Examining the Structure of Directed Motivational Currents (DMCs) Among Secondary and Tertiary English as a Second Language Learners

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

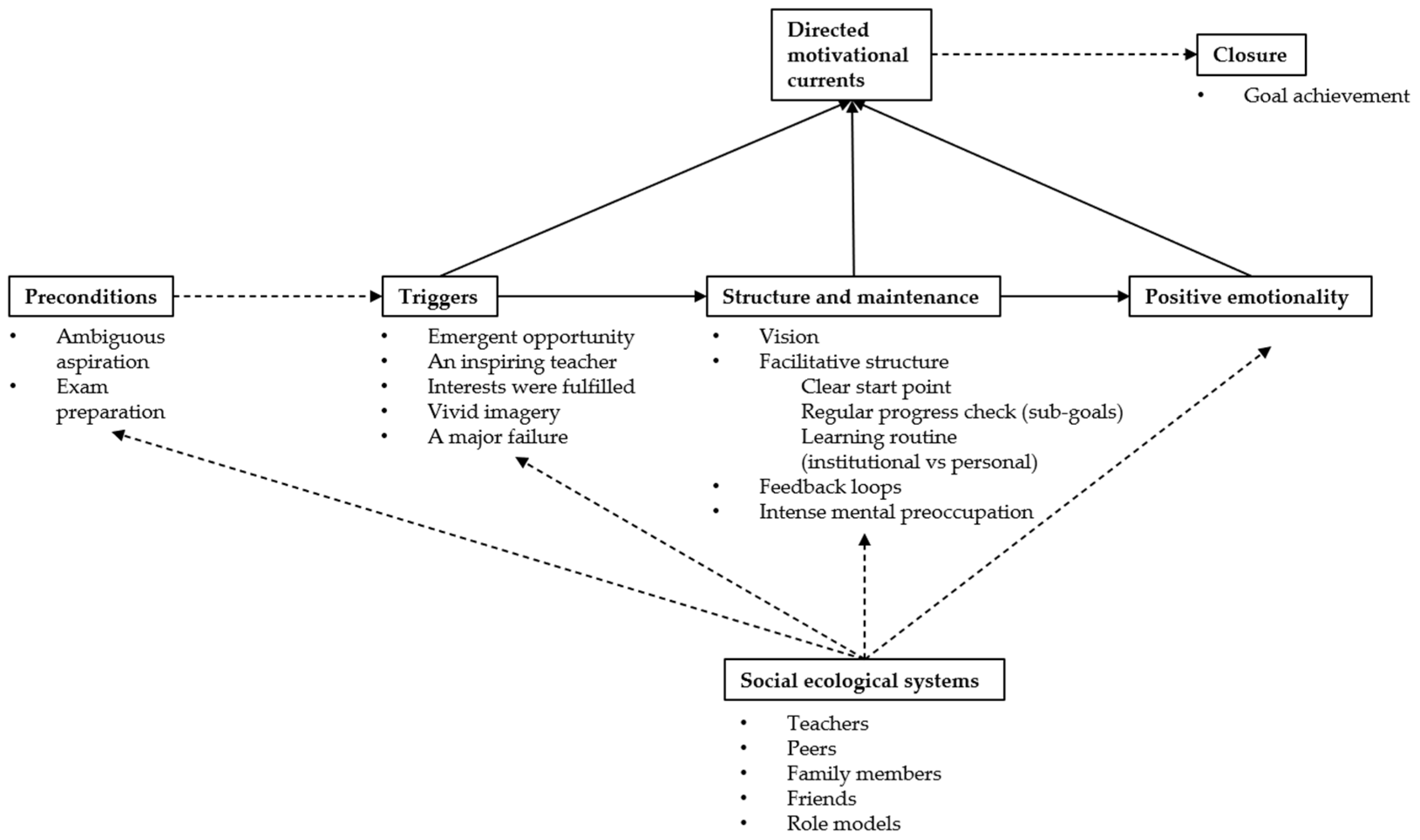

2.1. Key Components of Directed Motivational Currents (DMCs)

2.2. Flow Theory

2.3. Goal-Setting Theory and Expectancy-Value Theory

2.4. Empirical Studies

- (1)

- What criteria are considered when adopting a DMC structure?

