The Impact of Organizational Dysfunction on Employees’ Fertility and Economic Outcomes: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objectives and Research Questions

- How does organizational dysfunction affect employees’ fertility outcomes and reproductive health?

- What organizational factors most significantly hinder reproductive health in the workplace?

- What are the economic and productivity costs associated with insufficient support for fertility?

- Which workplace accommodations and policies have been shown to improve fertility-related outcomes?

- How do stigma and organizational culture influence employees’ willingness to disclose or seek support?

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

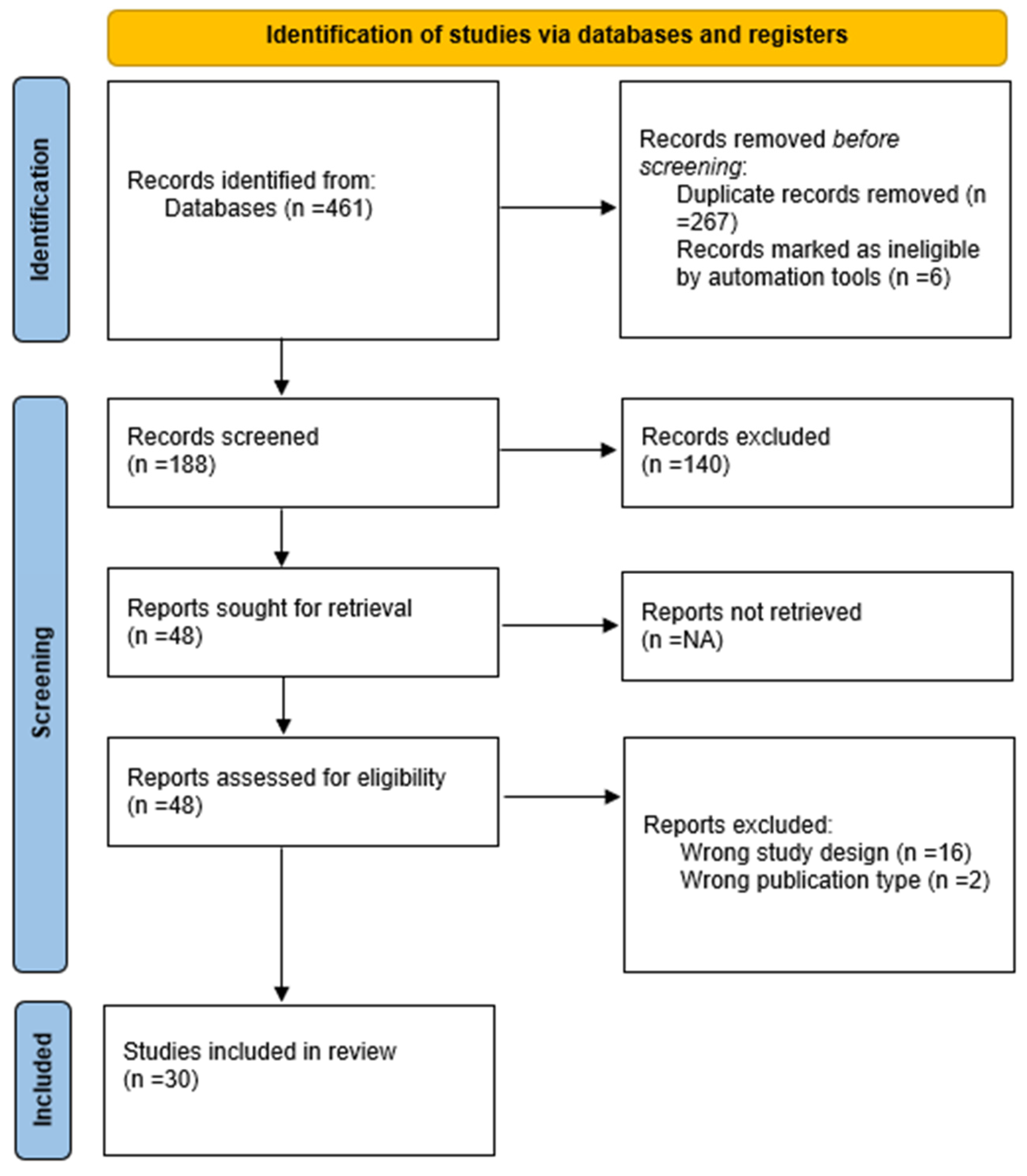

2.4. Study Selection

- Title and Abstract Screening: Two reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts to determine initial relevance according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in the PCC framework (see Table 1). Studies that did not meet the basic eligibility requirements were excluded at this stage.

