Written Exposure Therapy for PTSD Integrated with Cognitive Behavioral Coping Skills for Cannabis Use Disorder After Recent Sexual Assault: A Case Series

Abstract

1. Introduction

Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measures

2.1.1. PTSD

2.1.2. Substance Use

2.2. Integrated Intervention

3. Results

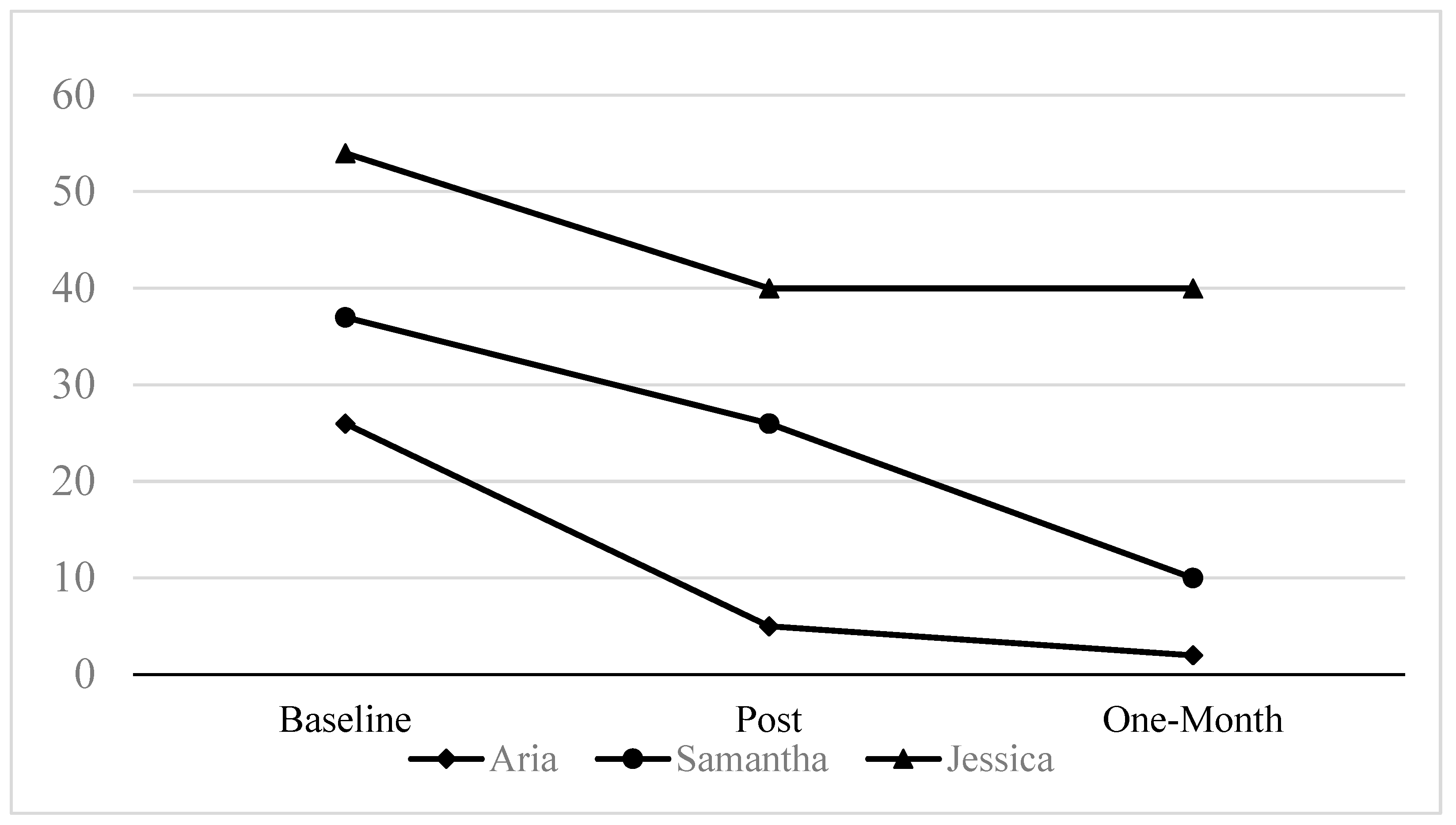

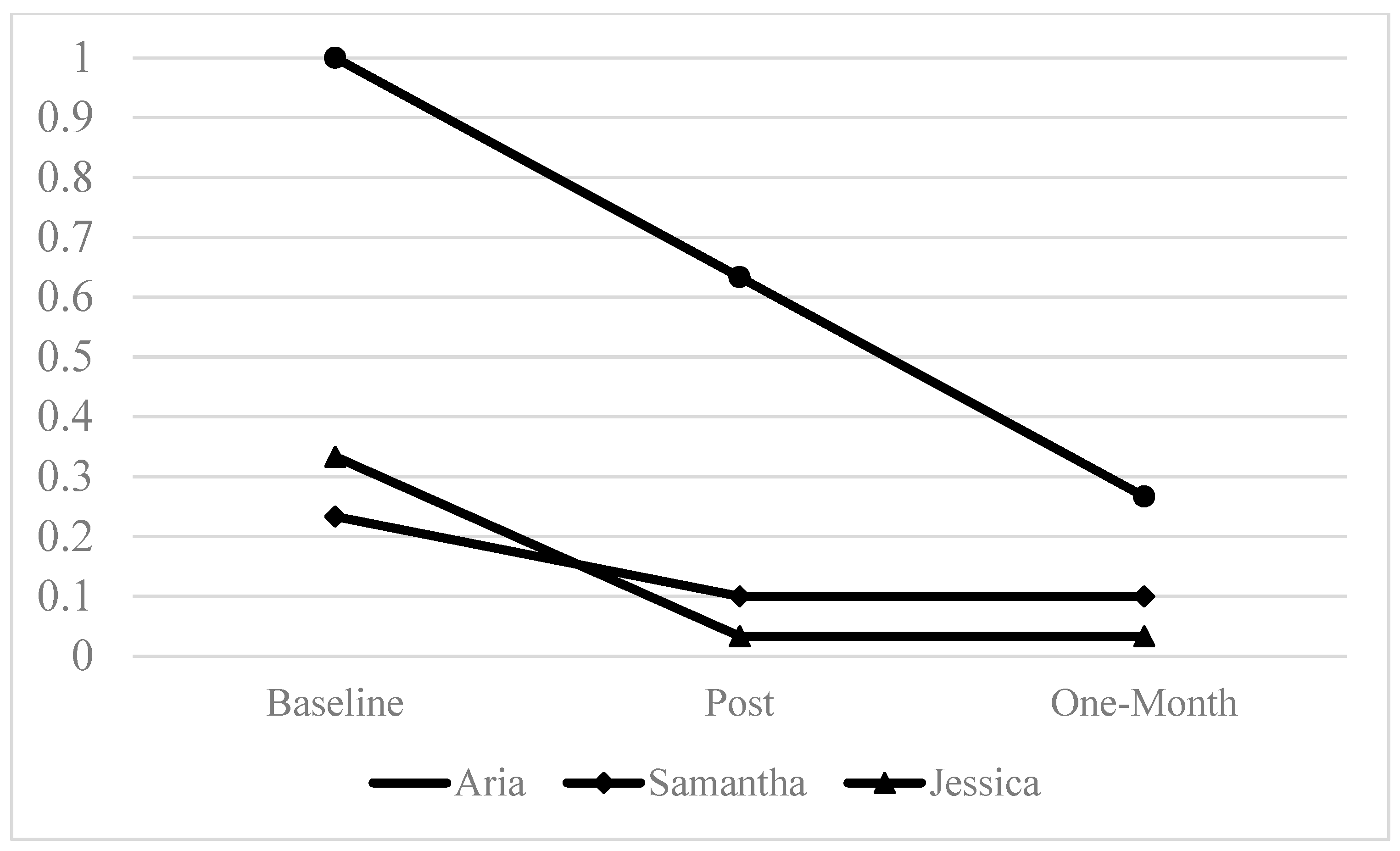

3.1. Cannabis Outcomes

3.2. PTSD Symptom Outcomes

3.3. Case Series

3.3.1. Case 1: Aria

3.3.2. Case 2: Samantha

3.3.3. Case 3: Jessica

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| CUD | Cannabis Use Disorder |

