Drivers toward Social Entrepreneurs Engagement in Poland: An Institutional Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Entrepreneurship Field

2.2. Factors Influencing the Involvement in Social Enterprises

2.3. Theoretical Framework

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Research Methods and Techniques

- Individual in-depth interviews conducted among 32 interviewees (including 22 social entrepreneurs (founding member) and 10 stakeholders—representatives of the immediate environment, i.e., public administration, social economy support centres, loan and guarantee organisations);

- On-site observations conducted in social enterprises;

- Analysis of documents and materials concerning the interviewed social enterprises.

3.2. Sample Selection

3.3. Data Analysis Methods

- The triangulation criterion: the use of more than one data source on a given topic.

- The ethical criterion: data protection and care for the well-being of respondents, respect for their views, sensitivity to their situation.

- The communicative criterion: the research process requires dialogue with the individuals, getting to know their lifestyles and behaviours.

- The researcher’s self-awareness and development: ensuring a high level of one’s own awareness and knowledge (keeping a research journal, consulting on current issues with experienced researchers specialising in qualitative research).

- Validation of findings.

4. Empirical Findings and Discussion

4.1. Factors Affecting the Involvement in Social Enterprises

4.1.1. Social or Personal Advantages

4.1.2. Public Support

4.1.3. Norms and Values

4.1.4. Self-Fulfilment

4.1.5. Random Events

4.1.6. Social and Family Models

4.1.7. Beliefs and Ideas

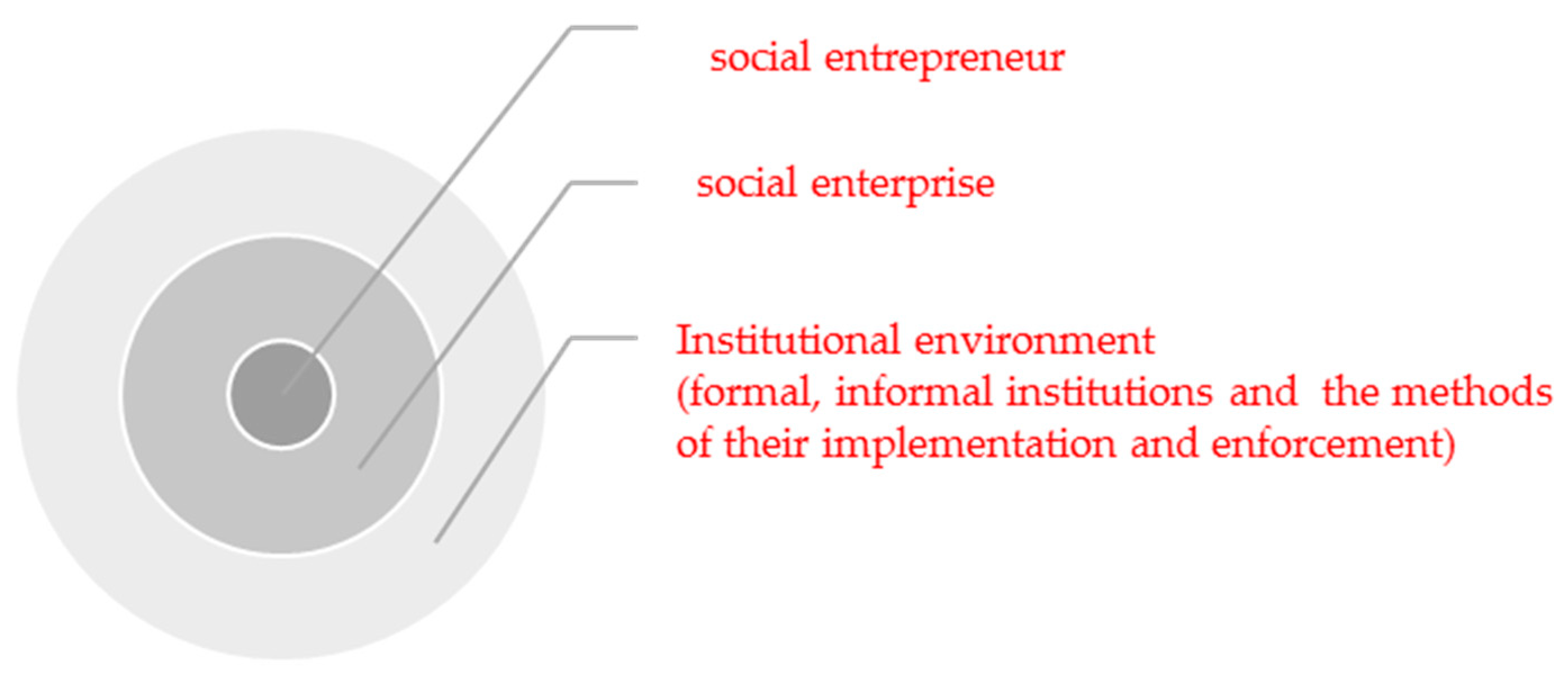

4.2. The Institutional Context of Engagement in Social Entrepreneurship

- “taking responsibility for those who have it uphill all the way” (Se19);

- “concern for man in the name of solidarity values, responsibility for one another” (Se11).

“Because it was possible to obtain a grant to set up a business. If the same grant could be obtained with a different legal form, we would have no reason to set up this complex organisational structure. We have already had one organisation. Many social enterprises were established in this way because of the the available grants”.(Se4)

- “Grant considerations only determined the choice of this form of operation. [...] We knew what we wanted to do and how we wanted to do it, for us it was only a form of achieving our goals”. (Se7)

- “Many of our beneficiaries had no intention to become social entrepreneurs. These business plans were specifically created in order to obtain EU funding”. (S6)

“If the cooperative members [...] obtained a grant and know that all they have to do is not fail for a year and spend money on what they have planned, then, in fact, many of these cooperatives were set up according to the principle ‘let’s try and see if we succeed’ […]”.(S3)

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Social Enterprises Profiles and Sample Characteristics

| Social Enterprise (Se) | Legal Form | Year of Foundation | Founder Type | Scope of Social Activity | Scope of Business Activity |

