Effects and Side Effects in a Short Work Coaching for Participants with and without Mental Illness

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Effects of Individual Work Coaching

1.2. Participants with and without Mental Illness in Coaching

1.3. Unwanted Events and Side Effects in Coaching

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Questions

- Which topics are dealt with in coaching with participants with mental illness as compared to participants without mental illness?

- How do work ability, impairments in work-relevant capacities, and work-related coping behavior change pre–post three coaching sessions and two weeks after in participants without mental illness as compared to participants with mental illness?

- How do the coach and the participants (with and without mental illness) rate the degree of coaching goal attainment?

- Which unwanted events occur in coaching participants with and without mental illness, and how often do they occur?

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Work-Related Coaching

2.4. Evaluation

2.4.1. Work Ability Index (WAI [91])

2.4.2. Mini-ICF-APP-S [95]

2.4.3. Inventory for Job Coping [104]

2.4.4. Coaching Goal Attainment [105]

2.4.5. Unwanted Events/Adverse Treatment Reactions Scale [75]

2.5. Sample Description

3. Results

3.1. Coaching Topics in Employees with and without Mental Illness

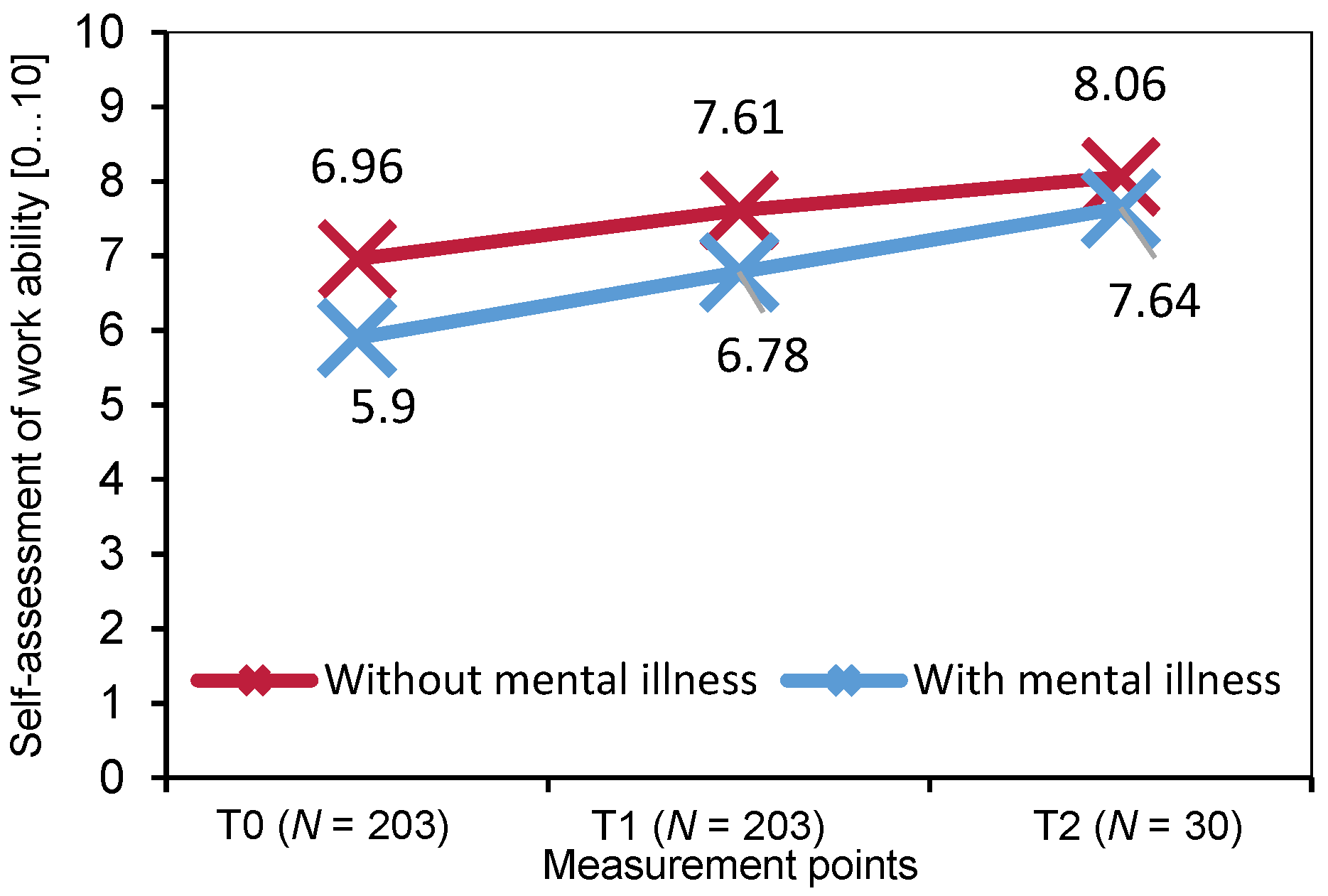

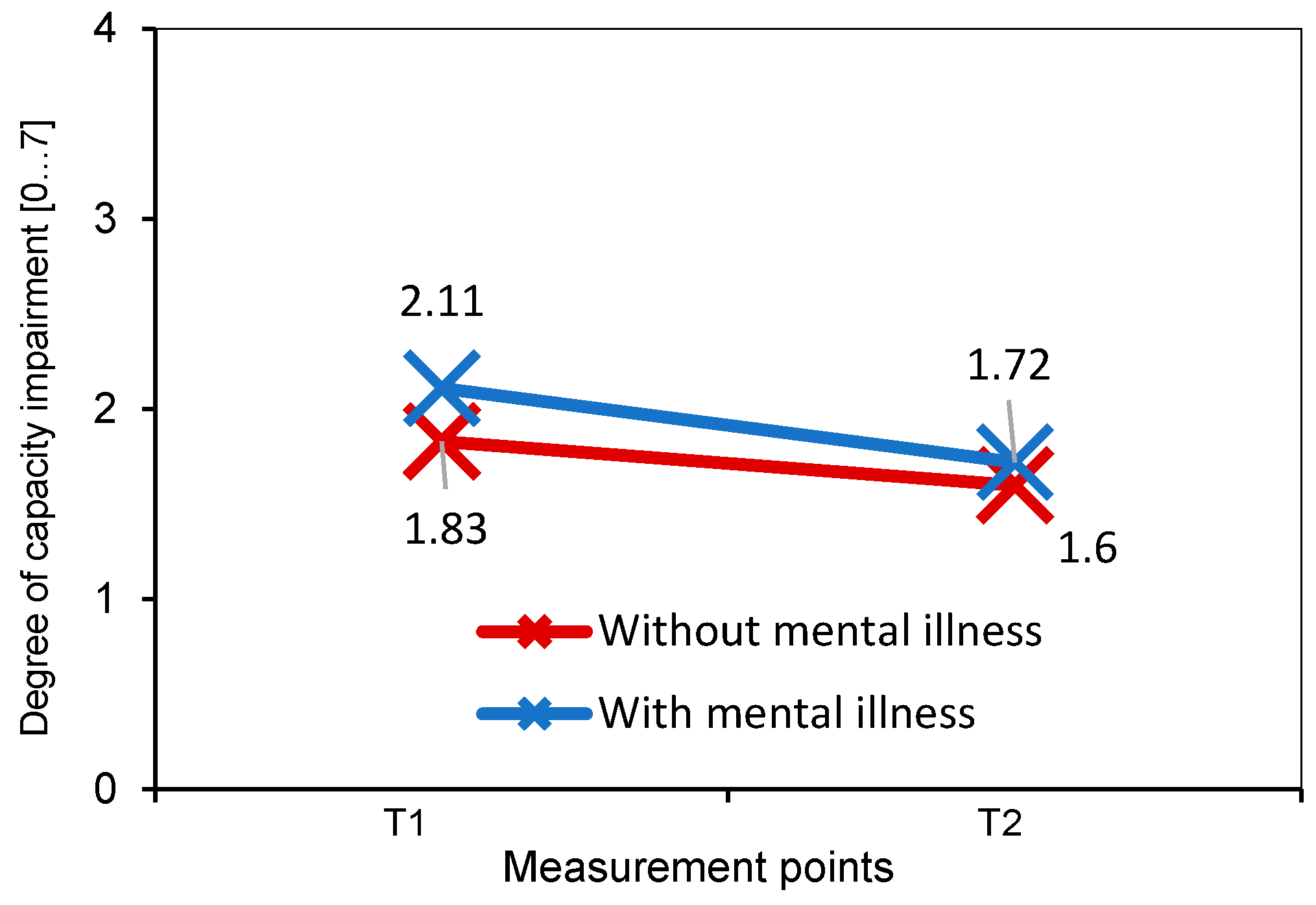

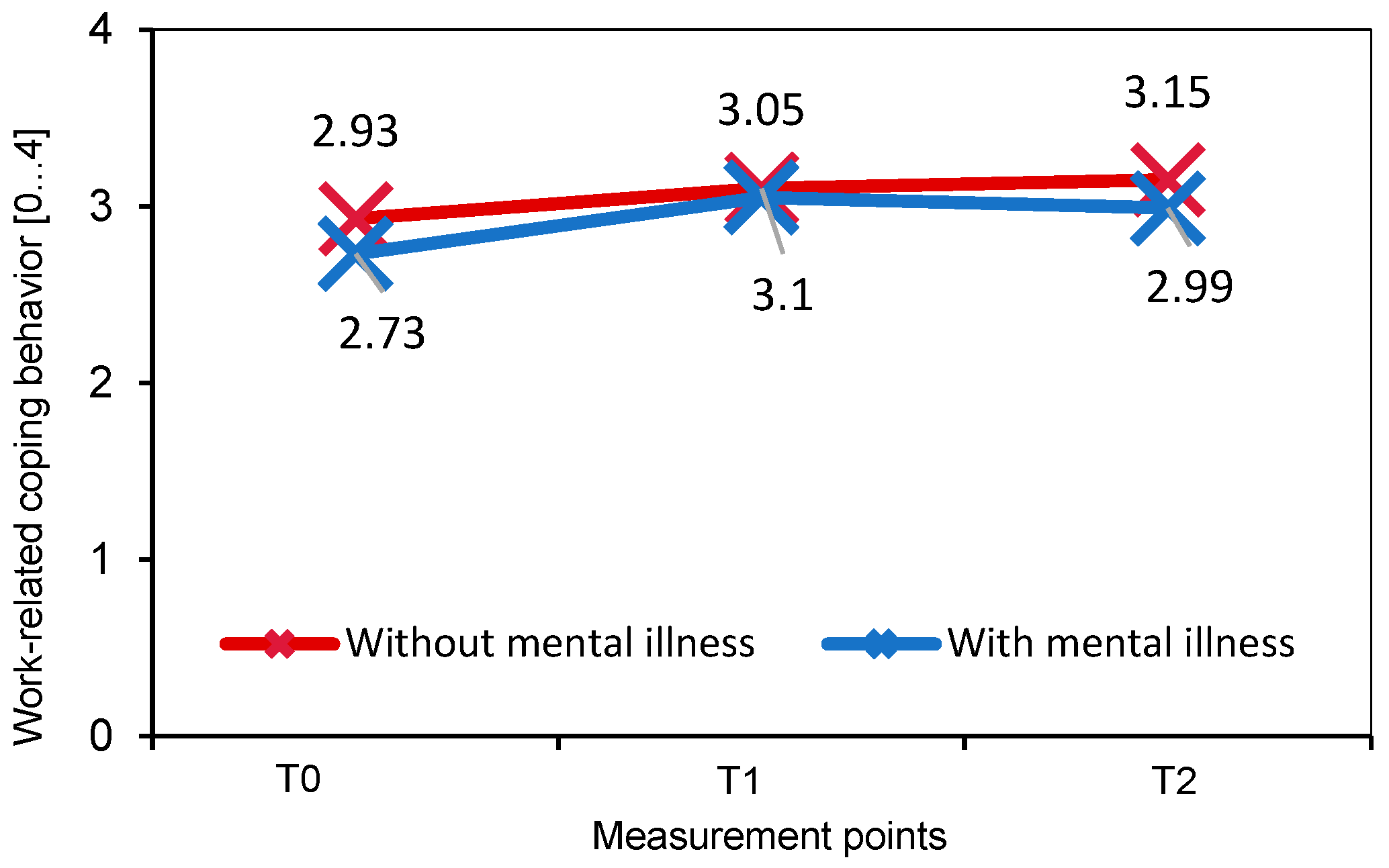

3.2. Change in Work-Related Resources Pre–Post Coaching and Two Weeks after the Third Coaching Session

3.3. Coaching Goal Attainment

3.4. Unwanted Events in Coaching

4. Discussion

4.1. Coaching Topics

4.2. Effects of Coaching

4.3. Side Effects

4.4. Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Loeb, C.; Stempel, C.; Isaksson, K. Social and emotional self-efficacy at work. Scand. J. Psychol. 2016, 57, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, M.; Hansson, L.; Ahlqvist, C. The importance of work as compared to other forms of daily occupations for wellbeing and functioning among persons with long-term mental illness. Community Ment. Health J. 2004, 40, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, J.R. Person-Job Fit: A Conceptual Integration, Literature Review, and Methodological Critique; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.C.; Yu, C.; Yi, C.C. The effects of positive affect, person-job fit, and well-being on job performance. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2014, 42, 1537–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, T. Person-organization fit and person-job fit in employee selection: A review of the literature. Osaka Keidai Ronshu 2004, 54, 179–196. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M.T.; Latif, W.; Naseer, W. The impact of person job fit on job satisfaction and its subsequent impact on employees performance. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 523–530. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Mao, C. The impact of person–job fit on job satisfaction: The mediator role of Self efficacy. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 121, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, N.; Noyan, A.; Ertosun, Ö.G. Linking person-job fit to job stress: The mediating effect of perceived person-organization fit. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 207, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgiç, A. The effects of person-job fit and person-organization fit on turnover intention: The mediation effect of job resourcefulness. J. Gastron. Hosp. Travel 2022, 5, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P.; Inceoglu, I. Job engagement, job satisfaction, and contrasting associations with person–job fit. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilmarinen, J.; von Bonsdorff, M. Work Ability; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tengland, P.A. The concept of work ability. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2011, 21, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattori, F.; Zisman-Ilani, Y.; Chmielowska, M.; Rodríguez-Martín, B. Measures of Shared Decision Making for People with Mental Disorders and Limited Decisional Capacity: A Systematic Review. Psychiatr. Serv. 2023, 74, 1171–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisker, J.; Hjorthøj, C.; Hellström, L.; Mundy, S.S.; Rosenberg, N.G.; Eplov, L.F. Predictors of return to work for people on sick leave with common mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2022, 95, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Follmer, K.B.; Jones, K.S. Mental illness in the workplace: An interdisciplinary review and organizational research agenda. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 325–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gühne, U.; Pabst, A.; Löbner, M.; Breilmann, J.; Hasan, A.; Falkai, P.; Kilian, R.; Allgöwer, A.; Ajayi, K.; Baumgärtner, J.; et al. Employment status and desire for work in severe mental illness: Results from an observational, cross-sectional study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpov, B.; Joffe, G.; Aaltonen, K.; Suvisaari, J.; Baryshnikov, I.; Näätänen, P.; Koivisto, M.; Melartin, T.; Oksanen, J.; Suominen, K.; et al. Level of functioning, perceived work ability, and work status among psychiatric patients with major mental disorders. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 44, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancman, S.; Barroso, B.I.D.L. Mental health: Professional rehabilitation and the return to work—A systematic review. Work 2021, 69, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linden, M. Definition and assessment of disability in mental disorders under the perspective of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Behav. Sci. Law 2017, 35, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosado-Solomon, E.H.; Koopmann, J.; Lee, W.; Cronin, M.A. Mental health and mental illness in organizations: A review, comparison, and extension. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2023, 17, 751–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.O.; Finne, L.B.; Garde, A.H.; Nielsen, M.B.; Sørensen, K.; Vleeshouwes, J. The Influence of Digitalization and New Technologies on Psychosocial Work Environment and Employee Health: A Literature Review; STAMI-Rapport: Oslo, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Creagh, S.; Thompson, G.; Mockler, N.; Stacey, M.; Hogan, A. Workload, work intensification and time poverty for teachers and school leaders: A systematic research synthesis. Educ. Rev. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadnejad, F.; Freeman, S.; Klassen-Ross, T.; Hemingway, D.; Banner, D. Impacts of Technology Use on the Workload of Registered Nurses: A Scoping Review. J. Rehab. Assist. Technol. Eng. 2023, 10, 2055–6683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrul, R.N.; Zainal, V.R.; Hakim, A. Workload, Work Stress, and Employee Performance: A literature Review. Dinasti Int. J. Educ. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2023, 4, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.G.; Frechette, M. The impact of workload, productivity, and social support on burnout among marketing faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Mark. Educ. 2022, 44, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reio, T.G., Jr.; Sutton, F.C. Employer assessment of work-related competencies and workplace adaptation. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2006, 17, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muschalla, B.; Linden, M. Capacity Limitations and Workplace Problems in Patients with Mental Disorders. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchberger, B.; Heymann, R.; Huppertz, H.; Friepörtner, K.; Pomorin, N.; Wasem, J. The effectiveness of interventions in workplace health promotion as to maintain the working capacity of health care personal. GMS Health Technol. Assess. 2011, 7, 1861–8863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakman, J.; Neupane, S.; Proper, K.I.; Kinsman, N.; Nygård, C.H. Workplace interventions to improve work ability: A systematic review and meta-analysis of their effectiveness. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health. 2018, 44, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlosser, A.; Shanan, Y. Fostering Soft Skills in Active Labor Market Programs: Evidence from a Large-Scale RCT; CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP17055; Centre for Economic Policy Research: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sundstrup, E.; Jakobsen, M.D.; Brandt, M.; Jay, K.; Persson, R.; Aagaard, P.; Andersen, L.L. Workplace strength training prevents deterioration of work ability among workers with chronic pain and work disability: A randomized controlled trial. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2014, 40, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarro, L.; Llauradó, E.; Ulldemolins, G.; Hermoso, P.; Solà, R. Effectiveness of workplace interventions for improving absenteeism, productivity, and work ability of employees: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackman, A.; Moscardo, G.; Gray, D.E. Challenges for the theory and practice of business coaching: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2016, 15, 459–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozer, G.; Jones, R.J. Understanding the factors that determine workplace coaching effectiveness: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 27, 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, E.; Nilsson, V.O. What can we know about the effectiveness of coaching? a meta-analysis based only on randomized controlled trials. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2023, 22, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez Zuberbuhler, J.; Corbu, A.; Christensen, M.; Salanova, M. The effectiveness of positive psychological coaching at work: A systematic review. Coaching 2024, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, M.; Buckley, A. The Complete Handbook of Coaching; Cox, E., Bachkirova, T., Clutterbuck, D., Eds.; Sage: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; SECTION III; Chapter 29; pp. 405–417. [Google Scholar]

