2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The initial sample was composed of 386 participants in the “Factors associated with the eating behaviors of LGBTQ+ people” project carried out in Italy between June 2024 and April 2025.

Three inclusion criteria were defined:

Identifying as any LGBTQ+ identity regarding sexual orientation or gender identity (e.g., gay, lesbian, bisexual, pansexual, queer, trans/transgender, non-binary, gender non-conforming, genderfluid, etc.);

Being at least 18 years old;

Being able to read, understand, and write in the Italian language.

One exclusion criterion was defined:

2.2. Procedure

The study procedures were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the American Psychological Association and the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Bioethical Committee of the University of Turin on 30 April 2024 with protocol number 0307736. An online survey was developed using the LimeSurvey platform running version 6.3.8+231204. The link to the survey was disseminated through public flyers at relevant places and events (e.g., LGBTQ+-friendly establishments, local Pride events), the researchers’ personal and professional networks, emails, and through collaboration with gyms, public libraries, and LGBTQ+ associations. The study also employed snowball sampling by asking the participants to send the link and/or flyer to other LGBTQ+ people they may know, disseminating the study through word of mouth. Participants were informed of the general topic of the study, along with possible risks and benefits connected to participation, asked to confirm being at least 18 years old, and asked for consent to participation. Participation was voluntary and completely anonymous. No reward or incentive was offered for participation in the study.

Participants were asked to fill out a sociodemographic sheet, in which they were asked which word best described their sexual orientation and gender identity, as well as to confirm whether they were a trans or otherwise gender-diverse person. Participants who reported both a heterosexual and cisgender identity were not allowed to participate in the study.

Participants responded to a battery of questionnaires surveying aspects related to experiences as LGBTQ+ people, body image, and eating behaviors. Whenever possible, validated questionnaires in the Italian language were used. The full questionnaire took participants an average of 30 min to complete.

A number of response quality control measures were employed. Two attention checks were added at random points throughout the survey. Participants who failed one or more attention checks were excluded from the analyses. The participants’ response time was also screened: responses that had significantly quicker response time compared to the mean were checked for response sets and incoherent responses. Participants also developed an anonymous participant code, which was used to screen for duplicate answers. Finally, participants who entered invalid or insufficient information in the “sexual orientation” or “gender identity” (e.g., using the “Other” field to enter an answer that is not relevant to the respective text field) were excluded. After this data quality screening, 376 participants were retained in the current analyses. Notably, the sample mostly comprised individuals with high education and with good socioeconomic status, which should be kept in mind as it may limit generalizability of the findings.

2.3. Measures

Eating Disorder Inventory—3 (EDI-3;

Garner, 2004;

Giannini et al., 2008): Participants responded to 91 items evaluating eating behaviors, attitudes, body image, and other psychological aspects connected to eating disorders. The EDI-3 uses a 5-point Likert scale assessing the participants’ perceived frequency of the relevant items from “never” to “always”. In this study, three subscales were used.

The low self-esteem subscale involves items related to a low evaluation of one’s subjective personal worth (such as «I feel inadequate» or «I feel secure about myself», reverse scored). Higher scores suggest lower self-esteem.

The emotion dysregulation subscale involves items related to one’s ability in recognizing and regulating one’s emotions (such as «Other people would say that I am emotionally unstable» or «I don’t know what’s going on inside me»). Higher scores suggest lower abilities in emotion regulation.

The Eating Disorder Risk Composite (EDRC) scale score is the sum of the scores from three additional subscales from the EDI-3: the Bulimia subscale, which measures behaviors and attitudes related to overeating (such as «I stuff myself with food»); the “Drive for Thinness” subscale, which measures one’s desire to attain a thinner body (such as «I am preoccupied with the desire to be thinner»); the Body Dissatisfaction subscale, which measures one’s current lack of satisfaction with body parts and their body as a whole (such as «I feel satisfied with the shape of my body», reverse scored). This composite scale is conceptualized as a general evaluation of eating disorder risk rather than pointing to a specific eating disorder. Higher total scores suggest higher general eating disorder risk.

