1. Introduction

The “lying flat” phenomenon is particularly prevalent among younger generations in China, including millennials and Generation Z, who are grappling with the pressures of navigating an increasingly competitive job market and societal expectations (

Ou, 2023). Literally, “lying flat” refers to a person lying flat on his or her back, with the whole body relaxed, making no movement and responding to nothing (

Y. Chen & Zhang, 2023). In this state, the individual seems to be indifferent to the outside world and does not respond to any stimuli. This attitude of “inaction”, “no effort”, is the sociological derivation of the word “lying flat” (

Ou, 2023). Many scholars have discussed the characteristics of “lying flat” and agreed that individuals truly “lying flat” showed the following characteristics: no goals, no effort, and no action (

Y. Chen & Cao, 2021;

C. Deng, 2022;

Hu & Wang, 2023;

Lin & Gao, 2021;

Ling & Wang, 2023;

C. Ma & Wang, 2022;

Qin & Dai, 2022;

Wei & Wang, 2023). From a cultural perspective, the emergence of the “lying flat” phenomenon in China reflects a tension between traditional Confucian values—emphasizing diligence, perseverance, and societal contribution—and the modern pressures of hyper-competition, economic uncertainty, and social stratification (

Confucius, 2014). As a localized response to these evolving dynamics, “lying flat” may represent not just a psychological reaction, but a cultural adaptation to increasingly perceived futility in achieving success through conventional effort. While “lying flat” has gained particular visibility in China, similar sentiments are observable globally. For instance, in Western societies, movements like “quiet quitting” or the rise of NEETs (Not in Employment, Education, or Training) reflect young people’s disillusionment with traditional success narratives in the context of unstable job markets and escalating social pressures (

Eurofound, 2012). Comparing “lying flat” with global phenomena can provide a broader framework for understanding youth disengagement in different socio-economic systems.

Life satisfaction refers to a cognitive evaluation of one’s life as a whole (

Diener et al., 2009;

Pavot & Diener, 2008). It involves an individual’s judgment or assessment of the overall quality of their life based on their own criteria (

Diener et al., 2009;

Pavot & Diener, 2008). This evaluation often takes into account various domains of life such as work, income, relationships, and health, and reflects a person’s contentment with their life circumstances (

Diener et al., 2009;

Pavot & Diener, 2008). “Lying flat” is an alternative lifestyle chosen by some young people who are dissatisfied with the status quo of life, so can “lying flat” improve an individual’s life satisfaction? Some young people claimed in online forums that “lying flat” was a way of life independently chosen by individuals in the face of pressure, reflecting the subjectivity of human beings, and that “lying flat” can alleviate pressure and anxiety and make individuals happier, with higher levels of life satisfaction (

Cao, 2020;

Feng, 2021;

Luo, 2021;

Z. Ma, 2021;

Sun et al., 2021;

X. Wang, 2018,

2021,

2022;

Yang, 2021). In this sense, “lying flat” might represent a rational and adaptive response to social conditions perceived as unjust or excessively demanding. When structural barriers hinder upward mobility, “lying flat” may serve as a form of psychological self-preservation, minimizing stress and protecting mental health in the short term, which may temporarily increase an individual’s life satisfaction. However, most theorists argue that truly “lying flat” (i.e., giving up the pursuit of goals, making no effort, and taking no action) may cause an individual to lose their enthusiasm and motivation for life, and it will affect the individual’s personal growth and career development, which will in turn decrease their life satisfaction (

Y. Chen & Zhang, 2023;

Q. Liu, 2023;

Song & Qin, 2023;

J. Wang, 2021;

Xiang, 2021). The relation between “lying flat” and life satisfaction is controversial, but no empirical studies have explored it yet. The purpose of our study is to combine cross-sectional and longitudinal studies to examine the relationship between the two.

