Effects of Rumen-Protected β-Alanine on Growth Performance, Rumen Microbiome, and Serum Metabolome of Beef Cattle

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Treatment and Experimental Diets

2.2. Growth Performance Measurement and Sample Collection

2.3. Chemical Analyses

2.4. 16S rDNA Sequencing Analysis

2.5. Metabolomics Analysis by Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry

2.6. Associations Between Species and Pathways

2.7. Statistics and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance and Apparent Digestibility of Nutrients

3.2. Serum Indices

3.3. Rumen Fermentation Indicators

3.4. Rumen Bacterial Diversity

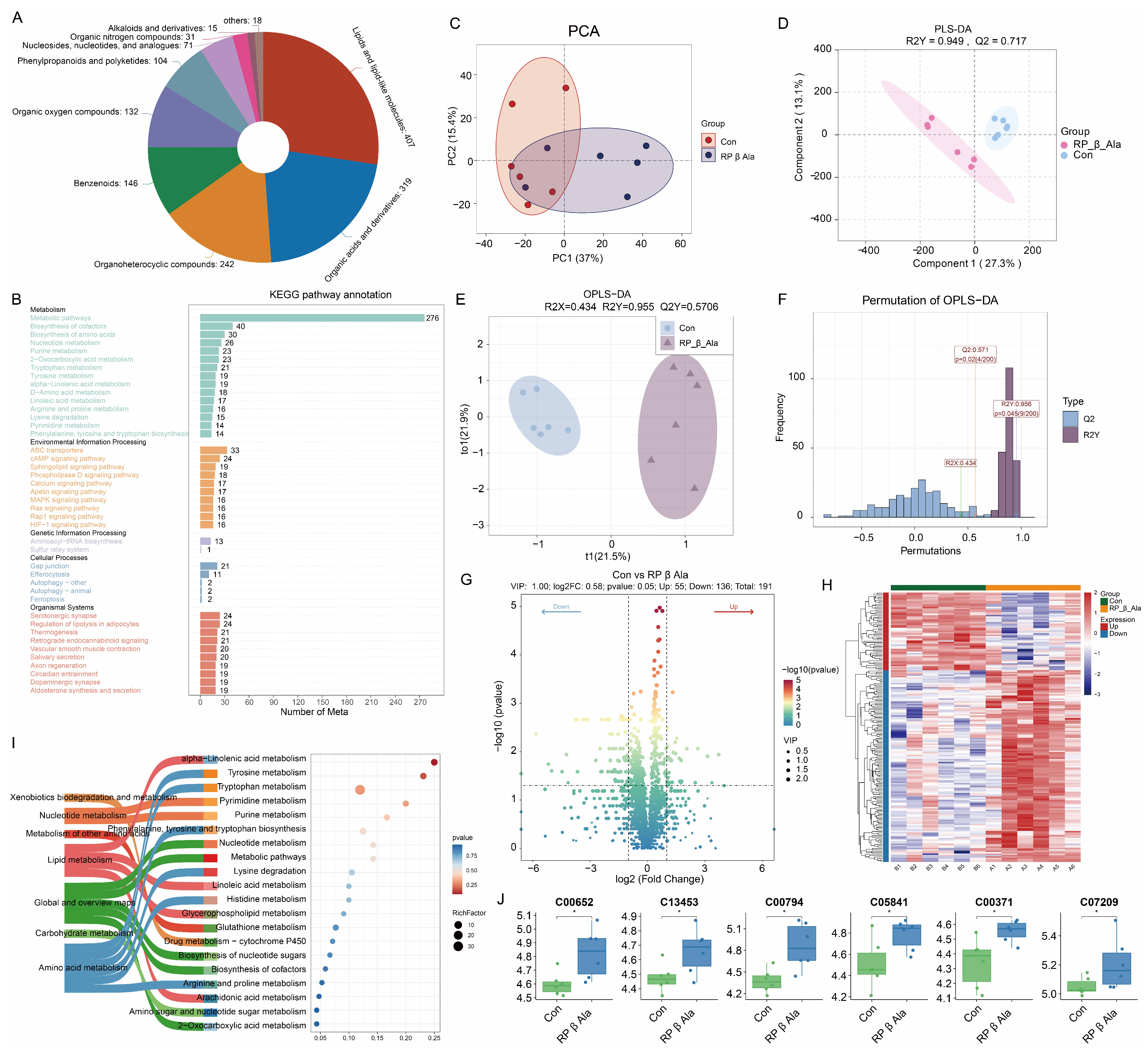

