Effects of Silage Inoculants on the Quality and Microbial Community of Whole-Plant Corn Silage Under Different Fertilization Treatments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Determination of Indicators

2.3. 16S rDNA Sequencing

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pre-Ensiling Chemical Composition of Fresh Whole-Plant Corn

3.2. Effect of Silage Inoculant on the Quality of Whole-Plant Corn Silage Under Different Fertilization Treatments (30 Days)

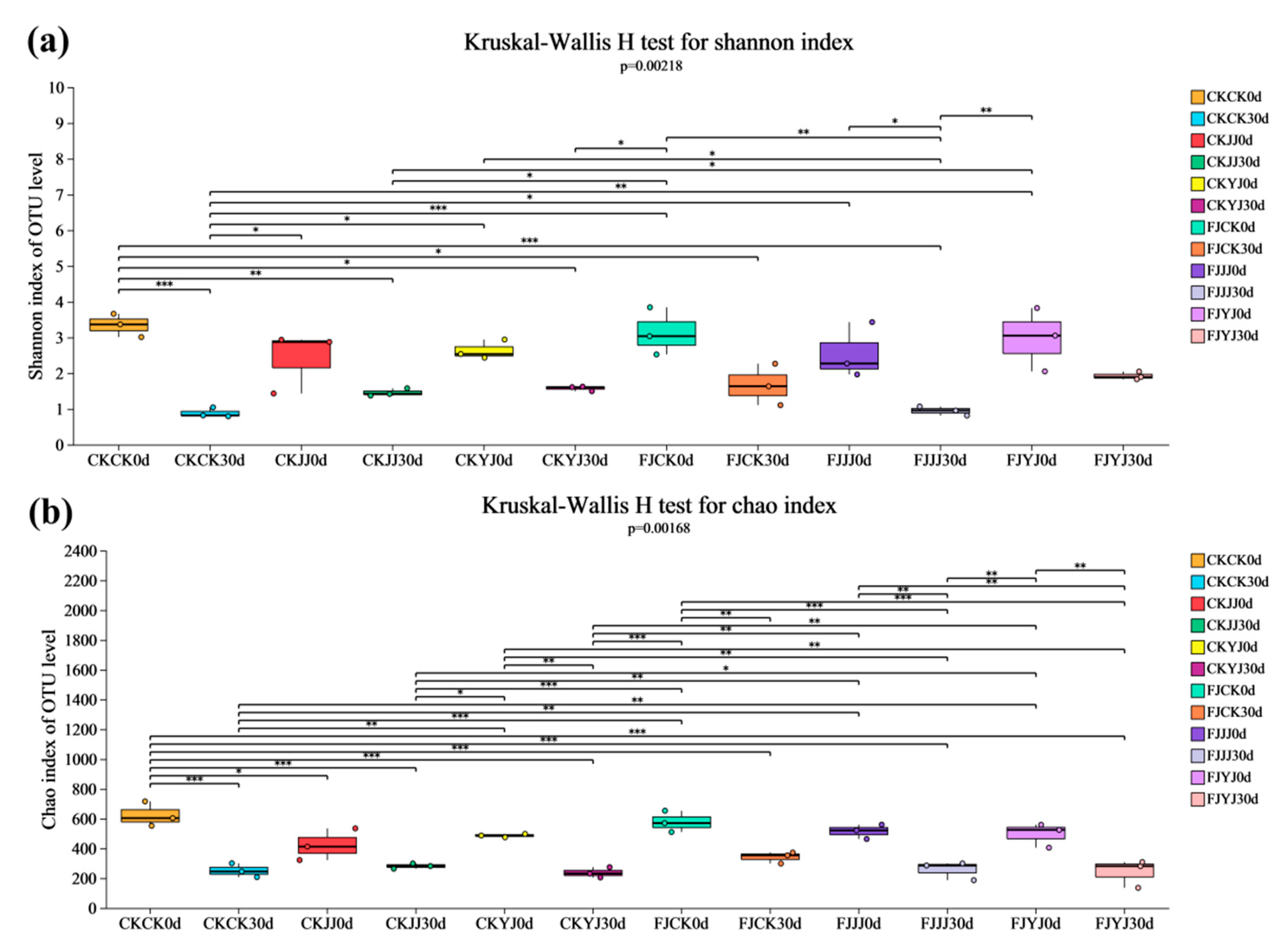

