Abstract

The aim of this article is to explore key changes in the mode of operation of Polish social economy organizations (SEOs) that result from a social policy targeted at strengthening their independence and sustainability. The activities of SEOs are largely supported by public institutions, but their opportunities for assistance of capacity building are considered insufficient. Owing to the current policy, not only an economic independence, but also the structure and behavior of supported social organizations, especially in their relations with other stakeholders, can be strengthened. Based on the exploratory analysis on how SOEs change their independence and sustainability as a result of implementation of the public policy, a conceptual model of value co-creation will be used. The model enables analyzing the scope and scale of stakeholder engagement in the development of SEOs. The empirical research was conducted using a survey among 112 Polish social economy organizations. The results of the study show that the market-oriented approach not only reduces the scale of relations between SEOs and their stakeholders but also affects the way SEOs work, transforming them to be more like traditional businesses.

1. Introduction

Within of 30 years of transformations, Poland, as one of the Central and Eastern European countries, has been struggling to create a stable model of social economy. Here, the problems facing post-communist countries have become evident. Analyses of solutions used in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe demonstrate that, despite some differences, these countries have chosen a similar path, and changes in many areas have brought about similar effects (Schwenger et al. 2013). The social economy organizations in Poland implement their mission-based activities and, at the same time, attempt to carry out business activities aimed at the diversification of income and their development (Vaceková and Svidroňová 2014). As a result, these organizations neither constitute a fully fledged institution pursuing social goals nor are a full market player (Pacut 2010). Due to the policy focused on development, independence and stabilization of activities of social economy organizations government activities play an important role in this context (Vaceková and Svidroňová 2014; Wells 2001). In addition, at the same time, the approach to perceiving and supporting innovation is changing towards a social one - the importance of cooperation with a wide spectrum of actors (including social economy entities) and the active participation of future users in creating solutions that meet their expectations are emphasized (see more; Kopyciński 2017). The term “social economy organization” is used in this article to describe the following organizations: the voluntary sector, non-governmental organizations, and non-profit organizations. When it refers to both social economy organizations and social enterprises, the term of “social entity” can be used instead. The main reason for that is the existence of imprecise definitions of these concepts in Polish law and public policies. However, because of the lack of precise definitions, both of these terms will be used interchangeably as synonyms in this article. For instance, according to the legal interpretation of Polish law, a social enterprise is also a non-governmental organization engaged in any type of revenue-generating activities, e.g., selling products and services and allocation of the proceeds to their statutory activities. According to the research carried out in Poland, a social enterprise is defined as an entity pursuing social objectives that introduces products or services to the market, irrespective of profit generation (Hausner et al. 2007; Wygnański and Frączak 2008). In this article, a very broad definition of social enterprise will be used. It also means the use of a broad definition of social economy (Borzaga and Defourny 2004; Pacut 2010; Perrini 2006; Spear et al. 2018).

Therefore, the Polish state supports the developments of the social economy sector, including associations, foundations, or social enterprises. The evolution in this field has become a challenge for the state and SEOs (Farazmand 2018). A key issue concerns the direction of change reflected in the following dilemmas: (1) should the SEOs become more market-oriented and pursue economic goals in order to achieve independence and sustainability that provide their development or (2) should they act in line with social goals and only additionally pursue economic goals?

In European countries, social activities are more and more commercialized (Schwenger et al. 2013). Consistent implementation of policies strengthening the economic independence of NGOs (Mikołajczak 2017) supports their market orientation and products or services commercialization (Nunnenkamp and Öhler 2010). The term “commercialization” will be used to describe the process of changing a SEO’s mode of operation when it becomes more market-oriented. This process is crucial for SEOs’ independence as it can imply a redefinition of the social goals of an organization and, consequently, their replacement by economic objectives (Fudaliński 2014). In Poland, the government implements public policies to stimulate or accelerate this process.

The SEOs conducting business activities are interested in searching for new market opportunities (Defourny 2001; Żur 2014). Those entities also try to change internally, e.g., their structure and their mode of action (Vaceková and Svidroňová 2014). Finally, the relationship with contractors and stakeholders can be revised (Borzillo et al. 2014). The scale and extent of changes in social economy organizations is an important research issue. Therefore, this study is focused on the changes in the way SEOs’ work result from the state-determined policy. These changes increase the entities’ independence and strengthen mission-related activities. However, paradoxically, it also takes them further away from the third sector and turns them into much more market-oriented organizations (Borzaga and Defourny 2004; Mikołajczak 2018). In line with this, an analysis will be provided to assess the relationship between commercialized social economy organizations and their stakeholders, in particular, their customers. To this end, a conceptual and an empirical examination involving stakeholder and co-creation analysis will be conducted.

The research objective of this article is to explore key changes in the mode of operation of Polish social economy organizations that result from a social policy targeted at strengthening their independence and sustainability. The key research aspects include collaboration between the actors involved in the process of value creation and a public policy aimed at the commercialization of SEOs’ goods and services (Fudaliński 2014). The main question of the analysis is what kind of effects can occur due to by the commercialization of SEOs’ activities? The changes resulting from commercialization are not always noticeable. A co-creation model, however, made it possible to spot the changes and describe the phenomenon. The next research question focused on how the relationships between stakeholders in the co-creation process by using a matrix of stakeholders’ participation can be described? Finally, using a co-creation model and a matrix of stakeholders’ participation, how can the effects of SEOs’ commercialization be analyzed? To answer these questions, the study was conducted based on 112 entities in the region of Lesser Poland between 2016 and 2019. For the analysis of the results, a co-creation model and the analysis of stakeholders were applied.

The article is divided into four sections. In Section 1, different issues on social economy organizations and the factors of change are analyzed. This literature review provides an outlook on (1) targets of the state policy aimed at commercializing SEOs, (2) the role of co-creation in social economy organizations and (3) the relationship between SEOs and their stakeholders. For the purpose of this article, stakeholders were selected from the participants in the process of creation and implementation of innovations or in the process of creation of products or services. The methodological section presents a sampling description based on 112 Polish SEOs, data collection methods using surveys and in-depth interviews, and data analysis methods. In the next section, the results of the research are analyzed. It shows how the engagement of stakeholders decreases with the changes in the SEOs mode of operation. Finally, the results are summarized, providing our contribution and recommendations for public policies as well as suggestions on further research.