3.5. Rumen Fluid Metabolomics

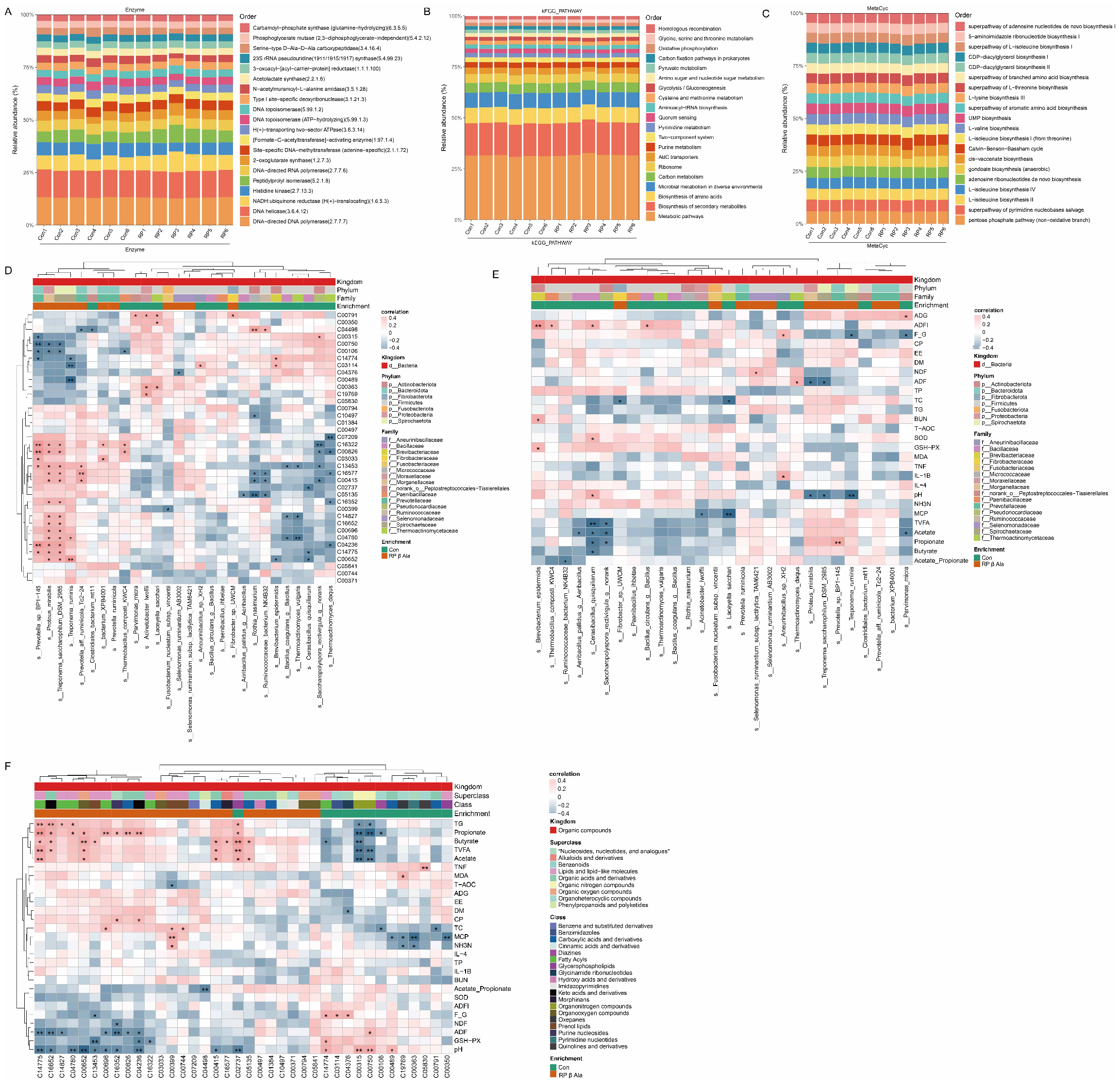

3.6. Microbial Function Prediction Analysis and Correlation Analysis

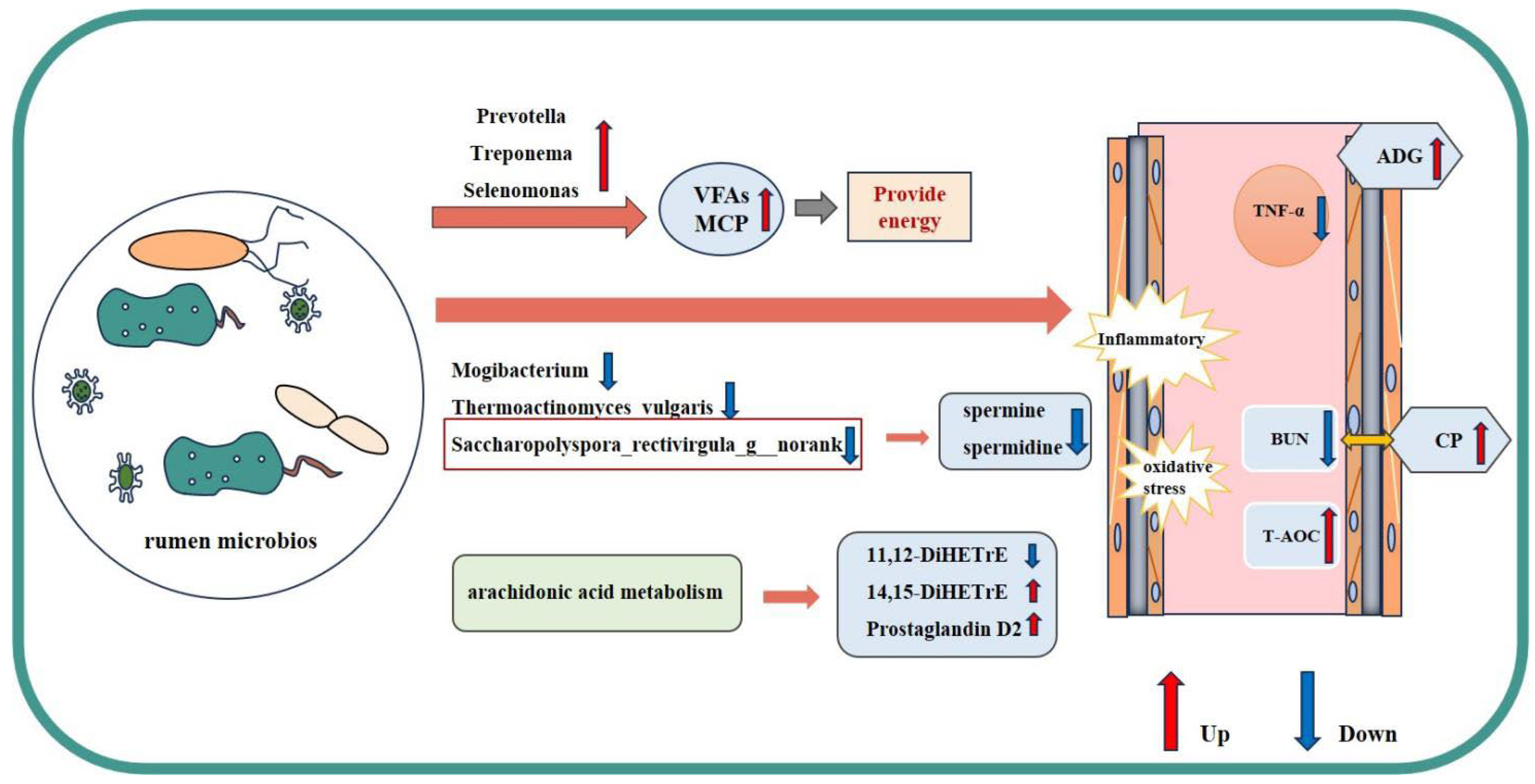

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Supplementary Rumen-Protected β-Ala on Growth Performance and Feed Conversion in Beef Cattle

