The Involvement of Academic and Emotional Support for Sustainable Use of MOOCs

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. MOOCs and MOOC Platforms: Definition, Importance, and Crisis Regarding Sustainable Development

1.2. The Involvement of Academic and Emotional Support: Gaps, Significance, and Research Focuses

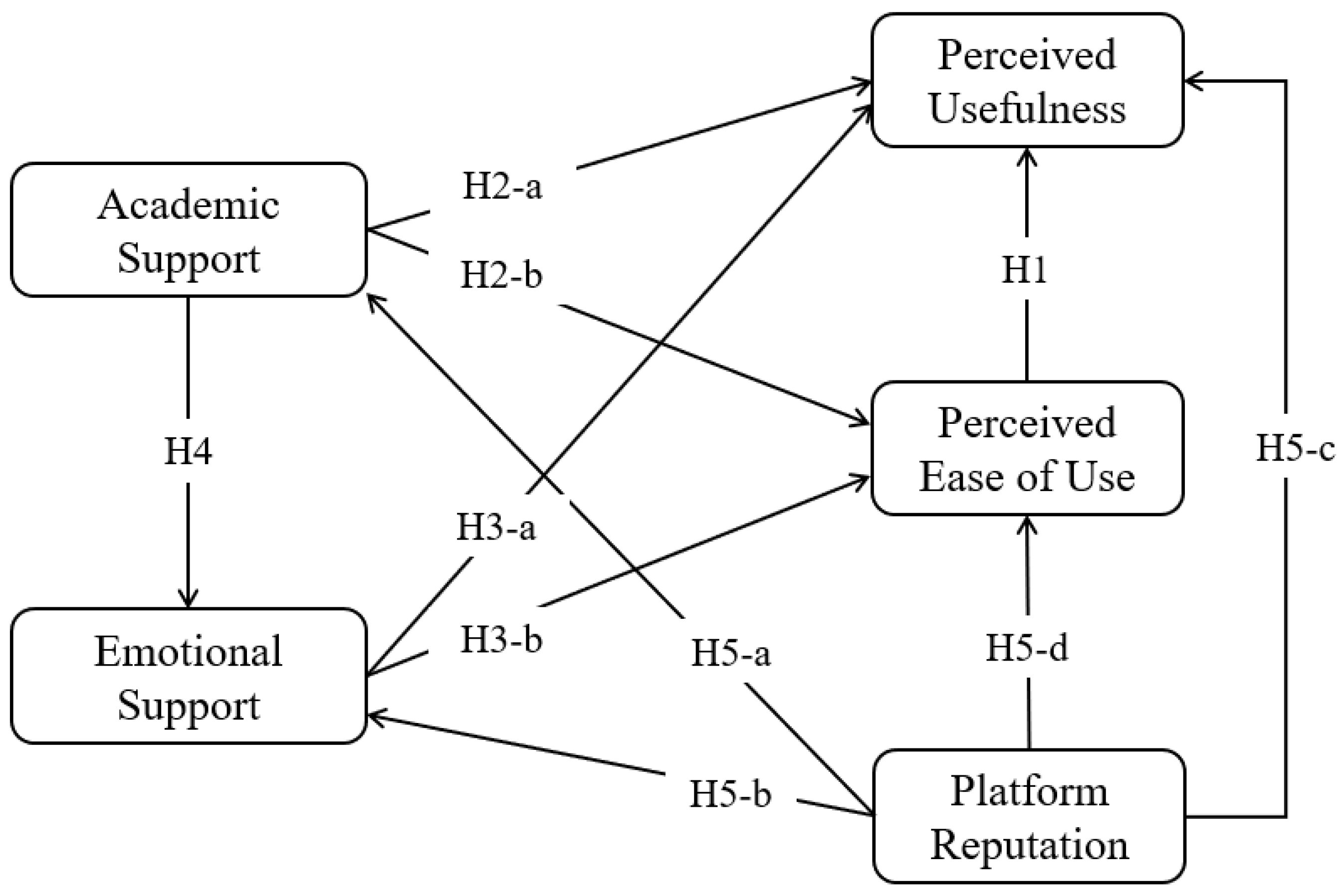

2. Literature and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Transitions: From xMOOCs, cMOOCs, to Wrapped MOOCs

2.2. MOOCs and Technology Acceptance

2.3. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and Technology Acceptance Intention