- Full-Text Review: Full texts of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussion.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Synthesis of Research Questions

- Impact of organizational dysfunction on fertility and reproductive health

- 2.

- Organizational barriers to reproductive well-being

- 3.

- Economic and productivity consequences of inadequate support

- 4.

- Effective organizational accommodations and policy interventions

3.3. Role of Stigma and Organizational Culture in Disclosure and Support-Seeking

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, M., & Goldman, R. H. (2020). Occupational reproductive hazards for female surgeons in the operating room. JAMA Surgery, 155(3), 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijo, P. R., Flores, L., Huynh, L., Strong, S., Mukkamala, S., & Shillcutt, S. (2021). Fertility and reproductive health in women physicians. Journal of Women’s Health, 30(12), 1713–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babanov, S. A., Strizhakov, L. A., Agarkova, I. A., Tezikov, Y. V., & Lipatov, I. S. (2019). Workplace factors and reproductive health: Causation and occupational risks assessment. Gynecology, 21(4), 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranski, B. (1993). Effects of the workplace on fertility and related reproductive outcomes. Environmental Health Perspectives, 101(Suppl. S2), 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzilai-Pesach, V., Sheiner, E. K., Sheiner, E., Potashnik, G., & Shoham-Vardi, I. (2006). The effect of women’s occupational psychologic stress on outcome of fertility treatments. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 48(1), 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billingsley, S., & Ferrarini, T. (2014). Family policy and fertility intentions in 21 European countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(2), 428–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisanti, L., Olsen, J., Basso, O., Thonneau, P., & Karmaus, W. (1996). Shift work and subfecundity: A European multicenter study. European study group on infertility and subfecundity. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 38(4), 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, J., & Schmidt, L. (2005). Infertility-related stress in men and women predicts treatment outcome 1 year later. Fertility and Sterility, 83(6), 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmans, C. A. M., Lintsen, B. A. M. E., Al, M., Verhaak, C. M., Eijkemans, R. J. C., Habbema, J. D. F., Braat, D. D. M., & Hakkaart-Van Roijen, L. (2008). Absence from work and emotional stress in women undergoing IVF or ICSI: An analysis of IVF-related absence from work in women and the contribution of general and emotional factors. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 87(11), 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugiavini, A., Pasini, G., & Trevisan, E. (2013). The direct impact of maternity benefits on leave taking: Evidence from complete fertility histories. Advances in Life Course Research, 18(1), 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budig, M. J., Misra, J., & Boeckmann, I. (2012). The motherhood penalty in cross-national perspective: The importance of work-family policies and cultural attitudes. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 19(2), 163–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, G., Bozinovic, I., Dupont, C., Léger, D., Lévy, R., & Sermondade, N. (2021). Impact of sleep on female and male reproductive functions: A systemati c review. Fertility and Sterility, 115(3), 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Angeles, M., Atkinson, R. B., Easter, S. R., Gosain, A., Hu, Y.-Y., Cooper, Z., Kim, E. S., Fromson, J. A., & Rangel, E. L. (2022). Postpartum depression in surgeons and workplace support for obstetric and neonatal complication: Results of a national study of US surgeons. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 234(6), 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castles, F. G. (2003). The world turned upside down: Below replacement fertility, changing preferences and family-friendly public policy in 21 OECD countries. Journal of European Social Policy, 13(3), 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cech, E. A., & O’Connor, L. T. (2017). ‘Like second-hand smoke’: The toxic effect of workplace flexibility bi as for workers’ health. Community, Work & Family, 20(5), 543–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervi, L., & Knights, D. (2022). Organizing male infertility: Masculinities and fertility treatment. Gender, Work & Organization, 29(4), 1113–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, Y. M., West, S., & Mapedzahama, V. (2013). Night work and the reproductive health of women: An integrated literature review. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 59(2), 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S., Yellow Horse, A. J., & Yang, T.-C. (2018). Family policies and working women’s fertility intentions in South Korea. Asian Population Studies, 14(3), 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S., Cox, T., & Pryce, J. (2000). Work-related reproductive health: A review. Work & Stress, 14(2), 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehkordi, S. M., Khoshakhlagh, A. H., Yazdanirad, S., Mohammadian-Hafshejani, A., & Rajabi-Vardanjani, H. (2025). The effect of job stress on fertility, its intention, and infertility treatment among the workers: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Trigo, B. R., De Oliveira Trigo, A., Folgado, J., & Lucas, C. (2023). P-576 The perspective of patients and company leaders regarding fertility support in the workplace in Portugal. Human Reproduction, 38(Suppl. S1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, S., & Patel, M. (2012). The economic impact of infertility on women in developing countries—A systematic review. Facts, views & vision in ObGyn, 4(2), 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, R., Marino, J., Varcoe, T., Davis, S., Moran, L., Rumbold, A., Brown, H., Whitrow, M., Davies, M., & Moore, V. (2016). Fixed or rotating night shift work undertaken by women: Implications for fertility and miscarriage. