Digestive Enzyme Activity and Temperature: Evolutionary Constraint or Physiological Flexibility?

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

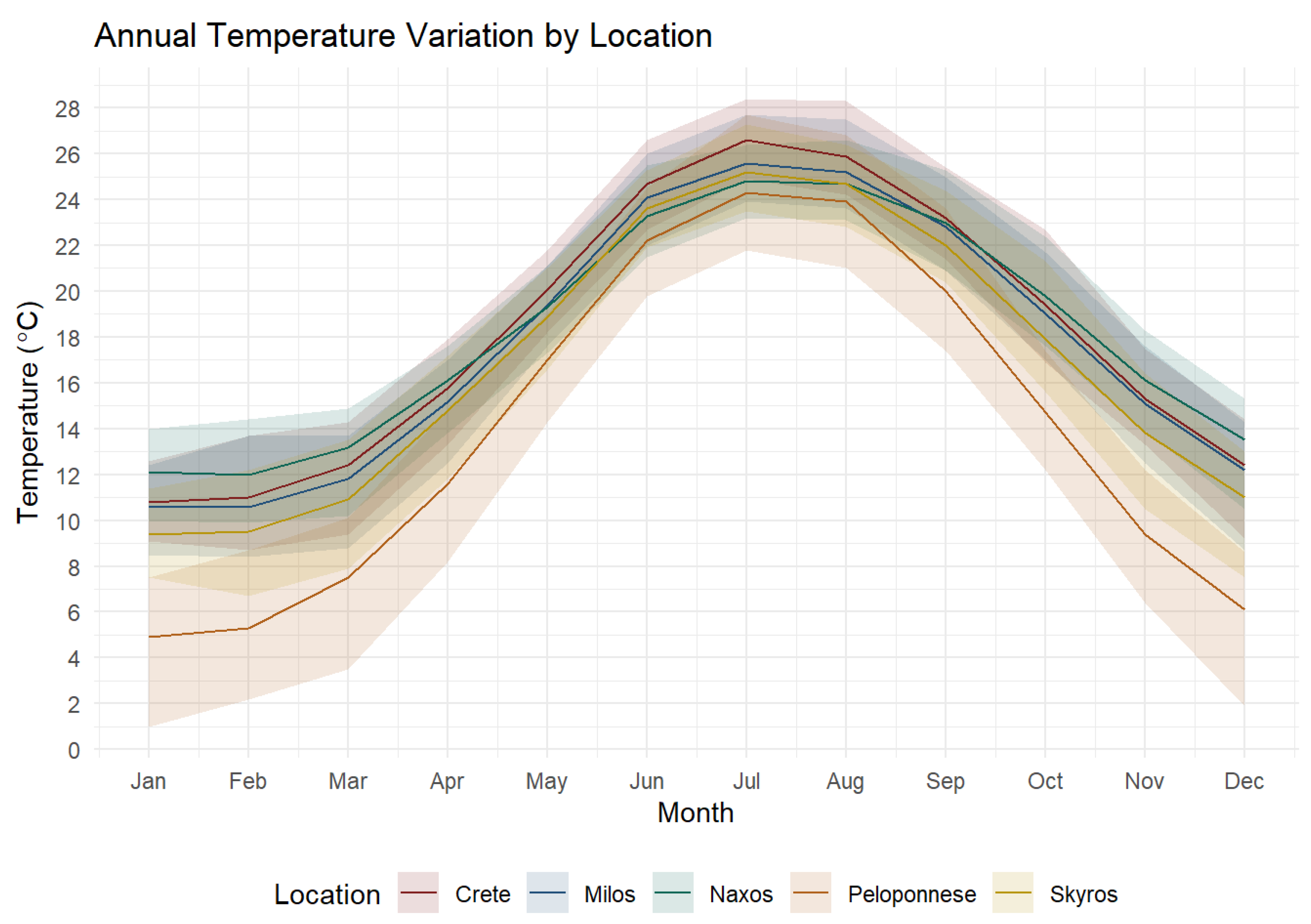

2.1. Study Species and Area

2.2. Intestinal Tissue Preparation

2.3. Assays of Digestive Enzyme Activities

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Phylogenetic Signal

3. Results

3.1. Body Size and Gut Length

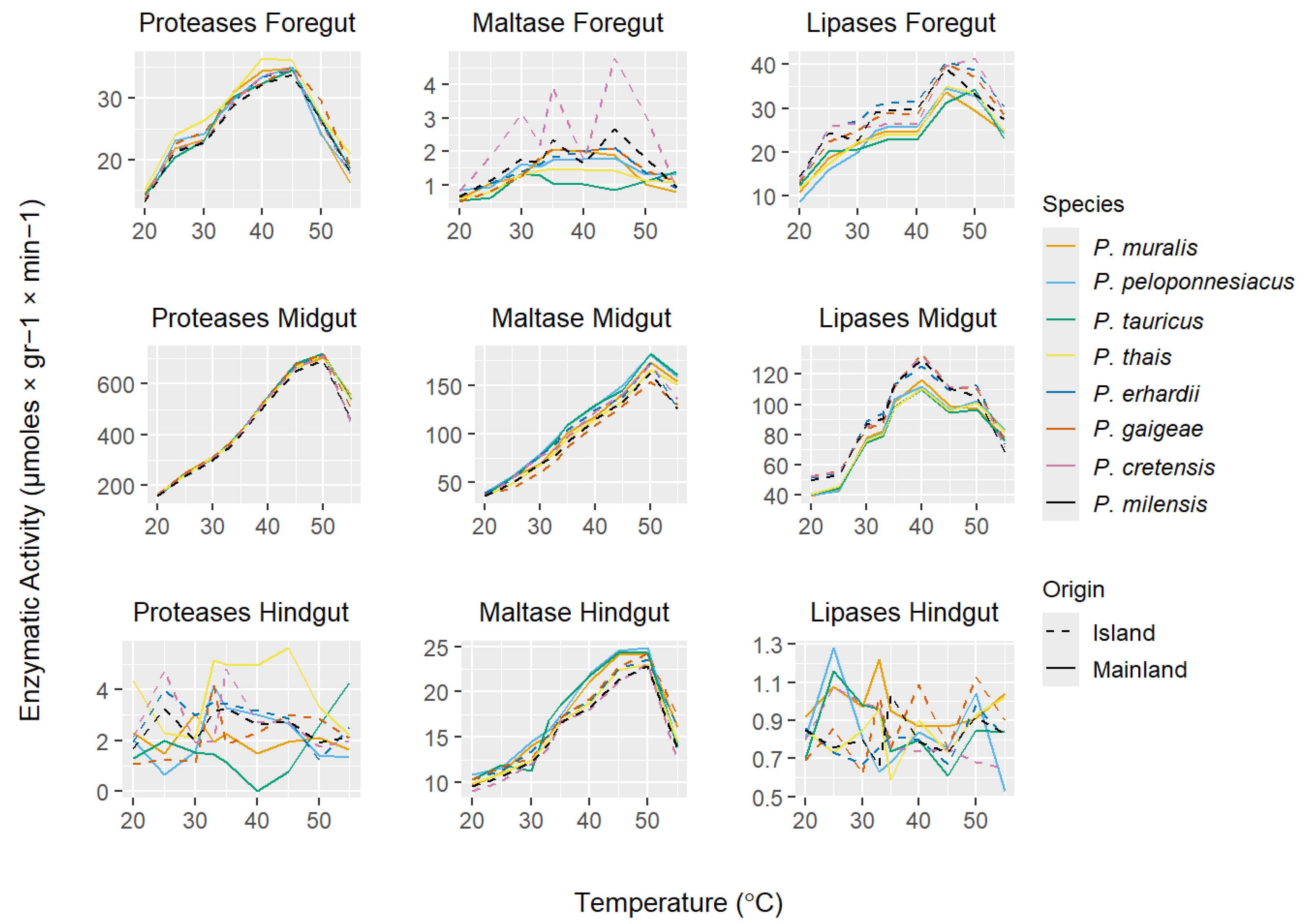

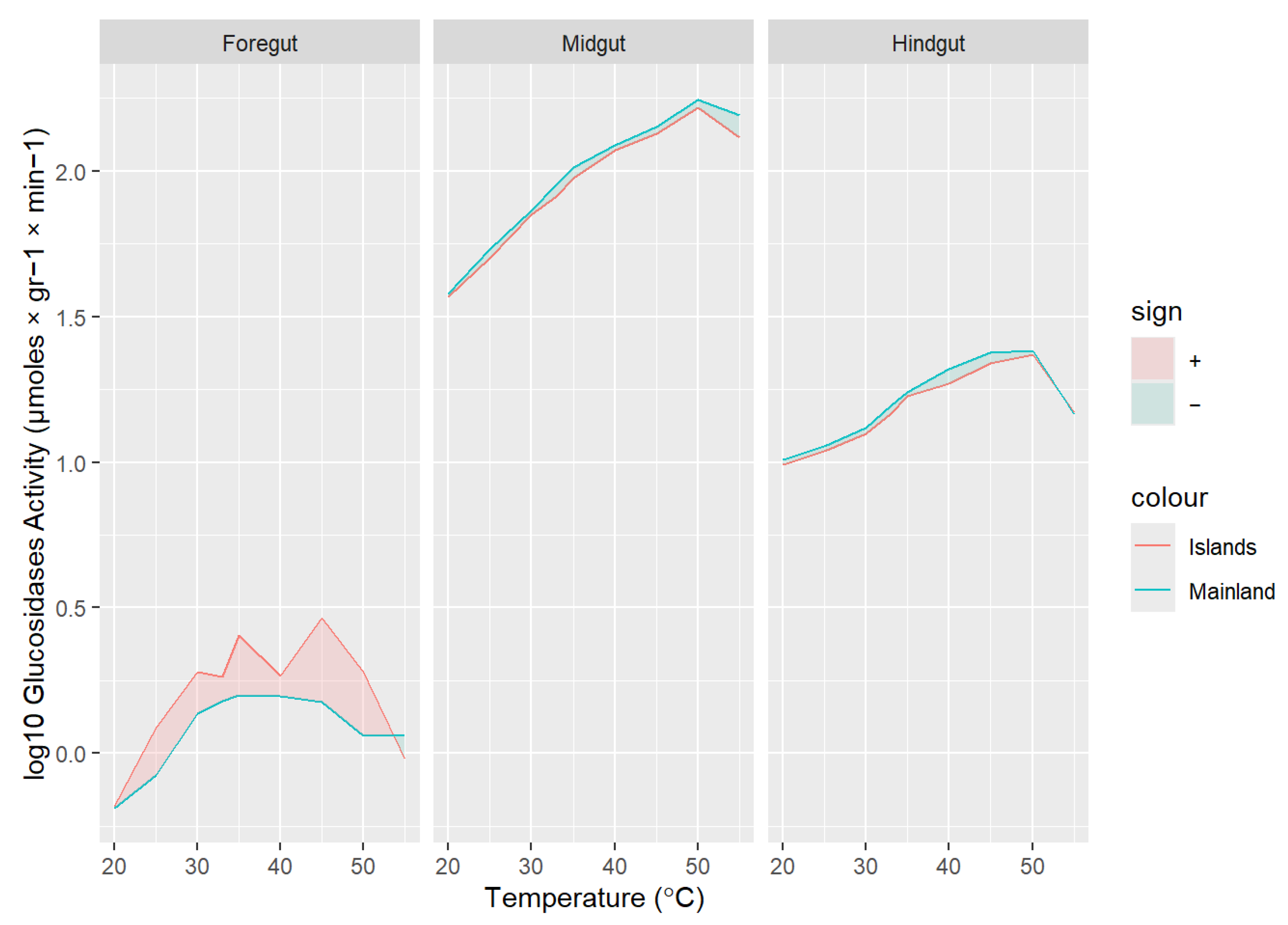

3.2. Digestive Enzyme Activities

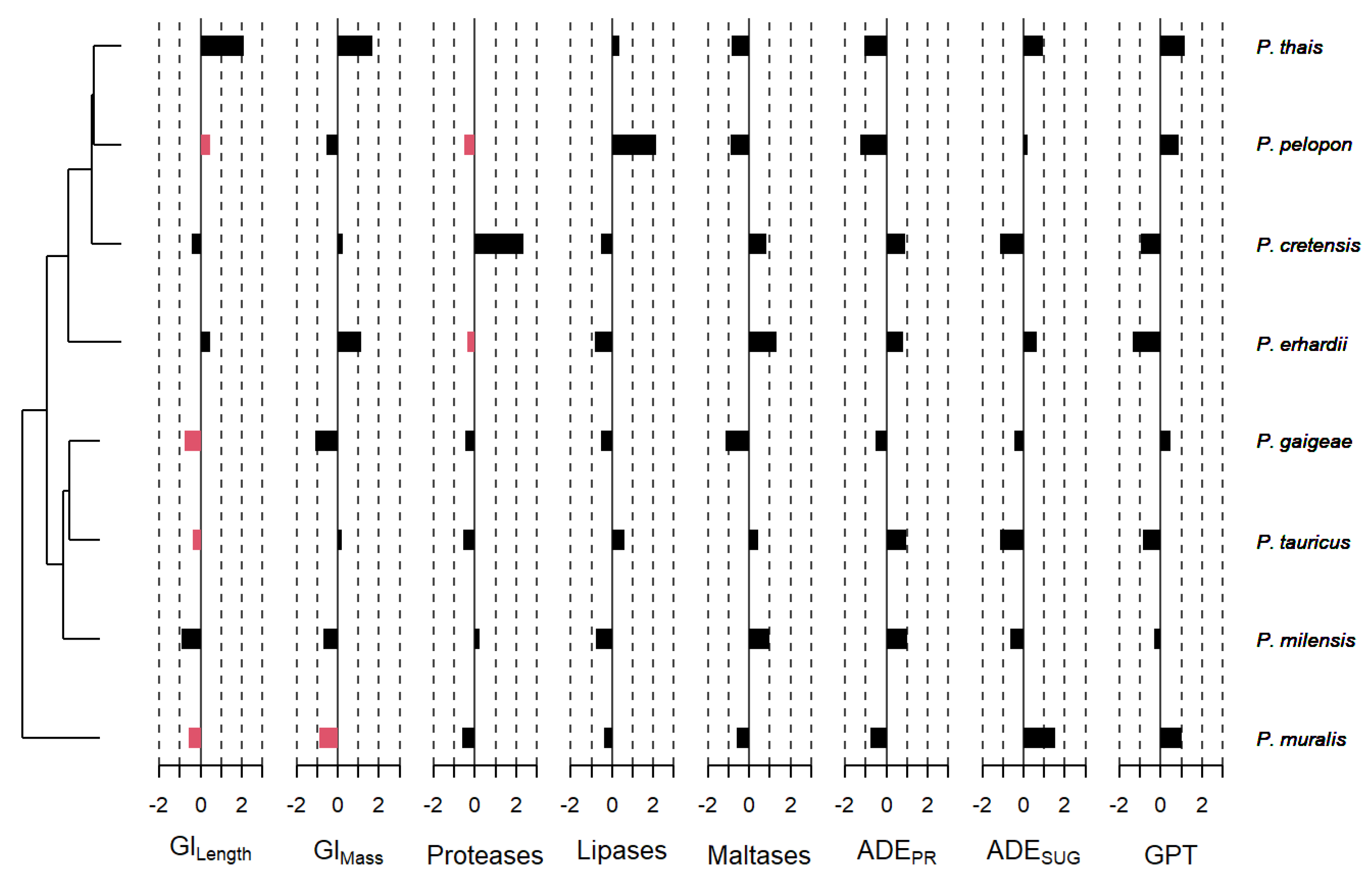

3.3. Phylogenetic Signal Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pfenning-Butterworth, A.; Buckley, L.B.; Drake, J.M.; Farner, J.E.; Farrell, M.J.; Gehman, A.-L.M.; Mordecai, E.A.; Stephens, P.R.; Gittleman, J.L.; Davies, T.J. Interconnecting global threats: Climate change, biodiversity loss, and infectious diseases. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e270–e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silveira, R.M.F.; Façanha, D.A.E.; de Vasconcelos, A.M.; Leite, S.C.B.; Leite, J.H.G.M.; Saraiva, E.P.; Fávero, L.P.; Tedeschi, L.O.; da Silva, I.J.O. Physiological adaptability of livestock to climate change: A global model-based assessment for the 21st century. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2026, 116, 108061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunday, J.M.; Bates, A.E.; Dulvy, N.K. Thermal tolerance and the global redistribution of animals. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pafilis, P.; Foufopoulos, J.; Poulakakis, N.; Lymberakis, P.; Valakos, E. Digestive performance in five Mediterranean lizard species: Effects of temperature and insularity. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2007, 177, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinon, W.; Alexander, G.J. Is temperature independence of digestive efficiency an experimental artefact in lizards? A test using the common flat lizard (Platysuarus intermedius). Copeia 1999, 1999, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angilletta, M.J.J. Thermal Adaptation: A Theoritical and Empirical Synthesis; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, M.; Knutti, R.; Arblaster, J.; Dufresne, J.-L.; Fichefet, T.; Friedlingstein, P.; Gao, X.; Gutowski, W.J.; Johns, T.; Krinner, G.; et al. Long-term Climate Change: Projections, Commitments and Irreversibility. In Climate Change 2013—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Porta, J.; Šmíd, J.; Sol, D.; Fasola, M.; Carranza, S. Testing the island effect on phenotypic diversification: Insights from the Hemidactylus geckos of the Socotra Archipelago. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-P.; Chiou, C.-R.; Lin, T.-E.; Tu, M.-C.; Lin, C.-C.; Porter, W.P. Future advantages in energetics, activity time, and habitats predicted in a high-altitude pit viper with climate warming. Funct. Ecol. 2013, 27, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, H.H.; Opdal, A.F.; Enberg, K. Life-history evolution in response to foraging risk, modelled for Northeast Arctic cod (Gadus morhua). Ecol. Model. 2023, 482, 110378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, J.C.; Thavamani, A. Physiology, Gastrocolic Reflex. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sagonas, K.; Pafilis, P.; Valakos, E.D. Effects of insularity on digestive performance: Living in islands induces shifts in physiological and morphological traits in a Mediterranean lizard? Sci. Nat. 2015, 102, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasov, W.H.; Martinez