The Impact of Cognitive Reappraisal Intervention on Depressive Tendencies in Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

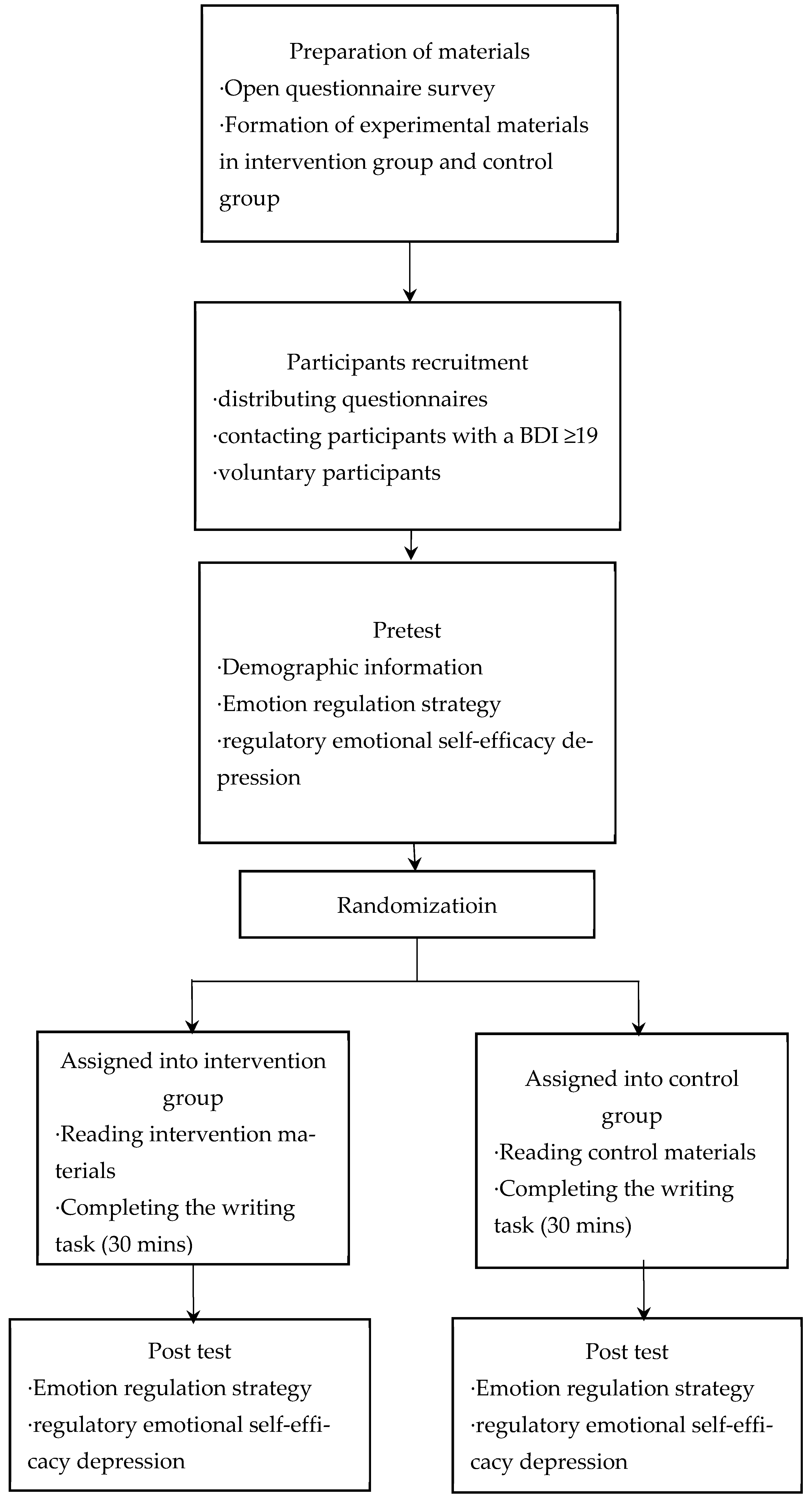

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Emotional Regulation Questionnaire

2.2.2. Emotional Regulation Self-Efficacy Scale

2.2.3. Beck Depression Scale

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Preparation of Experimental Materials

- (1)

- To understand the events and sources that cause college students’ negative emotions, we asked, for example, “Think back over your college life. What were the three things (academic/emotional/interpersonal) that caused you to feel or experience (sadness/pain/depression)? Please be as detailed as possible”.

