A Scoping Review of Literacy Interventions Using Signed Languages for School-Age Deaf Students

Abstract

1. Literature Review

1.1. Sign Language Research

1.2. Literacy and Deaf Children

1.2.1. Literacy and Cognition

1.2.2. Literacy, Sign Language, and Print

1.2.3. Cross-Linguistic Transfer and Justification for Signed Interventions to Support Print Literacy

1.3. Positionality

2. Methods

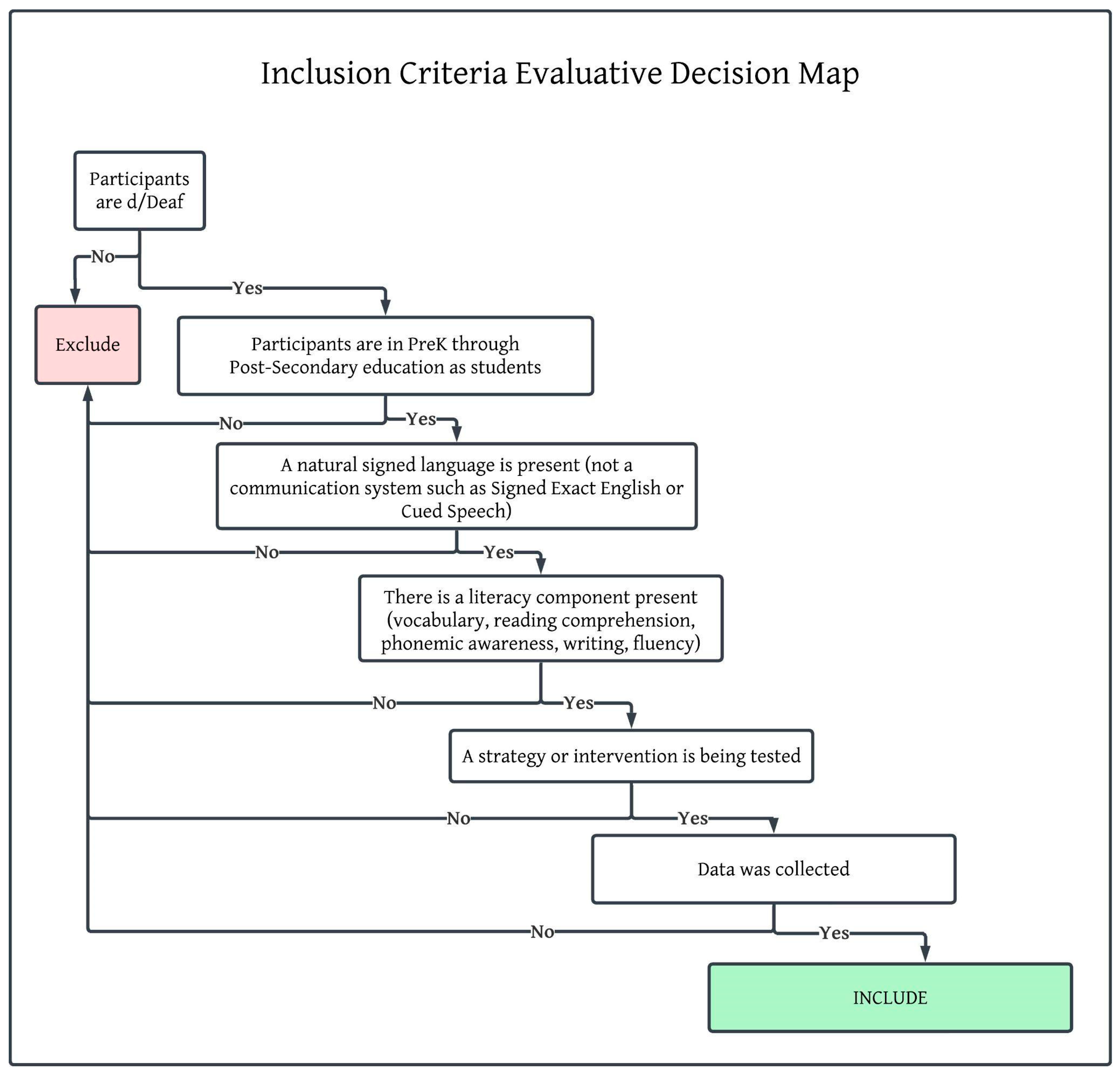

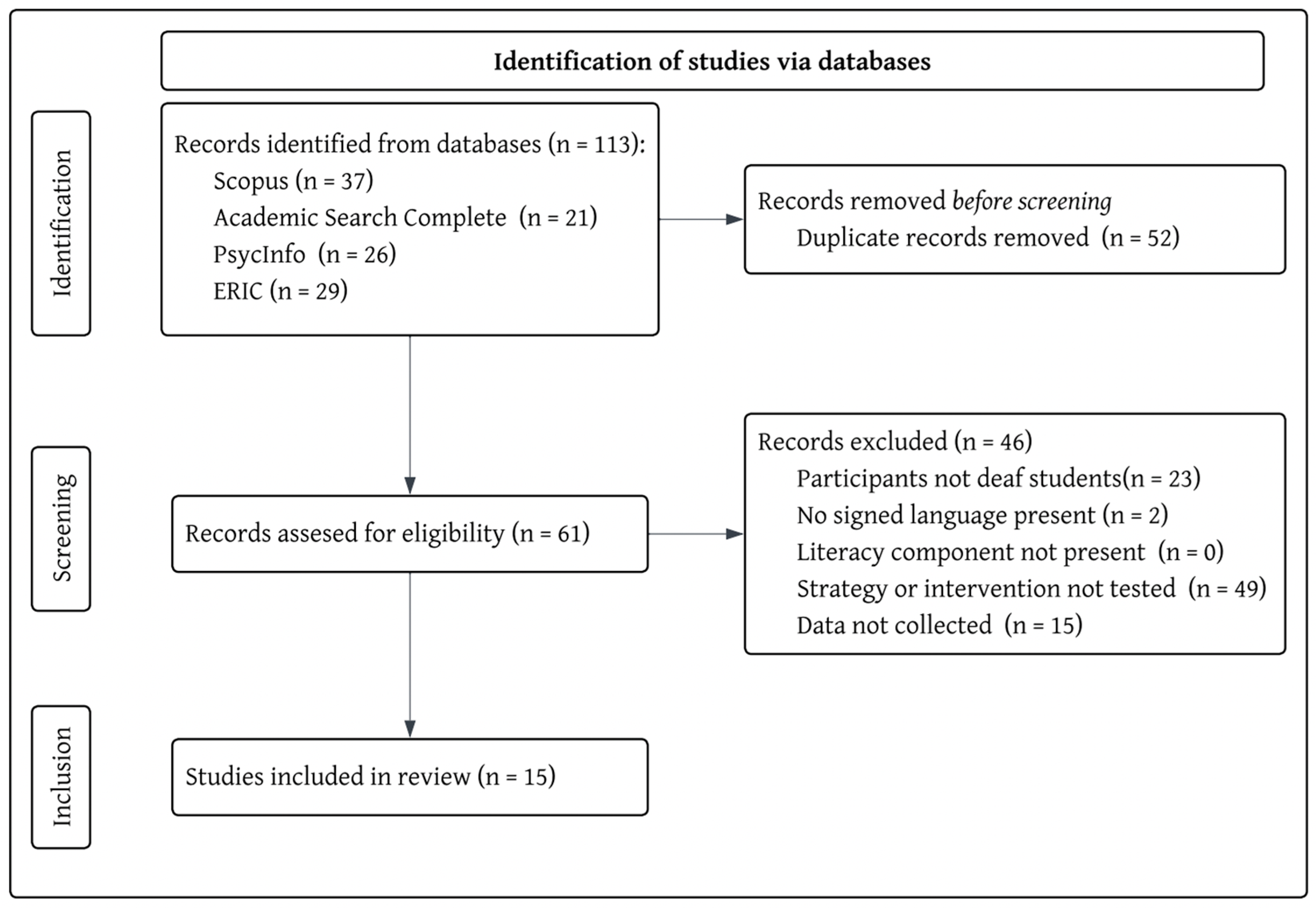

2.1. Protocol

2.2. Analytic Approach

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Sign Languages Used

3.2. Methodological Approach

3.2.1. Quantitative Approaches

3.2.2. Qualitative Approaches

3.3. Strategies or Interventions Used

3.4. Summary of Articles’ Results

3.4.1. Component Literacy Skills

3.4.2. Phonemic Awareness

3.4.3. Phonological Awareness

3.4.4. Fluency

3.4.5. Vocabulary

3.4.6. Comprehension

3.4.7. Composition

4. Discussion

4.1. The Role of Sign Language in Literacy Acquisition

4.2. The Case for Sign Language Oriented Classrooms

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, T. E., Letteri, A., Choi, S. H., & Dang, D. (2014). Early visual language exposure and emergent literacy in preschool deaf children: Findings from a national longitudinal study. American Annals of the Deaf, 159(4), 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allor, J. H., Yovanoff, P., Otaiba, S. A., Ortiz, M. B., & Conner, C. (2020). Evidence for a literacy intervention for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 55(3), 290–302. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, J. F., & Baker, S. (2019). ASL nursery rhymes: Exploring a support for early language and emergent literacy skills for signing deaf children. Sign Language Studies, 20(1), 5–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailes, C. N. (2001). Integrative ASL-English language arts: Bridging paths to literacy. Sign Language Studies, 1(2), 147–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajarh, B. (2020). Teaching English as a second language through Indian sign language: An interventional study on interactive writing approach. IUP Journal of English Studies, 15(4), 116–129. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, D., & Hamilton, M. (1998). Local literacies: Reading and writing in one community. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Beach, K. D., McIntyre, E., Philippakos, Z. A., Mraz, M., Pilonieta, P., & Vintinner, J. P. (2018). Effects of a summer reading intervention on reading skills for low-income black and Hispanic students in elementary school. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 34(3), 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, E. B. (2010). Understanding advanced second-language reading (Paperback ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth, R. G., Dobkins, K. R., & Emmorey, K. (2021). Implicit activation of American sign language during English word recognition: Evidence from a Stroop interference task and event-related potentials. Brain and Language, 218, 104961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brentari, D., Fenlon, J., & Cormier, K. (2018). Sign language phonology. In Oxford research encyclopedia of linguistics. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, A. (2013). American sign language (ASL) literacy and ASL literature: A critical appraisal [Doctoral dissertation, York University]. Available online: https://yorkspace.library.yorku.ca/xmlui/handle/10315/31969 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Caldwell-Harris, C. L., & Hoffmeister, R. J. (2022). Learning a second language via print: On the logical necessity of a fluent first language. Frontiers in Communication, 7, 900399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, C., & Mayberry, R. I. (2000). Theorizing about the relationship between American sign language and reading. In C. Chamberlain, J. P. Morford, & R. I. Mayberry (Eds.), Language acquisition by eye (pp. 221–259). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Christie, J., & Wilkins, D. (1997). American sign language literature: Some considerations for legitimacy and quality issues. Sign Language Studies, 96, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M. D., Cue, K. R., Delgado, N. J., Greene-Woods, A. N., & Wolsey, J. L. A. (2020). Early intervention protocols: Proposing a default bimodal bilingual approach for deaf children. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24, 1339–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerc Center & California Department of Education. (2020). American sign language content standards. Gallaudet University. Available online: https://www.gallaudet.edu/clerc-center/asl-content-standards/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Copeland, S. R., & Keefe, E. B. (2007). Effective literacy instruction for students with moderate or severe disabilities. Brookes Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Di Perri, K. A. (2013). Bedrock literacy curriculum. Bedrock Literacy and Educational Services. Available online: http://www.bedrockliteracy.com (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Dostal, H. M., & Lederberg, A. R. (2020). The development and evaluation of literacy interventions for deaf and hard-of-hearing children. In S. Easterbrooks, & H. Dostal (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of deaf studies in literacy (pp. 401–416). Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostal, H. M., Wolbers, K. A., & Kilpatrick, J. R. (2019). The language zone: Differentiating writing instruction for students who are d/Deaf and hard of hearing. Writing & Pedagogy, 11(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhard, D. M., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (Eds.). (2025). Ethnologue: Languages of the world (28th ed.). SIL International. Available online: http://www.ethnologue.com (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Emmorey, K. (2002). Language, cognition, and the brain: Insights from sign language research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Enns, C., Hall, S., & Isaac, M. (2016). The impact of sign language on the vocabulary development of young deaf children. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 21(3), 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J. L., Perri, K. A. D., Howerton-Fox, A., & Jezik, C. (2020). Implications of a sight word intervention for deaf students. American Annals of the Deaf, 164(5), 592–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felton, R. H., & Wood, F. B. (1989). Cognitive deficits in reading disability and attention deficit disorder. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 22(1), 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, R., Dostal, H., Holcomb, L., & Henner, J. (2025). Science of reading: All doesn’t mean all. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. [Google Scholar]