Daily Heterosexist Experiences Questionnaire (

Balsam et al., 2013): Participants responded to 38 items related to daily heterosexist experiences relevant to being LGBTQ+ specifically (some scales from the original were omitted). The scale allows participants to report on whether they had a specific experience or not. The scale was scored in the “Distress” mode, as participants reported on their perceived distress level for each experience (depending on the level of distress, ranging from “did not happen/does not apply to me” and “not at all”—both scored 1 point—to “extreme”—5 points). The scale was translated into Italian. For this study, the vicarious trauma subscale was used, which involves participants reporting about witnessing heterosexist experiences happening to other people (such as «Hearing about hate crimes (e.g., vandalism, physical or sexual assault) that happened to LGBT people you don’t know» or «Hearing other people being called names such as “fag” or “dyke”»). Higher scores correspond to more distressful heterosexist experiences related to vicarious trauma.

Personal Feelings Questionnaire—2 (PFQ-2;

Di Sarno et al., 2022;

D. W. Harder et al., 1993): The Italian version of the PFQ-2 was administered. The PFQ-2 has been used with LGBTQ+ people before (

Scheer & Antebi-Gruszka, 2019) and has been found to have good psychometric properties (

D. W. Harder et al., 1993;

D. Harder & Zalma, 1990). The PFQ-2 comprises 22 items measuring a person’s tendency to experience feelings of guilt and shame by asking them to rate how frequently they experience each sensation (e.g., «Feeling humiliated» or «Feeling you deserve criticism for what you did») on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from “Never” to “All the time or almost always”. Raw scores were computed according to instructions for the Shame subscale. Higher scores are representative of more common feelings of shame.

Body Mass Index (BMI): using participants’ self-reported height and weight, their BMI (ratio between one’s mass and squared height) was computed.

2.4. Data Analysis

All data analyses were performed in RStudio using R version 4.5.1 (

R Core Team, 2024). Two-tailed bivariate correlations between the variables were tested using Pearson’s correlation (r), and results were interpreted according to original guidelines. The PROCESS macro version 5.0 for R (

