Teachers’ Punishment Intensity and Student Observer Trust: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Punishment Intensity and Observer Trust

1.2. Trustworthiness as a Potential Mediator

1.3. Group Relationship as a Potential Moderator

2. Method

2.1. Experimental Design and Participant

2.2. Experimental Procedure and Materials

2.2.1. Basic Demographic Variables

2.2.2. Hypothetical Punishment Scenario

2.2.3. Manipulation Checks

2.2.4. Social Evaluations of the Punisher

2.3. Data Analysis

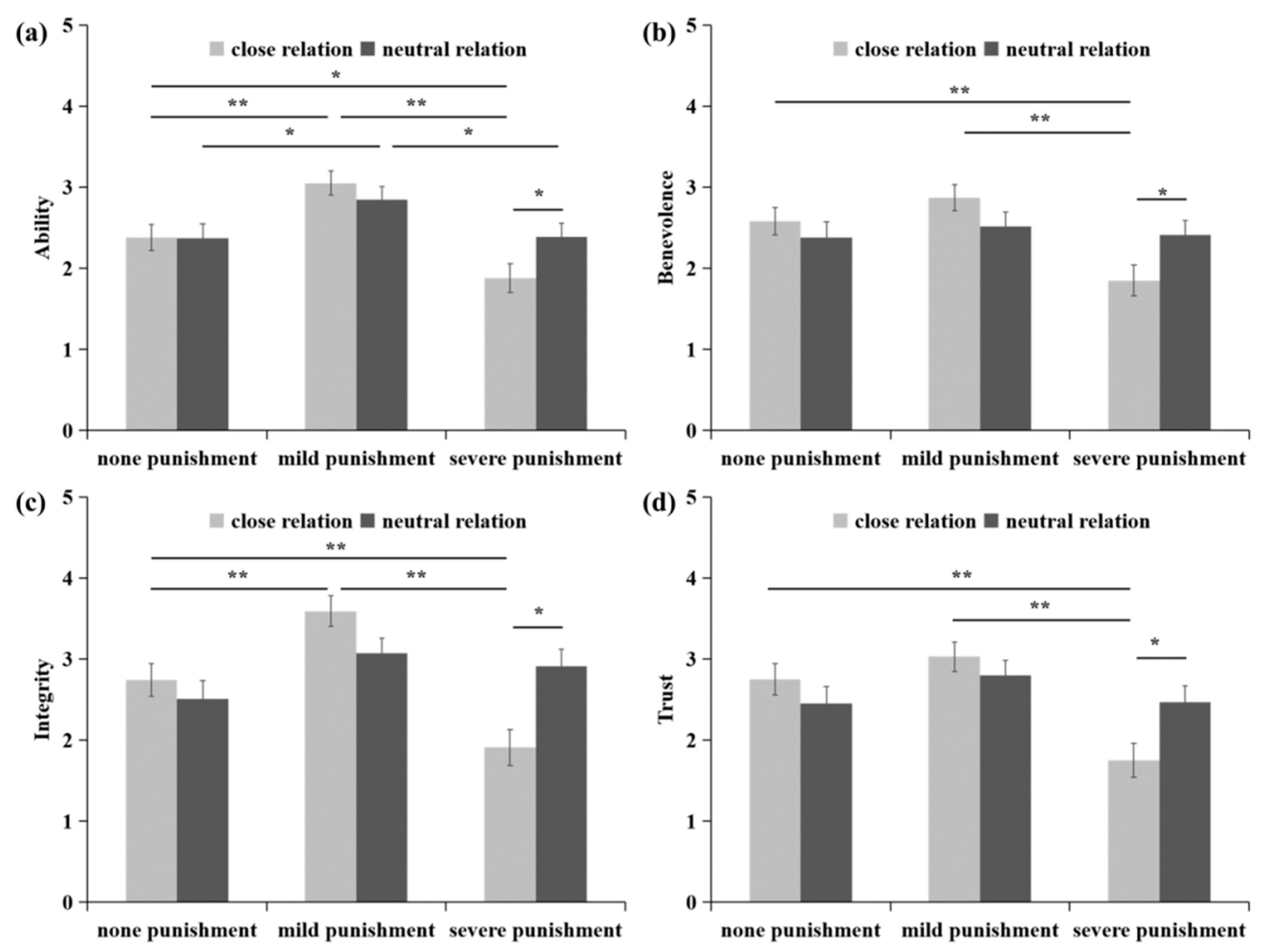

3. Results

3.1. Manipulation Check

3.2. Preliminary Analyses

3.3. Moderated Mediation Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Punishment Intensity and Adolescent Observer Trust