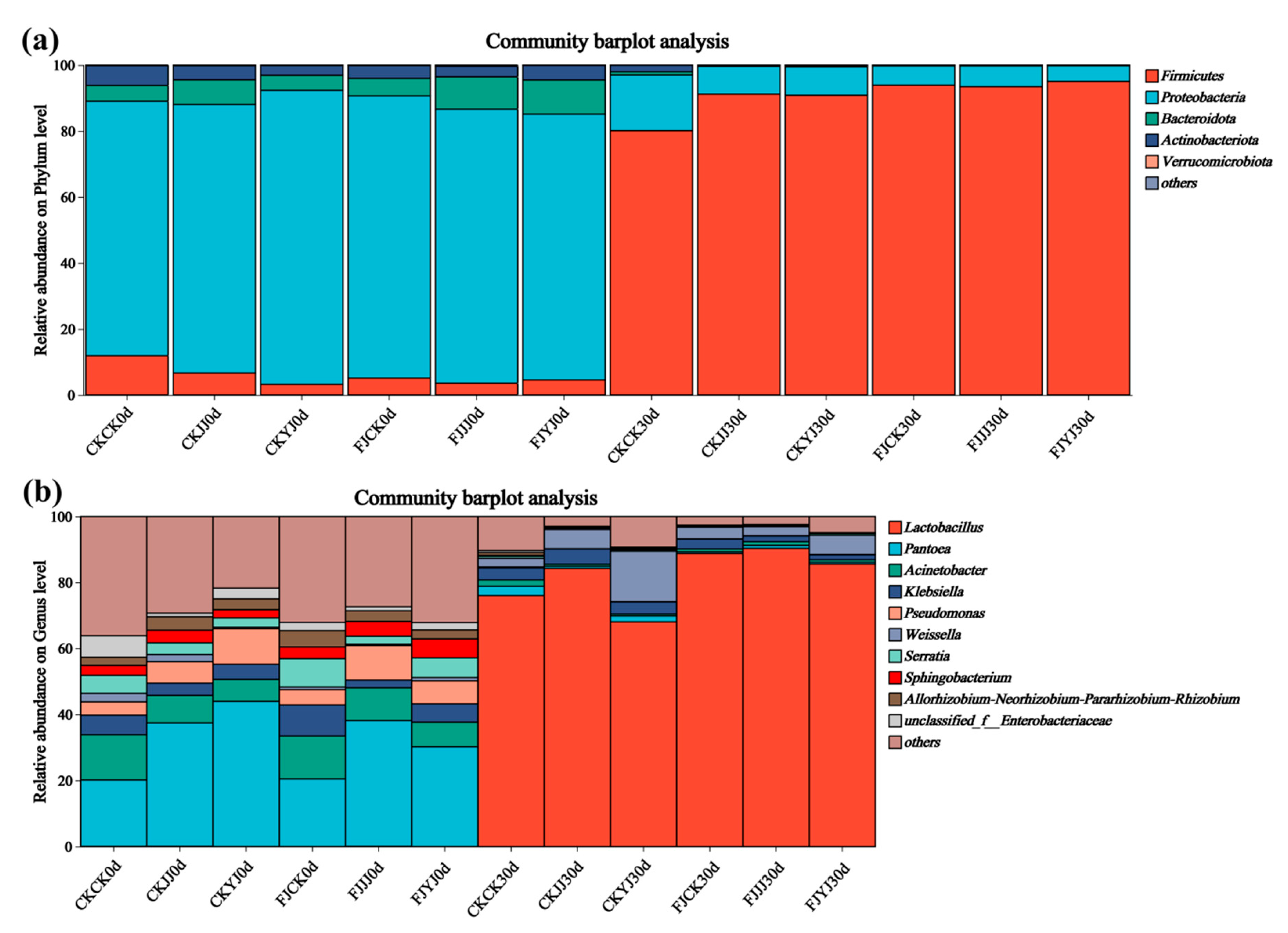

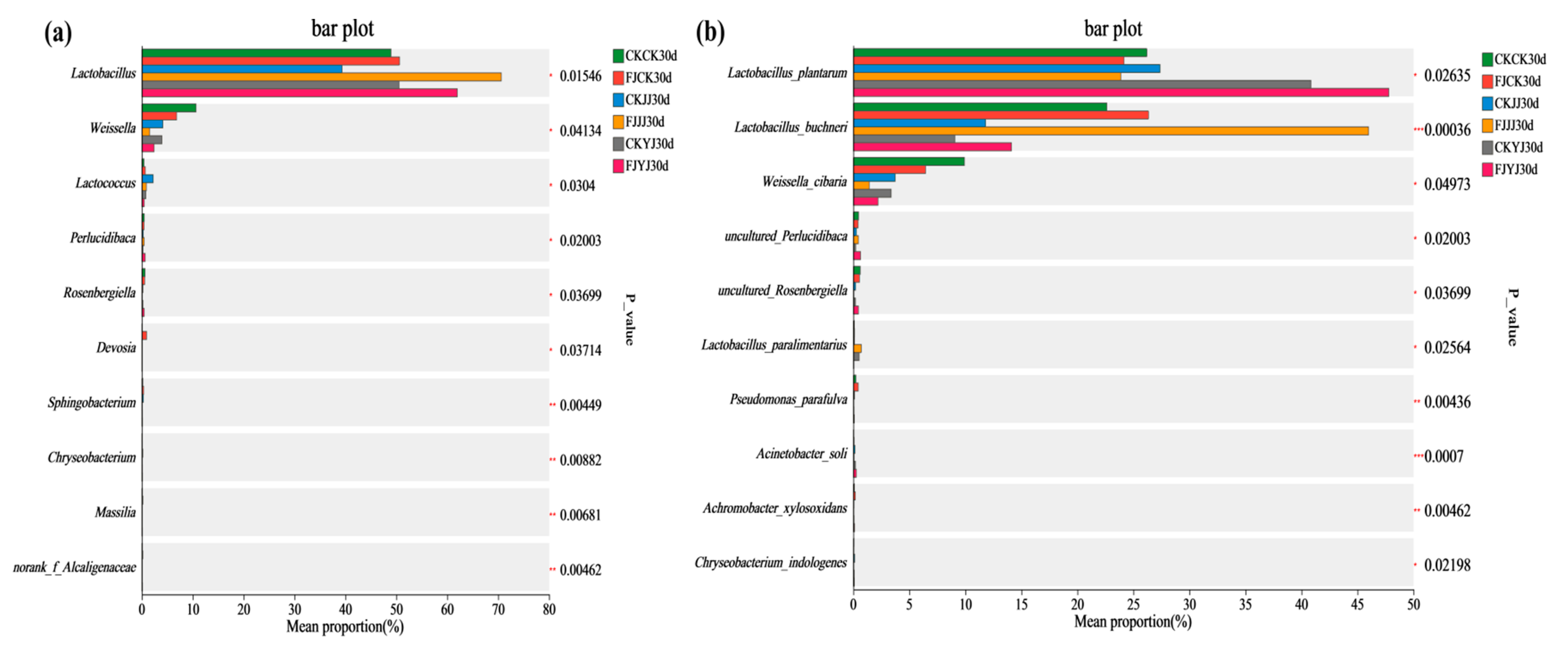

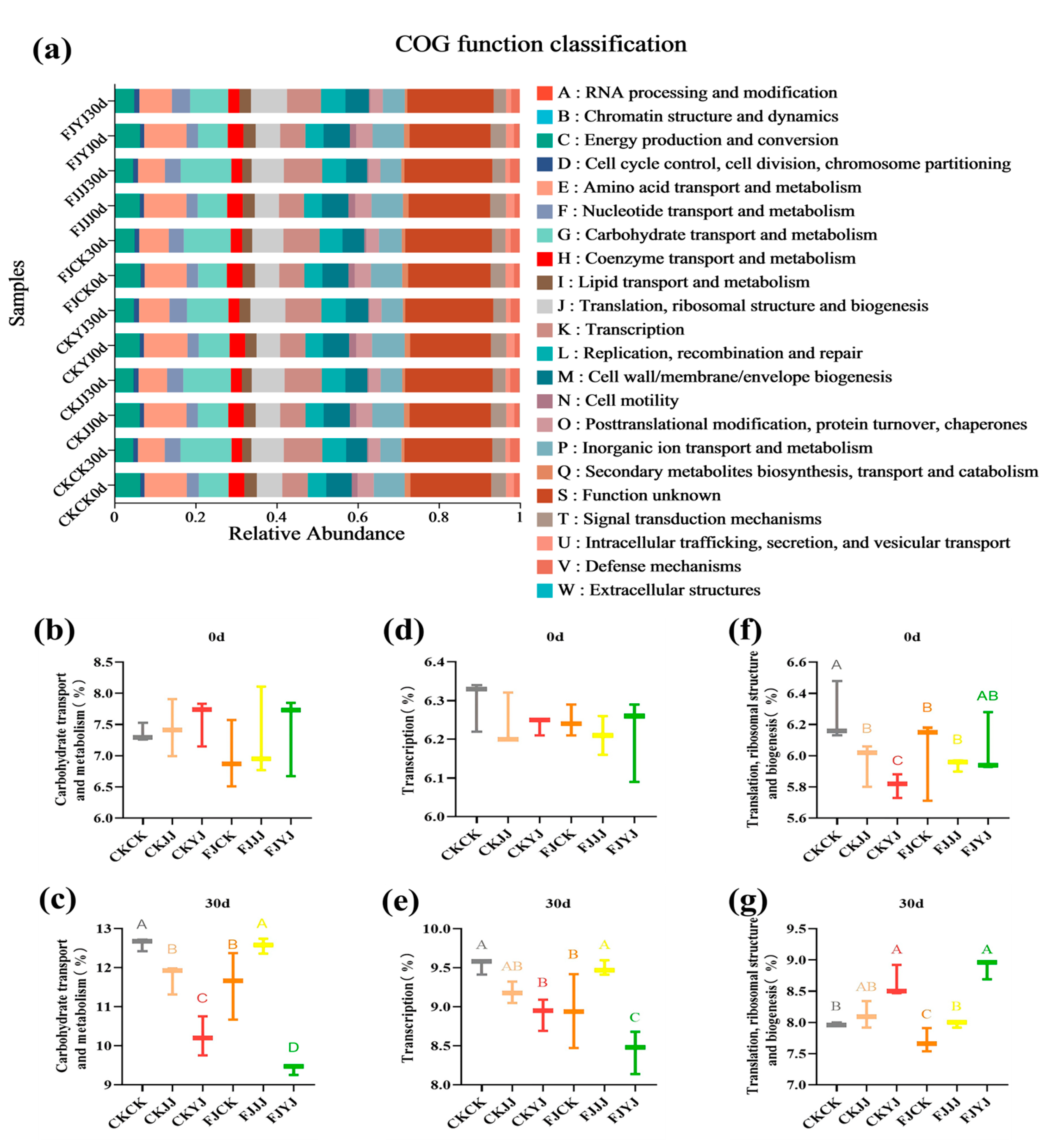

3.3. Analysis of Microbial Diversity in Whole-Plant Corn Silage Treated with Silage Inoculant Under Different Fertilization Regimes