- (2)

- Some questions asked the participants to write about their experiences and feelings regarding specific events and how they successfully mediated their negative emotions. For example, “When you recall this incident, did you think it was your own problem or the problem of external people or things? Please write down what you were thinking. To make yourself feel better, did you look at the situation from a different angle and convince yourself that it was not as bad as you thought it was? Did you feel better after doing this? Please provide enough details regarding how you convinced yourself or how you changed your mind so that other students can learn from your experience”.

- (3)

- To encourage college students to adopt positive emotional regulation strategies, they were asked to provide advice for themselves. For example, “When something similar happens again, will you just suppress your emotions or try to adjust your emotions? Why? If you were to give advice to a college student going through the same situation, what would you say to that student? Your words may give them ideas to improve their mood and help them overcome difficult situations and negative emotions”.

“After I entered college, I was sad to find that I had drifted apart from my former friends. We went to college in different places, were exposed to different environments and people, and gradually, we went from sharing everything to having nothing to say. At first, I was always sad and depressed, but later I told myself that true friendship does not change because of time or distance, maybe he is just not the right person. Some things cannot be changed; life will not be stagnant because of a person; rather than repressing their own heart, it is better to re-understand, and I am more in tune with friends. Now I have several good buddies, and I’m very thankful for who I was then… I was not consistently immersed in a depressed atmosphere; however, I did actively adjust my emotional state and proactively embraced a new life”.

“The most effective method for avoiding the negative effects of emotional distress is to maintain a healthy lifestyle. There are so many positive moments in your life. Do not dwell too much on the shadows of the past. Try to think about a problem from different angles, and you will be enlightened”.

2.5. Participant Recruitment

2.6. Pretest

2.7. Intervention

2.8. Post-Test

2.9. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. The Homogeneity Analysis of the Variables in the Pretests of the Two Groups

3.2. Analysis of the Intervention Effect

3.3. Test of the Mediating Effect of Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The CR intervention program developed in this study is effective. The intervention method significantly reduces the tendency toward depression among college students.

- (2)

