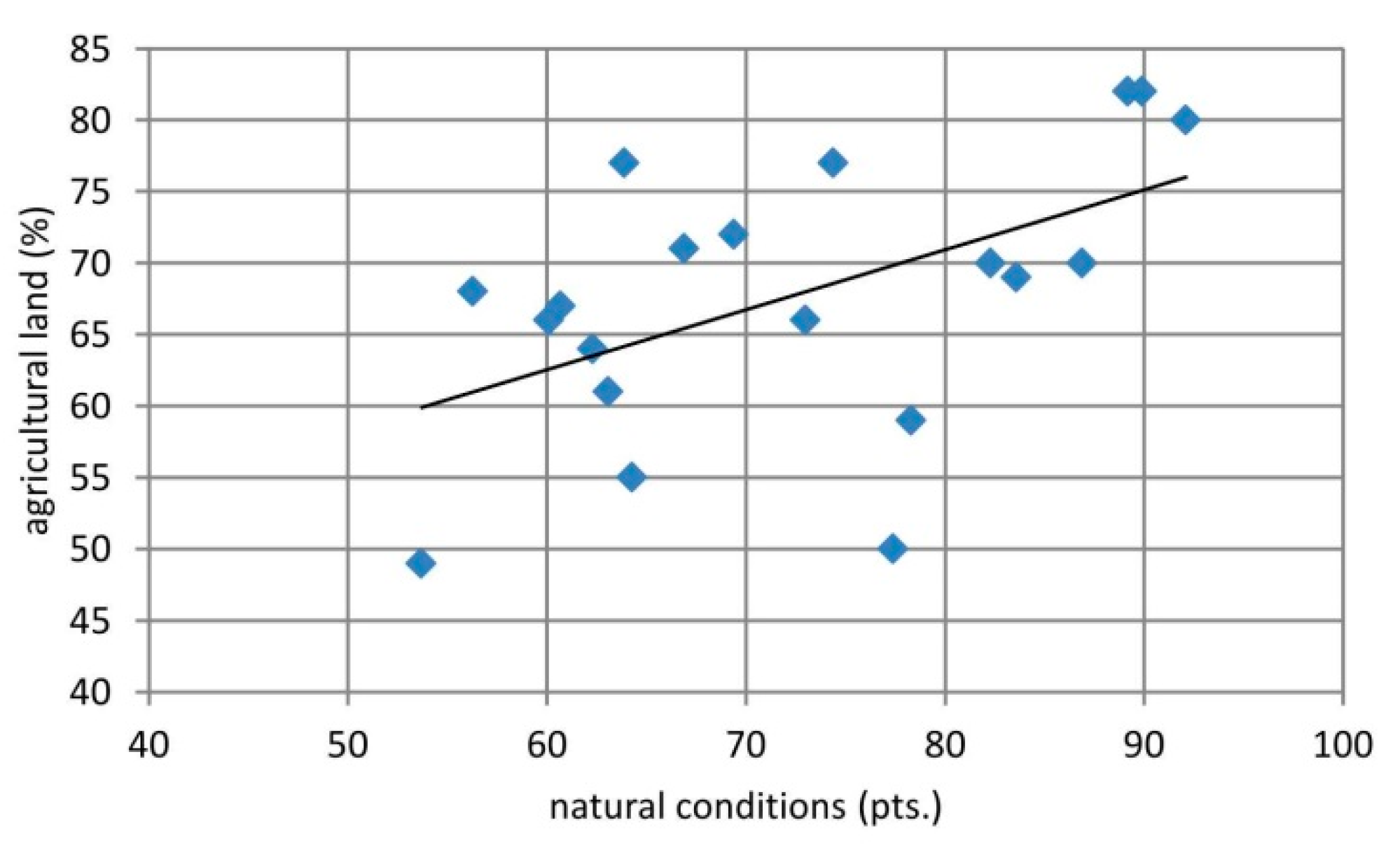

Significant correlations were found between the intensity of land abandonment and the following characteristics of the counties: changes in forest cover (correlation coefficient: 0.57), area of arable land in 2018 (0.47), mean farm holding size in 2018 (0.37), migration balance (0.36), and natural conditions (0.32) (

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8).

