Advancing Human–Animal Interaction to Counter Social Isolation and Loneliness in the Time of COVID-19: A Model for an Interdisciplinary Public Health Consortium

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Loneliness as a Public Health Crisis

3. Vulnerable Populations and the Impact of COVID-19

4. The Human–Animal Bond: Lifesaving Connection

4.1. Evidence for Health Benefits of Companion Animals

4.2. Animal Interaction and Social Capital

5. Pets and the COVID-19 Pandemic

6. Modeling Leadership by Building and Developing Consortiums: Implications on Human–Animal Interaction and Loneliness

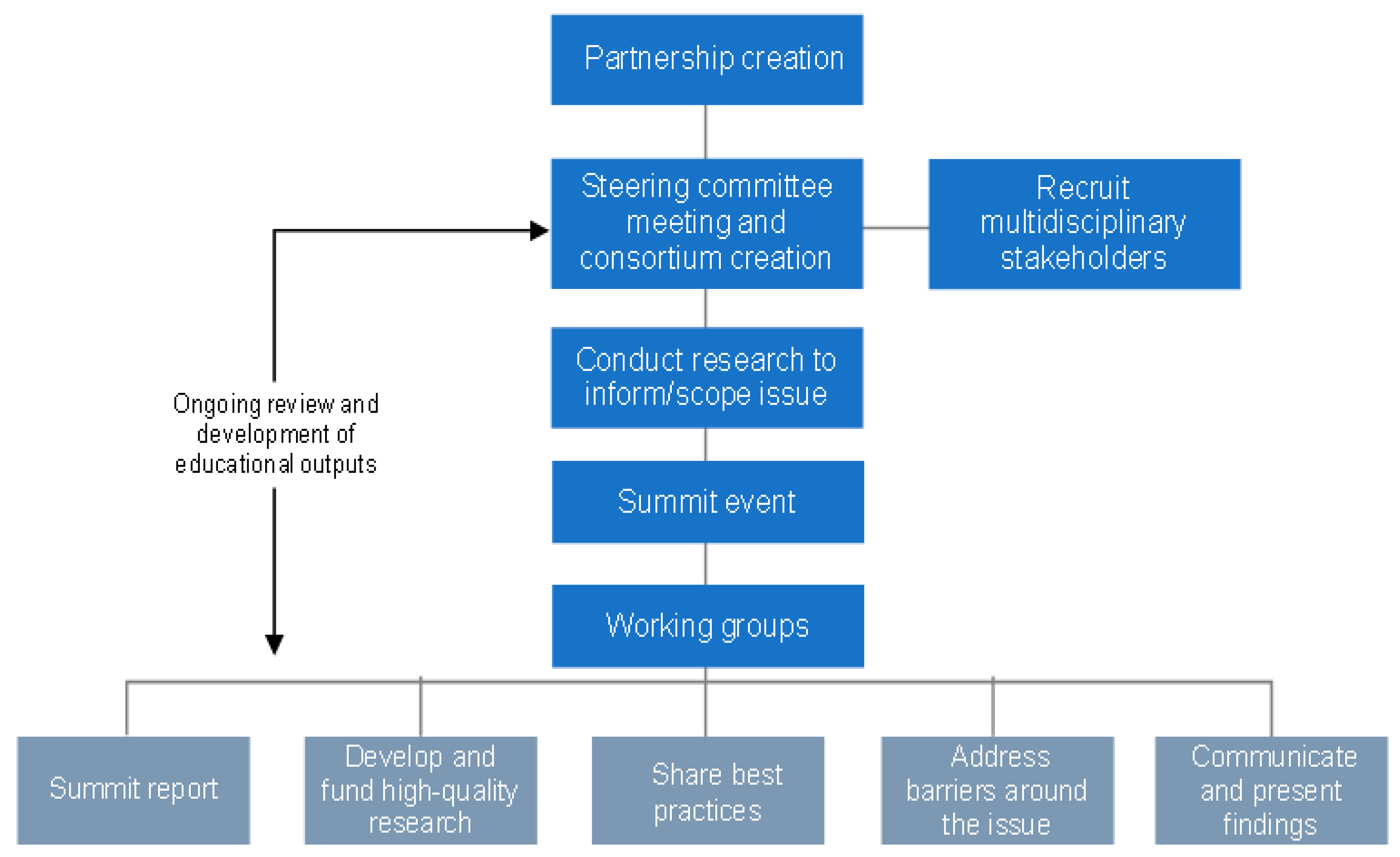

6.1. Establishing Mission and Partnership

6.2. Background

6.3. Preparation: Steering Committee and Market Research

6.4. Summit Goals and Programming

- Engage experts and stakeholders in establishing the role of companion animals in helping to prevent, mitigate, and/or alleviate social isolation across the age spectrum;