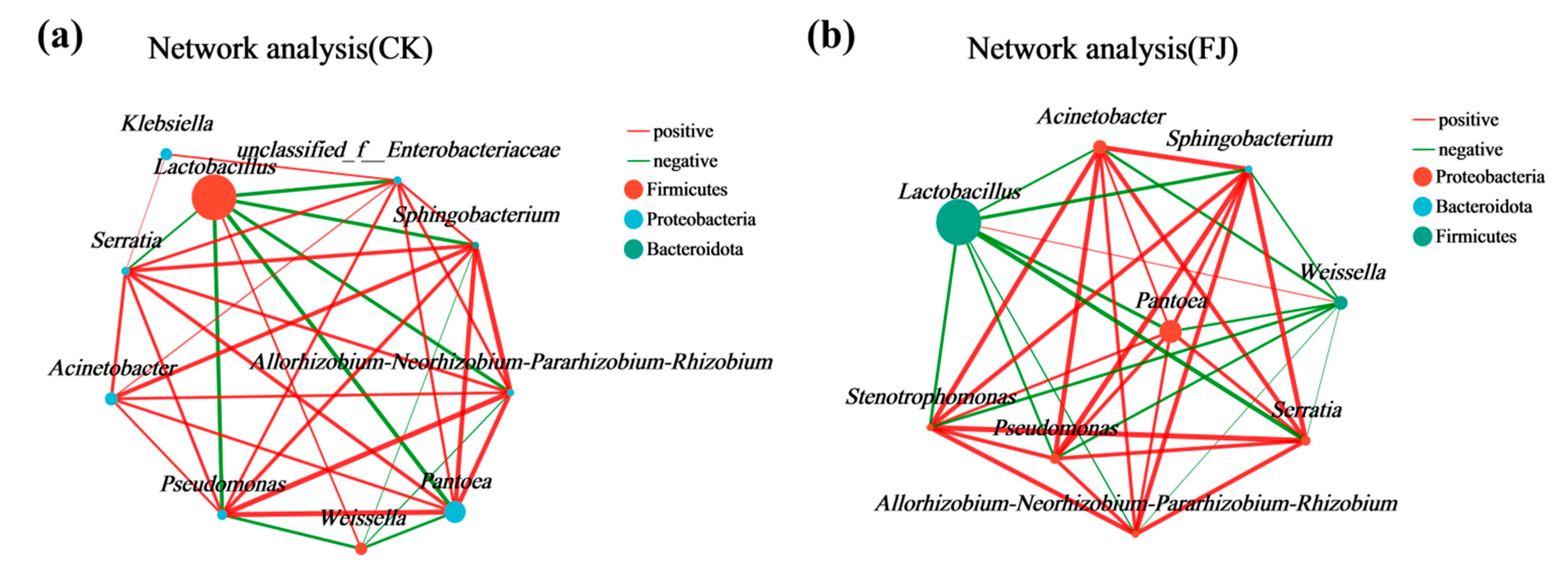

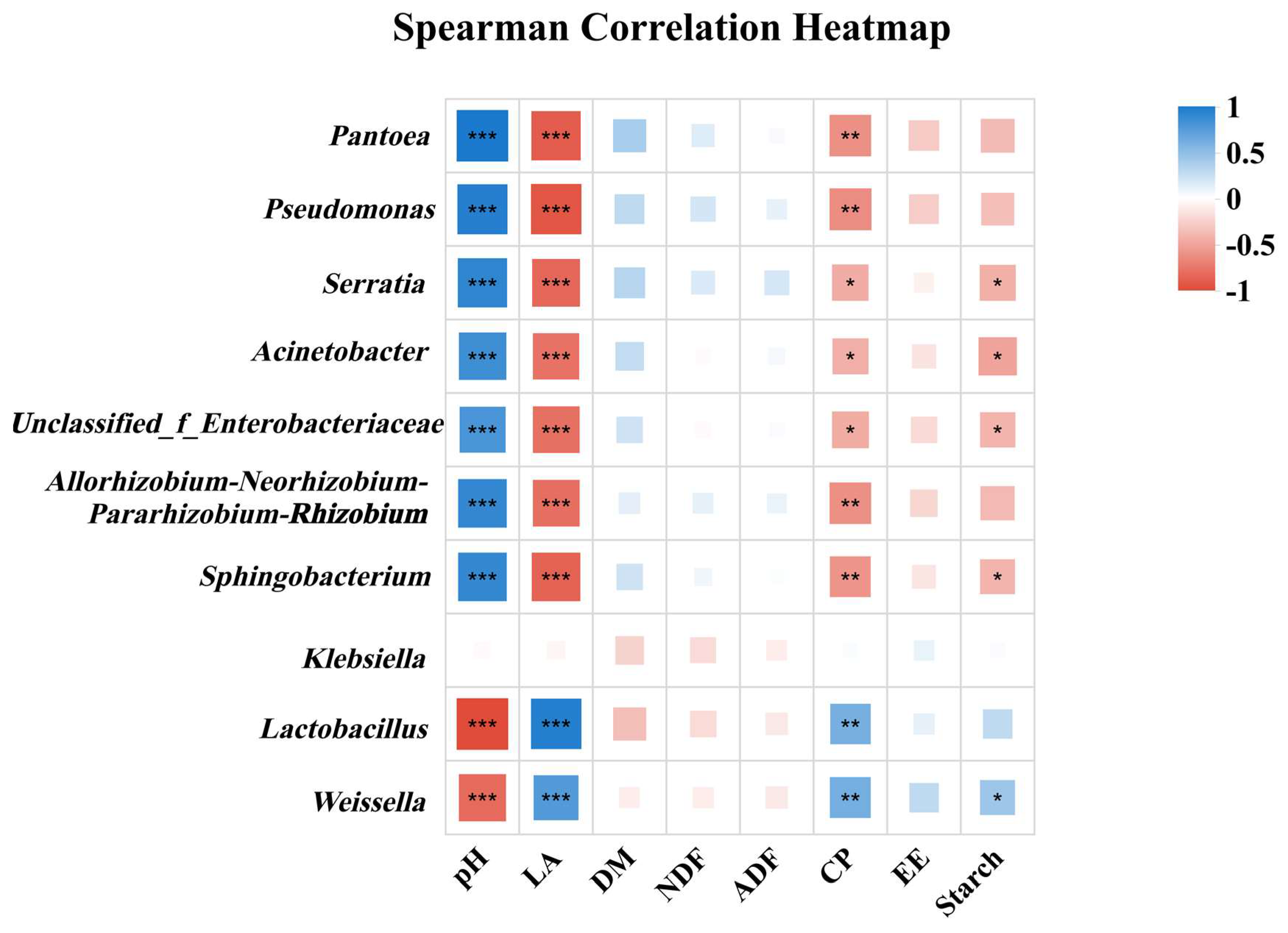

3.4. Correlation Between Dominant Bacterial Communities and Key Nutritional Indicators in Whole-Plant Corn Silage Treated with Silage Inoculant Under Different Fertilization Regimes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, Z.; Han, C.; Shi, Z.; Li, J.; Luo, E. Rebuilding the crop-livestock integration system in China—Based on the perspective of circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 393, 136347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnatam, K.S.; Mythri, B.; Un Nisa, W.; Sharma, H.; Meena, T.K.; Rana, P.; Vikal, Y.; Gowda, M.; Dhillon, B.S.; Sandhu, S. Silage maize as a potent candidate for sustainable animal husbandry development—Perspectives and strategies for genetic enhancement. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1150132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liang, X.; Zhang, Y. Advancements in the Research and Application of Whole-Plant Maize Silage for Feeding Purposes. Animals 2025, 15, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srour, A.Y.; Ammar, H.A.; Subedi, A.; Pimentel, M.; Cook, R.L.; Bond, J.; Fakhoury, A.M. Microbial Communities Associated with Long-Term Tillage and Fertility Treatments in a Corn-Soybean Cropping System. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, N.; Jiang, C.; Wang, Y. Effects of irrigation type and fertilizer application rate on growth, yield, and water and fertilizer use efficiency of silage corn in the North China Plain. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.-P.; Xue, Z.-Q.; Yang, Z.-Y.; Chai, Z.; Niu, J.-P.; Shi, Z.-Y. Effects of microbial organic fertilizers on Astragalus membranaceus growth and rhizosphere microbial community. Ann. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; He, X.; Liu, Q.; Gao, F.; Zeng, C.; Li, D. Bio-Organic Fertilizer Modulates the Rhizosphere Microbiome to Enhance Sugarcane Growth and Suppress Smut Disease. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuc, L.V.; Minh, V.Q. Improvement of Glutinous Corn and Watermelon Yield by Lime and Microbial Organic Fertilizers. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2022, 2022, 2611529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, C.O.; Wang, Y.; Gao, L.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, J.; Jiang, J. The performance of lactic acid bacteria in silage production: A review of modern biotechnology for silage improvement. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundharrajan, I.; Park, H.S.; Rengasamy, S.; Sivanesan, R.; Choi, K.C. Application and Future Prospective of Lactic Acid Bacteria as Natural Additives for Silage Production—A Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hao, J.; Zhao, M.; Yan, X.; Jia, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ge, G. Effects of different temperature and density on quality and microbial population of wilted alfalfa silage. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber, T.; Fliegerová, K.; Terler, G.; Resch, R.; Zebeli, Q.; Hartinger, T. Mixed ensiling of drought-impaired grass with agro-industrial by-products and silage additives improves the nutritive value and shapes the microbial community of silages. Grass Forage Sci. 2024, 79, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Okoye, C.O.; Gao, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, J. Fermentation profile and bioactive component retention in honeysuckle residue silages inoculated with lactic acid bacteria: A promising feed additive for sustainable agriculture. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 224, 120315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Bao, J.; Luo, Y.; Yu, Z. Additives affect the distribution of metabolic profile, microbial communities and antibiotic resistance genes in high-moisture sweet corn kernel silage. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 315, 123821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Cai, X.; Shao, T.; Yangzong, Z.; Wang, W.; Ma, P.; Li, J.; Zhao, J.; Gallo, A.; Yuan, X. Effects of bacterial inoculants on the microbial community, mycotoxin contamination, and aerobic stability of corn silage infected in the field by toxigenic fungi. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2022, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Yamasaki, S.; Oya, T.; Cai, Y. Cellulase–lactic acid bacteria synergy action regulates silage fermentation of woody plant. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2023, 16, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wu, N.; Na, N.; Ding, H.; Sun, L.; Fang, Y.; Li, D.; Li, E.; Yang, B.; Wei, X.; et al. Dynamics of fermentation quality, bacterial communities, and fermentation weight loss during fermentation of sweet sorghum silage. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yin, X.-J.; Li, J.-F.; Wang, S.-R.; Dong, Z.-H.; Shao, T. Effects of developmental stage and store time on the microbial community and fermentation quality of sweet sorghum silage. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 21, 1543–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Ran, Q.; Li, H.; Zhang, X. Succession of Microbial Communities of Corn Silage Inoculated with Heterofermentative Lactic Acid Bacteria from Ensiling to Aerobic Exposure. Fermentation 2021, 7, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; You, M.; Du, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zuo, C.; Zhao, M.; Wang, H.; Yan, X.; Chen, C. Effects of N Fertilization During Cultivation and Lactobacillus plantarum Inoculation at Ensiling on Chemical Composition and Bacterial Community of Mulberry Silage. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 735767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Li, Y.; Yang, F.; Cui, W.; Huang, X.; Dong, D.; Dong, L.; Zhang, B. Optimizing the Production of High-Quality Silage from Jingkenuo 2000 Fresh Waxy Maize: The Synergistic Effects of Microbial Fertilizer and Fermentation Agents. Fermentation 2025, 11, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, P. Activated carbon from lignocellulosics precursors: A review of the synthesis methods, characterization techniques and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 1393–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.Q.; Ju, Z.L.; Chai, J.K.; Jiao, T.; Jia, Z.F.; Casper, D.P.; Zeng, L.; Wu, J.P. Effects of silage additives and varieties on fermentation quality, aerobic stability, and nutritive value of oat silage. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 3151–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawu, O.; Ravhuhali, K.E.; Mokoboki, H.K.; Lebopa, C.K.; Sipango, N. Sustainable Use of Legume Residues: Effect on Nutritive Value and Ensiling Characteristics of Maize Straw Silage. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Li, Z.