Deaf and hard-of-hearing children (hereafter referred to as deaf) represent a heterogeneous population with varied linguistic and cognitive backgrounds. This variability reflects complex traits shaped by individual differences and their environments (

Smith & Allman, 2020). Research on deaf children’s development must consider factors beyond hearing level. Cultural identities (

Byatt et al., 2021), multilingual language environments (

Crowe, 2019), and the presence of additional disabilities (

Bowen & Probst, 2023) all play a pivotal role in shaping a deaf child’s language and cognition. This diversity leads to variability in outcomes like language expression, social interaction, cognition, and executive functioning, which have major implications for education. This is especially true as inequities in academic attainment persist (

Garberoglio et al., 2021) despite advancements in crucial supports like newborn hearing screening and identification (

Yoshinaga-Itano et al., 1998) and early intervention (

Meinzen-Derr et al., 2020). Research that centers these diverse experiences works to expand developmental theory and improve instructional approaches for a broad range of learners.

1.1. Language Foundations

Early exposure to language-rich environments is essential for literacy development. For deaf children, consistent access to signed or spoken language is vital for growth in literacy and cognition. There are multiple pathways to language proficiency for deaf children (

M. L. Hall et al., 2019). Some recommend against learning sign language alongside spoken language (

Geers et al., 2017) due to misconceptions about neural plasticity (

Cheng et al., 2019), language acquisition (

Pontecorvo et al., 2023), and hearing parents’ capacity to learn and model sign language (

Lieberman et al., 2022). However, research shows that both signed and spoken input support strong language foundations and cognitive growth (

Delcenserie et al., 2024). Even caregivers who are learning sign language alongside their deaf child can offer ample language input to support age-appropriate vocabulary development (

N. Caselli et al., 2021;

Finton et al., 2024), reinforcing the importance of early, accessible communication, regardless of modality (

Allen & Morere, 2020).

Along with newborn hearing screening and early intervention services, hearing technology has seen a dramatic increase in sophistication and availability, leading to increasingly earlier access to auditory input (

Naik et al., 2021). It is important, however, to distinguish between quality access to technology and quality access to actual language, as the mere use of a device does not guarantee optimal language input (

Carrigan & Coppola, 2020), nor should early access to technology be considered the dominant variable influencing language growth (

Duchesne & Marschark, 2019).

Early and accessible language fosters cognitive–linguistic skills that enhance later learning. For example, consistent language input in a deaf child’s early years is crucial for developing receptive vocabulary—the building blocks of language and literacy (

Allen & Morere, 2020). Additionally, early communication with caregivers develops visual attention, essential for visual language acquisition (

Dye & Hauser, 2014;

Singleton & Morgan, 2006) and executive function skills (

Hauser et al., 2008). Research has shown how deeply interconnected these processes are, pointing to language as a key mediator in developing executive functioning (

Botting et al., 2016). Early interactions also foster theory of mind (

Meristo et al., 2007;

Schick et al., 2007) and working memory (

Marshall et al., 2015), both linked to early literacy (

Tucci & Easterbrooks, 2020). Foundational language skills shape later reading development, including vocabulary knowledge (

N. Caselli et al., 2021) and orthographic awareness (

Allen et al., 2014), underscoring the importance of early and accessible language for cognition and literacy outcomes (

Gabriel et al., 2025).

1.2. Literacy Foundations and Performance

Given the diverse backgrounds and language experiences of deaf children, literacy performance data should be collected and interpreted through a context-sensitive lens (

Gabriel & Dostal, 2013;

P. J. Graham & Shuler-Krause, 2020). Recent large-scale research points to the expressive language diversity of deaf children to explain diverse developmental paths in literacy. Deaf students show similarities in the underlying skills needed for early reading, such as a strong expressive/receptive language foundation and sublexical processing of word reading; however, these skills vary in application by visual or spoken language modalities (

Lederberg et al., 2019).

When provided a linguistically accessible reading curriculum, deaf children demonstrate progress in early reading skills.