- (2)

- In what ways does a DMC structure sustain motivation throughout its course?

- (3)

- Are there any non-defining features of the DMC framework?

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Procedure and Interview Schedule

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Mapping DMC Progression from Trigger to Trajectory

4.2. Theme 1: The DMC Launch

4.2.1. Pre-Conditions for DMC

4.2.2. Clear Starting Point and DMC Triggers

4.2.3. The DMC Triggers

When I heard this program, my ambition sparked. To be one of this elite group and to attend the best high school became a fervent desire within me. Consequently, I started to take English study seriously which I previously overlooked.

When I entered junior high school, my new English teacher organized the classes in a manner that captivated our interest, designing a variety of activities that encouraged interaction both between teacher and students, and among the students themselves, which let him create an immersive English-speaking environment, compelling us to communicate in English…

…my English teacher often told stories of her university life which was vivid and captivated…

I was so happy to major in interpretation and international trade. Upon my first arrival on campus, everything felt fresh and exhilarating. Motivated by this new beginning, I committed to diligently studying English, aiming to secure a position at international companies in the future.

Both my family and I were deeply disappointed by my result. I never anticipated that I was rejected by all the universities that I had applied. Particularly, when I saw most of my classmates enrolled in the universities, I felt an intensified sense of shame, anger, fear and resentment towards myself. However, I was not ready to concede to defeat. I swore to study hard, determined to reattempt the exam next year. I became so focused on my preparations that it felt as if I had isolated myself from the outside world, dedicating countless days and nights to studying in the classroom, avoiding all kinds of entertainment.

4.3. Theme 2: Developing a DMC Structure

4.3.1. Invest in Extra Time

… I first realized that I needed to devote more time and effort to my English study. I used to take naps at noon, but I quit it and would head straight back to classroom after lunch. Moreover, I extended my study hours until midnight.

4.3.2. Urge to Develop a DMC Structure

…though I managed to adhere to the schedule aligned with our monthly exams, I realized it was insufficient. I envisioned a new schedule in my mind, one that could accommodate my learning needs, amplify my strengths and addressing my weaknesses.

4.3.3. Institutionalized Structure vs. New Learning Structure

… school classes were important, yet the memorization techniques my teacher employed were not effective for me. The best way for me to retain vocabulary was to incorporate these words into my daily life. Typically, the English teacher would highlight key words on the blackboard, and I would select those I found challenging. Lacking an English-speaking environment, I resorted to crafting stories or dialogues and engaging in solo role-play.

4.3.4. Criteria Used in Selecting a DMC Structure

4.4. Theme 3: DMC Structure and Maintaining Motivation

4.4.1. Developing Behavioral Routines

I attended one or two English classes daily, where our teacher focused on exam preparation … my own routine went like: I woke up 30 min early every morning to listen to English news or dialogues…

…Upon entering university, my schedule was no longer as tight. My focus shifted solely to improving my English. I resorted to using task lists and timer apps on my phone to keep track of the goals I set for myself. Completing these tasks daily brought me immense pleasure and a profound sense of satisfaction.

4.4.2. Adjustment of a DMC Routine

During a simulated international business interpretation assignment, I learned to use PowerPoint to showcase our products. This opportunity was a novel experience for me. It was exhilarating to engage with learning material outside of textbooks. From that point on, I created and shared several slides with my peers every week.

4.4.3. Intense Mental/Affective Preoccupation

4.4.4. Manageable Subgoals

… I began incorporating additional vocabulary from news sources into my word list and engaged in solo role-play exercises to practice these new words and phrases.

…Then, I adopted a two-step strategy. Initially, I enrolled in an off-campus institution’s summer camp focused on IELTS exam preparation. The second phase involved crafting my individual plan, incorporating diverse learning resources from both the institution and online platforms. I set specific subgoals, such as passing the CET4 and CET6 exams, and devised detailed plans targeting vocabulary, grammar, speaking, listening, and reading skills.

