Artificial Neural Networks for Predicting Emissions from the Livestock Sector: A Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Aims and Methodology

2.1. Research Needs and Research Questions

- RQ1.

- What is the regional distribution of the bibliographic research?

- RQ2.

- What are the ANN applications and devices applied in gas estimation?

- RQ3.

- What types of species and livestock management are the most investigated?

- RQ4.

- Which ANN structures are prevalent and minor in current approaches?

- RQ5.

- What are the characteristics (i.e., pre-processing, timeframe, parameters, temporal evolution) of the datasets that are predominantly used?

- RQ6.

- What type of evaluation metrics have been applied?

- RQ7.

- Which ANN training algorithms have been used?

- RQ8.

- Which comparisons have been made among statistical, ML, and ANN approaches in the reviewed articles?

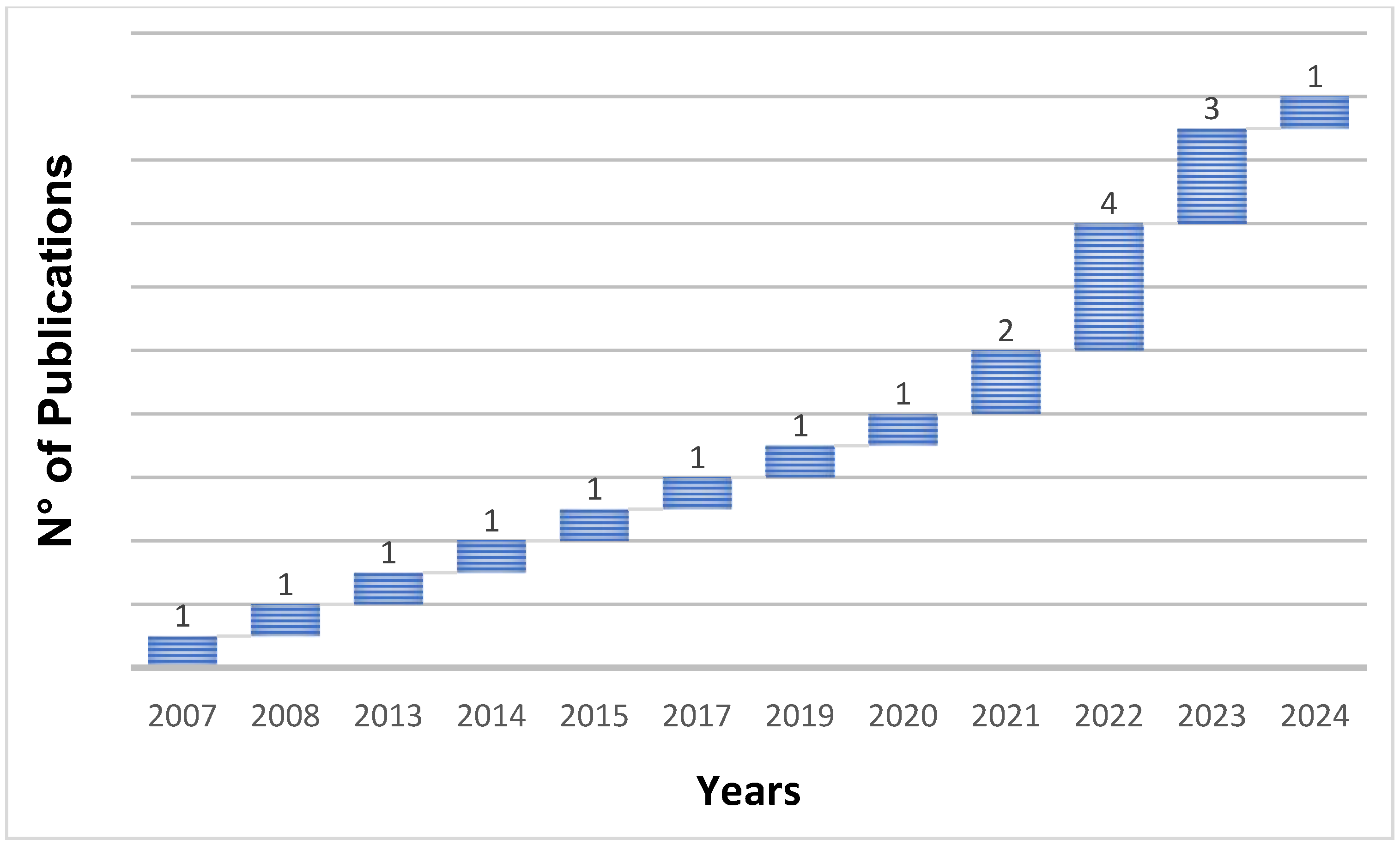

2.2. Review Development Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Articles Geographical Distribution and Bibliographic Cluster Analysis (RQ1)