- Compton, M.T.; Shim, R.S. Mental illness prevention and mental health promotion: When, who, and how. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 981–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrie, K.; Joyce, S.; Tan, L.; Henderson, M.; Johnson, A.; Nguyen, H.; Modini, M.; Groth, M.; Glozier, N.; Harvey, S.B. A framework to create more participants without mental illness workplaces: A viewpoint. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2018, 52, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.J.; Woods, S.A.; Guillaume, Y.R. The effectiveness of workplace coaching: A meta-analysis of learning and performance outcomes from coaching. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 89, 249–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theeboom, T.; Beersma, B.; van Vianen, A.E. Does coaching work? A meta-analysis on the effects of coaching on individual level outcomes in an organizational context. J. Posit. Psychol. 2014, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lai, Y.L.; Xu, X.; McDowall, A. The effectiveness of workplace coaching: A meta-analysis of contemporary psychologically informed coaching approaches. J. Work-Appl. Manag. 2021, 14, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.; Furnham, A. Coaching as a developmental intervention in organisations: A systematic review of its effectiveness and the mechanisms underlying it. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cidral, W.; Berg, C.H.; Paulino, M.L. Determinants of coaching success: A systematic review. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2021, 72, 753–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, B.; Grove, J.R.; Beauchamp, M.R. Relational efficacy beliefs and relationship quality within coach-athlete dyads. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2010, 27, 1035–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, R.H.; Kim, S.; Resua, K.A. The effects of coaching with video and email feedback on preservice teachers’ use of recommended practices. Top. Early Child Spec. Educ. 2019, 38, 192–203. [Google Scholar]

- Jowett, S. Coaching effectiveness: The coach–athlete relationship at its heart. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 16, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, J.A.; McCombs, J.S.; Martorell, F. Reading coach quality: Findings from Florida middle schools. Lit. Res. Instr. 2012, 51, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raver, C.C.; Jones, S.M.; Li-Grining, C.P.; Metzger, M.; Champion, K.M.; Sardin, L. Improving preschool classroom processes: Preliminary findings from a randomized trial implemented in Head Start settings. Early Child. Res. Q. 2008, 23, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Y.; McDowall, A. A systematic review (SR) of coaching psychology: Focusing on the attributes of effective coaching psychologists. Int. Coach. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 9, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riediger, M. Procrastination as a coaching topic. Organ. Superv. Coach. 2016, 23, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarborough, J.P. The role of coaching in leadership development. New Dir. Stud. Leadersh. 2018, 158, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemisiou, M.A. The effectiveness of person-centered coaching intervention in raising emotional and social intelligence competencies in the workplace. Int. Coach. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 13, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaap, P.; Dippenaar, M. The impact of coaching on the emotional and social intelligence competencies of leaders. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2017, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oosten, E.B.; McBride-Walker, S.M.; Taylor, S.N. Investing in what matters: The impact of emotional and social competency development and executive coaching on leader outcomes. Consul. Psychol. J. 2019, 71, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T.; Morrow, D.; Miller, M.R. From Aha to Ta-dah: Insights during life coaching and the link to behaviour change. Coaching 2018, 11, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, M.; Douglas, S.; Butler, D. Developing coaching mindset and skills. Manag. Teach. Rev. 2021, 6, 330–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, M. Evidence-Based Coaching Volume 1: Theory, Research and Practice from the Behavioural Sciences; Cavanagh, M., Grant, A.M., Kemp, T., Eds.; Australian Academic Press: Queensland, Australia, 2005; Chapter 3; pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, H. Mental Disorders in Coaching. In International Handbook of Evidence-Based Coaching: Theory, Research and Practice; Greif, S., Möller, H., Scholl, W., Passmore, J., Müller, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2022; Chapter 16; pp. 577–586. [Google Scholar]

- APA. APA Dictionary of Psychology. Psychotherapy; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Greif, S. Coaching und Ergebnisorientierte Selbstreflexion: Theorie, Forschung und Praxis des Einzel-und Gruppencoachings; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2008; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, W.W.; Martins, S.S.; Nestadt, G.; Bienvenu, O.J.; Clarke, D.; Alexandre, P. The burden of mental disorders. Epidemiol. Rev. 2008, 30, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, K.; Maliske, L.; Böckler, A.; Kanske, P. Social impairments in mental disorders: Recent developments in studying the mechanisms of interactive behavior. Clin. Psychol. Eur. 2019, 1, e33143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.; Oades, L.; Grant, A.M. An Evaluation of a Life-Coaching Group Program: Initial Findings From a Waitlist Control Study. In Evidence-Based Coaching (Volume 1): Contributions from the Behavioural Sciences; Grant, A.M., Cavanagh, M.J., Kemp, T., Eds.; Australian Academic Press: Queensland, Australia, 2004; Chapter 4; pp. 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, G.B.; Grant, A.M. Positive Psychology Coaching in Practice. In Evidence-Based Coaching (Volume 1): Contributions from the Behavioural Sciences; Grant, A.M., Cavanagh, M.J., Kemp, T., Eds.; Australian Academic Press: Queensland, Australia, 2004; Chapter 8; pp. 143–158. [Google Scholar]