Using the grouping method made it possible to distinguish five groups of counties with a specific set of characteristics (

Table 1).

Group 1—Hrubieszów, Lublin, and Świdnik counties—low intensity of land abandonment, medium forest cover increase, various anthropogenic changes, the best natural conditions, very small forest cover, the biggest share of arable land, low migration balance, high population density, varying farm holding size, low level of migration to towns, and varying number of small farm holdings.

Group 2—Kraśnik, Tomaszów Lubelski, and Zamość counties—low/medium intensity of land abandonment, medium forest cover changes, big anthropogenic changes, good natural conditions, medium forest cover, medium share of arable land, medium/high migration balance, low population density, medium farm holding size, low level of migration to towns, and medium share of small farm holdings.

Group 3—Chełm, Krasnystaw, Łęczna, Opole Lubelskie, and Radzyń Podlaski counties—medium intensity of land abandonment, big forest cover changes, small anthropogenic changes, small/medium forest cover, moderate natural conditions, quite a large share of arable land, high migration balance, high population density, medium farm holding size, low level of migration to towns, and medium share of small farm holdings.

Group 4—Biała Podlaska, Lubartów, Łuków, Parczew, and Ryki counties—medium/high intensity of land abandonment, big forest cover changes, small/moderate anthropogenic changes, the poorest natural conditions, medium forest cover, small/medium share of arable land, high migration balance, low population density, medium farm holding size, high level of migration to towns, and small number of small farm holdings.

Group 5—Biłgoraj, Janów Lubelski, Puławy, and Włodawa counties—high/medium intensity of land abandonment, small forest cover changes, medium anthropogenic changes, poor natural conditions, the highest forest cover, the lowest share of arable land, medium/high migration balance, low population density, medium farm holding size, high level of migration to towns, and small share of small farm holdings (except Puławy county).

Detailed analyses conducted in Susiec District showed that most of the recently abandoned agricultural areas were located in its central and northern parts (

Figure 9). Those areas were historically used for intensive agricultural production, while the southern and south-western parts of the district are forested, and it is self-evident that land abandonment cannot occur there. The majority of areas where agricultural use was discontinued relatively recently (the last 10 years) are located in the central part of the district (

Figure 9). The areas that were first excluded from agricultural use are located primarily in the south-eastern and north-western parts of the district. Areas belonging to category 2 are scattered across the entire area of Susiec District, although most of them are in its western half.

The vast majority of abandoned land consists of rectangular plots. There were 551 plots where land abandonment took place within the district (

Table 2). The plots differ considerably in area: the smallest ones cover little more than 0.02 ha, while the largest one reaches 70 ha. The most numerous plots (nearly 350) are polygons covering less than 1 hectare (

Figure 10). The median plot size is 0.56 ha. Only 9 (out of a total of 551 polygons) are larger than 10 ha. The mean plot area is 1.65 ha. Areas excluded from agricultural use during the last 50 years cover 913 ha, which is nearly 4.8% of the area of the entire district (190 km

2) and as much as 10.7% of the arable land area in 1965. It should also be noted that only 42.15 ha, primarily of privately held land, were subjected to deliberate afforestation in the years 2003–2018 [

27].

Areas that were excluded from agricultural use relatively recently (Category 1) cover 107 ha, which accounts for 12% of the abandoned land area, while areas abandoned for more than 10–15 years account for 33%. The largest proportion of abandoned land areas are those excluded from agricultural use for the longest time (504 ha).

The largest areas of abandoned land were found within agricultural soil suitability complexes 6, 3, and 5 with 372, 155, and 131 ha, respectively. Distinctly fewer abandoned areas occur on the soils belonging to complexes 2 and 4, but they cover a distinctly smaller acreage, particularly in the case of complex 2. This process was the most intensive within complexes 7 and 6, where abandoned land accounts for 17.5% and 11.5% of their areas, respectively.

