Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Role of the FST Gene in Goose Muscle Development

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Sample Collection

2.2. Molecular Cloning of gFST cDNA

2.3. Tissue Expression Pattern Analysis of gFST mRNA

2.4. Goose SMSC Isolation, Purification and Expression Analysis

2.5. Overexpression Vector Construction, Cell Transduction, and FACS Analysis

2.6. RNA Extraction, Library Preparation and Transcriptome Analysis

2.7. Verification of DEGs by qRT-PCR

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

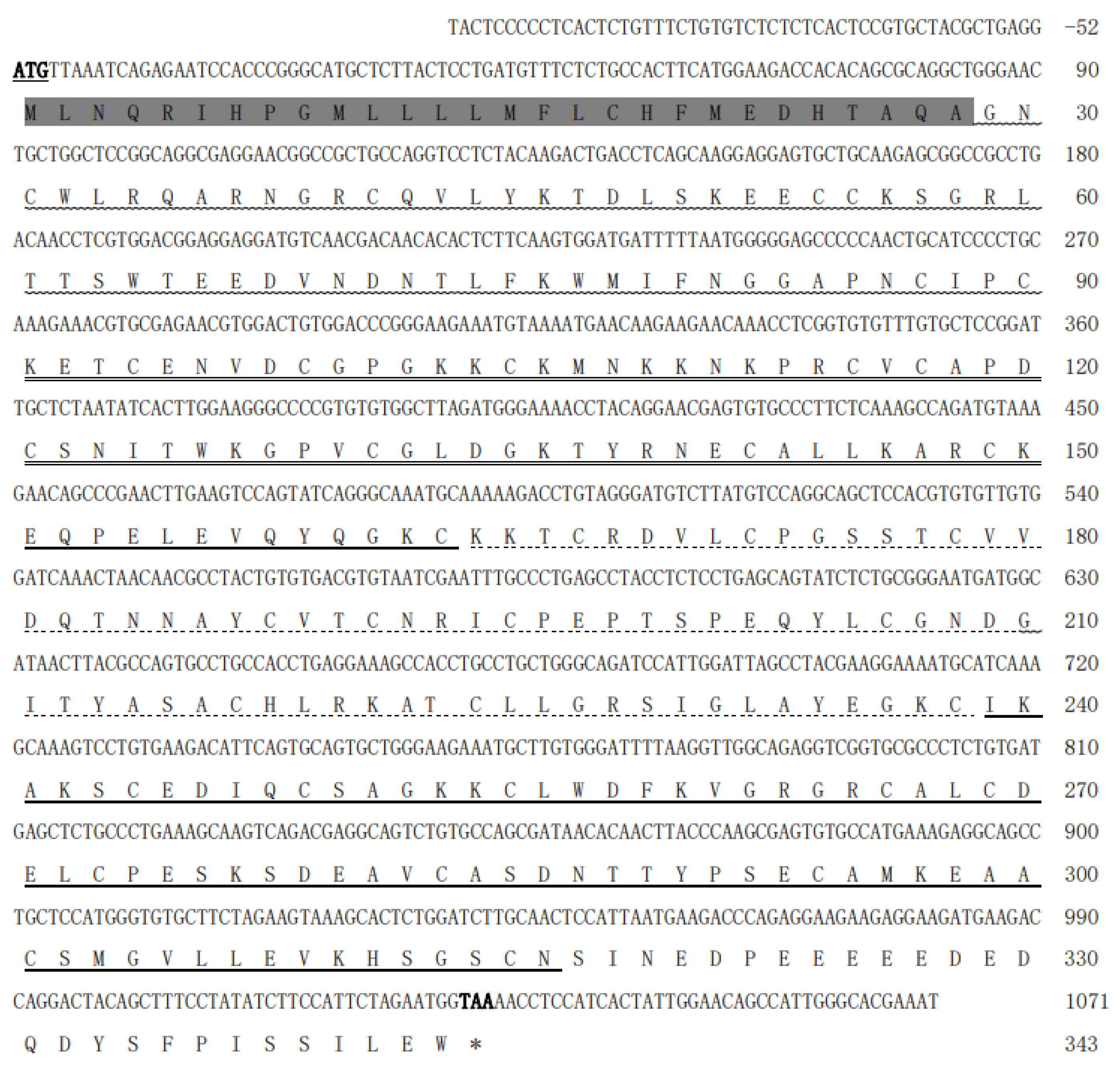

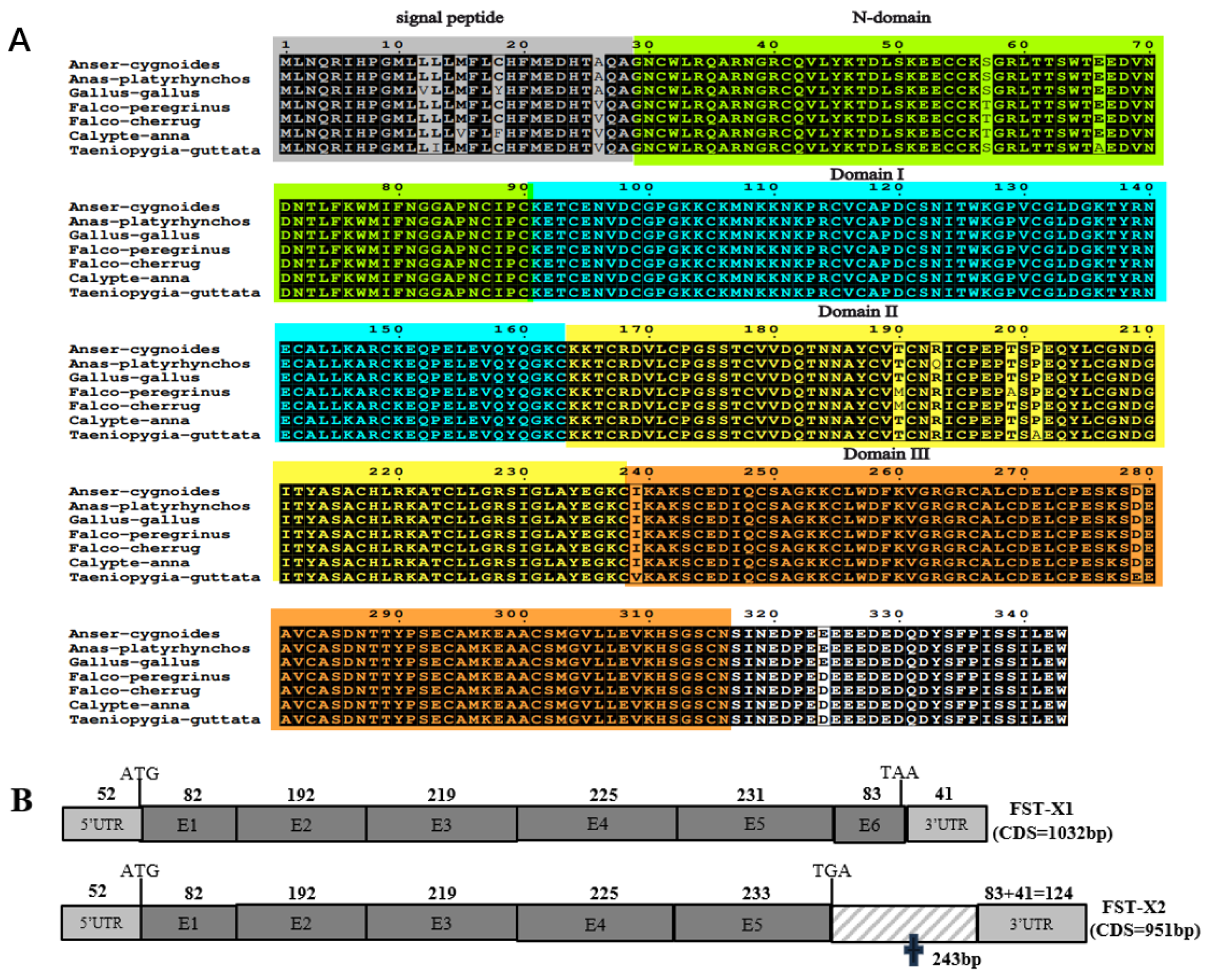

3.1. Molecular Characterization of gFST Gene

3.2. Tissue Expression Pattern of gFST mRNA

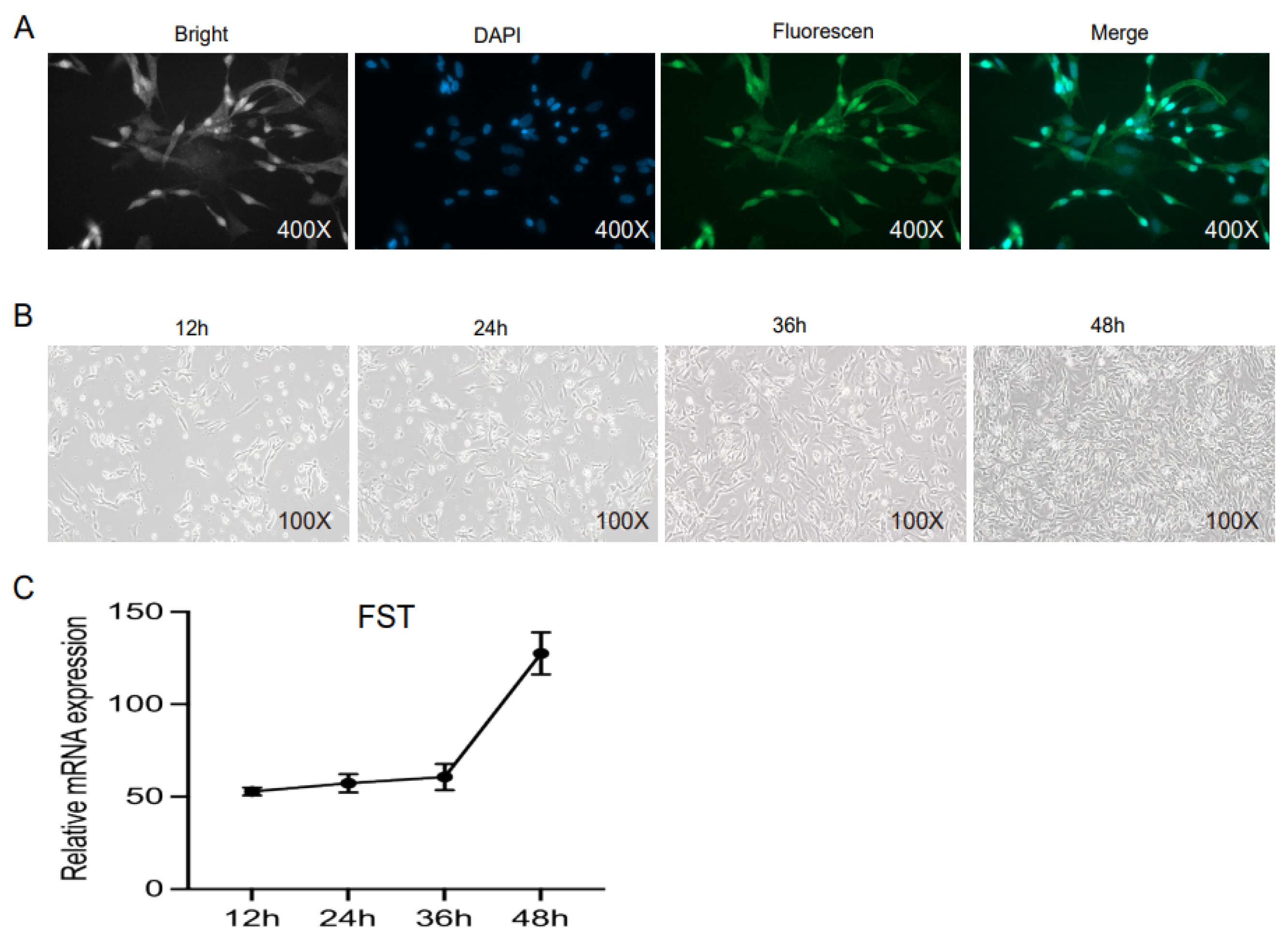

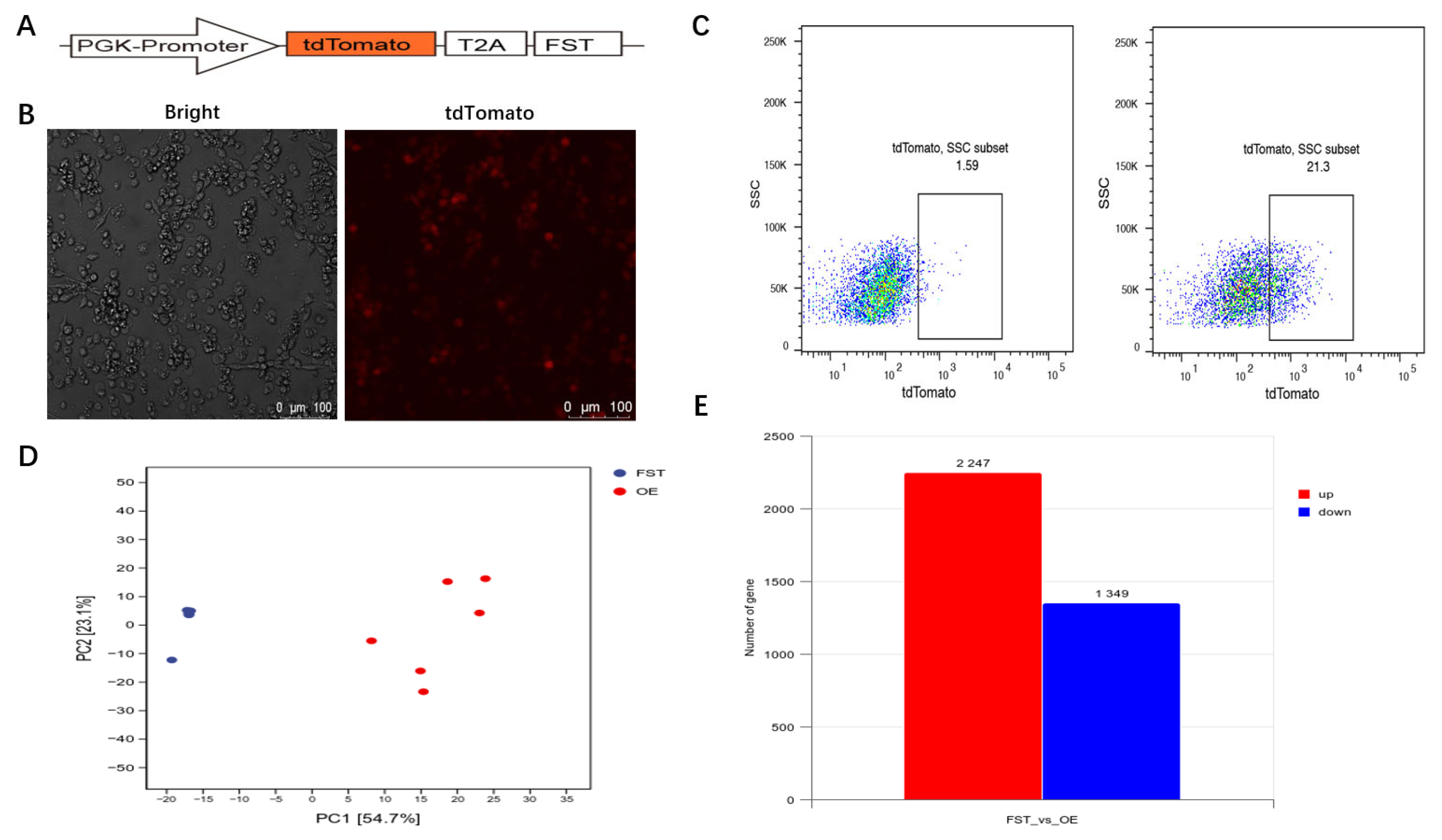

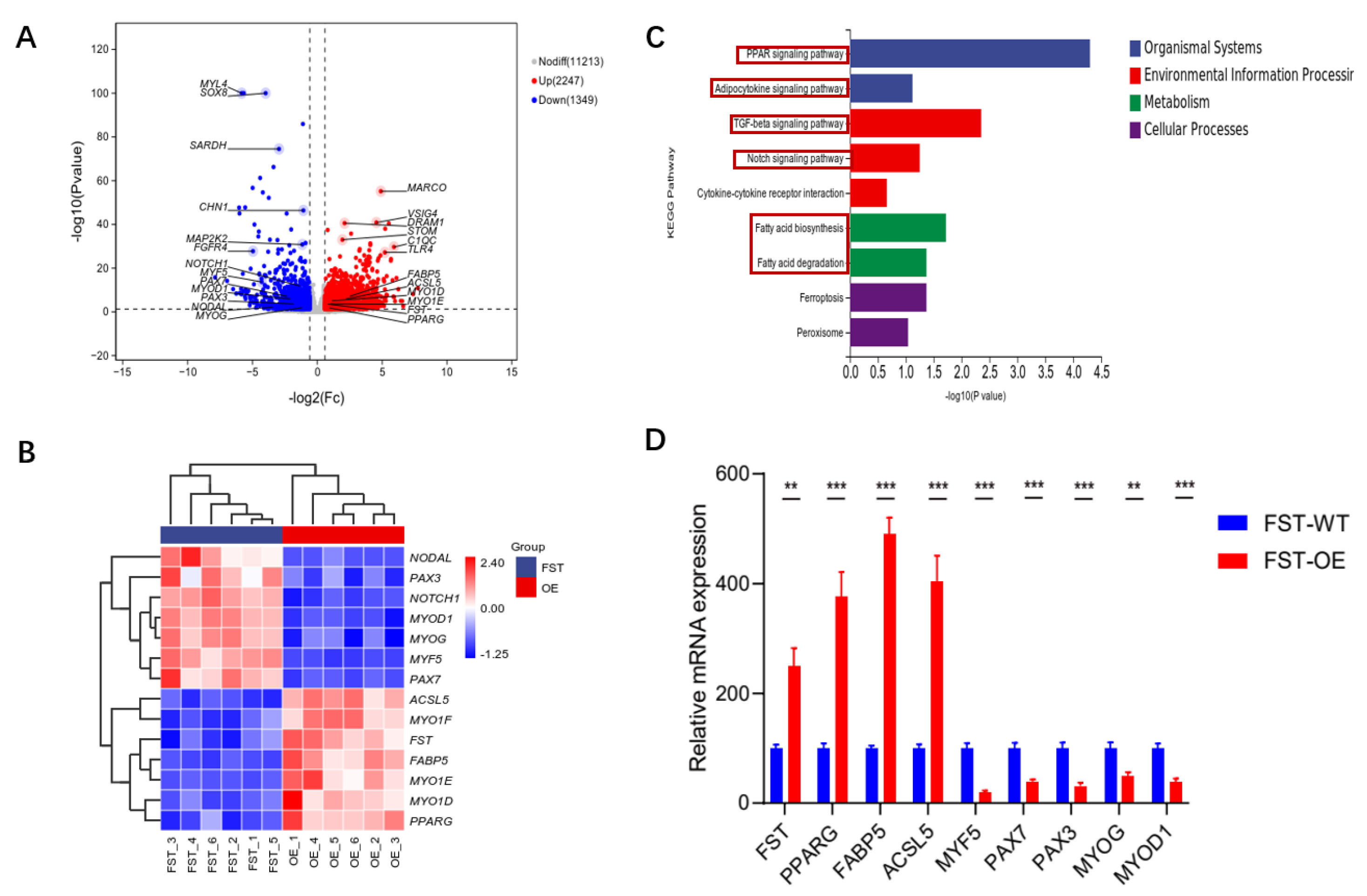

3.3. Gene Expression Analysis of FST-Overexpressed Cells

3.4. Identification of Key Genes Associated with SMSC Development

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sidis, Y.; Mukherjee, A.; Keutmann, H.; Delbaere, A.; Sadatsuki, M.; Schneyer, A. Biological activity of follistatin isoforms and follistatin-like-3 is dependent on differential cell surface binding and specificity for activin, myostatin, and bone morphogenetic proteins. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 3586–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervin, S.; Reddy, S.T.; Singh, R. Novel Roles of Follistatin/Myostatin in Transforming Growth Factor-β Signaling and Adipose Browning: Potential for Therapeutic Intervention in Obesity Related Metabolic Disorders. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 653179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J.; McPherron, A.C. Regulation of myostatin activity and muscle growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 9306–9311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, R.; Harasymowicz, N.S.; Wu, C.L.; Collins, K.H.; Choi, Y.R.; Oswald, S.J.; Guilak, F. Gene therapy for follistatin mitigates systemic metabolic inflammation and post-traumatic arthritis in high-fat diet-induced obesity. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz7492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ennequin, G.; Sirvent, P.; Whitham, M. Role of exercise-induced hepatokines in metabolic disorders. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 317, E11–E24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, R.; Fernández-Nocelos, S.; Carneiro, I.; Arce, V.M.; Devesa, J. Differential response to exogenous and endogenous myostatin in myoblasts suggests that myostatin acts as an autocrine factor in vivo. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 2795–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D.M.; Klein, R.; de Vos, F.L.; McLachlan, R.I.; Wettenhall, R.E.; Hearn, M.T.; Burger, H.G.; de Kretser, D.M. The isolation of polypeptides with FSH suppressing activity from bovine follicular fluid which are structurally different to inhibin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1987, 149, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, N.; Ling, N.; Ying, S.Y.; Esch, F.; Shimasaki, S.; Guillemin, R. Isolation and partial characterization of follistatin: A single-chain Mr 35,000 monomeric protein that inhibits the release of follicle-stimulating hormone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 8282–8286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.; Fang, R.; Wang, M.; Zhao, X.; Chang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Li, N.; Meng, Q. The transgenic expression of human follistatin-344 increases skeletal muscle mass in pigs. Transgenic Res. 2017, 26, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.W.; Chu, Y.K.; Zhang, W.J.; Qin, F.Y.; Xu, S.S.; Yang, H.; Rong, E.G.; Du, Z.Q.; Wang, S.Z.; Li, H.; et al. Polymorphisms of FST gene and their association with wool quality traits in Chinese Merino sheep. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.H.; Wang, J.W.; Yu, H.Y.; Zhang, R.P.; Chen, X.; Jin, H.B.; Dai, F.; Li, L.; Xu, F. Injection of duck recombinant follistatin fusion protein into duck muscle tissues stimulates satellite cell proliferation and muscle fiber hypertrophy. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 94, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, R.; Li, X.; Sun, L.; Wang, H.; Yang, C.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Xu, F. Influence of recombinant duck follistatin protein on embryonic muscle development and gene expressions. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2014, 98, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushyanth, K.; Shukla, R.; Chatterjee, R.N.; Bhattacharya, T.K. Expression and polymorphism of Follistatin (FST) gene and its association with growth traits in native and exotic chicken. Anim. Biotechnol. 2022, 33, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, J.; Li, J.; Yin, L.; Zhang, D.; Yu, C.; Du, H.; Jiang, X.; Yang, C.; Liu, Y. Comparative Analysis of Skeletal Muscle DNA Methylation and Transcriptome of the Chicken Embryo at Different Developmental Stages. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 697121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picard, B.; Lefaucheur, L.; Berri, C.; Duclos, M.J. Muscle fibre ontogenesis in farm animal species. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 2002, 42, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biressi, S.; Molinaro, M.; Cossu, G. Cellular heterogeneity during vertebrate skeletal muscle development. Dev. Biol. 2007, 308, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Zhao, X.L.; Yao, Y.G.; Liu, Y.P. Association of FATP1 gene polymorphisms with chicken carcass traits in Chinese meat-type quality chicken populations. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2010, 37, 3683–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Price, F.; Rudnicki, M.A. Satellite cells and the muscle stem cell niche. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 23–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halevy, O. Timing Is Everything-The High Sensitivity of Avian Satellite Cells to Thermal Conditions During Embryonic and Posthatch Periods. Front. Physiol. 2020, 31, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Yin, H.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, M.; Li, D.; Zhu, Q. PDLIM5 Affects Chicken Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cell Proliferation and Differentiation via the p38-MAPK Pathway. Animals 2021, 11, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, C.J.; Lee, E.Y.; Son, Y.M.; Hwang, Y.H.; Joo, S.T. Optimal Pre-Plating Method of Chicken Satellite Cells for Cultured Meat Production. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2022, 42, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, S.; He, D. Unveiling Key Genes and Crucial Pathways in Goose Muscle Satellite Cell Biology Through Integrated Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Liu, Z.; Cao, X.; He, H.; Han, S.; Chen, Y.; Cui, C.; Zhao, J.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.; et al. Circular RNA profiling identified an abundant circular RNA circTMTC1 that inhibits chicken skeletal muscle satellite cell differentiation by sponging miR-128-3p. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 15, 2265–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.; He, H.; Shen, X.; Zhao, J.; Cao, X.; Han, S.; Cui, C.; Chen, Y.; Wei, Y.; Xia, L.; et al. miR-9-5p Inhibits Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cell Proliferation and Differentiation by Targeting IGF2BP3 through the IGF2-PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1655. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Tang, S.; Du, F.; Li, H.; Shen, X.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xia, L.; Zhu, Q.; et al. miR-99a-5p Regulates the Proliferation and Differentiation of Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells by Targeting MTMR3 in Chicken. Genes 2020, 11, 369. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Ran, J.; Li, J.; Yu, C.; Cui, Z.; Amevor, F.K.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Qiu, M.; Du, H.; et al. miR-21-5p Regulates the Proliferation and Differentiation of Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells by Targeting KLF3 in Chicken. Genes 2021, 12, 814. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Xu, H.; Lu, Y.; He, Q.; Yan, C.; Zhao, X.; Tian, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, M.; et al. MUSTN1 is an indispensable factor in the proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis of skeletal muscle satellite cells in chicken. Exp. Cell. Res. 2021, 407, 112833. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, P.; Chen, M.; Li, J.; Lin, Z.; Yang, C.; Yu, C.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y. MYH1F promotes the proliferation and differentiation of chicken skeletal muscle satellite cells into myotubes. Anim. Biotechnol. 2023, 34, 3074–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISATgenotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, S.; Pyl, P.T.; Huber, W. HTSeq-a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2014, 31, 166–169. [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell, C.; Williams, B.A.; Pertea, G.; Mortazavi, A.; Kwan, G.; van Baren, M.