| Se1 | Social cooperative | 2005 | Natural person | Professional and social activation of people with disabilities | Services: IT and training |

| Se2 | Association | 2009 | Natural person | Local development, promotion of tourism, development of entrepreneurship among inhabitants | Promotion and sale of local products, tourist information |

| Se3 | Social cooperative | 2012 | Natural person | Employment, community service activities | Services: advertising, printing, sewing, training |

| Se4 | Social cooperative | 2014 | Legal person | Professional activation of women from rural areas, integration of parents adopting children, development of local community | Services: caring for children, old people |

| Se5 | Non-profit company | 2007 | Legal person | Professional and social activation of people with disabilities | Services: catering and restaurant; rental of training rooms |

| Se6 | Social cooperative | 2014 | Natural person | Professional and social activation of excluded groups | Services and facilities: catering and restaurant |

| Se7 | Social cooperative | 2011 | Natural person | Professional and social activation of excluded groups | Services: advertising, online promotion, PR |

| Se8 | Foundation | 2017 | Natural person | Professional activation of excluded persons | Restaurant services |

| Se9 | Social cooperative | 2007 | Natural person | Professional activation of excluded persons | Services: café, cleaning services |

| Se10 | Social cooperative | 2011 | Natural person, legal person | Professional and social activation of people with disabilities; promotion of the art of people with disabilities | Services: craftwork |

| Se11 | Foundation | 1989 | Natural persons | Professional and social activation of excluded groups (homeless people, immigrants) | Agricultural holding |

| Se12 | Social cooperative | 2012 | Natural person | Professional activation of the unemployed | Services: childcare (nursery, kindergarten) |

| Se13 | social cooperative | 2007 | Natural person | Professional activation of excluded persons | Services: cleaning and maintenance of green areas |

| Se14 | Social cooperative | 2009 | Community, NGO | Professional activation of excluded persons, development of local community | Services: food and beverage, training |

| Se15 | Foundation | 2007 | Legal person, NGO | Activation of the unemployed and persons threatened by social exclusion through work and education | Services and facilities: carpentry, catering, laundry, training; Production: woodworking products |

| Se16 | Social cooperative | 2011 | Legal person, NGO | Professional and social activation of excluded people (substance addicts) | Services: repair, cleaning, construction, care and support services |

| Se17 | Social cooperative | 2013 | Natural person | Professional and social activation of people with disabilities | Services: maintenance of green areas |

| Se18 | Social cooperative | 2015 | Natural person | Professional and social activation of the unemployed | Services: maintenance of green areas |

| Se19 | Non-profit company | 2013 | Legal person, NGO | Promotion of culture, art, integration of the academic community | Food and beverage services |

| Se20 | Foundation | 1990 | Natural person | Activation and reintegration of adults with disabilities | Services: organisation of cultural events |