- Regulatory emotional self-efficacy mediates the influence of CR intervention on the levels of depression of college students.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abela, J. R. Z., Brozina, K., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). A test of integration of the activation hypothesis and the diathesis-stress component of the hopelessness theory of depression. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramson, L. Y., Alloy, L. B., Hankin, B. L., Haeffel, G. J., MacCoon, D. G., & Gibb, B. E. (2002). Cognitive vulnerability-stress models of depression in self-regulatory and psychobiological context. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(3), 261–279. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96(2), 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastopoulo, A. D., King, K. A., Besecker, L. H., O’Rourke, S. R., Bray, A. C., & Supple, A. J. (2020). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for college students with ADHD: Temporal stability of improvements in functioning following active treatment. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(6), 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., Ebert, D. D., Green, J. G., Hasking, P., & Murray, E. (2018). WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(7), 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A., Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Gerbino, M., & Pastorelli, C. (2003). Role of affective self-regulatory efficacy in diverse spheres of psychosocial functioning. Child Development, 74(3), 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J. R., & Fergus, T. A. (2020). Emotion regulation self-efficacy mediates the relation between happiness emotion goals and depressive symptoms: A cross-lagged panel design. Emotion, 20(5), 910–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the revised Beck depression inventory. Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Beiter, R., Nash, R., McCrady, M., Rhoades, D., Linscomb, M., Clarahan, M., & Sammut, S. (2015). The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 173(15), 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosan, L., Hoppitt, L., Shelfer, L., Sillence, A., & Mackintosh, B. (2011). Cognitive bias modification for attention and interpretation reduces trait and state anxiety in anxious patients referred to an out-patient service: Results from a pilot study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 42(3), 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G. V., Di Giunta, L., Eisenberg, N., Gerbino, M., Pastorelli, C., & Tramontano, C. (2008). Assessing regulatory emotional self-efficacy in three countries. Psychological Assessment, 20(3), 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, C. S., Hentges, F., Parkinson, M. B., Sheffield, P., Willetts, L., & Cooper, P. (2010). Feasibility of guided cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) self-help for childhood anxiety disorders in primary care. Mental Health in Family Medicine, 7(1), 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, H. L. (2020). Why are humor styles associated with well-being, and does social competence matter? Examining relations to psychological and physical well-being, reappraisal, and social support. Personality and Individual Differences, 154(2), 109641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W., Chen, S., Chen, Y., He, F., Yang, J., & Yuan, J. (2021). The use and change of emotion regulation strategies: The promoting effect of cognitive flexibility. Chinese Science Bulletin, 66(19), 2405–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladstone, T. R., & Beardslee, W. R. (2009). The prevention of depression in children and adolescents: A review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 54(4), 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotlib, I. H., & Joormann, J. (2010). Cognition and depression: Current status and future directions further. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6(1), 285–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Journal of Educational Measurement, 51(3), 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judah, M. R., Milam, A. L., Hager, N. M., Webb, T. N., Hamrick, H. C., & Meca, A. (2022). Cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression moderate the association between social anxiety and depression. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 44(4), 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J. B., Jacobs, R. H., & Reinecke, M. A. (2007). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent depression: A meta-analytic investigation of changes in effect-size estimates. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(11), 1403–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupfer, D. J., Frank, E., & Phillips, M. L. (2016). Major depressive disorder: New clinical, neurobiological, and treatment perspectives. Focus, 14(2), 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeMoult, J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2019). Depression: A cognitive perspective. Clinical Psychology Review, 6(8), 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Yang, X. G., Zheng, W. Y., & Wang, C. (2019). Emotional regulation goals of young adults with depression inclination: An event-related potential study. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 51(6), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S. Y., Liu, C., Rotaru, K., Li, K., Wei, X., Yuan, S., Yang, Q., Ren, L., & Liu, X. (2022). The relations between emotion regulation, depression and anxiety among medical staff during the late stage of COVID-19 pandemic: A network analysis. Psychiatry Research, 317, 114–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D. C., Bi, J. R., Zhang, X. X., Zhu, F., & Wang, Y. (2022). Successful emotion regulation via cognitive reappraisal in authentic pride: Behavioral and event-related potential evidence. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 16, 983674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Ren, G. Q., & Qu, K. J. (2023). The emotion regulation effect of cognitive reappraisal strategies on college students with depression tendency. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 31(1), 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P., Huang, M. M., He, B. K., Pan, W. H., & Zhao, S. Y. (2021). The influence of undergraduates’ loneliness on depression: Based on latent moderated structural equation. Journal of Psychological Science, 44(5), 1186–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, A. R., Kosonogov, V., & Lyusin, D. (2021). Expressive suppression versus cognitive reappraisal: Effects on self-report and peripheral psychophysiology. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 167(2), 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S. A., Zoellner, L. A., & Mollenholt, N. (2008). Are expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal associated with stress-related symptoms? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(9), 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, T., & Hagen, K. A. (2014). Adolescent mental health: Prevention and intervention. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, E. Q., Wigfield, A., & Hulleman, C. S. (2020). More useful or not so bad? Examining the effects of utility value and cost reduction interventions in college physics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(1), 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B. B., Zhu, Z. P., Jiang, J. L., & Li, C. B. (2017). A review of brief cognitive behavioral therapy in application to depressive disorder. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 31(9), 670–676. [Google Scholar]

- Sirey, J. A., Banerjee, S., Marino, P., Bruce, M. L., Halkett, A., Turnwald, M., Chiang, C., Liles, B., Artis, A., Blow, F., & Kales, H. C. (2017). Adherence to depression treatment in primary care. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(11), 1129–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D. L., Dong, Y., Yu, G. L., & Wen, S. F. (2010). The regulatory emotional self-efficacy: A new research topic. Advances in Psychological Science, 18(4), 598–604. [Google Scholar]