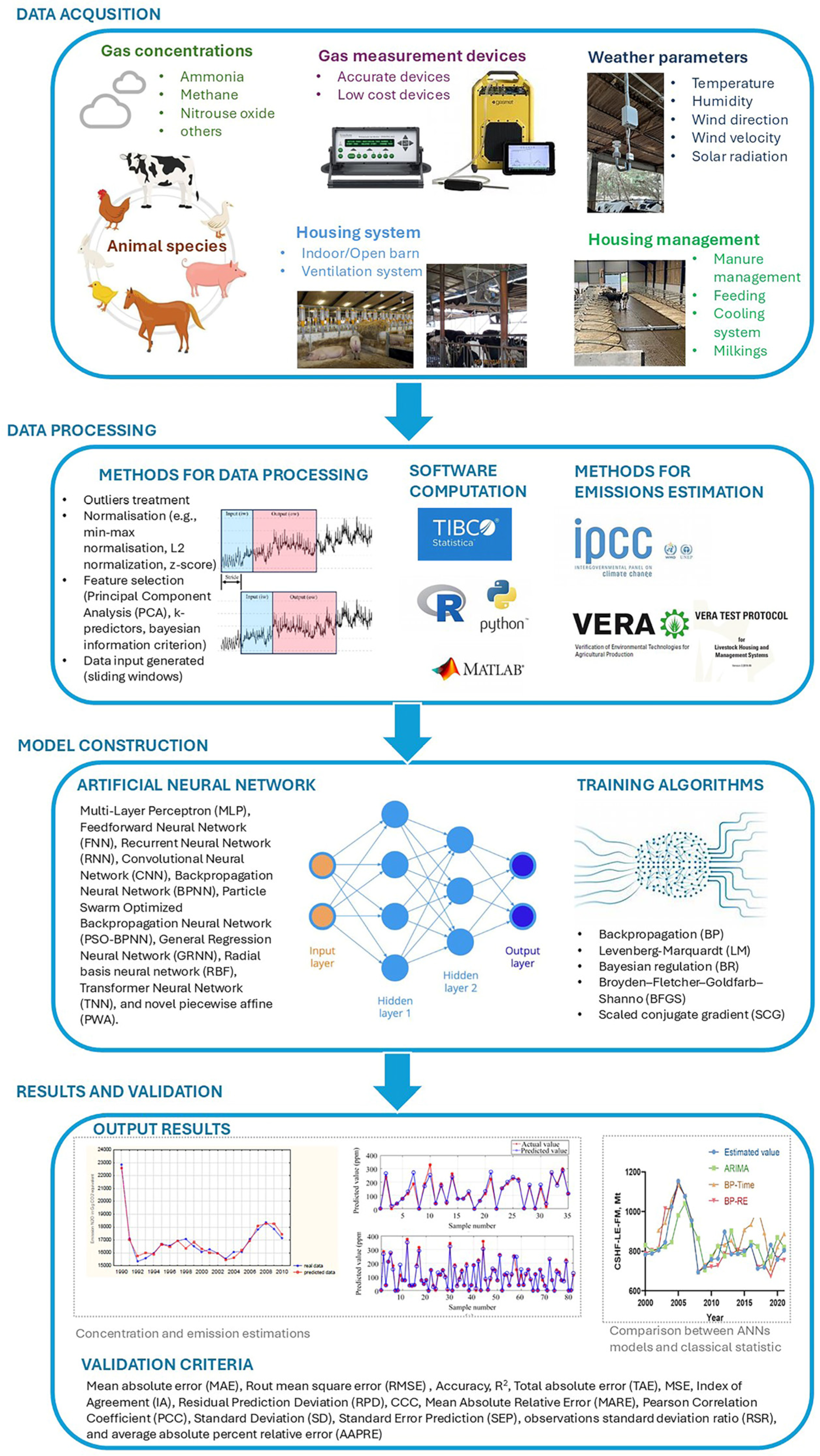

3.2. ANN Applications to Livestock Production: Gases and Measurement Systems (RQ2)

3.3. Livestock Species Involved, Housing System, and Building Characteristics (RQ3)

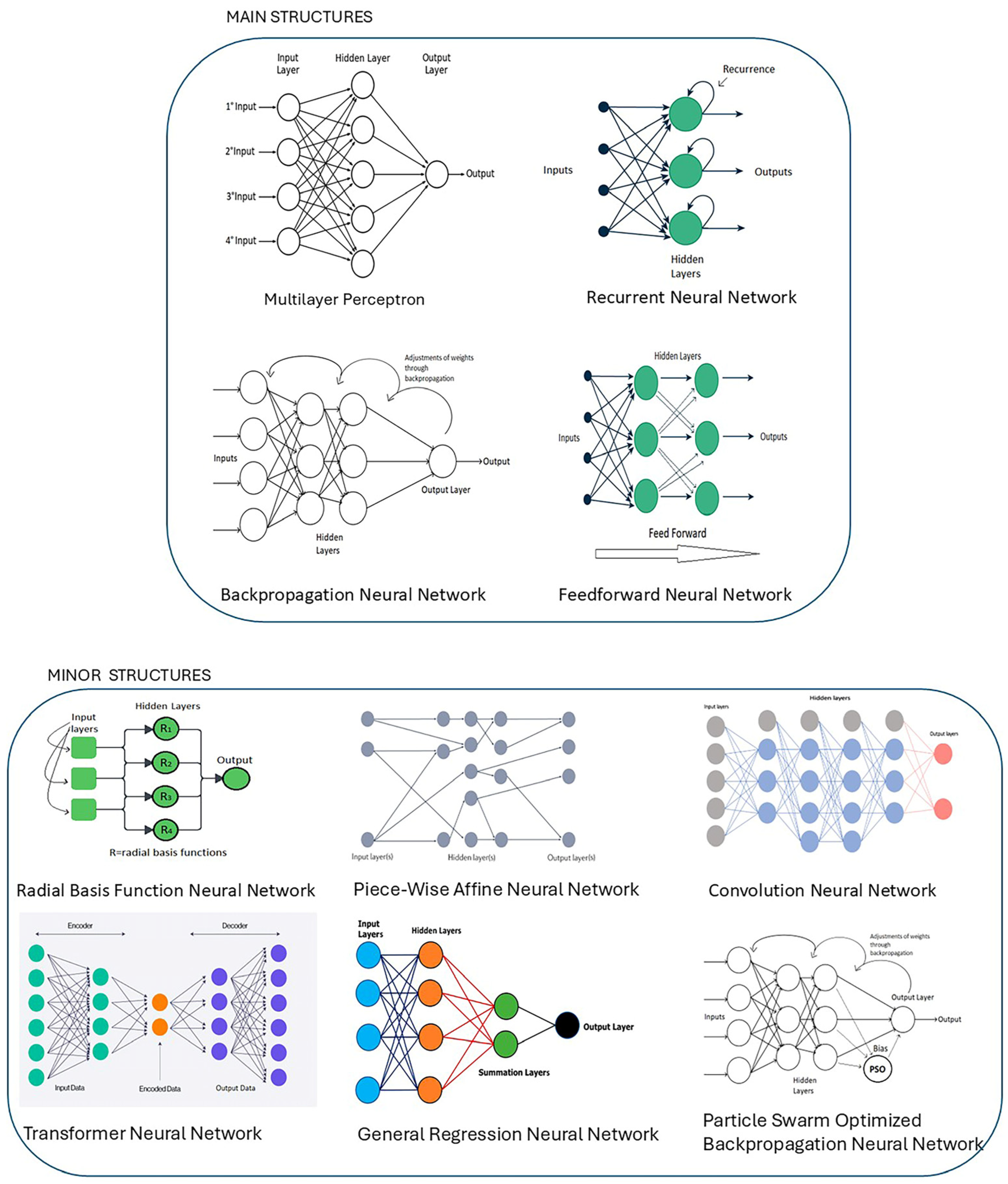

3.4. Prevalent and Minor ANN Structures (RQ4)

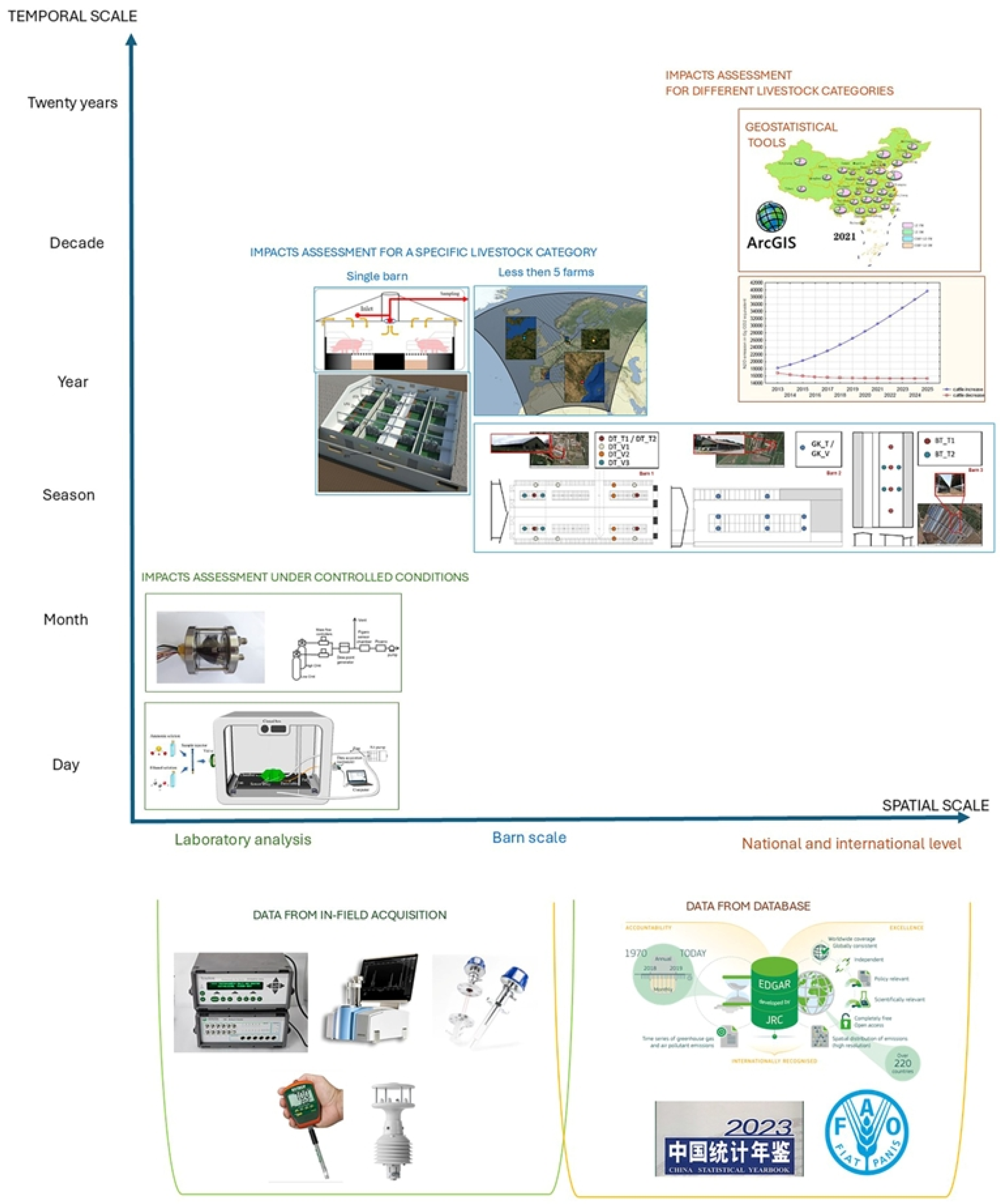

3.5. Dataset Characteristics (RQ5)

3.6. Evaluation Metrics Applied (RQ6)

3.7. ANN Training Algorithms Applied (RQ7)

3.8. Comparisons Among Methodologies Based on Statistical, ML, and ANN Models (RQ8)

4. Discussion Overview

4.1. The Role of ANNs in Concentration and Emission Estimation

4.2. ANN Characteristics and Datasets Applied

4.3. Future ANN Applications and Research Needs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NH3 | Ammonia |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| PLF | Precision Livestock Farming |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| CH4 | Methane |

References

- Khade, S.B.; Khillare, R.S.; Dastagiri, M.B. Global livestock development: Policies and vision. Indian J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 91, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosire, C.K.; Mtimet, N.; Enahoro, D.; Ogutu, J.O.; Krol, M.S.; De Leeuw, J.; Ndiwa, N.; Hoekstra, A.Y. Livestock water and land productivity in Kenya and their implications for future resource use. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, T.; White, R. Breeding animals to feed people: The many roles of animal reproduction in ensuring global food security. Theriogenology 2020, 150, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivero, M.J.; Lopez-Villalobos, N.; Evans, A.; Berndt, A.; Cartmill, A.; Neal, A.L.; McLaren, A.; Farruggia, A.; Mignolet, C.; Chadwick, D.; et al. Key traits for ruminant livestock across diverse production systems in the context of climate change: Perspectives from a global platform of research farms. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2021, 33, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yitbarek, M.B. Livestock and livestock product trends by 2050. IJAR 2019, 4, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, T.; Abbasi, T.; Abbasi, S. Reducing the global environmental impact of livestock production: The minilivestock option. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1754–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronberg, S.L.; Ryschawy, J. Negative impacts on the environment and people from simplification of crop and livestock production. In Agroecosystem Diversity; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, M.; de Boer, I. Comparing environmental impacts for livestock products: A review of life cycle assessments. Livest. Sci. 2010, 128, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraham, S.J. Environmental impacts of industrial livestock production. In International Farm Animal, Wildlife and Food Safety Law; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llonch, P.; Haskell, M.J.; Dewhurst, R.J.; Turner, S.P. Current available strategies to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions in livestock systems: An animal welfare perspective. Animal 2017, 11, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, R.; Jo, S.; Lee, J.; Khanthong, K.; Jang, H.; Park, J. A review on the anaerobic co-digestion of livestock manures in the context of sustainable waste management. Energies 2024, 17, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhao, B.; Jia, Y.; He, F.; Chen, W. Mitigation strategies of air pollutants for mechanical ventilated livestock and poultry housing—A review. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prathap, P.; Chauhan, S.S.; Leury, B.J.; Cottrell, J.J.; Dunshea, F.R. Towards sustainable livestock production: Estimation of methane emissions and dietary interventions for mitigation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, M.; Solazzo, E.; Guizzardi, D.; Van Dingenen, R.; Leip, A. Air pollutant emissions from global food systems are responsible for environmental impacts, crop losses and mortality. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 942–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghassemi Nejad, J.G.; Ju, M.-S.; Jo, J.-H.; Oh, K.-H.; Lee, Y.-S.; Lee, S.-D.; Kim, E.-J.; Roh, S.; Lee, H.-G. Advances in Methane Emission Estimation in Livestock: A Review of Data Collection Methods, Model Development and the Role of AI Technologies. Animals 2024, 14, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, L.O.; Abdalla, A.L.; Álvarez, C.; Anuga, S.W.; Arango, J.; Beauchemin, K.A.; Becquet, P.; Berndt, A.; Burns, R.; De Camillis, C.; et al. Quantification of methane emitted by ruminants: A review of methods. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, skac197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikiru, A.; Michael, A.O.; John, M.O.; Egena, S.S.A.; Oleforuh-Okoleh, V.U.; Ambali, M.I.; Muhammad, I.R. Methane emissions in cattle production: Biology, measurement and mitigation strategies in smallholder farmer systems. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 27, 29263–29286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berckmans, D. General introduction to precision livestock farming. Anim. Front. 2017, 7, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.; Brown Brandl, T.; Panogakis, P.; Cruz, V.; Diefes-Dux, H.; Calvet, S. Educating for Precision Livestock Farming: The Knowledge, Skills and Abilities to Meet Future Industry and Societal Needs. In Proceedings of the 10th European Conference on Precision Livestock Farming (ECPLF), Vienna, Austria, 5–8 September 2022; pp. 186–192, ISBN 978-83-965360-0-6. [Google Scholar]