Land abandonment occurred the earliest primarily in areas of complexes 6 (238 ha), 5 (70 ha), and 7 (69 ha). This also applies to the intensity of the process within a specific complex. It was the highest for complex 7 with 13% of its area excluded from agricultural use. In the case of land abandoned 10 to 25 years ago, this process primarily was observed in complexes 3 and 6 complex (100 ha each). The process took place with the highest intensity in complexes 2 and 3. In the former case, it resulted from the small area of the complex within the district and the exclusion of one large piece of land from agricultural use. The most recent changes had the lowest intensity, but they primarily affected complexes 7 (65 ha) and 6 (32 ha).

The intensity of land abandonment in relation to the slope angle was assessed by comparing the share of areas excluded from agricultural use in relation to the entire area with a particular slope range. The calculation was carried out for all abandoned areas jointly and separately for each category of these areas (

Table 3). The intensity of the process was higher as the slope angle increased. Taking into account absolute figures, most of the abandoned land was found in areas with slopes up to 3° (530 ha), but it should be remembered that these areas occupy 74% of the district. The size of areas with slightly greater slopes (up to 7°) is one third of the areas with gentler slopes, while the size of recently abandoned land is just 40% smaller (

Figure 11). A detailed analysis shows that the area of abandoned land increases as the slope angle increases. This process occurs particularly in the central part of the district. It should be noted that the impact of slope angle is slightly greater in the case of land that was abandoned earlier.

More than half of the land excluded from agricultural use is within 100 m of the existing forest boundaries. More than three quarters of abandoned land is located within 250 m of the forest boundaries. As much as 92.6% of the recently abandoned land is within the 500 m buffer around the woodland. Only 2% of all abandoned land (18.1 ha) is within 100 m of the boundary of built-up areas. The total area of abandoned land increases with distance from that boundary. The total area of abandoned land amounts to 83.6 ha within the 250-metre buffer and 223.8 ha within the 500-metre buffer, which constitutes nearly one fourth of the total size of these areas.

4. Discussion

The process of agricultural land abandonment is currently a significant factor influencing land use and land cover changes in Europe. Identifying the intensity and, in particular, the determinants of this process is crucial from the perspective of sustainable use of natural environment resources and development of spatial policy in agricultural areas, i.e., sustainable land management and planning. It also enables assessing changes related to soil erosion, biodiversity changes, and landscape shaping [

34,

35,

36,

37].

The intensity of land abandonment in Central Europe was influenced by the character of agrarian reforms introduced as a result of the socio-economic changes of the late 1990s [

8]. The intensity of this process was low in Poland where most arable land was privately owned in socialist times and thus ownership change was unnecessary [

38]. Kuemmerle et al. [

39] studied land abandonment in the Carpathians, an 18,000 km

2 triangle formed by the borders of Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine. Based on satellite imagery, they estimated that a significant amount of arable land was abandoned between 1986 and 2000: 20.7% in Slovakia, 13.9% in Poland, and 13.3% in Ukraine. They also demonstrated that previously collectivised land in Poland was abandoned twice as often as the land that had been in private hands. At the same time, regions with small farms and highly fragmented land ownership had also experienced a considerable percentage of land abandonment during the last few decades of the 20th century [

40].

Kozak et al. [

41] observed that one third of arable land in the Beskid Mały mountains (Carpathians, southern Poland) had been abandoned in the years 1965–1997 and the process had not finished yet. The analysis of data for all of Europe showed that a moderate intensity of land abandonment in the years 2001–2012 took place in Central European countries, including Germany, Poland, and the Czech Republic as well as Ireland and the British Isles [

7]. In recent years, the intensity of this process has been falling and the reclamation of the previously abandoned arable land has recently become a major trend. The intensity of land abandonment was reduced as a result of Poland’s accession to the European Union and the resulting access to subsidies to agricultural production under the Common Agricultural Policy as well as payments for areas with unfavourable farming conditions [

7].

