The Role of Biofilm-Derived Compounds in Microbial and Protozoan Interactions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Survey Methodology

3. Biofilm-Secreted Compounds: Classification and Mechanisms

3.1. QS Molecules

3.2. Secondary Metabolites

3.3. Antimicrobial Peptides and Bacteriocins

3.4. Exopolysaccharides (EPS) and eDNA

3.5. Redox-Active Molecules and Reactive Oxygen Species (ROSs)

3.6. OMVs

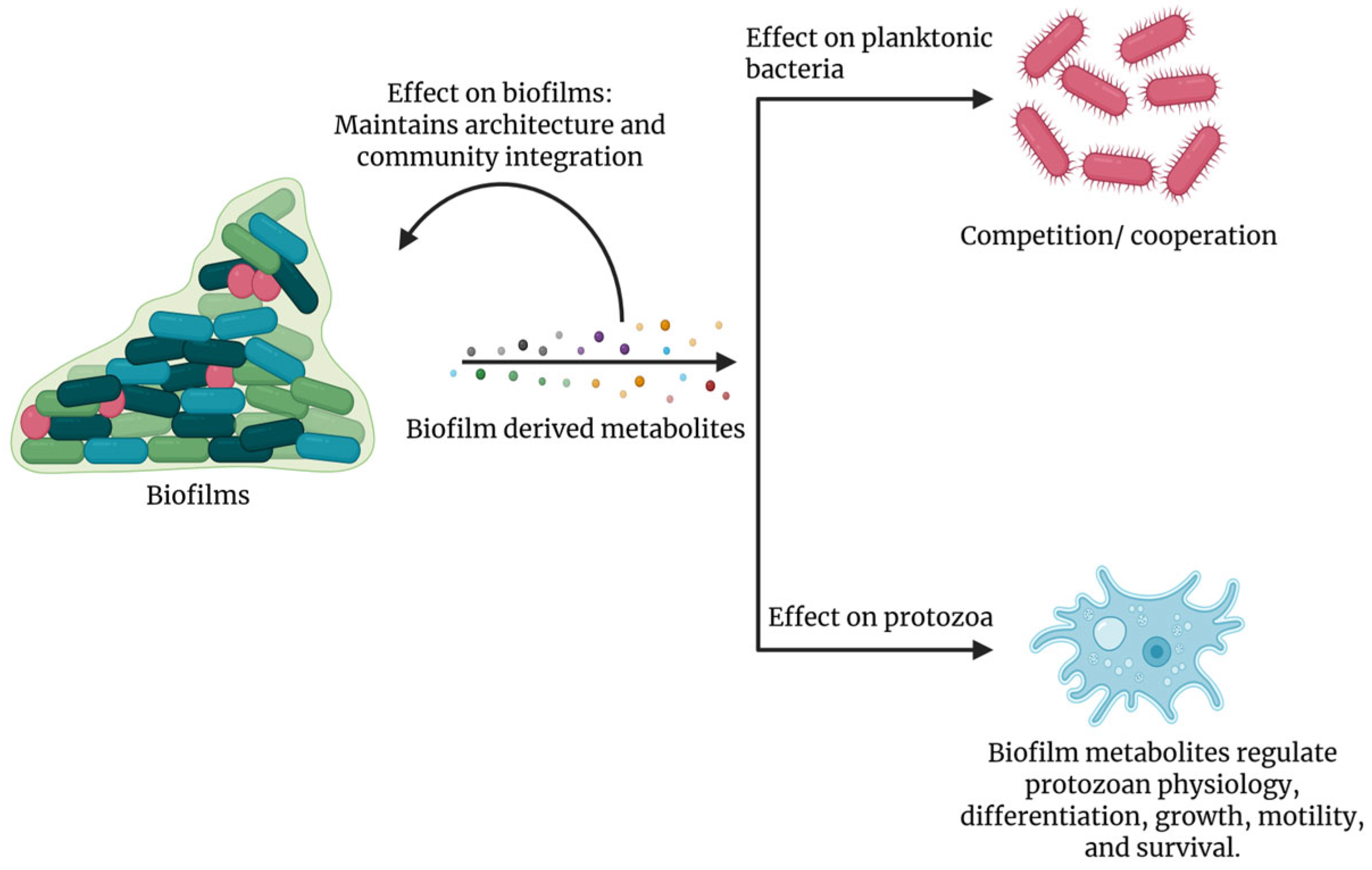

4. Effects of Compounds Secreted by Biofilms on Bacterial Competitors and Protozoan Predators

4.1. SCFAs

4.2. AHLs

4.3. Phenazines

4.4. Indole

4.5. Violacein

4.6. Reactive Sulfur Species (RSSs)

5. Protozoan Responses to Biofilm-Derived Compounds

5.1. SCFAs

5.2. AHLs

5.3. Phenazine

5.4. Indole

5.5. Violacein

5.6. RSSs

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHLs | Acyl-homoserine lactones |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| RSS | Reactive sulfur species |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| eDNA | Extracellular DNA |

| AI-2 | Autoinducer-2 |

| QS | Quorum sensing |

| OMVs | Outer membrane vesicles |

| AIPs | Autoinducing peptides |

| fMLP | Formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine |

| VOC | Volatile organic compounds |

| AMPs | Antimicrobial peptides |

| EPS | Exopolysaccharides |

| PIA | Polysaccharide intercellular adhesin |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| PCA | Phenazine-1-carboxylic acid |