- Arcidiacono, C.; Mancino, M.; Porto, S.; Bloch, V.; Pastell, M. IoT device-based data acquisition system with on-board computation of variables for cow behaviour recognition. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 191, 106500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melak, A.; Aseged, T.; Shitaw, T. The Influence of Artificial Intelligence Technology on the Management of Livestock Farms. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2024, 2024, 8929748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, J.M.; Swiergosz, A.M.; Haeberle, H.S.; Karnuta, J.M.; Schaffer, J.L.; Krebs, V.E.; Spitzer, A.I.; Ramkumar, P.N. Machine learning and artificial intelligence: Definitions, applications, and future directions. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2020, 13, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.K.; Ahneman, D.T.; Riera, O.; Doyle, A.G. Deoxyfluorination with sulfonyl fluorides: Navigating reaction space with machine learning. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 5004–5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijwil, M.M.; Adelaja, O.; Badr, A.; Ali, G.; Buruga, B.A.; Pudasaini, P. Innovative Livestock: A Survey of Artificial Intelligence Techniques in Livestock Farming Management. Wasit J. Comput. Math. Sci. 2023, 2, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Mitnitski, A.; Cox, J.; Rockwood, K. Comparison of Machine Learning Techniques with Classical Statistical Models in Predicting Health Outcomes. In MEDINFO 2004: Proceedings of the 11th World Congress on Medical Informatics, San Francisco, CA, USA, 7–11 September 2004; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 736–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, P.R.; Arcidiacono, C.; Cascone, G. Ammonia and greenhouse gas distribution in a dairy barn during warm periods. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2024, 11, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.R.; Silva, M.E.; Silva, V.F.; Maia, M.R.; Cabrita, A.R.; Trindade, H.; Fonseca, A.J.; Pereira, J.L. Implications of seasonal and daily variation on methane and ammonia emissions from naturally ventilated dairy cattle barns in a Mediterranean climate: A two-year study. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 173734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hempel, S.; Saha, C.K.; Fiedler, M.; Berg, W.; Hansen, C.; Amon, B.; Amon, T. Non-linear temperature dependency of ammonia and methane emissions from a naturally ventilated dairy barn. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 145, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, K.; Decuypere, E.; DE Baerdemaeker, J.; DE Ketelaere, B. Statistical control charts as a support tool for the management of livestock production. J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 149, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossen, P. An analysis of agricultural livestock and traditional crop production statistics as a function of total annual and early, mid and late rainy season rainfall in Botswana. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1988, 42, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayeri, S.; Sargolzaei, M.; Tulpan, D. A review of traditional and machine learning methods applied to animal breeding. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2019, 20, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, R.; Aguilar, J.; Toro, M.; Pinto, A.; Rodríguez, P. A systematic literature review on the use of machine learning in precision livestock farming. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 179, 105826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, M. Application and prospective discussion of machine learning for the management of dairy farms. Animals 2020, 10, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, R.; Largouët, C.; Dourmad, J.-Y. Prediction of litter performance in lactating sows using machine learning, for precision livestock farming. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 196, 106876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M.; Nasrabadi, N.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 4, p. 738. ISBN 978-0387-31073-2. [Google Scholar]