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 34(02), 074–082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Pineda, M., Black, E. R., & Swift, A. (2025). Secondary qualitative analysis of the effect of work-related stress on women who experienced miscarriage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 54, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figa-Talamanca, I. (2006). Occupational risk factors and reproductive health of women. Occupational Medicine, 56(8), 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, K. L., Resuehr, D., & Johnson, C. H. (2013). Shift work and circadian dysregulation of reproduction. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacola, G. P. (1992). Reproductive hazards in the workplace. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 47(10), 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gifford, B., & Zong, Y. (2017). On-the-job productivity losses among employees with health problems. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 59(9), 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, S. L., Dimoff, J. K., Brady, J. M., Macleod, R., & McPhee, T. (2023). Pregnancy loss: A qualitative exploration of an experience stigmatized in the workplace. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 142, 103848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, J., & Fujimoto, T. (1995). Employer characteristics and the provision of family responsive policies. Work and Occupations, 22(4), 380–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, L. (2025). Understanding the impact of stress on infertility: Biological links an d treatment strategies. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 15(1), 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, E. B., & Tomich, E. (1994). Occupational hazards to fertility and pregnancy outcome. Occupational Medicine, 9(3), 435–469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Győrffy, Z., Dweik, D., & Girasek, E. (2014). Reproductive health and burn-out among female physicians: Nationwide, representative study from Hungary. BMC Women’s Health, 14(1), 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauser, R., Skakkebaek, N. E., Hass, U., Toppari, J., Juul, A., Andersson, A. M., Kortenkamp, A., Heindel, J. J., & Trasande, L. (2015). Male reproductive disorders, diseases, and costs of exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the European Union. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 100(4), 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, N., Brinson, A., Karwa, S., & Jahnke, H. R. (2025). Use of a digital health benefit to maintain employees’ productivity while trying to conceive. Social Science & Medicine, 382, 118329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herweck, A. M., Delawalla, M. L. M., Reed, C., Carson, T. L., Ahuja, A., Chey, P., McNamara, M., Gupta, K., Bosch, A., Hipp, H. S., & Kawwass, J. F. (2025). Enhancing reproductive access: The influence of expanded employer fertility benefits at a single academic center from 2017 to 2021. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hideg, I., Krstic, A., Trau, R. N. C., & Zarina, T. (2018). The unintended consequences of maternity leaves: How agency interventions mitigate the negative effects of longer legislated maternity leaves. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(10), 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C., Duxbury, L., & Julien, M. (2014). The relationship between work arrangements and work-family conflict. WORK: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation, 48(1), 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvala, T., & Hammarberg, K. (2025). The impact of reproductive health needs on women’s employment: A qualitative insight into managing endometriosis and work. BMC Women’s Health, 25(1), 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, J. C. (2008). Infertility coverage is good business. Fertility and Sterility, 89(5), 1049–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, N., Aminian, O., Ghafourian, K., Aghdaee, A., & Samadanian, S. (2024). Reproductive outcomes among female health care workers. BMC Women’s Health, 24(1), 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, D., & Whirledge, S. (2017). Stress and the HPA axis: Balancing homeostasis and fertility. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 18(10), 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jou, J., Kozhimannil, K. B., Blewett, L. A., McGovern, P. M., & Abraham, J. M. (2016). Workplace accommodations for pregnant employees. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 58(6), 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, K., Pabayo, R., Critchley, J. A., & Bambra, C. (2010). Flexible working conditions and their effects on employee health and wellbeing. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. J., & Parish, S. L. (2020). Family-supportive workplace policies and benefits and fertility intent ions in South Korea. Community, Work & Family, 25(4), 464–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. (2004). Occupational exposure associated with reproductive dysfunction. Journal of Occupational Health, 46(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lwin, T. M., Castillo-Angeles, M., Cunningham, C. E., Atkinson, R. B., Kim, E., Easter, S. R., Gosain, A., Hu, Y.-Y., & Rangel, E. L. (2024). The impact of low workplace support during pregnancy on surgeon distress and career dissatisfaction. Annals of Surgery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubykh, Z., Turner, N., Weinhardt, J. M., Davis, J., & Dumaisnil, A. (2025). Facilitating mental health disclosure and better work outcomes: The Role of organizational support for disclosing mental health concerns. Human Resource Management, 64, 1243–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, E., Hiraike, O., Sugimori, H., Kinoshita, A., Hirao, M., Nomura, K., & Osuga, Y. (2022). Working conditions contribute to fertility-related quality of life: A cross-sectional study in Japan. Reproductive BioMedicine Online, 45(6), 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, M. M. (2010). Shift work, jet lag, and female reproduction. International Journal of Endocrinology, 2010, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, A., Vekved, M., & Tough, S. (2011). P1-242 Impact of work place policies and educational attainment on women’s childbearing decisions in Canada. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 65(Suppl. S1), A133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mills, J., & Kuohung, W. (2019). Impact of circadian rhythms on female reproduction and infertility treatment success. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes & Obesity, 26(6), 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirick, R. G., & Wladkowski, S. P. (2022). Infertility and pregnancy loss in doctoral education: Understanding students’ experiences. Affilia, 38(3), 503–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mínguez-Alarcón, L., Souter, I., Williams, P. L., Ford, J. B., Hauser, R., Chavarro, J. E., & Gaskins, A. J. (2017). Occupational factors and markers of ovarian reserve and response among women at a fertility centre. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 74(6), 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moćkun-Pietrzak, J., Gaworska-Krzemińska, A., & Michalik, A. (2022). A cross-sectional, exploratory study on the impact of night shift work on midwives’ reproductive and sexual health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 8082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motaung, L. L., Bussin, M. H. R., & Joseph, R. M. (2017). Maternity and paternity leave and career progression of black African women in dual-career couples. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 1(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachtigall, R. D., Tschann, J. M., Quiroga, S. S., Pitcher, L., & Becker, G. (1997). Stigma, disclosure, and family functioning among parents of children conceived through donor insemination. Fertility and Sterility, 68(1), 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepomnaschy, P. A., Sheiner, E., Mastorakos, G., & Arck, P. C. (2007). Stress, immune function, and women’s reproduction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1113(1), 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, N., Seenan, S., & van den Akker, O. (2018). Experiences and psychological distress of fertility treatment and employment. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 40(2), 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2021). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation, 19(1), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D., Peters, M. D. J., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Alexander, L., Tricco, A. C., Evans, C., De Moraes, É. B., Godfrey, C. M., Pieper, D., Saran, A., Stern, C., & Munn, Z. (2022). Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 21(3), 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzo, S., Wickham, A., Bamford, R., Radovic, T., Zhaunova, L., Peven, K., Klepchukova, A., & Payne, J. L. (2022). Menstrual cycle-associated symptoms and workplace productivity in US employees: A cross-sectional survey of users of the Flo mobile phone app. Digital Health, 8, 205520762211458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangel, E. L., Castillo-Angeles, M., Hu, Y.-Y., Gosain, A., Easter, S. R., Cooper, Z., Atkinson, R. B., & Kim, E. S. (2022). Lack of workplace support for obstetric health concerns is associated with major pregnancy complications. Annals of Surgery, 276(3), 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayyan. (2024, August 7). Available online: https://www.rayyan.ai/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Rim, K.-T. (2017). Reproductive toxic chemicals at work and efforts to protect workers’ health: A literature review. Safety and Health at Work, 8(2), 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbath, E. L., Willis, M. D., Wesselink, A. K., Wang, T. R., McKinnon, C. J., Hatch, E. E., & Wise, L. A. (2024). Association between job control and time to pregnancy in a preconception cohort. Fertility and Sterility, 121(3), 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa-Cruz, D. C., & Agudo, D. (2020). Impact of underlying stress in infertility. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 32(3), 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A., & Sellix, M. T. (2016). The circadian timing system and environmental circadian disruption: From follicles to fertility. Endocrinology, 157(9), 3366–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifrin, N. V., & Michel, J. S. (2021). Flexible work arrangements and employee health: A meta-analytic review. Work & Stress, 36(1), 60–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreffler, K. M. (2016). Contextual understanding of lower fertility among U.S. women in professional occupations. Journal of Family Issues, 38(2), 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, K., Meletiche, D., & Del Rosario, G. (2009). An employer’s experience with infertility coverage: A case study. Fertility and Sterility, 92(6), 2103–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoens, S., Dunselman, G., Dirksen, C., Hummelshoj, L., Bokor, A., Brandes, I., Brodszky, V., Canis, M., Colombo, G. L., DeLeire, T., Falcone, T., Graham, B., Halis, G., Horne, A., Kanj, O., Kjer, J. J., Kristensen, J., Lebovic, D., Mueller, M., … D’Hooghe, T. (2012). The burden of endometriosis: Costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Human Reproduction, 27(5), 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, P., O’Neill, C., Simpson, A. J., & Lashen, H. (2007). The relationship between perceived stigma, disclosure patterns, support and distress in new attendees at an infertility clinic. Human Reproduction, 22(8), 2309–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sominsky, L., Hodgson, D. M., McLaughlin, E. A., Smith, R., Wall, H. M., & Spencer, S. J. (2017). Linking stress and infertility: A novel role for ghrelin. Endocrine Reviews, 38(5), 432–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonika. (2020). Women reproductive health and occupational safety: A literature review. Journal of Womens Health, 9, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, N. B., & Foti, T. R. (2020). Health insurance for infertility services: It’s about where you work, more than where you live. Fertility and Sterility, 114(3), e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, J. (2016). The long-run effects of wage replacement and job protection: Evidence from two maternity leave reforms in Great Britain. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, F., Kearns, B., Pericleous-Smith, A., & Imogen, C. (2024). P-455 Exploring the impact of fertility care on the modern workforce: Key research findings. Human Reproduction, 39(Suppl. S1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, F., Sizer, A., & Pericleous-Smith, A. (2022). P-486 Fertility in the workplace: The emotional, physical and psychological impact of infertility in the workplace. Human Reproduction, 37(Suppl. S1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, D., & Schernhammer, E. (2019). Does night work affect age at which menopause occurs? Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes & Obesity, 26(6), 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, L. J., Macklon, N. S., Cheong, Y. C., & Bewley, S. J. (2014). Influence of shift work on early reproductive outcomes. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 124(1), 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, K. E., & Dewa, C. S. (2014). Employee decision-making about disclosure of a mental disorder at work. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 24(4), 732–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Akker, O. B. A., Payne, N., & Lewis, S. (2017). Catch 22? Disclosing assisted conception treatment at work. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 10(5), 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgillito, D., Catalfo, P., & Ledda, C. (2025). Wearables in healthcare organizations: Implications for occupational health, organizational performance, and economic outcomes. Healthcare, 13(18), 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, G., & Chung, F. (2011). Working conditions associated with ovarian cycle in a medical center nurses: A Taiwan study. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 9(1), 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S., & Tan, J. (2024). Negotiating work and family spheres: The dyadic effects of flexible work arrangements on fertility among dual-earner heterosexual couples. Demography, 61(4), 1241–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J. R., Adams, G. A., Maranto, C. L., Sawyer, K., & Thoroughgood, C. (2017). Workplace contextual supports for LGBT employees: A review, meta-analysis, and agenda for future research. Human Resource Management, 57(1), 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winker, R., & Rüdiger, H. W. (2005). Reproductive toxicology in occupational settings: An update. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 79(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaw, A., McLane-Svoboda, A., & Hoffmann, H. (2020). Shiftwork and light at night negatively impact molecular and endocrine timekeeping in the female reproductive axis in humans and rodents. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(1), 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. L., Hjollund, N. H., Boggild, H., & Olsen, J. (2003). Shift work and subfecundity: A causal link or an artefact? Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60(9), e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Description | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Employed adults of reproductive age | Studies including adult workers (≥18 years), regardless of sex or gender, employed in any sector, and reporting reproductive, fertility, or pregnancy-related outcomes | Studies involving only unemployed individuals, students, retirees, or populations not engaged in formal employment |