2.4. Academic Support in MOOC Learning

2.5. Emotional Support in MOOC Learning

2.6. Platform Reputation and Technology Acceptance

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Instrument

3.2. Data Collection and Participants

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.3. Model Fit

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiong, Y.; Ling, Q.; Li, X. Ubiquitous e-Teaching and e-Learning: China’s Massive Adoption of Online Education and Launching MOOCs Internationally during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2021, 2021, 6358976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, L.; Ren, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, K. Quantification and prediction of engagement: Applied to personalized course recommendation to reduce dropout in MOOCs. Inf. Process. Manag. 2024, 61, 103536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galikyan, I.; Admiraal, W.; Kester, L. MOOC discussion forums: The interplay of the cognitive and the social. Comput. Educ. 2021, 165, 104133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Sonnert, G.; Sadler, P.M.; Sasselov, D.D.; Fredericks, C.; Malan, D.J. Going over the cliff: MOOC dropout behavior at chapter transition. Distance Educ. 2020, 41, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, B.; Cagiltay, K. Did you act according to your intention? An analysis and exploration of intention–behavior gap in MOOCs. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 29, 1733–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldowah, H.; Al-Samarraie, H.; Alzahrani, A.I.; Alalwan, N. Factors affecting student dropout in MOOCs: A cause and effect decision-making model. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2020, 32, 429–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C. MOOC student dropout prediction model based on learning behavior features and parameter optimization. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 714–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Benckendorff, P.; Gannaway, D. Learner engagement in MOOCs: Scale development and validation. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatrafi, O.; Johri, A.; Rangwala, H. Needle in a haystack: Identifying learner posts that require urgent response in MOOC discussion forums. Comput. Educ. 2018, 118, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkova, K.; Shcheglova, I. Deconstructing self-regulated learning in MOOCs: In search of help-seeking mechanisms. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, M.; Watted, A.; Haick, H. Motivation to learn in massive open online courses: Examining aspects of language and social engagement. Comput. Educ. 2016, 94, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Jew, L.; Qi, D. Take a MOOC and then drop: A systematic review of MOOC engagement pattern and dropout factor. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Yahaya, N.; Alamri, M.M.; Alyoussef, I.Y.; Al-Rahmi, A.M.; Kamin, Y.B. Integrating innovation diffusion theory with technology acceptance model: Supporting students’ attitude towards using a massive open online courses (MOOCs) systems. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 29, 1380–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Chen, X. Continuance intention to use MOOCs: Integrating the technology acceptance model (TAM) and task technology fit (TTF) model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 67, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, D.; Fu, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Qu, X. Key characteristics in designing massive open online courses (MOOCs) for user acceptance: An application of the extended technology acceptance model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2022, 30, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.K. The behavioral intentions of Hong Kong primary teachers in adopting educational technology. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2016, 64, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreisiebner, S. Content and instructional design of MOOCs on information literacy: A comprehensive analysis of 11 xMOOCs. Inf. Learn. Sci. 2019, 120, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Liu, J.; Xu, X.; Kolletar-Zhu, K.; Zhang, Y. Effective interactive engagement strategies for MOOC forum discussion: A self-efficacy perspective. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0293668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H. Interactions in an xMOOC: Perspectives of learners who completed the course. Open Learn. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunar, A.S.; Abbasi, R.A.; Davis, H.C.; White, S.; Aljohani, N.R. Modelling MOOC learners’ social behaviours. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 107, 105835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, D.A.; Cho, M.-H. Use of a game-like application on a mobile device to improve accuracy in conjugating Spanish verbs. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2016, 29, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Montoya, M.-S.; Mena, J.; Rodríguez-Arroyo, J.A. In-service teachers’ self-perceptions of digital competence and OER use as determined by a xMOOC training course. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 77, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, V.H.; Singer, J. Learner experiences of a blended course incorporating a MOOC on Haskell functional programming. Res. Learn. Technol. 2019, 27, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eradze, M.; León Urrutia, M.; Reda, V.; Kerr, R. Blended learning with MOOCs: From investment effort to success: A systematic literature review on empirical evidence. In Proceedings of the 6th European MOOCs Stakeholders Summit, EMOOCs 2019, Naples, Italy, 20–22 May 2019; pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bruff, D.O.; Fisher, D.H.; McEwen, K.E.; Smith, B.E. Wrapping a MOOC: Student perceptions of an experiment in blended learning. J. Online Learn. Teach. 2013, 9, 187. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffer, T.; Govender, S.; Brown, C. “The best part was the contact!”: Understanding postgraduate students’ experiences of wrapped MOOCs. Open Prax. 2017, 9, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Brown, C.; O’Steen, B. Factors contributing to teachers’ acceptance intention of gamified learning tools in secondary schools: An exploratory study. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 6337–6363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. Factors contributing to teachers’ acceptance intention to gamified EFL tools: A scale development study. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2024, 72, 447–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mouakket, S. Factors influencing continuance intention to use social network sites: The Facebook case. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 53, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusilier, M.; Durlabhji, S. An exploration of student internet use in India. Campus-Wide Inf. Syst. 2005, 22, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. Determinants of the perceived usefulness (PU) in the context of using gamification for classroom-based ESL teaching: A scale development study. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 4741–4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. The effectiveness of gamified tools for foreign language learning (FLL): A systematic review. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-W. Online support service quality, online learning acceptance, and student satisfaction. Internet High. Educ. 2010, 13, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; O’Steen, B.; Brown, C. Flipped learning wheel (FLW): A framework and process design for flipped L2 writing classes. Smart Learn. Environ. 2020, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Hu, X.; Pan, Z.; Li, C.; Cai, Y.; Liu, M. Exploring the relationship between social presence and learners’ prestige in MOOC discussion forums using automated content analysis and social network analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 115, 106582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. Using eye-tracking technology to identify learning styles: Behaviour patterns and identification accuracy. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 4457–4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.; Fernández-Raga, M.; Osuna-Acedo, S.; Roura-Redondo, M.; Almazán-López, O.; Buldón-Olalla, A. Promoting Learners’ Voice Productions Using Chatbots as a Tool for Improving the Learning Process in a MOOC. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2019, 24, 545–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Lee, M.K. FAQ chatbot and inclusive learning in massive open online courses. Comput. Educ. 2022, 179, 104395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baha, T.A.; Hajji, M.E.; Es-Saady, Y.; Fadili, H. The impact of educational chatbot on student learning experience. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hew, K.F.; Huang, W.; Du, J.; Jia, C. Using chatbots to support student goal setting and social presence in fully online activities: Learner engagement and perceptions. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2022, 35, 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, M.M.; Upadhyaya, P.; Pillai, K.R. Intention and barriers to use MOOCs: An investigation among the post graduate students in India. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 5017–5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watted, A.; Barak, M. Motivating factors of MOOC completers: Comparing between university-affiliated students and general participants. Internet High. Educ. 2018, 37, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, D.A.; Frenay, M.; Swaen, V. The Learning Design of MOOC Discussion Forums: An Analysis of Forum Instructions and Their Role in Supporting the Social Construction of Knowledge. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2023, 59, 585–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Ye, L.; Hu, Z.; Lian, X. Exploring the impact of positive reappraisal on self-regulated learning in MOOCs: The mediating roles of control and value appraisals and positive emotion. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 152, 108070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, C.P.; Bowsher, J.; Maloney, J.P.; Lillis, P.P. Social support: A conceptual analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 25, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, H.B.; Lee, C.H.; Wyman Roth, N.E.; Li, K.; Çetinkaya-Rundel, M.; Canelas, D.A. Understanding the massive open online course (MOOC) student experience: An examination of attitudes, motivations, and barriers. Comput. Educ. 2017, 110, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; O’Steen, B.; Brown, C. The use of eye-tracking technology to identify visualisers and verbalisers: Accuracy and contributing factors. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2020, 17, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. Gamification for educational purposes: What are the factors contributing to varied effectiveness? Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 891–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.-K. Actionable Gamification: Beyond Points, Badges, and Leaderboards; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gillett-Swan, J.K. The challenges of online learning: Supporting and engaging the isolated learner. J. Learn. Des. 2017, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembylas, M. Adult learners’ emotions in online learning. Distance Educ. 2008, 29, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alraimi, K.M.; Zo, H.; Ciganek, A.P. Understanding the MOOCs continuance: The role of openness and reputation. Comput. Educ. 2015, 80, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tella, A.; Tsabedze, V.; Ngoaketsi, J.; Enakrire, R.T. Perceived Usefulness, Reputation, and Tutors’ Advocate as Predictors of MOOC Utilization by Distance Learners: Implication on Library Services in Distance Learning in Eswatini. J. Libr. Inf. Serv. Distance Learn. 2021, 15, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, L.; Brunner, B. Measuring public relationships among students and administrators at the University of Florida. J. Commun. Manag. 2002, 6, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, X. Research on technology adoption and promotion strategy of MOOC. In Proceedings of the 2015 6th IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science (ICSESS), Beijing, China, 23–25 September 2015; pp. 907–910. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M.; Koo, K. Emotional Presence in Building an Online Learning Community Among Non-traditional Graduate Students. Online Learn. 2020, 24, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Srinivasan, S.; Trail, T.; Lewis, D.; Lopez, S. Examining the relationship among student perception of support, course satisfaction, and learning outcomes in online learning. Internet High. Educ. 2011, 14, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Ferrin, D.L.; Rao, H.R. A trust-based consumer decision-making model in electronic commerce: The role of trust, perceived risk, and their antecedents. Decis. Support Syst. 2008, 44, 544–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revythi, A.; Tselios, N. Extension of technology acceptance model by using system usability scale to assess behavioral intention to use e-learning. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2019, 24, 2341–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jeyaraj, A. Information technology adoption and continuance: A longitudinal study of individuals’ behavioral intentions. Inf. Manag. 2013, 50, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Hong, Z.; Ren, C.; Zhang, W.; Xiang, F. What predicts patients’ adoption intention toward mHealth services in China: Empirical study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Scheel, L.; Vladova, G.; Ullrich, A. The influence of digital competences, self-organization, and independent learning abilities on students’ acceptance of digital learning. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2022, 19, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCann, C.; Jiang, Y.; Brown, L.E.; Double, K.S.; Bucich, M.; Minbashian, A. Emotional intelligence predicts academic performance: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Tan, X.; He, M.; Wu, X. The seewo interactive whiteboard (IWB) for ESL teaching: How useful it is? Heliyon 2023, 9, e20424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubovi, I. Cognitive and emotional engagement while learning with VR: The perspective of multimodal methodology. Comput. Educ. 2022, 183, 104495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, S.; Liu, Z.; Peng, X.; Yang, Z. Automated detection of emotional and cognitive engagement in MOOC discussions to predict learning achievement. Comput. Educ. 2022, 181, 104461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variable | Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 156 | 38 |

