The Relationship Between Men’s Self-Perceived Attractiveness and Ratings of Women’s Sexual Intent

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Men’s Overperception of Women’s Sexual Interest

1.2. Sexual Arousal and Overperception

1.3. The Potential Role of Men’s Attractiveness

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Power

3. Analysis Plan and Results

3.1. Physical Attractiveness Manipulation Check

3.2. Reliability

3.3. Direct Effect of the Attractiveness Manipulation

3.4. Assessment of Self-Reported Sexual Arousal

3.5. Primary Analyses

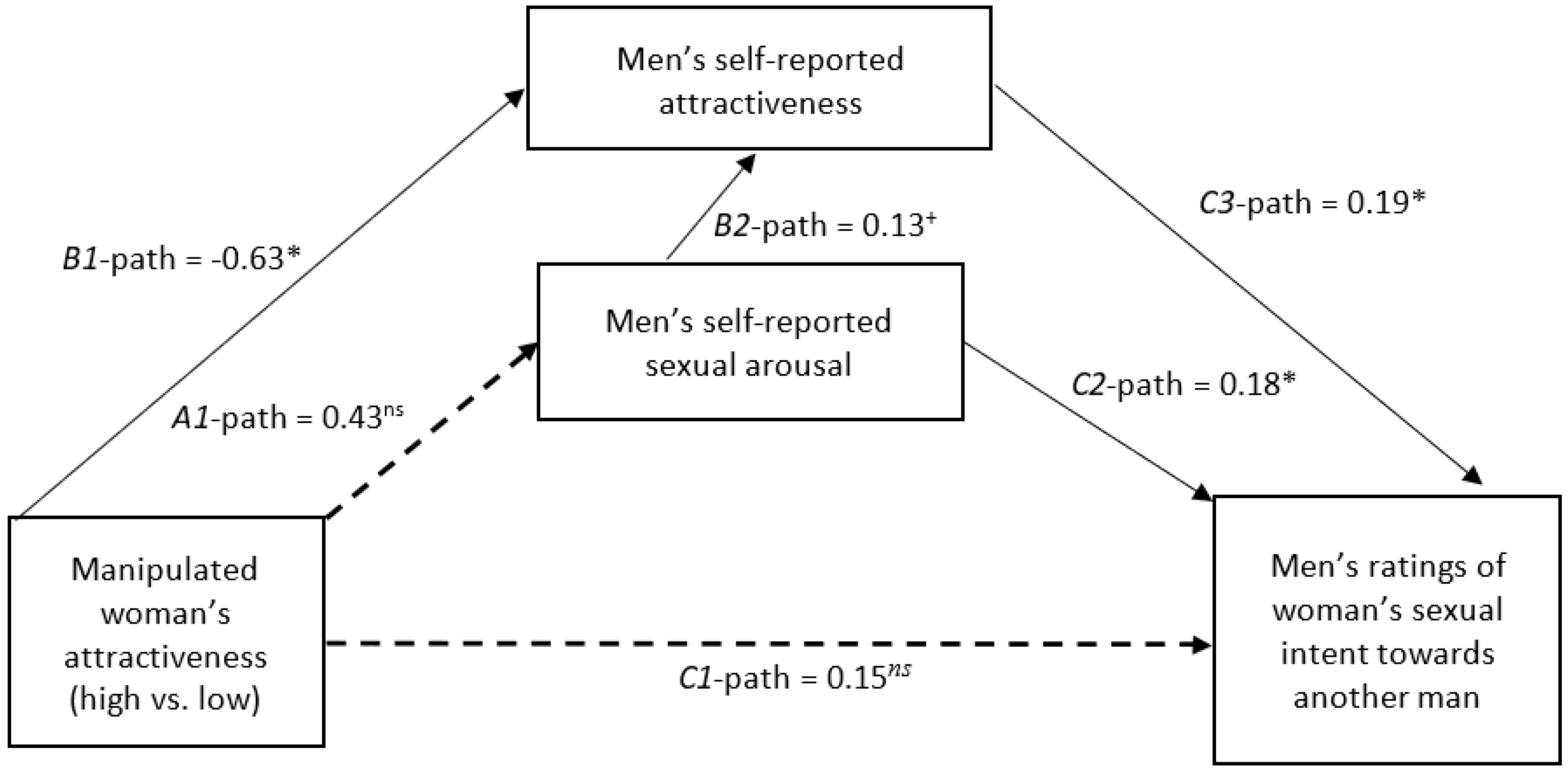

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SIP-Q | Sexual Intent Perceptions Questionnaire |