- Articulate key questions for further study to validate the benefits of HAI in this role;

- Identify barriers to realizing the benefits of HAI, particularly for people vulnerable to social isolation; and

- Propose best practices and practical solutions to address these barriers.

7. Future Vision from the Consortium: Less Isolation, More Animal Companionship

7.1. Concrete Outputs of the Consortium and Summit

- A report summarizing the goals and presentations of the May 2019 summit was created and shared with various stakeholders and the general public. Working group members reviewed and contributed to this report and assisted in sharing it widely with their respective organizations and networks.

- A research survey project has been undertaken with the Humane Rescue Alliance in Washington, DC, on the experiences and attitudes of people who adopted or fostered a new pet between March and November 2020. Preliminary findings indicate that companion animals had a profound impact on humans during this historically isolating period, and that resources for animal care and behavior management (i.e., training) should be made available to keep animal companions in the home and preserve this valuable bond.

- The working groups developed a study protocol for a novel randomized, controlled pilot study of AAI in older adults undergoing inpatient rehabilitation. The study, funded by Mars Petcare at Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine’s Center for Human–Animal Interaction, will compare animal intervention with a conversational control (a handler without a dog) and treatment as usual. This longitudinal study aims to assess the effectiveness of therapy-dog interventions in improving loneliness and health-related outcomes for patients, as well as exploring the well-being of the dogs involved, with completion expected by 2023. The results will help inform the implementation and feasibility of future large-scale, multicenter clinical trials.

7.2. Synergy as a Driver of New Initiatives

8. Conclusions: Building New Vehicles for Change

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hawkley, L.C.; Thisted, R.A. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol. Aging 2010, 25, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Division of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Social Isolation among Older Individuals: The Relationship to Mortality and Morbidity. In The Second Fifty Years: Promoting Health and Preventing Disability; Berg, R.L., Cassells, J.S., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; Volume 14. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235604/ (accessed on 14 May 2021).

