Persistence of Soil Water Repellency After the 2022 Bolt Creek Fire

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Site and Instrumentation

2.2. Field and Laboratory Testing

3. Results and Discussion

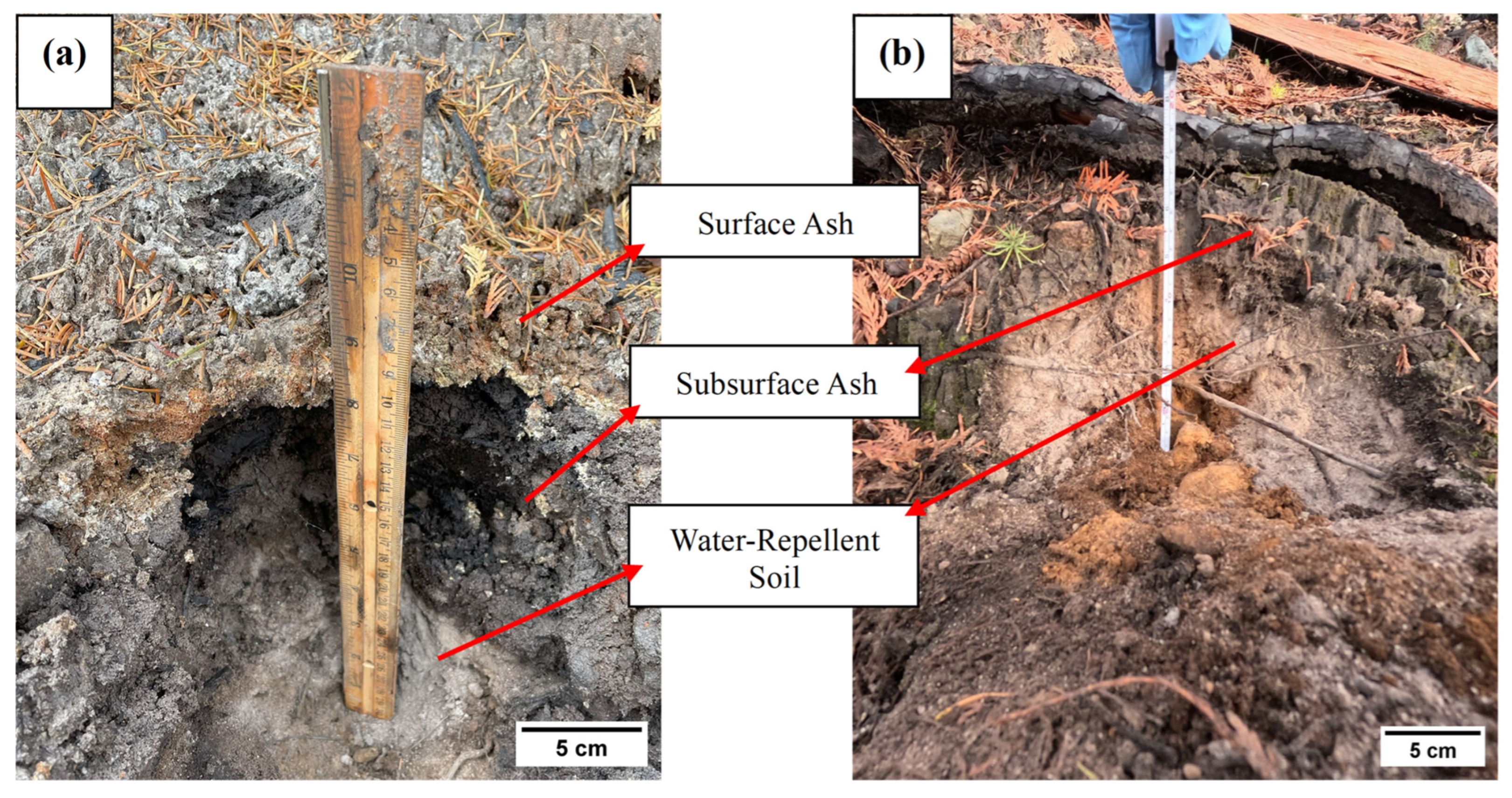

3.1. Soil and Ash Characterization

3.2. Hydraulic Behavior

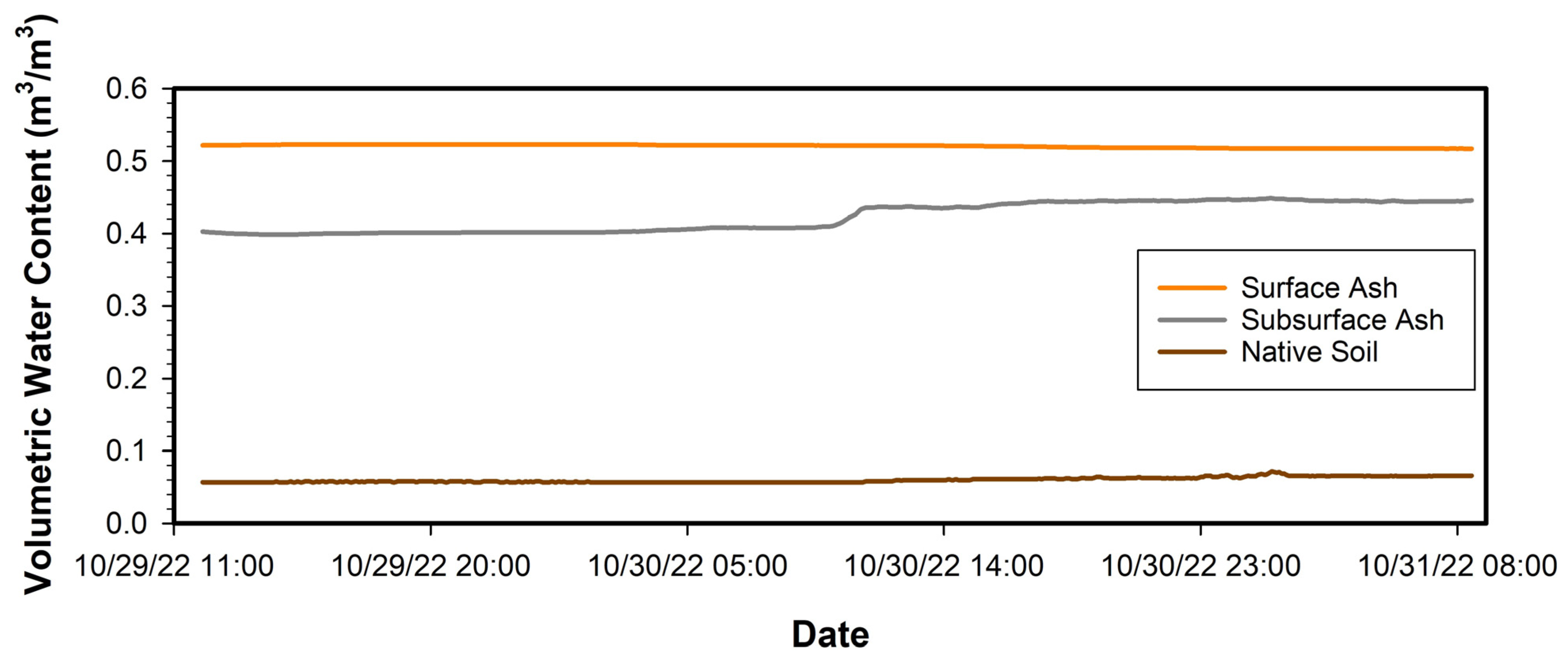

3.3. Short-Term Water Content Trends of Ash and Soil

3.4. Long-Term Water Content Trends of Ash and Soil

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gabet, E.J.; Bookter, A. Physical, chemical and hydrological properties of Ponderosa pine ash. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2011, 20, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, C.; Santín, C.; Neris, J.; Sigmund, G.; Otero, X.L.; Manley, J.; González-Rodríguez, G.; Belcher, C.M.; Cerdá, A.; Marcotte, A.L.; et al. Chemical characteristics of wildfire ash across the globe and their environmental and socio-economic implications. Environ. Int. 2023, 178, 108065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodí, M.B.; Martin, D.A.; Balfour, V.N.; Santín, C.; Doerr, S.H.; Pereira, P.; Cerdà, A.; Mataix-Solera, J. Wildland fire ash: Production, composition and eco-hydro-geomorphic effects. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2014, 130, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santín, C.; Doerr, S.H.; Otero, X.L.; Chafer, C.J. Quantity, composition and water contamination potential of ash produced under different wildfire severities. Environ. Res. 2015, 142, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodela, M.H.; Chowdhury, I.; Hohner, A.K. Emerging investigator series: Physicochemical properties of wildfire ash and implications for particle stability in surface waters. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2022, 24, 2129–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabet, E.J.; Sternberg, P. The effects of vegetative ash on infiltration capacity, sediment transport, and the generation of progressively bulked debris flows. Geomorphology 2008, 101, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, S.W.; Balfour, V.N. The effects of soil texture and ash thickness on the post-fire hydrological response from ash-covered soils. J. Hydrol. 2010, 393, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.A.; Wu, J.Q.; Robichaud, P.R. Assessing burn severity and comparing soil water repellency, Hayman Fire, Colorado. Hydrol. Process. 2005, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, M.E.; Benito, E.; De Blas, E. Impact of wildfires on surface water repellency in soils of northwest Spain. Hydrol. Process. 