| Se21 | Foundation | 2015 | Legal person | Social and professional rehabilitation of people with disabilities | Craftwork |

| Se22 | Labour cooperatives | 2014 | Natural person | Promotion of social activity | Services: consulting and advisory services |

| Source: Own study. | |||||

Appendix B. Stakeholders’ Profiles and Sample Characteristics

| Stakeholder (S) | Represented Organisation/Sector | Scope of the Organisation’s Activity | Interviewee Function in the Organisation |

| S1 | Public administration, regional level/Public | Coordination of social economy policies in the region | CEO |

| S2 | Public administration, regional level/Public | Research and analytical activities, including those related to SE, cooperation with social economy support centres | CEO |

| S3 | Loan and guarantee organisation/Social | Financial services (advisory services, loans, guarantees) for the social and private sectors | CEO |

| S4 | Social economy support centre/Social | Consultancy, training, information, incubation of ES entities | CEO |

| S5 | Public administration, regional level/Public | Coordination of social economy policy in the region; running a social economy support centre (including counselling, grants for cooperatives) | Consultant, expert, researcher on SE |

| S6 | Social economy support centre/Social | Supporting social enterprises and other social economy entities through consultancy, training workshops, information and incubation | Manager |

| S7 | Municipal/Public Office | Supervision and coordination of the municipality’s activities (including social issues) | CEO |

| S8 | Union of labour cooperatives/Private | Support for individuals and organisations interested in creating and developing cooperative activities (consulting, financial support, ocean of cooperative activities) | CEO |

| S9 | Financial sector/Private | Loans and guarantees to the social economy sector, commercial entities and individuals | CEO |

| S10 | Municipal Labour Office/Public | Professional activation of the unemployed; non-refundable grants for the creation of social cooperatives | CEO |

| Source: Own study. | |||

References

- Aidis, Ruta, Saul Estrin, and Tomasz Mickiewicz. 2007. Entrepreneurial Entry: Which Institutions Matter? IZA Discussion Papers, No. 4123. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/35677/1/599380896.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2019).

- Austin, James, Jane Wei-Skillern, and Howard Stevenson. 2006. Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both? Rochester. Scholarly Paper. New York: Social Science Research Network. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1501555 (accessed on 13 July 2019).

- Bacq, Sophie, and Frank Janssen. 2011. The multiple face of social entrepreneurship: A review of definitional issues based on geographical and thematic criteria. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 23: 373–403. [Google Scholar]

- Bogacz-Wojtanowska, Ewa, Izabela Przybysz, and Małgorzata Lendzion. 2014. Sukces i Trwałość Ekonomii Społecznej w Warunkach Polskich. Warszawa: Fundacja Instytut Spraw Publicznych. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, Jonathan. 1972. Taxonomy of social need. In Problems and Progress in Medical Care: Essays on Current Research, 7th ed. Edited by Gordon McLachlan. London: Oxford University Press, pp. 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, Debbi, and Marina Kim. 2011. Social Entrepreneurship Education Resource Handbook. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1872088 (accessed on 13 April 2019).

- Brooks, Arthur C. 2009. Social Entrepreneurship. A Modern Approach to Social Value Creation. New Yersey: Pearsons Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Brouard, François, and Sophie Larivet. 2010. Essay of Clarification and Definitions of related concepts of Social Enterprise. Social Entrepreneur and Social Entrepreneurship. In Handbook of Research on Social Entrepreneurship. Edited by Alain Fayolle and Harry Matlay. Northhampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 29–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chell, Elizabeth, Katerina Nicolopoulou, and Mine Karataş-Özkan. 2010. Social entrepreneurship and enterprise: International and innovation perspectives. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 22: 485–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ciepielewska-Kowalik, Anna, Bartosz Pieliński, Marzena Starnawska, and Aleksandra Szymańska. 2015. Social Enterprise in Poland: Institutional and Historical Context. ICSEM Working Papers, No 11, The International Comparative Social Enterprise Models, Liege, Belgium. Available online: https://www.iap-socent.be/sites/default/files/Poland%20-%20Ciepielewska-Kowalik%20et%20al.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2019).