- Cornwell, E.Y.; Waite, L.J. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2009, 50, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullen, R.A.; Tong, S.; Sabo, R.T.; Liaw, W.R.; Marshall, J.; Nease, D.E., Jr.; Krist, A.H.; Frey, J.J., 3rd. Loneliness in primary care patients: A prevalence study. Ann. Fam. Med. 2019, 17, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, L.D.; Wu, J.S.; Lustig, S.L.; Russell, D.W.; Nemecek, D.A. Loneliness in the United States: A 2018 National Panel Survey of Demographic, Structural, Cognitive, and Behavioral Characteristics. Am. J. Health Promot. 2019, 33, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G.O.; Thayer, C.E. Loneliness and Social Connections: A National Survey of Adults 45 and Older; AARP Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, N.M.L.; Yeung, P.P.S.; Lee, T.M.C. A developmental social neuroscience model for understanding loneliness in adolescence. Soc. Neurosci. 2016, 13, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hawkley, L.C. Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2009, 13, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naito, R.; Leong, D.P.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; McKee, M.; Subramanian, S.V.; Rangarajan, S.; Islam, S.; Avezum, A.; Yeates, K.E.; Lear, S.A.; et al. Impact of social isolation on mortality and morbidity in 20 high-income, middle-income and low-income countries in five continents. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e004124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh-Hunt, N.; Bagguley, D.; Bash, K.; Turner, V.; Turnbull, S.; Valtorta, N.; Caan, W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health 2017, 152, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantell, M.; Rehkopf, D.; Jutte, D.; Syme, S.L.; Balmes, J.; Adler, N. Social Isolation: A predictor of mortality comparable to traditional clinical risk factors. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 2056–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, A.; Harrington, H.; Moffitt, T.E.; Milne, B.J.; Poulton, R. Socially isolated children 20 years later: Risk of cardiovascular disease. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2006, 160, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perissinotto, C.M.; Stijacic Cenzer, I.; Covinsky, K.E. Loneliness in older persons: A predictor of functional decline and death. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 1078–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Cohen Silver, R.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groarke, J.M.; Berry, E.; Graham-Wisener, L.; McKenna-Plumley, P.E.; McGlinchey, E.; Armour, C. Loneliness in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional results from the COVID-19 Psychological Wellbeing Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MHA/Mental Health America. COVID-19 and Mental Health: A Growing Crisis. 2021. Available online: https://mhanational.org/research-reports/covid-19-and-mental-health-growing-crisis (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Killgore, W.D.S.; Cloonan, S.; Taylor, E.C.; Miller, M.; Dailey, N. Three months of loneliness during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinman, M.A.; Perry, L.; Perissinotto, C.M. Meeting the care needs of older adults isolated at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 819–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagcchi, S. Stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.S.; Bowlby, J. An ethological approach to personality development. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.M. The biology of the human-animal bond. Anim. Front. 2014, 4, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilcha-Mano, S.; Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Pets as safe havens and secure bases: The moderating role of pet attachment orientations. J. Res. Pers. 2012, 46, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiot, C.; Bastian, B.; Martens, P. People and companion animals: It takes two to tango. BioScience 2016, 66, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, A.R.; Brown, C.M.; Shoda, T.M.; Stayton, L.E.; Martin, C.E. Friends with benefits: On the positive consequences of pet ownership. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 1239–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, H.L.; Rushton, K.; Lovell, K.; Bee, P.; Walker, L.; Grant, L.; Rogers, A. The power of support from companion animals for people living with mental health problems: A systematic review and narrative synthesis of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, H.; Rushton, K.; Walker, S.; Lovell, K.; Rogers, A. Ontological security and connectivity provided by pets: A study in the self-management of the everyday lives of people diagnosed with a long-term mental health condition. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutt, H.; Giles-Corti, B.; Knuiman, M.; Burke, V. Dog ownership, health and physical activity: A critical review of the literature. Health Place 2007, 13, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Headey, B.; Grabka, M.M. Pets and human health in Germany and Australia: National Longitudinal Results. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 80, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, E.; Katcher, A.H.; Lynch, J.; Thomas, S. Animal companions and one-year survival of patients after discharge from a coronary care unit. Public Health Rep. 1980, 95, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Friedmann, E.; Thomas, S.A.; Son, H. Pets, depression and long term survival in community living patients following myocardial infarction. Anthrozoos 2011, 24, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNicholas, J.; Collis, G.M. Dogs as catalysts for social interactions: Robustness of the effect. Br. J. Psychol. 