Antia et al. (

2020) collected language and literacy data with 336 deaf children in kindergarten through second grade at the beginning and end of one academic year. The sample was organized into three language modality groups: spoken only, sign only, and bimodal. Those with functional hearing showed growth in English and spoken phonological knowledge. Signing deaf students demonstrated growth in American Sign Language (ASL) syntax and fingerspelling phonological knowledge. Both types of phonological knowledge are pathways to decoding words using sublexical processes. When phonological knowledge (whether spoken or fingerspelled) aligns with the way words are stored in students’ cognitive systems (as sound-based or visual-based), comprehension is bolstered (

Lederberg et al., 2019). Considering the extensive heterogeneity of this population, these findings highlight the complex ways that individual experiences (e.g., early language access, cognitive development, cultural background) and language dispositions interact with learning environments to shape language and literacy outcomes.

The last decade of research on language and literacy outcomes brings a growing awareness of the varied developmental trajectories of deaf children. It is becoming increasingly clear that the variability in performance does not reflect a deficit model (i.e., the idea that deaf children plateau at a certain point in their capability to develop new reading skills). Instead, multiple valid developmental pathways are present, which challenge the belief that there is a single correct normative trajectory (

Cawthon et al., 2022).

Cawthon et al. (

2022) analyzed NWEA MAP reading and math assessment outcomes for 351 deaf students attending schools for the deaf, as well as a group of hearing students, over a five-year period. Second- through eighth-grade deaf students demonstrated steady growth, making similar annual gains in all domains as their hearing peers. This asset-oriented perspective invites researchers and educators to dig deeper into patterns of consistent growth and consider diverse strengths in the ways that deaf children learn.

The development of writing skills is also deeply intertwined with early language acquisition. Writing is a demanding and complex process that draws upon numerous linguistic and cognitive skills, including vocabulary, syntax, idea organization, and metalinguistic awareness. Unlike reading, in which language is received through decoding, writing requires students to draw from their language repertoire to encode novel ideas. This means that a child’s writing experiences are directly mediated by their unique idiolects. Just as emergent readers benefit from instructional strategies that align with their sound-based and/or sign-based cognitive systems (

Lederberg et al., 2019), early writers benefit from explicit instruction with translating ideas and encoding language by drawing upon and expanding their current linguistic structures (

K. Wolbers et al., 2023b). For monolingual children developing listening and spoken language, teachers support writing skills by attending to students’ expressive and receptive language development, along with explicit instruction in how they represent that language in written form (

S. Graham & Perin, 2007). Bilingual and multilingual students naturally draw from all of their language resources during the composing process. When a student communicates through multiple languages and modalities (e.g., signed, written, spoken), translanguaging theory explains that they do not compartmentalize their languages (

García et al., 2017); rather, they are “working from their single, unified linguistic system during meaning-making processes, tapping into all words, linguistic features, and semiotic resources they know to express ideas in print” (

Holcomb, 2023, p. 3). When learning a new target language, multilingual students benefit from writing instruction that validates and engages all of their linguistic resources while heightening their metalinguistic awareness.

Through specialized language instruction, students are empowered to expand and flexibly draw on a broader range of language practices to communicate effectively with various audiences and for diverse purposes.

Tang et al. (

2023), for instance, studied the syntactic development of written Chinese (a non-alphabetic language) among deaf elementary students while providing “flexible code choice” (p. 693) in Hong Kong Sign Language and spoken Cantonese instruction within a sign bilingual co-enrollment (SLCO) setting. In this study, hearing (multilingual) students enrolled in the same SLCO classrooms served as the control group. The researchers found that, despite modality and structural differences across Hong Kong Sign Language, spoken Cantonese, and written Chinese, the deaf students developed written Chinese grammatical skills in a similar order to their hearing peers. While these syntactic skills were initially gained at a slower rate compared to their hearing peers, the deaf students narrowed the gap over time, showing consistent progress across elementary grades.