| Concept | Organizational factors affecting reproductive, fertility, and economic outcomes | Studies examining the influence of organizational dysfunctions (e.g., workload, shift work, lack of support) or workplace accommodations/policies on reproductive health, fertility outcomes, or work performance/productivity | Studies not addressing organizational or workplace dimensions, or not reporting reproductive/fertility-related or economic/work outcomes |

| Context | Formal employment settings across sectors and regions | Studies conducted in formal work environments (any profession, industry, or geographic region) | Studies in informal or unpaid work contexts (e.g., homemaking, student populations, and volunteers) |

| Database | Search Terms/Strategy | Filters Applied |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“organizational dysfunction”[Title/Abstract] OR “workplace policies”[Title/Abstract] OR “workplace accommodations”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“fertility”[Title/Abstract] OR “reproductive health”[Title/Abstract] OR “infertility”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“employment”[Title/Abstract] OR “working adults”[Title/Abstract] OR “employees”[Title/Abstract]) | Language: English; Years: 1990–2025 |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“organizational dysfunction” OR “workplace policy” OR “workplace accommodation”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“fertility” OR “reproductive health” OR “infertility”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“employment” OR “working adults” OR “employees”) | Document Type: Article; Language: English; Years: 1990–2025 |

| Web of Science | TS = (“organizational dysfunction” OR “workplace policies” OR “accommodation”) AND TS = (“fertility” OR “reproductive health” OR “infertility”) AND TS = (“employment” OR “working adults” OR “employees”) | Language: English; Timespan: 1990–2025 |

| PsycINFO | (“organizational dysfunction” OR “workplace policies” OR “accommodation”) AND (“reproductive health” OR “fertility” OR “infertility”) AND (“employment” OR “employees”) | Peer-reviewed only; Language: English; Years: 1990–2025 |

| CINAHL | (TI “organizational dysfunction” OR TI “workplace policies” OR TI “accommodation”) AND (TI “fertility” OR TI “reproductive health” OR TI “infertility”) AND (TI “employment” OR TI “working adults” OR TI “employees”) | Language: English; Published 1990–2025 |

| Google Scholar | allintitle: “workplace” AND (“fertility” OR “reproductive health”) AND (“organizational dysfunction” OR “accommodation”) AND “employment” | First 100 results screened manually; English; 1990–2025 |

| Study | Study Design | Population | Workplace Factors | Primary Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Anderson & Goldman, 2020) | Quantitative (retrospective studies) | Female surgeons | Operating room hazards, working conditions | Infertility, pregnancy complications |

| (Armijo et al., 2021) | Quantitative (survey) | 377 women physicians | Training demands, work hours, breastfeeding support | Childbearing trends, fertility issues, barriers |

| (Barzilai-Pesach et al., 2006) | Quantitative (prospective cohort) | 75 working women (fertility problem) | Job stress, workload, satisfaction | Fertility treatment outcomes |

| (Castillo-Angeles et al., 2022) | Quantitative (survey) | 692 female surgeons with live births | Workplace support for work reduction during pregnancy/neonatal complications | Postpartum depression, income loss |

| (De Oliveira Trigo et al., 2023) | Mixed methods | 107 workers, 24 employers (Portugal) | Fertility-friendly policies, support | Career progression, anxiety, disclosure |