2005, 19, 3649–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robichaud, P.R.; Wagenbrenner, J.W.; Pierson, F.B.; Spaeth, K.E.; Ashmun, L.E.; Moffet, C.A. Infiltration and interrill erosion rates after a wildfire in western Montana, USA. Catena 2016, 142, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; McGuire, K.J.; Stewart, R.D. Effect of soil water-repellent layer depth on post-wildfire hydrological processes. Hydrol. Process. 2019, 34, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBano, L.F. The role of fire and soil heating on water repellency in wildland environments: A review. J. Hydrol. 2000, 232, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, S.M. Mechanism of fire-induced water repellency in soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1974, 38, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, L.W.; Jacobsen, O.H.; Moldrup, P. Soil water repellency: Effects of water content, temperature, and particle size. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1999, 63, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Alleres, M.; Varela, M.E.; Benito, E. Natural severity of water repellency in pine forest soils from NW Spain and influence of wildfire severity on its persistence. Geoderma 2012, 191, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebel, B.A.; Moody, J.A.; Martin, D.A. Hydrologic conditions controlling runoff generation immediately after wildfire. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48, W03529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Robichaud, P.R.; Hohner, A.K.; Akin, I.D. Evaluating Polymeric Additives for Post-Wildfire Erosion Reduction with Indoor Rainfall Simulation. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2025, 43, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Hohner, A.K.; Robichaud, P.R.; Akin, I.D. Effects of post-wildfire erosion and wildfire ash on water quality. In Proceedings of the 9th International Congress on Environmental Geotechnics, Chania, Greece, 25–28 June 2023; pp. 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerr, S.H.; Shakesby, R.A.; Walsh, R.P.D. Soil water repellency: Its causes, characteristics and hydro-geomorphological significance. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2000, 51, 33–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, J.A.; Ebel, B.A. Hyper-dry conditions provide new insights into the cause of extreme floods after wildfire. Catena 2012, 93, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, I.D.; Akinleye, T.O. Water vapor sorption behavior of wildfire-burnt soil. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 2021, 147, 04021115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, I.D.; Likos, W.J. Brazilian tensile strength testing of compacted clay. Geotech. Test. J. 2017, 40, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reneau, S.L.; Katzman, D.; Kuyumjian, G.A.; Lavine, A.; Malmon, D.V. Sediment delivery after a wildfire. Geology 2007, 35, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdà, A.; Doerr, S.H. The effect of ash and needle cover on surface runoff and erosion in the immediate post-fire period. Catena 2008, 74, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Úbeda, X.; Martin, D.; Mataix-Solera, J.; Cerdà, A.; Burguet, M. Wildfire effects on extractable elements in ash from a Pinus pinaster forest in Portugal. Hydrol. Process. 2013, 28, 3681–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topoliantz, S.; Ponge, J.-F.; Lavelle, P. Humus components and biogenic structures under tropical slash-and-burn agriculture. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2006, 57, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topoliantz, S.; Ponge, J.-F. Charcoal consumption and casting activity by Pontoscolex corethrurus (Glossoscolecidae). Appl. Soil Ecol. 2005, 28, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, S.W.; Balfour, V.N. The effect of ash on runoff and erosion after a severe forest wildfire, Montana, USA. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2008, 17, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoof, C.R.; Wesseling, J.G.; Ritsema, C.J. Effects of fire and ash on soil water retention. Geoderma 2010, 159, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodí, M.B.; Doerr, S.H.; Cerdà, A.; Mataix-Solera, J. Hydrological effects of a layer of vegetation ash on underlying wettable and water repellent soil. Geoderma 2012, 191, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoof, C.R.; Gevaert, A.I.; Baver, C.; Hassanpour, B.; Morales, V.L.; Zhang, W.; Martin, D.; Giri, S.K.; Steenhuis, T.S. Can pore-clogging by ash explain post-fire runoff? Int. J. Wildland Fire 2016, 25, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, I.D.; Akinleye, T.O.; Robichaud, P.R. Changes in soil properties over time after a wildfire and implications to slope stability. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 2023, 149, 04023045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, Z.; Cerdà, A. Soil water repellency and plant cover: A state-of-knowledge review. Catena 2023, 229, 107213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, E.L.; MacDonald, L.H.; Stednick, J.D. Strength and persistence of fire-induced soil hydrophobicity under ponderosa and lodgepole pine, Colorado Front Range. Hydrol. Process. 2001, 15, 2877–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, A.; Robichaud, P.R.; Lewis, S.A.; Napper, C.; Clark, J. Field Guide for Mapping Post-Fire Soil Burn Severity; General Technical Report; RMRS-GTR-243; Rocky Mountain Research Station, US Department of Agriculture Forest Service: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2010; 49p.