| 1 | According to the Chicago Face Database, the attractive photo was rated by 94 people who estimated the age of the woman was 23.96 years. Just over 97% of raters perceived the woman as White. The unattractive photo was rated by 99 people who estimated the age of the woman was 24.95 years. Over 98% of these raters perceived the woman as White. The attractive photo was received an attractiveness rating of 4.75/7. The unattractive photo received an attractiveness rating of 1.61/7. We informed participants the women were 21 years old to aid the impression they would be realistic romantic or sexual partners for the typical college aged male. |

| 2 | The attractiveness manipulation is dummy coded using the unattractive condition as the reference group, so positive betas mean a given dependent variable is higher for the attractive face compared to the unattractive face. |

| 3 | Even without a significant direct effect, a significant indirect is possible and would indicate a mediated effect (See Zhao et al. (2010) for a nontechnical discussion, but see (Kenny et al., 1998; MacKinnon & Fairchild, 2009) for more technical discussions). |

References

- Abbey, A. (1982). Sex differences in attributions for friendly behavior: Do males misperceive females’ friendliness? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(5), 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbey, A., Cozzarelli, C., McLaughlin, K., & Harnish, R. J. (1987). The effects of clothing and dyad sex composition on perceptions of sexual intent: Do women and men evaluate these cues differently. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 17(2), 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicke, M. D., & Sedikides, C. (2009). Self-enhancement and self-protection: What they are and what they do. European Review of Social Psychology, 20(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariely, D., & Loewenstein, G. (2006). The heat of the moment: The effect of sexual arousal on sexual decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 19(2), 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berscheid, E., Dion, K., Walster, E., & Walster, G. W. (1971). Physical attractiveness and dating choice: A test of the matching hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 7(2), 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S., & Loewenstein, G. (2022). Drive states. In R. Biswas-Diener, & E. Diener (Eds.), Noba textbook series: Psychology. DEF Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bouffard, J. A., & Miller, H. A. (2014). The role of sexual arousal and overperception of sexual intent within the decision to engage in sexual coercion. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(11), 1967–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouffard, J. A., & Miller, H. A. (2024). Misperceptions of sexual intent in women: Exploring possible correlates and their relationships with sexual coercion compared to men. Victims & Offenders, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W., & Lewis, S. A. (1968). Dating and physical attractiveness: Replication. Psychological Reports, 22(3), 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, D. M. (2006). Strategies of human mating. Psychological Topics, 15(2), 239–260. [Google Scholar]