Secondary forest succession is widespread in Poland, although statistical data on its extent are not available. Areas subject to an early stage of secondary forest succession are frequently classified as wasteland. Plots covered with trees are usually recorded as arable land in the land register. It is assumed that forest succession prevails over afforestation. At the same time, the final outcome, i.e., the species composition and structure of forests formed as a result of secondary succession, is a big unknown [

42]. On the other hand, the planned process of afforestation has not been accelerated even by the financial instruments under the Common Agricultural Policy [

43].

The process of discontinuing agricultural production in Lublin Province is noticeable and, in the years to come, it can lead not only to significant changes in land use itself but can also have an impact on landscape. The area of land abandoned in Lublin Province in the 1990–2018 period amounts to about 131,000 ha, i.e., 7% of arable land in 1990. This process shows a high spatial variation, which suggests the role of local driving forces. External causes act as triggers of the process while internal causes impact the size of abandoned land and areas where land is abandoned. Among external factors, natural factors affect the productivity of soils and, consequently, the profitability and competitiveness of the product on offer [

23]. Such a situation occurs in Lublin Province (

Figure 12).

The intensity of land abandonment is clearly less in Lublin Province, a major agricultural region, than in Poland’s mountain regions. For example, Kolecka et al. [

44] demonstrated that while the mean intensity of this process in the Carpathians was 14% during the last few decades, the maximum intensity exceeded 30%. In small areas (districts), this index can even exceed 45% [

45].

Spatial analyses conducted in Susiec District show that the area of land excluded from agricultural use, evaluated by means of detailed analyses of aerial photographs, is considerably underestimated in comparison to CORINE Land Cover (CLC) data. Since the smallest area distinguished for the CLC inventory is 25 ha, it can be used to identify only 247 ha, which represent only 27% of all land that was actually abandoned. This results from the presence of a large number of small plots subject to land abandonment. These plots are so small that they are not recorded in small-scale maps [

29,

46]. Kolecka and Kozak [

37] mentioned the difficulty of determining the actual intensity of this process due to its dispersed character and a certain subtlety of changes. The use of LiDaR data is surely a method that will enable very detailed studies in this respect [

47,

48].

The analysis of correlations between the statistical characteristics of the counties (

Table 1) indicate that the following factors resulted in the spatial variation of the intensity of land abandonment in Lublin Province in the years 1990–2018: (i) natural conditions of agricultural production; (ii) intensity of the agricultural use of space; (iii) forest cover; (iv) number of small farm holdings; and (v) intensity of external migration. The process of land abandonment finally results in an increased forest cover and, to a smaller extent, the conversion of arable land into built up areas. The role of factors such as farm holding size, natural conditions (soils), and migration balance in the present-day land abandonment processes in Poland’s metropolitan areas was highlighted in [

49]. Kolecka et al. [

37] indicate natural conditions (slope angle) and employment opportunities outside agriculture as the key factors determining land abandonment in the Polish Carpathians.

Since land abandonment results from the joint effect of several factors, it is not easy to find clear statistical correlations between the intensity of the process and the individual characteristics of the counties [

50]. It should be added that in both cases, these characteristics show spatial differences, and providing one mean value for the whole entity is a far-reaching simplification. Nonetheless, the set of characteristics favourable or unfavourable to this process can be identified in the case of a few counties. It should be noted that such correlations did not occur for other counties, which may result from, for example, the considerable spatial diversity of the environment or socio-economic characteristics within those districts.

(a) Hrubieszów County has the smallest intensity of land abandonment, very good natural conditions, large share of arable land, relatively large farm holdings, and a high negative migration balance;

(b) Puławy County has the highest intensity of land abandonment, quite good natural conditions, the smallest mean farm holding size, and many migrations from villages to towns;

(c) Ryki County has a high intensity of land abandonment, relatively poor natural conditions, and a high level of migrations from villages to towns.