- Creswell, John W. 2013. Projektowanie Badań Naukowych. Metody Jakościowe, Ilościowe i Mieszane. Wydanie 1. Kraków: Uwydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Dacin, Peter A., Tina Dacin, and Margaret Matear. 2010. Social Entrepreneurship: Why We Don’t Need a New Theory and How We Move Forward from Here. Academy of Management Perspectives 24: 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Lance E., and Douglas C. North. 1971. Institutional Change and American Economic Growth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dees, Gregory J. 2001. The Meaning of Social Entrepreneurship. Working Paper. Stanford, CA, USA: Stanford University. [Google Scholar]

- Defourny, Jacques. 2001. From Third Sector to Social Enterprise. In The Emergence of Social Enterprise. Edited by Carlo Borzaga and Jacques Defourny. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Defourny, Jacques, and Marte Nyssens. 2010. Conceptions of Social Enterprise and Social Entrepreneurship in Europe and the United States: Convergences and Divergences. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 1: 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembińska, Aleksandra. 2012. Metody jakościowe wobec problematyki przedsiębiorczości. In Przedsiębiorczość. Źródła i Uwarunkowania Psychologiczne. Edited by Zofia Ratajczak. Warszawa: Difin, pp. 214–33. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, Norman K. 1978. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, Norman K., and Yvonna S. Linclon, eds. 2009. Wprowadzenie. Dziedzina i praktyka badań jakościowych. In Metody Badań Jakościowych. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, pp. 19–76. [Google Scholar]

- Desa, Geoffrey, and Sandip Basu. 2013. Optimization or bricolage? Overcoming resource constraints in global social entrepreneurship. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 1: 26–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, Päivi, and Anne Kovalainen. 2008. Qualitative Methods in Business Research. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Estrin, Saul, Tomasz Mickiewicz, and Ute Stephan. 2013. Entrepreneurship Social Capital, and Institutions: Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship across Nations. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 37: 479–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2015. A Map of Social Enterprises and Their Eco-Systems in Europe. Synthesis Report. A Report Submitted by ICF Consulting Services, European Commission Directorate General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion. Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2016. Social Enterprises and Their Eco-Systems: A European Mapping Report. Updated Country Report: Poland, European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion. Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri, Elisabeth. 2014. Social Entrepreneurship and Institutional Context: A Quantitative Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, International Doctorate in Entrepreneurship and Management, The Autonomous University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. Available online: https://ddd.uab.cat/record/129035 (accessed on 14 April 2019).

- Flick, Uwe. 2011. Jakość w Badaniach Jakościowych. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Florczak, Ewelina. 2016. Działalność przedsiębiorstw społecznych w Polsce. In Uwarunkowania Działalności Przedsiębiorstw Społecznych w Polsce. Edited by Jacek Brdulak and Ewelina Florczak. Warszawa: Oficyna Wydawnicza Uczelni Łazarskiego, pp. 84–148. [Google Scholar]

- Furubotn, Eirik G., and Rudolf Richter. 2005. Institutions and Economic Theory. The Contribution of the New Institutional Economics. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, Tanvi, and Rishav Raina. 2018. Social entrepreneurship: The need, relevance, facets and constraints. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germak, Andrew J., and Jeffrey A. Robinson. 2014. Exploring the Motivation of Nascent Social Entrepreneurs. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 5: 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados, Maria L., Vlatka Hlupic, Elayne Coakes, and Souad Mohamed. 2011. Social enterprise and social entrepreneurship research and theory: A bibliometric analysis from 1991 to 2010. Social Enterprise Journal 7: 198–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gras, David M., Todd W. Moss, and G. Thomas Lumpkin. 2014. The use of secondary data in social entrepreneurship research: Assessing the field and identifying future opportunities. In Social Entrepreneurship and Research Methods. Research Methodology in Strategy and Management. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd., vol. 9, pp. 49–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gruszewska, Ewa. 2017. Instytucje formalne i nieformalne. Skutki antynomii. Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu. Instytucje w Teorii i Praktyce 493: 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Haugh, Helen. 2005. A research agenda for social entrepreneurship. Social Enterprise Journal 1: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugh, Helen. 2006. Social Enterprise: Beyond Economic Outcomes and Individual Returns. In Social Entrepreneurship. Edited by Johana Mair, Jeffrey Robinson and Kai Hockerts. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar]

- Hausner, Jerzy. 2008. Zarządzanie Publiczne. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- Helmke, Gretchen, and Steven Levitsky. 2004. Informal Institutions and Comparative Politics: A Research Agend. Perspectives on Politics 2: 725–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, Jan. 2008. Pole przedsiębiorczości społecznej w Polsce. In Ekonomia Społeczna w Polsce: Osiągnięcia, Bariery Rozwoju i Potencjał w Świetle Wyników. Edited by Jerzy Hausner and Anna Giza-Poleszczuk. Warszawa: Fundacja Inicjatyw Społeczno-Ekonomicznych, pp. 41–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogendoorn, Brigitte, and Chantal Hartog. 2011. Prevalence and Determinants of Social Entrepreneurship at the Macro-Level. EIM Research Reports. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6480306.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2019).