- Agee, J.K. Fire Ecology of Pacific Northwest Forests; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D6913; Standard Test Methods for Particle-Size Distribution (Gradation) of Soils Using Sieve Analysis. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D7928; Standard Test Method for Particle-Size Distribution (Gradation) of Fine-Grained Soils Using the Sedimentation (Hydrometer) Analysis. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D4318; Standard Test Methods for Liquid Limit, Plastic Limit, and Plasticity Index of Soils. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM D2216; Standard Test Methods for Laboratory Determination of Water (Moisture) Content of Soil and Rock By Mass. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Scalia, J., IV; Benson, C.H.; Bohnhoff, G.L.; Edil, T.B.; Shackelford, C.D. Long-term hydraulic conductivity of a bentonite-polymer composite permeated with aggressive inorganic solutions. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 2014, 140, 04013025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van’t Woudt, B.D. Particle coatings affecting the wettability of soils. J. Geophys. Res. 1959, 64, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, L.W.; Doerr, S.H.; Oostindie, K.; Ziogas, A.K.; Ritsema, C.J. Water repellency and critical soil water content in a dune sand. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2001, 65, 1667–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M.; Guerra, J.C.; Vahedifard, F.; Robichaud, P.R.; Akin, I.D. Temporal changes in soil water retention in burned and unburned areas after a wildfire and implications for slope stability. Can. Geotech. J. 2025, 62, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, P.M. Comparison of methods for measuring severity of water repellence of sandy soils and assessment of some factors that affect its measurement. Aust. J. Soil Res. 1981, 19, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenu, C.; Le Bissonnais, Y.; Arrouays, D. Organic matter influence on clay wettability and soil aggregate stability. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2000, 64, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7503; Standard Test Method for Measuring the Exchange Complex and Cation Exchange Capacity of Inorganic Fine-Grained Soils. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- Akin, I.D.; Likos, W.J. Single-point and multi-point water-sorption methods for specific surface areas of clay. Geotech. Test. J. 2016, 39, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2487; Standard Practice for Classification of Soils for Engineering Purposes (Unified Soil Classification System). ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Cerrato, J.M.; Blake, J.M.; Hirani, C.; Clark, A.L.; Ali, A.M.S.; Artyushkova, K.; Peterson, E.; Bixby, R.J. Wildfires and water chemistry: Effect of metals associated with wood ash. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2016, 18, 1078–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Úbeda, X.; Pereira, P.; Outeiro, L.; Martin, D.A. Effects of fire temperature on the physical and chemical characteristics of the ash from two plots of Cork oak (Quercus Suber). Land Degrad. Dev. 2009, 20, 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfour, V.N.; Woods, S.W. The hydrological properties and the effects of hydration on vegetative ash from the Northern Rockies, USA. Catena 2013, 111, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Cui, Y.; Ni, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, D.; Yi, S.; Jin, W.; Zhou, L. Temporal evolution of the hydromechanical properties of soil-root systems in a forest fire in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 809, 151165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, H.W.; Biswas, A.; Vujanovic, V.; Si, B.C. Relationship between the severity, persistence of soil water repellency and the critical soil water content in water repellent soils. Geoderma 2014, 221, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayad, M.; Chau, H.W.; Trolove, S.; Moir, J.; Condron, L.; Bouray, M. The relationship between soil moisture and soil water repellency persistence in hydrophobic soils. Water 2020, 12, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, M.; Frankenberger, W.T., Jr.; Stolzy, L.H. The influence of organic matter on soil aggregation and water infiltration. J. Prod. Agric. 1989, 2, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felton, G.K.; Ali, M. Hydraulic parameter response to incorporated organic matter in the B-horizon. Trans. ASAE 1992, 35, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lado, M.; Paz, A.; Ben-Hur, M. Organic matter and aggregate size interactions in infiltration, seal formation, and soil loss. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2004, 68, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, I.N.; Heinse, R.; Smith, A.M.S.; McDaniel, P.A. Root decay and fire affect soil pipe formation and morphology in forested hillslopes with restrictive horizons. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2014, 78, 1448–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cation Exchange Capacity, CEC ^ (cmol+/kg) | Specific Surface Area, SSA (m2/g) | Organic Content *, Immediately After (%) | Organic Content, One Year After (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Ash | 8.7 ± 0.72 | 8.2 | 4.5 ± 0.08 | --- |