- Liakos, K.G.; Busato, P.; Moshou, D.; Pearson, S.; Bochtis, D. Machine learning in agriculture: A review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krenker, A.; Bester, J.; Kos, A. Introduction to the Artificial Neural Networks. In Artificial Neural Networks: Methodological Advances and Biomedical Applications; InTech: London, UK, 2011; pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-953-307-243-2. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Yuan, F.; Ata-Ul-Karim, S.T.; Liu, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; Cao, Q. A bibliometric analysis of research on remote sensing-based monitoring of soil organic matter conducted between 2003 and 2023. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2025, 15, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiodun, O.I.; Jantan, A.; Omolara, A.E.; Dada, K.V.; Mohamed, N.A.; Arshad, H. State-of-the-art in artificial neural network applications: A survey. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-C.; Feng, J.-W. Development and application of artificial neural network. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2018, 102, 1645–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, R.; Patel, J.K.; Manry, M.T. Minimizing validation error with respect to network size and number of training epochs. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Dallas, TX, USA, 4–9 August 2013; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shine, P.; Murphy, M.D. Over 20 years of machine learning applications on dairy farms: A comprehensive mapping study. Sensors 2021, 22, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Mandal, A.; Gayari, I.; Bidyalaxmi, K.; Sarkar, D.; Allu, T.; Debbarma, A. Prospect and scope of artificial neural network in livestock farming: A review. Biol. Rhythm. Res. 2023, 54, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallerla, C.; Feng, Y.; Owens, C.M.; Bist, R.B.; Mahmoudi, S.; Sohrabipour, P.; Davar, A.; Wang, D. Neural network architecture search enabled wide–deep learning (NAS–WD) for spatially heterogenous property awared chicken woody breast classification and hardness regression. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2024, 14, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Gao, X.X.; Hou, Z. Low-cost livestock sorting information management system based on deep learning. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2023, 9, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresolin, T.; Dórea, J.R.R. Infrared spectrometry as a high-throughput phenotyping technology to predict complex traits in livestock systems. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Liu, Y.; Tang, R.L.; Ma, R.N.; Li, G.X. A review of carbon and nitrogen losses and greenhouse gas emissions during livestock manure composting. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2021, 40, 2428–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitau, J.K.; Macharia, R.W.; Mwangi, K.W.; Ongeso, N.; Murungi, E. Gene co-expression network identifies critical genes, pathways and regulatory motifs mediating the progression of rift valley fever in Bostaurus. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Wei, W.; Das, R.; Chatterjee, T. Analysis of the Strategic Emission-Based Energy Policies of Developing and Developed Economies with Twin Prediction Model. Complexity 2020, 2020, 4701678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, I.; van der Weerden, T.J.; Alfaro, M.A.; Amon, B.; de Klein, C.A.M.; Grace, P.; Hafner, S.; Hassouna, M.; Hutchings, N.; Krol, D.J.; et al. DATAMAN: A global database of nitrous oxide and ammonia emission factors for excreta deposited by livestock and land-applied manure. J. Environ. Qual. 2021, 50, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassouna, M.; van der Weerden, T.J.; Beltran, I.; Amon, B.; Alfaro, M.A.; Anestis, V.; Cinar, G.; Dragoni, F.; Hutchings, N.J.; Leytem, A.; et al. DATAMAN: A global database of methane, nitrous oxide, and ammonia emission factors for livestock housing and outdoor storage of manure. J. Environ. Qual. 2023, 52, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Aardenne, J.A.; Kroeze, C.; Pulles, M.P.J.; Hordijk, L. Uncertainties in the calculation of agricultural N2O emissions in The Netherlands using IPCC Guidelines. In Non-CO2 Greenhouse Gases: Scientific Understanding, Control and Implementation: Proceedings of the Second International Symposium, Noordwijkerhout, The Netherlands, 8–10 September 1999; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, C.; Misselbrook, T.H.; Vega, A.; Gonzalez-Quintero, R.; Chavarro-Lobo, J.A.; Mazzetto, A.M.; Chadwick, D.R. Measured ammonia emissions from tropical and subtropical pastures: A comparison with 2006 IPCC, 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC, and EMEP/EEA (European Monitoring and Evaluation Programme and European Environmental Agency) inventory estimates. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 6706–6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kwak, Y.; Huh, J.-H. Long-term performance validation of NH3 concentration prediction model for virtual sensor application in livestock facility. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, L.V. Global observed long-term changes in temperature and precipitation extremes: A review of progress and limitations in IPCC assessments and beyond. Weather. Clim. Extremes 2016, 11, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niloofar, P.; Francis, D.P.; Lazarova-Molnar, S.; Vulpe, A.; Vochin, M.-C.; Suciu, G.; Balanescu, M.; Anestis, V.; Bartzanas, T. Data-driven decision support in livestock farming for improved animal health, welfare, and greenhouse gas emissions: Overview and challenges. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 190, 106406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, E.K.; Malek, M.A.; Shamsuddin, S.M. Artificial intelligence projection model for methane emission from livestock in Sarawak. Sains Malays. 2019, 48, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolasa-Więcek, A. Neural modeling of greenhouse gas emission from agricultural sector in European Union member countries. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2018, 229, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonori, S.; Baldini, L.; Rizzi, A.; Frattale Mascioli, F.M. A physically inspired equivalent neural network circuit model for SOC estimation of electrochemical cells. Energies 2021, 14, 7386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zheng, H.; Wang, H.; Yan, T. Can machine learning algorithms perform better than multiple linear regression in predicting nitrogen excretion from lactating dairy cows. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolasa-Więcek, A. A Use of artificial neural networks in predicting direct nitrous oxide emissions from agricultural soils. Ecol. Chem. Eng. S 2013, 20, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, R.R.; Santaren, D.; Laurent, O.; Cropley, F.; Mallet, C.; Ramonet, M.; Caldow, C.; Rivier, L.; Broquet, G.; Bouchet, C.; et al. The potential of low-cost tin-oxide sensors combined with machine learning for estimating atmospheric CH4 variations around background concentration. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovanh, N.; Quintanar, A.; Rysz, M.; Loughrin, J.; Mahmood, R. Effect of heat fluxes on ammonia emission from swine waste lagoon based on neural network analyses 2014. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 7, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Hoff, S.J.; Zelle, B.C.; Nelson, M.A. Forecasting daily source air quality using multivariate statistical analysis and radial basis function networks. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2008, 58, 1571–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.; Moon, Y.-S.; Kim, T.-W. Artificial neural network approach for prediction of ammonia emission from field-applied manure and relative significance assessment of ammonia emission factors. Eur. J. Agron. 2007, 26, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, S.; Adolphs, J.; Landwehr, N.; Janke, D.; Amon, T. How the selection of training data and modelling approach affects the estimation of ammonia emissions from a naturally ventilated dairy barn—Classical statistics versus machine learning. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, S.; Menz, C.; Pinto, S.; Galán, E.; Janke, D.; Estellés, F.; Müschner-Siemens, T.; Wang, X.; Heinicke, J.; Zhang, G.; et al. Heat stress risk in European dairy cattle husbandry under different climate change scenarios—Uncertainties and potential impacts. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2019, 10, 859–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Sheng, J. Estimation of Manure Emissions Issued from Different Chinese Livestock Species: Potential of Future Production. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçüktopcu, E.; Cemek, B. The use of artificial neural networks to estimate optimum insulation thickness, energy savings, and carbon dioxide emissions. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2021, 40, e13478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, J.K.; Arulmozhi, E.; Moon, B.E.; Bhujel, A.; Kim, H.T. Modelling methane emissions from pig manure using statistical and machine learning methods. Air Qual. Atmosphere Health 2022, 15, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Jo, G.; Jung, M.; Oh, Y. Comparative Analysis of Neural Network Models for Predicting Ammonia Concentrations in a Mechanically Ventilated Sow Gestation Facility in Korea. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genedy, R.A.; Chung, M.; Shortridge, J.E.; Ogejo, J.A. A physics-informed long short-term memory (LSTM) model for estimating ammonia emissions from dairy manure during storage. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 912, 168885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besteiro, R.; Arango, T.; Ortega, J.A.; Rodríguez, M.R.; Fernández, M.D.; Velo, R. Prediction of carbon dioxide concentration in weaned piglet buildings by wavelet neural network models. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 143, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Shi, Y.; Niu, H.; Liu, J.; Sun, P. Structure Optimization and Data Processing Method of Electronic Nose Bionic Chamber for Detecting Ammonia Emissions from Livestock Excrement Fermentation. Sensors 2024, 24, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamenković, L.J.; Antanasijević, D.Z.; Ristić, M.Đ.; Perić-Grujić, A.A.; Pocajt, V.V. Modelling of methane emissions using the artificial neural network approach. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2015, 80, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadpour, S.; Chud, T.C.; Hailemariam, D.; Plastow, G.; Oliveira, H.R.; Stothard, P.; Lassen, J.; Miglior, F.; Baes, C.F.; Tulpan, D.; et al. Predicting methane emission in Canadian Holstein dairy cattle using milk mid-infrared reflectance spectroscopy and other commonly available predictors via artificial neural networks. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 8272–8285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Z.; Hu, B.; Wang, M.; Pu, S. Prediction of ammonia concentration in a pig house based on machine learning models and environmental parameters. Animals 2022, 13, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, J.; Modell, H. Validating the core concept of “mass balance”. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2021, 45, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buberger, J.; Kersten, A.; Kuder, M.; Eckerle, R.; Weyh, T.; Thiringer, T. Total CO2-equivalent life-cycle emissions from commercially available passenger cars. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, M.W.; Dorling, S.R. Artificial neural networks (the multilayer perceptron)—A review of applications in the atmospheric sciences. Atmos. Environ. 1998, 32, 2627–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, V.K.; Abraham, A.; Snášel, V. Metaheuristic design of feedforward neural networks: A review of two decades of research. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2017, 60, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, Z.C. A Critical Review of Recurrent Neural Networks for Sequence Learning. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.00019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, A.; Verma, G.K. Convolutional neural network: A review of models, methodologies and applications to object detection. Prog. Artif. Intell. 2020, 9, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscema, M. Back propagation neural networks. Subst. Use Misuse 1998, 33, 233–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liang, R.; Qi, Y.; Cui, X.; Liu, J. Prediction model of spontaneous combustion risk of extraction borehole based on PSO–BPNN and its application. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.T.; Chen, A.-S.; Daouk, H. Forecasting exchange rates using general regression neural networks. Comput. Oper. Res. 2000, 27, 1093–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Cai, X.; Feng, M. The Evaluation of Course Teaching Effect Based on Improved RBF Neural Network. Syst. Soft Comput. 2024, 6, 200085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30, ISBN 9781510860964. [Google Scholar]

- Jouret, L.; Saoud, A.; Olaru, S. Safety verification of Neural-Network-based controllers: A set invariance approach. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2023, 7, 3842–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touretzky, D.S.; Pomerleau, D.A. What’s hidden in the hidden layers. Byte 1989, 14, 227–233. [Google Scholar]

- Stathakis, D. How many hidden layers and nodes. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2009, 30, 2133–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökhan, A.K.S.U.; Güzeller, C.O.; Eser, M.T. The effect of the normalization method used in different sample sizes on the success of artificial neural network model. Int. J. Assess. Tools Educ. 2019, 6, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floreano, D.; Mattiussi, C. Manuale Sulle Reti Neurali; Il Mulino: Milan, Italy, 2002; ISBN 9788815085047. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmeir, C. Common Pitfalls and Better Practices in Forecast Evaluation for Data Scientists. Foresight Int. J. Appl. Forecast. 2023, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, J.J.M. Artificial neural networks applied to forecasting time series. Psicothema 2011, 23, 322–329. [Google Scholar]