- Buss, D. M. (2017). Sexual conflict in human mating. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(4), 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, D. M., & Shackelford, T. K. (2008). Attractive women want it all: Good genes, economic investment, parenting proclivities, and emotional commitment. Evolutionary Psychology, 6, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T. F., Dawson, K., Davis, P., Bowen, M., & Galumbeck, C. (1989). Effects of cosmetics use on the physical attractiveness and body image of American college women. The Journal of Social Psychology, 129(3), 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T. F., & Derlega, V. J. (1978). The matching hypothesis: Physical attractiveness among same-sexed friends. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 4(2), 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloud, J. M., & Perilloux, C. (2022). The relationship between mating context and women’s appearance enhancement strategies. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 16(2), 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dion, K., Berscheid, E., & Walster, E. (1972). What is beautiful is good. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24(3), 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ditto, P. H., Pizarro, D. A., Epstein, E. B., Jacobson, J. A., & MacDonald, T. K. (2006). Visceral influences on risk-taking behavior. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 19(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, D. J. (2012). Marking sexuality from 0–6: The Kinsey scale in online culture. Sexuality & Culture, 16(3), 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edlund, J. E., & Sagarin, B. J. (2014). The mate value scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 64, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdfelder, E., Faul, F., & Buchner, A. (1996). GPOWER: A general power analysis program. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers, 28(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farris, C., Treat, T. A., Viken, R. J., & McFall, R. M. (2008). Sexual coercion and the misperception of sexual intent. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(1), 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherstone, L., Byrnes, C., Maturi, J., Minto, K., Mickelburgh, R., & Donaghy, P. (2024). What is affirmative consent? In D. Cowan (Ed.), The limits of consent: Sexual assault and affirmative consent (pp. 23–40). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkes, V. S. (1982). Forming relationships and the matching hypothesis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 8(4), 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galupo, M. P., Mitchell, R. C., Grynkiewicz, A. L., & Davis, K. S. (2014). Sexual minority reflections on the kinsey scale and the Klein sexual orientation grid: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Bisexuality, 14(3–4), 404–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, J. P., Wheeler, L., & Suls, J. (2018). A social comparison theory meta-analysis 60+ years on. Psychological Bulletin, 144(2), 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselton, M. G. (2003). The sexual overperception bias: Evidence of a systematic bias in men from a survey of naturally occurring events. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(1), 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselton, M. G. (2007). Error management theory. In R. F. Baumeister, & K. D. Vohs (Eds.), Encyclopedia of social psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 311–312). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Haselton, M. G., & Buss, D. M. (2000). Error management theory: A new perspective on biases in cross-sex mind reading. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(1), 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselton, M. G., & Buss, D. M. (2009). Error management theory and the evolution of misbeliefs. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 32(6), 522–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselton, M. G., & Gildersleeve, K. (2011). Can men detect ovulation? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(2), 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, S. E., & Muehlenhard, C. L. (1999). “By the semi-mystical appearance of a condom”: How young women and men communicate sexual consent in heterosexual situations. The Journal of Sex Research, 36(3), 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E. E., & Nisbett, R. E. (1972). The actor and the observer: Divergent perceptions of the causes of behavior. In E. E. Jones, D. Kanouse, H. H. Kelley, R. E. Nisbett, S. Valins, & B. Weiner (Eds.), Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior (pp. 79–94). General Learning Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kalick, S. M., & Hamilton, T. E. (1986). The matching hypothesis reexamined. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(4), 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Bolger, N. (1998). Data analysis in social psychology. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed., Vols. 1–2, pp. 233–265). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. W. B. Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Koukounas, E., & Letch, N. M. (2001). Psychological correlates of perception of sexual intent in women. The Journal of Social Psychology, 141(4), 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, T. N., & Davis, D. (2020). Power affects perceptions of sexual willingness: Implications for litigating sexual assault allegations. Violence and Gender, 7(3), 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, T. N., & Rerick, P. O. (2023). Men’s physical attractiveness predicts women’s ratings of sexual intent through sexual arousal: Implications for sexual (mis)communication. Sexes, 4, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, T. N., Rerick, P. O., & Davis, D. (2022). Relationships between sexual arousal, relationship status, and men’s ratings of women’s sexual willingness: Implications for research and practice. Violence and Gender, 9(23), 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, G. (1996). Out of control: Visceral influences on behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 65(3), 272–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D. S., Correll, J., & Wittenbrink, B. (2015). The Chicago face database: A free stimulus set of faces and norming data. Behavior Research Methods, 47(4), 1122–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D. P., & Fairchild, A. J. (2009). Current directions in mediation analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(1), 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maner, J. K., Kenrick, D. T., Becker, D. V., Robertson, T. E., Hofer, B., Neuberg, S. L., Delton, A. W., Butner, J., & Schaller, M. (2005). Functional projection: How fundamental social motives can bias interpersonal perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(1), 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, N. B. (1979). Come-ons and put-offs: Unmarried students’ strategies for having and avoiding sexual intercourse. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 4(12), 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C. L., & Peterson, R. D. (2021). Physical attractiveness, halo effects, and social joining. Social Science Quarterly, 102(1), 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S., & Kim, S.-H. (2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis of bystander intervention programs for intimate partner violence and sexual assault. Psychology of Violence, 13(2), 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perilloux, C., Easton, J. A., & Buss, D. M. (2012). The misperception of sexual interest. Psychological Science, 23(2), 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posit Team. (2025). RStudio: Integrated development environment for R. Posit Software, PBC. Available online: http://www.posit.co/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Prokop, P., & Pazda, A. D. (2016). Women’s red clothing can increase mate-guarding from their male partner. Personality and Individual Differences, 98, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rerick, P. O., & Livingston, T. N. (2022). Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and so is intent: Men’s interpretations of the sexual intent of attractive versus unattractive women. Violence and Gender, 9(4), 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rerick, P. O., Livingston, T. N., & Davis, D. (2020). Does the horny man think women want him too? Effects of male sexual arousal on perceptions of female sexual willingness. The Journal of Social Psychology, 160(4), 520–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rerick, P. O., Livingston, T. N., & Davis, D. (2022). Let’s just do it: Sexual arousal’s effects on attitudes regarding sexual consent. The Journal of Social Psychology, 164(4), 456–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, G., Simmons, L. W., & Peters, M. (2005). Attractiveness and sexual behavior: Does attractiveness enhance mating success? Evolution and Human Behavior, 26(2), 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, J., Brauer, J. R., & Ellonen, N. (2020). Beauty is in the eye of the offender: Physical attractiveness and adolescent victimization. Journal of Criminal Justice, 66, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, D. P., & Buss, D. M. (1996). Strategic self-promotion and competitor derogation: Sex and context effects on the perceived effectiveness of mate attraction tactics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(6), 1185–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumlich, E. J., & Fisher, W. A. (2020). An exploration of factors that influence enactment of affirmative consent behaviors. The Journal of Sex Research, 57(9), 1108–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephan, W., Berscheid, E., & Walster, E. (1971). Sexual arousal and heterosexual perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 20(1), 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Taylor, L. S., Fiore, A. T., Mendelsohn, G. A., & Cheshire, C. (2011). “Out of my league”: A real-world test of the matching hypothesis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(7), 942–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, T. J., Fisher, M. L., Salmon, C., & Downs, C. (2021). Want to hookup?: Sex differences in short-term mate attraction tactics. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 7(4), 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zell, E., Strickhouser, J. E., Sedikides, C., & Alicke, M. D. (2020). The better-than-average effect in comparative self-evaluation: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146(2), 118–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., Jr., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Instructions: Imagine that Megan engaged in each of these behaviors with a man [you]. Then, indicate how likely it is that this behavior means Megan wants to have sex with that man [you]. | ||||