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X. Interactive effect of inoculant and dried jujube powder on the fermentation quality and nitrogen fraction of alfalfa silage. Anim. Sci. J. 2016, 88, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soe Htet, M.N.; Hai, J.-B.; Bo, P.T.; Gong, X.-W.; Liu, C.-J.; Dang, K.; Tian, L.-X.; Soomro, R.N.; Aung, K.L.; Feng, B.-L. Evaluation of Nutritive Values through Comparison of Forage Yield and Silage Quality of Mono-Cropped and Intercropped Maize-Soybean Harvested at Two Maturity Stages. Agriculture 2021, 11, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, C.B.; dos Santos, R.M.; de Souza Buzo, F.; de Andrade da Silva, M.S.R.; Rigobelo, E.C. Effects of Chemical Fertilization and Microbial Inoculum on Bacillus subtilis Colonization in Soybean and Maize Plants. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 901157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, L.; Shaver, R.D.; Grant, R.J.; Schmidt, R.J. Silage review: Interpretation of chemical, microbial, and organoleptic components of silages. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4020–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.E.d.S.; Jalal, A.; Aguilar, J.V.; de Camargos, L.S.; Zoz, T.; Ghaley, B.B.; Abdel-Maksoud, M.A.; Alarjani, K.M.; AbdElgawad, H.; Teixeira Filho, M.C.M. Yield, nutrition, and leaf gas exchange of lettuce plants in a hydroponic system in response to Bacillus subtilis inoculation. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1248044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Khan, N.A.; Zhou, X.; Tang, S.; Zhou, C.; Tan, Z.; Liu, Y. Bacterial inoculants and enzymes based silage cocktails boost the ensiling quality of biomasses from reed, corn and rice straw. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2024, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlahig, S.; Neji, M.; Atoui, A.; Seddik, M.; Dbara, M.; Yahia, H.; Nagaz, K.; Najari, S.; Khorchani, T.; Loumerem, M. Genetic and seasonal variation in forage quality of lucerne (Medicago sativa L.) for resilience to climate change in arid environments. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 100986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Yuan, B.; Li, F.; Du, J.; Yu, M.; Tang, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, P. Fermentation Characteristics, Nutrient Content, and Microbial Population of Silphium perfoliatum L. Silage Produced with Different Lactic Acid Bacteria Additives. Animals 2025, 15, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Xu, G.; Ni, K.; Yang, F. Effect of lactic acid bacteria and wheat bran on the fermentation quality and bacterial community of Broussonetia papyrifera silage. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, Y.; Lei, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, J.; He, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; et al. Enhancing alfalfa and sorghum silage quality using agricultural wastes: Fermentation dynamics, microbial communities, and functional insights. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 728, Correction in BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Xue, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Te, R.; Wu, X.; Na, N.; Wu, N.; Qili, M.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, Y. Community Synergy of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Cleaner Fermentation of Oat Silage Prepared with a Multispecies Microbial Inoculant. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e00705–e00723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, J.; Dong, Z.; Dong, D.; Shao, T. Fermentation profile and microbial diversity of temperate grass silage inoculated with epiphytic microbiota from tropical grasses. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 6007–6019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; You, S.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Ge, G.; Jia, Y. Evaluating the fermentation characteristics, bacterial community, and predicted functional profiles of native grass ensiled with different additives. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1025536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Zhang, L.; Xin, Y.; Xu, Z.; He, H.; Kong, J. Oxygen-Inducible Conversion of Lactate to Acetate in Heterofermentative Lactobacillus brevis ATCC 367. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e01659-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Cai, B.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, X.; Yang, J.; Ma, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, F. Bacterial community structure and metabolites after ensiling paper mulberry mixed with corn or wheat straw. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1356705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Wang, N.; Rinne, M.; Ke, W.; Weinberg, Z.G.; Da, M.; Bai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Guo, X. The bacterial community and metabolome dynamics and their interactions modulate fermentation process of whole crop corn silage prepared with or without inoculants. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021, 14, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.F.; Wenqiong, C.; Umar, M.; Changfa, W. Biochemical properties of lactic acid bacteria for efficient silage production: An update. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1581430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Du, S.; Sun, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Sun, P.; Bai, B.; Ge, G.; Jia, Y.; Wang, Z. Volatile metabolomics and metagenomics reveal the effects of lactic acid bacteria on alfalfa silage quality, microbial communities, and volatile organic compounds. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, H.; Guo, Q.; Sudu, B.; Han, H. Modulation of the microbial community and the fermentation characteristics of wrapped natural grass silage inoculated with composite bacteria. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2025, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Xie, L.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Feng, L.; Li, Y.; Lei, Y.; Sun, Y. Effect of Lactiplantibacillus and sea buckthorn pomace on the fermentation quality and microbial community of paper mulberry silage. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1412759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Hong, Q.; Yang, B.; Wang, J. Lactic acid bacteria strains selected from fermented total mixed rations improve ensiling and in vitro rumen fermentation characteristics of corn stover silage. Anim. Biosci. 2022, 35, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Huang, B.; Lin, J.; Yang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Liu, D.; Sun, B. Isolation and screening of high biofilm producing lactic acid bacteria, and exploration of its effects on the microbial hazard in corn straw silage. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 136009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ensilage Experimental Design Combinations | |