- Wibawa, A.P.; Utama, A.B.P.; Elmunsyah, H.; Pujianto, U.; Dwiyanto, F.A.; Hernandez, L. Time-series analysis with smoothed Convolutional Neural Network. J. Big Data 2022, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilamowski, B.M. Neural network architectures and learning algorithms. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2009, 3, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.-S.; Lee, H.; Tahk, M.-J. Acceleration of the convergence speed of evolutionary algorithms using multi-layer neural networks. Eng. Optim. 2003, 35, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, J. What is the Difference Between a Batch and an Epoch in a Neural Network. Mach. Learn. Mastery 2018, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffmann, W.; Joost, M.; Werner, R. Optimization of the Backpropagation Algorithm for Training Multilayer Perceptrons; Germany University of Koblenz, Institute of Physics: Koblenz, Germany, 1994; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wythoff, B.J. Backpropagation neural networks: A tutorial. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 1993, 18, 115–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdoğan, H.; Üncü, Y.A.; Şekerci, M.; Kaplan, A. Neural network predictions of (α, n) reaction cross sections at 18.5±3 MeV using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2024, 204, 111115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Qin, Y.; Liu, K.; Yuan, G. Biased stochastic conjugate gradient algorithm with adaptive step size for nonconvex problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 238, 121556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, F.; Winkler, D. Bayesian Regularization of Neural Networks. Artif. Neural Netw. Methods Appl. 2009, 458, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-Y.; Huang, Y.; Nguyen, V.P. On the BFGS monolithic algorithm for the unified phase field damage theory. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2020, 360, 112704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czubak, W.; Pawłowski, K.P.; Sadowski, A. Outcomes of farm investment in Central and Eastern Europe: The role of financial public support and investment scale. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, D.; Willink, D.; Ammon, C.; Hempel, S.; Schrade, S.; Demeyer, P.; Hartung, E.; Amon, B.; Ogink, N.; Amon, T. Calculation of ventilation rates and ammonia emissions: Comparison of sampling strategies for a naturally ventilated dairy barn. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 198, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VERA. Vera Test Protocol: For Livestock Housing and Management Systems; International VERA Secretariat: Delft, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bjerg, B.S.; Demeyer, P.; Hoyaux, J.; Mislav, D.; Juha, G.; Mélynda, H.; Barbara, A.; Bartzanas, T.; Sándor, R.; Fogarty, M.P.; et al. Review of legal requirements on ammonia and greenhouse gases emissions from animal production buildings in European countries. 2019 ASABE Annual International Meeting, Boston, MA, USA, 7–10 July 2019; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2019; p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Arendonk, J.A.; Liinamo, A.-E. Dairy cattle production in Europe. Theriogenology 2003, 59, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullo, E.; Finzi, A.; Guarino, M. Environmental impact of livestock farming and Precision Livestock Farming as a mitigation strategy. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 650, 2751–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovarelli, D.; Bacenetti, J.; Guarino, M. A review on dairy cattle farming: Is precision livestock farming the compromise for an environmental, economic and social sustainable production? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M.; Bava, L.; Sandrucci, A.; Tangorra, F.; Tamburini, A.; Gislon, G.; Zucali, M. Diffusion of precision livestock farming technologies in dairy cattle farms. Animal 2022, 16, 100650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malherbe, L.; German, R.; Couvidat, F.; Zanatta, L.; Blannin, L.; James, A.; Lètinois, L.; Schucht, S.; Berthelot, B.; Raoult, J. Emissions of ammonia and methane from the agricultural sector. In Emissions from Livestock Farming (Eionet Report—ETC HE 2022/21); European Topic Centre on Human Health and the Environment: Kjeller, Norway, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- D’urso, P.R.; Arcidiacono, C.; Cascone, G. Analysis of the Horizontal Distribution of Sampling Points for Gas Concentrations Monitoring in an Open-Sided Dairy Barn. Animals 2022, 12, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’urso, P.R.; Arcidiacono, C.; Cascone, G. Assessment of a low-cost portable device for gas concentration monitoring in livestock housing. Agronomy 2022, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ndegwa, P.M.; Joo, H.; Neerackal, G.M.; Harrison, J.H.; Stöckle, C.O.; Liu, H. Reliable low-cost devices for monitoring ammonia concentrations and emissions in naturally ventilated dairy barns. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 208, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neethirajan, S. The role of sensors, big data and machine learning in modern animal farming. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2020, 29, 100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; Jacobs, M.; Dijkstra, J.; van Laar, H.; Cant, J.; Tulpan, D.; Ferguson, N. Synergy between mechanistic modelling and data-driven models for modern animal production systems in the era of big data. Animal 2020, 14, s223–s237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poteko, J.; Zähner, M.; Schrade, S. Effects of housing system, floor type and temperature on ammonia and methane emissions from dairy farming: A meta-analysis. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 182, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaliano, S.; D’urso, P.R.; Arcidiacono, C.; Cascone, G. Ammonia Emissions and Building-Related Mitigation Strategies in Dairy Barns: A Review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis, E.; Calvet, S.; Del Prado, A.; Estellés, F. A meta-analysis of environmental factor effects on ammonia emissions from dairy cattle houses. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 178, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.-Q.; Heber, A.J.; Sutton, A.L.; Kelly, D.T. Mechanisms of gas releases from swine wastes. ASABE 2009, 52, 2013–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borhan, M.S.; Khanaum, M.M. Sensors and Methods for Measuring Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Different Components of Livestock Production Facilities. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2022, 10, 242–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Methane Emissions in Livestock and Rice Systems—Sources, Quantification, Mitigation and Metrics 2023; United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- D’URso, P.R.; Arcidiacono, C.; Valenti, F.; Janke, D.; Cascone, G. Measuring ammonia concentrations by an infrared photo-acoustic multi-gas analyser in an open dairy barn: Repetitions planning strategy. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 204, 107509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, C.; Ammon, C.; Berg, W.; Fiedler, M.; Loebsin, C.; Sanftleben, P.; Brunsch, R.; Amon, T. Seasonal and diel variations of ammonia and methane emissions from a naturally ventilated dairy building and the associated factors influencing emissions. Sci. Total. Environ. 2014, 468, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özesmi, S.L.; Tan, C.O.; Özesmi, U. Methodological issues in building, training, and testing artificial neural networks in ecological applications. Ecol. Model. 2006, 195, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craninx, M.; Fievez, V.; Vlaeminck, B.; De Baets, B. Artificial neural network models of the rumen fermentation pattern in dairy cattle. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2008, 60, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahinfar, S.; Mehrabani-Yeganeh, H.; Lucas, C.; Kalhor, A.; Kazemian, M.; Weigel, K.A. Prediction of breeding values for dairy cattle using artificial neural networks and neuro-fuzzy systems. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2012, 2012, 127130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, L.O.; Greenwood, P.L.; Halachmi, I. Advancements in sensor technology and decision support intelligent tools to assist smart livestock farming. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99, skab038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Sharma, S.K. Advanced contribution of IoT in agricultural production for the development of smart livestock environments. Internet Things 2023, 22, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, C.; Mancino, M.; Porto, S.M.C.; Cascone, G.; Bloch, V.; Pastell, M. The COWBHAVE System: An Open-Source Accelerometer-Based System to Monitor Dairy Cows’ Behavioural Activities. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Safety, Health and Welfare in Agriculture and Agro-Food Systems, Ragusa, Italy, 15–18 September 2021; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, C.; D’Emilio, A. CFD analysis as a tool to improve air motion knowledge in dairy houses. Riv. Ing. Agrar. 2006, 37, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, N.; Valenti, F.; Cascone, G.; Porto, S.M.C. Development of a CFD model to simulate natural ventilation in a semi-open free-stall barn for dairy cows. Buildings 2019, 9, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bournet, P.-E.; Rojano, F. Advances of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) applications in agricultural building modelling: Research, applications and challenges. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 201, 107277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mulder, T.; Peiren, N.; Vandaele, L.; Ruttink, T.; De Campeneere, S.; Van de Wiele, T.; Goossens, K. Impact of breed on the rumen microbial community composition and methane emission of Holstein Friesian and Belgian Blue heifers. Livest. Sci. 2018, 207, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.; Yin, T.; Reichenbach, M.; Bhatta, R.; Malik, P.K.; Schlecht, E.; König, S. Enteric methane emissions of dairy cattle considering breed composition, pasture management, housing conditions and feeding characteristics along a rural-urban gradient in a rising megacity. Agriculture 2020, 10, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asman, W.A. Ammonia emission in Europa: Updated emission and emission variations. 1992. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10029/258542.

- Moran, D.; Wall, E. Livestock production and greenhouse gas emissions: Defining the problem and specifying solutions. Anim. Front. 2011, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdos, J.I.; Ncho, C.M.; Son, A.-R.; Lee, S.-S.; Kim, S.-H. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emission estimation for cattle: Assessing the potential role of real-time feed intake monitoring. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, S.; Linden, N.; Kennedy, A.; Knight, M.; Paganoni, B.; Kearney, G.; Thompson, A.; Behrendt, R. Correlations between feed intake, residual feed intake and methane emissions in Maternal Composite ewes at post weaning, hogget and adult ages. Small Rumin. Res. 2020, 192, 106241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samer, M. GHG emission from livestock manure and its mitigation strategies. In Climate Change Impact on Livestock: Adaptation and Mitigation; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Li, Q.; Zhao, C.; Wang, C.; Yan, H.; Meng, R.; Liu, Y.; Yu, L. TGFN–SD: A text-guided multimodal fusion network for swine disease diagnosis. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2025, 15, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, C.; Borgonovo, F.; Gardoni, D.; Guarino, M. Comparison among NH3 and GHGs emissive patterns from different housing solutions of dairy farms. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 141, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastomo, W.; Aini, N.; Karno, A.S.B.; Rere, L.R. Machine learning methods for predicting manure management emissions. J. Nas. Tek. Elektro Dan Teknol. Inf. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors [Citation] | Year | Title | Time Period of the Articles Analysed | Number of Selected Articles | Aim or Focus | Review Methodology | Livestock Analysed | Type of Livestock Management | Gas Analysed | Instruments and Devices for Data Gathering | ML and ANN Models Applied | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shine and Murphy [42] | 2021 | Over 20 years of Machine Learning Applications on Dairy Farms: A Comprehensive Mapping Study | 1999–2021 | 129 | Six research questions: (1) What countries/regions are responsible for the largest number of publications? (2) What journal and conference proceedings are research publications being published in? (3) What problem areas are being addressed using ML in the dairy farming domain? (4) What features are being applied to develop ML modes? (5) What ML algorithms are being utilised to develop the models? (6) Which evaluation metrics and methods are used? | Systematic mapping review | Dairy Cattle | Farm (Housing, Grazing, Pasture) | CH4 | Undefined | ML: Bayes—Naive Bayes, Bayes net; Meta—Bagging, Adaboost; Rule—OneR; Statistical Regression—Logistic Regression, MLR, PLS, Linear Discriminant Analysis, Linear Regression, GAM; Tree—RF, Decision Tree, Gradient Boosting Machine, C4.5, CART, XGBoost; ANN: MLP, CNN, RNN | RQ3 Calving (Pregnancy, Conception Rate, Abortion, Reproduction Performance) Information = 23%; Cow Characteristics (Age, Weight, Breed, Genetics, Body Parameters, Medical Conditions) = 34%; Lactation Information = 19%; Milk Characteristics = 37%; Sensors = 48%; Soil Characteristics = 1%; Diet and Feeding = 11%; Milking Parameters = 10%; Meteorological Conditions = 14%; Other Variables = 7%; Farm Characteristics (Herd Size, Cooling System, Housing, Water Energy, Energy Balance, Ventilation) = 16%; RQ3: Physiology and Health = 27; Behaviour Analysis = 24; Accelerometer = 27; Image = 7; Pedometer = 6; RQ4: Tree-based Algorithms = 54%; ANN Algorithms = 50%; Statistical Regression-based Algorithms = 43%; Other types = 37%; Bayes Algorithms = 17%; Meta = 10%; Rule = 4%; Clustering = 1%; RQ6: RMSE = 56%; R2 = 46%; r = 27%; MAE = 24%; CCC = 17%; MAPE = 15%; MSE = 15%; RPE = 15%; MPE = 10%; MSPE = 7% |