Del Rio, C. Physiological Ecology: How Animals Process Energy, Nutrients, and Toxins; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo, L.F.; Abe, A.S.; Andrade, D.V. Temperature and meal size effects on the postprandial metabolism and energetics in a boid snake. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2003, 76, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Zaar, M.; Arvedsen, S.; Vedel-Smith, C.; Overgaard, J. Effects of temperature on the metabolic response to feeding in Python molurus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2002, 133, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, E.R. The physiology of lipid storage and use in reptiles. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2017, 92, 1406–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, C.-E.; Bhagavan, N.V. Essentials of Medical Biochemistry with Clinical Cases, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.T.; Comay, O.; Maul, L.; Wegmüller, F.; Le Tensorer, J.-M.; Dayan, T. A model of digestive tooth corrosion in lizards: Experimental tests and taphonomic implications. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagonas, K.; Deimezis-Tsikoutas, A.; Reppa, A.; Domenikou, I.; Papafoti, M.; Synevrioti, K.; Polydouri, I.; Voutsela, A.; Bletsa, A.; Karambotsi, N.; et al. Tail regeneration alters the digestive performance of lizards. J. Evol. Biol. 2021, 34, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofer, R. The adaptation of digestive enzymes to temperature, season and diet in roach, Rutilus rutilus and rudd Scardinius erythrophthalmus; Proteases. J. Fish Biol. 1979, 15, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, D.P.; Bittong, R.A. Digestive enzyme activities and gastrointestinal fermentation in wood-eating catfishes. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2009, 179, 1025–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, R.; Schiemer, F. Proteolytic activity in the digestive tract of several species of fish with different feeding habits. Oecologia 1981, 48, 342–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez del Rio, C. Sugar preferences in hummingbirds: The influence of subtle chemical differences on food choice. Codor 1990, 92, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Kohl, K.D.; Ciminari, M.E.; Chediack, J.G.; Leafloor, J.O.; Karasov, W.H.; McWilliams, S.R.; Caviedes-Vidal, E. Modulation of digestive enzyme activities in the avian digestive tract in relation to diet composition and quality. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2017, 187, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacace, J.; Marinone, G.F.; Cid, F.D.; Chediack, J.G. Impacts of heat stress and its mitigation by capsaicin in health status and digestive enzymes in house sparrows (Passer domesticus). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2025, 308, 111909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaneli, V.; Valakos, E.D.; Pafilis, P.; Lymberakis, P. Thermoregulation by the lizard Podarcis cretensis (Squamata; Lacertidae) in Western Crete: Variation between three populations along an altitudinal gradient. In Proceedings of the 6th Symposium on the Lacertids of the Mediterranean Basin, Lesvos, Greece, 23–27 June 2008; p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Pafilis, P.; Herrel, A.; Kapsalas, G.; Vasilopoulou-Kampitsi, M.; Fabre, A.