Another concern discussed in the field is whether the acquisition of a signed language can interfere with the development of written language. Elements from one language sometimes appear in another, such as phonological or grammatical features of Spanish or ASL within English text (

Holcomb, 2023;

K. A. Wolbers et al., 2014). These applications are an expected and natural feature of multilingual development (

Rubin & Carlan, 2005) and provide evidence of a writer accessing their whole linguistic repertoire to compose and share their ideas (

García et al., 2021). Like a web, a writer’s linguistic repertoire is comprised of many linguistic resources that span across modalities and languages, and it grows organically through meaningful interactions with others. Writing for different authentic purposes and audiences further encourages the curation and adaptation of language features that support a writer’s goals. In a qualitative case study that centered on the writing of three young deaf siblings across 10 years,

Holcomb (

2023) examined the writing development and translanguaging features within 28 written samples. These writers, aged three-to-ten years old, were raised and educated in ASL/written English environments, and their writing demonstrated all of the stages of emergent writing development. Translanguaging features (e.g., embedded applications of linguistic structures) were identified in earlier writings, demonstrating how the young writers leveraged their linguistic repertoires as they developed new language skills. As they grew older and their metalinguistic awareness matured, these features decreased as they deployed linguistic resources that were increasingly appropriate to their intended audience, purpose, format, and language.

Given this perspective of how deaf students use their linguistic resources to construct meaning, there are important implications for how teachers and researchers approach the evaluation of their writing.

García et al. (

2017) propose that purposeful assessments should be designed through the lens of translanguaging theory; however, many of the tools and approaches available to teachers are normed and designed for hearing, monolingual learners (

Holcomb & Lawyer, 2020). This gap between theory and practice points to the significance in conducting broad-ranging research that captures how deaf students develop language skills and communicate through their writing. In an analysis of a large collection of writing samples using a functional grammar framework (

Kilpatrick & Wolbers, 2020), the authors map the progression of syntactic structures used by students, providing a view into their writing development. They found that emergent writers tended to express ideas through one-word nouns and simple sentences, while more fluent writers expanded noun phrases, used adverbs, and embedded clauses. While writing outcomes for deaf students demonstrate wide variability, studying these patterns in development helps researchers and educators recognize the strengths and trajectories in all students’ writing. Meaningful and sustained progress is achievable when instruction and assessment tools are responsive to students’ linguistic experiences.

1.3. Demographic Factors and Literacy Outcomes

Research has examined how demographic factors such as hearing level, gender, race, and family hearing status relate to the literacy development of deaf students. Some studies have found that students with mild-to-moderate hearing levels (

Tomblin et al., 2020) or unilateral hearing loss (

Mayer et al., 2021) perform better on standardized assessments than peers with severe hearing levels and bilateral hearing loss. Other studies, however, have shown that even a mild hearing difference can impact access to language and instruction in meaningful ways (

Marschark et al., 2015;

Reijers et al., 2024). Hearing technologies are utilized to enhance children’s access to spoken language, and the consistency of technology use has been identified as a key predictor of literacy skill development (

Walker et al., 2015). Even so, researchers of the early language and literacy acquisition study found that among aided deaf and hard-of-hearing children who use spoken language, there are significant delays in early language development (

Lund & Werfel, 2025;

Vachio et al., 2023) and emergent literacy skills (

Werfel, 2017) compared to their hearing counterparts.

In terms of gender, research findings have been inconsistent or have mirrored broader trends in general education research (

Mitchell & Karchmer, 2011;

Yoshinaga-Itano, 2003). While disparities in educational access and outcomes persist along racial and socioeconomic lines (

Myers et al., 2010), these factors are often entangled with broader systemic and contextual factors that go well beyond individual student traits. For example, in a study investigating vocabulary across 448 children who were deaf or hard of hearing and who had participated in early intervention,

Yoshinaga-Itano et al. (

2017) found that 41% of the variance in vocabulary performance was explained by a combination of adherence to EHDI guidelines, being younger in age, having no additional disabilities, having a mild-to-moderate hearing level, higher maternal education, and having deaf or hard-of-hearing parent(s). Many other studies have demonstrated favorable literacy outcomes for deaf children who have signing deaf parents (

Scott, 2022). These outcomes have been attributed to early and consistent access to a natural signed language rather than to parental hearing status alone (

Finton et al., 2024).