- Hoogendoorn, Brigitte, Enrico Pennings, and Roy Thurik. 2010. What do we know about social entrepreneurship? An analysis of empirical research. International Review of Entrepreneurship 8: 71–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hota, Pradeep Kumar, Balaji Subramanian, and Gopalakrishnan Narayanamurthy. 2019. Mapping the Intellectual Structure of Social Entrepreneurship Research: A Citation/Co-citation Analysis. Journal of Business Ethics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilinskaya-Pandey, Mariya, and Jeremy Wade. 2019. Social Entrepreneur Quotient: An International Perspective on Social Entrepreneur Personalities. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 10: 265–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerlin, Janelle A. 2012. Defining Social Enterprise across Different Contexts: A Conceptual Framework Based on Institutional Factors. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 42: 84–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerlin, Janelle A. 2017. Shaping Social Enterprise: Understanding Institutional Context and Influence. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Kickul, Jill, and Thomas S. Lyons. 2012. Understanding Social Entrepreneurship: The Relentless Pursuit of Mission in an Ever Changing World. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kopyciński, Piotr. 2018. City Lab as a Platform for Implementing Urban Innovation: The Role of Companies. In International Entrepreneurship as the Bridge between International Economics and International Business: Conference Proceedings of the 9th ENTRE Conference and 5th AIB-CEE Conference. Edited by Krzysztof Wach and Marek Maciejewski. Cracow: Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny w Krakowie, pp. 257–74. [Google Scholar]

- Korunka, Christian, Hermann Frank, Manfred Lueger, and Josef Mugler. 2003. The Entrepreneurial Personality in the Context of Resources, Environment, and the Startup Process—A Configurational Approach. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 28: 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korycki, Arkadiusz. 2015. Partnerstwo na rzecz instytucjonalizacji gospodarki społecznej. Partnerstwo na rzecz instytucjonalizacji gospodarki społecznej. Wywiad z Jerzym Hausnerem, Jerzym Wilkinem, Witoldem Kwaśnickim. Rozmowa z Jerzym Wilkinem. Społeczeństwo Obywatelskie. Badania. Praktyka. Polityka 2: 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kurleto, Małgorzata. 2016. Model Przedsiębiorstwa Społecznego. Warszawa: Difin. [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater, Charles. 1997. The Rise of the Social Entrepreneurship. London: Demos. [Google Scholar]

- Leś, Ewa. 2013. Organizacje Non Profit w Nowej Polityce Społecznej w Polsce na tle Europejskim. Warszawa: Oficyna Wydawnicza ASPRA-JR. [Google Scholar]

- Lukes, Martin, and Ute Stephan. 2012. Entrepreneurs and leaders of non-profit organizations: Similar people with different motivations. Ceskoslovenska Psychologie 56: 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin, G. Thomas, Todd W. Moss, David M. Gras, Shoko Kato, and Alejandro S. Amezcua. 2013. Entrepreneurial processes in social contexts: How are they different, if at all? Small Business Economics 40: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, Johanna, and Ignasi Martí. 2004. Social Entrepreneurship: What are We Talking about? A Framework for Future Research. Working Paper No 546. Barcelona, Spain: IESE Business School, University of Navarra. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, Johanna, and Ignasi Martí. 2006. Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business 41: 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małecka-Łyszczek, Magdalena. 2017. Współpraca Administracji Publicznej z Podmiotami Ekonomii Społecznej. Aspekty Prawnoadministracyjne. Warszawa: Wolters Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Toyah L., Matthew G. Grimes, Jeffery S. McMullen, and Timothy J. Vogus. 2012. Venturing for Others with Heard and Head: How Compassion Encourages Social Entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Review 37: 616–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Labor and Social Policy. 2014. Krajowy Program Rozwoju Ekonomii Społecznej (National Social Economy Development Program). Monitor Polski, No. 811. Warszawa: Ministry of Labor and Social Policy, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Nga, Joyce Koe Hwee, and Gomathi Shamuganathan. 2010. The Influence of Personality Traits and Demographic Factors on Social Entrepreneurship Start up Intentions. Journal of Business Ethics 95: 259–82. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, Alex. 2006. Social Entrepreneurship. New Models of Sustainable Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, Alex. 2010. The Legitimacy of Social Entrepreneurship: Reflexive Isomorphism in a Pre-Paradigmatic Field. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34: 611–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, Douglas C. 1991. Institutions. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 5: 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, Douglas C. 1994. Economic Performance through Time. The American Economic Review 84: 359–68. [Google Scholar]