-C.; Foufopoulos, J.; Donihue, C.M. Habitat shapes the thermoregulation of Mediterranean lizards introduced to replicate experimental islets. J. Therm. Biol. 2019, 84, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reppa, A.; Agori, A.F.; Santikou, P.; Parmakelis, A.; Pafilis, P.; Valakos, E.D.; Sagonas, K. Small Island Effects on the Thermal Biology of the Endemic Mediterranean Lizard Podarcis gaigeae. Animals 2023, 13, 2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagonas, K.; Kapsalas, G.; Valakos, E.; Pafilis, P. Living in sympatry: The effect of habitat partitioning on the thermoregulation of three Mediterranean lizards. J. Therm. Biol. 2017, 65, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulakakis, N.; Lymberakis, P.; Valakos, E.; Zouros, E.; Mylonas, M. Phylogenetic relationships and biogeography of Podarcis species from the Balkan Peninsula, by Bayesian and maximum likelihood analyses of mitochondrial DNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2005, 37, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilani, L.; Bougiouri, K.; Antoniou, A.; Psonis, N.; Poursanidis, D.; Lymberakis, P.; Poulakakis, N. Multigene phylogeny, phylogeography and population structure of Podarcis cretensis species group in south Balkans. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2019, 138, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiourtsoglou, A.; Kaliontzopoulou, A.; Poursanidis, D.; Jablonski, D.; Lymberakis, P.; Poulakakis, N. Evidence of cryptic diversity in Podarcis peloponnesiacus and re-evaluation of its current taxonomy; insights from genetic, morphological, and ecological data. J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 2021, 59, 2350–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulou, C.; Valakos, E.; Pafilis, P. Summer diet of Podarcis milensis, Podarcis gaigeae and Podarcis erhardii (Sauria: Lacertidae). Bonn. Zool. Bull. 1999, 48, 275–282. [Google Scholar]