| Female | 254 | 62 | |

| Educational status | Undergraduate | 351 | 85.6 |

| Postgraduates | 59 | 14.4 | |

| Construct | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic support (AS) | 410 | 3.75 | 0.997 | −0.797 | 0.065 |

| Emotional support (ES) | 410 | 3.81 | 0.919 | −0.826 | 0.558 |

| Platform reputation (PR) | 410 | 4.01 | 0.849 | −1.035 | 1.208 |

| Perceived usefulness (PU) | 410 | 3.97 | 0.897 | −1.085 | 1.15 |

| Perceived ease of use (PEoU) | 410 | 3.81 | 0.893 | −0.69 | 0.27 |

| Construct | Item Code | Survey Item | Factor/Factor Loading | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Academic Support | AS1 | The instructor or peers give timely feedback on the assignments I submit to the MOOC platform. | 0.924 | ||||

| AS2 | I could ask questions regarding the course materials on the MOOC platform. | 0.906 | |||||

| AS3 | My peers on the MOOC platform are willing to provide academic help. | 0.880 | |||||

| Emotional Support | ES1 | The instructor encourages me to express my views in the coursework in MOOC study. | 0.888 | ||||

| ES2 | The instructor recognizes my completion of the MOOC courses. | 0.869 | |||||

| ES3 | The instructor gives me suggestions and advice that will help me build up confidence during my MOOC learning. | 0.895 | |||||

| Platform Reputation | PR1 | The MOOC platform has a high reputation. | 0.912 | ||||

| PR2 | The universities that offer courses on the MOOC platform have high reputation. | 0.830 | |||||

| PR3 | The MOOC platform is widely recognized. | 0.896 | |||||

| PR4 | The instructors teaching on the MOOC platform are widely recognized. | 0.832 | |||||