Although no studies have yet explored the relation of “lying flat” and life satisfaction, some theories can give us some insights. Self-Determination Theory posits that individuals are motivated to pursue activities that satisfy three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness (

Chirkov et al., 2003;

Deci & Ryan, 2000,

2008;

Deci et al., 2001;

Ryan & Deci, 2000). When individuals engage in hard work and when they feel competent in their abilities to accomplish tasks, they are more likely to experience a sense of fulfillment and satisfaction, contributing to overall life satisfaction (

Diener et al., 2003;

Ferreira et al., 2020;

T. Liu et al., 2019;

Morales-García et al., 2024;

Žnidaršič & Marič, 2021). And individuals engaging in “lying flat” do not work hard or do not make an effect, making it difficult to gain a sense of competence, which is not conducive to life satisfaction. Goal-Setting Theory posits that setting specific, challenging goals leads to increase motivation and performance (

Locke & Latham, 2006;

Tubbs, 1986). When individuals set ambitious goals and work diligently toward achieving them, they experience a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction upon goal attainment, which contributes to overall life satisfaction (

Schunk, 1990;

Sheldon & Elliot, 1999;

W. Wang et al., 2017). And individuals engaging in “lying flat” do not have clear goals and are not willing to work hard, which makes it difficult to gain a sense of accomplishment and is not conducive to increasing life satisfaction. Positive Psychology emphasizes the importance of cultivating strengths, virtues, and positive experiences to enhance well-being and life satisfaction (

Fredrickson, 2001;

M. Seligman et al., 2005). From this perspective, working hard can be viewed as a means of self-improvement, personal growth, and leading to greater overall life satisfaction. And individuals who engage in “lying flat” do not have clear achievement goals, do not work hard, and do not make progress, thus losing opportunities for self-improvement and personal growth, which is not conducive to increasing life satisfaction (

Ryff, 1989;

Sheldon & Houser-Marko, 2001;

Waterman, 1993;

Weigold et al., 2020). Therefore, the above theories give us new insights, indicating that the higher the degree of “lying flat”, the worse the life satisfaction.

Additionally, previous studies have confirmed that life satisfaction was influenced by factors such as income, achievement goals, work engagement, and work hours (

Ding et al., 2021;

Ferreira et al., 2020;

FitzRoy & Nolan, 2022;

Hsu et al., 2019;

T. Liu et al., 2019;

Morales-García et al., 2024;

Shao, 2022;

Sheldon & Elliot, 1999;

W. Wang et al., 2017;

Žnidaršič & Marič, 2021). Income that can meet basic needs (such as food, shelter, and healthcare) was found to be positively correlated with life satisfaction (

Ding et al., 2021;

FitzRoy & Nolan, 2022). Progress toward meaningful goals that can boost individuals’ sense of competence was also demonstrated to be associated with greater levels of life satisfaction (

Sheldon & Elliot, 1999;

W. Wang et al., 2017). A positive association between work engagement and life satisfaction was also found (

Ferreira et al., 2020;

T. Liu et al., 2019;

Morales-García et al., 2024;

Žnidaršič & Marič, 2021). That is, when individuals are fully engaged in their work, experiencing a sense of purpose, involvement, and enthusiasm, it often spills over into other areas of their life, contributing to higher levels of overall life satisfaction (

Ferreira et al., 2020;

T. Liu et al., 2019;

Morales-García et al., 2024;

Žnidaršič & Marič, 2021). Research suggested that too much free time reduced life satisfaction, and there was an optimal number of working hours conducive to life satisfaction (

Hsu et al., 2019;

Shao, 2022). Individuals who engage in “lying flat” (have no goals, do not work hard, and do not make progress), will have a lower income, which cannot meet basic needs; at the same time, it is difficult to experience a sense of purpose, sense of competence, and sense of fulfillment, and this makes individuals prone to falling into ruminative thinking, all of which will lead to a decline in life satisfaction (

Deci & Ryan, 2000;

FitzRoy & Nolan, 2022;

Huppert & So, 2013;

Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008;

Ryff, 1989;

Sheldon & Niemiec, 2006). Therefore, it is reasonable to put forward the following hypothesis: the higher the degree of “lying flat”, the worse the life satisfaction.

