Canine Hemangioblastoma: Case Series and Literature Review

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Caseload

2.2. Neuroimaging

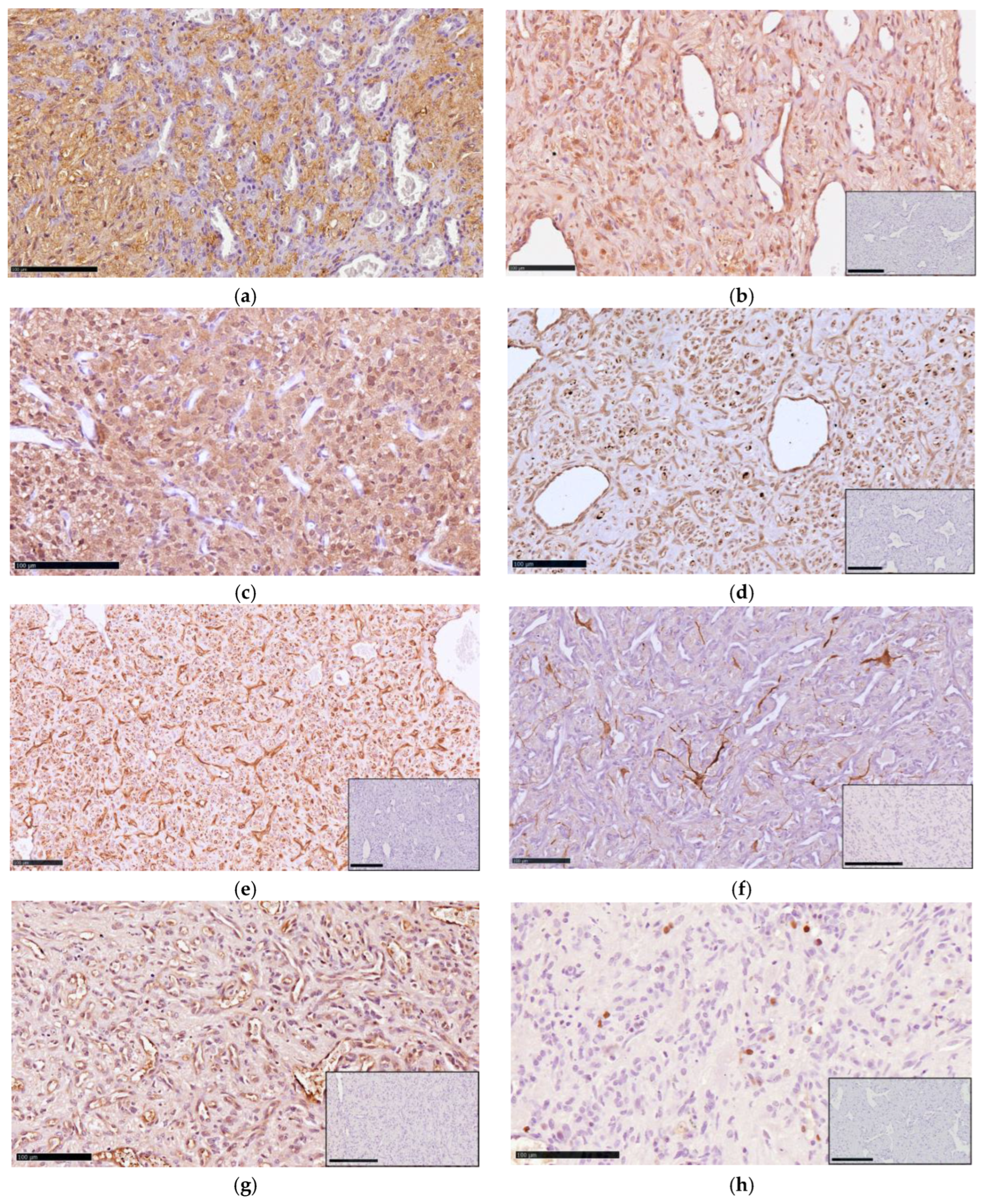

2.3. Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and Imaging Findings

3.2. Pathological Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hussein, M.R. Central nervous system capillary haemangioblastoma: The pathologist’s viewpoint. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2007, 88, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J.E.; Chou, D.; Clatterbuck, R.E.; Brem, H.; Long, D.M.; Rigamonti, D. Hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system in von Hippel-Lindau syndrome and sporadic disease. Neurosurgery 2001, 48, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lonser, R.R.; Butman, J.A.; Huntoon, K.; Asthagiri, A.R.; Wu, T.; Bakhtian, K.D.; Chew, E.Y.; Zhuang, Z.; Linehan, W.M.; Oldfield, E.H. Prospective natural history study of central nervous system hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. J. Neurosurg. 2014, 120, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, X. Clinicopathological analysis of extraneural sporadic haemangioblastoma occurring in the tongue. BMJ Case Rep. 2023, 16, e255581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, G.M.; Taylor-Weiner, A.; Lelic, N.; Jones, R.T.; Kim, J.C.; Francis, J.M.; Abedalthagafi, M.; Borges, L.F.; Coumans, J.V.; Curry, W.T.; et al. Sporadic hemangioblastomas are characterized by cryptic VHL inactivation. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2014, 2, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woltering, N.; Albers, A.; Müther, M.; Stummer, W.; Paulus, W.; Hasselblatt, M.; Holling, M.; Thomas, C. DNA methylation profiling of central nervous system hemangioblastomas identifies two distinct subgroups. Brain Pathol. 2022, 32, e13083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantile, C.; Baroni, M.; Tartarelli, C.L.; Campani, D.; Salvadori, C.; Arispici, M. Intramedullary hemangioblastoma in a dog. Vet. Pathol. 2003, 40, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Veterinary Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University College Dublin. AFIP Wednesday Slide Conference No. 17, Case III–N121-97 (AFIP 2600033). Washington, DC, USA, 1998. Available online: http://www.askjpc.org/wsco/wsc/wsc97/97wsc17.htm (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Liebel, F.X.; Summers, B.A.; Lowrie, M.; Smith, P.; Garosi, L. Imaging diagnosis-magnetic resonance imaging features of a cerebral hemangioblastoma in a dog. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2013, 54, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binanti, D.; De Zani, D.; Fantinato, E.; Allevi, G.; Sironi, G.; Zani, D. Intradural extramedullary haemangioblastoma with paraspinal extension in a dog. Aust. Vet. J. 2015, 93, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaels, J.; Thomas, W.; Ferguson, S.; Hecht, S. Clinical features of spinal cord hemangioblastoma in a dog. Front. Vet. Sci. 2015, 2, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecht, S.; Davenport, S.; Hodshon, A.; LoBato, D. What is your diagnosis? J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2018, 252, 533–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsgaard, K.; Jean, S.S.; Lovell, S.; Levine, J.; Gremillion, C.; Summers, B.; Rech, R.R. Case report: Hemangioblastoma in the brainstem of a dog. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1126477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordy, D.R. Vascular malformations and hemangiomas of the canine spinal cord. Vet. Pathol. 1979, 16, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, J.; Miranda, I.C.; Miller, A.D.; Summers, B.A. A review of proliferative vascular disorders of the central nervous system of animals. Vet. Pathol. 2021, 58, 864–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaman, T.; Karasu, A.; Uyar, A.; Kuşçu, Y.; Keleş, Ö.F. Congenital extraneural hemangioblastoma in a lamb. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2019, 31, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasulic, L.; Samardzic, M.; Bascarevic, V.; Micovic, M.; Cvrkota, I.; Zivkovic, B. A rare case of peripheral nerve hemangioblastoma—Case report and literature review. Neurosurg. Rev. 2015, 38, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanebo, J.E.; Lonser, R.R.; Glenn, G.M.; Oldfield, E.H. The natural history of hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J. Neurosurg. 2003, 98, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ene, C.I.; Morton, R.P.; Ferreira, M., Jr.; Sekhar, L.N.; Kim, L.J. Spontaneous hemorrhage from central nervous system hemangioblastomas. World Neurosurg. 2015, 83, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierscianek, D.; Wolf, S.; Keyvani, K.; El Hindy, N.; Stein, K.P.; Sandalcioğlu, I.E.; Sure, U.; Mueller, O.; Zhu, Y. Study of angiogenic signaling pathways in hemangioblastoma. Neuropathology 2017, 37, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tihan, T.; Fanburg-Smith, J.C.; Vortmeyer, A.O.; Zagzag, D. Haemangioblastoma. In WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Central Nervous System Tumours, 5th ed.; WHO Classification of Tumours Series; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2021; Volume 6, pp. 310–313. [Google Scholar]