- Kotini-Zabaka, S. Contribution to the Study of the Climate of Greece. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Schwaner, T.D. A field study of thermoregulation in black tiger snakes (Notechis ater niger: Elapidae) on the Franklin Islands, South Australia. Herpetologica 1989, 45, 393–401. [Google Scholar]

- Liwanag, H.E.M.; Haro, D.; Callejas, B.; Labib, G.; Pauly, G.B. Thermal tolerance varies with age and sex for the nonnative Italian Wall Lizard (Podarcis siculus) in Southern California. J. Therm. Biol. 2018, 78, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litmer, A.R.; Murray, C.M. Critical thermal tolerance of invasion: Comparative niche breadth of two invasive lizards. J. Therm. Biol. 2019, 86, 102432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.F.; Ju, L.-K. On optimization of enzymatic processes: Temperature effects on activity and long-term deactivation kinetics. Process Biochem. 2023, 130, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, X.; Li, X.; Zhu, T.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, X.; Yang, D. Effects of water temperature on growth performance, digestive enzymes activities, and serum indices of juvenile Coreius guichenoti. J. Therm. Biol. 2023, 115, 103595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, G.; Lederer, H. Fluorometric measurement of triglycerides. In Automation in Analytical Chemistry, Technicon Symposia; Skeggs, L.T.J., Ed.; Mediad Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1965; pp. 341–344. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Blomberg, S.P.; Garland, T.; Ives, A.R.; Crespi, B. Testing for phylogenetic signal in comparative data: Behavioral traits are more labile. Evolution 2003, 57, 717–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagel, M. Inferring the historical patterns of biological evolution. Nature 1999, 401, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouheif, E. A method for testing the assumption of phylogenetic independence in comparative data. Evol. Ecol. Res. 1999, 1, 895–909. [Google Scholar]