- Gallaudet Research Institute. (2012). Regional and national summary report of data from the 2009–2010 annual survey of deaf and hard of hearing children and youth. GRI, Gallaudet University. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, J. P. (2015). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology in discourses (5th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Golos, D. B., & Moses, A. M. (2015). Supplementing an educational video series with video-related classroom activities and materials. Sign Language Studies, 15(2), 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, W. C. (2017). What you don’t know can hurt you: The risk of language deprivation by impairing sign language development in deaf children. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21(5), 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, W. C., Levin, L. L., & Anderson, M. L. (2017). Language deprivation syndrome: A possible neurodevelopmental disorder with sociocultural origins. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(6), 761–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, R. (2016). “Literacy”. In K. B. Jensen, E. Rothenbuhler, & R. Craig (Eds.), International encyclopedia of communication theory and philosophy. Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmeister, R. (2000). A piece of the puzzle: ASL and reading comprehension in deaf children. In C. Chamberlain, J. P. Morford, & R. I. Mayberry (Eds.), Language acquisition by eye (pp. 143–163). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmeister, R., & Caldwell-Harris, C. (2014). The importance of ASL to English literacy development for deaf children. Bilingual Research Journal, 37(1), 6–22. [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb, L., Dostal, H., & Wolbers, K. (2024). A comparative study of how teachers communicate in deaf education classrooms. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 30(1), 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmer, E., Heimann, M., & Rudner, M. (2017). Computerized sign language-based literacy training for deaf and hard-of-hearing children. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 22(4), 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrastinski, I., & Wilbur, R. B. (2016). Academic achievement of deaf and hard-of-hearing students in an ASL/English bilingual program. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 21(2), 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, T. (2013). Schooling in American sign language: A paradigm shift from a deficit model to a bilingual model in deaf education. Berkeley Review of Education, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Humphries, T., Kushalnagar, P., Mathur, G., Napoli, D. J., Padden, C., Pollard, R., & Smith, S. (2014). Language acquisition for deaf children: Reducing the harms of zero tolerance to the use of alternative approaches. Harm Reduction Journal, 11(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justice, L. M., Chow, S.-M., Capellini, C., Flanigan, K., & Colton, S. (2003). Emergent literacy intervention for vulnerable preschoolers. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 12(3), 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karkar Esperat, T. (2024, April 17). Multiliteracies in teacher education. In Oxford research encyclopedia of education. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katims, D. S. (1994). Emergence of literacy in preschool children with disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 17(1), 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keck, T., & Wolgemuth, K. (2020). American sign language phonological awareness and English reading abilities: Continuing to explore new relationships. Sign Language Studies, 20(2), 334–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefe, E. B., & Copeland, S. R. (2011). What is literacy? The power of a definition. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 36(3–4), 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliewer, C., Biklen, D., & Kasa-Hendrickson, C. (2006). Who may be literate? Disability and resistance to the cultural denial of competence. American Educational Research Journal, 43(2), 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klima, E. S., & Bellugi, U. (1979). The signs of language. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koppenhaver, D., Hendrix, M., & Williams, A. (2007). Toward evidence-based literacy interventions for children with severe and multiple disabilities. Seminars in Speech and Language, 28(1), 079–089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntze, M. (2004). The relationship between ASL narrative structure and English reading comprehension. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 9(3), 333–350. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntze, M. (2023). Explicating the relationship between ASL and English in text comprehension. American Annals of the Deaf, 167(5), 700–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurz, K. B., Schick, B., & Hauser, P. C. (2015). Deaf children’s science content learning in direct instruction versus interpreted instruction. Journal of Science Education for Students with Disabilities, 18(1), 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, F., & Harris, M. (2011). Longitudinal patterns of emerging literacy in beginning deaf and hearing readers. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 16(3), 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, H., Hoffmeister, R., & Bahan, B. (1996). A journey into the DEAF-WORLD. Dawn Sign Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, C. (1995). Sociolinguistics in deaf communities. Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Machalicek, W., Sanford, A., Lang, R., Rispoli, M., Molfenter, N., & Mbeseha, M. K. (2009). Literacy interventions for students with physical and developmental disabilities who use aided AAC devices: A systematic review. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 22(3), 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmor, G. S., & Petitto, L. (1979). Simultaneous communication in the classroom: How well is English grammar represented? Sign Language Studies, 23, 99–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschark, M., & Knoors, H. (2012). Educating deaf children: Language, cognition, and learning. Deafness & Education International, 14(3), 136–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D. S. (1993). Reasoning skills: A key to literacy for deaf learners. American Annals of the Deaf, 138(2), 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayberry, R. I., & Chamberlain, C. (2008). Cross-linguistic influences on the development of reading and writing. Available online: https://mayberrylab.ucsd.edu/papers/Chamberlain&Mayberry08.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Mayberry, R. I., & Eichen, E. B. (1991). The long-lasting advantage of learning sign language in childhood: Another look at the critical period for language acquisition. Journal of Memory and Language, 30(4), 486–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougal, E., Gracie, H., Oldridge, J., Stewart, T. M., Booth, J. N., & Rhodes, S. M. (2021). Relationships between cognition and literacy in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 40(1), 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuarrie, L., & Parrila, R. (2014). Literacy and linguistic development in bilingual deaf children: Implications of the “and” for phonological processing. American Annals of the Deaf, 159(4), 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirenda, P. (2003). Autism, literacy, and the promise of AAC. Topics in Language Disorders, 23(4), 233–252. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R. E., & Karchmer, M. A. (2004). Chasing the mythical ten percent: Parental hearing status of deaf and hard of hearing students in the United States. Sign Language Studies, 4(2), 138–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morford, J. P., Wilkinson, E., Villwock, A., Piñar, P., & Kroll, J. F. (2011). When deaf signers read English: Cross-language activation in deaf ASL-English bilinguals. Psychological Science, 22(5), 672–677. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. (1996). National science education standards. National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newport, E. L. (1990). Maturational constraints on language learning. Cognitive Science, 14(1), 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, K., Elwér, Å., Messer, D., & Danielsson, H. (2025). Cognitive and language abilities associated with reading in intellectual disability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Remedial and Special Education, 07419325251328644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nover, S. M. (2000). History of language planning in deaf education: The 19th century [Doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona]. ProQuest. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/91f210752f77fbef1419116d317c68b4/1?cbl=18750&diss=y&pq-origsite=gscholar (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Ormel, E., Giezen, M. R., Knoors, H., Verhoeven, L., & Gutierrez-Sigut, E. (2022). Predictors of word and text reading fluency of deaf children in bilingual deaf education programmes. Languages, 7(1), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papen, U., & Gillen, J. (2024). Peer to peer deaf multiliteracies: Experiential pedagogy, agency and inclusion in working with young adults in India. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 28(12), 2728–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, K. H. (2012). What is literacy? A critical overview of sociocultural perspectives. Journal of Language and Literacy Education, 8(1), 50–71. [Google Scholar]