4.2. Effect of Supplementary Rumen-Protected β-Ala on Serum Biochemical Parameters in Beef Cattle

4.3. Effect of Supplementary Rumen-Protected β-Ala on Rumen Fermentation and Bacteria in Beef Cattle

4.4. Effect of Supplementary Rumen-Protected β-Ala on Rumen Metabolomics in Beef Cattle

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J.; Shen, C.; Zhao, G.; Hanigan, M.D.; Li, M. Dietary protein re-alimentation following restriction improves protein deposition via changing amino acid metabolism and transcriptional profiling of muscle tissue in growing beef bulls. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 19, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Khan, M.; Mushtaq, M.; Ni, X.; Danzeng, B.; Yang, H.; Ali, S.; Farid, S.K.; Quan, G. Influence of dietary protein levels on metabolism of nitrogen, phosphorus, and calcium in a chinese indigenous sheep (ovis aries). Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2025, 57, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, R.; Yu, Y.; Suo, Y.; Fu, B.; Gao, H.; Han, L.; Leng, J. Effects of feeding reduced protein diets on milk quality, nitrogen balance and rumen microbiota in lactating goats. Animals 2025, 15, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Bossche, T.; Goossens, K.; Ampe, B.; Haesaert, G.; De Sutter, J.; De Boever, J.L.; Vandaele, L. Effect of supplementing rumen-protected methionine, lysine, and histidine to low-protein diets on the performance and nitrogen balance of dairy cows. J. Dairy. Sci. 2023, 106, 1790–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, P.; Degen, A.A.; He, K.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, A.; Zhou, J. Effect of rumen-protected lysine supplementation on growth performance, blood metabolites, rumen fermentation and bacterial community on feedlot yaks offered corn-based diets. Animals 2025, 15, 2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyat, M.S.; Al-Sagheer, A.; Noreldin, A.E.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Khafaga, A.F.; Abdel-Latif, M.A.; Swelum, A.A.; Arif, M.; Salem, A.Z.M. Beneficial effects of rumen-protected methionine on nitrogen-use efficiency, histological parameters, productivity and reproductive performance of ruminants. Anim. Biotechnol. 2021, 32, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, P.; Pang, S.; Ma, M.; Nie, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W. Rumen-protected leucine improved growth performance of fattening sheep by changing rumen fermentation patterns. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Xu, W.; Wei, F. Advances in the synthesis of β-alanine. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1283129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, S.W.; Chen, W.L.; Chien, K.Y.; Hsu, C.W. Dosing strategies for β-alanine supplementation in strength and power performance: A systematic review. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2025, 22, 2566368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, B.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Wu, S.; Qi, G.; Zhang, H. Effect of dietary beta-alanine supplementation on growth performance, meat quality, carnosine content, and gene expression of carnosine-related enzymes in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 1220–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xie, J.; Fu, C.; Guo, H.; Chen, J.; Yin, Y. Effects of dietary beta-alanine supplementation on growth performance, meat quality, carnosine content, amino acid composition and muscular antioxidant capacity in chinese indigenous ningxiang pig. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 107, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, B.; Wang, J.; Hu, M.; Ma, Y.; Wu, S.; Qi, G.; Qiu, K.; Zhang, H. Influences of beta-alanine and l-histidine supplementation on growth performance, meat quality, carnosine content, and mRNA expression of carnosine-related enzymes in broilers. Animals 2021, 11, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lackner, J.; Albrecht, A.; Mittler, M.; Marx, A.; Kreyenschmidt, J.; Hess, V.; Sauerwein, H. Effect of feeding histidine and β-alanine on carnosine concentration, growth performance, and meat quality of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, D.H.; Ko, Y.S.; Prabowo, C.P.S.; Lee, S.Y. Microbial production of propionic acid through a novel β-alanine route. Metab. Eng. 2026, 93, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trexler, E.T.; Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Stout, J.R.; Hoffman, J.R.; Wilborn, C.D.; Sale, C.; Kreider, R.B.; Jager, R.; Earnest, C.P.; Bannock, L.; et al. International society of sports nutrition position stand: Beta-alanine. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2015, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Liu, C.; Li, M.; Zhao, G. Beta-alanine decreases plasma taurine but improves nitrogen utilization efficiency in beef steers. Anim. Nutr. 2025, 22, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Zhao, G. Impact of dietary supplementation with beta-alanine on the rumen microbial crude protein supply, nutrient digestibility and nitrogen retention in beef steers elucidated through sequencing the rumen bacterial community. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 17, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jiang, H.; Hao, L.; Cao, X.; Degen, A.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, C. Rumen bacterial community of grazing lactating yaks (poephagus grunniens) supplemented with concentrate feed and/or rumen-protected lysine and methionine. Animals 2021, 11, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachirapakorn, C.; Pilachai, K.; Wanapat, M.; Pakdee, P.; Cherdthong, A. Effect of ground corn cobs as a fiber source in total mixed ration on feed intake, milk yield and milk composition in tropical lactating crossbred holstein cows. Anim. Nutr. 2016, 2, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy. Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemist. Official Methods of Analysis; AOAC: Arlington, VA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Mao, K.; Zang, Y.; Lu, G.; Qiu, Q.; Ouyang, K.; Zhao, X.; Song, X.; Xu, L.; Liang, H.; et al. Revealing the developmental characterization of rumen microbiome and its host in newly received cattle during receiving period contributes to formulating precise nutritional strategies. Microbiome 2023, 11, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, K.; Lu, G.; Li, Y.; Zang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Qiu, Q.; Qu, M.; Ouyang, K. Effects of rumen-protected creatine pyruvate on blood biochemical parameters and rumen fluid characteristics in transported beef cattle. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, L.; Qiu, Q.; Ouyang, K.; Qu, M. Dietary supplementation with creatine pyruvate alters rumen microbiota protein function in heat-stressed beef cattle. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 715088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoc, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Garrity, G.M.; Tiedje, J.M.; Cole, J.R. Naive bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5261–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A. Ggpubr: “Ggplot2” Based Publication Ready Plots, R Package Version 0.6.2. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggpubr/index.html (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Kolde, R. Pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps, R Package Version 1.0.13. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/index.html (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Zhu, W.; Xu, W.; Wei, C.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, C.; Chen, X. Effects of decreasing dietary crude protein level on growth performance, nutrient digestion, serum metabolites, and nitrogen utilization in growing goat kids (Capra hircus). Animals 2020, 10, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, C.P.; Mainau, E.; Ceron, J.J.; Contreras-Aguilar, M.D.; Martinez-Subiela, S.; Navarro, E.; Tecles, F.; Manteca, X.; Escribano, D. Biomarkers of oxidative stress in saliva in pigs: Analytical validation and changes in lactation. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alugongo, G.M.; Xiao, J.X.; Chung, Y.H.; Dong, S.Z.; Li, S.L.; Yoon, I.; Wu, Z.H.; Cao, Z.J. Effects of saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation products on dairy calves: Performance and health. J. Dairy. Sci. 2017, 100, 1189–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belviranli, M.; Okudan, N.; Revan, S.; Balci, S.; Gokbel, H. Repeated supramaximal exercise-induced oxidative stress: Effect of beta-alanine plus creatine supplementation. Asian J. Sports Med. 2016, 7, e26843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, G.; Di Pietro, L.; Cardaci, V.; Maugeri, S.; Caraci, F. The therapeutic potential of carnosine: Focus on cellular and molecular mechanisms. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov. 2023, 4, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, C.; Niu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, F.; Li, F. An intensive milk replacer feeding program benefits immune response and intestinal microbiota of lambs during weaning. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.; Webb, M.; Ghimire, S.; Blair, A.; Olson, K.; Fenske, G.J.; Fonder, A.T.; Christopher-Hennings, J.; Brake, D.; Scaria, J. Metagenomic characterization of the effect of feed additives on the gut microbiome and antibiotic resistome of feedlot cattle. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coma, J.; Carrion, D.; Zimmerman, D.R. Use of plasma urea nitrogen as a rapid response criterion to determine the lysine requirement of pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Zeng, S.; Zhang, R.; Diao, Q.; Tu, Y. Effects of dietary energy levels on rumen bacterial community composition in holstein heifers under the same forage to concentrate ratio condition. BMC Microbiol. 2018, 18, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharechahi, J.; Vahidi, M.F.; Bahram, M.; Han, J.; Ding, X.; Salekdeh, G.H. Metagenomic analysis reveals a dynamic microbiome with diversified adaptive functions to utilize high lignocellulosic forages in the cattle rumen. ISME J. 2021, 15, 1108–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lv, J.; Hui, J.; Wu, A.; Zhao, L.; Feng, L.; Deng, L.; Yu, M.; Liu, F.; Yao, J.; et al. Dietary saccharin sodium supplementation improves the production performance of dairy goats without residue in milk in summer. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 18, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, K.M.; Beauchemin, K.A. Nitrogen metabolism and route of excretion in beef feedlot cattle fed barley-based backgrounding diets varying in protein concentration and rumen degradability. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 2295–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, A.Z.; Koike, S.; Kobayashi, Y. Phylogenetic diversity and dietary association of rumen treponema revealed using group-specific 16s rRNA gene-based analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2011, 316, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Penner, G.B.; Li, M.; Oba, M.; Guan, L.L. Changes in bacterial diversity associated with epithelial tissue in the beef cow rumen during the transition to a high-grain diet. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 5770–5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, M.; Xie, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Ma, X.; Sun, H.; Liu, J. Integrated meta-omics reveals new ruminal microbial features associated with feed efficiency in dairy cattle. Microbiome 2022, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, R.J.; Rooke, J.A.; McKain, N.; Duthie, C.; Hyslop, J.J.; Ross, D.W.; Waterhouse, A.; Watson, M.; Roehe, R. The rumen microbial metagenome associated with high methane production in cattle. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bian, G.; Zhu, W.; Mao, S. High-grain feeding causes strong shifts in ruminal epithelial bacterial community and expression of toll-like receptor genes in goats. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershwin, L.J.; Himes, S.R.; Dungworth, D.L.; Giri, S.N.; Friebertshauser, K.E.; Camacho, M. Effect of bovine respiratory syncytial virus infection on hypersensitivity to inhaled micropolyspora faeni. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1994, 104, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, E.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Montiel, M.; Zoltan, M.; Dong, W.; Quesada, P.; Sahin, I.; Chandra, V.; San Lucas, A.; et al. Tumor microbiome diversity and composition influence pancreatic cancer outcomes. Cell 2019, 178, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcik, W.; Swider, O.; Lukasiewicz-Mierzejewska, M.; Damaziak, K.; Riedel, J.; Marzec, A.; Wojcicki, M.; Roszko, M.; Niemiec, J. Content of amino acids and biogenic amines in stored meat as a result of a broiler diet supplemented with beta-alanine and garlic extract. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Jimenez, F.; Medina, M.A.; Villalobos-Rueda, L.; Urdiales, J.L. Polyamines in mammalian pathophysiology. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 3987–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamana, K.; Matsuzaki, S. Polyamines as a chemotaxonomic marker in bacterial systematics. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 1992, 18, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wu, L.; Chen, J.; Dong, L.; Chen, C.; Wen, Z.; Hu, J.; Fleming, I.; Wang, D.W. Metabolism pathways of arachidonic acids: Mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, J.N.; Roshandelpoor, A.; Alotaibi, M.; Choudhary, A.; Jain, M.; Cheng, S.; Zarbafian, S.; Lau, E.S.; Lewis, G.D.; Ho, J.E. The association of eicosanoids and eicosanoid-related metabolites with pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 62, 2300561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, R.; Quehenberger, O.; Armando, A.; Dennis, E.A. Polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolites as novel lipidomic biomarkers for noninvasive diagnosis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, X.; Yao, M.; Sun, B.; Zhu, K.; Wang, W.; Zhang, A. LC-MS based untargeted metabolomics studies of the metabolic response of ginkgo biloba extract on arsenism patients. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 274, 116183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, T. Discovery of anti-inflammatory role of prostaglandin d(2). Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi 2015, 146, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredients | Content | Nutrients | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brewer’s grains | 29.74 | Dry matter | 63.97 |