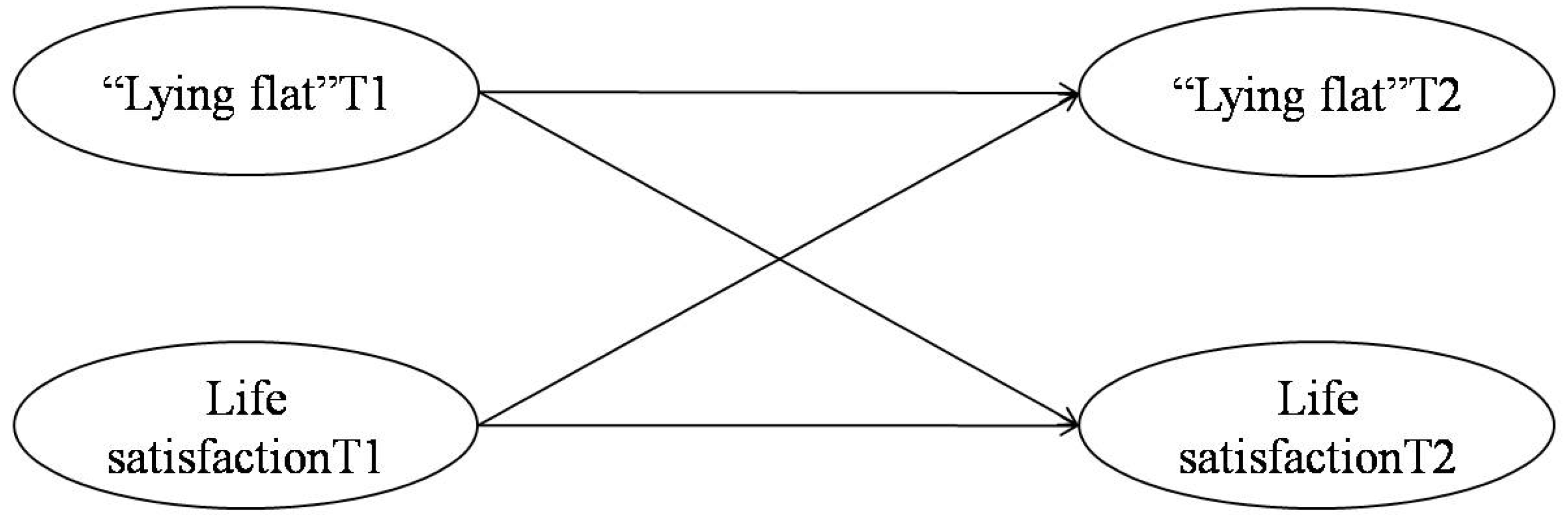

In this study, we sought to explore the relation between “lying flat” and life satisfaction. We combined a cross-sectional (Study 1) and longitudinal study (Study 2) to explore the relation of “lying flat” and life satisfaction. We proposed that “lying flat” would be negatively associated with life satisfaction and that there would be temporal directionality, meaning that “lying flat” would negatively predict life satisfaction over time. Each study (Study 1 and Study 2) utilized independent samples.

4. Discussion

In this study, we revealed the relation of “lying flat” and life satisfaction for the first time. The cross-sectional study found that there was a significant negative correlation between the degree of “lying flat” and life satisfaction, and the longitudinal study found that “lying flat” negatively predicted life satisfaction one month later; i.e., there was a temporal directionality between the two.