- North, Douglas C. 2005. Understanding the Process of Economic Change. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- North, Douglas C. 2017. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance, 29th ed. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pacut, Agnieszka. 2018a. Trajektoria zmian przedsiębiorczości społecznej w Polsce. Ekonomia Społeczna 2: 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacut, Agnieszka. 2018b. Social Entrepreneurship in Opinion of Company Leaders and Representatives of Stakeholders. Harvard Dataverse Database. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, Michael Q. 2015. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Perrini, Franceso. 2006. The New Social Entrepreneurship. What Awaits Social Entrepreneurial Ventures? Cheltenham and Northhampton: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Perrini, Franceso, and Clodia Vurro. 2006. Social Entrepreneurship: Innovation and social change across theory and practice. In Social Entrepreneurship. Edited by Johanna Mair, Jeffrey Robinson and Kai Hockerts. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar]

- Perrini, Franceso, Clodia Vurro, and Laura Costanzo. 2010. A process-based view of social entrepreneurship: From opportunity identification to scaling-up social change in the case of San Patrignano. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 22: 515–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pestoff, Victor, and Lars Hulgård. 2015. Participatory Governance in Social Enterprise. 5th EMES International Conference on Social Enterprise, Helsinki. Available online: http://emes.net/content/uploads/publications/participatory-governance-in-social-enterprise/ESCP-5EMES-40_Participatory_Governance_Social_Enterprise.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2019).

- Robinson, Jeffrey. 2006. Navigating Social and Institutional Barriers to Markets: How Social Entrepreneurs Identify and Evaluate Opportunities. In Social Entrepreneurship. Edited by Johanna Mair, Jeffrey Robinson and Kai Hockerts. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 95–120. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrik, Dani. 2011. Jedna Ekonomia, Wiele Recept. Globalizacja, Instytucje i Wzrost Gospodarczy. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Krytyki Politycznej. [Google Scholar]

- Romani-Dias, Marcello, Edson Sadao Iizuka, Elisa Rodrigues Alves Larroudé, and Aline Dos Santos Barbosa. 2018. Mapping of Academic Production on Social Enterprises: An international analysis for the growth of this field. International Review of Social Research 8: 156–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruskin, Jennifer, and Cynthia M. Webster. 2011. Creating Value for Others: An Exploration of social Entrepreneurs’ Motives, ANZAM 2011. Available online: www.anzam.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf-manager/463_ANZAM2011-125.PDF (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Sahasranamam, Sreevas, and M. K. Nandakumar. 2020. Individual capital and social entrepreneurship: Role of formal institutions. Journal of Business Research 107: 104–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassmannshausen, Sean Patrick, and Christine Volkmann. 2016. The Scientometrics of Social Entrepreneurship and Its Establishment as an Academic Field. Journal of Small Business Management 56: 251–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelos, Christian, and Johanna Mair. 2004. Social Entrepreneurship: The Contribution of Individual Entrepreneurs to Sustainable Development. Working Paper 553. Barcelona, Spain: University of Navarra. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekliuckiene, Jurgita, and Eimantas Kisielius. 2015. Development of social entrepreneurship initiatives: A theoretical Framework. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 213: 1015–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharir, Moshe, and Miri Lerner. 2006. Gauging the success of social ventures initiated by individual social entrepreneurs. Journal of World Business 41: 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Venus. 2015. Identifying Constraints in Social Entrepreneurship Ecosystem of India: A Developing Country Context. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2729720 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Shaw, Eleanor, and Sara Carter. 2007. Social entrepreneurship theoretical antecedents and empirical analysis of entrepreneurial processes and outcomes. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 14: 418–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, Jeremy, Todd W. Moss, and G. Thomas Lumpkin. 2009. Research in Social Entrepreneurship: Past Contributions and Future Opportunities. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 3: 161–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, William, and Emily Darko. 2014. Social Enterprise: Constraints and Opportunities—Evidence from Vietnam and Kenya. London: Oerseas Development Institute. Available online: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/8877.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Stake, Robert E. 2009. Jakościowe studium przypadku. In Metody Badań Jakościowych. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonne S. Lincoln. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, pp. 623–54. [Google Scholar]