- Maslinska, D.; Wozniak, R.; Kaliszek, A.; Schmidt-Sidor, B.; Lipska, A.; Woolley, D.E. Phenotype of mast cells in the brain tumor. Capillary hemangioblastoma. Folia Neuropathol. 1999, 37, 138–142. [Google Scholar]

- Vandevelde, M.; Fankhauser, R. Zur Pathologie der Rückenmarksblutungen beim Hund. Schweiz Arch. Tierheilkd. 1972, 114, 464–475. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, T.M.; Morrison, J.; Summers, B.A.; DeLahunta, A.; Schatzberg, S.J. Meningioangiomatosis in young dogs: A case series and literature review. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2004, 18, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R.; Johnston, P.; Wessmann, A.; Penderis, J. Imaging diagnosis—Canine meningioangiomatosis. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2010, 51, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.D.; Miller, C.R.; Rossmeisl, J.H. Canine primary intracranial cancer: A clinicopathologic and comparative review of glioma, meningioma, and choroid plexus tumors. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardo, T.; Pagano, T.B.; Piparo, S.L.; Bifara, V.; Bono, F.; Ruffino, S.; Cinti, F. Vertebral angiomatosis in a dog. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2024, 60, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jull, P.; Walmsley, G.L.; Benigni, L.; Wenzlow, N.; Rayner, E.L.; Summers, B.A.; Cherubini, G.B.; Schöniger, S.; Volk, H.A. Imaging diagnosis--spinal cord hemangioma in two dogs. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2011, 52, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaki, F.A. Vascular malformation (cavernous angioma) of the spinal cord in a dog. J. Small Anim. Pract. 1979, 20, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, S.G.; Bagley, R.S.; Gavin, P.R.; Konzik, R.L.; Cantor, G.H. Surgical treatment of an intramedullary spinal cord hamartoma in a dog. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2002, 221, 659–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantile, C.; Youssef, S. Nervous System. In Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, 6th ed.; Maxie, M.G., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 1, p. 398. [Google Scholar]

- Vandevelde, M.; Higgins, R.J.; Oevermann, A. Veterinary Neuropathology: Essentials of Theory and Practice, 1st ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2012; p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- Tekavec, K.; Švara, T.; Knific, T.; Gombač, M.; Cantile, C. Histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluation of canine nerve sheath tumors and proposal for an updated classification. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 204–230. [Google Scholar]