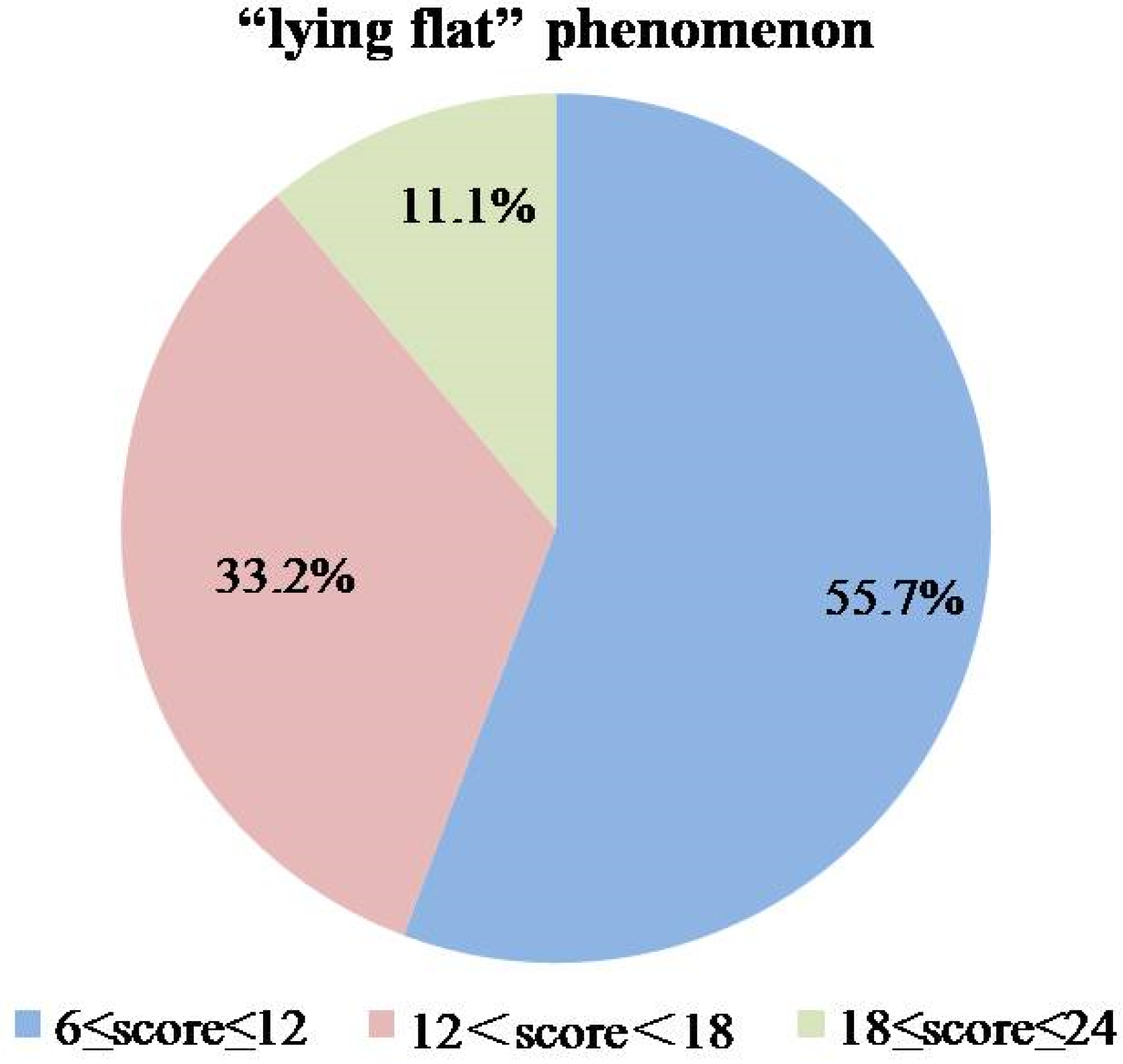

Our study found that 11.1% of young participants were more likely to engage in “lying flat”, and, based on OECD statistics for 2024, the proportion of “NEET” youth in most OECD member countries was above 10% (

OECD, 2024), which indicates that the number of young people who are “lying flat” is not small around the world. Furthermore, the implications of “lying flat” should also be understood within broader socio-cultural frameworks. In Chinese society, deeply rooted in Confucianism, values such as industriousness, perseverance, and the pursuit of upward mobility have long been emphasized (

Confucius, 2014). However, with the rise of hyper-competition, economic inequality, and limited social mobility, young individuals increasingly perceive traditional ideals as unattainable. Consequently, “lying flat” may function as a means of symbolic resistance to entrenched social expectations.