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Wold, B.J.; Pachter, L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Feng, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. DEGseq: An R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNAseq data. Bioinformatics 2009, 26, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Gene Ontol. Consort. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.; Han, Y.; He, Q. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15545–51550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esch, F.S.; Shimasaki, S.; Mercado, M.; Cooksey, K.; Ling, N.; Ying, S.; Ueno, N.; Guillemin, R. Structural characterization of follistatin: A novel follicle-stimulating hormone release-inhibiting polypeptide from the gonad. Mol. Endocrinol. 1987, 1, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shimasaki, S.; Koga, M.; Esch, F.; Mercad, M.; Cooksey, K.; Koba, A.; Ling, N. Porcine follistatin gene structure supports two forms of mature follistatin produced by alternative splicing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988, 152, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerch, T.F.; Shimasaki, S.; Woodruff, T.K.; Jardetzky, T.S. Structural and biophysical coupling of heparin and activin binding to follistatin isoform functions. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 15930–15939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Matzuk, M.M.; Gerstmayer, B.; Bosio, A.; Lauster, R.; Miyachi, Y.; Werner, S.; Paus, R. Control of pelage hair follicle development and cycling by complex interactions between follistatin and activin. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 497–499. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, J.; Yuan, T.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ouyang, H.; Pang, D. Analysis of myostatin and its related factors in various porcine tissues. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 3099–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Tian, W.; Wang, D.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhi, Y.; Li, D.; Li, Z.; et al. Comparative analyses of dynamic transcriptome profiles highlight key response genes and dominant isoforms for muscle development and growth in chicken. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2023, 55, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yang, D.; Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, C.; Yu, C.; Li, Z. Single-cell RNA transcriptome uncovers distinct developmental trajectories in the embryonic skeletal muscle of Daheng broiler and Tibetan chicken. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Yu, M.; Wang, J.; Du, X.; Zhao, D.; Pian, H.; He, Z.; Wu, G.; Li, S.; et al. Transcriptome Profiling Identifies Differentially Expressed Genes in Skeletal Muscle Development in Native Chinese Ducks. Genes 2023, 15, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wu, J.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J.; Mao, H.; Liu, S.; Chen, B. Whole-Transcriptome RNA Sequencing Uncovers the Global Expression Changes and RNA Regulatory Networks in Duck Embryonic Myogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, S.; Chen, G.; Deng, X.; Zhang, D.; Wen, H.; Yin, Y.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, X.; Luo, W. Transcriptome Sequencing Reveals Pathways Related to Proliferation and Differentiation of Shitou Goose Myoblasts. Animals 2022, 12, 2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Ouyang, H.; Chen, X.; Jiang, D.; Tian, Y.; Huang, Y.; Shen, X. Comparative Transcriptome Analyses of Leg Muscle during Early Growth between Geese (Anser cygnoides) Breeds Differing in Body Size Characteristics. Genes 2023, 14, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, Y.; Tang, B.; Hu, J.; He, H.; Liu, H.; Li, L.; Hu, S.; Wang, J. Comparative transcriptomic analysis revealed potential mechanisms regulating the hypertrophy of goose pectoral muscles. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Nie, F.; Yin, Z.; He, J. Enhanced hyperplasia in muscles of transgenic zebrafish expressing Follistatin1. Sci. China Life Sci. 2011, 54, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, H.; Schakman, O.; Kalista, S.; Lause, P.; Tsuchida, K.; Thissen, J.P. Follistatin induces muscle hypertrophy through satellite cell proliferation and inhibition of both myostatin and activin. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 297, E157–E164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Dai, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, H.; He, D. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Role of the FST Gene in Goose Muscle Development. Animals 2025, 15, 3009. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203009

Wang C, Liu Y, Li M, Yang Y, Dai J, Chen S, Wang H, He D. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Role of the FST Gene in Goose Muscle Development. Animals. 2025; 15(20):3009. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203009

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Cui, Yi Liu, Mingxia Li, Yunzhou Yang, Jiuli Dai, Shufang Chen, Huiying Wang, and Daqian He. 2025. "Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Role of the FST Gene in Goose Muscle Development" Animals 15, no. 20: 3009. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203009

APA StyleWang, C., Liu, Y., Li, M., Yang, Y., Dai, J., Chen, S., Wang, H., & He, D. (2025). Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Role of the FST Gene in Goose Muscle Development. Animals, 15(20), 3009. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203009