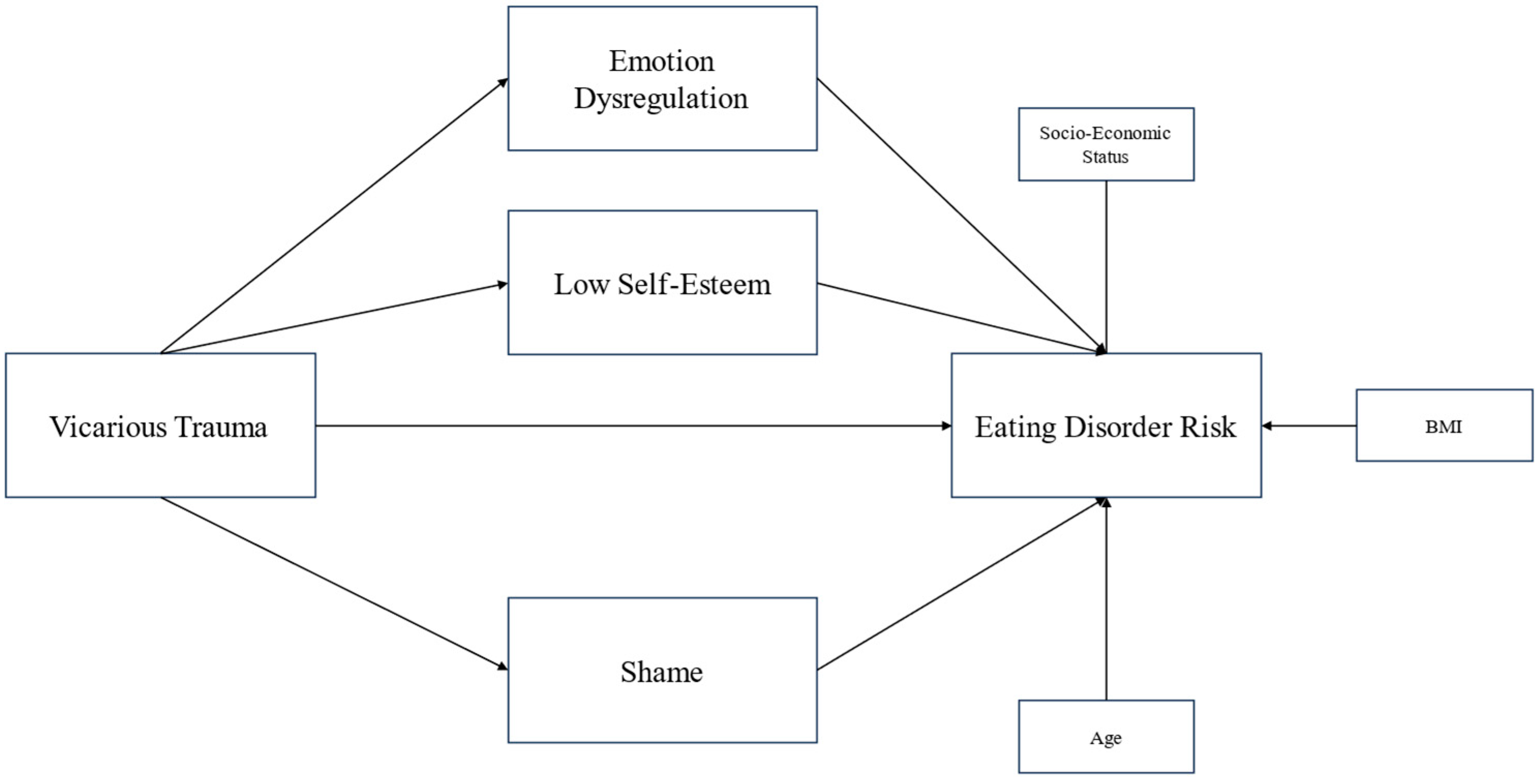

Hayes, 2022) was used for mediation analysis, employing Model 4. The vicarious trauma score was entered as the independent variable. The low self-esteem, emotion dysregulation, and shame scores were entered as parallel mediators. The EDRC score was entered as a dependent variable. Age, BMI, and socioeconomic status were entered as covariates, in accordance with the literature highlighting their influence on sexual identity, body image, and eating behaviors.

Data was checked for consistency with assumptions of linear regression through visual checking of P-P and Q-Q plots and through checking of the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Due to the violation of the multi-normality assumption, a heteroskedasticity-consistent estimator was selected in PROCESS (HC3;

Davidson & MacKinnon, 1993;

Hayes & Cai, 2007). Bootstrap estimation with 5000 samples was used to determine 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs); effects were considered significant when CIs did not include 0.

Subscale Reliability

To estimate the reliability of the employed subscales, McDonald’s ω (

McDonald, 2013) was computed using the OMEGA macro (

Hayes & Coutts, 2020) through forced single-factor maximum likelihood analysis. Computed values are available in

Table 1.

All employed subscales showed good or excellent reliability.

2.5. Missing Values

One value was missing regarding age, one value was missing regarding education status, and five values were missing regarding socioeconomic status. Due to the very small quantity of missing values, these were handled by replacing them with the sample’s median values.

4. Discussion

Most of the initial hypotheses of the study have been confirmed.

Vicarious trauma showed a significant direct effect on eating disorder risk, while two out of the three mediators highlighted partial mediation, coherently with the psychological mediation framework (

Hatzenbuehler, 2009). Only the hypothesis regarding shame acting as a mediator was not verified.

Distress related to vicarious trauma was very common in our sample (mean score of 24.7 out of a maximum detected range of 30), depicting it as a salient experience that is near-universal in the study participants. The mediation analysis highlighted its negative effects on several intrapsychic characteristics as well as eating disorder risk. As suggested in previous studies (

Herek et al., 1999;

Noelle, 2002;

Perry & Alvi, 2012), heterosexist experiences appear to have a negative effect on mental health even when experienced vicariously. In an international context in which LGBTQ+ people and LGBTQ+ rights are increasingly becoming the target of bias-motivated attacks and scapegoating by major political actors (

Guillot & Coi, 2025;

ILGA Europe, 2021), the experience of this type of minority stress is likely to trend further upwards and pose further risks to LGBTQ+ people’s health. This is particularly worrying for eating disorder risk in light of its mortality risk and health burden (

Van Hoeken & Hoek, 2020).