| (Fernandez-Pineda et al., 2025) | Qualitative (interviews) | 13 women post-miscarriage | Work-related stress, accommodations, support | Emotional distress, work performance |

| (Gilbert et al., 2023) | Qualitative (interviews) | 29 working women | Pregnancy loss, workplace stigma, support | Work outcomes, well-being, return-to-work |

| (Győrffy et al., 2014) | Quantitative (survey) | 3039 female physicians (Hungary) | Burnout, workload | Reproductive disorders, burnout |

| (Herweck et al., 2025) | Quantitative (retrospective) | 1586 patients at an academic center | Expanded fertility benefits | Access, utilization, demographics |

| (Hvala & Hammarberg, 2025) | Qualitative (interviews) | 12 employed women with endometriosis, adenomyosis, or infertility | Reproductive health needs, workplace flexibility, sick leave | Impact on work ability, career progression, support needs |

| (Izadi et al., 2024) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | 733 female healthcare workers (Iran) | Chemical, ergonomic, shift work | Reproductive outcomes, breastfeeding |

| (Jou et al., 2016) | Quantitative (survey) | 700 US women (postpartum) | Paid/unpaid maternity leave | Health insurance coverage, turnover |

| (Kim & Parish, 2020) | Quantitative (survey) | 3405 Korean working women | Family-supportive policies, benefits | Fertility intentions (by parity) |

| (Lwin et al., 2024) | Quantitative (survey) | 557 US surgeons | Workplace support during pregnancy | Burnout, career satisfaction |

| (Maeda et al., 2022) | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey) | 721 Japanese women (25–44, employed, fertility care) | Job stress, working hours, time off, partner support | Fertility-related quality of life |

| (Metcalfe et al., 2011) | Quantitative (survey) | 836 Canadian women (postpartum) | Parental leave, workplace support | Timing of first pregnancy |

| (Mínguez-Alarcón et al., 2017) | Quantitative (prospective cohort, survey) | 473/313 women at a fertility center | Physically demanding work, shift work | Ovarian reserve, oocyte yield |

| (Mirick & Wladkowski, 2022) | Qualitative (interviews) | 328 women doctoral students | Infertility, pregnancy loss, institutional support | Productivity, support needs |

| (Moćkun-Pietrzak et al., 2022) | Quantitative (survey) | 520 midwives (Poland) | Shift work, night shifts | Infertility, miscarriage, sexual health |

| (Payne et al., 2018) | Quantitative (online survey) | 563 UK employees (fertility treatment) | Work–treatment conflict, policy | Absence, career impact, distress |

| (Ponzo et al., 2022) | Quantitative (survey) | 1867 US employees (Flo app users) | Menstrual symptoms, workplace support | Productivity, absenteeism |

| (Rangel et al., 2022) | Quantitative (survey) | 671 US surgeons (likely female) | Workplace support for clinical work reduction during pregnancy | Major pregnancy complications, workplace support |

| (Sabbath et al., 2024) | Quantitative (cohort) | 3110 women (21–45, US/Canada) | Job control, independence, decision-making | Fecundability (time to pregnancy) |

| (Shreffler, 2016) | Quantitative (survey) | 1800 US women (employed) | Professional job characteristics | Fertility intentions, behaviors |

| (Silverberg et al., 2009) | Mixed methods (case study, survey) | Employees of Southwest Airlines, 605 employers | Infertility coverage, managed care | Resource use, morale, retention |

| (Stanley & Foti, 2020) | Qualitative (interviews) | 66 individuals, 8 experts | Employer insurance, state mandates | Access to infertility services |

| (Steyn et al., 2022) | Quantitative (survey) | 1557 UK employees | Fertility journey, workplace support | Wellbeing, job satisfaction, absence |

| (Steyn et al., 2024) | Quantitative (survey) | 1031 UK employees | Fertility support, workplace policies | Fertility challenges, productivity, retention |

| (Wan & Chung, 2011) | Quantitative (survey) | 200 nurses (Taiwan) | Shift work, unit type | Ovarian cycle pattern |

| (Wang & Tan, 2024) | Quantitative (longitudinal) | Dual-earner UK couples | Flexible work arrangements | Fertility (first birth probability) |