| Item (She…) | Ratings with Other Man as Target | Ratings with Self as Target | ||

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| …drinks with a man she just met | 2.13 | 1.36 | 1.88 | 1.34 |

| …becomes intoxicated with alcohol on a date with a man she has not met before | 2.45 | 1.62 | 2.04 | 1.56 |

| …becomes intoxicated with alcohol at a party without a date | 2.14 | 1.51 | 1.77 | 1.45 |

| …becomes intoxicated with alcohol at a party and leaves the party with a man she just met | 3.65 | 2.18 | 2.88 | 1.99 |

| …goes out to lunch with a man | 2.06 | 1.35 | 2.19 | 1.48 |

| …approaches a man to initiate conversation | 2.09 | 1.24 | 2.17 | 1.53 |

| …sits or stands close to a man | 1.92 | 1.14 | 2.26 | 1.54 |

| …gives a man her phone number | 2.91 | 1.50 | 2.92 | 1.62 |

| …wears perfume | 2.26 | 1.53 | 2.27 | 1.50 |

| …acts very affectionate toward a man at a party | 4.14 | 1.70 | 3.80 | 1.71 |

| …tells a man how great he looks | 3.03 | 1.48 | 2.93 | 1.72 |

| …invites a man to her house for dinner | 3.40 | 1.78 | 3.32 | 1.87 |

| …Leans up Against him | 3.54 | 1.76 | 3.88 | 1.81 |

| …Lets a man perform oral | 5.82 | 1.77 | 6.01 | 1.47 |

| …Let’s a man touch her breasts through her clothes | 5.63 | 1.68 | 5.90 | 1.46 |

| …takes of shirt and bra around a man | 5.22 | 1.92 | 5.43 | 1.70 |

| …goes to a man’s residence during a date to be alone | 4.53 | 1.98 | 4.20 | 2.01 |

| …dresses very sexily | 4.04 | 2.21 | 3.70 | 2.07 |

| …touches a man’s bare genitals | 5.90 | 1.633 | 6.22 | 1.21 |

| …takes off her pants, skirt and underwear | 5.69 | 1.78 | 5.88 | 1.57 |

| …spends the night at a man’s residence | 4.17 | 2.03 | 3.90 | 1.90 |

| …doesn’t resist when man initiates intercourse | 4.95 | 1.92 | 5.17 | 1.84 |

| …sends nude pictures | 5.17 | 1.72 | 5.55 | 1.56 |

| …says yes to an invitation to watch a movie at a man’s residence | 3.40 | 1.80 | 3.36 | 1.94 |

| …uses marijuana on a date with a man she has not had sex with before | 2.38 | 1.60 | 2.16 | 1.51 |

| Overall M and SD | 3.67 | 1.24 | 3.71 | 1.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rerick, P.O.; Livingston, T.N.; Singer, J. The Relationship Between Men’s Self-Perceived Attractiveness and Ratings of Women’s Sexual Intent. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081101

Rerick PO, Livingston TN, Singer J. The Relationship Between Men’s Self-Perceived Attractiveness and Ratings of Women’s Sexual Intent. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081101

Chicago/Turabian StyleRerick, Peter O., Tyler N. Livingston, and Jonathan Singer. 2025. "The Relationship Between Men’s Self-Perceived Attractiveness and Ratings of Women’s Sexual Intent" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081101

APA StyleRerick, P. O., Livingston, T. N., & Singer, J. (2025). The Relationship Between Men’s Self-Perceived Attractiveness and Ratings of Women’s Sexual Intent. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081101