| Rahman et al. [43] | 2022 | Prospect and scope of artificial neural network in livestock farming: a review | Undefined; From Table 1 emerged a timeframe from 2008 to 2022 | Undefined; From Table 1 emerged a selection of 20 papers | Discover the potential implications of ANN in the different fields of animal science | Narrative review | Dairy Cattle, Beef Cattle, Buffalo, Sheep, Goat, Swine | Farm, Pasture | CH4, CO2, total gas emission | Undefined | CNN, RNN, Bayes NN, MLP | RQ3: ANN models can be applied in several livestock contexts, such as animal breeding, prediction of milk yield, evaluation of meat animals, inferring demography and recombination, genome-enabled prediction, animal nutrition, animal health and reproduction management, and in animal management in developing countries. |

| Bresolin and Dórea [46] | 2020 | Infrared Spectrometry as a High-Throughput Phenotyping Technology to Predict Complex Traits in Livestock Systems | Undefined; Authors specified that research ended in May 2020 | 113 | Provide recent updates in MIR and NIR technologies and review analytical methods for spectral data analysis to improve predictive ability, different approaches to reduce data dimensionality, and impact of validation strategies on prediction | Systematic review | Dairy and Beef Cattle | Farm | CH4 | Respiration chamber, sulphur hexafluoride tracer, and sniffer systems | PLS, Principal component regression, Bayes B, SVM, undefined ANN models | RQ6: R2 of ML methods (MLS, Bayes B) for CH4 emission ranged from 0.0 to 0.79 |

| Jiang et al. [49] | 2020 | Analysis of Strategic Emission-Based Energy Policies of Developing and Developed Economies with Twin Prediction Model | 1981–2012 | 23 | Forecast CH4 emission and agricultural output (grown rate) by using Box–Jenkins and ANN methods and assess sustainability of CH4 emission vs. agricultural output | Systematic review | Undefined | Undefined | CH4, CO2, N2O, Green House Gases | Undefined | Statistical Box–Jenkins and Nonlinear autoregressive neural network (NAR) methods | RQ5: All applied methods have shown an increase in emission from non-OCSE countries (+30%), while OCSE countries are reducing their emission (−17.35%). Agricultural output trend is increasing for all countries (+62%) |

| Niloofar et al. [53] | 2021 | Data-driven decision support in livestock farming for improved animal health, welfare and greenhouse gas emissions: Overview and challenges | Undefined | Undefined | Provide an overview of the existing data-driven approaches in PLF and categorise them according to the different goals they aim for | Undefined | Cattle, Swine, Poultry | Farm | CH4, CO2, NH3, Green House Gases, N2O | Undefined | ML: KNN, SVM, Gaussian Mixture Models, Bayesian Network, RF; ANN: CNN, ANFIS, Undefined | RQ5: IPCC methodology lacks optimisation approaches to estimate GHG emission, but the ANNs’ estimation is accurate. Authors suggested applying several methods adapted to each farm to maximise the outputs |

| No. | Authors | Years | Time Span | Study Area | Preprocessing | Neural Network | Validation Criteria | Training Algorithm | Software | Focus and Aims | Livestock/Source of Gas | Analysed Gas and Devices | Variables Analysed | Area of Research (Laboratory–Housing–Field) | Type of Gas Measurement/Most Significant Parameters | Type of ANN Approach | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kolasa-Więcek [61] | 2013 | 20 years | Poland | Undefined | Multilayer Perceptron | R2 | Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno | Statistica®—TIBCO Software | ANN model to assess N2O from direct soil emissions in relation to the use of crops and livestock population; Evaluate the most representative variables in the ANN model tested | Cattle; Horses; Poultry; Sheep; Swine; Goats | N2O obtained from undefined devices | (1) Input—arable land, permanent crop and pastures, livestock population output—direct N2O emissions (2) Input—wheat, barley, triticale, rye, maize, sugar beet, rapeseed, oats, potatoes, permanent meadows and pasture, livestock population × output—direct soil emissions | Open field | Emissions estimated in CO2 equivalent | Comparison of ANN hundreds of models: MLP 9–4–1 and MLP 16–5–1 reported as the best | MLP 16–5–1 = 98% Variables Sensitivity: Cattle 8.83, Swine 8.55, Rapeseed 7.05, Rye 6.09, Oats 4.95, Permanent meadow and pasture 4.65, Horses 4.06, Potatoes 3.53, Sheep 3.35, Mize 2.85, Wheat 2.46, Goats 2.38, Sugar beet 2.33, Poultry 2.21, Barley 1.95, Triticale 1.90 |

| 2 | Martinez et al. [62] | 2021 | 47 days | France | L2 Normalisation | Multilayer Perceptron | RMSE | Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno | Python® | Evaluate sensitivity of Figaro® resistances to CH4 versus the variables selected, combining low-cost devices with cross sensitivity variables to assess CH4 concentration and its variability | Manure | CH4 from tin-oxide Figaro® resistances | CO2, water vapour, pressure, and temperature | Laboratory facility under controlled conditions | Concentrations expressed in ppm | Comparison of ANN models: only MLP 14–19 reported | MLP 14–19 = RMSE <0.2 Water vapour is the most important variable while CO have to be omitted to improve performance. However, Figaro® resistances proved to be highly dependent for value of CO < 0.15 ppm and temperature < 26.5 °C |

| 3 | Lovanh et al. [63] | 2014 | 1 month | USA | Variables selected with K-predictors in Statistica®—TIBCO Software | Multilayer Perceptron | MAE, MSE, SD | Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno | Statistica®—TIBCO Software | Evaluate the effect of heat fluxes in NH3 emissions from waste lagoon | Swine | NH3 from INNOVA 1412 device | Surface temp, temp at 0.5 m, temp at 1.5 m, pH, moisture, pressure, wind speed and relative humidity | Farrowing pig farm | Emissions expressed in ppm | Comparison of ANN models: MLP 5–13–1, MLP 5–6–1, MLP 5–7–1, and MLP 5–15–1 | MLP 5–7–1: MAE 0.018, MSE 0.001 and SD 0.031 |

| 4 | Sun et al. [64] | 2008 | 15 months | USA | PCA applied | Radial Basis Function Network | RMSE, MAE, R2 | Undefined | MATLAB | Develop ANN model to predict air pollutant affected by the variables selected from piggeries | Swine | NH3 measured with chemiluminescence device, CO2 obtained from photoacoustic infrared analyser, PM10 obtained from tapered element oscillating microbalance, and H2S obtained from pulsed fluorescence sulphur device | Time of the day, season, ventilation rate, animal growth cycle, manure storage level, and weather conditions | Deep pit piggeries | Emissions expressed in Animal Unit and Concentrations expressed in ppm | Comparison of ANN models: Models were undefined | CO2 concentration model: R2 = 0.99; CO2 emission model: 0.93; H2S emission model: 0.92; NH3 concentration model: 0.91; NH3 emission, PM10 emission, and H2S concentration models between 0.88 and 0.81. MAE and RMSE undefined but reported as low by the authors |

| 5 | Lim et al. [65] | 2007 | 3 years | Republic of Korea | PCA applied | Novel Piecewise-affine Network | MSE, R2 | Backpropagation | MATLAB | Create a method to predict NH3 emissions and identify relative significance NH3 emissions factors | Field-applied manure | NH3 obtained from ALFAM database | Soil types, weather, manure characteristics, agronomic factors, and measuring techniques | Open field | Most important emissions factors: Wind speed, soil pH, average air temperature, and manure pH | Comparison of ANN (PWA-26) and statistical models (MLR) | PWA: Km = R2 0.99; Nmax: R2 0.99; MLR: Km = R2 0.37; Nmax: R2 0.66 |

| 6 | Hempel et al. [66] | 2019 | 2 years | Germany, Spain | Undefined | Multilayer Perceptron | R2 | Backpropagation | Python® | Evaluate heat stress risks in dairy cattle applying ANN, ML and statistical models | Dairy Cattle | NH3 and CH4, obtained indirectly from environmental variables and heat stress | Temperature, relative humidity, zonal and meridional wind, sea level pressure, and global radiation | Dairy cattle farms | Emissions expressed in CO2 equivalent | Comparison of ANN (MLP up to 3 hidden layers; neurons were undefined), ML (RF, SVM) and statistical (LR) models | MLP: Dummerstorf = R2 0.74; Groß Kreuz = R2 0.56; Bétera = R2 0.85; ML and statistical = undefined; Increasing of 2.9% (550 Gg) in Germany and 4.5% (353 Gg) in Spain |

| 7 | Hempel et al. [67] | 2020 | 10 months | Germany | Undefined | Multilayer Perceptron | RMSE, MAE, TAE, R2 | Backpropagation | Python® | ML models can best prediction NH3 emissions compared to statistical models; estimating the minimal temporal requirements for temporal sampling of training data; provide cons and pros of different ML approaches compared to ordinary statistical approaches | Dairy Cattle | NH3 obtained from Fourier Transform Infrared spectrometers | Hourly emission values derived from ventilation rate, time, temperature, wind speed and direction | Dairy cattle farms | Emissions expressed in Livestock Unit | Comparison of ANN (MLP: undefined), ML (SVM, XGBoost) and statistical (LR, RR) models | 27 scenarios tested: best was 7th = MAE 0.480, RMSE 0.418, R2 0.088; 13th = TAE 0.146 |