| TnaA | Tryptophanase |

| H2S | Hydrogen sulfide |

| Cys-SSH | Cysteine persulfide |

References

- Flemming, H.-C.; Wingender, J.; Szewzyk, U.; Steinberg, P.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S. Biofilms: An Emergent Form of Bacterial Life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamford, N.C.; MacPhee, C.E.; Stanley-Wall, N.R. Microbial Primer: An Introduction to Biofilms—What They Are, Why They Form and Their Impact on Built and Natural Environments: This Article Is Part of the Microbial Primer Collection. Microbiology 2023, 169, 001338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimkes, T.E.P.; Heinemann, M. How Bacteria Recognise and Respond to Surface Contact. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 44, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Prentice, E.L.; Webber, M.A. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in Biofilms. NPJ Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadell, C.D.; Xavier, J.B.; Foster, K.R. The Sociobiology of Biofilms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 33, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katharios-Lanwermeyer, S.; O’Toole, G.A. Biofilm Maintenance as an Active Process: Evidence That Biofilms Work Hard to Stay Put. J. Bacteriol. 2022, 204, e0058721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.V.; Gunawan, C.; Mann, R. We Are One: Multispecies Metabolism of a Biofilm Consortium and Their Treatment Strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 635432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.-L.; Bassler, B.L. Bacterial Quorum-Sensing Network Architectures. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009, 43, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J.P.; Passador, L.; Iglewski, B.H.; Greenberg, E.P. A Second N-Acylhomoserine Lactone Signal Produced by Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 1490–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Zhang, L. The Hierarchy Quorum Sensing Network in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Protein Cell 2015, 6, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennoune, N.; Andriamihaja, M.; Blachier, F. Production of Indole and Indole-Related Compounds by the Intestinal Microbiota and Consequences for the Host: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.; Im, J.; Kim, A.R.; Lee, D.; Jeong, S.; Yun, C.-H.; Han, S.H. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Inhibit the Biofilm Formation of Streptococcus gordonii Through Negative Regulation of Competence-Stimulating Peptide Signaling Pathway. J. Microbiol. 2021, 59, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz, C.; Kjelleberg, S. Off the Hook--How Bacteria Survive Protozoan Grazing. Trends Microbiol. 2005, 13, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolodkin-Gal, I.; Murugan, P.A.; Mahapatra, S.; Zanditenas, E.; Ankri, S. Differential Coping Strategies Exerted by Biofilm and Planktonic Cells of Bacillus subtilis in Response to a Protozoan Predator. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, e0159725, epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.M.; Espinoza-Vergara, G.; McDougald, D. Protozoan Predation as a Driver of Diversity and Virulence in Bacterial Biofilms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 47, fuad040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz, C.; McDougald, D.; Moreno, A.M.; Yung, P.Y.; Yildiz, F.H.; Kjelleberg, S. Biofilm Formation and Phenotypic Variation Enhance Predation-Driven Persistence of Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 16819–16824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunma, C.; Noinarin, P.; Phetcharaburanin, J.; Chareonsudjai, S. Burkholderia Pseudomallei Biofilm Resists Acanthamoeba sp. Grazing and Produces 8-O-4′-Diferulic Acid, a Superoxide Scavenging Metabolite After Passage Through the Amoeba. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noorian, P.; Hu, J.; Chen, Z.; Kjelleberg, S.; Wilkins, M.R.; Sun, S.; McDougald, D. Pyomelanin Produced by Vibrio cholerae Confers Resistance to Predation by Acanthamoeba Castellanii. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 93, fix147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.R.; Camacho, F.; Sousa, M.L.; Luelmo, S.; Santarém, N.; Cordeiro-da-Silva, A.; Leão, P.N. The Cyanobacterial Oxadiazine Nocuolin A Shows Broad-Spectrum Toxicity Against Protozoans and the Nematode C. elegans. Microb. Ecol. 2025, 88, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, J.; Faigle, W.; Eichinger, D. Colonic Short-Chain Fatty Acids Inhibit Encystation of Entamoeba invadens. Cell Microbiol. 2005, 7, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesel, J.; Shuman, J.; Bastuzel, I.; Dickerson, J.; Ingram-Smith, C. Encystation of Entamoeba Histolytica in Axenic Culture. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salusso, A.; Zlocowski, N.; Mayol, G.F.; Zamponi, N.; Rópolo, A.S. Histone Methyltransferase 1 Regulates the Encystation Process in the Parasite Giardia Lamblia. FEBS J. 2017, 284, 2396–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowska, K.; Szymanek-Majchrzak, K.; Pituch, H.; Majewska, A. Understanding Quorum-Sensing and Biofilm Forming in Anaerobic Bacterial Communities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.B.; Bassler, B.L. Quorum Sensing in Bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001, 55, 165–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, M.; Wang, R.; Xie, L.; Liu, Q.; Xie, X.; Shang, D.; et al. Sensing of Autoinducer-2 by Functionally Distinct Receptors in Prokaryotes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Styles, M.J.; Early, S.A.; Tucholski, T.; West, K.H.J.; Ge, Y.; Blackwell, H.E. Chemical Control of Quorum Sensing in E. coli: Identification of Small Molecule Modulators of SdiA and Mechanistic Characterization of a Covalent Inhibitor. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 3092–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Houdt, R.; Aertsen, A.; Moons, P.; Vanoirbeek, K.; Michiels, C.W. N-Acyl-L-Homoserine Lactone Signal Interception by Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006, 256, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.-C.; Sun, Q.; Fu, C.-Y.; She, X.; Liu, X.-C.; He, Y.; Ai, Q.; Li, L.-Q.; Wang, Z.-L. Exogenous Autoinducer-2 Rescues Intestinal Dysbiosis and Intestinal Inflammation in a Neonatal Mouse Necrotizing Enterocolitis Model. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 694395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, F.L.; Levandowsky, M. Chemosensory Responses of Acanthamoeba Castellanii: Visual Analysis of Random Movement and Responses to Chemical Signals. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 1996, 43, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raaijmakers, J.M.; Mazzola, M. Diversity and Natural Functions of Antibiotics Produced by Beneficial and Plant Pathogenic Bacteria. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2012, 50, 403–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrain, B.; Farag, M.A.; Ryu, C.-M.; Ghigo, J.-M. Role of Bacterial Volatile Compounds in Bacterial Biology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 39, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.C.; Leveau, J.; McSpadden Gardener, B.B.; Pierson, E.A.; Pierson, L.S.; Ryu, C.-M. The Multifactorial Basis for Plant Health Promotion by Plant-Associated Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 1548–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq Meo, S.; Van de Wiele, T.; Defoirdt, T. Indole Signaling in Escherichia coli: A Target for Antivirulence Therapy? Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2499573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanditenas, E.; Geffen, M.T.; Saito-Nakano, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Hisaeda, H.; Nozaki, T.; Guo, Y.; Mahapatra, S.; Wolfenson, H.; Ankri, S. The Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolite Indole Regulates Cytoskeletal Functions and Virulence in Entamoeba histolytica. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreth, J.; Zhang, Y.; Herzberg, M.C. Streptococcal Antagonism in Oral Biofilms: Streptococcus Sanguinis and Streptococcus gordonii Interference with Streptococcus Mutans. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 4632–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, P.K.; Liu, W.; Sabbe, K.; Houf, K.; Burmølle, M.; Sørensen, S.J. Synergistic Interactions within a Multispecies Biofilm Enhance Individual Species Protection against Grazing by a Pelagic Protozoan. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matz, C.; Deines, P.; Boenigk, J.; Arndt, H.; Eberl, L.; Kjelleberg, S.; Jürgens, K. Impact of Violacein-Producing Bacteria on Survival and Feeding of Bacterivorous Nanoflagellates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 1593–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentzer, M.; Teitzel, G.M.; Balzer, G.J.; Heydorn, A.; Molin, S.; Givskov, M.; Parsek, M.R. Alginate Overproduction Affects Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm Structure and Function. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 5395–5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghita, A.A.; Wozniak, D.J.; Parsek, M.R.; Howell, P.L. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm Exopolysaccharides: Assembly, Function, and Degradation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 47, fuad060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, C.; Kidder, J.B.; Jacobson, E.R.; Otto, M.; Proctor, R.A.; Somerville, G.A. Staphylococcus Epidermidis Polysaccharide Intercellular Adhesin Production Significantly Increases during Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Stress. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 2967–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, A.; Roske, Y.; Ball, L.; Chowdhury, A.; Hiller, M.; Molière, N.; Kramer, R.; Stöppler, D.; Worth, C.L.; Schlegel, B.; et al. Structural Changes of TasA in Biofilm Formation of Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 3237–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erskine, E.; Morris, R.J.; Schor, M.; Earl, C.; Gillespie, R.M.C.; Bromley, K.M.; Sukhodub, T.; Clark, L.; Fyfe, P.K.; Serpell, L.C.; et al. Formation of Functional, Non-Amyloidogenic Fibres by Recombinant Bacillus subtilis TasA. Mol. Microbiol. 2018, 110, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, N.; Keren-Paz, A.; Hou, Q.; Doron, S.; Yanuka-Golub, K.; Olender, T.; Hadar, R.; Rosenberg, G.; Jain, R.; Cámara-Almirón, J.; et al. The Extracellular Matrix Protein TasA Is a Developmental Cue That Maintains a Motile Subpopulation within Bacillus subtilis Biofilms. Sci. Signal 2020, 13, eaaw8905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Ye, J.; Shemesh, A.; Odeh, A.; Trebicz-Geffen, M.; Wolfenson, H.; Ankri, S. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli Induces Entamoeba Histolytica Superdiffusion Movement on Fibronectin by Reducing Traction Forces. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1012618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.K.; Rajpurohit, Y.S. Multitasking Functions of Bacterial Extracellular DNA in Biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 2024, 206, e0000624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez de Aldecoa, A.L.; Zafra, O.; González-Pastor, J.E. Mechanisms and Regulation of Extracellular DNA Release and Its Biological Roles in Microbial Communities. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berne, C.; Zappa, S.; Brun, Y.V. eDNA-Stimulated Cell Dispersion from Caulobacter Crescentus Biofilms upon Oxygen Limitation Is Dependent on a Toxin-Antitoxin System. Elife 2023, 12, e80808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cáp, M.; Váchová, L.; Palková, Z. Reactive Oxygen Species in the Signaling and Adaptation of Multicellular Microbial Communities. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2012, 2012, 976753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franza, T.; Gaudu, P. Quinones: More than Electron Shuttles. Res. Microbiol. 2022, 173, 103953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, S.S.; Rowe, J.J. Antibiotic Action of Pyocyanin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1981, 20, 814–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kern, S.E.; Newman, D.K. Endogenous Phenazine Antibiotics Promote Anaerobic Survival of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa via Extracellular Electron Transfer. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cezairliyan, B.; Vinayavekhin, N.; Grenfell-Lee, D.; Yuen, G.J.; Saghatelian, A.; Ausubel, F.M. Identification of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Phenazines That Kill Caenorhabditis Elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.; Sood, A.; Hogan, D.A. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa-Candida Albicans Interactions: Localization and Fungal Toxicity of a Phenazine Derivative. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitsch, D.; Kolarich, D.; Duchêne, M. The Flavin Inhibitor Diphenyleneiodonium Renders Trichomonas Vaginalis Resistant to Metronidazole, Inhibits Thioredoxin Reductase and Flavin Reductase, and Shuts off Hydrogenosomal Enzymatic Pathways. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2010, 171, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulansari, D.; Jeelani, G.; Yazaki, E.; Nozaki, T. Identification and Characterization of Archaeal-Type FAD Synthase as a Novel Tractable Drug Target from the Parasitic Protozoa Entamoeba Histolytica. mSphere 2024, 9, e0034724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.V.; López-Sánchez, A.; Junqueira, H.C.; Rivas, L.; Baptista, M.S.; Orellana, G. Riboflavin Derivatives for Enhanced Photodynamic Activity against Leishmania Parasites. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashiro, Y.; Uchiyama, H.; Nomura, N. Multifunctional Membrane Vesicles in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 1349–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, L.; Miao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Ruan, J.; Xu, L.; Guo, H.; Zhang, M.; Qiao, W. Regulation of the Formation and Structure of Biofilms by Quorum Sensing Signal Molecules Packaged in Outer Membrane Vesicles. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 151403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecil, J.D.; Sirisaengtaksin, N.; O’Brien-Simpson, N.M.; Krachler, A.M. Outer Membrane Vesicle-Host Cell Interactions. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Xiao, J.; Wang, S.; Zhou, J.; Qin, J.; Jia, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, H. Research Progress on Bacterial Membrane Vesicles and Antibiotic Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi Badi, S.; Bruno, S.P.; Moshiri, A.; Tarashi, S.; Siadat, S.D.; Masotti, A. Small RNAs in Outer Membrane Vesicles and Their Function in Host-Microbe Interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, L.H.M.; Elgamoudi, B.; Colon, N.; Cramond, A.; Poly, F.; Ying, L.; Korolik, V.; Ferrero, R.L. Campylobacter Jejuni Extracellular Vesicles Harboring Cytolethal Distending Toxin Bind Host Cell Glycans and Induce Cell Cycle Arrest in Host Cells. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0323223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcilla, A.; Martin-Jaular, L.; Trelis, M.; de Menezes-Neto, A.; Osuna, A.; Bernal, D.; Fernandez-Becerra, C.; Almeida, I.C.; Del Portillo, H.A. Extracellular Vesicles in Parasitic Diseases. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 25040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, S.A.; Tasca, T. Extracellular Vesicles in Parasitic Diseases—From Pathogenesis to Future Diagnostic Tools. Microbes Infect. 2024, 26, 105310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Jian, Y.-P.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Li, Y.; Gu, L.-T.; Sun, H.-H.; Liu, M.-D.; Zhou, H.-L.; Wang, Y.-S.; Xu, Z.-X. Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Diseases. Cell Commun. Signal 2023, 21, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, A.; Olmo, B.; Lopez-Gonzalvez, A.; Cornejo, L.; Rupérez, F.J.; Barbas, C. Capillary Electrophoresis for Short Chain Organic Acids in Faeces Reference Values in a Mediterranean Elderly Population. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2008, 46, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Garza, D.R.; Gonze, D.; Krzynowek, A.; Simoens, K.; Bernaerts, K.; Geirnaert, A.; Faust, K. Starvation Responses Impact Interaction Dynamics of Human Gut Bacteria Bacteroides Thetaiotaomicron and Roseburia Intestinalis. ISME J. 2023, 17, 1940–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charania, R.; Wade, B.E.; McNair, N.N.; Mead, J.R. Changes in the Microbiome of Cryptosporidium-Infected Mice Correlate to Differences in Susceptibility and Infection Levels. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobl, J.S.; Cassell, M.; Mitchell, S.M.; Reilly, C.M.; Lindsay, D.S. Scriptaid and Suberoylanilide Hydroxamic Acid Are Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors with Potent Anti-Toxoplasma Gondii Activity in Vitro. J. Parasitol. 2007, 93, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enshaeieh, M.; Saadatnia, G.; Babaie, J.; Golkar, M.; Choopani, S.; Sayyah, M. Valproic Acid Inhibits Chronic Toxoplasma Infection and Associated Brain Inflammation in Mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e0100321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.R.; Heilmann, S.; Mittler, J.E.; Greenberg, E.P. Acyl-Homoserine Lactone-Dependent Eavesdropping Promotes Competition in a Laboratory Co-Culture Model. ISME J. 2012, 6, 2219–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, K.A.; Manna, A.C.; Cheung, A.L. SarT Influences sarS Expression in Staphylococcus Aureus. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 5139–5148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, S.; Middleton, B.; Muharram, S.H.; Cockayne, A.; Hill, P.; O’Shea, P.; Chhabra, S.R.; Cámara, M.; Williams, P. N-Acylhomoserine Lactones Antagonize Virulence Gene Expression and Quorum Sensing in Staphylococcus Aureus. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamber, S.; Cheung, A.L. SarZ Promotes the Expression of Virulence Factors and Represses Biofilm Formation by Modulating SarA and Agr in Staphylococcus Aureus. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz, C.; Bergfeld, T.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S. Microcolonies, Quorum Sensing and Cytotoxicity Determine the Survival of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilms Exposed to Protozoan Grazing. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 6, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosson, P.; Zulianello, L.; Join-Lambert, O.; Faurisson, F.; Gebbie, L.; Benghezal, M.; Van Delden, C.; Curty, L.K.; Köhler, T. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Virulence Analyzed in a Dictyostelium Discoideum Host System. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 3027–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, Y.F.; Røder, H.L.; Chan, S.H.; Ismail, M.H.; Madsen, J.S.; Lee, K.W.K.; Sørensen, S.J.; Givskov, M.; Burmølle, M.; Rice, S.A.; et al. Associational Resistance to Predation by Protists in a Mixed Species Biofilm. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e0174122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queck, S.-Y.; Weitere, M.; Moreno, A.M.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S. The Role of Quorum Sensing Mediated Developmental Traits in the Resistance of Serratia Marcescens Biofilms against Protozoan Grazing. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 8, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempes, C.P.; Okegbe, C.; Mears-Clarke, Z.; Follows, M.J.; Dietrich, L.E.P. Morphological Optimization for Access to Dual Oxidants in Biofilms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Sekedat, M.D.; Cornell, W.C.; Silva, G.M.; Okegbe, C.; Price-Whelan, A.; Vogel, C.; Dietrich, L.E.P. Phenazines Regulate Nap-Dependent Denitrification in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 2018, 200, e00031-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, L.; Götz, F. Molecular Mechanisms of Staphylococcus and Pseudomonas Interactions in Cystic Fibrosis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 824042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filkins, L.M.; Graber, J.A.; Olson, D.G.; Dolben, E.L.; Lynd, L.R.; Bhuju, S.; O’Toole, G.A. Coculture of Staphylococcus Aureus with Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Drives S. Aureus towards Fermentative Metabolism and Reduced Viability in a Cystic Fibrosis Model. J. Bacteriol. 2015, 197, 2252–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashburn, L.M.; Jett, A.M.; Akins, D.R.; Whiteley, M. Staphylococcus Aureus Serves as an Iron Source for Pseudomonas Aeruginosa during in Vivo Coculture. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Oglesby-Sherrouse, A.G. Interactions between Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Staphylococcus Aureus during Co-Cultivations and Polymicrobial Infections. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 6141–6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machan, Z.A.; Taylor, G.W.; Pitt, T.L.; Cole, P.J.; Wilson, R. 2-Heptyl-4-Hydroxyquinoline N-Oxide, an Antistaphylococcal Agent Produced by Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1992, 30, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, R.; Narh, J.K.; Urlaub, M.; Jankiewicz, O.; Johnson, C.; Livingston, B.; Dahl, J.-U. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Kills Staphylococcus Aureus in a Polyphosphate-Dependent Manner. mSphere 2024, 9, e0068624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Qiao, J.; Yu, W.; Pan, X.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Lu, S.-E. Phenazine-1-Carboxylic Acid Produced by Pseudomonas chlororaphis YL-1 Is Effective against Acidovorax Citrulli. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghergab, A.; Selin, C.; Tanner, J.; Brassinga, A.K.; Dekievit, T. Pseudomonas chlororaphis PA23 Metabolites Protect against Protozoan Grazing by the Predator Acanthamoeba Castellanii. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selin, C.; Habibian, R.; Poritsanos, N.; Athukorala, S.N.P.; Fernando, D.; de Kievit, T.R. Phenazines Are Not Essential for Pseudomonas chlororaphis PA23 Biocontrol of Sclerotinia Sclerotiorum, but Do Play a Role in Biofilm Formation. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2010, 71, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.C.; Richard, W.; Handley, C.; Happold, F.C. The Tryptophanase-Indole Reaction: Some Observations on the Production of Tryptophanase by Esch. coli; in Particular the Effect of the Presence of Glucose and Amino Acids on the Formation of Tryptophanase. Biochem. J. 1941, 35, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanofsky, C.; Horn, V.; Gollnick, P. Physiological Studies of Tryptophan Transport and Tryptophanase Operon Induction in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 6009–6017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Zere, T.R.; Weber, M.M.; Wood, T.K.; Whiteley, M.; Hidalgo-Romano, B.; Valenzuela, E.; McLean, R.J.C. Indole Production Promotes Escherichia coli Mixed-Culture Growth with Pseudomonas Aeruginosa by Inhibiting Quorum Signaling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Jayaraman, A.; Wood, T.K. Indole Is an Inter-Species Biofilm Signal Mediated by SdiA. BMC Microbiol. 2007, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, R.S.; Beyhan, S.; Saini, S.G.; Yildiz, F.H.; Bartlett, D.H. Indole Acts as an Extracellular Cue Regulating Gene Expression in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 3504–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, C.L.; Darkoh, C.; Shimmin, L.; Farhana, N.; Kim, D.-K.; Okhuysen, P.C.; Hixson, J. Fecal Indole as a Biomarker of Susceptibility to Cryptosporidium Infection. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 2299–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laatsch, H.; Thomson, R.H.; Cox, P.J. Spectroscopic Properties of Violacein and Related Compounds: Crystal Structure of Tetramethylviolacein. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1984, 2, 1331–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yada, S.; Wang, Y.; Zou, Y.; Nagasaki, K.; Hosokawa, K.; Osaka, I.; Arakawa, R.; Enomoto, K. Isolation and Characterization of Two Groups of Novel Marine Bacteria Producing Violacein. Mar. Biotechnol. 2008, 10, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.L.; Göcke, Y.; Bolten, C.; Brock, N.L.; Dickschat, J.S.; Wittmann, C. Microbial Production of the Drugs Violacein and Deoxyviolacein: Analytical Development and Strain Comparison. Biotechnol. Lett. 2012, 34, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahul, S.; Chandrashekhar, P.; Hemant, B.; Bipinchandra, S.; Mouray, E.; Grellier, P.; Satish, P. In Vitro Antiparasitic Activity of Microbial Pigments and Their Combination with Phytosynthesized Metal Nanoparticles. Parasitol. Int. 2015, 64, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.Y.; Yoon, K.; Lee, J.I.; Mitchell, R.J. Violacein: Properties and Production of a Versatile Bacterial Pigment. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 465056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz, C.; Webb, J.S.; Schupp, P.J.; Phang, S.Y.; Penesyan, A.; Egan, S.; Steinberg, P.; Kjelleberg, S. Marine Biofilm Bacteria Evade Eukaryotic Predation by Targeted Chemical Defense. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruldass, C.A.; Masalamany, S.R.L.; Venil, C.K.; Ahmad, W.A. Antibacterial Mode of Action of Violacein from Chromobacterium violaceum UTM5 against Staphylococcus Aureus and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 5164–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyakhovchenko, N.S.; Efimova, V.A.; Seliverstov, E.S.; Anis’kov, A.A.; Solyanikova, I.P. Bacteriostatic Activity of Janthinobacterium lividum and Purified Violacein Fraction against Clavibacter Michiganensis. Processes 2024, 12, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanelli, M.; Mandic, M.; Kalakona, M.; Vasilakos, S.; Kekos, D.; Nikodinovic-Runic, J.; Topakas, E. Microbial Production of Violacein and Process Optimization for Dyeing Polyamide Fabrics With Acquired Antimicrobial Properties. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, J.H.; Leal, F.C.; Fukuda, T.T.H.; Alcoforado Diniz, J.; Almeida, F.; Pupo, M.T.; da Silva Neto, J.F. Interplay between Two Quorum Sensing-Regulated Pathways, Violacein Biosynthesis and VacJ/Yrb, Dictates Outer Membrane Vesicle Biogenesis in Chromobacterium violaceum. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 2432–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon, L.L.; Miranda, C.C.; De Souza, A.O.; Durán, N. Antileishmanial Activity of the Violacein Extracted from Chromobacterium violaceum. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001, 48, 449–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, S.C.P.; Blanco, Y.C.; Justo, G.Z.; Nogueira, P.A.; Rodrigues, F.L.S.; Goelnitz, U.; Wunderlich, G.; Facchini, G.; Brocchi, M.; Duran, N.; et al. Violacein Extracted from Chromobacterium violaceum Inhibits Plasmodium Growth in Vitro and in Vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 2149–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodade, V.S.; Aggarwal, S.C.; Eremiev, A.; Bao, E.; Porche, S.; Toscano, J.P. Development of Hydropersulfide Donors to Study Their Chemical Biology. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2022, 36, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washio, J.; Sato, T.; Koseki, T.; Takahashi, N. Hydrogen Sulfide-Producing Bacteria in Tongue Biofilm and Their Relationship with Oral Malodour. J. Med. Microbiol. 2005, 54, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, H.; Odagiri, M.; Ito, T.; Okabe, S. Microbial Community Structures and in Situ Sulfate-Reducing and Sulfur-Oxidizing Activities in Biofilms Developed on Mortar Specimens in a Corroded Sewer System. Water Res. 2009, 43, 4729–4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas-Lopez, D.; Carrilero, L.; Matrat, S.; Montero, N.; Claverol, S.; Filipovic, M.R.; Gonzalez-Zorn, B. H2S Mediates Interbacterial Communication through the Air Reverting Intrinsic Antibiotic Resistance. bioRxiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Salti, T.; Zanditenas, E.; Trebicz-Geffen, M.; Benhar, M.; Ankri, S. Impact of Reactive Sulfur Species on Entamoeba Histolytica: Modulating Viability, Motility, and Biofilm Degradation Capacity. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaValle, B.; Staalsoe, T.; Kurtzhals, J.A.L.; Hempel, C. Investigation of Hydrogen Sulfide Gas as a Treatment against P. falciparum, Murine Cerebral Malaria, and the Importance of Thiolation State in the Development of Cerebral Malaria. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, J.; Eichinger, D. Acetylation of the Entamoeba Histone H4 N-Terminal Domain Is Influenced by Short-Chain Fatty Acids That Enter Trophozoites in a pH-Dependent Manner. Int. J. Parasitol. 2008, 38, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenkaufer, G.M.; Eichinger, D.J.; Singh, U. Trichostatin A Effects on Gene Expression in the Protozoan Parasite Entamoeba Histolytica. BMC Genom. 2007, 8, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, L.; Enea, V.; Eichinger, D. Identification of a Developmentally Regulated Transcript Expressed during Encystation of Entamoeba invadens. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1994, 67, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppi, A.; Eichinger, D. Regulation of Entamoeba invadens Encystation and Gene Expression with Galactose and N-Acetylglucosamine. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1999, 102, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrenkaufer, G.M.; Haque, R.; Hackney, J.A.; Eichinger, D.J.; Singh, U. Identification of Developmentally Regulated Genes in Entamoeba Histolytica: Insights into Mechanisms of Stage Conversion in a Protozoan Parasite. Cell Microbiol. 2007, 9, 1426–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiner, E.K.; Rumbaugh, K.P.; Williams, S.C. Inter-Kingdom Signaling: Deciphering the Language of Acyl Homoserine Lactones. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, A.J.; Whittall, C.; Lazenby, J.J.; Chhabra, S.R.; Pritchard, D.I.; Cooley, M.A. The Immunomodulatory Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Signalling Molecule N-(3-Oxododecanoyl)-L-Homoserine Lactone Enters Mammalian Cells in an Unregulated Fashion. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2007, 85, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Cámara, M. Quorum Sensing and Environmental Adaptation in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: A Tale of Regulatory Networks and Multifunctional Signal Molecules. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2009, 12, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravchenko, V.V.; Kaufmann, G.F.; Mathison, J.C.; Scott, D.A.; Katz, A.Z.; Grauer, D.C.; Lehmann, M.; Meijler, M.M.; Janda, K.D.; Ulevitch, R.J. Modulation of Gene Expression via Disruption of NF-kappaB Signaling by a Bacterial Small Molecule. Science 2008, 321, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hooi, D.; Chhabra, S.R.; Pritchard, D.; Shaw, P.E. Bacterial N-Acylhomoserine Lactone-Induced Apoptosis in Breast Carcinoma Cells Correlated with down-Modulation of STAT3. Oncogene 2004, 23, 4894–4902, Erratum in Oncogene 2004, 23, 9450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, J.M.; Messenger, A.J. Occurrence, Biochemistry and Physiology of Phenazine Pigment Production. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 1986, 27, 211–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzikiewicz, H. Secondary Metabolites from Fluorescent Pseudomonads. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1993, 10, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitahara, M.; Nakamura, H.; Matsuda, Y.; Hamada, M.; Naganawa, H.; Maeda, K.; Umezawa, H.; Iitaka, Y. Saphenamycin, a Novel Antibiotic from a Strain of Streptomyces. J. Antibiot. 1982, 35, 1412–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, J.B.; Nielsen, J. Phenazine Natural Products: Biosynthesis, Synthetic Analogues, and Biological Activity. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 1663–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, Y.; Kitahara, T. Total Synthesis of Phenazinomycin and Its Enantiomer via High-Pressure Reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 4993–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.K. PLUMBING THE OCEAN DEPTHS FOR DRUGS: New Genera of Marine Bacteria May Be the next Big Sources of Natural Products. Chem. Eng. News Arch. 2003, 81, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudilliere, B.; Bernardelli, P.; Berna, P. Chapter 28. To Market, to Market—2000. In Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; Volume 36, pp. 293–318. ISBN 978-0-12-040536-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pierson, L.S.; Pierson, E.A. Metabolism and Function of Phenazines in Bacteria: Impacts on the Behavior of Bacteria in the Environment and Biotechnological Processes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 86, 1659–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñero-Fernandez, S.; Chimerel, C.; Keyser, U.F.; Summers, D.K. Indole Transport across Escherichia coli Membranes. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 1793–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, P.; Widmer, G.; Wang, Y.; Ozaki, L.S.; Alves, J.M.; Serrano, M.G.; Puiu, D.; Manque, P.; Akiyoshi, D.; Mackey, A.J.; et al. The Genome of Cryptosporidium Hominis. Nature 2004, 431, 1107–1112, Erratum in Nature 2004, 432, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlowic, M.C.; Somepalli, M.; Sateriale, A.; Herbert, G.T.; Gibson, A.R.; Cuny, G.D.; Hedstrom, L.; Striepen, B. Genetic Ablation of Purine Salvage in Cryptosporidium Parvum Reveals Nucleotide Uptake from the Host Cell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 21160–21165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funkhouser-Jones, L.J.; Xu, R.; Wilke, G.; Fu, Y.; Schriefer, L.A.; Makimaa, H.; Rodgers, R.; Kennedy, E.A.; VanDussen, K.L.; Stappenbeck, T.S.; et al. Microbiota-Produced Indole Metabolites Disrupt Mitochondrial Function and Inhibit Cryptosporidium Parvum Growth. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.Y.; Lim, S.; Cho, G.; Kwon, J.; Mun, W.; Im, H.; Mitchell, R.J. Chromobacterium violaceum Delivers Violacein, a Hydrophobic Antibiotic, to Other Microbes in Membrane Vesicles. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, P.; Mierzejewska, J.; Skrzeszewska, P.; Witkowska, A.; Oksejuk, K.; Sitkiewicz, E.; Krawczyk, M.; Świadek, M.; Głuchowska, A.; Marlicka, K.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles of Janthinobacterium lividum as Violacein Carriers in Melanoma Cell Treatment. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, P.; Kumar, R.; Tatu, U. Chaperoning a Cellular Upheaval in Malaria: Heat Shock Proteins in Plasmodium Falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2007, 153, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavella, T.A.; da Silva, N.S.M.; Spillman, N.; Kayano, A.C.A.V.; Cassiano, G.C.; Vasconcelos, A.A.; Camargo, A.P.; da Silva, D.C.B.; Fontinha, D.; Salazar Alvarez, L.C.; et al. Violacein-Induced Chaperone System Collapse Underlies Multistage Antiplasmodial Activity. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cauz, A.C.G.; Carretero, G.P.B.; Saraiva, G.K.V.; Park, P.; Mortara, L.; Cuccovia, I.M.; Brocchi, M.; Gueiros-Filho, F.J. Violacein Targets the Cytoplasmic Membrane of Bacteria. ACS Infect. Dis. 2019, 5, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, P.S.; Maria, S.S.; Vidal, B.C.; Haun, M.; Durán, N. Violacein Cytotoxicity and Induction of Apoptosis in V79 Cells. Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 2000, 36, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, J.D.; Grubb, D.R.; Lawen, A. The Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (Deltapsi(m)) in Apoptosis; an Update. Apoptosis 2003, 8, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, A.M.d.S.; de Queiroz, J.D.F.; de Medeiros, S.R.B.; Lima, T.K.d.S.; Agnez-Lima, L.F. Violacein Induces Cell Death by Triggering Mitochondrial Membrane Hyperpolarization in Vitro. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, C.V.; Bos, C.L.; Versteeg, H.H.; Justo, G.Z.; Durán, N.; Peppelenbosch, M.P. Molecular Mechanism of Violacein-Mediated Human Leukemia Cell Death. Blood 2004, 104, 1459–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birg, A.; Lin, H.C. The Role of Bacteria-Derived Hydrogen Sulfide in Multiple Axes of Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumètre, A.; Aubert, D.; Puech, P.-H.; Hohweyer, J.; Azas, N.; Villena, I. Interaction Forces Drive the Environmental Transmission of Pathogenic Protozoa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.; Bouchez, T.; Nicolas, V.; Robert, S.; Loret, J.F.; Lévi, Y. Amoebae in Domestic Water Systems: Resistance to Disinfection Treatments and Implication in Legionella Persistence. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 97, 950–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Zaragoza, S. Ecology of Free-Living Amoebae. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 1994, 20, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanditenas, E.; Trebicz-Geffen, M.; Kolli, D.; Domínguez-García, L.; Farhi, E.; Linde, L.; Romero, D.; Chapman, M.; Kolodkin-Gal, I.; Ankri, S. Digestive Exophagy of Biofilms by Intestinal Amoeba and Its Impact on Stress Tolerance and Cytotoxicity. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbach, M.A.; Sonnenburg, J.L. Eating For Two: How Metabolism Establishes Interspecies Interactions in the Gut. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 10, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donia, M.S.; Fischbach, M.A. Small Molecules from the Human Microbiota. Science 2015, 349, 1254766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachier, F.; Andriamihaja, M.; Larraufie, P.; Ahn, E.; Lan, A.; Kim, E. Production of Hydrogen Sulfide by the Intestinal Microbiota and Epithelial Cells and Consequences for the Colonic and Rectal Mucosa. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2021, 320, G125–G135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, M.; Mentel, M.; van Hellemond, J.J.; Henze, K.; Woehle, C.; Gould, S.B.; Yu, R.-Y.; van der Giezen, M.; Tielens, A.G.M.; Martin, W.F. Biochemistry and Evolution of Anaerobic Energy Metabolism in Eukaryotes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012, 76, 444–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeelani, G.; Nozaki, T. Entamoeba Thiol-Based Redox Metabolism: A Potential Target for Drug Development. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2016, 206, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albenberg, L.; Esipova, T.V.; Judge, C.P.; Bittinger, K.; Chen, J.; Laughlin, A.; Grunberg, S.; Baldassano, R.N.; Lewis, J.D.; Li, H.; et al. Correlation Between Intraluminal Oxygen Gradient and Radial Partitioning of Intestinal Microbiota. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 1055–1063.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walocha, R.; Kim, M.; Wong-Ng, J.; Gobaa, S.; Sauvonnet, N. Organoids and Organ-on-Chip Technology for Investigating Host-Microorganism Interactions. Microbes Infect. 2024, 26, 105319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, S.L.; Petri, W.A. The Intestinal Bacterial Microbiome and E. Histolytica Infection. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2016, 3, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biofilm Compound | Examples | Function in Biofilm | Effect on Bacteria | Effect on Protozoa | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCFAs | Acetate, Propionate, Butyrate | Support community structure | Toxic to some; energy source for others | Modulate Entamoeba encystation; inhibit Cryptosporidium, Toxoplasma | [65,66,67,68,69,70] |