2. Social Economy Organizations and the Factors of Change: Public Policy, Co-Creation, and Stakeholder Engagement

2.1. State Policy Aimed at Commercializing of Social Economy Organizations

The social economy organizations in Poland carry out mission-related activities that are subject to principles other than economic activity. Mission-related activities are divided into unpaid mission-related activities, when the customer does not pay for the services provided by the entity, and paid mission-related activities, when the customer pays for the service, but this service is not carried out for profit. The SEOs may also operate a business activity. The generated profit must be allocated to implementation of the organization’s mission; otherwise, the profit can be taxed under general accounting principles (Farazmand 2018). In Poland, all SEOs engaged in economic activities or in paid statutory activities are considered by public authorities to be companies (Wygnański and Frączak 2008). It is associated with a very broad approach to social entrepreneurship and, as a consequence, to the social economy sector. According to the Polish definition, it is not necessary to conduct economic activities to be classified as a social enterprise (Hausner and Laurisz 2008). Therefore, supporting this sector is problematic since even a small amount of financial aid is treated as public help. However, the state or local authorities can contract public services (Defourny 2001). The SEOs’ activities are supported by allowing them to broaden a range of activities. At the same time, the SEOs’ activities are dependent on public money (Vincent 2006) and interdependent on the economic functions of the public policy (Moulaert and Nussbaumer 2005). This type of state activity serves to pursue a social policy. As a result, SEOs’ goals become the state objectives concerning the development and implementation of public policies. Using that kind of support leads to the increased dependence of SEOs on the state (Vaceková and Svidroňová 2014). Moreover, organizations that spend their funds exclusively on providing social services do not grow in strength. A withdrawal from public contracting can lead to the end of an SEO’s activity due to insufficient resources (Wells 2001). Organizations carrying on exclusively mission-related activities encounter financial difficulties that have a negative impact on their development, economic stability, and staff retention (Fudaliński 2014; Mikołajczak 2018).

In addition, there is another way to finance SEOs activities. The organizations can themselves create and increase revenues and generate a surplus in order to cover operating costs. Hence, the basic goal of state actions is to reinforce the SEOs’ sustainability and independence, understood as their economic independence (Blackburn 2012; Moulaert and Ailenei 2005). The Polish government and local authorities allocate resources in order to encourage SEOs to launch business activities or to scale up of existing businesses (Hausner et al. 2007; Mikołajczak 2017; Pacut 2010). As a result, the state supports the process of commercializing social economy organizations and thus stimulates an increase of social enterprises created, primarily through a transformation of NGOs implementing social activities into entities partly engaged in economic activity (Perrini 2006). However, business activity does not have to constitute a basis for the operations of these entities (Alter 2007; Amin 2009). An immediate objective of a public policy is an increase in the financial independence of social entities. An intermediate goal is to strengthen social capital by supporting independence and the development of social entities (Laville et al. 2005). Social capital is an important factor when it comes to long-term development of SEOs, societies (Laville and Nyssens 2001), and also economies (Beugelsdijk and Smulders 2009; Helliwell and Putnam 1995; Mikucka and Sarracino 2014). In particular, Central and Eastern European countries, including Poland, are characterized by a noticeably lower level of social capital than Western European countries (Czapiński and Panek 2015). Moreover, from the perspective of socio-economic development, the trends of changes are not optimistic for the region. Given the index of civic cooperation, in Western Europe countries, a positive trend can be observed, and in post-Soviet states, a negative trend can be observed (Sarracino and Mikucka 2017). Therefore, the Polish government implemented a policy to support existing entities and the emergence of new NGOs and new social enterprises (Laurisz and Mazur 2008). This is also a general reason why governments support SEO development (Evers 2001; Spear et al. 2018).

An important issue is the distinction between direct financial support for an entity and the support of its mission-related activity. In Poland, if an SEO implements a project consistent with the mission and financed by public funding, it has to finance a part of this project on its own, even if the SEO performs tasks contracted by the state (Pacut 2010). The government significantly limits the possibility of building material or financial capital in case of SEOs implementing mission-related projects. This can be considered to be a major impediment in the implementation of SEOs’ mission-related activities (Bohdziewicz-Lulewicz and Rychły-Mierzwa 2018). Moreover, entities undergoing commercialization can obtain financial support from the state for building up physical capital, development, and stabilization. In line with this, this study focuses on an examination of entities participating in the MOWES project that was implemented in Poland in order to support the commercialization of social entities. The Malopolska Social Economy Support Centre (Małopolski Ośrodek Wsparcia Ekonomii Społecznej—MOWES) was a publicly financed project implemented in Malopolska in 2016–2019. Malopolska or Lesser Poland Voivodeship is a region in southern Poland. The main aim of this project was to support social economy organizations and social enterprises in order for them to become independent from public transfers and public support. The project also helped to commercialize SEOs’ activities.

2.2. Co-Creation in Social Economy Organizations

From the business perspective, co-creation is a joint action on the creation of value by an enterprise and other stakeholders in order to obtain a better final product. Changes, particularly in information and communications technology, lead to a growing volatility of consumer attitudes with respect to brands and products (Ramaswamy and Gouillart 2010). To create solutions, increasing the quality of products and the loyalty, attachment, and trust of customers, SEOs change the way they think about the customer’s needs and redirect the process of product, services, and innovation development (Mikołajczak 2018). That entails moving beyond the framework of internal creation of solutions and broadly understood co-production toward the engagement of customers in the process of creating, testing, and improving solutions (De Koning et al. 2016; O’Hern and Rindfleisch 2010). Co-creation as a mode of operation of market players is becoming increasingly prevalent. Furthermore, co-creation is of growing importance in organizations from the social economy sector.

Changes, especially in technology and economy, have resulted in a growing instability in the market of goods and services and the relations between customers and producers (Vargo and Lusch 2004). The instability is also visible across other areas and relations (Von Scheel et al. 2015). From that perspective, many researchers emphasize the necessity to change supply–demand relationships toward an interactive model of co-creation (Ramaswamy and Ozcan 2014). As a consequence, a gradual change of the traditional value creation model into a system where customers and suppliers interact and collaborate can be noticed. Many researchers highlight that the process of creating value must be changed from product-oriented to service- or customer-oriented (Prahalad and Ramaswamy 2004; Vargo and Lusch 2004; Vargo et al. 2008). These changes reshape today’s economy into a new system of local and global interrelated businesses. The value is created within a large and broad cooperation where different stakeholders, particularly customers, are involved in the process of value creation (Laville et al. 2005). Thus, it is possible to create a new value or experience for all stakeholders using internal and external sources (Olson et al. 2012). This new approach is called co-creation.

Co-creation is presented here as a new paradigm in management, helping companies and customers to create value through interactions (Galvagno and Dalli 2014). This concept is defined as managing the process of creating value at the customer level (Ramaswamy and Ozcan 2014). It converts the market into a place where dialogue between customers and companies is naturally built (Prahalad and Ramaswamy 2004). In this context, businesses and the state strive to create a forum for debate where individuals, organizations, governments, and economies can cooperate together (O’Hern and Rindfleisch 2010). In line with this, it is necessary to inspire all participants to change their old, traditional mode of operation into broad collaboration, cooperation, and co-creation (Ramaswamy and Ozcan 2014; Ramaswamy and Ozcan 2013).