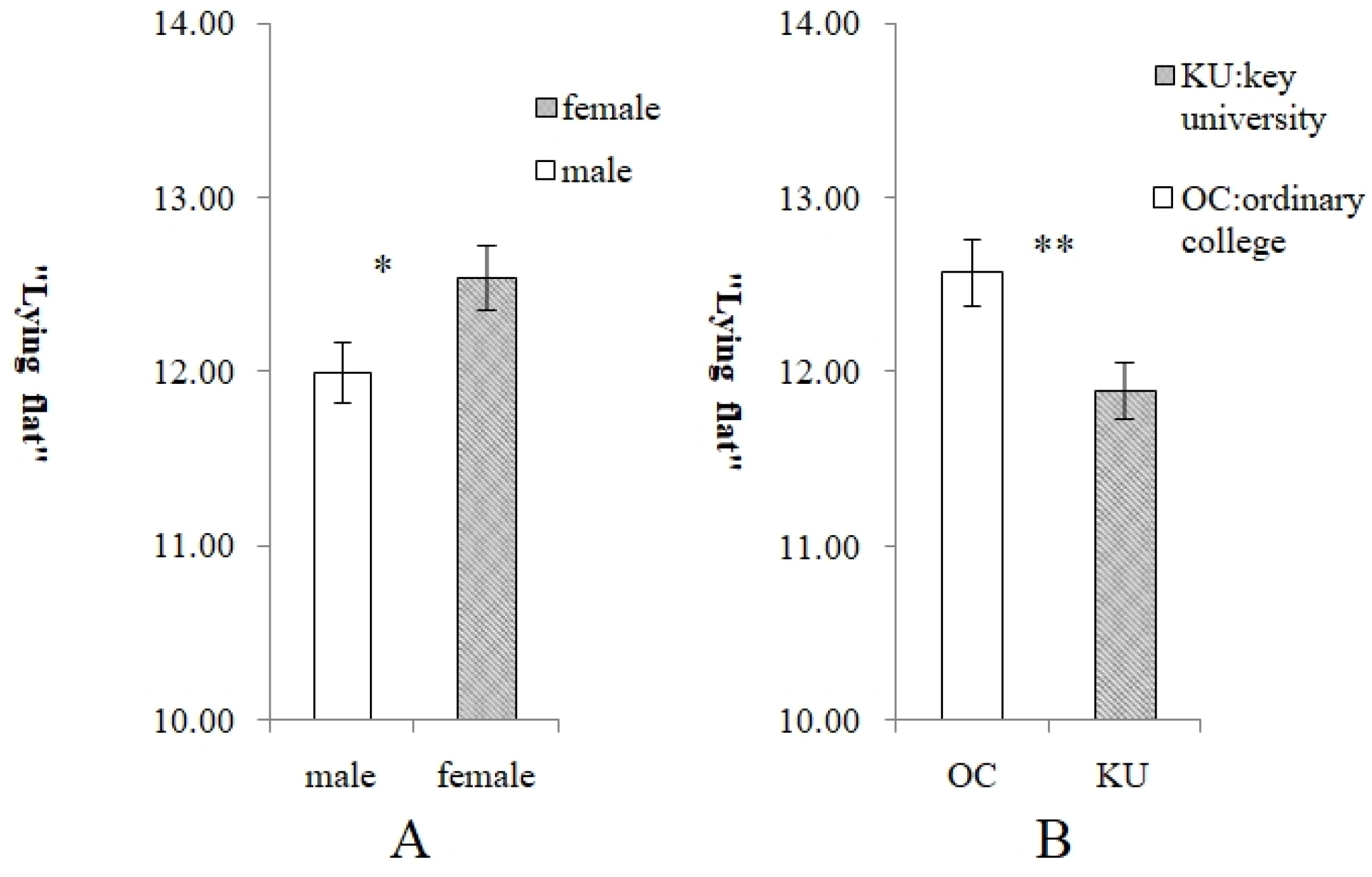

Our study also found that the degree of “lying flat” was significantly higher in the youth from the ordinary college than from the key university. In China, individuals who were admitted to the key university needed to perform better academically, so they needed to expend more effort and had more resilience in the face of difficulties, compared with those who were admitted to the ordinary college. Therefore, in the face of the ever-involving social environment, the youth from the key university were less likely to choose to engage in “lying flat” than those from the ordinary college.

Our study also found that the degree of “lying flat” of the female participants was significantly higher than that of the male participants. While this may be partly rooted in traditional gender socialization, in which men are expected to be ambitious and resilient, and women are encouraged to be cautious and risk-averse (

Ebrey, 1993;

Huang, 1990;

Johnson, 1983;

Mann, 1997;

Dai, 2010), it is also important to consider the evolving and often conflicting expectations placed on modern women. In contemporary Chinese society, women are increasingly expected to excel academically and professionally while also fulfilling traditional family roles. This dual burden may lead to heightened stress, fatigue, and ultimately disengagement. Structural barriers such as gender discrimination in the workplace, wage inequality, and pressures related to marriage and childbearing further undermine women’s perceived control over their life trajectories and future outcomes. As a result, some women may adopt “lying flat” as a form of psychological self-protection or coping in response to the limited and conflicting options available to them.