- Aboujaoude, E. Where life coaching ends and therapy begins: Toward a less confusing treatment landscape. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 15, 973–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, A.M.; Green, R.M. Developing clarity on the coaching-counseling conundrum: Implications for counsellors and psychotherapists. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2018, 18, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. A Languishing–Flourishing Model of Goal Striving and Mental Health for Coaching Populations. In Coaching Researched: A Coaching Psychology Reader; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, T. The SAGE Handbook of Coaching; Bachkirova, T., Spence, G., Drake, D., Eds.; Sage: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Schermuly, C.C. Qualität im Coaching; Triebler, C., Heller, B., Hauser, A., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016; pp. 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Berglas, S. The very real dangers of executive coaching. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Werk, L.P.; Muschalla, B. Coaching bei Erschöpfung und Überarbeitungsgefühlen. ASU Arbeitsmedizin Sozialmedizin Umweltmed. 2022, 57, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.; Livingstone, J.B. Coaching vs psychotherapy in health and wellness: Overlap, dissimilarities, and the potential for collaboration. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2013, 2, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauß, B.; Linden, M. Risks and Side Effects of Psychotherapy. PPmP Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2018, 68, 375–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, M. How to Define, Find and Classify Side Effects in Psychotherapy: From Unwanted Events to Adverse Treatment Reactions. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2013, 20, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berk, M.; Parker, G. The elephant on the couch: Side effects of psychotherapy. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2009, 43, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linden, M.; Schermuly-Haupt, M.L. Definition, assessment and rate of psychotherapy side effects. World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilburg, R.R. Executive Coaching: Practices and Perspectives; Fitzgerald, C., Berger, J.G., Eds.; Davis-Black: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 283–301. [Google Scholar]

- Schermuly, C.C.; Schermuly-Haupt, M.L.; Schölmerich, F.; Rauterberg, H. Zu Risiken und Nebenwirkungen lesen Sie…–Negative Effekte von Coaching. Z. Arb. Organ. 2014, 58, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA. Internet-mediated psychological services and the American Psychological Association ethics code. Psychotherapy 2003, 40, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muschalla, B.; Müller, J.; Grocholewski, A.; Linden, M. Talking about Side Effects in Psychotherapy Did Not Impair the Therapeutic Alliance in an Experimental Study. Psychother. Psychosom. 2022, 91, 360–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermuly, C.C.; Graßmann, C. A literature review on negative effects of coaching–what we know and what we need to know. Coaching 2019, 12, 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermuly, C.C.; Bohnhardt, F.A. Und wer coacht die Coaches? Organ. Superv. Coach. 2014, 21, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oellerich, K. Negative Effekte von Coaching und ihre Ursachen aus der Perspektive der Organisation. Organ. Superv. Coach. 2016, 23, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graßmann, C.; Schermuly, C.C. The role of neuroticism and supervision in the relationship between negative effects for clients and novice coaches. Coaching 2018, 11, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graßmann, C.; Schermuly, C.C. Side effects of business coaching and their predictors from the coachees’ perspective. J. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 15, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M.; Giusino, D.; Nielsen, K.; Aboagye, E.; Christensen, M.; Innstrand, S.T.; Mazzetti, G.; Heuvel, M.v.D.; Sijbom, R.B.; Pelzer, V.; et al. H-work project: Multilevel interventions to promote mental health in smes and public workplaces. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hautzinger, M. Verhaltensmodifikation und ihre Bedeutung im Coaching; Greif, S., Möller, H., Scholl, W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 621–630. [Google Scholar]

- Werk, L.P.; Laskowski, N.M.; Naujoks, M.; Muschalla, B. Chose one—Act on one! A Three Session Coaching on a Selected Work Problem. Psychosoz. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 36, 81–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, M.; Hautzinger, M. Verhaltenstherapiemanual–Erwachsene; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tuomi, K.; Ilmarinen, J.; Eskelinen, L.; Järvinen, E.; Toikkanen, J.; Klockars, M. Work Ability Index; Finnish Institute of Occupational Health: Helsinki, Finnland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselhorn, H.M.; Freude, G. Der Work Ability Index. Ein Leitfaden; Schriftenreihe der Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin: Sonderschrift; Verlag für neue Wissenschaft: Bremerhaven, Germany, 2007; Volume 87. [Google Scholar]