A generally overlooked, albeit very important, aspect of the co-creation model is its implementation in all activities of social economy organizations (Dahan et al. 2010). Day-to-day business is based on extensive cooperation with stakeholders. The process of creating social innovation is a result of cooperation with customers, public authorities, and other stakeholders (Dahan et al. 2010; Bitzer and Glasbergen 2015). These joint activities create social value (Gouillart 2014; Pinho et al. 2014). That means that activities carried out by social economy organizations should be strongly oriented toward innovation and added value creation (Galvagno and Dalli 2014). A broad cooperation aimed at value creation has been popular in the social economy sector for several years (Nunnenkamp and Öhler 2010). An extensive cooperation with stakeholders is a key feature of SEOs’ mode of operation (Borzillo et al. 2014).

In order to meet the research objective of this article, it is necessary to examine the stages, activities, and forms of engagement of stakeholders in creating goods and services. There are four types of customer co-creation listed in the most popular classifications: (1) collaborating, (2) tinkering, (3) co-designing, and (4) submitting (O’Hern and Rindfleisch 2010). A slightly different way of classification relays on defining the role of a participant in the co-creation process, specifically, using public participation and the citizens–local government relations. Given this approach, we can distinguish three types of citizen involvement—(1) citizen as a co-implementer, (2) citizen as a co-designer, and (3) citizen as an initiator (Voorberg et al. 2015). In order to identify the scope of SEOs’ participation, the second approach will be used here. In the next analytical step, concerning the identification of the scale of involvement, a different method of specifying the phases of co-creation will be applied, as the local government is the stakeholder that most strongly affects SEO behavior. Therefore, the analysis will be carried out using the gradation of social participation or the involvement of organizations in the relations between citizens and the state. The following shortened version of the engagement scale was used: (1) a lack of participation (do not participate), (2) possible participation (allowed to participate), (3) creation of a participation opportunity (encouraged to participate), (4) involvement in the process (engagement in the process), and (5) equal participation. In the future, the results will be used to design a broader study using a different methodology.

The proposed classification of the relationships between SEOs and their stakeholders is based on the relations between citizen and local government, where the citizen is understood as an entity involved in the process of cooperation with the local government (Laville et al. 2005). In this context, the main institutional actor cooperating with SEOs is actually the local government (Table 1). In an attempt to strengthen citizens’ activity and develop social involvement, the authorities tend to use co-creation tools. Owing to this, they shift the paradigm of public participation. Citizens do not remain passive and try to be an active participant in the public life. As a consequence, the actors begin to interact and learn from each other how to use their unique competences to meet all social, public, and economic challenges (Voorberg et al. 2017).

Table 1.

Key stakeholders indicated by social economy organizations (SEOs) (n = 112).

In this context, two key aspects of the occurrence of co-creation in social organizations should be stressed. The first one concerns the creation of social value and social innovation, and the second issue refers to participation in the value chain. Social innovation is defined as a social solution that is new, more efficient, more effective, and more sustainable than the existing ones (Phills et al. 2008). It means that extensive cooperation with stakeholders among social entities results in greater innovativeness (Moulaert and Nussbaumer 2005). Moreover, collaborating with NGOs helps, e.g., enterprises in forming new modes of value creation (Dahan et al. 2010). Those cross-sector partnerships contribute to complementary skills and capabilities along each stage of the value chain. That, in turn, enables these entities to produce new goods or services and to minimize the costs and risks (Bitzer and Glasbergen 2015).

Owing to the close connection between co-creation and SEO activity, as well as social innovation and value creation, it is possible to identify co-creation as a key factor of changes in social entities engaged in commercialization their goods or services.

2.3. Stakeholders

Based on the stakeholder theory (Freeman 2010; Harrison 2014; Parmar et al. 2010) and the role of co-creation actors (Leclercq et al. 2016), a group of the most influential stakeholders—who participated in the process of innovations development, creating a product or a service, and in activities of an organization—was selected. Following the same pattern, a method of analyzing the strength of influence on a social organization along with the mapping method was chosen. The selection was also made on the basis of comments regarding the limited size of stakeholders’ influence (Ćwiklicki 2011).

Each partnership in the value creation process involves stakeholders (Kazadi et al. 2016). An essential criterion for determining whether a given stakeholder was included in the analysis was its importance in the value creation process. The importance was understood as the complementarity of resources and/or capabilities in the value chain (Bitzer and Glasbergen 2015). The most important stakeholders are, on the one hand, businesses, which help a SEO to create a competitive offer by setting and implementing sustainable production standards, and on the other hand, the state, which institutionally supports the SEO and creates new opportunities by public policy planning and supporting SEO projects (Bryson 2004; Bryson et al. 2017; Gouillart 2014). Moreover, the customers play a key role in the process of changing their behavior from passive recipients to active co-designers of value (Prahalad and Ramaswamy 2004; Ramaswamy and Gouillart 2010).

These kinds of partnerships are often called networks due to their multidimensional and multidirectional impact on the interaction process (Bhalla 2010). These relations influence both the value chain and the output. The network structure and the relations between stakeholders are the crucial factors for success (Galvagno and Dalli 2014). That proves that every actor or entity in the chain contributes to value creation by integrating resources. Owing to that, every SEO can benefit from the process of value creation (Gummesson and Mele 2010).

3. Methodology

The research was conducted in 2016–2019 based on a group of SEOs participating in the MOWES project focused on the monitoring of SEOs in the region of Lesser Poland. This research is a part of a broader study on the quality and effectiveness of implementing public support. The research objective of this article is to explore key changes in the mode of operation of Polish social economy organizations that result from a social policy targeted at strengthening their independence and sustainability. It should be emphasized that the research results show preliminary directions of change and indicate a new methodological approach. This analysis can be complemented by further studies providing a detailed description of the phenomenon.

The key research question was, what kind of effects by the commercialization of SEOs’ activities can be occurred? A co-creation model was used to explain this phenomenon. The next research question was focused on whether the policy of the Polish state impacts the commercialization of the entities. What is co-creation and how it applies to the SEOs’ activities? How can the relationships between stakeholders in the co-creation process be described using a matrix of stakeholder participation? Finally, using a co-creation model and a matrix of stakeholders’ participation, how can the effects of SEOs’ commercialization be analyzed? To answer these questions, it was critically important to conduct a study based on SEOs.