- Visted, E., Vøllestad, J., Nielsen, M. B., & Schanche, E. (2018). Emotion regulation in current and remitted depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 18(9), 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2011). A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science, 331(6023), 1447–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, G. M., & Wilson, T. D. (2018). Wise interventions: Psychological remedies for social and personal problems. Psychological Review, 125(5), 617–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L., Liu, H. C., Li, Z. Q., & Du, W. (2007). Reliability and validity of emotion regulation questionnaire Chinese revised version. China Journal of Health Psychology, 15(6), 503–505. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M. Y., Han, F. F., Liu, J., Huang, K., Peng, H., Huang, M., & Zhao, Z. (2020). A meta-analysis of detection rate of depression symptoms and related factors in college students. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 34(12), 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. X., Jiang, C. G., Li, J., & Feng, Z. Z. (2015). Neural substrates of abnormal positive emotion regulation in depressed patients. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 23(4), 615–620. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. J., Dou, K., & Liu, Y. (2013). Revision of the scale of regulatory emotional self-efficacy. Journal of Guangzhou University, 12(1), 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z., & Du, J. (2021). A mental health informatics study on the mediating effect of the regulatory emotional self-efficacy. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering, 18(3), 2775–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, C. P., Q., D. Q., Wang, Y. F., Wu, M., Gao, T., & Liu, X. (2022). The effect of cognitive reappraisal and expression suppression on sadness and the recognition of sad scenes: An event-related potential study. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 935007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W. H., Wu, D. J., & Peng, F. (2012). Application of Chinese version of beck depression inventory-II to Chinese first-year college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 20(6), 762–764. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, B., Zhao, J., Zou, L., Yang, X., Zhang, X., Wang, W., Zhao, J., & Chen, J. (2018). Depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress symptoms and suicide risk among graduate students: The mediating influence of emotional regulatory self-efficacy. Psychiatry Research, 264(17), 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y., Zheng, P. P., & Qian, H. H. (2023). Research progress on cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in college students. Chinese Journal of School Doctor, 37(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y. L., Wang, G. f., & Hu, X. Y. (2017). Effect of mindfulness cognitive training on stress and negative emotions of nursing students. Journal of Modern Clinical Medicine, 43(5), 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. H., Sang, B., Liu, Y., & Pan, T. T. (2020). Emotion regulation strategies in adolescents with different depressive symptoms. Journal of Psychological Science, 43(6), 1296–1303. [Google Scholar]

| Intervention Group (n = 49) | Control Group (n = 49) | t | p | Effect Size d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | M ± SD | ||||

| CR | 28.94 ± 5.94 | 28.27 ± 6.67 | 0.53 | 0.599 | 0.11 |

| ES | 15.55 ± 5.74 | 15.61 ± 5.93 | −0.05 | 0.959 | 0.01 |

| RESE | 55.04 ± 9.08 | 53.90 ± 8.73 | 0.64 | 0.527 | 0.13 |

| Depression | 24.47 ± 4.34 | 25.96 ± 5.24 | −1.53 | 0.128 | 0.31 |

| Variables | Groups | Pretest (n = 49) M ± SD | Post-Test (n = 49) M ± SD | Time Main Effect | Group Main Effect | Time–Group Interaction Effect | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | η2p | F | η2p | F | η2p | ||||

| CR | Intervention | 28.94 ± 5.94 | 30.92 ± 6.05 | 8.20 ** | 0.08 | 1.42 | 0.02 | 2.73 | 0.03 |

| Control | 28.27 ± 6.67 | 28.80 ± 6.09 | |||||||

| ES | Intervention | 15.55 ± 5.74 | 16.04 ± 5.88 | 1.04 | 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| Control | 15.61 ± 5.93 | 16.02 ± 5.09 | |||||||

| RESE | Intervention | 55.04 ± 9.08 | 58.98 ± 9.73 | 15.06 *** | 0.14 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 3.80 * | 0.04 |

| Control | 53.90 ± 8.73 | 55.20 ± 9.35 | |||||||

| Depression | Intervention | 24.47 ± 4.34 | 18.24 ± 10.61 | 11.22 *** | 0.11 | 11.03 *** | 0.10 | 9.34 ** | 0.09 |

| Control | 25.96 ± 5.24 | 25.67 ± 10.51 | |||||||

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | R2 | SE | B | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Intervention condition | 0.11 | 2.13 | 7.43 | 3.50 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 0.12 | 2.12 | 2.83 | 1.33 | 0.187 | |

| RESE | Intervention condition | 0.14 | 1.93 | −3.78 | −2.06 | 0.042 |

| Gender | 1.83 | −6.18 | −3.37 | 0.124 | ||

| Depression | Intervention condition | 0.27 | 2.00 | 5.68 | 2.84 | 0.006 |

| RESE | 0.11 | −0.46 | −4.22 | <0.001 | ||

| Gender | 2.08 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.988 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, T.; Liu, K.; Feng, X.; Zhang, X.; She, Z. The Impact of Cognitive Reappraisal Intervention on Depressive Tendencies in Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050562

Lu T, Liu K, Feng X, Zhang X, She Z. The Impact of Cognitive Reappraisal Intervention on Depressive Tendencies in Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):562. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050562

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Ting, Kejing Liu, Xiang Feng, Xinyu Zhang, and Zhuang She. 2025. "The Impact of Cognitive Reappraisal Intervention on Depressive Tendencies in Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050562

APA StyleLu, T., Liu, K., Feng, X., Zhang, X., & She, Z. (2025). The Impact of Cognitive Reappraisal Intervention on Depressive Tendencies in Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050562