- Petitto, L. A. (1987). On the autonomy of language and gesture: Evidence from the acquisition of personal pronouns in American sign language. Cognition, 27(1), 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfau, R., Steinbach, M., & Woll, B. (Eds.). (2012). Sign language: An international handbook. De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim, J., & Martinez, E. E. (2013). Defining literacy in the 21st century: A guide to terminology and skills. Texas Journal of Literacy Education, 1(1), 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Quer, J., & Cecchetto, C. (2020). The SIGN-HUB sign language atlas. SIGN-HUB Project. Available online: https://www.sign-hub.eu/atlas (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Rajendram, S. (2016). Translanguaging as an agentive pedagogy for multilingual learners: Affordances and constraints. International Journal of Multilingualism, 20(3), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudner, M., Andin, J., Rönnberg, J., Heimann, M., Hermansson, A., Nelson, K., & Tjus, T. (2015). Training literacy skills through sign language. Deafness & Education International, 17(1), 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, W., & Lillo-Martin, D. (2006). Sign language and linguistic universals. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, G. H., Lieberman, A. M., Emmorey, K., & Bosworth, R. G. (2024). Visual attention and cross-linguistic activation in deaf ASL–English bilingual readers: An eye-tracking study. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 28(1), 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. A., Dostal, H. M., & Lane-Outlaw, S. (2021). A call for diversity of perspective in deaf education research: A rejoinder to Mayer & Trezek (2020). American Annals of the Deaf, 166(1), 49–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scott, J. A., & Hansen, S. G. (2020). Comprehending science writing: The promise of dialogic reading for supporting upper elementary deaf students. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 41(2), 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simms, L., & Thumann, H. (2007). In search of a new, linguistically and culturally sensitive paradigm in deaf education. American Annals of the Deaf, 152(3), 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokoe, W. C. (1960). Sign language structure: An outline of the visual communication system of the American deaf (Studies in Linguistics, Occasional Papers, Vol. 8). University of Buffalo. [Google Scholar]

- Street, B. (1984). Literacy in theory and practice. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton-Spence, R., & Woll, B. (1999). The linguistics of British sign language: An introduction. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, H. L., Orosco, M. J., & Lussier, C. M. (2012). Cognition and literacy in English language learners at risk for reading disabilities. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(2), 302–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G., Li, Q., Li, J., & Yiu, C. K.-M. (2023). Chinese grammatical development of deaf and hard of hearing children in a sign bilingualism and co-enrollment program. American Annals of the Deaf, 167(5), 675–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tevenal, S., & Villanueva, M. (2009). Are you getting the message? The effects of simcom on the message received by deaf, hard of hearing, and hearing students. Sign Language Studies, 9(3), 266–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2017). Literacy in the 21st century: A global perspective. UNESCO Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ungureanu, E. (2024). Literacy as a social practice: Exploring teacher representations. Journal of Educational Sciences, 25(2), 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2023). World report on hearing: Promoting ear and hearing care across the life course. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240020481 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Villwock, A., Morford, J. P., & Kroll, J. F. (2021). Cross-linguistic activation in deaf bilingual children during English word recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 47(3), 435–449. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, S., & Hutchison, L. (2020). Using culturally relevant pedagogy to influence literacy achievement for Middle school black male students. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 64(4), 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., & Andrews, J. F. (2017). Literacy instruction in primary level deaf education in China. Deafness & Education International, 19(2), 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., & Andrews, J. F. (2021). Chinese Pinyin: Overview, history and use in language learning for young deaf and hard of hearing students in China. American Annals of the Deaf, 166(4), 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasik, B. A., Bond, M. A., & Hindman, A. (2006). The effects of a language and literacy intervention on head start children and teachers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbers, K. A., Dostal, H. M., Holcomb, L., & Spurgin, K. (2024). Developing expressive language skills of deaf students through specialized writing instruction. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 29(3), 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Federation of the Deaf. (2018). Sign languages: A global asset. WFD Position Paper. Available online: https://wfdeaf.org/news/resources (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Zernovoj, A. (2015). Video technology-mediated literacy practices in American Sign Language (ASL): A study of an innovative ASL/English bilingual approach to deaf education [Doctoral dissertation, University of California, San Diego]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Publication No. 3705462). [Google Scholar]