The research encompassed 112 SEOs, but only 64 of them took part in all three stages. In the first stage, each SEO was examined before receiving public support. In the next two stages, a satisfaction survey was used in order to analyze how the SEOs’ mode of operation changed after receiving support. The SEOs’ level of satisfaction with the public support system was evaluated twice. First, halfway through the period of receiving the support by an organization and then two months after the end of that period. In the third stage, several obstacles were encountered, as this part of the research was not compulsory, and nearly half of the SEOs did not take part in it. Therefore, some research issues, e.g., the selection of stakeholders, were carried out based on the results from the first stage. However, changes in relationships were investigated only for the participants in all three stages. The first stage involved a direct survey, the second—the CATI method, and the third one—CAWI.

After the survey, further research was conducted to confirm these observations. Additional empirical evidence was collected through in-depth interviews with the project participants and SEO representatives. Over 20 interviews were carried out, but only five were used in this article to demonstrate the interviewees statements. The main aim of the interviews was to identify the causes of and motivation for change in SEOs’ modes of operation. This research strategy allowed the interviewees to explain the role of stakeholders in all activities and stages of the co-creation process. The interviews lasted between 60-70 min. The main interview questions were as follows:

- (1)

- What activities, in comparison to mission-related activities, affected a change in the number of people determining the service implementation?

- (2)

- What was the scale of that change?

- (3)

- What was the reason for the change in the number of people engaged in the decision-making process?

The key elements of the research strategy were (1) selection of stakeholders, (2) matrix development for the analysis of relations between SEOs and stakeholders, and (3) determination of the scale of cooperation between SEOs and stakeholders for activities they were engaged in. Based on the indications of SEOs taking part in the first part of the research, the stakeholders for the survey were selected. In the following stage, only those stakeholders were involved who were indicated by at least 50% of the SEOs (Table 1).

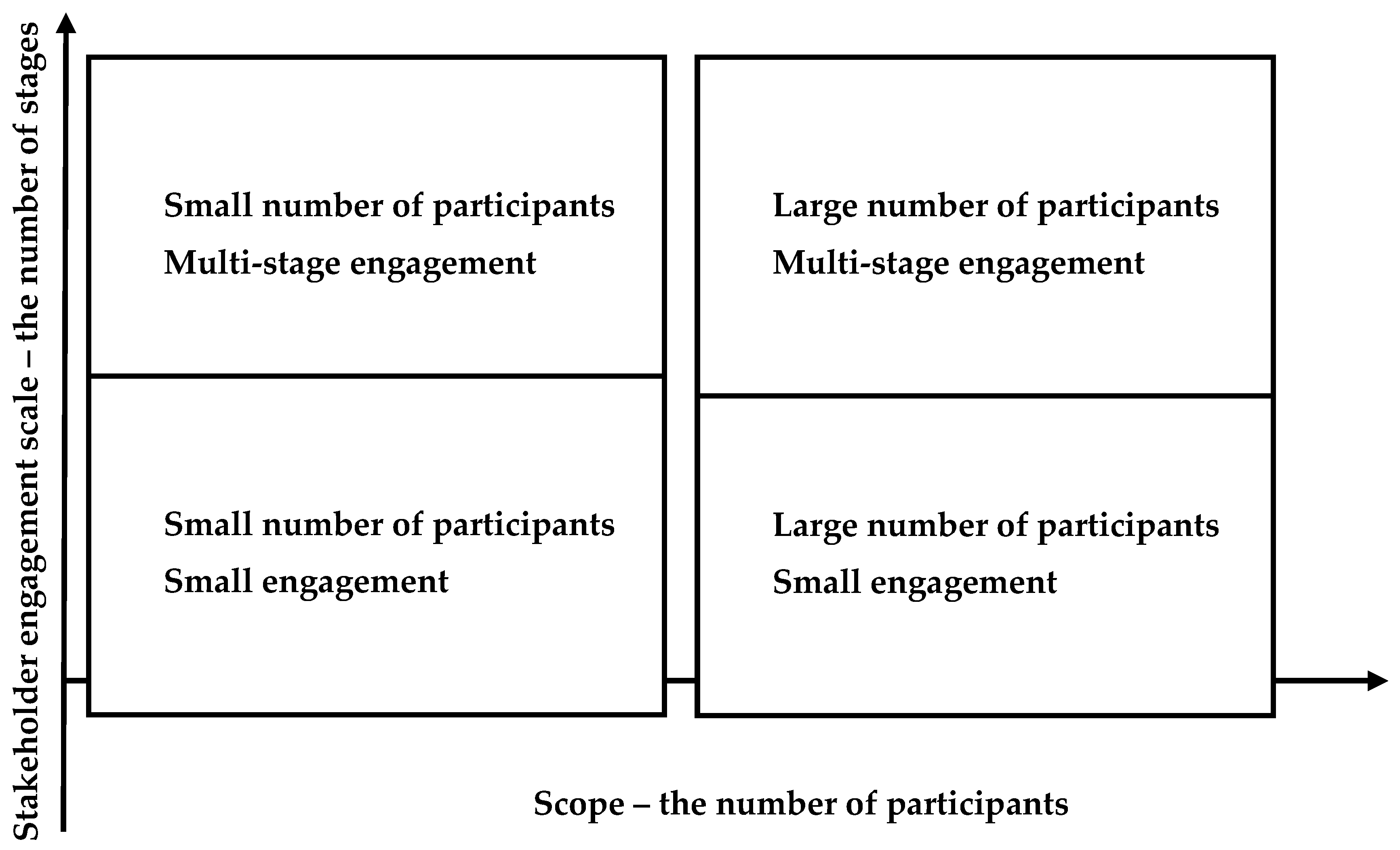

In the next stage, a matrix of relations between SEOs and stakeholders was developed. In line with this, key actors from different stakeholder groups were selected. A few techniques were used to implement this—Bourne’s Stakeholder Circle, Mendelow’s power-interest grid, Murray-Webster and Simon’s three-dimensional grid, and Imperial College London’s influence-interest grid (Chinyio and Olomolaiye 2009). This study is focused, in particular, on the analysis of relations between stakeholders and NGOs (Bryson et al. 2017; Bryson 2004). As a result, only SEOs engaged in economic activities were chosen. In this case, NGOs and social enterprises can build partner relations. Given the other enterprises, these relationships are not treated as partnership but as charity and business (Dahan et al. 2010; Hatch and Schultz 2010). Finally, the matrix was designed using the dimensions of power and influence and number of participants and scale of engagement (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scale and scope of stakeholder engagement. Source: Own study.

In order to analyze the changes, a matrix for stakeholder analysis was adapted (Bryson 2004). The grid enables to place stakeholders in a two-by-two matrix (Figure 1), including the scale of engagement (the number of stages of the product/service development process) and the scope (the number of stakeholders involved in the process). There are four categories of stakeholder involvement:

- (1)

- small scale and small scope—a small number of stages in which stakeholders participate combined with a small number of stakeholders involved throughout the process;

- (2)

- large scale and small scope—a small number of participants in a large number of stages;

- (3)

- small scale and large scope—a large number of participants in a small number of stages;

- (4)

- large scale and large scope—a large number of participants in a large number of stages.