4.4.5. Feedback Loops

I eagerly anticipated my teacher’s feedback on each of my assignments or exam papers. Whether it was corrections of my mistakes or praise for my progress, both were vital to me, providing benchmarks to evaluate my improvement. Additionally, whenever I raised my hand and answered questions in English in front of my class, I looked forward to my teacher’s commendation, or even just a smile or nod, as encouragement.

4.5. Theme 4: DMC Closure

Patterns of DMC Closure

The methods that worked for my university entrance examination proved ineffective for my current university studies…the nature of the challenges I now face has changed. University life is more flexible, presenting numerous distractions. The lack of external pressure and clear direction is notable… In the absence of exams, I struggle to gauge my English proficiency, particularly my speaking skills.

I am aware that university is full of distractions, making it challenging to adhere strictly to the methods I used in high school. While I continue to attend classes and visit the library daily, I no longer depend solely on my teachers or focus my efforts around exam preparation.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Individual DMCs Interview Procedures and Protocol

- -

- What made this dramatic change to happen? The main reasons and factors that made this get started. Discuss the circumstances that led to that journey.

- -

- What was your goal?

- -

- How was your motivation during this period toward learning L2?

- -

- Was your motivation qualitatively and/or quantitatively different during this period in comparison to before and after?

- -

- Did you feel something different going on in your life during that period? Why?

- -

- When you reflect back on that experience, what comes to your mind and what do you miss about it?

- -

- Did you achieve your goal? How long did it continue?

- -

- What was your feeling during that period?

- -

- Was your goal personally important? Why?

- -

- Did you also envision receiving your goal (imagining the moment of getting your goal)?

- -

- In addition to your final goal, how did you set your immediate or shorter-term goals?

- -

- What plan/mechanisms/resources did you use? Did doing this become a daily routine?

- -

- Discuss your daily life in regard to your engagement in improving your language during this time?

- -

- Did you take a course or was it based on a personalized learning plan?

- -

- How did you measure your progress?

- -

- Did you attempt to receive guidance from others, for example from a teacher or a more competent peer?

- -

- Did you break your goals into short and long-term goals? How? Why?

- -

- How long were you studying during this time? Discuss your daily engagement with L2 learning.

- -

- How long did it last for?

- -

- Did you feel happy during that period? Why?

- -

- Did you feel excited? What was it that you were excited about?

- -

- Did you not try to share your excitement and happiness with other people? Why/Why not?

- -

- How was the quality of time spent on learning/improving language in that experience?

- -

- Did you enjoy effort? Or was it felt like a burden? Did you even enjoy the difficulties? Why?

- -

- Did this experience bring meaning to your life at that time? Why?

- -

- Did other people tell you or think you were making a big deal of this experience?

- -

- In what way did this engagement develop your potential?

- -

- In what way, did it make you a better, more skillful person?

- -

- During that period, how important this had become in your life? Was it important or not so important?

- -

- How being successful in this experience give you the sense of discovering your potential?

- -

- Were you concerned/upset that this period and experience was finally over?

- -

- Have you tried to repeat the same experience? Have you been successful? Why/Why not?