| PTSD | Posttraumatic Stress Disorder |

| SA | Sexual Assault |

| WET | Written Exposure Therapy |

References

- Back, S. E., Jarnecke, A. M., Norman, S. B., Zaur, A. J., & Hien, D. A. (2024). State of the science: Treatment of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorders. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 37(6), 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, S. E., Killeen, T. K., Mills, K. L., & Cotton, B. D. (2014b). Concurrent treatment of PTSD and substance use disorders using prolonged exposure (COPE): Therapist guide. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Back, S. E., Killeen, T. K., Teer, A. P., Hartwell, E. E., Federline, A., Beylotte, F., & Cox, E. (2014a). Substance use disorders and PTSD: An exploratory study of treatment preferences among military veterans. Addictive Behaviors, 39(2), 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basile, K. C., Smith, S. G., Kresnow, M. J., Khatiwada, S., & Leemis, R. W. (2022). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey: 2016/2017 report on sexual violence. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/124625/cdc_124625_DS1.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Becker, M. P., Collins, P. F., Schultz, A., Urošević, S., Schmaling, B., & Luciana, M. (2018). Longitudinal changes in cognition in young adult cannabis users. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 40(6), 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedard-Gilligan, M., Lehinger, E., Cornell-Maier, S., Holloway, A., & Zoellner, L. (2022). Effects of cannabis on PTSD recovery: Review of the literature and clinical insights. Current Addiction Reports, 9(3), 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blevins, C. E., Banes, K. E., Stephens, R. S., Walker, D. D., & Roffman, R. A. (2016). Change in motives among frequent cannabis-using adolescents: Predicting treatment outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 167, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, D. K. (2003). Lifetime physical and sexual abuse, substance abuse, depression, and suicide attempts among native american women. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 24(3), 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordieri, M. J., Tull, M. T., McDermott, M. J., & Gratz, K. L. (2014). The moderating role of experiential avoidance in the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity and cannabis dependence. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 3(4), 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, G., Bagge, C. L., & Orozco, R. (2016). A literature review and meta-analyses of cannabis use and suicidality. Journal of Affective Disorders, 195, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovin, M. J., & Marx, B. P. (2023). The problem with overreliance on the PCL–5 as a measure of PTSD diagnostic status. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 30(1), 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujarski, S. J., Galang, J. N., Short, N. A., Trafton, J. A., Gifford, E. V., Kimerling, R., Vujanovic, A. A., McKee, L. G., & Bonn-Miller, M. O. (2016). Cannabis use disorder treatment barriers and facilitators among veterans with PTSD. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(1), 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, K. B. (1997). Reliability and validity of the time-line follow-back interview among psychiatric outpatients: A preliminary report. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 11(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauchard, E., Levin, K. H., Copersino, M. L., Heishman, S. J., & Gorelick, D. A. (2013). Motivations to quit cannabis use in an adult non-treatment sample: Are they related to relapse? Addictive Behaviors, 38(9), 2422–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, K., & Weinstein, A. (2018). The effects of cannabinoids on executive functions: Evidence from cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids—A systematic review. Brain Sciences, 8(3), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crean, R. D., Crane, N. A., & Mason, B. J. (2011). An evidence-based review of acute and long-term effects of cannabis use on executive cognitive functions. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 5(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalgleish, T., Black, M., Johnston, D., & Bevan, A. (2020). Transdiagnostic approaches to mental health problems: Current status and future directions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(3), 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJesus, C. R., Trendel, S. L., & Sloan, D. M. (2024). A systematic review of written exposure therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 16(Suppl. 3), S620–S626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep, C., Bhat, V., Wijeysundera, D. N., Clarke, H. A., & Ladha, K. S. (2022). The association between recent cannabis use and suicidal ideation in adults: A population-based analysis of the NHANES from 2005 to 2018. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 67(4), 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, E. R. (2020). Risk for mental disorders associated with sexual assault: A meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(5), 1011–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, E. R., Brill, C. D., & Ullman, S. E. (2019). Social reactions to disclosure of interpersonal violence and psychopathology: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 72, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, E. R., DeCou, C. R., & Fitzpatrick, S. (2022a). Associations between sexual assault and suicidal thoughts and behavior: A meta-analysis. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 14(7), 1208–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, E. R., Jaffe, A. E., Bedard-Gilligan, M., & Fitzpatrick, S. (2023). PTSD in the year following sexual assault: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(2), 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, E. R., Krahé, B., & Zinzow, H. (2021). The global prevalence of sexual assault: A systematic review of international research since 2010. Psychology of Violence, 11(5), 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, E. R., Ruzek, J. I., Cordova, M. J., Fitzpatrick, S., Merchant, L., Stewart, T., Santos, J. P., Mohr, J., & Bedard-Gilligan, M. (2022b). Supporter-focused early intervention for recent sexual assault survivors: Study protocol for a pilot randomized clinical trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 119, 106848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escoffery, C., Lebow-Skelley, E., Udelson, H., Böing, E. A., Wood, R., Fernandez, M. E., & Mullen, P. D. (2019). A scoping study of frameworks for adapting public health evidence-based interventions. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 9(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrelly, K. N., Keough, M. T., & Wardell, J. D. (2024). Indirect associations between ptsd symptoms and cannabis problems in young adults: The unique roles of cannabis coping motives and medicinal use orientation. Substance Use & Misuse, 59(9), 1431–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Artamendi, S., Fernández-Hermida, J. R., García-Fernández, G., Secades-Villa, R., & García-Rodríguez, O. (2012). Motivation for change and barriers to treatment among young cannabis users. European Addiction Research, 19(1), 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkus, S. R., Raudales, A. M., Rafiuddin, H. S., Weiss, N. H., Messman, B. A., & Contractor, A. A. (2023). The posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) checklist for DSM–5: A systematic review of existing psychometric evidence. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 30(1), 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, N., Krumeich, A., Havermans, R. C., Smeets, F., & Jansen, A. (2014). Why clinicians do not implement integrated treatment for comorbid substance use disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: A qualitative study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 22821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutkind, S., Fink, D. S., Shmulewitz, D., Stohl, M., & Hasin, D. (2021). Psychosocial and health problems associated with alcohol use disorder and cannabis use disorder in U.S. adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 229, 109137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutkind, S., Shmulewitz, D., & Hasin, D. (2023). Sex differences in cannabis use disorder and associated psychosocial problems among US adults, 2012–2013. Preventive Medicine, 168, 107422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, C. K., Shapiro, M., Rheingold, A. A., Gilmore, A. K., Barber, S., Greenway, E., & Moreland, A. (2023). Perceived barriers and facilitators to treatment for alcohol misuse among survivors and victim service professionals following sexual assault and intimate partner violence. Violence and Victims, 38(5), 645–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, C. K., Tilstra-Ferrell, E. L., Salim, S. R., Marx, B. P., Ennis, N., Brady, K. T., Rothbaum, B. O., Saladin, M. E., Gilmore, A. K., Moreland, A. D., & Back, S. E. (2025). Written exposure therapy integrated with cognitive behavioral skills for alcohol misuse: A proof-of-concept study with recent sexual assault survivors. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. In Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, A. H., Lee, C. S., Abbas, B. T., Bo, A., Morgan, H., & Delva, J. (2021). Culturally adapted evidence-based treatments for adults with substance use problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 226, 108856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, W., Leung, J., & Lynskey, M. (2020). The effects of cannabis use on the development of adolescents and young adults. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 2(2020), 461–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, M., & Chassin, L. (2014). Risk pathways among traumatic stress, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and alcohol and drug problems: A test of four hypotheses. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28(3), 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harned, M. S., Schmidt, S. C., Korslund, K. E., & Gallop, R. J. (2021). Does Adding the Dialectical Behavior Therapy Prolonged Exposure (DBT PE) Protocol for PTSD to DBT Improve Outcomes in Public Mental Health Settings? A Pilot Nonrandomized Effectiveness Trial with Benchmarking. Behavior Therapy, 52(3), 639–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, D., Kerridge, B. T., Saha, T. D., Huang, B., Pickering, R., Smith, S. M., Jung, J., Zhang, H., & Grant, B. F. (2016). Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder, 2012–2013: Findings from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions–III. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(6), 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, D., & Walsh, C. (2021). Cannabis use, cannabis use disorder, and comorbid psychiatric illness: A narrative review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, T. A., Bountress, K. E., Adkins, A. E., Svikis, D. S., Gillespie, N. A., Dick, D. M., Amstadter, A. B., & Spit for Science Working Group. (2023). A longitudinal mediational investigation of risk pathways among cannabis use, interpersonal trauma exposure, and trauma-related distress. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 15(6), 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, D. A., Morgan-López, A. A., Saavedra, L. M., Ruglass, L. M., Ye, A., López-Castro, T., Fitzpatrick, S., Killeen, T. K., Norman, S. B., Ebrahimi, C. T., & Back, S. E. (2023). Project harmony: A meta-analysis with individual patient data on behavioral and pharmacologic trials for comorbid posttraumatic stress and alcohol or other drug use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 180(2), 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M. L., Kline, A. C., Saraiya, T. C., Gette, J., Ruglass, L. M., Norman, S. B., Back, S. E., Saavedra, L. M., Hien, D. A., & Morgan-López, A. A. (2024). Cannabis use and trauma-focused treatment for co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis of individual patient data. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 102, 102827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojosa, C. A., Liew, A., An, X., Stevens, J. S., Basu, A., Van Rooij, S. J., House, S. L., Beaudoin, F. L., Zeng, D., Neylan, T. C., Clifford, G. D., Jovanovic, T., Linnstaedt, S. D., Germine, L. T., Rauch, S. L., Haran, J. P., Storrow, A. B., Lewandowski, C., Hendry, P. L., … Fani, N. (2024). Associations of alcohol and cannabis use with change in posttraumatic stress disorder and depression symptoms over time in recently trauma-exposed individuals. Psychological Medicine, 54(2), 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S. C., Zare, M., Haeny, A. M., & Williams, M. T. (2024). Racial stress, racial trauma, and evidence-based strategies for coping and empowerment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 20, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffers, A. M., Glantz, S., Byers, A., & Keyhani, S. (2021). Sociodemographic characteristics associated with and prevalence and frequency of cannabis use among adults in the US. JAMA Network Open, 4(11), e2136571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, A., Quainoo, S., Nich, C., Babuscio, T. A., Funaro, M. C., & Carroll, K. M. (2022). Racial and ethnic differences in alcohol, cannabis, and illicit substance use treatment: A systematic review and narrative synthesis of studies done in the USA. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(8), 660–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karila, L., Roux, P., Rolland, B., Benyamina, A., Reynaud, M., Aubin, H.-J., & Lancon, C. (2014). Acute and long-term effects of cannabis use: A review. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 20(25), 4112–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevorkian, S., Bonn-Miller, M. O., Belendiuk, K., Carney, D. M., Roberson-Nay, R., & Berenz, E. C. (2015). Associations among trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, cannabis use, and cannabis use disorder in a nationally representative epidemiologic sample. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(3), 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, A. C., Panza, K. E., Lyons, R., Kehle-Forbes, S. M., Hien, D. A., & Norman, S. B. (2023). Trauma-focused treatment for comorbid post-traumatic stress and substance use disorder. Nature Reviews Psychology, 2(1), 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, L. B., Whiteman, S. E., Petri, J. M., Spitzer, E. G., & Weathers, F. W. (2022). Self-rated versus clinician-rated assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder: An evaluation of discrepancies between the PTSD checklist for DSM-5 and the clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM-5. Assessment, 30(5), 1590–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, E., Kuhns, L., & Cousijn, J. (2021). The short-term and long-term effects of cannabis on cognition: Recent advances in the field. Current Opinion in Psychology, 38, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, D. V., Weiller, E., Amorim, P., Bonora, I., Sheehan, K. H., Janavs, J., & Dunbar, G. C. (1997). The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: Reliability and validity according to the CIDI. European Psychiatry, 12(5), 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Y., Brook, J. S., Finch, S. J., & Brook, D. W. (2018). Trajectories of cannabis use beginning in adolescence associated with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in the mid-thirties. Substance Abuse, 39(1), 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, R. F., Hefner, K., Frohe, T., Murray, A., Rosenheck, R. A., Watts, B. V., & Sofuoglu, M. (2017). Exclusion of participants based on substance use status: Findings from randomized controlled trials of treatments for PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 89, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, J., Chan, G. C. K., Hides, L., & Hall, W. D. (2020). What is the prevalence and risk of cannabis use disorders among people who use cannabis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 109, 106479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maples-Keller, J. L., Watkins, L., Hellman, N., Phillips, N. L., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2024). Treatment approaches for posttraumatic stress disorder derived from basic research on fear extinction. Biological Psychiatry, 97, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P., Murray, L. K., Darnell, D., & Dorsey, S. (2018). Transdiagnostic treatment approaches for greater public health impact: Implementing principles of evidence-based mental health interventions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 25(4), 50. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, B. P., Lee, D. J., Norman, S. B., Bovin, M. J., Sloan, D. M., Weathers, F. W., Keane, T. M., & Schnurr, P. P. (2022). Reliable and clinically significant change in the clinician-administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 and PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 among male veterans. Psychological Assessment, 34(2), 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, D. T., Neighbors, H. W., Mezuk, B., Elliott, M. R., & Fleischer, N. L. (2023). Racial/ethnic discrimination and tobacco and cannabis use outcomes among US adults. Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment, 148, 208958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, J. L., Ruggiero, K. J., Resnick, H. S., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2010). Incapacitated, forcible, and drug/alcohol-facilitated rape in relation to binge drinking, marijuana use, and illicit drug use: A national survey. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(1), 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, J., Malecha, A., Gist, J., Watson, K., Batten, E., Hall, I., & Smith, S. (2005). Intimate partner sexual assault against women and associated victim substance use, suicidality, and risk factors for femicide. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 26(9), 953–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlduff, C., Forster, M., Carter, E., Davies, J., Thomas, S., Turner, K. M., Wilson, C. B., & Sanders, M. R. (2020). Model of engaging communities collaboratively: Working towards an integration of implementation science, cultural adaptation and engagement. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 13(1), 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshberg-Cohen, S., Cook, J. M., Bin-Mahfouz, A., & Petrakis, I. L. (2024). Written exposure therapy for veterans with co-occurring substance use disorders and PTSD: Study design of a randomized clinical trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 139, 107475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metrik, J., Stevens, A. K., Gunn, R. L., Borsari, B., & Jackson, K. M. (2020). Cannabis use and posttraumatic stress disorder: Prospective evidence from a longitudinal study of veterans. Psychological Medicine, 52(3), 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, L., Dixon, S., & Mantey, D. S. (2022). Racial and ethnic differences in cannabis use and cannabis use disorder: Implications for researchers. Current Addiction Reports, 9(1), 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mootz, J. J., Fennig, M., & Wainberg, M. L. (2022). Barriers and facilitators of implementing integrated interventions for alcohol misuse and intimate partner violence: A qualitative examination with diverse experts. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 137, 108694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, R. E., & Oudekerk, B. A. (2019). Criminal victimization, 2018 (NCJ 253043). US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for PTSD. (2024). PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Available online: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/ (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2003). Project match monograph series. volume 3. cognitive-behavioral coping skills therapy manual. In A clinical research guide for therapist treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Google Scholar]