The analyses show that counties with a higher intensity of land abandonment usually absorbed the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) funds to a smaller extent (

Figure 13). This is clear in the case of instruments aimed at changing (improving) the structure of agricultural production and agrarian structure (

Table 4). On the other hand, instruments related to the improvement of productivity and profitability as well as socio-demographic characteristics are used effectively in counties with a low and medium intensity of land abandonment. The lowest absorption of CAP funds was observed in counties located close to large cities (Lublin, Chełm, and Lubartów counties) or counties with significant shares of protected areas and forests (Włodawa and Biłgoraj counties).

It should be mentioned that in the case of Lubelskie Voivodship in the period 2004–2010, the average payments for one ha under individual programs was as follows: pro-environmental instruments (180 EUR), improvement of agrarian structure (60 EUR), improvement of socio-economical features (90 EUR), improvement of technical infrastructure (110 EUR), modernization of agricultural production (452 EUR), and improvement of profitability (35 EUR) [

48]. Together with the Single Area Payment Scheme (about 200 EUR per ha per year), on average, a farmer in Lubelskie Province received a total of about 2500 EUR per ha during this period. Therefore, the funds that can be obtained by individual farmers are not large (less than 2700 EUR per average farm per year). Family farms cannot further develop, for example by purchasing equipment or improving the conditions for agricultural production (fertilization, terracing). The amount of the CAP payments is therefore not an incentive for continuing land cultivation.

Detailed analyses show that more than 10% of arable land was excluded from agricultural use in Susiec District during the last 50 years. The dynamics of this process have reduced but the process continues. Land relief, on the other hand, has an impact on the process of agricultural abandonment. This process is clearly more intensive in areas with greater slope angles. Land is excluded from agricultural use most often in areas with 7–12° slopes. Areas with greater slope angles are largely forested, hence land abandonment is less intensive there. A very distinct influence of land relief (primarily slope angles) on present-day land-use in the loess areas in SE Poland was indicated by Zgłobicki and Baran-Zgłobicka [

52]. The role of slope angle and elevation above sea level on the spatial distribution of forests was also noted in research conducted in China, Germany, Czech Republic, and many European countries [

17,

53,

54].

The soil type had the greatest influence on the exclusion of land from agricultural production in Susiec District. This process occurred with a lower intensity on fertile soils (complexes 2 and 3, Luvisols and Cambisols) than on poor soils (complexes 5 and 6, sandy Podzols). Wulf et al. [

55] found a clear relationship between changes in the forest cover and soils in north-eastern Germany. Reforestation processes occurred primarily within less productive sandy soils. The same patterns were found by Zgłobicki et al. [

20]. Keenleyside and Tucker [

47] identified poor soil quality as a significant factor influencing land abandonment. Poor soils mean low crop yields, which lead to low profits for the farmers. On the other hand, studies in Małopolska made by Busko and Szafrańska [

56] indicated that top quality arable soils were also converted to non-agricultural use.

More than half of the area of Susiec District is covered by forests. The results of the analyses above indicate that a large part of the areas excluded from agricultural use are located close to the forest boundary. Most of them ceased to be used for agricultural purposes at least 25 years ago because the vegetation occurring there consists mainly of trees and high shrubs. Similar patterns were found in the case of analyses carried out for the counties, greater forest cover was usually conducive to land abandonment. Similar conclusions were reached by Zgłobicki et al. [

20] who studied the determinants of forest cover changes in Lublin Province during the last 180 years. A decreased need for agricultural land and shift to forested areas was also observed in the northern Czech Republic [

57].

The influence of natural conditions on the process of land abandonment in Susiec District, as demonstrated in this study, is modified by very local social and economic factors that cannot always be analysed in spatial terms. There is no doubt that being a large distance from built-up areas can lead farmers to decide to stop cultivating the land. This is particularly visible in the situation of the considerable fragmentation of land within a single farm holding. The analyses conducted in this study show that plots located close to built-up areas are excluded from agricultural use more rarely than those lying further away.