References

- Başöz, T., & Gümüş, Ö. (2022). Directed motivational currents in L2: A focus on triggering factors, initial conditions, and (non)defining features. System, 104, 102920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P., & Zhang, J. (2020). 大学生英语听力定向性动机流的微变化研究 [Idiodynamic research into EFL listeners’ directed motivational currents]. Modern Foreign Languages, 43(2), 200–212. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/44.1165.h.20200109.1114.010.html (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Chang, P., & Zhou, L. (2023). Pinpointing the pivotal mediating forces of directed motivational currents (DMCs): Evidence from the Q methodology. System, 117, 103095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, S. (2024). What motivates Chinese students to study in the UK? A fresh perspective through a “small-lens”. Higher Education, 88(7), 1589–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety: The experience of play in work and games. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1988). The flow experience and its significance for human psychology. In M. Csikszentmihalyi, & I. S. Csikszentmihalyi (Eds.), Optimal experience: Psychological studies of flow in consciousness (pp. 15–35). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N. K. (2017). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z., & Chan, L. (2013). Motivation and vision: An analysis of future L2 self images, sensory styles, and imagery capacity across two target languages. Language Learning, 63(3), 437–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z., Henry, A., & Muir, C. (2015). Motivational currents in language learning: Frameworks for focused interventions. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z., Ibrahim, Z., & Muir, C. (2016). ‘Directed motivational currents’: Regulating complex dynamic systems through motivational surges. In Z. Dörnyei, P. D. MacIntyre, & A. Henry (Eds.), Motivational dynamics in language learning (pp. 95–105). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z., & Muir, C. (2019). Creating a motivating classroom environment. In X. Gao (Ed.), Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 719–736). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z., Muir, C., & Ibrahim, Z. (2014). Directed motivational currents: Energising language learning through creating intense motivational pathways. In D. Lasagabaster, A. Doiz, & J. M. Sierra (Eds.), Motivation and foreign language learning: Teaching from theory to practice (pp. 9–29). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z., & Ryan, S. (2015). The psychology of the language learner revisited. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2011). Teaching and researching motivation (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erten, I. H., & Selcuk, Ö. (2017). A display of patterns of change in learners’ motivation: Dynamics perspective. Novitas-ROYAL (Research on Youth and Language), 11(2), 128–141. [Google Scholar]

- García-Pinar, A. (2022). Group directed motivational currents: Transporting undergraduates toward highly valued end goals. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 30(1), 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspard, H., Häfner, I., Parrisius, C., Trautwein, U., & Nagengast, B. (2017). Assessing task values in five subjects during secondary school: Measurement structure and mean level differences across grade level, gender, and academic subject. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 48, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanizadeh, A., & Jahedizadeh, S. (2017). Directed motivational currents: The implementation of the dynamic web-based Persian scale among Iranian EFL learners. Teaching English as a Second Language Quarterly (Formerly Journal of Teaching Language Skills), 36(1), 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüş, Ö. (2019). Exploring directed motivational currents of English as a foreign language learners at the tertiary level through the dynamic systems perspective [Doctoral dissertation, Hacettepe University]. [Google Scholar]

- Gümüş, Ö., & Muir, C. (2020). Directed motivational currents: An agenda for future research. Eurasian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 6(3), 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, A., Davydenko, S., & Dörnyei, Z. (2015). The anatomy of directed motivational currents: Exploring intense and enduring periods of L2 motivation. The Modern Language Journal, 99(2), 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, C., Stephens, J. M., & Zhang, L. J. (2025). The prevalence and predictors of directed motivational currents among secondary and tertiary L2 English learners in China [Manuscript submitted for publication].

- Ibrahim, Z. (2016a). Affect in directed motivational currents: Positive emotionality in long-term L2 engagement. In P. D. MacIntyre, T. Gregersen, & S. Mercer (Eds.), Positive psychology in SLA (pp. 258–281). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Z. (2016b). Directed motivational currents: Optimal productivity and long-term sustainability in second language acquisition [Doctoral dissertation, University of Nottingham]. Available online: https://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/33489/ (accessed on 8 November 2019).