- Fonti, N.; Parisi, F.; Aytaş, Ç.; Degl’Innocenti, S.; Cantile, C. Neuropathology of central and peripheral nervous system lymphoma in dogs and cats: A study of 92 cases and review of the literature. Animals 2023, 13, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, T.S.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Roberts, S.A.; Brooks, J.J. A detailed immunohistochemical analysis of cerebellar hemangioblastoma: An undifferentiated mesenchymal tumor. Mod. Pathol. 1989, 2, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schaller, T.; Bode, M.; Berlis, A.; Frühwald, M.C.; Lichtmannegger, I.; Endhardt, K.; Märkl, B. Specific immunohistochemical pattern of carbonic anhydrase IX is helpful for the diagnosis of CNS hemangioblastoma. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2015, 211, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barresi, V.; Vitarelli, E.; Branca, G.; Antonelli, M.; Giangaspero, F.; Barresi, G. Expression of brachyury in hemangioblastoma: Potential use in differential diagnosis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012, 36, 1052–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, E.M.; Banerjee, P.; Ellis, C.L.; Albadine, R.; Sharma, R.; Chaux, A.M.; Burger, P.C.; Netto, G.J. PAX2(-)/PAX8(-)/inhibin A(+) immunoprofile in hemangioblastoma: A helpful combination in the differential diagnosis with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma to the central nervous system. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2011, 35, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vortmeyer, A.O.; Tran, M.G.B.; Zeng, W.; Gläsker, S.; Riley, C.; Tsokos, M.; Ikejiri, B.; Merrill, M.J.; Raffeld, M.; Zhuang, Z.; et al. Evolution of VHL tumourigenesis in nerve root tissue. J. Pathol. 2006, 210, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shively, S.B.; Falke, E.A.; Li, J.; Tran, M.G.B.; Thompson, E.R.; Maxwell, P.H.; Roessler, E.; Oldfield, E.H.; Lonser, R.R.; Vortmeyer, A.O. Developmentally arrested structures preceding cerebellar tumors in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Mod. Pathol. 2011, 24, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gläsker, S.; Li, J.; Xia, J.B.; Okamoto, H.; Zeng, W.; Lonser, R.R.; Zhuang, Z.; Oldfield, E.H.; Vortmeyer, A.O. Hemangioblastomas share protein expression with embryonal hemangioblast progenitor cell. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 4167–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, A.; Zare, A.; Khaboushan, A.S.; Hajikarimloo, B.; Sheehan, J.P. Stereotactic radiosurgery in the management of central nervous system hemangioblastomas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg. Rev. 2025, 48, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antibody | Clone | Dilution | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSE | NSE-P1 | 1:200 | Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA |

| vWF | polyclonal | 1:500 | Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA |

| VIM | V9 | 1:200 | Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA |

| GFAP | polyclonal | 1:200 | Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA |

| INHα | R1 | prediluted | Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA |

| CAIX | polyclonal | 1:500 | GeneTex U.S., Irvine, CA, USA |

| Ki-67 | MIB-1 | 1:200 | Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA |

| Dog | Breed | Gender | Age (y) | Location | Origin | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Boxer | M | 8 | T9-T10 intramedullary | PM | --- |

| 2 | Mixed breed | nM | 6 | C6-C7 intramedullary | SB | no recurrence after 3 years |

| 3 | Beagle | F | 10 | C2-C3 intradural-extramedullary | SB | no recurrence |

| 4 | Labrador Retriever | nF | 9 | T12 intradural-extramedullary | SB | recurrence after 2 years |

| 5 | Yorkshire Terrier | nF | 11 | T11 intradural-extramedullary | SB | no recurrence after 3 years |

| 6 | Labrador Retriever | M | 8 | right sciatic nerve | SB | no recurrence after 18 months |

| Dog | Cellularity | Capillary Component | Inflammatory Component | Vacuolization | Desmoplasia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ++ | +++ | + | + | ++ |

| 2 | ++ | +++ | +++ | + | +++ |

| 3 | + | ++ | ++ | - | +++ |

| 4 | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| 5 | ++ | ++ | ++ | - | + |

| 6 | ++ | +++ | +++ | - | ++ |

| Breed | Gender | Age (y) | Location | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pointer | M | 6 | C5 and T5 | euthanized | [14] * |

| Australian shepherd | nF | 7 | C4-C5 | surgical resection | |

| NR | M | 8 | C7 intramedullary | euthanized | [8] |

| Pointer | M | 6 | T1 intramedullary | euthanized | [7] |

| Cross breed | NR | 9 | right olfactory bulb to frontal lobe | euthanized 2 weeks after surgical resection | [9] |