The increased size of forest areas as a result of land abandonment is advantageous from the perspective of flood, soil, and gully erosion prevention [

58,

59,

60]. For example, Zgłobicki and Baran-Zgłobicka [

61] estimated that land cover changes (mainly afforestation) within Wąwolnica District (Lublin Province) in the 1962–1997 period had led to a 20–25% reduction of the amount of material transported due to soil erosion. Latocha et al. [

62] reported that land abandonment in the Sudetes resulted in the mean reduction of soil erosion intensity by 3 t ha

−1 y

−1 (locally by 8–16 t ha

−1 y

−1). The abandonment of agricultural land adjoining gullies clearly reduces the dynamics of the geomorphological processes occurring there [

63]. Positive effects of the process also include increased carbon sequestration through vegetation regrowth [

64] and reduced emissions and chemical pollution because of the reduced usage intensity of fertiliser and crop-protection products applications [

2].

However, a spontaneous and uncontrolled reforestation is not entirely advantageous because it threatens the traditional cultural landscape and can contribute to a reduction of biodiversity [

63]. Terres et al. [

5] confirm that land abandonment can be perceived as an opportunity for restoring land to the state preceding its agricultural use. They observe, however, that many ecosystems in Europe have developed in the presence of agriculture, and the discontinuation of land cultivation can have considerable unfavourable ecological effects. The mosaic of fields, a traditional feature of the landscape in southern Poland, is lost due to mass-scale land abandonment [

65,

66]. Additionally, burning vegetation in abandoned areas poses a risk of forest fires. However, the intensity of these phenomena has yet to be studied.

From the perspective of shaping the spatial structure of agricultural areas and sustainable use of agricultural space in Poland, the legal framework and EU funds are of fundamental importance. The Act on the Shaping of the Agricultural System [

67] seeks to support family farms and sustainable agriculture that complies with the environmental protection requirements and is conducive to the development of rural areas. Its provisions primarily govern the principles of agricultural property trade (except for properties smaller than 0.3 ha). It adopts the definition of a farm holding “as defined in the Civil Code according to which the area of an agricultural property or total area of agricultural properties is not smaller than 1 ha”. The Act on the Protection of Arable and Forest Land [

68] is important in the context of preserving the resources of agricultural production space because its main goal is to protect arable and forest land against land use change. The scope of actions concerning the development of space is defined by the Act on Spatial Planning and Development [

69] that grants special powers to local authorities and gives district governments autonomy with regard to planning. At the same time, planning documents must take into account the needs of nature and landscape conservation, natural environment preservation, protection of agricultural and forest production space, flood control, etc. In the current legal situation, specific areas can be earmarked for afforestation, while the process of abandoning the cultivation fields cannot be controlled. The only formal instrument is to maintain the agricultural purpose of land in planning documents, particularly in local spatial development plans. This, however, does not translate into the actual state of the land.

The mean area of arable land in farm holdings, calculated based on applications for area-based payments, increased from 9.91 ha in 2007 to 10.95 in 2019 nationwide, and from 7.28 ha in 2007 to 7.93 ha in 2019 in Lublin Province (

https://www.arimr.gov.pl). The low rate of farm holding size increase results primarily from the economic situation. This situation persists primarily due to factors such as the ageing society, absence of young farmers who would develop their farm holdings, and better conditions of social security for farmers [

70] in the Agricultural Social Insurance Fund (KRUS) than in the Social Insurance Institution (ZUS). It is particularly important in the case of non-agricultural economic activity as the owner of a farm holding of 1 ha may be insured in KRUS. At the same time, rural districts apply lower property tax rates. Therefore, individuals who own a small area of arable land and have other sources of income do not conduct agricultural activity. In many cases, agricultural plots are treated as capital investments, particularly given the possibility of converting them into building plots, which is relatively easy in the case of poor soils [

70].