- Münkemüller, T.; Lavergne, S.; Bzeznik, B.; Dray, S.; Jombart, T.; Schiffers, K.; Thuiller, W. How to measure and test phylogenetic signal. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 3, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freckleton, R.P.; Harvey, P.H.; Pagel, M. Phylogenetic analysis and comparative data: A test and review of evidence. Am. Nat. 2002, 160, 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comte, L.; Murienne, J.; Grenouillet, G. Species traits and phylogenetic conservatism of climate-induced range shifts in stream fishes. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keck, F.; Rimet, F.; Franc, A.; Bouchez, A. Phylogenetic signal in diatom ecology: Perspectives for aquatic ecosystems biomonitoring. Ecol. Appl. 2016, 26, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lymberakis, P.; Poulakakis, N.; Kaliontzopoulou, A.; Valakos, E.; Mylonas, M. Two new species of Podarcis (Squamata; Lacertidae) from Greece. Syst. Biodivers. 2008, 6, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCue, M. General Effects of Temperature on Animal Biology; Smithsonian Books: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Angilletta, M.J.J.; Steury, T.D.; Sears, M.W. Temperature, growth rate, and body size in ectotherms: Fitting pieces of a life-history puzzle. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2004, 44, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vervust, B.; Pafilis, P.; Valakos, E.D.; Van Damme, R. Anatomical and physiological changes associated with a recent dietary shift in the lizard Podarcis sicula. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2010, 83, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemany, I.; Pérez-Cembranos, A.; Pérez-Mellado, V.; Castro, J.A.; Picornell, A.; Ramon, C.; Jurado-Rivera, J.A. DNA metabarcoding the diet of Podarcis lizards endemic to the Balearic Islands. Curr. Zool. 2022, 69, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runemark, A.; Sagonas, K.; Svensson, E.I. Ecological explanations to island gigantism: Dietary niche divergence, predation, and size in an endemic lizard. Ecology 2015, 96, 2077–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacheva, E.; Naumov, B. Some insights into the diet of the Balkan wall lizard Podarcis tauricus (Pallas, 1814) in northwestern Bulgaria. Biharean Biol. 2024, 18, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Taverne, M.; Fabre, A.-C.; King-Gillies, N.; Krajnović, M.; Lisičić, D.; Martin, L.; Michal, L.; Petricioli, D.; Štambuk, A.; Tadić, Z.; et al. Diet variability among insular populations of Podarcis lizards reveals diverse strategies to face resource-limited environments. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 12408–12420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, J.T.; Fuhlendorf, S.D.; Davis, C.A.; Wilder, S.M. Arthropod prey vary among orders in their nutrient and exoskeleton content. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 17774–17785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, E.; Baraniak, B.; Karaś, M.; Rybczyńska, K.; Jakubczyk, A. Selected species of edible insects as a source of nutrient composition. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouřimská, L.; Adámková, A. Nutritional and sensory quality of edible insects. NFS J. 2016, 4, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huis, A.; Van Itterbeeck, J.; Klunder, H.; Mertens, E.; Halloran, A.; Muir, G.; Vantomme, P. Edible Insects Future Prospects for Food and Feed Security; Food And Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2013; Volume 171. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, S.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, R.; Yang, Y. Digestive tract morphology and argyrophil cell distribution of three sympatric lizard species. Eur. Zool. J. 2024, 91, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyer, K. Structure and Function of the Digestive Tract of a Herbivorous Lizard Iguana iguana. Physiol. Zool. 1984, 57, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, B.; Sharma, R. The digestive system. In Embryology, 2nd ed.; Mitchell, B., Sharma, R., Eds.; Churchill Livingstone: London, UK, 2009; pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Karasov, W.H.; Petrossian, E.; Rosenberg, L.; Diamond, J.M. How do food passage rate and assimilation differ between herbivorous lizards and nonruminant mammals? J. Comp. Physiol. B 1986, 156, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaupre, S.; Dunham, A.; Overall, K. The Effects of Consumption Rate and Temperature on Apparent Digestibility Coefficient, Urate Production, Metabolizable Energy Coefficient and Passage Time in Canyon Lizards (Sceloporus merriami) from Two Populations. Funct. Ecol. 1993, 7, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnachie, S.; Alexander, G.J. The effect of temperature on digestive and assimilation efficiency, gut passage time and appetite in an ambush foraging lizard, Cordylus melanotus melanotus. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2004, 174, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Guillén, C.; Yúfera, M.; Perera, E. Biochemical features and modulation of digestive enzymes by environmental temperature in the greater amberjack, Seriola dumerili. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 960746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungate, R.E. The Rumen and Its Microbes; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood, R.H. The effect of temperature on the digestive efficiency of three species of lizards, Cnemidophorus tigris, Gerrhonotus multicarinatus and Sceloporus occidentalis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A 1979, 63, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, R.M.; Danson, M.J.; Eisenthal, R. The temperature optima of enzymes: A new perspective on an old phenomenon. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001, 26, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabat, P.; Božinović, F. Dietary chemistry and allometry of intestinal disaccharidases in the toad Bufo spinulosus. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 1996, 69, 387–391. [Google Scholar]

- Naya, D.E.; Farfán, G.; Sabat, P.; Méndez, M.A.; Bozinovic, F. Digestive morphology and enzyme activity in the Andean toad Bufo spinulosus: Hard-wired or flexible physiology? Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A 2005, 140, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, O.; Altirriba, J.; Rigo, D.; Spiljar, M.; Evrard, E.; Roska, B.; Fabbiano, S.; Zamboni, N.; Maechler, P.; Rohner-Jeanrenaud, F.; et al. Dietary excess regulates absorption and surface of gut epithelium through intestinal PPARα. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmberg, A.; Kaim, J.; Persson, A.; Jensen, J.; Wang, T.; Holmgren, S. Effects of digestive status on the reptilian gut. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2002, 133, 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.M. Reptiles and Herbivory; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Berne, R.M.; Levy, M.N. Principles of Physiology, 2nd ed.; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bakala N’Goma, J.C.; Amara, S.; Dridi, K.; Jannin, V.; Carrière, F. Understanding the lipid-digestion processes in the GI tract before designing lipid-based drug-delivery systems. Ther. Deliv. 2012, 3, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanso, L.S. Gastrointestinal physiology. In Physiology, 6th ed.; Costanso, L.S., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 339–393. [Google Scholar]