| Thematic Domain | Studies | Key Workplace Factors | Reported Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shift Work and Circadian Disruption | (Izadi et al., 2024; Mínguez-Alarcón et al., 2017; Moćkun-Pietrzak et al., 2022; Wan & Chung, 2011) | Night shifts, rotating schedules, chemical and ergonomic exposures, physically demanding work | Infertility, miscarriage, reduced ovarian reserve, disrupted ovarian cycles, adverse reproductive outcomes |

| Organizational Stress and Burnout | (Armijo et al., 2021; Barzilai-Pesach et al., 2006; Győrffy et al., 2014) | Job stress, heavy workload, training demands, burnout, lack of breastfeeding support | Reproductive disorders, negative fertility treatment outcomes, barriers to childbearing, burnout |

| Workplace Flexibility and Accommodations | (Castillo-Angeles et al., 2022; Fernandez-Pineda et al., 2025; Gilbert et al., 2023; Hvala & Hammarberg, 2025; Maeda et al., 2022; Mirick & Wladkowski, 2022; Ponzo et al., 2022) | Working hours, workload reduction during pregnancy, sick leave, accommodations for reproductive health, workplace stigma | Fertility-related quality of life, postpartum depression, emotional distress, absenteeism, productivity loss, career impact |

| Fertility-Related Policies and Organizational Support | (Anderson & Goldman, 2020; De Oliveira Trigo et al., 2023; Herweck et al., 2025; Jou et al., 2016; Kim & Parish, 2020; Lwin et al., 2024; Metcalfe et al., 2011; Rangel et al., 2022; Sabbath et al., 2024; Shreffler, 2016; Silverberg et al., 2009; Stanley & Foti, 2020; Steyn et al., 2022, 2024; Wang & Tan, 2024) | Paid/unpaid maternity leave, fertility benefits, family-supportive policies, flexible work arrangements, employer insurance, stigma policies | Fertility intentions, access to services, employee retention, morale, job satisfaction, well-being, fecundability, pregnancy complications, productivity, and career outcomes |

| Study | Economic/Productivity Indicator(s) | Reported Findings | Context/Sector |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Castillo-Angeles et al., 2022) | Income loss during the postpartum period | Reported reductions in income and professional activity after childbirth, associated with limited workplace flexibility | Female surgeons, USA |

| (De Oliveira Trigo et al., 2023) | Career progression, anxiety, disclosure | Fertility-friendly workplace policies are associated with improved career satisfaction and reduced anxiety | Mixed workforce and employers, Portugal |

| (Fernandez-Pineda et al., 2025) | Work performance post-miscarriage | Emotional distress and reduced work performance reported; limited organizational support exacerbated absenteeism | Employed women, Spain |

| (Hvala & Hammarberg, 2025) | Work ability and career impact | Endometriosis and infertility associated with perceived reduction in work ability and hindered career progression | Employed women, Australia |

| (Jou et al., 2016) | Turnover, insurance coverage | Paid maternity leave correlated with higher retention and continuation of health insurance | US employees (postpartum) |

| (Ponzo et al., 2022) | Absenteeism, productivity | Menstrual symptoms associated with increased absenteeism and productivity loss | App-based working women, UK/US |

| (Silverberg et al., 2009) | Morale, retention, resource use | Implementation of infertility coverage improved morale and retention; reduced turnover | Airline employees, USA |

| (Steyn et al., 2022, 2024) | Productivity loss, retention, job satisfaction | Fertility support policies correlated with higher job satisfaction and retention; about one-third reported decreased productivity due to fertility treatments | UK employees, cross-sectoral |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Virgillito, D.; Ledda, C. The Impact of Organizational Dysfunction on Employees’ Fertility and Economic Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110416

Virgillito D, Ledda C. The Impact of Organizational Dysfunction on Employees’ Fertility and Economic Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(11):416. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110416

Chicago/Turabian StyleVirgillito, Daniele, and Caterina Ledda. 2025. "The Impact of Organizational Dysfunction on Employees’ Fertility and Economic Outcomes: A Scoping Review" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 11: 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110416

APA StyleVirgillito, D., & Ledda, C. (2025). The Impact of Organizational Dysfunction on Employees’ Fertility and Economic Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Administrative Sciences, 15(11), 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110416