Studying large datasets provides a valuable lens for understanding the diversity within the deaf student population. Smaller or more homogenous samples are able to control for or focus on certain variables, but a large sample more broadly demonstrates language and literacy outcomes across various educational contexts and diverse learner backgrounds. With large-scale data, researchers can examine how learner variables interact with standardized measures of reading and writing and related subskills. In this study, we analyze results from standardized literacy assessments to explore these interactions. Rather than simply comparing deaf students to normative expectations, our goal is to better understand and examine the variability within this population.

In the current study, we investigated the following research questions:

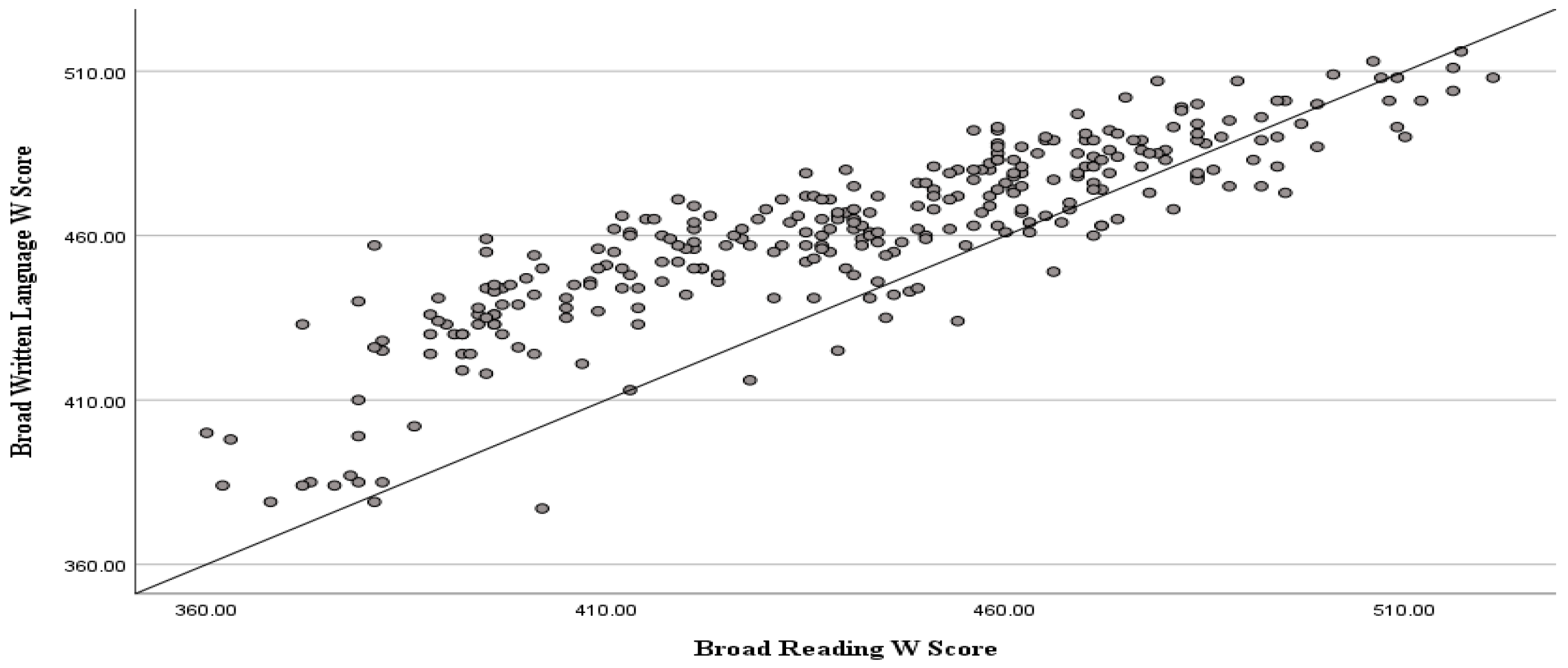

Research Question 1: What are the literacy scores of deaf elementary students in the US? What is the relationship between writing and reading outcomes?

Research Question 2: How do literacy scores vary across student demographic groups?

Research Question 3: How do students’ literacy scores vary based on language proficiency levels?

Research Question 4: To what extent do language proficiency and phonological knowledge (spoken or fingerspelled) explain variance in students’ literacy scores?