4.2. The Mediating Role of Trustworthiness

4.3. The Moderating Effect of the Group Relationship

5. Educational Suggestions

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, L.; Murnighan, J.K. The dynamics of punishment and trust. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 1385–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, J.; Li, D.; Papanikolaou, D. Trust, collaboration, and economic growth. Manag. Sci. 2021, 67, 1825–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, F.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A. Toward a model of interpersonal trust drawn from neuroscience, psychology, and economics. Trends Neurosci. 2019, 42, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesen, P.T.; Schaeffer, M.; Sønderskov, K.M. Ethnic diversity and social trust: A narrative and meta-analytical review. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2020, 23, 441–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, K.T.; de Jong, B. Trust within the workplace: A review of two waves of research and a glimpse of the third. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2022, 9, 247–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedlich, S.; Kallfaß, A.; Pohle, S.; Bormann, I. A comprehensive view of trust in education: Conclusions from a systematic literature review. Rev. Educ. 2021, 9, 124–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M. Trust and risk perception: A critical review of the literature. Risk Anal. 2021, 41, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, D.; Anderson, J.E.; Schlösser, T.; Ehlebracht, D.; Fetchenhauer, D. Trust at zero acquaintance: More a matter of respect than expectation of reward. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 107, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, R.; Javor, A. The biology of trust: Integrating evidence from genetics, endocrinology, and functional brain imaging. J. Neurosci. Psychol. Econ. 2012, 5, 63–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgis, P.; Brunton-Smith, I.; Jackson, J. Trust in science, social consensus and vaccine confidence. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 1528–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinschenk, A.C.; Dawes, C.T. The genetic and psychological underpinnings of generalized social trust. J. Trust Res. 2019, 9, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.J.; Hoffman, M.; Bloom, P.; Rand, D.G. Third-party punishment as a costly signal of trustworthiness. Nature 2016, 530, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, S.; Jeffery, L.; Palermo, R.; Collova, J.R.; Sutherland, C.A.M. Children’s dynamic use of face- and behavior-based cues in an economic trust game. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 58, 2275–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, J.C.; Jimenez-Leal, W. Severity and deservedness determine signalled trustworthiness in third party punishment. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 63, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G.C. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc. 2018, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towner, E.; Chierchia, G.; Blakemore, S.J. Sensitivity and specificity in affective and social learning in adolescence. Trends Cogn. Neurosci. 2023, 27, 642–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.J.; Mills, K.L. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Dong, M.C.; Zhu, X. Learn to be good or bad? Revisited observer effects of punishment: Curvilinear relationship and network contingencies. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 34, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooijman, M.; Graham, J. Unjust punishment in organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 2018, 38, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Scott, B.A.; LePine, J.A. Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 909–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiatt, M.S.; Lowman, G.H.; Maloni, M.; Swaim, J.; Veliyath, R. Ability, benevolence, and integrity: The strong link between student trust in their professors and satisfaction. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2023, 21, 100768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling theory: A review and assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.T.; Gu, F.F.; Dong, M.C. Observer effects of punishment in a distribution network. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 50, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, J.A.; Faber, N.S.; Crockett, M. Preferences and beliefs in ingroup favoritism. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 126656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Liu, Q.; Chen, C.; Qi, C. Group membership and adolescents’ third-party punishment: A moderated chain mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1251276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cikara, M.; Van Bavel, J.J. The neuroscience of intergroup relations: An integrative review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 9, 245–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qi, C.H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, X.X.; Gao, X.L. In-group favoritism or the black sheep effect? Group bias of fairness norm enforcement during economic games. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 28, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuliffe, K.; Dunham, Y. Group bias in cooperative norm enforcement. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2016, 371, 20150073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, A.; Purić, D.; Krstić, K. Does parochial cooperation exist in childhood and adolescence? A meta-analysis. Int. J. Psychol. 2021, 56, 917–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloor, J.L.; Okimoto, T.G.; Li, X.; Gazdag, B.A.; Ryan, M.K. How identity impacts bystander responses to workplace mistreatment. J. Manag. 2023, 01492063231177976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, R.M.; Kleiman-Weiner, M.; Young, L. What we owe to family: The impact of special obligations on moral judgment. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Jin, L.; Yue, G.; Ren, Z. Is a punisher always trustworthy? in-group punishment reduces trust. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 22965–22975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H. The effect of the performance appraisal system on trust for management: A field quasi-experiment. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keri, S.; Kiss, I.; Kelemen, O. Sharing secrets: Oxytocin and trust in schizophrenia. Soc. Neurosci. 2009, 4, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, Z.; Shaw, A. Secret to friendship: Children make inferences about friendship based on secret sharing. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 2139–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Amos: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed.; Multivariate applications series; Routledge; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-138-79702-4. [Google Scholar]