Traditional agricultural landscapes characterised by a large diversity of ecosystems predominate in south-eastern Poland. The mosaic of small-area crops is complemented by field ridges and woodlots, meadows and pastures, and natural ecosystems such as small ponds, peat bogs, and xerothermic grassland. The greater the diversity of ecosystems, the greater their biodiversity and ability to self-regulate [

71,

72]. According to Rudnicki [

51], in Lubelskie Province forests, fallow land and permanent grasslands cover about 24% of the area of the agricultural holdings.

Polish farmers are generally not perceived in the state policy and strategic documents as participants in the green economy. In the Rural Development Program there is a reference to the “green economy” in individual packages, but widespread participation in them is not possible. Different economic instruments (funds from CAP) are used to stimulate non-production functions of agriculture, which include protection of landscape values, maintenance of biodiversity, protection of soils and waters, and maintenance of extensive pastures and meadows. It seems that the multifunctional agriculture model is partly reflected in the decisions taken by Polish farmers. However, their intensity varies regionally, it seems that their use of funds is not very large due to the ownership structure of farms in Lubelskie Province [

73]. The possibility of receiving such funds depends on the need to meet many conditions.

At present, two trends can be observed in Poland’s agricultural landscapes. The first trend is manifested in the decreasing diversity as a result of intensified agricultural production, increasing plot sizes and farm holdings, and reduction of livestock grazing, which leads to a simplified spatial structure and monotony of landscapes [

72]. The second trend can be observed primarily in peripheral areas, Lubelskie Province for example, where socio-economic problems and lack of a sufficiently good potential for agricultural production lead to the abandonment of cultivation, which, in turn, results in a reduced biodiversity of species associated with agrocenoses. The phenomenon of long-term fallowing of arable land enables the development of shrublands and woodlots and leads to changes in the physiognomy of the landscape. This problem also concerns permanent grasslands [

74].

The still large share of small, extensive farm holdings forming the mosaic of land use that enhances the value of landscapes is definitely an advantage of agriculture in Poland [

75]. On the other hand, this land use structure is regarded as an obstacle to development in the context of economic efficiency. At the same time, the unification of landscape as a result of land consolidation and simplification of crop rotation is recognised as a threat to rural areas [

76].

5. Conclusions

Land abandonment is a significant process shaping the environment of Lublin Province. In the years 1990–2018, ca. 7% of land was excluded from agricultural use, which caused a ca. 10% increase in the area covered by forests. The dynamic of land abandonment has been decreasing in recent years.

The processes taking place can be regarded as rational from an economic perspective because land abandonment occurs in areas of the lowest value for agricultural production (high slope angles, poor soils). It should be noted, however, that these processes result from the individual decisions taken by farmers rather than from a deliberate policy.

The socio-economic factors influencing the intensity of the process include the intensity of the agricultural use of a particular area, the percentage of small farm holdings in relation to the total number of farm holdings, and the intensity of migration processes. At the local scale, the distance of the fields from the settlement network is also a factor. It has also been observed that the intensity of land abandonment is influenced to some extent by the absorption of Common Agricultural Policy funds. Land abandonment is usually more intensive when the absorption of funds is more limited. However, this pattern has not been observed for all kinds of funding schemes.

Detailed spatial analyses indicated that land abandonment usually occurs in small areas unevenly distributed across a larger territory. The intensity of this process is larger than what analyses based on small-scale data (e.g., CLC) would suggest.

Forest cover increase resulting from land abandonment reduces the threat of soil erosion processes and local flooding, particularly in areas with greater slope angles. At the initial stage, this also contributes to increased biodiversity as well as a decrease in the number of species associated with agrocenoses. On the other hand, intensive reforestation can lead to the disappearance of the traditional mosaic-like agricultural landscape.

Poland lacks legal regulations governing the processes of discontinuing agricultural land use. What is more, this phenomenon is not monitored, and there are no data concerning its spatial diversity and temporal variation. Studies on the influence of this kind of land-use changes on biodiversity and landscape value are not comprehensive; they are usually based on single case studies. Given the scale of this phenomenon, it is necessary to conduct further studies on the intensity of land abandonment and, most of all, on its environmental and socio-economic consequences.