| Citation | Country of Participants | Literacy Area of Focus | Research Area/Goals/Aims | Number of Participants | Age of Participants | Participant Hearing Levels | Participant Languages Used | Analytic Approach | Results | Educational Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holmer et al. (2017) | Sweden | Reading | Whether computerized sign language-based literacy training improves reading skill in deaf signing children. | 16 (8 boys, 8 girls) | ~10.1 years | Not reported (participants attended educational program for the deaf) | Swedish Sign Language, Swedish | Hierarchical linear modeling, longitudinal cross-over design | Ability to imitate unfamiliar lexical signs predicted word reading; intervention showed weak support; suggests supramodal mechanism in word reading development | Reading skills, in particular word reading, are linked to sign language skills. |

| Kuntze (2023) | USA | Reading Comprehension | Whether ASL comprehension skills, English vocabulary paired with ASL inference skills, or age at enrollment at a bilingual school, home language, and/or quality of the home communication system predict ASL and English comprehension abilities. | 91 | Middle school aged | Not reported (participants attended educational program for the deaf) | ASL, Mexican Sign Language, Russian Sign Language, English | Multivariate analyses of variance, t-tests | Inferencing skills in ASL predict reading comprehension ability. Communication access at home adversely impacted reading skill. | Development of higher order thinking skills in ASL promotes reading comprehension. There is positive impact for instruction of higher order skills in ASL to promote engagement with text and literacy outcomes. |

| Ormel et al. (2022) | Netherlands | Reading fluency and decoding | How word and text reading accuracy and fluency are impacted by cognitive-linguistic ability in deaf children in bimodal-bilingual education programs. | 62 | 8–10 years | Severe to profound | Sign Language of the Netherlands, Dutch | Longitudinal predictive study with multiple regression analysis. | Fingerspelling ability and speech-based vocabulary strongly predict reading fluency; speech phonology affects word reading accuracy but not text fluency | Children use multimodal (manual and auditory/verbal) skills to address and develop reading skills in bilingual-bimodal educational contexts. More research is needed regarding specific signed and spoken contributors to literacy development. |

| Rudner et al. (2015) | Sweden | Reading | Whether the pilot, sign language version of the Omega-is literacy software (Omega-is-d1) impact literacy outcomes in classrooms where sign language is the primary mode of communication. | 12 | ~9:6 students in grades 1–2 (n = 6), students in grades 4–6 (n = 6) | Not reported | Swedish Sign Language, Swedish, European and non-European oral and signed languages, home sign systems | Small sample intervention study with pre/post assessment. ANOVA, repeated measures ANOVA. | Substantial literacy skill improvements over 20-day training period. Intervention effect indeterminate from regular classroom activities. | Literacy skills of deaf beginning readers improved substantially throughout this study. Future interventions for deaf beginning readers that utilize sign language as a component should extend the duration of training and fully implement salient practices related to multimedia interaction and recasting. |

| Scott and Hansen (2020) | USA | Reading comprehension | Whether dialogic reading is a successful intervention for deaf students to improve their comprehension of informational text | 1 | 11 years old, 5th grade | Participant had bilateral cochlear implants, indicating likely past severe hearing levels | American Sign Language, English | Multiple baselines, single case study design | Dialogic reading prompts for recall, identification of text features, and WH comprehension. No interpretable effect of distancing questions due to apparently spontaneous generalization of baseline skill. Evidence of carryover of dialogic reading skills between tiers of intervention despite staggered exposure of skills in intervention. | Dialogic reading may be a successful intervention for supporting comprehension of informational text with deaf students. Especially with the teaching of text structures to improve the accuracy of basic information recall. Author comment mentioned findings intended for students with severe-to-profound hearing levels. |

| Tang et al. (2023) | China | Writing | Whether deaf children’s exposure to Hong Kong Sign Language in a bilingual co-enrollment environment affect their development of the grammatical features of written Chinese. | 29 | ~7.1 years | Severe-to- profound hearing level | Hong Kong Sign Language, Spoken Cantonese, Written Mandarin Chinese | Multiple baselines longitudinal analysis using two-way ANOVA, one-way ANOVA, t-tests, post hoc Tukey tests. | Deaf students initially lagged behind their hearing peers but narrowed the developmental gap by year Primary 2 and caught up in most grammatical features and constructions by Primary 4. | Knowledge of grammar is an essential component supporting literacy skill development. More research is needed regarding whether enrollment in a Sign Language Co-Enrollment environment can support native-like competency in highly complex structures (e.g., relative clauses, location constructions) in written Chinese. |