- Li, C., Tang, L., & Zhang, S. (2021). Understanding directed motivational currents among Chinese EFL students at a technological university. International Journal of Instruction, 14(2), 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting & task performance. Prentice-Hall, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Muir, C. (2016). The dynamics of intense long-term motivation in language learning: Directed motivational currents in theory and practice [Doctoral dissertation, University of Nottingham]. Available online: https://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/33810/ (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Muir, C. (2020). Directed motivational currents and language education: Exploring implications for pedagogy (Vol. 8). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Muir, C., & Dörnyei, Z. (2013). Directed motivational currents: Using vision to create effective motivational pathways. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 3(3), 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, C. (2021). Using expectancy-value theory to understand motivation, persistence, and achievement in university-level foreign language learning. Foreign Language Annals, 54, 1238–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S., & Kim, T.-Y. (2024). A qualitative approach to Korean EFL students’ L2 motivation and directed motivational currents. Lanaguage Research, 60(2), 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietluch, A. (2018). Extraordinary motivation or a high sense of personal agency: The role of self-efficacy in the directed motivational currents theory. New Horizons in English Studies, 3(1), 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdari, S., & Maftoo, P. (2017). The rise and fall of directed motivational currents: A case study. The Journal of Language Learning and Teaching, 7(1), 43–54. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/jltl/issue/42178/507809 (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Shen, B., Lin, Z., & Xing, W. (2025). Chinese English-as-a-foreign-language learners’ directed motivational currents for high-stakes English exam preparation. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 35(1), 436–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, A. S. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: A eudaimonist’s perspective. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(4), 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xodabande, I., & Babaii, E. (2021). Directed motivational currents (DMCs) in self-directed language learning: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Language and Education, 7(3), 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazawa, O. (2020). Directed motivational currents and their triggers in formal English learning educational settings in Japan. Gakuen, 953, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S., & Liu, H. (2023). Longitudinal detection of directed motivational currents in L2 learning: Motivated behaviours and emotional responses. Current Psychology. Advanced online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrinabadi, N., & Khajeh, F. (2021). Describing characteristics of group-level directed motivational currents in EFL contexts. Current Psychology. Advanced online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrinabadi, N., & Khodarahmi, E. (2023). Investigating the consequences of experiencing directed motivational currents for learners’ beliefs and self-perceptions. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 44(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrinabadi, N., & Soleimani, M. (2022). Directed motivational currents in second language: Investigating the effects of positive and negative feedback on energy investment and goal commitment. TESOL Quarterly, 56(4), 1281–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrinabadi, N., & Tavakoli, M. (2017). Exploring motivational surges among Iranian EFL teacher trainees: Directed motivational currents in focus. TESOL Quarterly, 51(1), 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant | Pre-Trigger Goal | Post-Trigger Goal |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Chen | To enter a high school and study in a competitive environment. | To gain high scores in English and enter a target high school. |

| 2. Yan | To gain an opportunity to enroll in a prestigious university. | To gain high scores in English which is his weak point. |

| 3. Sun | To further her study overseas, broaden her horizon and prepare her for the future competitive work market. | To improve her English and pass IELTS examination. |

| 4. Qin | No specific goal was mentioned. | To improve her English proficiency and gain high scores. |

| 5. Hu | To catch up with others and enter a prestigious university. | To gain high scores in English which is his weak point. |

| 6. Dou | To secure a bright future life and prove himself to relatives. | To gain high scores in English and pass exam. |

| 7. Wang | To enter best high school and best university, to be an elite in the society. | To seek every source benefiting his math and English advancement. |

| 8. Kiki | To be an interpreter and to do international business. | To study English diligently on interpretation. |

| 9. Du | To enhance her English skills, enabling her to live freely in a foreign country. | Stick to the plan arranged by App to keep learning English. |

| 10. Ya | To gain admission to top-tier universities for her graduate study. | To improve her English and pass IELTS examination. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huo, C.; Zhang, L.J.; Stephens, J.M. Examining the Structure of Directed Motivational Currents (DMCs) Among Secondary and Tertiary English as a Second Language Learners. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081066

Huo C, Zhang LJ, Stephens JM. Examining the Structure of Directed Motivational Currents (DMCs) Among Secondary and Tertiary English as a Second Language Learners. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081066

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuo, Chuanwei, Lawrence Jun Zhang, and Jason M. Stephens. 2025. "Examining the Structure of Directed Motivational Currents (DMCs) Among Secondary and Tertiary English as a Second Language Learners" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081066

APA StyleHuo, C., Zhang, L. J., & Stephens, J. M. (2025). Examining the Structure of Directed Motivational Currents (DMCs) Among Secondary and Tertiary English as a Second Language Learners. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081066