- Starnawska, Marzena. 2014. Zachowanie poprzez sieciowanie w przedsiębiorczości społecznej w odpowiedzi na trudne otoczenie instytucjonalne—przypadek pięciu spółdzielni socjalnych. Problemy Zarządzania 12: 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, Ute, and Andreana Drencheva. 2017. The person in social entrepreneurship: A systematic review of research on the social entrepreneurial personality. In The Wiley Handbook of Entrepreneurship. Edited by Gorkan Ahmetoglu, Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, Bailey Klinger and Tessa Karcisky. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 205–29. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, Ute, Lorraine M. Uhlaner, and Christopher Stride. 2015. Institutions and social entrepreneurship: The role of institutional voids, Institutional Support and Institutional Configurations. Journal of International Business Studies 46: 308–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronkowski, Piotr, Magdalena Andrzejewska, Klaudia Łubian, Karolina Cyran-Juraszek, and Anna Matejczuk. 2013. Badanie Ewaluacyjne pt. Ocena Wsparcia w Obszarze Ekonomii Społecznej Udzielonego ze Środków EFS w Ramach PO KL; Coffey International Development. Warszawa: Ministerstwo Infrastruktury i Rozwoju. Available online: www.efs.2007-2013.gov.pl/analizyraportypodsumowania/documents/raport_koncowy_ewaluacja_es.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Sullivan Mort, Gillian, Jay Weerawardena, and Kashonia Carnegie. 2003. Social entrepreneurship: Towards conceptualisation. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 8: 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, Albert Chu-Ying, and Wee-Boon Tan. 2013. Developing a Model of Social Entrepreneurship: A Grounded Study Approach. EMES-SOCENT Conference Selected Papers, No. LG13-36. Liege: 4th EMES International Research Conference on Social Enterprise. Available online: https://emes.net/content/uploads/publications/teo___tan_ecsp-lg13-36.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2019).

- Urbano, David, Nuria Toledano, and Domingo R. Soriano. 2010. Analyzing social entrepreneurship from an institutional perspective: Evidence from Spain. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 1: 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, David, Elisabeth Ferri, Marta Peris-Ortiz, and Sebastian Aparicio. 2017. Social entrepreneurship and institutional factors: A literature review. International Studies in Entrepreneurship 36: 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Varga, Eva, and Malcolm Hayday. 2016. A Recipe Book for Social Finance—A Practical Guide on Designing and Implementing Initiatives to Develop Social Finance Instruments and Markets. Luxembourg: European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion. [Google Scholar]

- Weerawardena, Jey, and Gillian Sullivan Mort. 2006. Investigating social entrepreneurship: A multi-dimensional model. Journal of World Business 41: 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkin, Jerzy. 2016. Instytucjonalne i Kulturowe Podstawy Gospodarowania. Humanistyczna Perspektywa Ekonomii. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- Wolk, Andrew. 2008. Advancing Social Entrepreneurship: Recommendations for Policy Makers and Government Agencies; Root Cause. Washington: The Aspen Institute. Available online: https://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/advancing-social-entrepreneurship-recommendations-policy-makers-government-agencies (accessed on 15 April 2019).

- Wronka, Martyna. 2009. Identification of critical success factors of social enterprises—Research results. Management 13: 112–28. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Robert K. 2009. Case Study Research. Design and Methods, 4th ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Robert K. 2015. Studium Przypadku w Badaniach Naukowych. Projektowanie Metody. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Yitshaki, Ronit, and Fredric Kropp. 2015. Motivations and opportunity recognition of social entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management 54: 546–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Subject | Social Enterprise | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research strategy | Case study | |||

| Data collection methods | In-depth interviews | Observation | Secondary data | |

| Data sources | Social entrepreneurs | Stakeholders | Social enterprises | Social enterprises |