| AHLs | C8-HSL, 3-oxo-C12-HSL, C4-HSL | Regulate biofilm formation, stress, antimicrobials | Mediate cooperation and competition | Affect protozoan behavior; toxic to grazers | [71,122] |

| Phenazines | PCA, Pyocyanin | Maintain redox balance | Disrupt membranes; induce ROSs | Kill protozoa; stress-induced toxicity | [80,87,88,89] |

| Indole | - | Interkingdom signaling | Induce stress; limit growth | Disrupt physiology; reduces mitosomal potential | [90,93,135] |

| Violacein | - | Defense; interspecies signaling | Damage membranes; cause ATP leakage | Cause swelling, lysis; inhibit ATPase | [37,101,139,140] |

| RSSs | H2S, Cys-SSH | Modulate bacterial interactions | Sensitize to antibiotics | Inhibit protein synthesis, motility, and virulence | [111,112,113] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mahapatra, S.; Ankri, S. The Role of Biofilm-Derived Compounds in Microbial and Protozoan Interactions. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010064

Mahapatra S, Ankri S. The Role of Biofilm-Derived Compounds in Microbial and Protozoan Interactions. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010064

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahapatra, Smruti, and Serge Ankri. 2026. "The Role of Biofilm-Derived Compounds in Microbial and Protozoan Interactions" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010064

APA StyleMahapatra, S., & Ankri, S. (2026). The Role of Biofilm-Derived Compounds in Microbial and Protozoan Interactions. Microorganisms, 14(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010064