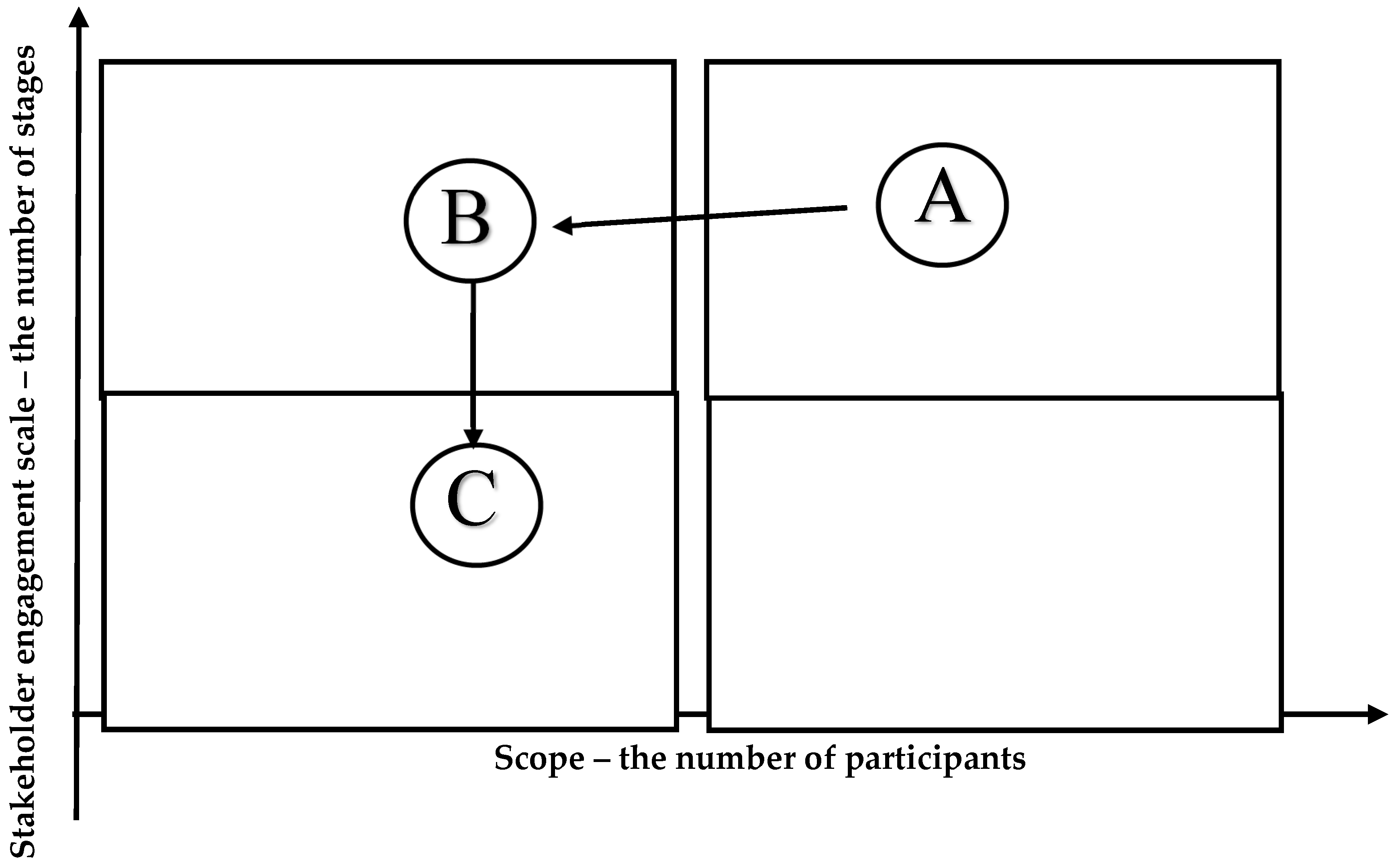

The stakeholder matrix made it possible to analyze stakeholder engagement in the process of inventing and creating a product/service by SEOs (third step). Based on this, the scale and extent of co-creation in the surveyed organizations were determined. Accordingly, the change in the scale and extent of co-creation as an effect of the process of commercialization was explored. The diagram in Conclusions illustrates the tendency observed in this study (Figure 2). In the next stage of the analysis, the type of cooperation in terms of conducted activities was specified. The SEOs’ activities included mission-related activity, paid mission-related activity, and business activity. The scales of co-creation covered as follows: (1) do not participate, (2) allowed to participate, (3) encouraged to participate, (4) engagement in the process, and (5) equal participation (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Changes in the scale of stakeholder engagement depending on the type of activity. A—unpaid mission-related activity, B—paid mission-related activity, C—business activity.

Given the data analysis methods, the surveys were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Due to the small research sample, it was not possible apply a more advanced statistical method. The sample included 64 organizations that took part in all three stages of the research. The dominant turned out to be a relevant measure in the analysis as it unambiguously identified the prevalent type of relation chosen by SEOs. Each organization was asked to select three most frequently used types of relations with stakeholders (“1” being the most popular and “3” the third most popular one).

4. Results

The research has shown that the greater the market engagement of social economy organizations, the lower the stakeholder participation in the products, services, and innovations development (Table 3). In addition, among stakeholders, the role of customers in creating and solving problems related to SEO services is largely reduced. That means that SEOs change their mode of operation. An important change effect includes a move away from activities based on cooperation with stakeholders and high or medium customer engagement in services development. Only a few organizations show an engagement in this regard. The dominant shifts toward creating participation opportunities. Another often indicated effect is a lack of participation in creating and delivering services.

Some of the surveyed organizations did not run and do not intend to conduct business activities. In these SEOs, a change in the approach to co-creation of paid and unpaid services was observed. For unpaid services, the preference for strong stakeholder involvement in the creation and implementation of services was noticeable. In case of paid services, the level of SEO engagement in services development visibly declined. The SEOs engaged in economic activities were additionally examined using qualitative research based on in-depth interviews. Five interviews were conducted to identify the cooperation motives with stakeholders (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in SEOs’ activities and the scale of stakeholder engagement in the decision process.

The study also focused on the payment for services and the professionalization of the provision of services. The results demonstrated that the respondents engaged in the business activities had a conservative approach. Each respondent claimed that business activities required the professionalization of services. The professionalization was understood as “good judgment in decision-making,” “business and professional experience,” and “flexibility and decision-making ability.” The respondents suggested that if an organization intends to conduct business activities, it should be professionally managed, and decision-making should take place in small groups.