| Subsurface Ash | 6.8 ± 0 | 2.5 | 1.1 ± 0.03 | 2.2 ± 0.06 |

| Water-Repellent Soil | 8.1 ± 0.36 | 1.6 | 2.5 ± 0.13 | 2.3 ± 0.12 |

| Soil | 15.2 ± 0.45 | 22.3 | 5.8 ± 0.30 | 9.2 ± 0.29 |

| WDPT Test Classification | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Actual Water Repellency | Potential Water Repellency | ||

| Immediately after the fire | Surface Ash | Nonrepellent | Nonrepellent |

| Subsurface Ash | Nonrepellent | Nonrepellent | |

| Water-Repellent Soil | Extremely Repellent | Extremely Repellent | |

| Soil | Slightly Repellent | Nonrepellent | |

| One year after the fire | Subsurface Ash | Nonrepellent | Nonrepellent |

| Water-Repellent Soil | Extremely Repellent | Extremely Repellent | |

| Soil | Nonrepellent | Nonrepellent | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Demir, M.; Robichaud, P.R.; Akin, I.D. Persistence of Soil Water Repellency After the 2022 Bolt Creek Fire. Geosciences 2025, 15, 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120472

Demir M, Robichaud PR, Akin ID. Persistence of Soil Water Repellency After the 2022 Bolt Creek Fire. Geosciences. 2025; 15(12):472. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120472

Chicago/Turabian StyleDemir, Mustafa, Peter R. Robichaud, and Idil Deniz Akin. 2025. "Persistence of Soil Water Repellency After the 2022 Bolt Creek Fire" Geosciences 15, no. 12: 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120472

APA StyleDemir, M., Robichaud, P. R., & Akin, I. D. (2025). Persistence of Soil Water Repellency After the 2022 Bolt Creek Fire. Geosciences, 15(12), 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120472