Witnessing heterosexist experiences may induce vicarious trauma in people who share the salient LGBTQ+ identity, evoking feelings of fear, helplessness, shock, and anger as well as the sensation of being potentially threatened (

Lannert, 2015;

Sullaway, 2004). Consistently with minority stress theory, these feelings would also add to the feeling of needing to hide one’s identity (

Meyer, 2003). These findings offer us additional interpretations for why it seems to increase emotion dysregulation in LGBTQ+ people. Emotion regulation capacity may be conceptualized as a potentially finite resource, which is depleted by having to frequently cope with negative affect linked to vicarious traumatization (i.e., “ego depletion”;

Inzlicht et al., 2006). This, in turn, may lead to a heightening of eating disorder risk when depleted early through minority stressors. Vicarious trauma also seems to lower people’s self-esteem level. This may be linked to perceiving part of oneself to be stigmatized and rejected by society, as well as through being part of a group at risk of minoritization and exclusion. In addition to being a known risk factor for eating disorders (

Colmsee et al., 2021;

Mora et al., 2017), self-esteem may be further impacted in LGBTQ+ people by minority stress through lower social support and isolation (

Closson & Comeau, 2021;

Taylor et al., 2022).

In our model, shame was not a significant mediator. Despite showing no significant multicollinearity when conducting the assumptions check for linear regression, it is possible that the lack of statistical significance of shame in the model is due to a high level of shared variance with low self-esteem. The two constructs may share a significant amount of overlap regarding negative self-evaluation. Shame is a powerful emotion that is strongly linked to beliefs about evaluations coming from others (i.e., external shame) or oneself (i.e., internal shame;

Goss & Allan, 2009). Shame proneness, as explored in this model, has been found to be an important aspect in eating disorder symptoms (

Nechita et al., 2021) due to its role in causing and maintaining disordered eating behaviors. It can additionally prevent help-seeking behaviors, which can further endanger health outcomes. Self-esteem similarly refers to a global or specific evaluation of the self, which can be positive or negative, highlighting a stable self-concept (

Rosenberg et al., 1995). It is possible that both may be important, as highlighted in previous studies, and that a study design able to assess each variable over time (i.e., longitudinal) would expose the role of shame in this process.

The significance of BMI, despite its limitations as a measure (e.g., lack of precision, inability to distinguish muscle from body fat), seems to have been confirmed—body dissatisfaction in particular has been reliably associated with weight status, of which BMI can be considered an imperfect proxy (

Goldfield et al., 2010). As in previous literature (

Rohde et al., 2017), age was also negatively related with eating disorder risk. The role of socioeconomic status was not significant, contrary to expectations from the literature which paints socioeconomic status as an important aspect in eating disorder risk, such as through the added stress of food insecurity and the way it shapes eating behaviors in people with low socioeconomic status (

Rasmusson et al., 2019). It is possible that this is due to the homogeneity of the current sample, which primarily comprises people who perceive themselves to be of either sufficient or comfortable (79.8%) socioeconomic status.

Finally, it should be noted that grouping results from many different LGBTQ+ identities, as was carried out in this model, may obscure their specificities and differences. Each specific identity may have differing relationships with some of the included variables. For example, trans and gender-diverse people may have a particular relationship with thinness and muscularity due to the link between body image ideals and gender congruence, as bodily experiences strongly influence eating-related challenges (

Santoniccolo et al., 2025).

4.1. Implications

The findings from this study further recontextualize heterosexism as a public health issue. As highlighted by international reports, Italy is lagging significantly behind in providing structural protections such as national laws against discrimination and hate crimes that involve sexual identity (

Equaldex, 2025;

ILGA Europe, 2025). Ideally, policies and structural protections should be put in place at the local, national, and international level that are aimed at preventing discrimination, violence, and stigma related to sexual orientation and gender identity, as they may protect the physical and mental health of LGBTQ+ people.