2000, 91, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, J.; Hart, L.A.; Boltz, R.P. The effects of service dogs on social acknowledgments of people in wheelchairs. J Psychol. 1988, 122, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.J.; Giles-Corti, B.; Bulsara, M.K.; Bosch, D.A. More than a furry companion: The ripple effect of companion animals on neighborhood interactions and sense of community. Soc. Anim. J. Hum.-Anim. Stud. 2007, 15, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Martin, K.; Christian, H.; Houghton, S.; Kawachi, I.; Vallesi, S.; McCune, S. Social capital and pet ownership–A tale of four cities. SSM Popul. Health 2017, 3, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, N.R.; Mueller, M.K. A systematic review of research on pet ownership and animal interactions among older adults. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L.; Protopopova, A.; Birkler, R.I.D.; Beata Itin-Shwartz, B.; Sutton, G.A.; Gamliel, A.; Yakobson, B.; Raz, T. Human–dog relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: Booming dog adoption during social isolation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APPA (American Pet Products Association). Pet Industry Market Size, Trends & Ownership Statistics. Available online: https://www.americanpetproducts.org/press_industrytrends.asp (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Morgan Stanley. Why Pets Could Be a Long-Tail Investment Trend. 7 April 2021. Available online: https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/us-pets-investing-trend?cid=smsp-23847534866070660_2940782372618971_23847718746880660_23847718746950660 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- APPA (American Pet Products Association). American Pet Products Association Releases Findings from COVID-19 Pulse Study of Pet Ownership during the Pandemic [Press Release]. 24 June 2020. Available online: https://www.americanpetproducts.org/press_releasedetail.asp?id=1219 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Bussolari, C.; Currin-McCulloch, J.; Packman, W.; Kogan, L.; Erdman, P. “I Couldn’t Have Asked for a Better Quarantine Partner!”: Experiences with companion dogs during Covid-19. Animals 2021, 11, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratschen, E.; Shoesmith, E.; Shahab, L.; Silva, K.; Kale, D.; Toner, P.; Reeve, C.; Mills, D.S. Human-animal relationships and interactions during the Covid-19 lockdown phase in the UK: Investigating links with mental health and loneliness. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal Canin. Press Release: “Royal Canin and Celebrity ‘Advocats’ Team Up for Annual ‘Take Your Cat to the Vet’ Campaign”. Available online: https://www.royalcanin.com/us/about-us/news/royal-canin-and-celebrity-advocats-team-up-for-annual-take-your-cat-to-the-vet-campaign (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Mars Petcare. Pets in a Pandemic: Better Cities for Pets 2020 Report. Available online: https://www.bettercitiesforpets.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/2020-Better-Cities-For-Pets-Report-Mars-Petcare-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Bennett, S.; Corluka, A.; Doherty, J.; Tangcharoensathien, V.; Patcharanarumol, W.; Jesani, A.; Kyabaggu, J.; Namaganda, G.; Hussain, A.M.; de-Graft Aikins, A. Influencing policy change: The experience of health think tanks in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan. 2012, 27, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Shaw, S.E.; Russell, J.; Greenhalgh, T.; Korica, M. Thinking about think tanks in health care: A call for a new research agenda. Sociol Health Illn. 2014, 36, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HABRI, Mars Petcare. Addressing the Social Isolation & Loneliness Epidemic with the Power of Companion Animals: A report by the Consortium on Social Isolation and Companion Animals. 2019. Available online: https://habri.org/assets/uploads/Addressing-the-Social-Isolation-and-Loneliness-Epidemic-with-the-Power-of-Companion-Animals-Report.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- HABRI. New Effort Highlights Potential Impact of Pets on Social Isolation and Loneliness (Press Release, 7 May 2019). Available online: https://habri.org/pressroom/20190507 (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Hughes, A.M.; Braun, L. The potential for pets to help alleviate the epidemic of loneliness and social isolation and lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. In Proceedings of the 30th International Society for Anthrozoology Conference, Held Virtually, 22 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, A.M.; Feldman, S. The Power of Pets: The Veterinary Community’s Role in Addressing the Social Isolation and Loneliness Crisis. In Proceedings of the American Veterinary Medical Association 2021 Convention, Held Virtually, 30 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, D.C.; Friedmann, E.; Sachs-Ericsson, N.; Gilchrist, C. Do Pets Buffer Feelings of Loneliness During Difficult Life Events? Insights from the COVID-19 Pandemic for Loneliness and Older Adults. Animals 2021, 11, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Z.; Griffin, T.C.; Braun, L. The New Status Quo: Enhancing Access to Human-Animal Interactions to Alleviate Social Isolation & Loneliness in the Time of COVID-19. Animals 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Banfield Pet Hospital. Survey Reveals Pandemic Pet Owners Worried about Returning to the Workplace, While Employers Plan to Offer New Pet-Friendly Policies. 4 March 2021. Available online: https://www.banfield.com/about-banfield/newsroom/press-releases/2021/survey-reveals-pandemic-pet-owners-worried-about-returning-to-the-workplace-while-employers-plan (accessed on 16 May 2021).