|---|---|

| CKCK | natural fermentation + conventional fertilization |

| CKJJ | natural fermentation + liquid microbial inoculant + conventional fertilization |

| CKYJ | natural fermentation + microbial organic fertilizer + conventional fertilization |

| FJCK | silage inoculants + conventional fertilization |

| FJJJ | silage inoculants + liquid microbial inoculant + conventional fertilization |

| FJYJ | silage inoculants + microbial organic fertilizer + conventional fertilization |

| Item | Treatment | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | JJ | YJ | ||

| DM% | 28.00 ± 0.05 | 30.00 ± 0.03 | 31.00 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Starch% | 27.95 ± 0.08 | 28.94 ± 0.10 | 29.09 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

| CP% | 7.80 ± 0.01 | 7.14 ± 0.06 | 7.76 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| EE% | 5.83 ± 0.01 | 5.81 ± 0.02 | 5.21 ± 0.02 | <0.001 |

| NDF% | 33.24 ± 0.0 | 39.39 ± 0.86 | 44.38 ± 0.06 | <0.001 |

| ADF% | 16.02 ± 0.15 | 18.17 ± 0.04 | 22.18 ± 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Item | CK (Natural Fermentation) | FJ (Silage Inoculants) | p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | JJ | YJ | CK | JJ | YJ | A | T | A × T | |

| DM% | 29.68 ± 1.02 | 26.43 ± 1.21 | 33.54 ± 0.14 | 28.54 ± 0.81 | 27.58 ± 0.71 | 31.55 ± 0.88 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| pH% | 3.72 ± 0.01 | 3.62 ± 0.04 | 3.80 ± 0.03 | 3.76 ± 0.02 | 3.61 ± 0.01 | 3.67 ± 0.01 | 0.091 | <0.001 | 0.032 |

| LA% | 7.90 ± 0.02 | 7.63 ± 0.03 | 7.82 ± 0.02 | 7.94 ± 0.07 | 7.97 ± 0.03 | 7.94 ± 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.009 |

| Starch% | 28.00 ± 0.16 | 29.54 ± 0.13 | 29.87 ± 0.13 | 30.53 ± 0.35 | 31.01 ± 0.05 | 33.26 ± 0.04 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| CP% | 8.48 ± 0.04 | 7.63 ± 0.04 | 8.11 ± 0.02 | 8.42 ± 0.02 | 8.76 ± 0.01 | 9.03 ± 0.03 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| EE% | 6.60 ± 0.03 | 6.12 ± 0.04 | 6.69 ± 0.02 | 7.37 ± 0.06 | 8.87 ± 0.10 | 7.96 ± 0.02 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| NDF% | 37.31 ± 0.03 | 36.10 ± 0.49 | 40.06 ± 0.10 | 31.65 ± 0.08 | 31.62 ± 0.76 | 33.47 ± 0.09 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ADF% | 21.36 ± 0.03 | 20.92 ± 0.16 | 20.25 ± 0.08 | 18.60 ± 0.10 | 15.21 ± 0.13 | 15.71 ± 0.04 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dong, D.; Ainizirehong, G.; Aihemaiti, M.; Huang, X.; Li, Y.; Yao, H.; Yan, Y.; Hou, M.; Cui, W. Effects of Silage Inoculants on the Quality and Microbial Community of Whole-Plant Corn Silage Under Different Fertilization Treatments. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010065

Dong D, Ainizirehong G, Aihemaiti M, Huang X, Li Y, Yao H, Yan Y, Hou M, Cui W. Effects of Silage Inoculants on the Quality and Microbial Community of Whole-Plant Corn Silage Under Different Fertilization Treatments. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010065

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Deli, Gulinigeer Ainizirehong, Maierhaba Aihemaiti, Xin Huang, Yang Li, Huaibing Yao, Yuanyuan Yan, Min Hou, and Weidong Cui. 2026. "Effects of Silage Inoculants on the Quality and Microbial Community of Whole-Plant Corn Silage Under Different Fertilization Treatments" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010065

APA StyleDong, D., Ainizirehong, G., Aihemaiti, M., Huang, X., Li, Y., Yao, H., Yan, Y., Hou, M., & Cui, W. (2026). Effects of Silage Inoculants on the Quality and Microbial Community of Whole-Plant Corn Silage Under Different Fertilization Treatments. Microorganisms, 14(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010065