| Wolbers et al. (2024) | USA | Writing | The extent to which the use of Strategic and Interactive Writing Instruction (SIWI) improves students’ use of genre-specific traits (across narrative, expository, and persuasive text) in expressive signed and written language. Whether there is a relationship between students’ use of genre-specific traits in expressive signed and written language. | 69 | Grades 3–6 | mild to severe hearing levels | American Sign Language, English. Languages spoken in students’ homes: Spanish, English, Urdu, Mandarin, Tagalog, Portuguese, Bengali | Quasi-experimental study with comparison group. Repeated measures ANOVA, Pearson correlation coefficients | Students in the treatment group made significant gains in expressive and written language for recount and information genres compared to the comparison group, with expressive language and writing positively correlated across all genres at both time points. | Literacy instruction that intentionally integrates expressive language learning with writing supports students’ overall writing and language growth. |

| Falk et al. (2020) | USA | Reading comprehension and fluency | Whether participation in the Bedrock sight word intervention program impacts the number of sight words or rate at which deaf students are able to read in isolation. | 30 | 6–12 years (grades 1–7) | Variable: moderate hearing levels (n = 1), severe hearing levels (n = 6), profound hearing levels (n = 22), could not test (n = 1) | American Sign Language, English. Author noted occasional Simultaneous Communication may have been included in educational program. | Parametric approach. Pretest/post-test design. Paired sample t-tests. | Significant increase in the number of words participants were able to identify from pretest to post-test. Significant increase in raw score performance on Test of Silent Word Reading Fluency (TOSWRF). Significant increases found for grade and age-equivalency scores. Pearson product-moment correlations indicated no significant correlation between TOSWRF performance and the age or grade level. Independent-samples t tests confirmed that neither home language nor gender were significant predictors of performance on the TOSWRF. | This study offers empirical evidence to support anecdotal reports of the Bedrock Literacy curriculum’s success with deaf students. Participants in this study demonstrated significant growth in the number of sight words they could read as well as in their fluency in reading familiar words. Unfortunately, the results also offered evidence that Deaf students have difficulty acquiring reading skills. |

| Citation | Country of Participants | Literacy Area of Focus | Research Area/Goals/Aims | Number of Participants | Age of Participants | Participant Hearing Levels | Participant Languages Used | Analytic Approach | Results | Educational Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bajarh (2020) | India | Writing | Whether the Interactive Writing approach—when mediated through Indian Sign Language—is effective in developing the written English skills of deaf students learning English as a second language. | 25 | 9th and 10th grade | Profound hearing loss | Indian Sign Language, written English, print language of dominant societal language for each participant | Narrative inquiry with statistical analysis of writing development. | Statistically significant improvement in writing parameters, better organization and content generation, improved attitude toward writing from students. Challenges with morphological structures, especially inflectional bound morphemes. | Use of sign language with the Interactive Writing approach could be effective with regard to improving both quantity and quality of deaf students’ writing. Specific gains when given contextually relevant, appropriate, structured and recursive writing support. |

| Dostal et al. (2019) | USA | Writing | Description of an evidence-based approach for engaging and supporting deaf students. Describes a framework that can be utilized to classify student language productions and scaffold them according to their level of clarity and fluency to support the strengthening of languaging. | 14 classes of students (exact number of students not reported) | Grades 3–5 | Not reported | American Sign Language, English | Discourse analysis and narrative description of classroom observations. | The Language Zone Flowchart provides a framework of support for recognizing and responding to student productions. The strategic use of this approach has the potential to support writing. | The current study presents the Language Zone Flowchart, an instructional tool that can be used to support teachers who aim to engage in developing writing and language skills of students. Use of this framework can support student engagement and strengthen the metalinguistic awareness of students. |

| Golos and Moses (2015) | USA | Early literacy skills | Whether children’s target vocabulary scores increase after viewing videos and participating in video related activities. Delineating the frequency and type of literacy-related behaviors that children demonstrate during video-related classroom activities. The nature of teacher perceptions about activity efficacy on student literacy learning. | 7 | 3–6 years | Hearing to profoundly deaf | American Sign Language, English | Grounded theory and narrative inquiry via a case study approach with video recording analysis and a teacher survey. | Children displayed targeted literacy skills during activities; descriptive statistics showed higher mean scores in targeted skills after activities | Findings indicate that supplemental media classroom activities can facilitate the learning of literacy skills and help children make connections between ASL and English print. This study offers new opportunities for the integration of early language exposure and curricular materials, and suggests a promising approach to developing key literacy and language skills with research-based media and media-related activities and materials |