- 2022 Sponsorship for Human-Animal Bond Studies. Available online: https://www.purina.com/articles/2022-sponsorship-human-animal-bond-studies (accessed on 13 June 2021).

| 80% of pet owners reported that their pet makes them feel less lonely. |

| 51% of pet owners said their pet helps them feel less shy. |

| Among both pet owners and non-pet owners, 85% of respondents believed interaction with a companion animal reduces loneliness and 76% agreed that human–animal interactions can help address social isolation; among pet owners, those with the closest bond to their pet saw the highest positive impact on feelings of loneliness and social isolation. |

| 54% of respondents said their pet helped them connect with other people. |

| 89% of pet owners who adopted a pet due to loneliness believed their pet helped them feel less lonely. |

| 26% of pet owners reported having adopted a pet because they believed it was good for mental health; respondents aged > 55 y reported doing so more frequently. |

| Research Quality |

|---|

| Establish standardized and well-validated outcome measures |

| Design studies with rigorous methodology (comparison groups, sample sizes) |

| Describe methodology adequately to permit replication |

| Elevate diversity in research populations and access to programming |

| Research questions: |

| Include qualitative as well as quantitative measures of HAI (beyond “pet/no pet” binary to include relationships and interactions) |

| Consider unmet needs of underserved communities and vulnerable populations |

| Explore underlying mechanisms for documented benefits |

| Study the impact of HAI on the animals and their well-being |

| Follow-up activities: |

| Share data from smaller trials to enrich resources for the research community |

| Move research outcomes into practice, via specific, evidence-based guidance for specific populations |

| Develop clear, informative messaging for stakeholders to leverage research findings for maximum benefit |

| In older adults: |

| Examine the role of animal companionship in navigating life transitions such as retirement or loss of a spouse |

| Plan longitudinal studies to explore the value of pets to healthy aging |

| In people with mental health challenges: |

| Elucidate optimal circumstances for HAI, including animal-assisted therapy |

| Evaluate the efficacy of interventions, including patient satisfaction |

| Identify differences in HAI for this population and their implications in practice |

| HAI, human–animal interaction. |

| Recruit a diverse, multidisciplinary group of experts to form an advisory or steering committee. Their task is to prioritize focus areas for a larger consortium effort and identify key stakeholders to invite as participants. This committee can help develop the agenda and suggest speakers for a summit event and participate in the creation of outputs such as a summary report. |

| Develop a communication plan to promote the event to the public, possibly with the professional help of a public relations team. Consider using interview content from event participants for earned or social media exposure. Even post-event promotion helps raise awareness and heightens interest in its goals and outcomes. |

| In choosing a date for an event, keep in mind months of recognition or special awareness holidays, e.g., HABRI/Mars Petcare held the 2019 summit in May, during Mental Health Month. |

| Consider offering sponsorship opportunities for certain stakeholders to offset costs while also raising the profile of the event. |

| With the steering committee/advisory group recommendations in mind, invite a broad group of stakeholders to attend the summit event. Plan to include speaker Q&As, discussion groups, or other means of connecting and engaging event participants with one another. |

| Ask the steering committee to brainstorm outcomes and key takeaways from the event, and request that they come prepared with next steps or direct “asks” for the audience to consider. |

| After the event, create an action plan that involves participants, the steering committee, and others. Before the HABRI/Mars Petcare summit, plans were laid out to create and disseminate a report summarizing the event and the consortium’s overall effort, including a detailed account of the recommendations borne out of the discussions. |

| Offer summit event participants the opportunity to join working groups and encourage ongoing service by steering committee members to ensure continuity. Our working groups were tasked with promoting the consortium’s goals of advancing research, sharing best practices, and addressing barriers. HABRI and Mars Petcare have continued to engage and support working-group members with invitations to present on the consortium’s efforts and participate in other relevant conferences. |

| Consider the areas of expertise of steering committee members and participants: Are they researchers, policy makers, or service providers? HABRI and Mars Petcare balanced each working group to include researchers and practitioners from varied backgrounds so that each individual could bring something unique to the table. |

| HABRI, Human Animal Bond Research Institute. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hughes, A.M.; Braun, L.; Putnam, A.; Martinez, D.; Fine, A. Advancing Human–Animal Interaction to Counter Social Isolation and Loneliness in the Time of COVID-19: A Model for an Interdisciplinary Public Health Consortium. Animals 2021, 11, 2325. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082325

Hughes AM, Braun L, Putnam A, Martinez D, Fine A. Advancing Human–Animal Interaction to Counter Social Isolation and Loneliness in the Time of COVID-19: A Model for an Interdisciplinary Public Health Consortium. Animals. 2021; 11(8):2325. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082325

Chicago/Turabian StyleHughes, Angela M., Lindsey Braun, Alison Putnam, Diana Martinez, and Aubrey Fine. 2021. "Advancing Human–Animal Interaction to Counter Social Isolation and Loneliness in the Time of COVID-19: A Model for an Interdisciplinary Public Health Consortium" Animals 11, no. 8: 2325. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082325

APA StyleHughes, A. M., Braun, L., Putnam, A., Martinez, D., & Fine, A. (2021). Advancing Human–Animal Interaction to Counter Social Isolation and Loneliness in the Time of COVID-19: A Model for an Interdisciplinary Public Health Consortium. Animals, 11(8), 2325. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082325