| Rice straw silage | 25.95 | Crude protein | 14.35 |

| Corn | 21.84 | Crude fat | 4.68 |

| Soybean meal | 6.38 | Ash | 8.39 |

| Whet Straw | 5.74 | Neutral detergent fiber | 32.65 |

| Wheat bran | 2.95 | Acid detergent fiber | 13.23 |

| Microbial agent | 4.73 | ||

| NaHCO3 | 0.7 | ||

| Premix 1 | 1.97 | ||

| Total | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fu, D.; Mao, K.; Zang, Y.; Qu, M.; Qiu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Ouyang, K.; Li, Y. Effects of Rumen-Protected β-Alanine on Growth Performance, Rumen Microbiome, and Serum Metabolome of Beef Cattle. Animals 2026, 16, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010043

Fu D, Mao K, Zang Y, Qu M, Qiu Q, Zhao X, Ouyang K, Li Y. Effects of Rumen-Protected β-Alanine on Growth Performance, Rumen Microbiome, and Serum Metabolome of Beef Cattle. Animals. 2026; 16(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Daci, Kang Mao, Yihao Zang, Mingren Qu, Qinghua Qiu, Xianghui Zhao, Kehui Ouyang, and Yanjiao Li. 2026. "Effects of Rumen-Protected β-Alanine on Growth Performance, Rumen Microbiome, and Serum Metabolome of Beef Cattle" Animals 16, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010043

APA StyleFu, D., Mao, K., Zang, Y., Qu, M., Qiu, Q., Zhao, X., Ouyang, K., & Li, Y. (2026). Effects of Rumen-Protected β-Alanine on Growth Performance, Rumen Microbiome, and Serum Metabolome of Beef Cattle. Animals, 16(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010043