- Freyer, M. Eine Konstruktvalidierung des Work Ability Index Anhand Einer Repräsentativen Stichprobe von Erwerbstätigen in Deutschland; Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin: Hannover, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlstrom, L.; Grimby-Ekman, A.; Hagberg, M.; Dellve, L. The work ability index and single-item question: Associations with sick leave, symptoms, and health—A prospective study of women on long-term sick leave. Scand J. Work Environ. Health 2010, 36, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linden, M.; Keller, L.; Noack, N.; Muschalla, B. Self-rating of capacity limitations in mental disorders: The “Mini-ICF-APP-S”. Prax. Klin. Verhal. Rehabil. 2018, 101, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Balestrieri, M.; Isola, M.; Bonn, R.; Tam, T.; Vio, A.; Linden, M.; Maso, E. Validation of the Italian version of Mini-ICF-APP, a short instrument for rating activity and participation restrictions in psychiatric disorders. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2013, 22, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burri, M.; Werk, L.P.; Berchtold, A.; Pugliese, M.; Muschalla, B. Mini-ICF-APP Inter-Rater Reliability and Development of Capacity Disorders Over the Course of a Vocational Training Program—A Longitudinal Study. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. Ment. Health 2021, 8, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molodynski, A.; Linden, M.; Juckel, G.; Yeeles, K.; Anderson, C.; Vazquez-Montes, M.; Burns, T. The reliability, validity, and applicability of an English language version of the Mini-ICF-APP. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013, 48, 1347–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AWMF. Leitlinie zur Begutachtung bei Psychischen und Psychosomatischen Störungen; Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften: Frankfurt, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund (DRV). Leitlinien für die Sozialmedizinische Begutachtung. In Sozialmedizinische Beurteilung bei Psychischen und Verhaltensstörungen; Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund: Hannover, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- SGVP. Qualitätsleitlinien für Versicherungspsychiatrische Gutachten; Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Versicherungspsychiatrie: Bern, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: http://www.iv-pro-medico.ch/fileadmin/documents/D_Qualitaetsleitlinien_fuer_versicherungspsychiatrische_Gutachten_20.10.2016.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2016).

- Linden, M.; Baron, S.; Muschalla, B. Mini-ICF-Rating für Aktivitäts-und Partizipationsstörungen bei Psychischen Erkrankungen (Mini-ICF-APP); Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, S.T.; Weniger, G.; Bobes, J.; Seifritz, E.; Vetter, S. Exploring the factor structure of the mini-ICF-APP in an inpatient clinical sample, according to the psychiatric diagnosis. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2021, 14, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muschalla, B. Work-anxiety coping intervention improves work-coping perception while a recreational intervention leads to deterioration. Results from a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 26, 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner-Stokes, L. Goal attainment scaling (GAS) in rehabilitation: A practical guide. Clin. Rehab. 2009, 23, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, G.T. There’s a S.M.A.R.T. Way to Write Management’s Goals and Objectives. Manag. Rev. 1981, 70, 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bovend’Eerdt, T.J.; Dawes, H.; Izadi, H.; Wade, D.T. Agreement between two different scoring procedures for goal attainment scaling is low. J. Rehabil. Med. 2011, 43, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockwood, K.; Joyce, B.; Stolee, P. Use of goal attainment scaling in measuring clinically important change in cognitive rehabilitation patients. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1997, 50, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenbeek, D.; Ketelaar, M.; Lindeman, E.; Galama, K.; Gorter, J.W. Interrater reliability of goal attainment scaling in rehabilitation of children with cerebral palsy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 91, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasny-Pacini, A.; Hiebel, J.; Pauly, F.; Godon, S.; Chevignard, M. Goal attainment scaling in rehabilitation: A literature-based update. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2013, 56, 212–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linden, M. Nebenwirkungsmanagement. In Verhaltenstherapiemanual Erwachsene; Linden, M., Hautzinger, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Chapter 6; pp. 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, C.C.; Chang, C.H.; Djurdjevic, E.; Eatough, E. Occupational stressors and job performance: An updated review and recommendations. New Dev. Theor. Concept. Approaches Job Stress 2010, 8, 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muschalla, B.; Linden, M. Different workplace-related strains and different workplace-related anxieties in different professions. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2013, 55, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touloumakos, A.K. Expanded yet restricted: A mini review of the soft skills literature. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipskaya-Velikovsky, L.; Elgerisi, D.; Easterbrook, A.; Ratzon, N.Z. Motor skills, cognition, and work performance of people with severe mental illness. Disab. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 1396–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennekam, S.; Follmer, K.; Beatty, J. Exploring mental illness in the workplace: The role of HR professionals and processes. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 3135–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duijts, S.F.A.P.; Kant, I.P.; van den Brandt, P.A.P.; Swaen, G.M.H.P. Effectiveness of a preventive coaching intervention for employees at risk for sickness absence due to psychosocial health complaints: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2008, 50, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J. Stress in the workplace: A coaching approach. Work 2007, 28, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lange, M.; Petermann, F. Die Wirksamkeit von Einzel-und Gruppentherapie im Vergleich. Eine systematische Literaturanalyse. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Kurortmed. 2013, 23, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losch, S.; Traut-Mattausch, E.; Mühlberger, M.D.; Jonas, E. Comparing the effectiveness of individual coaching, self-coaching, and group training: How leadership makes the difference. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hautzinger, M. Depressionen. In Verhaltenstherapiemanual Erwachsene; Linden, M., Hautzinger, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Chapter 100; pp. 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehmer, K.R.; Barakat, S.; Ahn, S.; Prokop, L.J.; Erwin, P.J.; Murad, M.H. Health coaching interventions for persons with chronic conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. System. Rev. 2016, 5, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, C.C.; Morgan, D.N. Literacy leadership: The importance of soft skills. Read. Teach. 2018, 72, 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, B.J. Wanted: Soft skills for today’s jobs. Phi Delta Kappan 2017, 98, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edlund, M.J.; Wang, J.; Brown, K.G.; Forman-Hoffman, V.L.; Calvin, S.L.; Hedden, S.L.; Bose, J. Which mental disorders are associated with the greatest impairment in functioning? Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 1265–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, M. Fähigkeitsbeeinträchtigungen und Teilhabeeinschränkungen. Bundesgesundheitsblatt 2016, 59, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessnitzer, S.; Kauffeld, S. The working alliance in coaching: Why behavior is the key to success. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2015, 51, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greif, S.; Möller, H.; Scholl, W.; Passmore, J.; Müller, F. Coaching Definitions and Concepts. In International Handbook of Evidence-Based Coaching: Theory, Research and Practice; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2022; Chapter 1; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt, C. The inner conflict “individuation vs. dependency” in coaching: Key findings from a qualitative study on experienced coaches’ practice. Organ. Superv. Coach. 2021, 28, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| T0 | T1 | T2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Session: Behavior Analysis | 2. Session: Training | 3. Session: Reflection | Two Weeks after Third Session |