| 8 | He et al. [68] | 2023 | 21 years | China | Undefined | Backpropagation Neural Network | R2 | Backpropagation | MATLAB | Accurate mathematical models to estimate emission from livestock excreta | Cattle, sheep, pigs, poultry, horses, donkey, mules, camels, and rabbit | Direct emission from fresh and dry excreta from undefined devices | Excreta rate, rearing cycle, moisture content, and commercial scale husbandry coefficient | Region of China | Emissions express in Unit (Mt/Year) of Dry and Fresh excreta | Comparison of ANN (undefined, Backpropagation Neural Network) and statistical (ARIMA) models | 4 ANN model tested: Fresh manure = 0.93 RMSE; Dry Manure = 0.95 RMSE; Fresh manure from commercial-scale feedlot = 0.95 RMSE; Dry manure from commercial-scale feedlot = 0.98 RMSE; ARIMA: Fresh manure = 8.35 RMSE; Dry Manure = 7.20 RMSE; Fresh manure from commercial-scale feedlot = 7.30 RMSE; Dry manure from commercial-scale feedlot = 6.89 RMSE |

| 9 | Küçüktopcu and Cemek [69] | 2021 | NA | Turkey | Normalisation (Min–Max) | Multilayer Perceptron | SEP, RSR, AAPRE, R2, RMSE | Levenberg–Marquardt, Bayesian Regularisation, Scaled Conjugate Gradient | MATLAB | ANN model to assess CO2 emission, insulation thickness, and energy saving | Poultry | Mitigation of CO2 emissions from undefined devices | Annual total savings, heating degree days, optimum insulation thickness, reduction of CO2, total wall heat resistance, insulation materials, fuels, interest rate, and building lifetime | Poultry farm | Emissions expressed in Total CO2/Year | Comparison of ANN (MLP: 1 hidden layer with 8 to 15 neurons) and different training algorithms (LM, BR, and SCG) | 3 ANN models (optimum insulation thickness, annual total net saving, and reduction of CO2 emission) evaluated for each training algorithms: OIT LM = 0.99 R2, 0.01 RMSE, 2.60 SEP, 0.03 RSR, 2.72 AAPRE;OIT BR = 0.99 R2, 0.01 RMSE, 3.70 SEP, 0.05 RSR, 3.44 AAPRE; OIT SCG = 0.99 R2, 0.01 RMSE, 4.22 SEP, 0.06 RSR, 10.87 AAPRE; ATS LM = 0.99 R2, 0.94 RMSE, 5.58 SEP, 0.04 RSR, 8.18 AAPRE;ATS BR = 0.99 R2, 1.70 RMSE, 10.15 SEP, 0.07 RSR, 10.47 AAPRE; ATS SCG = 0.99 R2, 1.97 RMSE, 11.79 SEP, 0.89 RSR, 14.34 AAPRE; RCO2 LM = 0.99 R2, 1.04 RMSE, 1.72 SEP, 0.05 RSR, 4.17 AAPRE;RCO2 BR = 0.99 R2, 1.62 RMSE, 2.67 SEP, 0.08 RSR, 6.47 AAPRE; RCO2 SCG = 0.99 R2,1.98 RMSE,3.26 SEP, 0.09 RSR, 10.86 AAPRE |

| 10 | Basak et al. [70] | 2022 | 3 months | Republic of Korea | Z-score Normalisation | Backpropagation Network | RMSE, R2 | Backpropagation | Python® | Modelling CH4 manure emission using statistical and machine learning methods | Swine | CH4 obtained from IPCC tier 2 equation approach | Mass of pigs, age, and feed intake | Piggeries | Emissions expressed in Pig/kg×*Year | Comparison of ANN (BPNN: undefined), ML (RF) and statistical (MLR, PL, RR) models | Best value of models: MLR = R2 0.90, RMSE 0.01; PR = R2 0.91, RMSE 0.01; RR = R2 0.92, RMSE 0.01; RF = R2 0.97, RMSE 0.01; ANN = R2 0.90, RMSE 0.01 |

| 11 | Park et al. [71] | 2023 | 10 months | Republic of Korea | Sliding window | Recurrent Neural Network, Convolutional Neural Network, Transformer Neural Network | MAE | Undefined | NA | Comparative analysis of ANN models to predict NH3 concentrations | Swine | NH3 measured with INNOVA 1512i | Ventilation rate, temperature, RH, and NH3 | Gestation pig facilities | Concentrations expressed in ppm | Comparison of ANN (MLP = undefined; RNN = 3 hidden layers with 64 neurons; CNN = 1D; Transformer = undefined) models | Input = 1 week, output = 1 week: (MLP = 2.15 MAE, RNN = 1.83 MAE, CNN = 2.02 MAE, Transformer = 1.89 MAE); input = 1 week, output = 2 week: (MLP = 2.24 MAE, RNN = 1.78 MAE, CNN = 1.92 MAE, Transformer = 1.90 MAE); input = 1 week, output = 3 week: (MLP = 2.20 MAE, RNN = 1.95 MAE, CNN = 1.89 MAE, Transformer = 1.87 MAE); input = 1 week, output = 4 week: (MLP = 2.15 MAE, RNN = 1.79 MAE, CNN = 1.87 MAE, Transformer = 1.73 MAE) |

| 12 | Genedy et al. [72] | 2023 | 3 years and 2 months | USA, Switzerland | Undefined | Recurrent Neural Network | RMSE, MAE | Undefined | Python® | Modelling ANN structure to assess NH3 from manure storage | Dairy Cattle | NH3 obtained from tuneable diode laser spectrometer | Animal numbers, air temperature, wind speed and direction, manure temperature, and pH | Dairy cattle farms | Emissions expressed in g×m2/d | Comparison of ANN (undefined—PI–LSTM, HT–CPBM, and Base–CPBM) models | 2 datasets applied—flushed lagoon (Base–CPBM = 2.19 MAE, 3.34 RMSE, HT–CPBM = MAE 1.40, RMSE 2.38, and PI–LSTM = 1.23 MAE, 2.20 RSME); steel tank (Base–CPBM = 1.29 MAE, 2.42 RMSE, HT–CPBM = MAE 1.26, RMSE 2.39, and PI–LSTM = 0.97 MAE, 1.64 RSME) |

| 13 | Chen et al. [60] | 2022 | 26 years | UK | Normalisation (Min–Max) | Feedforward Network | R2, RMSE, Concordance Correlation Coefficient | Backpropagation | R | Comparing statistical and ML models to predict nitrogen excretion from manure | Dairy Cattle | Nitrogen excretion | Nitrogen intake, dietary Nitrogen intake, milk yield, dietary forage proportion, live weight, and diet metabolizable energy content | Dairy cattle farms | Nitrogen excretion | Comparison of ANN (FNN: from 1 to 3 hidden layer, and from 1 to 6), ML (RF, SVM) and statistical (MLR) models | MLR = 44.7 RMSE, 0.60 CCC; RF = 46.8 RMSE, CCC 0.58; SVM = 44.9 RMSE, CCC 45.3; ANN 34.7 RMSE, CCC 0.70 |

| 14 | Besteiro et al. [73] | 2017 | 78 days | Spain | Bayesian Information Criterion | Feedforward Network | RMSE | Backpropagation | R | Modelling ANN structure to assess CO2 from piglet facilities | Swine | CO2 obtained from Delta Ohm HD37BTV.1 transmitter | CO2 concentration in animal zone, Variation of CO2 concentration in animal zone, and external temperature | Piggeries | Concentrations expressed in ppm | Comparison of ANN (undefined) models | ANN = 26.33 RMSE, 1.26% MARE, 0.99 r, and 0.99 IA |

| 15 | Shi et al. [74] | 2024 | 1 day | China | Normalisation (Min–Max) | Recurrent Neural Network, Backpropagation Neural Network, Particle Swarm-Optimised Backpropagation Neural Network | R2, MAE, RMSE | Backpropagation | NA | Combining electric nose in bionic chamber with ANN model to detect NH3 emissions | Livestock excreta | NH3 and Ethanol obtained from SMD1002 and SMD1005 sensors installed in National Instrument USB6289 (Emerson Electric Co., St. Louis, USA) with 10 Hz frequency | Different concentrations of NH3 and Ethanol, collected with different sensors | Laboratory facility under controlled conditions | Emissions expressed in ppm | Comparison of ANN (undefined—RNN, BPNN, and PSO-BPNN) models | All ANN structures were undefined—BP = NH3 0.99 R2, 5.67 MAE, 8.10 RMSE; Ethanol 0.99 R2, 2.38 MAE, 3.04 RMSE; RNN = NH3 0.96 R2, 9.47 MAE, 17,97 RMSE; Ethanol 0.99 R2, 4.78 MAE, 6.04 RMSE; PSO-BP = NH3 0.96, 0.23 MAE, 16.67 RMSE; Ethanol 0.99 R2, 3.56 MAE, 5.33 RMSE |

| 16 | Stamenković et al. [75] | 2015 | 8 years | 20 European countries 1 | Undefined | General Regression Neural Network, Backpropagation Network | MAE, RMSE, Index of Agreement, Pearson Correlation Coefficient | Backpropagation | NA for ANN; IBM SPSS Statistic for Windows for MLR | Modelling ANN to estimate CH4 emission | Cattle | CH4 obtained from EDGAR database | Gross domestic product, waste deposit, municipal waste generation, land use, number of cattle, primary production of gas, and CH4 emissions | Country based | Emissions expressed in kg per capita | Comparison of ANN (undefined—BPNN, GRNN) and statistical (MLR) models | BPNN = 1.00 IA, 3.4 MAE, 5.0 RMSE, 0.97 r; GRNN = 0.97 IA, 3.6 MAE, 7.0 RMSE, 0.94 r; MLR = 0.83 IA, 11.3 MAE, 14 RMSE, 0.75 r |