However, when a payment was introduced for services offered as part of the entity’s mission, the need for professionalization has not been indicated so often. The most common respondent statement was, “customer engagement in services development is crucial because the services are tailored to the customer.” However, the customer is no longer enabled to make decisions. The introduction of payment shifts the decision-making back to the organization—“financial decisions cannot be taken by customers,” “the customer would demand a lower price,” and “the customer is guided by her interest, not the interest of the SEO.”

The survey conducted on SEOs carrying out all types of activities—unpaid, paid, and business—demonstrates their professionalization and the growing commercialization of their services. The former means limiting the stakeholder role and engagement in creating and delivering services. The business activities imply a radical change in the business model.

The survey among SEOs offering unpaid and paid mission-related activities shows that the introduction of service payments changes the stakeholders’ perception. The change is not significant, but it is important. Using the classification presented in Table 3, the respondents could select between the following options: “create participation opportunities” rather than “equal participation.” Supplementary qualitative studies explain why that happens. Leaders/managers of SEOs recognize that the adoption of payments introduces new elements to the SEO-customer relationship: price, profit, and costs. As a result, the relationship between the SEO and the customer changes into a relationship between two market players. However, in the case of paid and unpaid mission-related activities, SEO managers support customer engagement in the creation and implementation of services. Moreover, due to the fact that the conducting of business activities is often concerned as a priority, the relationships with customer changes from a co-worker relationship into an opponent relationship. According to the interviewed managers, the customer is more interested in profit than in the win-win principle. Based on the conducted research and analysis, it seems that SEO managers themselves implement the concept of a non-zero-sum game. In line with this, a new question arises: whether the buyers of SEOs services actually follow the win-lose principle or whether it is just the managers’ projection. To answer this question, however, further studies are required.

Table 3.

Stakeholders engagement in SEO operation depending on the type of activities.

The “x” signs in the Table 2 denote the first, second and third choice of the respondents answering the following three survey questions: (1) What kind of cooperation with stakeholders dominates in your unpaid activities? (2) What kind of cooperation with stakeholders dominates in your paid activities? (3) What kind of cooperation with stakeholders dominates in your business activities? For each type of activity, the respondents could give three answers, where “1” implied the most popular scale of SEO involvement and “3” the third most popular one. To indicate the strength of impact, signs were used rather than numbers. “XXX” denotes the dominant answers for the first choice, “XX” is the dominant for the second choice, and “X” for the third one. This differentiation allows visualizing the similarity between answers and the scale of change in stakeholder engagement. The value of the determinant for a given answer is shown in the brackets below the signs.

The research analysis demonstrates a difference between the behavior of SEOs and the way of treating shareholders depending on a type of activities. It can be noticed that, for mission-related activities, the SEOs mostly show an open attitude to their stakeholders. “Engagement in the process” is indicated as the first choice and “encouraged to participate” is the second choice for a large majority of respondents. Most people surveyed select “equal participation” as the third option. Due to an open approach toward their activities, the SEOs use extensive stakeholder cooperation in creating services, products, and other solutions for their mission-related activities. The introduction of paid mission-related activities contributes to these slight changes. Compared to a situation when there are no paid activities, the role of stakeholders for the SEOs is more limited. The two first choices remain the same, but the third one changes. The entities omit “equal participation” and select “allowed to participate” instead. The research results clearly show a diminishing participation of stakeholders in this process. However, the greatest change in the perception of the role of stakeholders occurs when business activity is launched. The SEOs conducting business activity, in contrast to mission-related activity, significantly reduce the participation of their stakeholders in the creation of goods and services. They opt for professionalization, which they understand in market-related terms. This leads to decreasing stakeholder participation and changing the relations with them into more business-oriented and also in paid ones. The respondents indicate “allowed to participate” as their first choice and “do not participate” as their second choixe. That significantly differs from the answers concerning other types of activities conducted by those SEOs.

As SEOs increased the scope of their activity by the implementation of the project, it can be concluded that it is not just a description of a static situation but, rather, a demonstrating a change perspective in the type of conducted activities. In line with this, SEOs change their business model and partially turn into a typical market company. Their business model is definitely closer to the traditional, closed model rather than to an open one with a significant role of stakeholders (Von Scheel et al. 2015). The SEOs limit their contact and relations with stakeholders in the creation process. They also reduce their role in the assessment of the solutions they use. The in-depth interviews also displayed changes in marketing and even in the outsourcing of services, e.g., legal or accounting. Before participating in the project, they used those services for free as part of a cooperation with stakeholders. After launching business activities, they took a different approach to business services. Another important aspect is a reduction of external services and an attempt to offer them by the SEO. Similar attitudes were observed in a study of social enterprises (Scott-Kemmis 2012).

Figure 2 shows these dependencies visually. A change in the type of activity is accompanied by a change in approach to stakeholders. The more important is the financial result of an entity’s activity, the relations with stakeholders become more and more limited. As a consequence, conducting business activity significantly decreases the scale of stakeholder engagement in creating goods and services.

5. Conclusions

Co-creation as a business model is a natural approach to show how SEOs pursue their mission by extensive using of stakeholder engagement in their activities. Stakeholders support the activities of SEOs, including external services, consulting etc. Stakeholders and, in particular, customers play an important role in the value creation chain. The introduction of a new development path changes the mode of operation used by these entities. The introduction of payments, especially income-earning opportunities, changes the way in which a SEO operates. The implementation of commercialization, however, makes a SEO’s mode of operation more similar to the business model of market entities. This is an interesting example of change because the natural way of SEO activity is a broad involvement of stakeholders in the creation of products and services (Laville et al. 2005). The launch of business activities entails changes in those relationships and brings the SEO closer to a conservative business model, which radically hampers the access of non-business partners. This happens despite the fact that a SEO conducts parallel mission-related activities, where co-creation is a basic element of the applied business model. The results of this research indicate that the problem requires more detailed studies.

The research objective of this article was to explore changes in SEOs’ mode of operation following the commercialization of their activities. Based on the conducted research, it can be stated that each type of SEO activity is characterized by a different scope and scale of cooperation with stakeholders. The more advanced financially and economically an activity is, the more limited was the cooperation with stakeholders. The most significantly factor reducing the involvement of stakeholders in the creation of goods or services is the conducting business activity by an SEO.

In this context, it is worth pointing out that, by implementing a public policy supporting the commercialization of SEO activities, the state may limit the positive social impact of their activity (Farazmand 2018; Vaceková and Svidroňová 2014). In particular, it may concern building social capital, developing broad social bonds, and providing social services and innovation matching people’s needs based on an extensive cooperation with stakeholders (Moulaert and Ailenei 2005). Those observations show an important dilemma whether providing social services by SEOs should be supported by the public policy in or whether their independence and development should be promoted by commercialization. That area requires further studies.