- Nillni, Y. I., Baul, T. D., Paul, E., Godfrey, L. B., Sloan, D. M., & Valentine, S. E. (2023). Written exposure therapy for treatment of perinatal PTSD among women with comorbid PTSD and SUD: A pilot study examining feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effectiveness. General Hospital Psychiatry, 83, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papini, S., Ruglass, L. M., Lopez-Castro, T., Powers, M. B., Smits, J. A. J., & Hien, D. A. (2017). Chronic cannabis use is associated with impaired fear extinction in humans. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(1), 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pocuca, N., Chadi, N., Vergunst, F., Parent, S., Côté, S. M., Boivin, M., Tremblay, R. E., Séguin, J. R., & Castellanos-Ryan, N. (2023). Prospective polysubstance use profiles among adolescents with early-onset cannabis use, and their association with cannabis outcomes in emerging adulthood. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 22(4), 2543–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S. M., Sobell, L. C., Sobell, M. B., & Leo, G. I. (2014). Reliability of the timeline followback for cocaine, cannabis, and cigarette use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28(1), 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodas, J. D., George, T. P., & Hassan, A. N. (2024). A systematic review of the clinical effects of cannabis and cannabinoids in posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and symptom clusters. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 85(1), 23r14862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacht, R. L., Wenzel, K. R., Meyer, L. E., Mette, M., Mallik-Kane, K., Rabalais, A., Berg, S. K., & Fishman, M. (2023). A pilot test of Written Exposure Therapy for PTSD in residential substance use treatment. The American Journal on Addictions, 32(5), 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, B. E., Grucza, R. A., & Plunk, A. D. (2021, October). Association of racial disparity of cannabis possession arrests among adults and youths with statewide cannabis decriminalization and legalization. In JAMA Health Forum (Vol. 2, No. 10, p. e213435). American Medical Association. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey, R. C., McNulty, J. K., Moore, T. M., & Stuart, G. L. (2015). Being the victim of violence during a date predicts next-day cannabis use among female college students. Addiction, 111(3), 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan, D. M., & Marx, B. P. (2019). Written exposure therapy for PTSD: A brief treatment approach for mental health professionals. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, D. M., & Marx, B. P. (2021). Written exposure therapy (WET) for PTSD: A brief evidence-based treatment for reduced dropouts and improved outcomes in fewer sessions. PESI. Available online: https://catalog.pesi.com/item/written-exposure-therapy-wet-ptsd-evidencebased-treatment-reduced-dropouts-improved-outcomes-sessions-78942 (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Sloan, D. M., Marx, B. P., Acierno, R., Messina, M., Muzzy, W., Gallagher, M. W., Litwack, S., & Sloan, C. (2023). Written exposure therapy vs. prolonged exposure therapy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 80(11), 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobell, L. C., & Sobell, M. B. (1992). Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods (pp. 41–72). Humana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanidou, T., Hughes, E., Kester, K., Edmondson, A., Majeed-Ariss, R., Smith, C., Ariss, S., Brooker, C., Gilchrist, G., Kendal, S., Lucock, M., Maxted, F., Perot, C., Shallcross, R., Trevillion, K., & Lloyd-Evans, B. (2020). The identification and treatment of mental health and substance misuse problems in sexual assault services: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 15(4), e0231260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinert, C., Hofmann, M., Leichsenring, F., & Kruse, J. (2015). The course of PTSD in naturalistic long-term studies: High variability of outcomes. A systematic review. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 69(7), 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S. H., Khoury, J. M. B., Watt, M. C., Collins, P., DeGrace, S., & Romero-Sanchiz, P. (2024). Effects of sexual assault vs. other traumatic experiences on emotional and cannabis use outcomes in regular cannabis users with trauma histories: Moderation by gender? Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1386264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration. (2020). 2019 NSDUH detailed tables. CBHSQ data. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2019-nsduh-detailed-tables (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Swain, H., Short, N. A., McLean, B. S., Tungate, A. S., Lechner, M., Bell, K., Black, J., Buchanan, J., Reese, R., Reed, G., Liberzon, I., Rauch, S. A. M., Kessler, R., & McLean, S. A. (2020). Increased posttraumatic stress symptoms are associated with increased substance use in sexual assault survivors during the year after sexual assault. Biological Psychiatry, 87(9), S297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilstra-Ferrell, E. L., Salim, S. R., López, C., Foster, A., & Hahn, C. K. (2024). Written exposure therapy and dialectical behavior therapy skills training as a novel integrated intervention for women with co-occurring PTSD and eating disorders: Two case studies. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolin, D., Bowe, W., Davis, E., Hannan, S., Springer, K., Worden, B., & Steinman, S. A. (2016). Diagnostic Interview for anxiety, mood, and OCD and related neuropsychiatric disorders (DIAMOND). The Institute of Living, Hartford Healthcare Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, H., Fina, B. A., Marx, B. P., Young-McCaughan, S., Sloan, D. M., Kaplan, A. M., Green, V. R., Blankenship, A., Bryan, C. J., & Peterson, A. L. (2022). Written exposure therapy for suicide in a psychiatric inpatient unit: A case series. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 29(4), 924–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, S. E., & Najdowski, C. J. (2009). Correlates of serious suicidal ideation and attempts in female adult sexual assault survivors. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 39(1), 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, S. E., Relyea, M., Peter-Hagene, L., & Vasquez, A. L. (2013). Trauma histories, substance use coping, PTSD, and problem substance use among sexual assault victims. Addictive Behaviors, 38(6), 2219–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berk-Clark, C., & Patterson Silver Wolf, D. (2017). Mental health help seeking among traumatized individuals: A systematic review of studies assessing the role of substance use and abuse. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 18(1), 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doren, N., Chang, F. H., Nguyen, A., McKenna, K. R., Satre, D. D., & Wiltsey-Stirman, S. (2025). A pilot study of twice-weekly group-based written exposure therapy for veterans in residential substance use treatment: Effects on PTSD and depressive symptoms. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 20(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K., Resnick, H. S., Danielson, C. K., McCauley, J. L., Saunders, B. E., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2014). Patterns of drug and alcohol use associated with lifetime sexual revictimization and current posttraumatic stress disorder among three national samples of adolescent, college, and household-residing women. Addictive Behaviors, 39(3), 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F. W., Blake, D. D., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., & Keane, T. M. (2013). The life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Instrument Available from the National Center for PTSD. Available online: www.ptsd.va.gov (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Weathers, F. W., Bovin, M. J., Lee, D. J., Sloan, D. M., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Keane, T. M., & Marx, B. P. (2018). The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychological Assessment, 30(3), 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. T., Osman, M., Gran-Ruaz, S., & Lopez, J. (2021). Intersection of racism and PTSD: Assessment and treatment of racial stress and trauma. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 8(4), 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worley, C. B., LoSavio, S. T., Aajmain, S., Rosen, C., Stirman, S. W., & Sloan, D. M. (2020). Training during a pandemic: Successes, challenges, and practical guidance from a virtual facilitated learning collaborative training program for written exposure therapy. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(5), 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabik, N. L., Iadipaolo, A., Peters, C. A., Baglot, S. L., Hill, M. N., & Rabinak, C. A. (2024). Dose-dependent effect of acute THC on extinction memory recall and fear renewal: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Psychopharmacology, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabik, N. L., Rabinak, C. A., Peters, C. A., & Iadipaolo, A. (2023). Cannabinoid modulation of corticolimbic activation during extinction learning and fear renewal in adults with posttraumatic stress disorder. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 201, 107758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Session | CBT Skills Targeting CUD | WET Writing Prompt Targeting PTSD |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Psychoeducation Motivational interviewing Goal setting | Write about details of sexual assault |