- Karasov, W.H.; Douglas, A.E. Comparative digestive physiology. Compr. Physiol. 2013, 3, 741–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donihue, C.M.; Brock, K.M.; Foufopoulos, J.; Herrel, A. Feed or fight: Testing the impact of food availability and intraspecific aggression on the functional ecology of an island lizard. Funct. Ecol. 2015, 30, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinoni, S.A.; Iribarne, O.; Mañanes, A.A.L. Between-habitat comparison of digestive enzymes activities and energy reserves in the SW Atlantic euryhaline burrowing crab Neohelice granulata. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2011, 158, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, N.; Kikumori, A.; Kawase, D.; Okano, M.; Fukamachi, K.; Ishida, T.; Nakajima, K.; Shiomi, M. Species differences in lipoprotein lipase and hepatic lipase activities: Comparative studies of animal models of lifestyle-related diseases. Exp. Anim. 2019, 68, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clissold, F.J.; Brown, Z.P.; Simpson, S.J. Protein-induced mass increase of the gastrointestinal tract of locusts improves net nutrient uptake via larger meals rather than more efficient nutrient absorption. J. Exp. Biol. 2013, 216, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, J.; Lundstedt, L.; Inoue, L. Effect of different concentrations of protein on the digestive system of juvenile silver catfish. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2012, 64, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, E.; Michiels, M.S.; López-Mañanes, A.A. The influence of habitat on metabolic and digestive parameters in an intertidal crab from a SW Atlantic coastal lagoon. Belg. J. Zool. 2021, 151, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senti, T.; Gifford, M. Seasonal and taxonomic variation in arthropod macronutrient content. Food Webs 2024, 38, e00328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macierzanka, A.; Torcello-Gómez, A.; Jungnickel, C.; Maldonado-Valderrama, J. Bile salts in digestion and transport of lipids. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 274, 102045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, E.; Jakob, S.; Mosenthin, R. Principles of Physiology of Lipid Digestion. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 18, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrle, B.A.; German, D.P. Reptilian digestive efficiency: Past, present, and future. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2023, 277, 111369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikelski, M.; Cooke, S.J. Conservation physiology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2006, 21, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trait | Cmean | p-Value | λ | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Length (SVL) | 0.309 | 0.019 | 0.001 | 0.999 |

| Body Mass | −0.056 | 0.279 | 0.001 | 0.999 |

| GI Tract Length | 0.193 | 0.027 | 0.001 | 0.999 |

| GI Tract Mass | −0.115 | 0.347 | 0.001 | 0.999 |

| Protease Activity | −0.042 | 0.234 | 0.001 | 0.999 |

| Lipase Activity | −0.167 | 0.489 | 0.001 | 0.999 |

| Maltase Activity | −0.157 | 0.557 | 0.001 | 0.999 |

| ADEPR | −0.069 | 0.311 | 0.001 | 0.999 |

| ADESUG | −0.051 | 0.263 | 0.452 | 0.999 |

| Gut Passage Time | −0.133 | 0.414 | 0.001 | 0.999 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sagonas, K.; Paraskevopoulou, F.; Kotsakiozi, P.; Sozopoulos, I.; Pafilis, P.; Valakos, E.D. Digestive Enzyme Activity and Temperature: Evolutionary Constraint or Physiological Flexibility? Animals 2026, 16, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010100

Sagonas K, Paraskevopoulou F, Kotsakiozi P, Sozopoulos I, Pafilis P, Valakos ED. Digestive Enzyme Activity and Temperature: Evolutionary Constraint or Physiological Flexibility? Animals. 2026; 16(1):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010100

Chicago/Turabian StyleSagonas, Konstantinos, Foteini Paraskevopoulou, Panayiota Kotsakiozi, Ilias Sozopoulos, Panayiotis Pafilis, and Efstratios D. Valakos. 2026. "Digestive Enzyme Activity and Temperature: Evolutionary Constraint or Physiological Flexibility?" Animals 16, no. 1: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010100

APA StyleSagonas, K., Paraskevopoulou, F., Kotsakiozi, P., Sozopoulos, I., Pafilis, P., & Valakos, E. D. (2026). Digestive Enzyme Activity and Temperature: Evolutionary Constraint or Physiological Flexibility? Animals, 16(1), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010100