| Perceived Usefulness | PU1 | The MOOC platform provides me with more learning resources. | 0.839 | ||||

| PU2 | The MOOC platform increases my learning efficiency. | 0.904 | |||||

| PU3 | The MOOC platform makes my learning more convenient. | 0.864 | |||||

| Perceived Ease of Use | PEoU1 | It is easy to use MOOC platform for learning. | 0.834 | ||||

| PEoU2 | Overall, using the MOOC platform is simple. | 0.914 | |||||

| PEoU3 | I can quickly master the use of MOOC platform for learning. | 0.853 | |||||

| Total Variance Explained: 79.297% | 47.37% | 10.71% | 7.91% | 6.80% | 6.51% | ||

| Cronbach’s Alpha (α): 0.940 | 0.899 | 0.897 | 0.871 | 0.850 | 0.866 | ||

| AVE (Average Variance Extracted) | 0.754 | 0.817 | 0.782 | 0.752 | 0.756 | ||

| CR (Composite Reliability) | 0.924 | 0.93 | 0.915 | 0.901 | 0.903 | ||

| Construct | AVE | Square Root of AVE | Correlation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | ES | PR | PU | PEoU | |||

| Academic support (AS) | 0.817 | 0.904 | 1 | ||||

| Emotional support (ES) | 0.782 | 0.884 | 0.561 ** | 1 | |||

| Platform reputation (PR) | 0.754 | 0.868 | 0.492 ** | 0.467 ** | 1 | ||

| Perceived usefulness (PU) | 0.756 | 0.869 | 0.485 ** | 0.441 ** | 0.599 ** | 1 | |

| Perceived ease of use (PEoU) | 0.752 | 0.868 | 0.450 ** | 0.399 ** | 0.528 ** | 0.508 ** | 1 |

| Model Fit Index | Benchmark | Result | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbreviation | Full Form | Terrible | Acceptable | Excellent | Value | Interpretation |

| CMIN/df | Chi-Square to Degrees of Freedom Ratio | ≥5 | ≥3 | ≥1 | 1.851 | Excellent |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index | ≤0.90 | <0.95 | ≥0.95 | 0.981 | Excellent |

| GFI | Goodness-of-fit Index | n/a | ≥0.90 | ≥0.95 | 0.951 | Excellent |

| AGFI | Adjusted Goodness-of-fit Index | n/a | n/a | ≥0.90 | 0.929 | Excellent |

| NFI | Normalized Fit Index | <0.80 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.95 | 0.960 | Excellent |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index | n/a | n/a | ≥0.95 | 0.976 | Excellent |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation | ≥0.08 | >0.06 | ≤0.06 | 0.046 | Excellent |

| # | Hypothesis | Hypothesized Path | Estimate | p-Value | Hypothesis Testing Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Sig. | |||||

| 1 | H1 | PeoU → PU | 0.209 | 0.000 | *** | Supported |

| 2 | H2-a | AS → PU | 0.127 | 0.015 | * | Supported |

| 3 | H2-b | AS → PEoU | 0.189 | 0.002 | ** | Supported |

| 4 | H3-a | ES → PU | 0.080 | 0.160 | 0.160 | Unsupported |

| 5 | H3-b | ES → PEoU | 0.099 | 0.136 | 0.136 | Unsupported |

| 6 | H4 | AS → ES | 0.443 | 0.000 | *** | Supported |

| 7 | H5-a | PR → AS | 0.672 | 0.000 | *** | Supported |

| 8 | H5-b | PR → ES | 0.283 | 0.000 | *** | Supported |

| 9 | H5-c | PR → PU | 0.427 | 0.000 | *** | Supported |

| 10 | H5-d | PR → PEoU | 0.469 | 0.000 | *** | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, Z.; Li, H. The Involvement of Academic and Emotional Support for Sustainable Use of MOOCs. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060461

Luo Z, Li H. The Involvement of Academic and Emotional Support for Sustainable Use of MOOCs. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(6):461. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060461

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Zhanni, and Huazhen Li. 2024. "The Involvement of Academic and Emotional Support for Sustainable Use of MOOCs" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 6: 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060461

APA StyleLuo, Z., & Li, H. (2024). The Involvement of Academic and Emotional Support for Sustainable Use of MOOCs. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060461