| Quality assurance criteria | Triangulation | |||

| Ethical | ||||

| Communicative | ||||

| Researcher’s self-awareness and development | ||||

| Validation of findings | ||||

| Social and personal advantages |

| “We would like to achieve a better, people-oriented tourism development of our region. [...] one that will take advantage of the local potential—people, landscape, history [...] This is our main goal: to develop a customer-friendly tourism in line with world trends, […] without forcing the visitors to do strange things or lying to them”. (Se2) “I do it, I mean, I run a cooperative so that I don’t drink alcohol, because I’m terminally ill for the rest of my life. [...] I do it mainly for myself, not drinking, but also for others, to help them. It’s an element of my therapy and my life strategy”. (Se16) “We were just long-term unemployed with problems; we wanted to get ourselves a job. And it was a problem for a long time for various reasons—our dependence, lack of offer on the market. (…). We were then using social services in the city. Social Services sent us to a Social Integration Centre, where we trained up and six of us decided to open a social cooperative”. (Se13) |

| Public support |

| “I would like to emphasise the role of EU funds or public funds in general. For us, they were the stimulus that enabled us to take new action. Thanks to them, we established a non-profit company and later a social cooperative, which I think of as the development of our statutory activity. This allowed us to expand the scale of professional activation of people with disabilities and improve the quality of our market offer. It would have been difficult to achieve these goals without external funding”. (Se5) |

| Norms and values |

| “Our main goal is to raise the man who is most abandoned and somehow excluded; to raise him to a level where he becomes independent, useful, where he regains a sense of value and dignity. [...] We believe that in every human being, somewhere deep down, there is a potential that simply needs to be extracted. At the centre of our values has always been care for people, such solidarity values, responsibility for each other”. (Se11) “[…] What motivated us to create a social enterprise was, first of all, the readiness to help. […], the need to do something together, [...] the sense that it is fun to do something together, [...] that we feel good about each other, that we like each other, that we like to be together, that we want to be together, that we not only want to work with each other, but that we want to spend time together. [...] And somewhere in us, in the group of people who started this activity a few years ago, there was such a strong belief in the value of common action”. (Se15) |

| Self-fulfilment |

| “I wanted to do something sensible in my life; it means something good to make it really beneficial for people other than me and my family. And if it is possible to combine it with earning money, let’s say it’s possible to live one way or another, although it’s not heaps of money, but it’s possible to function as if it’s enough [...] it’s hard for me to imagine myself, for example, in some company, where it’s just about making money”. (Se11) “We do not put pressure on ourselves or our employees or subcontractors here. We do not negotiate totally hard-core terms of cooperation and so on. [...] We are the decision-makers, we have influence, we are not employees, [...] and someone only manages us. We have a responsibility, we are responsible for everything”. (Se3) |

| Random events |

| “The setting-up of the organisation coincided with my personal situation, my situation in life. I adopted a child and started to socialise in these circles. I got in touch with people who were dedicated to the mission of saving children. They have often experienced unemployment and they had to earn a living for these children by themselves, what the state provides for care is not enough, they have to work anyway, and on the other hand they were unemployed. [...] We have put all this together so that caring for children fits our needs, this region, where we lived in, and so we have formed our organisation”. (Se4) |

| Social and family models |

| “When my parents started the foundation, I was one and a half years old [...] now my parents are seventy. We have to continue their mission. I have been watching this activity since childhood, I have grown up in it, it is natural for me; it is something that gives meaning to my life, and above all, many people need this kind of activity”. (Se11) |

| Beliefs and ideas |

| “I have a mission from God to help these alcohol addicts, but it’s how I help myself and live my life”. (Se16) “[…] We have come up with the idea that running a business may be a form of generating income for the association for its statutory activity. That is, if the social business quote goes well unquote, if the income is good, then the social goal will be met, because the disabled will have jobs, and there will be additional funds for our various activities”. (Se5) |

| Specifications | Influencing Factors |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Factors | Institutions | Enforcement of the Institutions |

|---|---|---|

| Social and personal advantages Random events Norms and values Social and family models Self-fulfilment Beliefs and ideas | Informal | Self-control of individuals, informal social control |

| Public support | Formal | Codified rules laid down in documents by public decision-makers |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pacut, A. Drivers toward Social Entrepreneurs Engagement in Poland: An Institutional Approach. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10010005

Pacut A. Drivers toward Social Entrepreneurs Engagement in Poland: An Institutional Approach. Administrative Sciences. 2020; 10(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10010005

Chicago/Turabian StylePacut, Agnieszka. 2020. "Drivers toward Social Entrepreneurs Engagement in Poland: An Institutional Approach" Administrative Sciences 10, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10010005

APA StylePacut, A. (2020). Drivers toward Social Entrepreneurs Engagement in Poland: An Institutional Approach. Administrative Sciences, 10(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10010005