| Holcomb et al. (2024) | USA | Writing | The way in which teachers navigate communication with deaf students who are emergent writers and lack language proficiency during language and writing instruction in grades 3–6, as well as the way in which communication differs between teachers who primarily use spoken English and those who primarily use ASL. | 9 | 8–13 years | Variable; moderately severe (n = 4), severe (n = 1) profound (n = 4) with variable use of hearing assistive technology. | American Sign Language, English | Narrative inquiry, classroom observation, analysis of language modalities and communication patterns. | ASL-using teachers employed more student-centered approaches with greater engagement and communication learning; spoken English-using teachers favored whole-class instruction with less individualized support | Despite the high quality of the teaching methods used in classrooms where teachers primarily used spoken language, students experienced decreased engagement which served as a barrier toward equal opportunities in their learning. Deaf emergent writers in classrooms where sign language support was inconsistent (e.g., settings that used SimCom) demonstrated less engagement as well. Teacher preparation programs and professional development must emphasize the skills necessary to engage all deaf students to ensure educational equity. |

| Papen and Gillen (2024) | India | Reading | Whether the use of peer-guided engagement with contextually appropriate multiliteracies encountered in the daily life of students can support their development of literacy skills. | 39 | 16–30 years | Not reported. Authors reported none of the participants or peer guides used hearing assistive technology. | Indian Sign Language, written English | Narrative inquiry, case study analysis across several peer-guided small group classes. Discussion of insights from pilot initiative using peer-guided literacy activities. | Students’ semiotic repertoire grew throughout the experience, and this contributed to their later contributions and written production. Inclusive educational approaches that utilize the benefits of peer-guided literacy maintain engagement and support carryover of skills across sessions. | This project shows the value of a deaf-led inclusive education where sign language and literacy are supported and developed, not used exclusively as a means to produce spoken language outcomes. Practitioners and policy-makers should seek to develop education opportunities for deaf people grounded in the value of diversity as a strength and building on deaf children and adults’ agency. |

| Wang and Andrews (2017) | China | Reading and writing | What methodologies are used to engage deaf students in literacy activities during classroom instruction. | 11 | Grades 1–2 | Not specifically mentioned, but classrooms included deaf students with hearing teachers. | Chinese Sign Language, spoken Chinese, spoken English. Authors also mentioned the use of Signed Chinese, Chinese character signs, Pinyin, and Pinyin Fingerspelling | Narrative inquiry, video analysis of classroom instruction. | Instruction followed the Gradual Release of Responsibility model with a focus on speech and hearing outcomes. The curriculum had lower academic expectations for deaf students than for their grade-matched hearing peers. | The content load of curriculum must be increased for deaf students to raise the academic performance expectations of these students. Deaf education programs would benefit from hiring more deaf teachers to provide appropriate language models. Use of storybooks can be adapted and implemented with deaf children to support background knowledge development. |

| Wang and Andrews (2021) | China | Reading | The extent and nature of the role Chinese Pinyin plays in deaf education classrooms, specifically during literacy instruction and the nature of its impact on deaf students’ literacy outcomes. | 11 | Grades 1–2 | Not listed. Authors stated students were deaf. | Chinese Sign Language, Chinese manual alphabet, Chinese finger syllabary, spoken and written Chinese. | Narrative inquiry with the use of transcribed discourse from video recordings in the classroom. | Pinyin serves different functions for deaf students versus hearing students. Visual and visuo-tactile approaches make phonological information accessible to deaf students, not necessarily mastery of Pinyin. | For DHH children, Pinyin does not serve as a phonological awareness enhancer, but teachers use it as a tool to teach language, both spoken and written Chinese. Pinyin instruction has been found to benefit hearing Chinese L2 learners. The increased use of hearing assistive technology may support student learning of Pinyin and Pinyin fingerspelling/Chinese manual alphabet as a tool to “bootstrap” the learning of spoken Chinese. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dostal, H.M.; Scott, J.A.; Chappell, M.D.; Black, C. A Scoping Review of Literacy Interventions Using Signed Languages for School-Age Deaf Students. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081104

Dostal HM, Scott JA, Chappell MD, Black C. A Scoping Review of Literacy Interventions Using Signed Languages for School-Age Deaf Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081104

Chicago/Turabian StyleDostal, Hannah M., Jessica A. Scott, Marissa D. Chappell, and Christopher Black. 2025. "A Scoping Review of Literacy Interventions Using Signed Languages for School-Age Deaf Students" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081104

APA StyleDostal, H. M., Scott, J. A., Chappell, M. D., & Black, C. (2025). A Scoping Review of Literacy Interventions Using Signed Languages for School-Age Deaf Students. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081104