Previous studies on minority stress in the Italian context paint it as a prevalent, clinically relevant issue (

Priola et al., 2014;

Scandurra et al., 2017,

2020). Focusing on minority stress in clinical contexts has also been previously suggested to be a promising path (

Frost & Meyer, 2023;

Trombetta et al., 2024b,

2024c). Attempts have been made to develop treatments for disordered eating that are informed by minority stress theories with promising results: interventions may be aimed at strengthening resilience, conducting psychoeducation on minority stress, and promoting self-affirmation, while addressing body image concerns, dietary restraints, and affect regulation strategies (

Brown et al., 2024). Working on relevant mediators of this relationship—in this case, emotion dysregulation and low self-esteem—may also mitigate the effects of vicarious trauma. For example, interventions focusing on emotion dysregulation may attempt to reduce rumination, improve metacognition, and work on acceptance of unwanted emotions (

Leppanen et al., 2022). Additionally, interventions focusing on increasing self-esteem have been found to be effective in reducing eating disorder symptomatology (

Kästner et al., 2019)—exploring how minority stress may have affected self-esteem and providing affirming care regarding sexual orientation and gender identity could be useful in this regard.

Programs promoting knowledge and information around LGBTQ+ identities may also prove useful in reducing the spread of negativity and promote contexts that protect individuals’ health through being respectful of diversities in sexual orientation and gender identity (

Carpinelli et al., 2023).

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

The study uses self-report measures, which have known limitations such as socially desirable responding (

Allison & Heshka, 1993) or researcher acquiescence (

Paulhus, 1991). Body mass index computation could also have suffered from distortions in self-reporting of height and weight (

Krul et al., 2011).

The sample was also homogeneous in other sociodemographic characteristics, showing a young mean age, a relatively high level of education, and an overall sufficient socioeconomic status. As previously discussed (

Trombetta et al., 2024a), more research on sexual and gender minorities with more diverse samples would be necessary to confirm these relationships. The sample’s young mean age may limit generalizability to older LGBTQ+ people (i.e., people in late adulthood and older). Low socioeconomic status in particular may be an additional axis of intersectional analysis (

Crenshaw, 1991) and has previously been associated with higher chances of eating disorders in sexual and gender minorities (

Burke et al., 2023). The role of multiple marginalizations related to eating behaviors in LGBTQ+ people may merit further attention.

Although our use of a non-probability sampling method (snowball sampling) is an efficient—although biased—way to reach statistical minority populations, it could also limit the generalizability of our findings. Future studies could improve upon this aspect by using probability sampling to gather participants.

The employed measure for eating disorder risk is a general one, rather than a specific one. Given the differences in etiopathology for eating disorders (

Agras & Robinson, 2017), it may be interesting to explore these relationships in specific eating disorders (e.g., bulimia, anorexia) in future studies. Furthermore, employing a study design that uses a certified diagnosis as a dependent variable rather than general eating disorder risk may provide more precise estimations.

Additional studies on vicarious trauma would be needed to confirm these findings, as it remains a generally understudied facet of minority stress with limited existing evidence. Longitudinal studies in particular should be conducted to provide more reliable insights, as existing evidence is overwhelmingly cross-sectional (

Santoniccolo & Rollè, 2024). The generalizability of these results to people outside these characteristics should be interpreted with caution and should be confirmed through further studies. Conducting studies on these relationships on specific identities (e.g., gay, lesbian, or bisexual people, trans men and women, etc.) may further deepen the understanding of this phenomenon. Furthermore, conducting future studies with larger sample sizes may help provide more certainty to the study’s findings. Additionally, while the causal order of the variables was theoretically defined and appears logically sound, the cross-sectional nature of the study makes it ill-fitted to provide certainty in the order of causal relationships. Finally, qualitative studies—exceedingly rare in this field (

Santoniccolo & Rollè, 2024)—may prove useful in surveying in-depth the experiences of LGBTQ+ people regarding eating disorders and how they may be related to minority stress.