More importantly, we found temporal directionality between “lying flat” and life satisfaction; that is, “lying flat” significantly negatively predicted life satisfaction. Individuals engaging in more “lying flat” behaviors (giving up pursuing their goals, not working hard, and not making progress) may have difficulty not only in obtaining opportunities for high pay but also in obtaining opportunities for personal growth and realizing achievement goals, all of which have a negative impact on life satisfaction (

Deci & Ryan, 2000;

FitzRoy & Nolan, 2022;

Ryff, 1989;

Sheldon & Houser-Marko, 2001;

Waterman, 1993;

Weigold et al., 2020). On the other hand, this may also be related to the fact that all the participants in this study were Chinese, and that in Chinese culture, it has always been emphasized that “Heaven rewards the hard-working” and that happiness is achieved through struggle (

Confucius, 2014), with those who do not work hard and do not make progress behaving contrarily to the traditional culture, making it difficult to gain social acceptance, which is not conducive to increasing life satisfaction. This study was the first to use empirical research to prove that the higher the degree of “lying flat”, the lower the life satisfaction. It extends the existing literature on the determinants of subjective well-being by highlighting the negative consequences of avoidance-oriented motivational patterns—an area often underexplored in contrast to the emphasis on positive psychological resources such as autonomy, purpose, and engagement.

It is important to note that although our findings demonstrate a significant negative relationship between “lying flat” and life satisfaction, this association may not be entirely attributable to the behavioral stance itself. Some participants may adopt “lying flat” not as a free choice but in response to perceived structural constraints—such as limited opportunities or excessively high societal expectations—which in turn may reduce both motivation and life satisfaction. This psychological process aligns more closely with the notion of “learned helplessness”, in which individuals feel incapable of effecting change in their environment and thus respond with withdrawal and resignation (

M. E. P. Seligman, 1975). In this sense, “lying flat” may reflect broader issues of systemic pressure and psychological strain rather than a simple motivational deficit. Future research should explore the underlying motivations for “lying flat” and distinguish between active “lying flat” and passive “lying flat”, potentially through experimental manipulations or structural equation modeling to account for such confounding factors.

4.1. Implications

This study was the first to use empirical research to find the temporal directionality between “lying flat” and life satisfaction; that is, “lying flat” significantly negatively predicted life satisfaction. This deepens our theoretical understanding of “lying flat” as a psychological coping strategy. Rather than mere behavioral withdrawal, “lying flat” may serve as a temporary relief mechanism in the face of overwhelming pressure yet may come at the cost of long-term psychological functioning. This insight contributes to ongoing discussions about adaptive versus maladaptive disengagement.

In addition to its theoretical contributions, this study also offers valuable practical implications. In educational settings, understanding the psychological roots of the “lying flat” attitude could help develop programs that promote intrinsic motivation, goal clarity, and resilience among students. Schools and universities might consider creating more autonomy-supportive environments and fostering a sense of purpose beyond conventional academic achievement. In workplace contexts, organizations could address early-career disengagement by designing jobs that offer meaningful tasks, flexible goal-setting, and opportunities for personal development. Emphasizing employee well-being and psychological needs might prevent youth burnout and turnover. At the policy level, these results call for reflection on systemic sources of youth dissatisfaction—such as housing unaffordability, hyper-competition, and job insecurity. Public initiatives that alleviate structural pressures and provide pathways for self-realization may help reduce the appeal of “lying flat” as a coping mechanism.

4.2. Limitations

This study also has some limitations. First, the exclusive use of a Chinese university student sample limits the generalizability of the findings. These participants were at a particular developmental stage and were exposed to specific societal pressures—such as academic competition, employment uncertainty, and shifting identity expectations—which might have intensified the observed association between “lying flat” and life satisfaction. Future research should examine more diverse samples across different age groups, educational backgrounds, occupational settings, and cultural contexts to assess the robustness and universality of the findings.

Second, the operationalization of the “lying flat” construct in this study was relatively narrow, focusing primarily on motivational withdrawal and behavioral disengagement. This may have caused more nuanced or contextually adaptive forms of “lying flat” to be overlooked. For example, some individuals may adopt “lying flat” as a reflective or strategic coping mechanism in response to overwhelming societal demands. Such forms of disengagement may not be inherently maladaptive. Future work should develop more refined and context-sensitive measurement tools that can differentiate between various types and functions of “lying flat”.

Third, although we conceptualize “lying flat” as a novel sociocultural construct, it may have a conceptual overlap with existing psychological constructs such as amotivation, learned helplessness, or apathy. These constructs similarly capture motivational collapse or disengagement from goals and expectations. Future research should consider comparing and integrating these frameworks to clarify whether “lying flat” represents a culturally specific manifestation of these phenomena or constitutes an independent motivational stance.

Finally, the longitudinal design in Study 2 involved only a one-month interval. While this design allowed for the identification of temporal directionality, longer follow-up periods are needed to evaluate the stability and long-term implications of the observed effects.