| 2 | Coping with urges and cravings to use cannabis | Write about details of sexual assault |

| 3 | Managing thoughts about cannabis use | Write about details of the worst part of sexual assault |

| 4 | Provider and patient select one of the following skills in collaboration based on need and relevance: Assertiveness, cannabis refusal skills, or problem-solving | Write about details of the worst part of sexual assault and the impact |

| 5 | Planning for high-risk situations involving cannabis | Write about the impact of sexual assault on one’s life and future |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hahn, C.K.; Salim, S.R.; Tilstra-Ferrell, E.L.; Brady, K.T.; Marx, B.P.; Rothbaum, B.O.; Saladin, M.E.; Guille, C.; Gilmore, A.K.; Back, S.E. Written Exposure Therapy for PTSD Integrated with Cognitive Behavioral Coping Skills for Cannabis Use Disorder After Recent Sexual Assault: A Case Series. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070877

Hahn CK, Salim SR, Tilstra-Ferrell EL, Brady KT, Marx BP, Rothbaum BO, Saladin ME, Guille C, Gilmore AK, Back SE. Written Exposure Therapy for PTSD Integrated with Cognitive Behavioral Coping Skills for Cannabis Use Disorder After Recent Sexual Assault: A Case Series. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):877. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070877

Chicago/Turabian StyleHahn, Christine K., Selime R. Salim, Emily L. Tilstra-Ferrell, Kathleen T. Brady, Brian P. Marx, Barbara O. Rothbaum, Michael E. Saladin, Constance Guille, Amanda K. Gilmore, and Sudie E. Back. 2025. "Written Exposure Therapy for PTSD Integrated with Cognitive Behavioral Coping Skills for Cannabis Use Disorder After Recent Sexual Assault: A Case Series" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070877

APA StyleHahn, C. K., Salim, S. R., Tilstra-Ferrell, E. L., Brady, K. T., Marx, B. P., Rothbaum, B. O., Saladin, M. E., Guille, C., Gilmore, A. K., & Back, S. E. (2025). Written Exposure Therapy for PTSD Integrated with Cognitive Behavioral Coping Skills for Cannabis Use Disorder After Recent Sexual Assault: A Case Series. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070877