| Cross breed | nF | 8 | C1-C2 intradural extramedullary with paraspinal extension | no recurrence after 1 year | [10] |

| Yorkshire terrier | M | 2 | L3-L4 intramedullary | no recurrence after 9 months | [11] |

| Standard Poodle | F | 3 | T8 intramedullary | euthanized | [12] |

| American Pitbull Terrier | nM | 3 | brainstem intra-axial mass | euthanized | [13] |

| Lesion | Location | Vascular Morphology | Immunophenotype | Neuroimaging Features | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemangioma [23,28,29] | Intramedullary, cervical and thoracic | Numerous dilated, tightly packed, thin-walled vascular channels without intervening tissue | Endothelial cells immunoreactive with vWF; smooth muscle actin (SMA) highlights pericytes | Capillary hemangioma: hyperintense on T2WI and mildly hyperintense on T1WI with strong contrast enhancement. Cavernous hemangioma: target-like appearance in both T1WI and T2WI | Improvement of clinical signs and no evidence of recurrence after surgery |

| Vascular hamartoma [14,30] | Intramedullary, thoracic and lumbar | Proliferation of thick-walled vessels of varying caliber without intervening neuroparenchyma | No unique profile: endothelial cells may be labeled with vWF or CD31; pericytes SMA-positive | Focal hypointense on T2W sagittal images. Marked contrast enhancement on T1W transverse images | Favorable if completely resected; poor if severe compression or untreated |

| Meningioangiomatosis [15,24,25] | Leptomeninges, intramedullary cervical and thoracolumbar | Perivascular spread of a mixed population of meningothelial and fibroblastic cells invading the nervous tissue from the leptomeninges | VIM-positive spindloid cells, negative for vWF, GFAP, S-100; endothelial cells labeled with vWF, CD31; occasionally SMA-positive pericytes | Mixed T2WI signal with the hypointense center coinciding with collagen deposition; mild T1WI hyperintensity with strong contrast enhancement | Generally poor, but surgical excision can reduce clinical signs and may be curative |

| Angiomatous meningioma [26,31,32] | Intradural extramedullary | Prominent blood vessels of different sizes surrounded by whorls of neoplastic meningothelial cells | Neoplastic cells immunoreactive with VIM, CD34 and E-cadherin | Hyperintense on T1WI with strong homogeneous post-contrast enhancement and dural tail | WHO Grade I; good prognosis after total resection; surgery challenging due to vascularity and edema |

| Vertebral angiomatosis [27] | Extradural, thoracic | Non-neoplastic vasoproliferative disorder within the vertebral bone and surrounding soft tissue | Endothelial cells diffusely and strongly immunoreactive with CD31 and vWF. The cells surrounding the capillaries are negative for NSE | CT: hyperdense lesion with a honeycomb appearance causing spinal cord compression. MRI: extradural lesion, hyperintense on T1W, T2W, and STIR images, with mild and irregular contrast enhancement | Rapid improvement after surgery; clinical signs relapsed 5 months later |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aytaş, Ç.; Cauduro, A.; Falzone, C.; Gianni, S.; Tomba, A.; Cantile, C. Canine Hemangioblastoma: Case Series and Literature Review. Animals 2025, 15, 3010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203010

Aytaş Ç, Cauduro A, Falzone C, Gianni S, Tomba A, Cantile C. Canine Hemangioblastoma: Case Series and Literature Review. Animals. 2025; 15(20):3010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203010

Chicago/Turabian StyleAytaş, Çağla, Alberto Cauduro, Cristian Falzone, Stefania Gianni, Anna Tomba, and Carlo Cantile. 2025. "Canine Hemangioblastoma: Case Series and Literature Review" Animals 15, no. 20: 3010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203010

APA StyleAytaş, Ç., Cauduro, A., Falzone, C., Gianni, S., Tomba, A., & Cantile, C. (2025). Canine Hemangioblastoma: Case Series and Literature Review. Animals, 15(20), 3010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203010