The results of the analysis allowed for the answers to the research questions. The main question of the study was what kind of effects occur with the commercialization of SEOs activities? The research identified relationships between SEOs and stakeholder specifying each type of activity. Change in the kind of activity is accompanied by a changed involvement of stakeholders in creating goods and services. The next research question focused on how the relationships between stakeholders in the co-creation process can be described using a matrix of stakeholder participation? Owing to the matrix, developed in this study, the involvement of stakeholders in creating goods and services has been demonstrated. The matrix includes both the scope and the scale of the involvement. Finally, using a co-creation model and a matrix of stakeholder participation, the third question referred to the issue of how the effects of SEOs’ commercialization can be analyzed. The matrix shows that the change in stakeholder involvement is a result of the change in SEO activity. The level of involvement significantly decreases with a growing professionalization of the activities resulting from the commercialization of SEOs activities.

The research conducted on 112 entities in the region of Lesser Poland in 2016–2019 shows several directions of further studies. A sample issue of further research could include the question, to what extent can commercialization lead to a complete change in a way a SEO operates? To sum up, it can be stated that the support of SEO independence and sustainability can lead to the redefinition of their mission and reorientation of their social goals. The greater is their involvement in business activity, the more their way of operating can change.

Author Contributions

The author worked on the thesis independently.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alter, Kim. 2007. Social Enterprise Typology; Virtue Ventures. Available online: https://www.globalcube.net/clients/philippson/content/medias/download/SE_typology.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2019).

- Amin, Ash. 2009. The Social Economy: Alternative Ways of Thinking about Capitalism and Welfare, 1st ed. London and New York: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Beugelsdijk, Sjoerd, and Sjak Smulders. 2009. Bonding and Bridging Social Capital and Economic Growth. SSRN Scholarly Paper. ID 1402697. Rochester: Social Science Research Network. [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla, Gaurav. 2010. Collaboration and Co-Creation: New Platforms for Marketing and Innovation, 2011st ed. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bitzer, Verena, and Pieter Glasbergen. 2015. Business-NGO Partnerships in Global Value Chains: Part of the Solution or Part of the Problem of Sustainable Change? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 12: 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, William R. 2012. The Sustainability Handbook: The Complete Management Guide to Achieving Social, Economic and Environmental Responsibility. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bohdziewicz-Lulewicz, Marta, and Anna Rychły-Mierzwa. 2018. Monitoring Kondycji Sektora Ekonomii Społecznej w Małopolsce [Monitoring of Social Economy Condition in Malopolska]. Kraków: Regionalny Ośrodek Polityki Społecznej w Krakowie. [Google Scholar]

- Borzaga, Carlo, and Jacques Defourny. 2004. The Emergence of Social Enterprise. London: Psychology Press, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Borzillo, Stefano, Daniel Schwenger, and Thomas Straub. 2014. Non-Governmental Organizations: Strategic Management for a Competitive World. Journal of Business Strategy 35: 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, John M. 2004. What to Do When Stakeholders Matter. Public Management Review 6: 21–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, John, Alessandro Sancino, John Benington, and Eva Sørensen. 2017. Towards a Multi-Actor Theory of Public Value Co-Creation. Public Management Review 19: 640–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinyio, Ezekiel, and Paul Olomolaiye. 2009. Construction Stakeholder Management. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Ćwiklicki, Marek. 2011. Analiza interesariuszy w koncepcji relacji złożonych procesów reakcji. Zeszyty Naukowe, Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny w Poznaniu 199: 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Czapiński, Janusz, and Tomasz Panek. 2015. Diagnoza Społeczna 2015—Warunki i jakość życia Polaków - Biblioteka Cyfrowa. Warszawa: Rada Monitoringu Społecznego. [Google Scholar]

- Dahan, Nicolas M., Jonathan P. Doh, Jennifer Oetzel, and Michael Yaziji. 2010. Corporate-NGO Collaboration: Co-Creating New Business Models for Developing Markets. Long Range Planning 43: 326–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koning, Jotte, Marcel Crul, and Renee Wever. 2016. Models of Co-Creation. Paper presented at Service Design Geographies 2016 Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark, May 24–26, vol. 125. [Google Scholar]

- Defourny, Jacques. 2001. Social Enterprise and the Third Sector. In The Emergence of Social Enterprise. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, Adalbert. 2001. The Significance of Social Capital in the Multiple Goal and Resource Structure of Social Enterprises. Available online: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/rout/c3gab/2001/00000001/00000001/art00019;jsessionid=dr0eeo68f0157.x-ic-live-01 (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- Farazmand, Ali, ed. 2018. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Berlin: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R. Edward. 2010. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fudaliński, Janusz. 2014. Dysfunctions of NPOs and NGOs in Poland in the Global Context: Some International Comparisons. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review 2: 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Galvagno, Marco, and Daniele Dalli. 2014. Theory of Value Co-Creation: A Systematic Literature Review. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal 24: 643–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouillart, Francis. 2014. The Race to Implement Co-Creation of Value with Stakeholders: Five Approaches to Competitive Advantage. Strategy and Leadership 42: 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummesson, Evert, and Cristina Mele. 2010. Marketing as Value Co-Creation Through Network Interaction and Resource Integration. Journal of Business Market Management 4: 181–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Jeffrey S. 2014. Strategic Management of Healthcare Organizations: A Stakeholder Management Approach. New York: Business Expert Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch, Mary, and Majken Schultz. 2010. Toward a Theory of Brand Co-Creation with Implications for Brand Governance. Journal of Brand Management 17: 590–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausner, Jerzy, and Norbert Laurisz. 2008. Czynniki krytyczne tworzenia przedsiębiorstw społecznych. Przedsiębiorstwo społeczne. Konceptualizacja. In Przedsiębiorstwa Społeczne w Polsce: Teoria i Praktyka. Kraków: Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny, Małopolska Szkoła Administracji Publicznej. [Google Scholar]

- Hausner, Jerzy, Norbert Laurisz, and Stanisław Mazur. 2007. Przedsiębiorstwo Społeczne—Konceptualizacja [The concept of social enterprises]. In Managing Social Economy Institutions, Course Book. Krakow: Małopolska School of Public Administration, Krakow University of Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell, John F., and Robert D. Putnam. 1995. Economic Growth and Social Capital in Italy. Eastern Economic Journal 21: 295–307. [Google Scholar]