| 17 | Shadpour et al. [76] | 2022 | 5 years | Canada, Denmark | Normalisation (Min–Max) | Multilayer Perceptron (LMANN, BRANN, SCGANN) | RMSE, Pearson Correlation Coefficient, Residual Prediction Deviation | Levenberg–Marquardt, Bayesian Regularisation, Scaled Conjugate Gradient | MATLAB | Predicting CH4 emission from common device with ANN models | Dairy Cattle | CH4 obtained from Mid-Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy | Age at calving, milk yield, fat yield, protein yield, and mid-infrared spectroscopy | Dairy cattle farms | Emissions expressed as weekly average | Comparison of ANN (LMANN, BRANN, SCGANN all with 1 hidden layer) and statistical (PLS, models | PLS = 0.255 PCC, 90.45 RMSE, 1.21 RPD; LMANN = 0.360 PCC, 93.32 RMSE, 1.10 RPD; BRANN = 0.320 PCC, 95.21 RMSE, 1.08 RPD; SCGANN = 0.330 PCC, 97.20 RMSE, 1.06 RPD |

| 18 | Peng et al. [77] | 2022 | 1 month | China | Normalisation (Min–Max) | Recurrent Neural Network, Backpropagation Neural Network | MAE, RMSE, R2 | Backpropagation | Python® | PredictingNH3 from piggeries applying ANN and ML approaches | Swine | NH3 obtained from INNOVA 1412i | NH3, CO2, H2O, pressure, outdoor temperature, indoor ventilation, indoor temperature, indoor humidity, and outdoor rainfall | Piggeries | Concentrations expressed in ppm | Comparison of ANN (undefined—BPNN, RNN, PSO-BPNN, PSO-RNN) and ML (SVM, XGBoost) models | RNN = 0.92 R2; BPNN = 0.80 R2; SVM = 0.89 R2; XGBoost = 0.92 R2; PSO-RNN = 0.96 R2, 0.61 RMSE |

| Articles | Emission | Concentrations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation Method | Tracer Gas | Measurement Methodologies | Measurement Duration | Devices | Frequency of Measurement | Calibration | Measurement Location | |

| Kolasa-Więcek [61] | CO2 equivalent | N.A. | Data Obtained from FAO, Ifa, and UNFCCC Databases | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | |

| Martinez et al. [62] | N.A. | N.A. | Gas sensing through voltage measuring | 47 days | Figaro TGS (2600, 2611-C00, 2611-E00), Sensirion SHT75, Bosch BMP180 | 5 min | Yes | N.A. |

| Lovanh et al. [63] | Mass balance | N.A. | Photoacoustic Gas Analyzer | 1 month | Innova 1412, HOBO weather station, | 70 s | Yes | 0.5 m above lagoon |

| Sun et al. [64] | Mass balance | N.A. | Chemiluminescence, Photoacoustic Infrared, Tapered Element Oscillating Microbalance | N.A. | Model 17C Thermal Environment Instruments, Model 45C Thermal Environment Instruments | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Lim et al. [65] | Mass balance | N.A. | Data Obtained from Database (ALFAM, DIAS, IMAG, IGER, ADAS, CRPA) | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Hempel et al. [66] | CO2 equivalent | N.A. | Environmental Data from Database (DWD, NCDC, NOAA) | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | Yes | 3, 4, 6 m from floor |

| Hempel et al. [67] | Mass balance | N.A. | Infrared Spectrometry | 10 months | Gasmet (CX4000) | 10 min | Yes | 3.2, 4, 6 m from floor |

| He et al. [68] | Mass balance | N.A. | Data Obtained from National Database (China’s Statistical Yearbooks) | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Küçüktopcu and Cemek [69] | Mass balance | N.A. | Data Obtained from Database | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Basak et al. [70] | Mass balance | N.A. | Weather Sensing, pH Meter, Electronic Mass Balance | 3 months | MetPRO, HP9010, FX-300iWP | 24 h | N.A. | N.A. |

| Park et al. [71] | N.A. | N.A. | Photoacoustic Gas Analyzer, Ventilation Measuring Device, Environmental Parameters | N.A. | Innova 1512i, VelociCalc Air Velocity Meter 9535, Undefined indoor sensors | N.A. | Yes | N.A. |

| Genedy et al. [72] | Mass balance | N.A. | Spectrometry Laser | 3 years and 2 months | GasFinder2 | 10 min | N.A. | 1 m below, 1, 2, 3 m above tank storage |

| Chen et al. [60] | N.A. | N.A. | Data Obtained from Previous Studies | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Besteiro et al. [73] | N.A. | N.A. | Weather Sensing, Gas Sensing | 78 days | HOBO, Delta Ohm HD37BTV.1 | 10 min | N.A. | 0.2 m above separation slats |

| Shi et al. [74] | Mass balance | N.A. | Experimental Electronic Nose | 1 day | USB6289, LZB-4WB, SMD 1002, SMD 1005 | 3 min | Yes | N.A. |

| Stamenković et al. [75] | Mass balance | N.A. | Data Obtained from Annual National Database | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Shadpour et al. [76] | Mass balance | N.A. | Infrared Spectrometry, Sniffer | N.A. | MilkoScan FT+ | N.A. | Yes | N.A. |

| Peng et al. [77] | N.A. | N.A. | Photoacoustic Gas Analyzer, Environmental Parameters | 1 month | Innova 1412i, HOBO | 3 min (gas), 5 min (environment) | N.A. | 1.7 m from floor |

| Articles | Species | Breed | Number of Animals | Housing System | Ventilation System | Feed Composition | Manure Parameters | Manure Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kolasa-Więcek [61] | Cattle, Horses, Poultry, Sheep, Swine, Goats | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Martinez et al. [62] | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Lovanh et al. [63] | Swine | N.A. | 2.000 | Indoor Farrowing Piggeries | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | Anaerobic Waste Lagoon |

| Sun et al. [64] | Swine | N.A. | 960 | Indoor Fattening Piggeries | Force Ventilated | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Lim et al. [65] | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | Dry matter, Total Ammoniacal Nitrogen, pH | N.A. |

| Hempel et al. [66] | Cattle | Holstein-Friesian | 606 | Indoor Cattle Barn | Naturally Ventilated | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Hempel et al. [67] | Cattle | Holstein-Friesian | 355 | Indoor Loose Cattle Barn | Naturally Ventilated | Soy, Oilseed Rape, Maize, Rye, Lupins | N.A. | N.A. |

| He et al. [68] | Cattle, Sheep, Swine, Poultry, Horses, Donkey, Mules, Camels, Rabbit | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | Excreta Rate, Moisture | N.A. |

| Küçüktopcu and Cemek [69] | Poultry | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Basak et al. [70] | Swine | Yorkshire | 18 | Indoor Piglet Barn | Force Ventilated | Crude Protein, Crude Fat, Crude Fibre, Crude Ash, Calcium, Phosphorus, Lysine, Digestible Crude Protein, Digestible Energy | pH, Moisture, Dry Matter, Ash, Volatile Solid Daily Excretion Rate | Roof Manure Collector |

| Park et al. [71] | Swine | N.A. | 464 | Indoor Farrowing Piggeries | Force Ventilated | Crude Protein, Crude Fat, Crude Fibre, Crude Ash, Calcium, Phosphorus, Lysine | N.A. | Roof Manure Collector |

| Genedy et al. [72] | Cattle | N.A. | 2.680 | Indoor Free-Stall Cattle Barn | Naturally Ventilated | N.A. | Temperature, pH | Waste Lagoon, Steel Tank |

| Chen et al. [60] | Cattle | Holstein-Friesian, Holstein crossbreed, Norwegian and Swedish Red | 951 | Indoor Free-Stall Cattle Barn | N.A. | Grass Silage, Fresh Grass, Maize Silage, Whole Crop Wheat Silage | N.A. | N.A. |

| Besteiro et al. [73] | Swine | Large White x Landrace | 800 | Indoor Piglet Barn | Force Ventilated | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Shi et al. [74] | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Stamenković et al. [75] | Cattle | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Shadpour et al. [76] | Cattle | Holstein-Friesian | 202 | Indoor Cattle Barn | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Peng et al. [77] | Swine | N.A. | 220 | Indoor Fattening Piggeries | Force Ventilated | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Validation Criteria | N. of Papers |

|---|---|

| AAPRE | 1 |

| CCC | 1 |

| IA | 1 |

| MAE | 7 |

| MSE | 2 |

| PCC | 1 |

| R2 | 10 |

| RMSE | 12 |

| RPD | 1 |

| RSR | 1 |

| SD | 1 |

| SEP | 1 |

| TAE | 1 |

| MARE | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Santoro, L.M.; D’Urso, P.R.; Arcidiacono, C.; Cascone, G.; Coco, S. Artificial Neural Networks for Predicting Emissions from the Livestock Sector: A Review. Animals 2026, 16, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010101

Santoro LM, D’Urso PR, Arcidiacono C, Cascone G, Coco S. Artificial Neural Networks for Predicting Emissions from the Livestock Sector: A Review. Animals. 2026; 16(1):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010101

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantoro, Luciano Manuel, Provvidenza Rita D’Urso, Claudia Arcidiacono, Giovanni Cascone, and Salvatore Coco. 2026. "Artificial Neural Networks for Predicting Emissions from the Livestock Sector: A Review" Animals 16, no. 1: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010101

APA StyleSantoro, L. M., D’Urso, P. R., Arcidiacono, C., Cascone, G., & Coco, S. (2026). Artificial Neural Networks for Predicting Emissions from the Livestock Sector: A Review. Animals, 16(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010101