- Darley, J.M. Morality in the law: The psychological foundations of citizens’ desires to punish transgressions. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 2009, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, H.W.; Xiong, J.P.; Zhao, H.; Liu, R.X.; Qi, C.H. Psychological development mechanism of in-group favoritism during fairness norm enforcement. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 29, 2091–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara-Ettinger, J.; Gweon, H.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Schulz, L.E. Children’s understanding of the costs and rewards underlying rational action. Cognition 2015, 140, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, T. Discrimination in the laboratory: A meta-analysis of economics experiments. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2016, 90, 375–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Punishment intensity | 0.98 | 0.79 | - | ||||

| 2. Group relationship | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.07 | - | |||

| 3. Ability | 2.53 | 1.10 | −0.08 | 0.03 | - | ||

| 4. Benevolence | 2.47 | 1.15 | −0.11 | −0.02 | 0.59 ** | - | |

| 5. Integrity | 2.84 | 1.39 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.67 ** | 0.63 ** | - |

| 6. Trust | 2.59 | 1.28 | −0.15 * | 0.01 | 0.61 ** | 0.68 ** | 0.70 ** |

| Regression Equation | Helmet Coding a | Indicator Coding b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result Variable | Prediction Variable | β | t | 95% CI | β | t | 95% CI |

| Trustworthiness | D1 | 0.10 | 0.84 | [−0.14 0.34] | 0.40 | 2.85 ** | [0.13 0.69] |

| D2 | −0.61 | −4.80 ** | [−0.87 −0.38] | −0.20 | −1.57 | [−0.47 0.05] | |

| W | 0.03 | 0.50 | [−0.07 0.13] | −0.06 | −0.57 | [−0.26 0.14] | |

| D1 × W | 0.13 | 1.07 | [−0.09 0.37] | −0.09 | −0.66 | [−0.34 0.18] | |

| D2 × W | 0.42 | 3.75 ** | [0.21 0.65] | 0.34 | 2.57 * | [0.09 0.61] | |

| Trust | D1 | −0.18 | −1.88 | [−0.38 0.01] | −0.21 | −1.90 | [−0.42 0.01] |

| D2 | 0.05 | 0.47 | [−0.14 0.25] | −0.16 | −1.46 | [−0.37 0.06] | |

| W | −0.01 | −0.07 | [−0.09 0.07] | −0.05 | −0.59 | [−0.24 0.12] | |

| D1 × W | 0.07 | 0.74 | [−0.12 0.28] | 0.13 | 1.16 | [−0.09 0.34] | |

| D2 × W | −0.10 | −1.01 | [−0.30 0.10] | 0.02 | 0.20 | [−0.21 0.25] | |

| Trustworthiness | 1.12 | 10.45 ** | [0.92 1.33] | 1.12 | 10.47 ** | [0.92 1.33] | |

| Mediator Variable | Prediction Variable | Moderator Variable | Helmet Coding a | Indicator Coding b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | 95% CI | β | t | 95% CI | |||

| Trustworthiness | D1 | close | −0.03 | −0.17 | [−0.36 0.29] | 0.55 | 2.85 | [0.18 0.93] |

| D1 | neutral | 0.25 | 1.20 | [−0.17 0.66] | 0.35 | 1.55 | [−0.09 0.79] | |

| D2 | close | −1.15 | −6.02 ** | [−1.53 −0.78] | −0.60 | −3.25 ** | [−0.99 −0.25] | |

| D2 | neutral | −0.20 | −1.12 | [−0.57 0.15] | 0.15 | 0.66 | [−0.30 0.60] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Qi, C. Teachers’ Punishment Intensity and Student Observer Trust: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060471

Zhang Z, Qi C. Teachers’ Punishment Intensity and Student Observer Trust: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(6):471. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060471

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhen, and Chunhui Qi. 2024. "Teachers’ Punishment Intensity and Student Observer Trust: A Moderated Mediation Model" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 6: 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060471

APA StyleZhang, Z., & Qi, C. (2024). Teachers’ Punishment Intensity and Student Observer Trust: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060471