- Kazadi, Kande, Annouk Lievens, and Dominik Mahr. 2016. Stakeholder Co-Creation during the Innovation Process: Identifying Capabilities for Knowledge Creation among Multiple Stakeholders. Journal of Business Research 69: 525–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopyciński, Piotr. 2017. The neo-Weberian Approach in Innovation Policy. In Public Policy and the Neo-Weberian State. Edited by Stanisław Mazur and Piotr Kopyciński. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 80–94. [Google Scholar]

- Laurisz, Norbert, and Stanisław Mazur. 2008. Kluczowe czynniki rozwoju przedsiębiorczości społecznej. In Ekonomia Społeczna w Polsce: Osiągnięcia, Bariery rozwoju i Potencjał w Świetle Wyników Badań. Warszawa: Fundacja Inicjatyw Społeczno-Ekonomicznych, pp. 315–31. [Google Scholar]

- Laville, Jean-Louis, and Marthe Nyssens. 2001. The Social Enterprise. Available online: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/rout/c3gab/2001/00000001/00000001/art00020 (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- Laville, Jean-Louis, Benoît Lévesque, and Margueritte Mendell. 2005. The Social Economy: Diverse Approaches and Practices in Europe and Canada. Paris: OECD, pp. 125–73. [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq, Thomas, Wafa Hammedi, and Ingrid Poncin. 2016. Ten Years of Value Cocreation: An Integrative Review. Recherche et Applications En Marketing (English Edition) 31: 26–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajczak, Paweł. 2017. Importance of Funding Sources to the Scale of Activity of Social Enterprises. Finanse, Rynki Finansowe, Ubezpieczenia 88: 135–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajczak, Paweł. 2018. The Impact of the Diversification of Revenues on NGOs’ Commercialization: Evidence from Poland. Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy 13: 761–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikucka, Malgorzata, and Francesco Sarracino. 2014. Making Economic Growth and Well-Being Compatible: The Role of Trust and Income Inequality. Munich: University Library of Munich. [Google Scholar]

- Moulaert, Frank, and Oana Ailenei. 2005. Social Economy, Third Sector and Solidarity Relations: A Conceptual Synthesis from History to Present. Urban Studies 42: 2037–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, Frank, and Jacques Nussbaumer. 2005. Defining the Social Economy and Its Governance at the Neighbourhood Level: A Methodological Reflection. Urban Studies 42: 2071–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnenkamp, Peter, and Hannes Öhler. 2010. Funding, Competition and the Efficiency of NGOs: An Empirical Analysis of Non-Charitable Expenditure of US NGOs Engaged in Foreign Aid SSRN Electronic Journal. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hern, Matthew S., and Aric P. Rindfleisch. 2010. Customer Co-Creation: A Typology and Research Agenda. Review of Marketing Research 6: 84–106. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, David L., Sang M. Lee, and Silvana Trimi. 2012. Co-innovation: Convergenomics, Collaboration, and Co-creation for Organizational Values. Management Decision 50: 817–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pacut, Agnieszka. 2010. Przedsiębiorczość społeczna w Polsce—Problemy i wyzwania [Social entrepreneurship in Poland: Problems and challenges]. Zarządzanie Publiczne 4: 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Parmar, Bobby, R. Freeman, Jeffrey Harrison, A. Purnell, and Simone De Colle. 2010. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art. The Academy of Management Annals 3: 403–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrini, Francesco. 2006. The New Social Entrepreneurship: What Awaits Social Entrepreneurial Ventures? Cheltenham: Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Phills, James, Kriss Deiglmeier, and Dale Miller. 2008. Rediscovering Social Innovation. Stanford Social Innovation Review 6: 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pinho, Nelson, Gabriela Beirão, Lia Patrício, and Raymond P. Fisk. 2014. Understanding Value Co-Creation in Complex Services with Many Actors’. Journal of Service Management 25: 470–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C. K., and Venkat Ramaswamy. 2004. Co-Creation Experiences: The next Practice in Value Creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing 18: 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, Venkat, and Francis Gouillart. 2010. Building the Co-Creative Enterprise. Harvard Business Review 88: 100–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy, Venkat, and Kerimcan Ozcan. 2013. Strategy and Co-Creation Thinking. Strategy and Leadership 41: 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, Venkat, and Kerimcan Ozcan. 2014. The Co-Creation Paradigm. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sarracino, Francesco, and Małgorzata Mikucka. 2017. Social Capital in Europe from 1990 to 2012: Trends and Convergence. Social Indicators Research 131: 407–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenger, Daniel, Thomas Straub, and Stefano Borzillo. 2013. Competition and Strategy of Non-Governmental Organizations. EMES-SOCENT Conference Selected Papers, no. LG13-, Liège. Available online: https://emes.net/content/uploads/publications/Schwenger_at_al._ECSP-LG13-45.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2019).

- Scott-Kemmis, Don. 2012. Responding to Change and Pursuing Growth: Exploring the Potential of Business Model Innovation in Australia. Sydney: Australian Business Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Spear, Roger, Jacques Defourny, and Jean-Louis Laville. 2018. Tackling Social Exclusion in Europe: The Contribution of the Social Economy. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vaceková, Gabriela, and Má Svidroňovária. 2014. Benefits and Risks of Self-Financing of NGOS: Empirical Evidence from the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Austria. E a M: Ekonomie a Management 17: 120–29. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, Stephen L., and Robert F. Lusch. 2004. Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. Journal of Marketing 68: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, Stephen L., Paul P. Maglio, and Melissa Archpru Akaka. 2008. On Value and Value Co-Creation: A Service Systems and Service Logic Perspective. European Management Journal 26: 145–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, Fernand. 2006. NGOs, Social Movements, External Funding and Dependency. Development 49: 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Scheel, Henrik, Zakaria Maamar, and Mona von Rosing. 2015. Social Media and Business Process Management. In The Complete Business Process Handbook. Edited by Mark von Rosing, Henrik von Scheel and August-Wilhelm Scheer. Boston: Morgan Kaufmann, pp. 381–98. [Google Scholar]

- Voorberg, William, Victor Bekkers, and Lars Tummers. 2015. A Systematic Review of Co-Creation and Co-Production: Embarking on the Social Innovation Journey. Public Management Review 17: 1333–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorberg, William, Victor Bekkers, Krista Timeus, Piret Tonurist, and Lars Tummers. 2017. Changing Public Service Delivery: Learning in Co-Creation. Policy and Society 36: 178–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, Rob. 2001. Ensuring NGO Independence in the New Funding Environment. Development in Practice 11: 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wygnański, Jakub, and Piotr Frączak. 2008. The Polish Model of the Social Economy Recommendations. Warsaw: Foundation for Social and Economic Initiatives. [Google Scholar]

- Żur, Agnieszka. 2014. Building competitive advantage through social value creation—A comparative case study approach to social entrepreneurship. Problemy Zarządzania 4: 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).