| Work ability (WAI) Capacity impairment (Mini-ICF-APP-S) Job coping (JoCoRi) | WAI Mini-ICF-APP-S JoCoRi Side effects | WAI JoCoRi |

| Participants without Mental Illness | Participants with Mental Illness | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Average age in years | 40.41 | 13.05 | 46.06 | 12.00 |

| n = 103 | % | n = 100 | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 77 | 75 | 80 | 80 |

| Male | 26 | 25 | 20 | 20 |

| Professional fields | ||||

| Office | 33 | 32 | 29 | 29 |

| Service | 31 | 30 | 27 | 27 |

| Education and research | 26 | 25 | 20 | 20 |

| Healthcare | 9 | 9 | 18 | 18 |

| Production | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| Coaching topics | ||||

| Role stressors | 7 | 6.5 | 4 | 4 |

| Workload | 34 | 33 | 33 | 33 |

| Situational constraints | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Lack of control | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Interpersonal demands | 37 | 36 | 37 | 37 |

| Careers issues | 13 | 12.5 | 10 | 10 |

| Job conditions | 3 | 3 | 9 | 9 |

| Acute stressors | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Participants without Mental Illness (n = 103) | Participants with Mental Illness (n = 100) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goal Attainment—Participants | n | % | n | % |

| Much less than expected | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Less than expected | 10 | 10 | 3 | 3 |

| Expected result | 62 | 60 | 67 | 67 |

| More than expected | 29 | 28 | 27 | 27 |

| Much more than expected | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Goal Attainment—Coach | n | % | n | % |

| Much less than expected | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Less than expected | 2 | 2 | 24 | 24 |

| Expected result | 13 | 13 | 57 | 57 |

| More than expected | 71 | 69 | 16 | 16 |

| Much more than expected | 17 | 16 | 1 | 1 |

| Participants without Mental Illness (n = 103) | Participants with Mental Illness (n = 100) | χ2-Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unwanted Events | n | % | n | % | p |

| No unwanted events occurred | 41 | 40 | 33 | 33 | 0.781 |

| Worsening of existing complaints | 16 | 15.5 | 15 | 15 | 0.885 |

| Occurrence of new complaints | 16 | 15.5 | 16 | 16 | 0.817 |

| Aggravation of problems | 21 | 20 | 23 | 23 | 0.626 |

| Dependence on the coach | 4 | 4 | 20 | 20 | <0.001 |

| Discomfort during coaching sessions | 7 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 0.527 |

| Problems with coaching requirements | 6 | 6 | 10 | 10 | 0.296 |

| Problems with the coach | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.738 |

| Problems in partnership and family | 9 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 0.799 |

| Problems with friends, neighbors, or others | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0.913 |

| Problems at work | 26 | 25 | 22 | 22 | 0.901 |

| Dissatisfaction with coaching result so far | 6 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0.211 |

| More sessions needed | 15 | 14.5 | 24 | 24 | 0.106 |

| Other negative developments in life | 31 | 30 | 14 | 14 | 0.044 |

| Problems with third-party comments | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.668 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Werk, L.P.; Muschalla, B. Effects and Side Effects in a Short Work Coaching for Participants with and without Mental Illness. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060462

Werk LP, Muschalla B. Effects and Side Effects in a Short Work Coaching for Participants with and without Mental Illness. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(6):462. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060462

Chicago/Turabian StyleWerk, Lilly Paulin, and Beate Muschalla. 2024. "Effects and Side Effects in a Short Work Coaching for Participants with and without Mental Illness" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 6: 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060462

APA StyleWerk, L. P., & Muschalla, B. (2024). Effects and Side Effects in a Short Work Coaching for Participants with and without Mental Illness. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060462